Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens. A Potential Health Risk in Water Mist Systems Used as a Cooling Intervention

Abstract

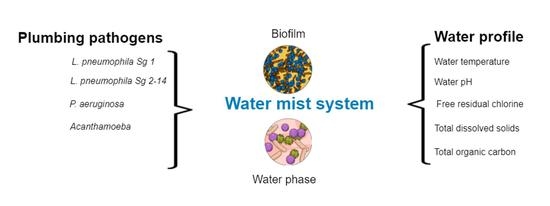

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Occurrence of Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens in Water Mist Systems

2.2. The Concentration of Detected OPPPs

2.3. The Frequency and Distribution of OPPPs Differed by Sample Type and Water Source

2.4. Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogen Occurrence by Water Source

2.5. Seasonal Occurrence of Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens

2.6. Water Temperature

2.7. Water pH

2.8. Total Dissolved Solids (TDS)

2.9. Free Chlorine Residual

2.10. Total Organic Carbon (TOC)

2.11. The Relationship between Water Profile Parameters

2.12. Relationship between Water Profile Parameters and the Occurrence of OPPPs in Water Mist Systems

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bioaerosol Sampling

Bioaerosol Sample Processing

4.2. Biofilm Samples

Biofilm Swab Sample Preparation

4.3. Water Samples

Water Sample Preparation and Analysis

4.4. Analytical Methods

4.4.1. Detection and Measurement of Legionella pneumophila Species

4.4.2. Detection and Measurement of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

4.4.3. Detection and Measurement of Acanthamoeba and Naegleria fowleri

4.4.4. Detection and Measurement of Mycobacteria avium

4.5. Data and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demirjian, A.; Lucas, C.E.; Garrison, L.E.; Kozak-Muiznieks, N.A.; States, S.; Brown, E.W.; Wortham, J.M.; Beaudoin, A.; Casey, M.L.; Marriott, C.; et al. The importance of clinical surveillance in detecting Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks: A large outbreak in a hospital with a Legionella disinfection system—Pennsylvania, 2011–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanamori, H.; Weber, D.J.; Rutala, W.A. Healthcare outbreaks associated with a water reservoir and infection prevention strategies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henningson, E.W.; Ahlberg, M.S. Evaluation of microbiological aerosol samplers: A review. J. Aerosol. Sci. 1994, 25, 1459–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkinham, J.O., III; Pruden, A.; Edwards, M.A. Opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens: Increasingly important pathogens in drinking water. Pathogens 2015, 4, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bauer, M.; Mathieu, L.; Deloge-Abarkan, M.; Remen, T.; Tossa, P.; Hartemann, P.; Zmirou-Navier, D. Legionella bacteria in shower aerosols increase the risk of pontiac fever among older people in retirement homes. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2008, 62, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.M.; Thomas, T.; Stuetz, R.M.; Ashbolt, N.J. Your Garden Hose: A Potential Health Risk Due to Legionella spp. Growth Facilitated by Free-Living Amoebae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 10456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassier, P.; Landelle, C.; Reyrolle, M.; Nicolle, M.C.; Slimani, S.; Etienne, J.; Vanhems, P.; Jarraud, S. Hospital washbasin water: Risk of Legionella-contaminated aerosol inhalation. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 85, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borella, P.; Montagna, M.T.; Stampi, S.; Stancanelli, G.; Romano-Spica, V.; Triassi, M.; Marchesi, I.; Bargellini, A.; Tatò, D.; Napoli, C.; et al. Legionella contamination in hot water of Italian hotels. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5805–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leoni, E.; Sanna, T.; Zanetti, F.; Dallolio, L. Controlling Legionella and Pseudomonas aeruginosa re-growth in therapeutic spas: Implementation of physical disinfection treatments, including UV/ultrafiltration, in a respiratory hydrotherapy system. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bennett, E.; Ashton, M.; Calvert, N.; Chaloner, J.; Cheesbrough, J.; Egan, J.; Farrell, I.; Hall, I.; Harrison, T.G.; Naik, F.C.; et al. Barrow-in-Furness: A large community legionellosis outbreak in the UK. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 1763–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Julien, R.; Dreelin, E.; Whelton, A.J.; Lee, J.; Aw, T.G.; Dean, K.; Mitchell, J. Knowledge gaps and risks associated with premise plumbing drinking water quality. AWWA Water Sci. 2020, 2, e1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkinham, J.O. Common Features of Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4533–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbolt, N.J. Environmental (Saprozoic) Pathogens of Engineered Water Systems: Understanding Their Ecology for Risk Assessment and Management. Pathogens 2015, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Edwards, M.A.; Falkinham, J.O.; Pruden, A. Probiotic Approach to Pathogen Control in Premise Plumbing Systems? A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruden, A.; Edwards, M.; Falkinham, J., III. State of the science and research needs for opportunistic pathogens in premise plumbing. Water Res. Found. 