The Impact of Climate on Human Dengue Infections in the Caribbean

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Bibliographic Search

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Search String

2.4. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

3. Results

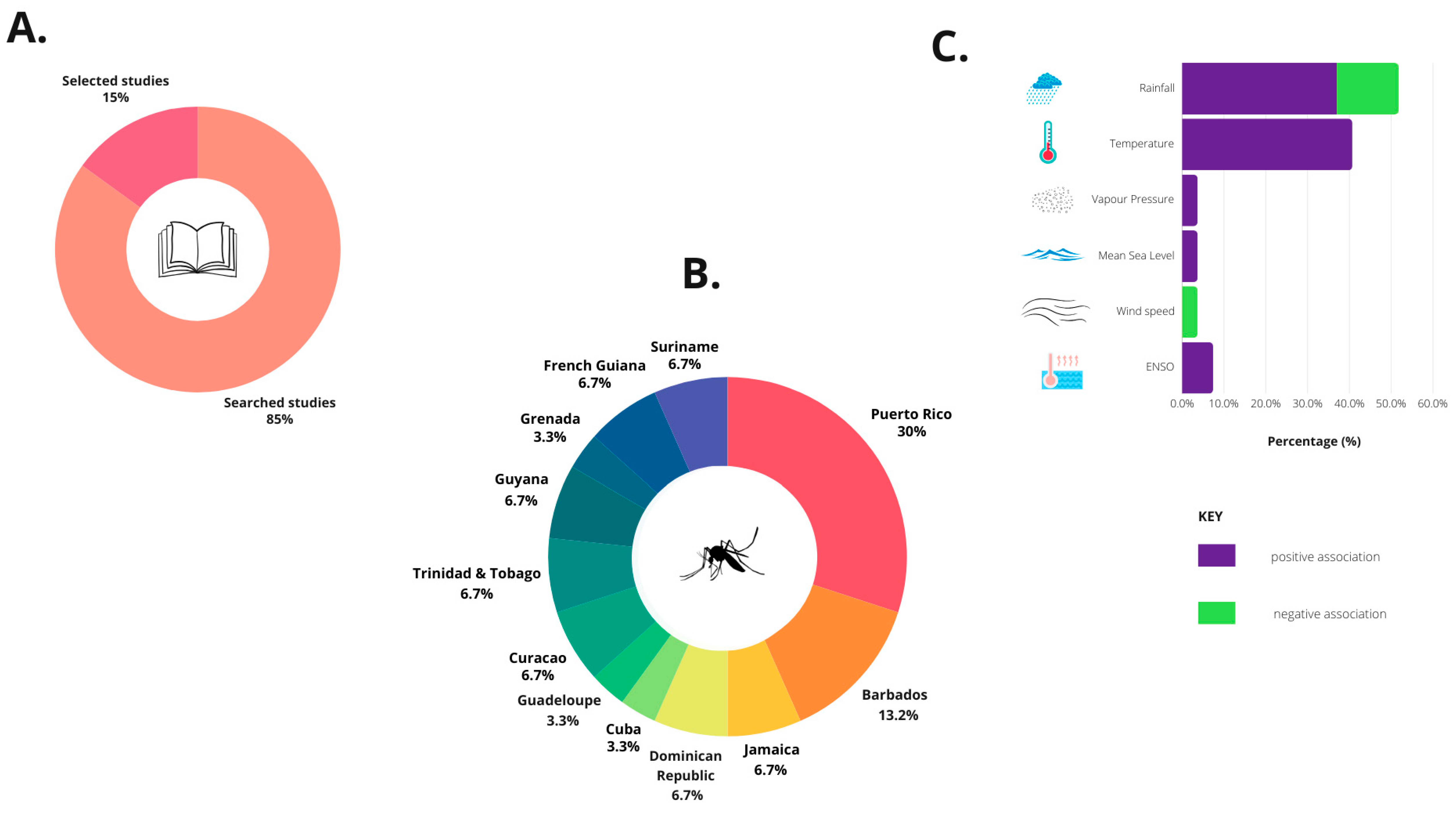

3.1. Bibliographic Search

3.2. Selected Studies

| Study | Quality | Study Location | Study Design | Time Period | Climatic Variables | Outcome | CO-FACTORS | Statistical Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keating et al., 2001 [52] | + | Puerto Rico | Multivariate linear regression | 1988–1992 | Seasonal temperatures | Dengue cases | None | Regression analysis and Durbin–Watson test | Temperature has a positive effect on dengue cases reported each month with a lag of 12 weeks or 3 months. Other factors may be influencing seasonal dengue incidence. |

