Chest Imaging for Pulmonary TB—An Update

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Overview of Imaging Techniques Available

3. Imaging Findings in Relation to TB Disease

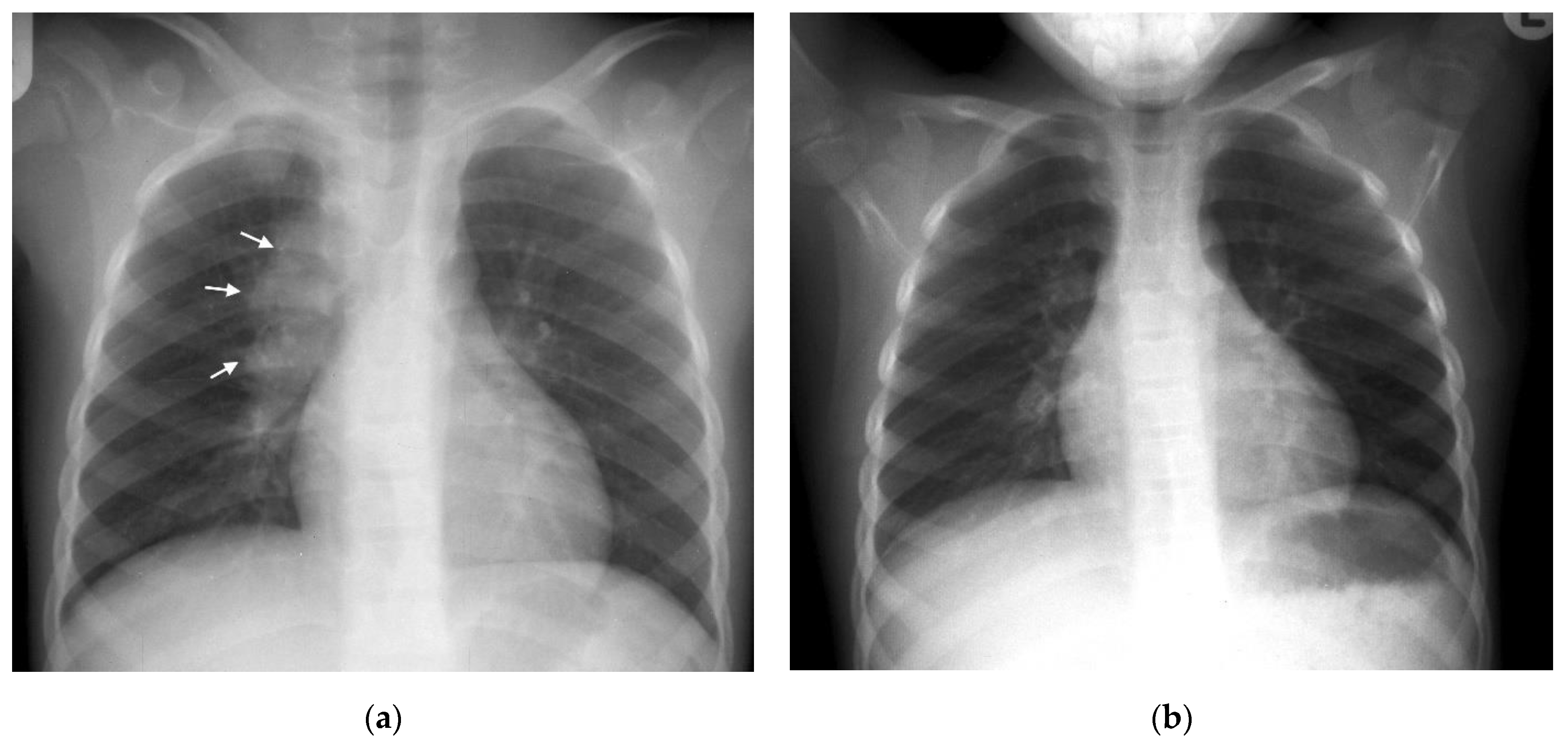

Primary TB

4. Primary Progressive TB

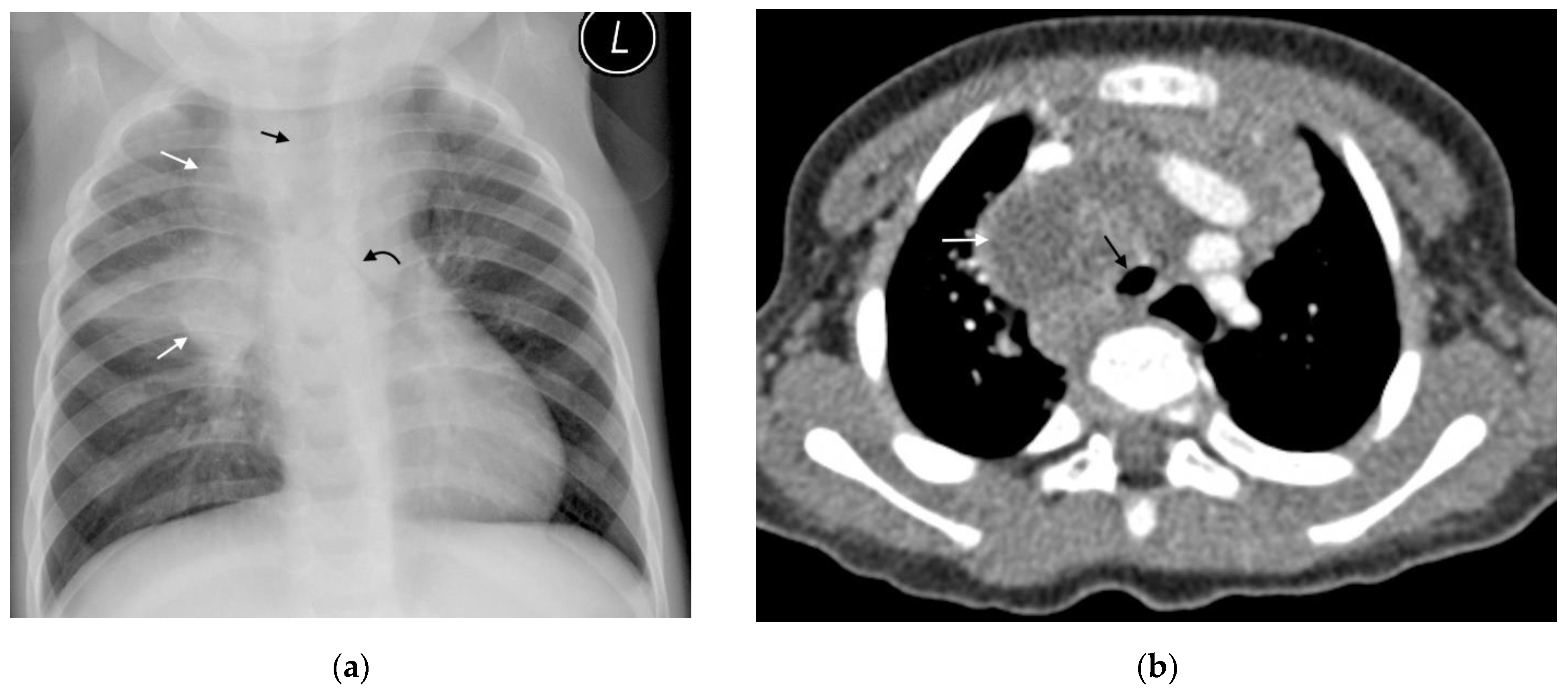

4.1. Progressive Adenopathy/Lymphotracheobronchial TB

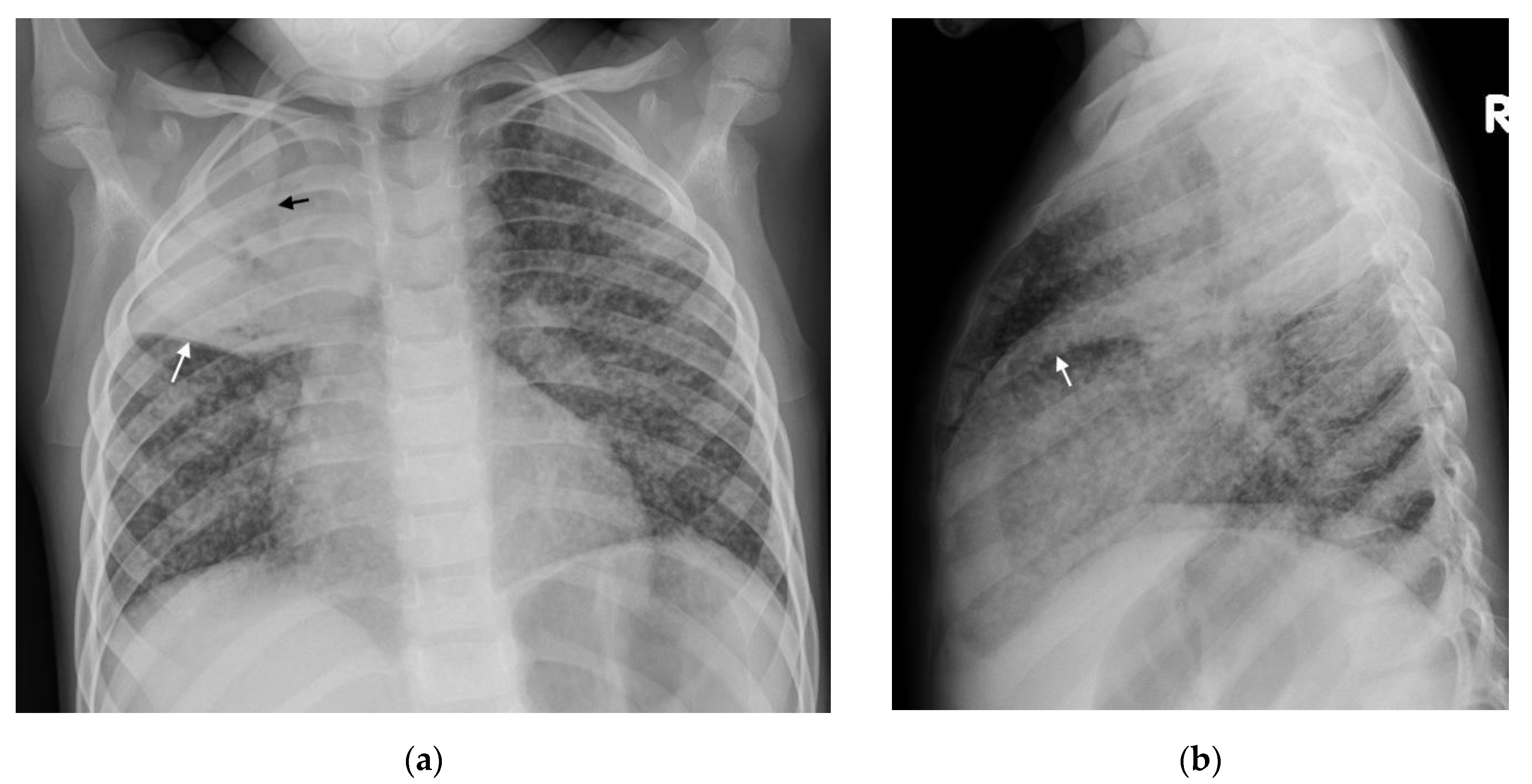

4.2. Airspace Disease

4.3. Miliary TB

5. Post Primary TB

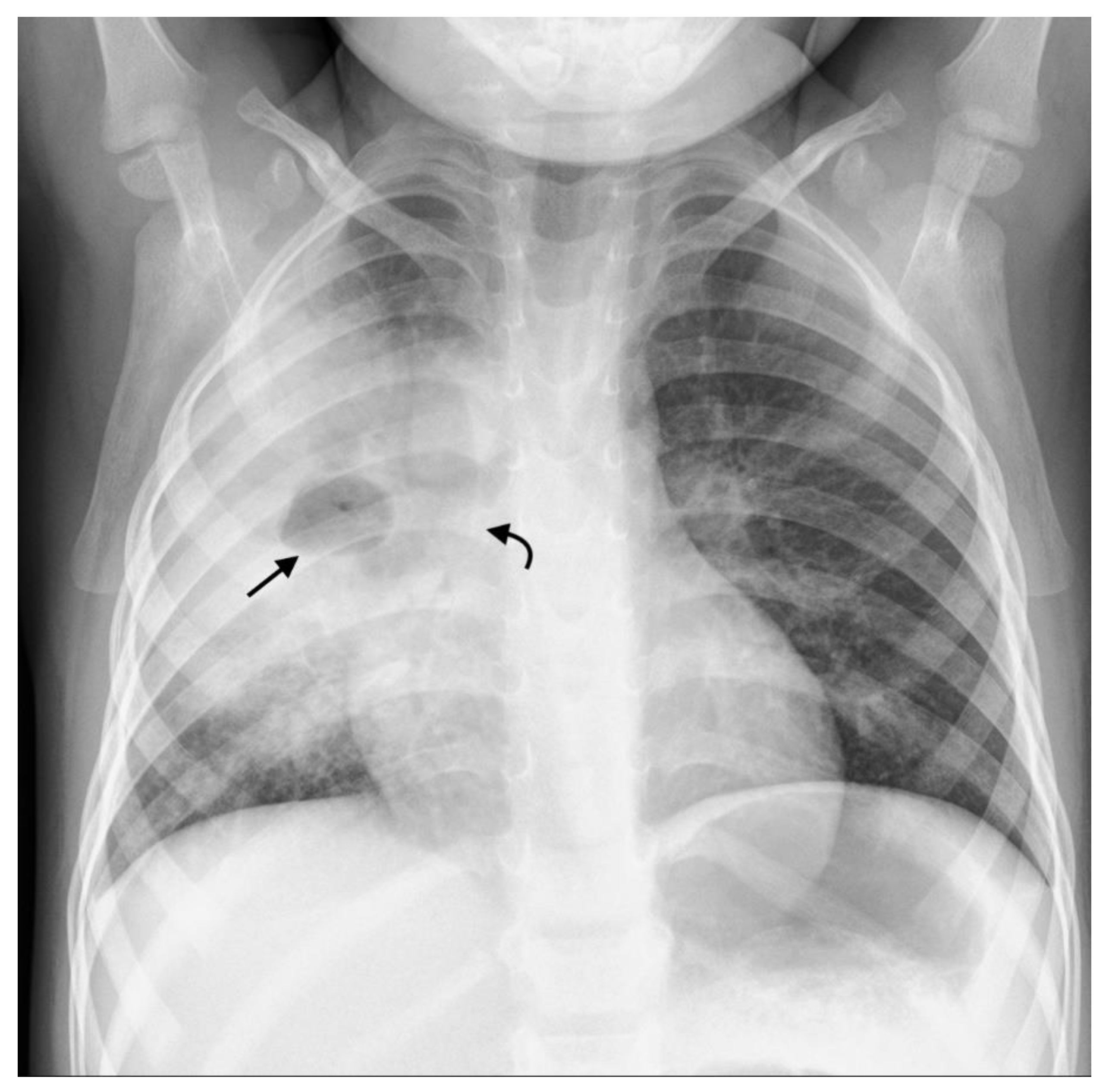

Cavitation

6. Complications

6.1. Bronchiectasis

6.2. Pleural Disease

6.3. Pericardial Disease

7. New Imaging Techniques/Technology