2013, 183, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann, D.L.; American Public Health A. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual: An Official Report of the American Public Health Association, 20th ed.; an imprint of the American Public Health Association; APHA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham, J.O.; Hilborn, E.D.; Arduino, M.J.; Pruden, A.; Edwards, M.A. Epidemiology and ecology of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens: Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium avium, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haupt, T.E.; Heffernan, R.T.; Kazmierczak, J.J.; Nehls-Lowe, H.; Rheineck, B.; Powell, C.; Leonhardt, K.K.; Chitnis, A.S.; Davis, J.P. An Outbreak of Legionnaires Disease Associated with a Decorative Water Wall Fountain in a Hospital. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2012, 33, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Gouveia, C.L.M.; Soares, P.M.M.; Cardoso, R.M.; Mendes, M.T.; Trigo, R.M. The unprecedented 2014 Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Portugal: Atmospheric driving mechanisms. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkinham, J.O. Nontuberculous mycobacteria from household plumbing of patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkinham, J.O.; Iseman, M.D.; de Haas, P.; van Soolingen, D. Mycobacterium avium in a shower linked to pulmonary disease. J. Water Health 2008, 6, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bédard, E.; Laferrière, C.; Charron, D.; Lalancette, C.; Renaud, C.; Desmarais, N.; Déziel, É.; Prévost, M. Post-outbreak investigation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa faucet contamination by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and environmental factors affecting positivity. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, H.; Geginat, G.; Hogardt, M.; Kramer, A.; Dürken, M.; Schroten, H.; Tenenbaum, T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreak in a pediatric oncology care unit caused by an errant water jet into contaminated siphons. Pediatric Infect. Dis. J. 2012, 31, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, P.J.; Lazensky, B.; Van Zile, K.W.; Elliott, K.E.; Dooyema, C.A.; Visvesvara, G.S.; Beach, M.J.; Yoder, J.S. Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis in Florida A Case Report and Epidemiological Review of Florida Cases. J. Environ. Health 2013, 75, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parsonson, F.; Nicholls, C. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in North Queensland–The diagnostic challenges of Naegleria fowleri. Pathology 2016, 48, S105–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, E.E.; Méabed, E.M.H.; Abdallah, I.; Wahed, W.Y.A. Acanthamoeba keratitis in noncompliant soft contact lenses users: Genotyping and risk factors, a study from Cairo, Egypt. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudmeyer, R. Climate in the Pilbara. In Agriculture and Food; Department of Agriculture and Food: Perth, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Meteorology. Average Annual and Monthly Maximum, Minimum and Mean Temperatures Canberra: Australian Government. 2016; [Updated January 2021; Cited 2019 March 25, 2021]. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/climate_averages/temperature/index.jsp (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Liu, L.; Xing, X.; Hu, C.; Wang, H. One-year survey of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens and free-living amoebae in the tap-water of one northern city of China. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 77, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Edwards, M.; Falkinham, J.O.; Pruden, A. Molecular survey of the occurrence of Legionella spp., Mycobacterium spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and amoeba hosts in two chloraminated drinking water distribution systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6285–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barna, Z.; Kádár, M.; Kálmán, E.; Szax, A.S.; Vargha, M. Prevalence of Legionella in premise plumbing in Hungary. Water Res. 2016, 90, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, A.; Mimi, Z. The Hospital Tap Water System as a Source of Nosocomial Infections for Staff Members and Patients in West Bank Hospitals. Environ. Forensics 2008, 9, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.J.; O’Connell, K.; Vesper, S.J.; Mistry, J.H.; King, D.; Kostich, M.; Pfaller, S. Widespread molecular detection of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 in cold water taps across the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 3145–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Giron, M.J.