| Schreiber et al., 2001 [53] | + | Multivariate stochastic models | 1988–1993 | Temperature, rainfall | Dengue cases | None | Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient | The mean seasonal variation in dengue is highly related (R2 = 88.1%) to the mean seasonal climate variation, with those thermal and energy variables immediately preceding the dengue response showing the strongest relationships. However, moisture variables, predominantly in the form of surplus, are more influential many weeks in advance. For the interannual model (R2 = 44.1%), energy change, thermal change, and moisture variables are significant across the 8-week period, with moisture variables playing a stronger role than in the intra-annual model. | |

| Jury, 2008 [38] | + | Bayesian model | 1979–2005 | Rainfall, wind speed, temperature, and air pressure | Dengue cases | None | K function analysis and Barton David Knox | A positive association of rainfall with dengue was observed with no appreciable lag time. While temperature was positively associated with year-to-year variability of dengue cases. | |

| Johansson et al., 2009a [39] | ++ | DLM | 1986–2006 | Temperature and rainfall | Dengue cases | Social vulnerability (household income and % persons below poverty line) | 95% CI | Temperature influences dengue incidence in cooler mountain regions. Rainfall’s strongest influence is in the dry southwestern coast. Areas with higher poverty index had more dengue cases. | |

| Johansson et al., 2009b [40] | ++ | Wavelet analysis | 1993–2016 | Temperature, precipitation, and ENSO index | Dengue cases | None | Monte Carlo test of duration | Temperature and rainfall strongly coherent with dengue with 1 y periodicity. A strong link with ENSO and dengue incidence was observed from 1995 to 2002 but must be taken cautiously. | |

| Méndez-Lázaro et al., 2014 [41] | + | Puerto Rico | PCA and bivariate analysis | 1995–2009 | SLP, MSL, Temperature, Wind, SST, and rainfall | Dengue cases | None | Pearson’s correlation, Mann–Kendall trend test, and logistic regressions | A positive association of precipitation and forested and scrubland habitats with dengue cases was observed. |

| Buczak et al., 2018 [54] | + | SARIMA and Ensemble models | 1990–2009 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | RMSE and MAE | Mixed results for Puerto Rico | ||

| Puggioni et al., 2020 [55] | ++ | Hierarchical Bayesian | 1990–2004 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | Spatiotemporal factors | RMSE | ||

| Nova et al., 2021 [42] | ++ | Empirical Dynamic Modeling | 1990–2009 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | Susceptibles index (λ) | Pearson’s correlation coefficient and RMSE | Rainfall and susceptibles index were significant drivers of dengue incidence beyond seasonality. However, temperature was not a significant driver beyond seasonality. High host susceptibility allows seasonal climate suitability to fuel large dengue epidemics in San Juan, Puerto Rico. | |

| Depradine and Lovell, 2004 [33] | + | Barbados | Lagged cross-correlation and multiple regression analysis | 1995–2000 | Rainfall, temperature, and VP | Dengue cases | None | 99% CI | VP had the strongest correlation with dengue cases at 6 weeks lag, minimum temperature at 12 weeks lag and max. temperature at 16 weeks lag while there was a negative correlation with wind speed and rainfall with dengue cases. |

| Parker and Holman, 2014 [51] | ++ | Logistic model | 1992–1996 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | Drought, floods, and storms | CI, SE, and AIC | Mean monthly temperature was the most important factor affecting the duration of both inter-epidemic spells (β = 0.543; confidence interval (CI) 0.4954, 0.5906) and epidemic spells (β = −0.648; CI −0.7553, −0.5405). Drought conditions increased the time between epidemics. Increased temperature hastened the onset of an epidemic, and during an epidemic, higher mean temperature increased the duration of the epidemic. | |

| Lowe et al., 2018 [37] | ++ | Barbados | DLNM and Bayesian model | 1999–2016 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | None | Area under the curve ROC (AUC) | Low rainfall/drought is positively associated with dengue incidence and increased rainfall after 1–5 months of drought. Failure to predict 2 outbreak peaks of CHIKV and ZIKV. |

| Douglas et al., 2020 [43] | + | Cross-sectional epidemiology | 2008–2016 | Seasonality (rainfall) | Dengue cases | Age, sex, and location | 95% CI | Peak dengue incidence was observed during the wet season. | |

| Henry and de Assi Mendonça et al., 2020 [56] | + | Jamaica | WADI | 1995–2018 | Rainfall, temperature, and LST | Dengue cases | WADI Socioeconomic (GIS, urban, and RCP) | SCME | High vulnerability in urban vs. rural areas, expansion to higher latitudes. RCP8.5 |