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Concepcion, N.D.P.; Laya, B.F.; Andronikou, S.; Daltro, P.A.N.; Sanchez, M.O.; Uy, J.A.U.; Lim, T.R.U. Standardized radiographic interpretation of thoracic tuberculosis in children. Pediatr. Radiol. 2017, 47, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pillay, T.; Andronikou, S.; Zar, H.J. Chest imaging in paediatric pulmonary TB. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2020, 36, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, K.S.; Bhalla, A.S.; Mahomed, N.; Laya, B.F. Imaging of thoracic tuberculosis in children: Current and future directions. Pediatr. Radiol. 2017, 47, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Villiers, R.V.; Andronikou, S.; Van de Westhuizen, S. Specificity and sensitivity of chest radiographs in the diagnosis of paediatric pulmonary tuberculosis and the value of additional high-kilovolt radiographs. Australas. Radiol. 2004, 48, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronikou, S.; Vanhoenacker, F.M.; De Backer, A.I. Advances in imaging chest tuberculosis: Blurring of differences between children and adults. Clin. Chest Med. 2009, 30, 717–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swingler, G.H.; du Toit, G.; Andronikou, S.; van der Merwe, L.; Zar, H.J. Diagnostic accuracy of chest radiography in detecting mediastinal lymphadenopathy in suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronikou, S.; van der Merwe, D.J.; Goussard, P.; Gie, R.P.; Tomazos, N. Usefulness of lateral radiographs for detecting tuberculous lymphadenopathy in children –confirmation using sagittal CT reconstruction with multiplanar cross-referencing. S. Afr. J. Rad. 2012, 16, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Andronikou, S.; Pillay, T.; Goussard, P.; Zar, H.J. Intrathoracic tuberculous lymphadenopathy in children: A guide to chest radiography. Pediatr. Radiol. 2017, 47, 277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du Toit, G.; Swingler, G.; Iloni, K. Observer variation in detecting lymphadenopathy on chest radiography. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2002, 6, 814–817. [Google Scholar]

