Chlamydia Peritonitis Mimicking Juvenile Carcinomatous Peritonitis Diagnosed by Exploratory Laparoscopy: A Case Report

Abstract

:1. Introduction

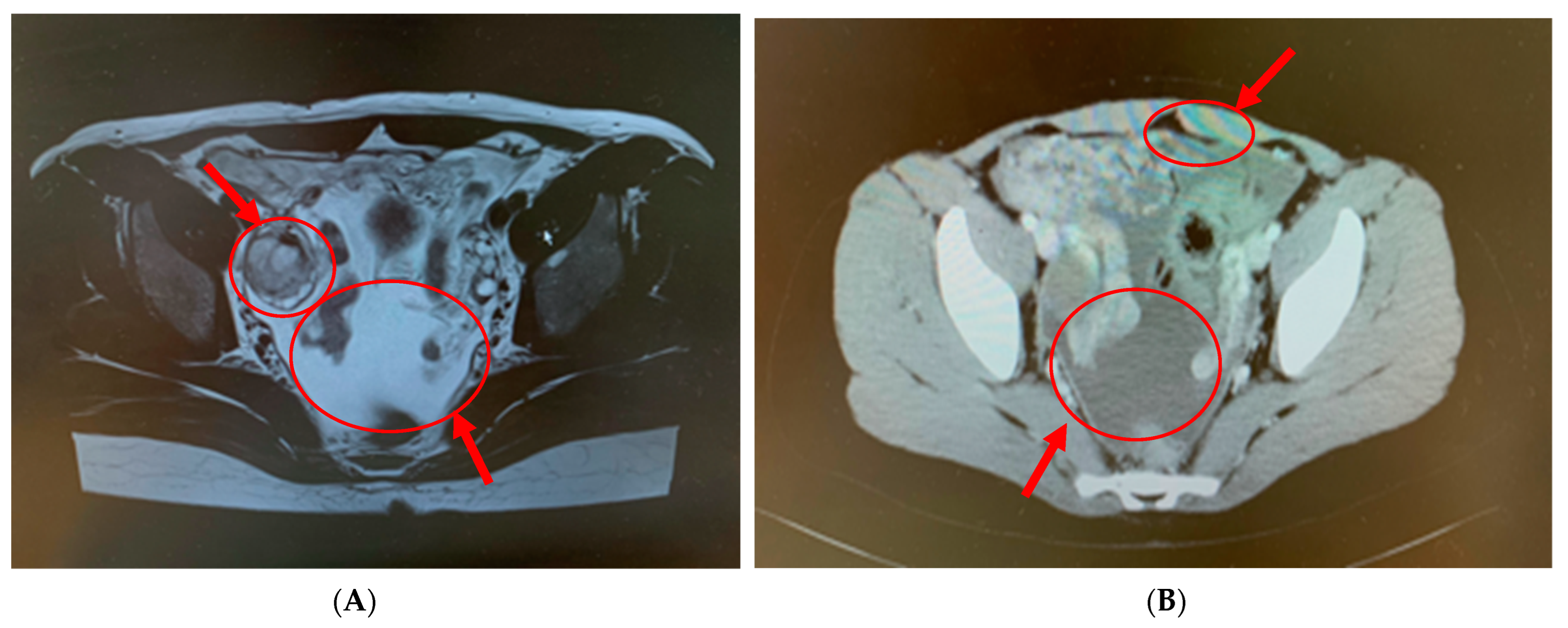

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA125 | carbohydrate antigen 125 |

| PID | pelvic inflammatory disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| ADA | adenosine deaminase |

References

- Kawado, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Ohta, A.; Oba, M.S.; Uehara, R.; Taniguchi, K.; Sunagawa, T.; Nagai, M.; Murakami, Y. Estimating nationwide cases of sexually transmitted diseases in 2015 from sentinel surveillance data in Japan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, K.N.; Nielsen-Saines, K.; Klausner, J.D. Chlamydia trachomatis screening and treatment in pregnancy to reduce adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: A review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 531073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gojayev, A.; English, D.P.; Macer, M.; Azodi, M. Chlamydia peritonitis and ascites mimicking ovarian cancer. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 2016, 8547173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Institute for Infectious Disease. Implementation Manual for the National Epidemiological Surveillance of Infectious Diseases Program. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000488981.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Pavlin, N.L.; Parker, R.; Fairley, C.K.; Gunn, J.M.; Hocking, J. Take the sex out of STI screening! Views of young women on implementing chlamydia screening in General Practice. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kang, H.M.; Oh, T.H.; Kang, G.H.; Joen, T.J.; Seo, D.D.; Shin, W.C.; Choi, W.C.; Yang, K.H. A case of Chlamydia trachomatis peritonitis mimicking tuberculous peritonitis. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 58, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ugianskiene, A. Chlamydial infection with marked ascites that simulated ovarian cancer. Ugeskr. Laeger 2013, 75, 963–965. [Google Scholar]

- Contini, C.; Rotondo, J.C.; Magagnoli, F.; Maritati, M.; Seraceni, S.; Graziano, A.; Poggi, A.; Capucci, R.; Vesce, F.; Tognon, M.; et al. Investigation on silent bacterial infections in specimens from pregnant women affected by spontaneous miscarriage. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 234, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Debonnet, C.; Robin, G.; Prasivoravong, J.; Vuotto, F.; Catteau-Jonard, S.; Faure, K.; Dessein, R.; Robin, C. Update of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2021, 49, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.T.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, Y.M.; Moon, H.M.; Rhim, C.C. Clinical characteristics of genital chlamydia infection in pelvic inflammatory disease. BMC Women’s Health 2017, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Contini, C.; Seraceni, S. Chlamydial Diseasa: A Crossroad Between Chronic Infection and Development of Cancer. Bact. Cancer 2011, 16, 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Contini, C.; Seraceni, S.; Carradori, S.; Cultrera, R.; Perri, P.; Lanza, F. Identification of Chlamydia trachomatis in a patient with ocular lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2009, 84, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nishida, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Takehara, K.; Yatsuki, K.; Ichinose, T.; Ishida, T.; Hiraike, H.; Sasajima, Y.; Nagasaka, K. Chlamydia Peritonitis Mimicking Juvenile Carcinomatous Peritonitis Diagnosed by Exploratory Laparoscopy: A Case Report. Pathogens 2023, 12, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12010094

Nishida H, Takahashi Y, Takehara K, Yatsuki K, Ichinose T, Ishida T, Hiraike H, Sasajima Y, Nagasaka K. Chlamydia Peritonitis Mimicking Juvenile Carcinomatous Peritonitis Diagnosed by Exploratory Laparoscopy: A Case Report. Pathogens. 2023; 12(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleNishida, Haruka, Yuko Takahashi, Kohei Takehara, Keita Yatsuki, Takayuki Ichinose, Tsuyoshi Ishida, Haruko Hiraike, Yuko Sasajima, and Kazunori Nagasaka. 2023. "Chlamydia Peritonitis Mimicking Juvenile Carcinomatous Peritonitis Diagnosed by Exploratory Laparoscopy: A Case Report" Pathogens 12, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12010094