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Luo, C.; Elk, M.; Ryu, H.; Hoelle, J.; Domingo, J.W.S.; Konstantinidis, K.T. Biofilms on Hospital Shower Hoses: Characterization and Implications for Nosocomial Infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2872–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Mendis, N.; Trigui, H.; Oliver, J.D.; Faucher, S.P. The importance of the viable but non-culturable state in human bacterial pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dwidjosiswojo, Z.; Richard, J.; Moritz, M.M.; Dopp, E.; Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. Influence of copper ions on the viability and cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa under conditions relevant to drinking water environments. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Bae, S. Biofilms in premise plumbing systems as a double-edged sword: Microbial community composition and functional profiling of biofilms in a tropical region. J. Water Health 2020, 18, 172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Shen, Y.; Smith, R.L.; Dong, S.; Nguyen, T.H. Effect of disinfectant residuals on infection risks from Legionella pneumophila released by biofilms grown under simulated premise plumbing conditions. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuy, M.; Mazoua, S.; Berne, F.; Bodet, C.; Garrec, N.; Herbelin, P.; Ménard-Szczebara, F.; Oberti, S.; Rodier, M.-H.; Soreau, S.; et al. Efficiency of water disinfectants against Legionella pneumophila and Acanthamoeba. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K.; Mitchell, J. Reverse QMRA for Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Premise Plumbing to Inform Risk Management. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 04019120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, E.; Prévost, M.; Déziel, E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in premise plumbing of large buildings. Microbiologyopen 2016, 5, 937–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, I.; Fletcher, L.; Beggs, C.; Denton, M.; Conway, S.; Peckham, D. An aerobiological model of aerosol survival of different strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from people with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2010, 9, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allegra, S.; Leclerc, L.; Massard, P.A.; Girardot, F.; Riffard, S.; Pourchez, J. Characterization of aerosols containing Legionella generated upon nebulization. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, J.E.; Carnie, J.A.; Tallis, G.F.; Zwolak, B.; Hart, W.G.; Guest, C.S.; Ryan, N.J.; Leydon, J.; Tan, A.G.; Gordon, I.R. An outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease at the Melbourne Aquarium, April 2000: Investigation and case–control studies. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 180, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.S.; Graham, F.F.; Harte, D.J.G.; Baker, M.G.; Ambrose, C.D.; Humphrey, A.R.G. Epidemiological investigation of a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Christchurch, New Zealand: The value of spatial methods for practical public health. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013, 141, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsiaflaka, A.; Pournaras, S.; Kristo, I.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Kyritsi, M.; Velonakis, E.; Vatopoulos, A.C.; Hadjichristodoulo, C. Epidemiological investigation of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 2 to 14 isolates from water samples by amplified fragment length polymorphism and sequence-based typing and detection of virulence traits. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6102–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilvington, S.; Gray, T.; Dart, J.; Morlet, N.; Beeching, J.R.; Frazer, D.G.; Matheson, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis: The role of domestic tap water contamination in the United Kingdom. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ku, J.; Chan, F.; Beckingsale, P. Acanthamoeba keratitis cluster: An increase in Acanthamoeba keratitis in Australia. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 37, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.; McDonnell, G.; Denyer, S.P.; Maillard, J.-Y. Free-living amoebae and their intracellular pathogenic microorganisms: Risks for water quality. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waso, M.; Dobrowsky, P.H.; Hamilton, K.A.; Puzon, G.; Miller, H.; Khan, W.; Ahmed, W. Abundance of Naegleria fowleri in roof-harvested rainwater tank samples from two continents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 5700–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, M.J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Oliverio, A.M.; Webster, T.M.; Nichols, L.M.; Honda, J.R.; Chan, E.D.; Adjemian, J.; Dunn, R.R.; Fierer, N. Ecological analyses of mycobacteria in showerhead biofilms and their relevance to human health. mBio 2018, 9, e01614-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, M.J.; Halstrom, S.; Wylie, J.T.; Walsh, T.; Kaksonen, A.H.; Sutton, D.; Braun, K.; Puzon, G.J. Characterization of a drinking water distribution pipeline terminally colonized by Naegleria fowleri. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2890–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, Y.; Bouchon, D.; Héchard, Y.; Moulin, L. Spatio-temporal survey of opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens in the Paris drinking water distribution system. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baveja, C.P.; Prabhav, A. Statistical analysis of microbiological diagnostic tests. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 35, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. Critical Factors Controlling Regrowth of Opportunistic Pathogens in Premise Plumbing; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Western Australia Department of Water. Newman Water Reserve Drinking Water Source Protection Plan; Government of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2009; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Darwin University. Source Water Key to Bacterial Water Safety in Remote Northern Australia; NewsRx Health & Science: Brisbane, Australia, 2019; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J.; Dowsett, A.; Dennis, P.; Lee, J.; Keevil, C. Influence of plumbing materials on biofilm formation and growth of Legionella pneumophila in potable water systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adabanija, M.A.; Afolabi, O.A.; Lawal, L. The influence of bedrocks on groundwater chemistry in a crystalline basement complex of southwestern Nigeria. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, H.Y.; Ji, P.; Gomez-Alvarez, V.; Pruden, A.; Edwards, M.A.; Ashbolt, N.J. Effect of temperature and colonization of Legionella pneumophila and Vermamoeba vermiformis on bacterial community composition of copper drinking water biofilms. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, A.; Kato, N.; Sakamoto, R.; Kimura, S.; Yamaguchi, K. Temperature-Dependent Parasitic Relationship between Legionella pneumophila and a Free-Living Amoeba (Acanthamoeba castellanii). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4585–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agudelo-Vera, C.; Avvedimento, S.; Boxall, J.; Creaco, E.; De Kater, H.; Di Nardo, A.; Djukic, A.; Douterelo, I.; Fish, K.E.; Rey, P.L.I.; et al. Drinking Water Temperature around the Globe: Understanding, Policies, Challenges and Opportunities. Water 2020, 12, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, J.; Buse, H.; Struewing, I.; Zhao, A.; Lytle, D.; Ashbolt, N. Annual variations and effects of temperature on Legionella spp. and other potential opportunistic pathogens in a bathroom. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 2326–2336.63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Masters, S.; Hong, Y.; Stallings, J.; Falkinham, J.O.; Edwards, M.A.; Pruden, A. Effect of Disinfectant, Water Age, and Pipe Material on Occurrence and Persistence of Legionella, mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Two Amoebas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchesi, I.; Cencetti, S.; Marchegiano, P.; Frezza, G.; Borella, P.; Bargellini, A. Control of Legionella contamination in a hospital water distribution system by monochloramine. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2012, 40, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals, O.; Serrano-Suárez, A.; Salvadó, H.; Méndez, J.; Cervero-Aragó, S.L.; de Porras, V.R.; Dellundé, J.; Araujo, R. Effect of chlorine and temperature on free-living protozoa in operational man-made water systems (cooling towers and hot sanitary water systems) in Catalonia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 6610–6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.; Elfland, C.; Edwards, M. Impact of advanced water conservation features and new copper pipe on rapid chloramine decay and microbial regrowth. Water Res. 2012, 46, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenschlager, K.; Boon, N.; Wang, Y.; Egli, T.; Hammes, F. Overnight stagnation of drinking water in household taps induces microbial growth and changes in community composition. Water Res. 2010, 44, 4868–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogoa, E.; Bodet, C.; Morel, F.; Rodier, M.