| Francis et al., 2023 [36] | + | Grenada | Negative binomial regression | 2010–2020 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | None | 95% CI | In 2013, 2018, and 2020, the driest years, the highest number of DF cases were observed. Other factors may explain these high numbers of DF cases: (1) frequent sporadic heavy rainfall and (2) poor water storage practices in dry season. |

| Petrone et al., 2021 [32] | ++ | Dominican Republic | Index P (Bayesian) | 2012–2018 | Temperature and relative humidity | Dengue cases | Reff, AaS scores, CHIKV, and ZIKV | Pearson’s R correlation coefficient | Temperature and humidity analysis (Index P) showed that dengue outbreaks peaked after a period characterized by high transmission potential, just as transmission potential was beginning to wane. Variability in seasonal weather patterns and vectorial capacity did not account for differences in the timing of emerging disease outbreaks. |

| Bultó et al., 2006 [57] | + | Cuba | EOF | 1961–2003 | Temperature, rainfall, VP, and relative humidity | Dengue cases | Bultó index, life quality, and degree of poverty | EOF analysis | More frequent outbreaks, changes in seasons and spatial patterns, and less climate variability inland were observed. |

| Díaz-Quijano and Waldman, 2012 [44] | + | Spanish-speaking Caribbean and Non-Spanish-speaking Caribbean | Poisson regression | 1995–2009 | Rainfall | Dengue cases | HDI, population density, per capita GEH | 95% CI | Rainfall, the sole climatic variable investigated, was associated with dengue mortality (RR = 1.9 [per 103 L/m2]; 95% CI = 1.78–2.02) along with population density. |

| Gharbi et al., 2011 [50] | ++ | Guadeloupe | SARIMA | 2000–2007 | Temperature, humidity, and rainfall | Dengue cases | None | RMSE, Wilcoxon signed ranks test, and Pearson’s correlation | Temperature was associated with increased model predictability of dengue incidence forecasting more than rainfall and humidity. Rainfall was not correlated. Minimum temperature at lag 5 weeks was best—RMSE = 0.72. |

| Limper et al., 2016 [49] | ++ | Curaçao | DNLM and GAM | 1999–2009 | Temperature, humidity, and rainfall | Dengue cases | None | 95% CI and RR, chi-squared test, and RR | Increases in mean temperature are associated with lower dengue incidence but lower temperatures with higher dengue incidence. Rainfall decreased dengue incidence. |

| Limper et al., 2010 [34] | + | Non-parametric Spearman’s correlation test | 1999–2009 | Temperature, rainfall, and humidity | Dengue cases | None | Non-parametric Spearman’s correlation test | ||

| Chadee et al., 2007 [45] | + | Trinidad | Population-based | 2002–2004 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | Breteau index | None | Rainfall strongly correlated with dengue disease but no correlation with temperature. |

| Amarakoon et al., 2008 [48] | ++ | Trinidad, Barbados, and Jamaica | Correlation analysis including lag | 1980–2003 | Rainfall and temperature | Dengue cases | MAT, AMAT, At, and Dot | Correlation coefficient (r) | The yearly patterns of dengue exhibited a well-defined seasonality, with epidemics occurring in the latter half of the year following the onset of rainfall and increasing temperature and a higher probability of epidemics occurring during El Niño periods. |

| Boston and Kurup, 2017 [46] | + | Guyana | Correlation analysis | 2009–2014 | Rainfall, temperature, and humidity | Dengue cases | Malaria and leptospirosis | Pearson’s R correlation and correlation coefficient (r) | Rainfall strongly associated with dengue incidence but not temperature and humidity. |

| Ferreira et al., 2014 [58] | + | Guyana, Suriname, Cuba, and multiple Caribbean countries | Correlation analysis | 1995–2004 | ENSO index | Dengue cases | South Oscillation index (SOI) | Correlation coefficients (r) | A higher DF incidence was noted in Cuba, confirming a possible positive ENSO influence. |

| Gagnon et al., 2001 [47] | + | Suriname and French Guiana | Correlation analysis | 1965–1992 | Rainfall, temperature, and ENSO cycles | Dengue cases | Monthly river height | Fisher’s exact test, Fisher’s z-transformation, and Quenouille’s method | A statistically significant relationship was observed between El Niño and dengue epidemics in Colombia, French Guiana, Indonesia, and Surinam. The number of DHF cases is highest when a prolonged drought precedes the rainy season. |