- Heuvelings, C.C.; Bélard, S.; Andronikou, S.; Lederman, H.; Moodley, H.; Grobusch, M.P.; Zar, H.J. Chest ultrasound compared to chest X-ray for pediatric pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bélard, S.; Heuvelings, C.C.; Banderker, E.; Bateman, L.; Heller, T.; Andronikou, S.; Workman, L.; Grobusch, M.P.; Zar, H.J. Utility of point-of-care ultrasound in children with pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuvelings, C.C.; Bélard, S.; Familusi, M.A.; Spijker, R.; Grobusch, M.P.; Zar, H.J. Chest ultrasound for the diagnosis of paediatric pulmonary diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. BMB 2018, 129, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delacourt, C.; Mani, T.M.; Bonnerot, V.; de Blic, J.; Sayeg, N.; Lallemand, D.; Scheinmaann, P. Computed tomography with a normal chest radiograph in tuberculosus infection. Arch. Dis. Child. 1993, 69, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lucas, S.; Andronikou, S.; Goussard, P.; Gie, R. CT features of lymphobronchial tuberculosis in children, including complications and associated abnormalities. Pediatr. Radiol. 2012, 42, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.S.; Chan, P.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Shih, T.T. Computed tomography of children with pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2011, 110, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andronikou, S.; Joseph, E.; Lucas, S.; Brachmeyer, S.; Du Toit, G.; Zar, H.; Swingler, G. CT scanning for the detection of tuberculous mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr. Radiol. 2004, 34, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andronikou, S.; Lucas, S.; Zouvani, A.; Goussard, P. A proposed CT classification of progressive lungparenchymal injury complicating pediatric lymphobronchialtuberculosis: From reversible to irreversible lung injury. Pediatric. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 3657–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronikou, S.; Chopra, M.; Langton-Hewer, S.; Maier, P.; Green, J.; Norbury, E.; Price, S.; Smail, M. Technique, pitfalls, quality, radiation dose and findings of dynamic 4-dimensional computed tomography for airway imaging in infants and children. Pediatr. Radiol. 2019, 49, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salazar-Austin, N.; Ordonez, A.A.; Hsu, A.J.; E Benson, J.; Mahesh, M.; Menachery, E.; Razeq, J.H.; Salfinger, M.; Starke, J.R.; Milstone, A.M.; et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a young child after travel to India. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sodhi, K.S.; Lee, E.Y. What all physicians should know about the potential radiation risk that computed tomography poses for paediatric patients. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2014, 103, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, S.; Bhalla, A.S.; Jana, M. Pediatric Chest MRI: A Review. Indian J. Pediatrics 2019, 86, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, K.S.; Sharma, M.; Saxena, A.K.; Mathew, J.L.; Singh, M.; Khandelwal, M. MRI in Thoracic Tuberculosis of Children. Indian J. Pediatrics 2017, 84, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, K.S.; Ciet, P.; Vasanawala, S.; Biederer, J. Practical protocol for lung magnetic resonance imaging and common clinical indications. Pediatric. Radiol. 2021, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukund, A.; Khurana, R.; Bhalla, A.S.; Gupta, A.K.; Kabra, S.K. CT patterns of nodal disease in pediatric chest tuberculosis. World J. Radiol. 2011, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Pata, D.; Visconti, E.; Cirillo, G.; Rosella, F.; Pirronti, T.; Valentini, P. Chest CT Scan for the Diagnosis of Pediatric Pulmonary TB: Radiological Findings and Its Diagnostic Significance. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 583197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomà, P.; Lancella, L.; Menchini, L.; Lombardi, R.; Secinaro, A.; Villani, A. Radiological patterns of childhood thoracic tuberculosis in a developed country: A single institution’s experience on 217/255 cases. Radiol. Med. 2017, 122, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftakis, D.; Riaz, S.; Zumla, A.; Bomanji, J. Towards more accurate 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) imaging in active and latent tuberculosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 92, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moseme, T.; Andronikou, S. Through the eye of the suprasternal notch: Point-of-care sonography for tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr. Radiol. 2014, 44, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, K.-L.; Heuvelings, C.C.; Bélard, S.; Grobusch, M.P.; Zar, H.J.; Bulas, D.; Garra, B.; Andronikou, S. Technical aspects of mediastinal ultrasound for pediatric pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr. Radiol. 2017, 47, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Marcet, J.; Serres-Créixams, X.; Borrás-Pérez, V.; Coll-Sibina, M.T.; Guitet-Juliá, M.; Coll-Rosell, E. Value of sonography for follow-up of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in children with tuberculosis. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2007, 35, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Marcet, J.; Serres-Cr´eixams, X.; Zuasnabar-Cotro, A.; Codina-Puig, X.; CatalàPuigbó, M.; Simon-Riazuelo, J.L. Comparison of ultrasound with plain radiography and CT for the detection of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in children with tuberculosis. Pediatr. Radiol. 2004, 34, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, A.; Bhalla, A.S.; Jana, M.; Sharma, R. Overview of airway involvement in tuberculosis. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 57, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claes, A.S.; Clapuyt, P.; Menten, R.; Michoux, N.; Dumitriu, D. Performance of chest ultrasound in pediatric pneumonia. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 88, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, A.B.; Fortescue, R.; Grimwood, K.; Alexopoulou, E.; Bell, L.; Boyd, J.; Bush, A.; Chalmers, J.D.; Hill, A.T.; Karadag, B.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of children and adolescents with bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2002990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampoli, M.; Kappos, A.; Wolter, N.; von Gottberg, A.; Verwey, C.; Mamathuba, R.; Zar, H.J. Etiology and incidence of pleural empyema in South African children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Rapid Communication WHO Rapid Communication on Systematic Screening for Tuberculosis. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/rapid-communication-on-the-systematic-screening-for-tuberculosis (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Qin, Z.; Ahmed, S.; Sarker, M.S.; Paul, K.; Adel, A.S.S.; Naheyan, T.; Barrett, R.; Banu, S.; Creswell, J. Application of artificial intelligence in digital chest radiography reading for pulmonary tuberculosis screening. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Habib, S.S.; Zaidi, S.M.A.; Khowaja, S.; Khan, A.; Melendez, J.; Scholten, E.T.; Amad, F.; Schalekamp, S.; Verhagen, M.; et al. Computer aided detection of tuberculosis on chest radiographs: An evaluation of the CAD4TB v6 system. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Imaging Modality | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Chest radiograph | Widespread availability Low dose ionizing radiation Cost effective | Poor intra- and inter-observer agreement Poor sensitivity/specificity |