-H.; Legube, B.; Héchard, Y. Cellular Response of the Amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii to Chlorine, Chlorine Dioxide, and Monochloramine Treatments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 4974–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Proctor, C.R.; Dai, D.; Edwards, M.A.; Pruden, A. Interactive effects of temperature, organic carbon, and pipe material on microbiota composition and Legionella pneumophila in hot water plumbing systems. Microbiome 2017, 5, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health and Safety Executive. Legionnaire’s disease Technical Guidance HSG 274 Part 2. In The Control of Legionella in Hot and Cold-Water Systems; Health and Safety Executive: Merseyside, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute. ANSI/ASHRE Standard 188—2018. In Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems; American National Standards Institute: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- enHealth. Guidelines for Legionella Control in the Operation and Maintenance of Water Distribution Systems in Health and Aged Care Facilities; Australian Government: Canberra, Australian, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, K.K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Yadana, S.; Hansen-Estruch, C.; Lindsley, W.G.; Gray, G.C. Bioaerosol sampling for respiratory viruses in Singapore’s mass rapid transit network. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sampling Procedure and Potential Sampling Sites. In Protocol for Collecting Environmental Samples for Legionella Culture during a Cluster or Outbreak Investigation or When Cases of Disease May Be Associated with a Facility; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Standards Australia. Water Quality—Sampling for microbiological analysis AS 2031–2012: ISO19458-2006; Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Codony, F.; Pérez, L.M.; Adrados, B.; Agustí, G.; Fittipaldi, M.; Morató, J. Amoeba-related health risk in drinking water systems: Could monitoring of amoebae be a complementary approach to current quality control strategies? Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standards Australia and New Zealand. Water Microbiology. Method 1, General Information, and Procedures (ISO 8199:2005, MOD); Standards Australia and New Zealand: Sydney, Australia; Wellington, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Standards Australia. AS5132:2017 Waters-Examination for Legionella spp. including Legionella pneumophila—Using Concentration; Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, S.; Jorgensen, F.; Willis, C.C.C.; Walker, J. Real-time PCR to supplement gold-standard culture-based detection of Legionella in environmental samples. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 1158–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards Australia and New Zealand. AS/NZS 4276.13.2008 Method 13: Pseudomonas aeruginosa—Membrane Filtration Method; Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Cerniglia, C.E. Detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from clinical and environmental samples by amplification of the exotoxin a gene using PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pélandakis, M.; Serre, S.; Pernin, P. Analysis of the 5.8 S rRNA gene and the internal transcribed spacers in Naegleria spp. and in N. fowleri. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2000, 47, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzon, G.J.; Lancaster, J.A.; Wylie, J.T.; Plumb, J.J. Rapid Detection of Naegleria Fowleri in Water Distribution Pipeline Biofilms and Drinking Water Samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6691–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, J.M.; Booton, G.C.; Hay, J.; Niszl, I.A.; Seal, D.V.; Markus, M.B.; Fuerst, P.A.; Byers, T.J. Use of subgenic 18S ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing for genus and genotype identification of Acanthamoebae from humans with keratitis and from sewage sludge. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uppal, M.; McLellan, S.; Collins, M.; Lambrecht, R. A multiplex PCR assay that discriminates Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis from closely related Mycobacteria using primers which detect specific insertion sequences, abstr. Z-58. In Abstracts of the 102nd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel, D.R. Statistics for Censored Environmental Data Using Minitab and R; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

