Making a Comeback: Syphilitic Hepatitis in a Patient with Late Latent Syphilis—Case Report and Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

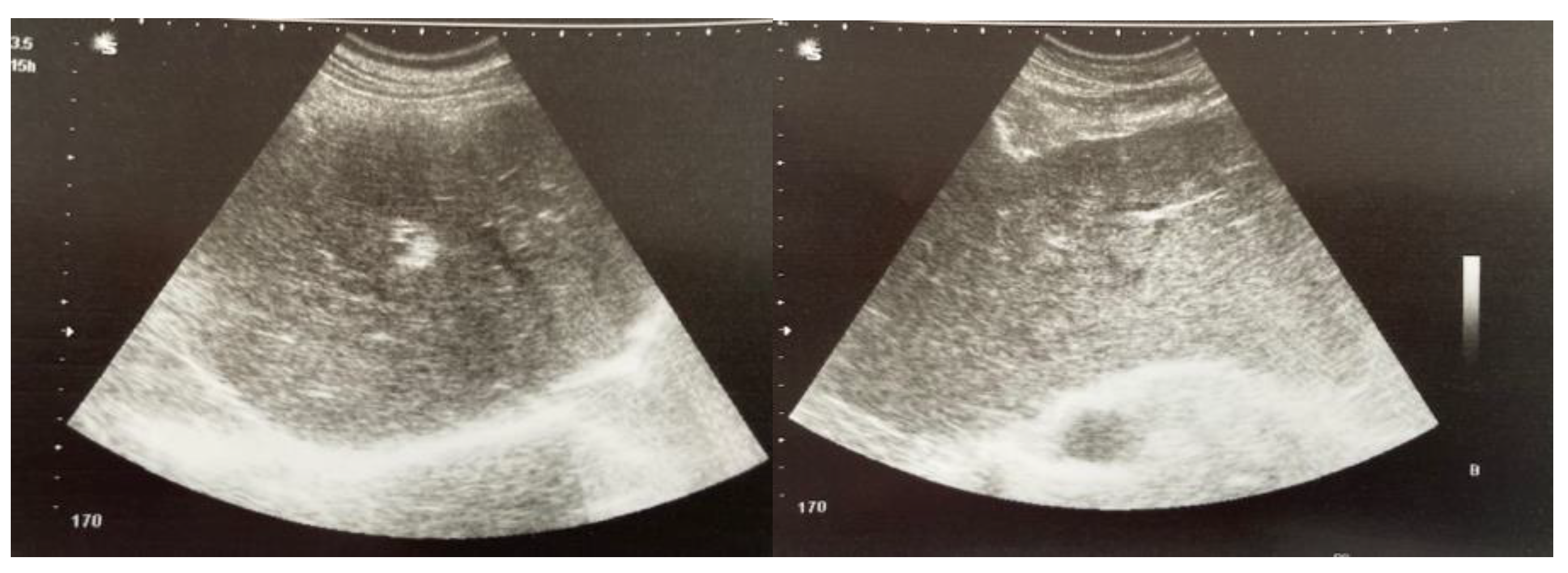

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, N.; Igbinedion, S.O.; Diaz, R.; Alexander, J.S.; Boktor, M.; Knowles, K. Liver Cholestasis Secondary to Syphilis in an Immunocompetent Patient. Case Rep. Hepatol. 2018, 2018, 8645068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandache, C.; Coca, C.; Caro-Sampara, F.; Haberstezer, F.; Coumaros, D.; Blicklé, F.; Andrès, E. A forgotten aetiology of acute hepatitis in immunocompetent patient: Syphilitic infection. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 259, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Hujoel, I.A.; Smyrk, T.C.; Poterucha, J.J. Emerging secondary syphilis presenting as syphilitic hepatitis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 2113–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Lin, S.; Wan, B.; Zhu, Y. A Systematic Literature Review of Syphilitic Hepatitis in Adults. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rowley, J.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Korenromp, E.; Low, N.; Unemo, M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chico, R.M.; Smolak, A.; Newman, L.; Gottlieb, S.; et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: Global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, K.G.; Ram, S.; Rice, P.A. The Modern Epidemic of Syphilis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, M.; Brine, P. An atypical presentation of a re-emerging disease. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2017, 7, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tiecco, G.; Degli Antoni, M.; Storti, S.; Marchese, V.; Focà, E.; Torti, C.; Castelli, F.; Quiros-Roldan, E. A 2021 Update on Syphilis: Taking Stock from Pathogenesis to Vaccines. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.; Lingiah, V.; Niazi, M.; Olivo-Salcedo, R.; Pyrsopoulos, N.; Galan, M.; Shahidullah, A. Acute Liver Injury as a Manifestation of Secondary Syphilis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2021, 8, e00668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemam, A.; Ata, S.; Shaikh, D.; Leuzzi, B.; Makker, J. Syphilitic Hepatitis: A Rare Cause of Acute Liver Injury. Cureus 2021, 13, e14800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullick, C.J.; Liappis, A.P.; Benator, D.A.; Roberts, A.D.; Parenti, D.M.; Simon, G.L. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, e100–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Subedi, A.; Hoilat, G.; Kumar, V.C.S.; Bhutta, A.; Subedi, A.S.; Gupta, A. Syphilitic hepatitis as a manifestation of secondary syphilis. In Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 696–697. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Lin, S.; Wang, M.; Wan, B.; Zhu, Y. Syphilitic hepatitis: A case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.G.; Leal, M.S.; Meireles, D.; Cavadas, S. Syphilitic hepatitis; a rare manifestation of a common disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2021, 14, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marcos, P.; Eliseu, L.; Henrique, M.; Vasconcelos, H. Syphilitic hepatitis: Case report of an overlooked condition. Clin. Case Rep. 2019, 8, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luo, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, Y. Laboratory Diagnostic Tools for Syphilis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 574806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, M.E.; Okeke, N.L.; Hicks, C.B. Treatment of syphilis: A systematic review. JAMA 2014, 312, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018; Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019; pp. 24–31. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/Syphilis.htm (accessed on 1 September 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plesa, A.; Gheorghe, L.; Hincu, C.E.; Clim, A.; Nemteanu, R. Making a Comeback: Syphilitic Hepatitis in a Patient with Late Latent Syphilis—Case Report and Review of the Literature. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11101151

Plesa A, Gheorghe L, Hincu CE, Clim A, Nemteanu R. Making a Comeback: Syphilitic Hepatitis in a Patient with Late Latent Syphilis—Case Report and Review of the Literature. Pathogens. 2022; 11(10):1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11101151

Chicago/Turabian StylePlesa, Alina, Liliana Gheorghe, Corina Elena Hincu, Andreea Clim, and Roxana Nemteanu. 2022. "Making a Comeback: Syphilitic Hepatitis in a Patient with Late Latent Syphilis—Case Report and Review of the Literature" Pathogens 11, no. 10: 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11101151