| Ultrasound | Performed at bedside | Requires user experience |

| Free of ionizing radiation Detects mediastinal nodes or pleural effusion before CXR Ability to assess for extrapulmonary TB | Sensitivity/specificity data for signs still scanty Unable to assess pulmonary hila for lymphadenopathy | |

| Computed tomography (CT) | Earlier more sensitive detection of TB disease and complications compared with CXR | Expensive Requires specific expertise |

| Ability to monitor disease complications and treatment response | Ionizing radiation although low dose protocols now in use | |

| Higher sensitivity for detecting nodes Allows for surgical planning Characterization of lymph node morphology and enhancement May differentiate TB from non-TB lymphadenopathy | Limited availability May require contrast | |

| Magnetic resonance Imaging (MRI) | Sensitivity/specificity comparable to CT (except small nodules/GGO) Differentiate TB lymphadenopathy from reactive lymph nodes based on signal intensity and heterogeneity | Expensive Requires specific expertise Limited availability May require sedation/anesthesia Longer scanning times (relative to other modalities) |

| Form of PTB | Imaging Findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Primary TB | Lymphadenopathy CXR: Lobulated hilar/paratracheal opacity. Potential for airway attenuation or deviation. Doughnut sign on lateral radiograph. US: Well defined round/oval hypoechoic (to thymic tissue and fat) nodes within the anterior and superior mediastinum. CT: Typically, low attenuation centrally with peripheral rim enhancement of node post contrast administration. Alternatively, matted conglomerate with ‘ghost-like’ rim enhancement. MRI: Low T2/STIR signal intensity nodes. Post gadolinium T1 images may demonstrate rim enhancement. | Right sided lymphadenopathy more common than left. CXR typically normal during incubation period. US unable to assess hilar region. CT detects nodes in a significant proportion of patients with normal CXR. Central low attenuation with peripheral enhancement helps distinguish from non-TB adenopathy. MRI comparable to CT in node detection over 3 mm. |