| Opportunistic Pathogen Detected | OPPP Concentration Level | OPPP Concentration Range by Sample Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOFILM (CFU/mL) | Water (CFU/mL | Bioaerosol qPCR * | ||

| L. pneumophila (Sg 1) | Lowest | 1000 | 100 | Not detected |

| Highest | 3000 | 100 | Not detected | |

| L. pneumophila (Sg 2–14) | Lowest | 100 | 10 | Not detected |

| Highest | 1000 | 300 | Not detected | |

| P. aeruginosa | Lowest | 10 | 3 | Detected |

| Highest | 2000 | 350 | Detected | |

| Spearman Rho (ρ) Correlation between Water Profile Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Profile Parameter | Statistical Test and Sample Size | Free Chlorine Residual | Water Temperature | Water pH | Total Dissolved Solids | Total Organic Carbon |

| Free chlorine residual | Spearman rho ρ | 1 | −0.185 | −0.065 | −0.566 | −0.523 |

| Significance (2 tailed) | . | 0.328 | 0.735 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Water temperature | Spearman ρ Correlation | −0.185 | 1 | 0.111 | −0.089 | −0.198 |

| Significance (2 tailed) | 0.328 | . | 0.558 | 0.639 | 0.293 | |

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Water pH | Spearman ρ Correlation | −0.065 | 0.111 | 1 | 0.068 | 0.279 |

| Significance (2 tailed) | 0.735 | 0.558 | . | 0.720 | 0.136 | |

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Total dissolved solids | Spearman ρ Correlation | −0.566 | −0.089 | 0.068 | 1 | 0.549 |

| Significance (2 tailed) | 0.001 | 0.639 | 0.720 | . | 0.002 | |

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Total organic carbon | Spearman ρ Correlation | −0.523 | −0.198 | 0.279 | 0.549 | 1 |

| Significance (2 tailed) | 0.003 | 0.293 | 0.136 | 0.002 | . | |

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Spearman Rho Correlation Analysis between OPPPs and Residual Chlorine, Water Temperature, pH, Total Dissolved Solids, and Total Organic Carbon | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opportunistic Pathogen Detected | Residual Chlorine (mg/L) | Water Temperature (°C) | Water pH (pH Units) | Total Dissolved Solids (mg/L) | Total Organic Carbon (mg/L) |

| L. pneumophila (1) | −0.327 (p = 0.011) | 0.080 (p = 0.543) | 0.074 (p = 0.038) | 0.268 (p = 0.038) | 0.392 (p = 0.002) |

| L. pneumophila (2–14) | −0.401 (p = 0.002) | 0.098 (p = 0.456) | 0.002 (p = 0.987) | 0.418 (p = 0.001) | 0.393 (p = 0.002) |

| P. aeruginosa | −0.423 (p = 0.001) | 0.313 (p = 0.015) | 0.123 (p = 0.348) | 0.480 (p = 0.000) | 0.242 (p = 0.062) |

| Acanthamoeba | 0.067 (p = 0.611) | 0.035 (p = 0.789) | −0.062 (p = 0.637) | −0.057 (p = 0.663) | 0.022 (p = 0.868) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Masaka, E.; Reed, S.; Davidson, M.; Oosthuizen, J. Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens. A Potential Health Risk in Water Mist Systems Used as a Cooling Intervention. Pathogens 2021, 10, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10040462

Masaka E, Reed S, Davidson M, Oosthuizen J. Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens. A Potential Health Risk in Water Mist Systems Used as a Cooling Intervention. Pathogens. 2021; 10(4):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10040462

Chicago/Turabian StyleMasaka, Edmore, Sue Reed, Maggie Davidson, and Jacques Oosthuizen. 2021. "Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens. A Potential Health Risk in Water Mist Systems Used as a Cooling Intervention" Pathogens 10, no. 4: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10040462

APA StyleMasaka, E., Reed, S., Davidson, M., & Oosthuizen, J. (2021). Opportunistic Premise Plumbing Pathogens. A Potential Health Risk in Water Mist Systems Used as a Cooling Intervention. Pathogens, 10(4), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10040462