| Primary progressive TB | Progressive adenopathy CXR: Airway compression or displacement most reliable finding. Attenuation can result in distal ipsilateral hyperinflation, atelectasis or consolidation. US: Unable to assess airway compression but may detect distal complications. CT: Smooth luminal narrowing indicates extrinsic compression. Irregular narrowing may indicate erosion into lumen. Excellent for identifying complications, planning treatment and monitoring treatment response. MRI: Detection of compressive nodes and distal complications comparable to CT. Poorer resolution (in comparison with CT) makes airway lumen assessment and exact nodal location identification difficult. Airspace disease CXR: Opacification of lung parenchyma silhouetting adjacent structures. May display air bronchograms. US: Comparable detection rates to CXR with peripheral consolidation. Able to identify <0.5cm consolidation (usually undetectable on CXR). CT: Classic ‘tree-in-bud’ pattern. Central low attenuation non-enhancing regions represent caseous necrosis. MRI: Able to characterize TB consolidation. Consolidation in viable lung tissue demonstrates intermediate-to-high STIR signal. Low signal on STIR sequence indicates necrotic lung tissue. Miliary TB | Younger children more likely to develop nodal airway compression due to inherently narrower airways and weaker cartilaginous support structures. Airway attenuation is the most reliable CXR sign. Distal complications of airway compression include atelectasis, air-trapping, consolidation, necrosis and breakdown. Airway attenuation and characterization of complications better characterized by CT and MRI. Miliary TB best identified by presence of diffuse small nodules and thickened septal lines. CT is the superior imaging technique. |

| CXR: Often normal. Diffuse small non-calcified nodules. Thickened interlobular septal lines. US: No sensitive findings in children yet described. CT: Miliary nodules visualized well before visible on CXR. Small (<3 mm) randomly distributed nodules with thickened interlobular septa. MRI: Unable to detect <3 mm nodules. Useful in detecting lesions in solid organs (liver/spleen) | ||

| Post primary TB | Cavitation CXR: Often difficult to distinguish small cavity from consolidation. Airspace opacification surrounding an area of cavitation represents central caseous necrosis and liquefaction. Air-fluid level may represent secondary infection. CT: Central low-attenuating cavity. Cavity wall variable in size. Cavity surrounded by consolidation. MRI: Low signal cavity with surrounding consolidation. | Cavity formation is the hallmark of post-primary TB. Small cavities easily missed on CXR. CT and MRI superior to CXR in the detection of cavities. Usually predominate in upper lobes or apical segments of lower lobes. More common in adolescents. CT is useful in assessing cavity wall thickness. |

| Imaging Modality | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic 4-D CT scans | Accurately demonstrates tracheobronchomalacia. Demonstrates structures adjacent to the tracheobronchial tree. Non-invasive. Fast. Allows for 3D reconstruction. | Limited availability. Perceived to impart a higher radiation dose than bronchography. |

| Newer MRI techniques | Provide ventilation and perfusion images in a single acquisition. Shorter acquisition times. No radiation exposure. | High cost. Limited availability. |

| Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT | Highly sensitive in active TB. Reliably differentiates between active and latent disease. Assists with assessing response to treatment. | Limited availability. Low specificity with solitary pulmonary nodules. |

| Computer aided detection software (CAD) | Acceptable sensitivity (90%) and specificity (70%) of a TB triage test. Cost-effective. User friendly. No human expertise needed to interpret | Sparse literature regarding performance in paediatrics. Lower sensitivities in older patients and those with previous TB. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nel, M.; Franckling-Smith, Z.; Pillay, T.; Andronikou, S.; Zar, H.J. Chest Imaging for Pulmonary TB—An Update. Pathogens 2022, 11, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020161

Nel M, Franckling-Smith Z, Pillay T, Andronikou S, Zar HJ. Chest Imaging for Pulmonary TB—An Update. Pathogens. 2022; 11(2):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020161

Chicago/Turabian StyleNel, Michael, Zoe Franckling-Smith, Tanyia Pillay, Savvas Andronikou, and Heather J. Zar. 2022. "Chest Imaging for Pulmonary TB—An Update" Pathogens 11, no. 2: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020161

APA StyleNel, M., Franckling-Smith, Z., Pillay, T., Andronikou, S., & Zar, H. J. (2022). Chest Imaging for Pulmonary TB—An Update. Pathogens, 11(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020161