| Adde et al., 2016 [35] | ++ | French Guiana | Lagged correlation and logistic regression | 1991–2013 | SST and SLP | Dengue cases | SOI and MEI | Student’s t test, Spearman’s lagged correlation, AIC, and AUC | The climatic indices assessed in this study were important for DF monitoring and for predicting outbreaks in French Guiana over a period of 2–3 months. An important rainfall deficit at the end of the dry season enhances the risk of epidemic in the following year. |

| Study | Quality | Study Location | Study Design | Statistical Methods | Metric | Best Model Value | Worst Model Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keating et al., 2001 [52] | ++ | Puerto Rico | Multivariate linear regression | Regression analysis and Durbin–Watson test | R-squared | 0.71 | 0.62 |

| F-value | 49.94 | 67.22 | |||||

| SE | 102.8 | 116.9 | |||||

| Schreiber et al., 2001 [53] | ++ | Multivariate stochastic models | Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient | Adjusted R-squared | 0.88 | 0.14 | |

| Jury, 2008 [38] | + | 0.02 | 0.0001 | ||||

| Johansson et al., 2009a [39] | + | Poisson regression models | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Johansson et al., 2009b [40] | + | Wavelet analysis | Monte Carlo (MC) significance | MC significance | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| Méndez-Lárazo et al., 2014 [41] | + | Principal Component Analysis | Logistic regression | p-value | N/A | N/A | |

| Pearson correlation coefficient | |||||||

| Mann–Kendall trend test | |||||||

| Logistic regression | |||||||

| Buczak et al., 2018 [54] | ++ | SARIMA and Ensemble models | Time series methods | Log loss | −1.8 | −6.4 | |

| Puggioni et al., 2020 [55] | ++ | Hierarchical Bayesian | Mean squared error | 8.632 | 14,055.18 | ||

| Mean absolute percentage error | 2.663 | 372.01 | |||||

| Mean absolute error | 2.228 | 86.56 | |||||

| Relative bias | −0.001 | 0.49 | |||||

| Relative mean separation | 0.436 | 0.97 | |||||

| Root mean squared error | 2.951 | 118.11 | |||||

| Nova et al., 2021 [42] | ++ | Empirical Dynamic Modeling | Correlation analysis | Pearson’s correlation coefficient | 0.9697 | 0.38 | |

| Root mean squared error | 37.14 | 57.34 | |||||

| Depradine and Lovell, 2004 [33] | + | Barbados | |||||

| Lagged cross-correlation and multiple regression analysis | Correlation analysis | Pearson’s correlation coefficient | 0.7 | 0.25 | |||

| Parker and Holman, 2014 [51] | ++ | Logistic model | Akaike information criterion (AIC) and 99% CI | N/A (no comparison made) | N/A | N/A | |

| Standard error | 0.0001 | 172.4 | |||||

| Lowe et al., 2018 [37] | ++ | DLNM and Bayesian model | Area under the curve ROC (AUC) | AUC | 0.90 | 0.75 | |

| Likelihood ratio R-squared | R2_LR | 0.68 | 0.23 | ||||

| Deviance information criterion | DIC | 1664.94 | 1801.36 | ||||

| Barbados | |||||||

| Douglas et al., 2020 [43] | + | Cross-sectional epidemiology | 95% CI | CI | N/A | N/A | |

| Henry and de Assi Mendonça et al., 2020 [56] | + | Jamaica | Water-Associated Disease Index | Color-coded vulnerability | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Amarakoon et al., 2008 [48] | + | Time series analysis | Correlation analysis | Pearson’s correlation coefficient | >0.71 | N/A | |

| Francis et al., 2023 [36] | + | Grenada | Negative binomial regression | 95% CI | CI | N/A | N/A |

| Díaz-Quijano and Waldman, 2012 [44] | ++ | Cuba | Poisson regression | Correlation coefficient, rate ratio, CI | Pseudo R2 | 49.8% | 48.3% |

| Bultó et al., 2006 [57] | ++ | Statistical variability analysis | Bultó index | IB index | 18.77 | 1109 | |

| Boston and Kurup, 2017 [46] | + | Guyana | Correlation and regression analysis | Correlation coefficient | r | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Ferreira et al., 2014 [58] | + | Guyana, Belize, Suriname, Cuba, and multiple Caribbean countries | Frequency analysis | Annual dengue frequency | Mean annual frequency | 18.27 | N/A |

| Adde et al., 2016 [35] | ++ | French Guiana | Logistic binomial regression model | Akaike information criterion (AIC) | AIC | 27 | 31 |

| Area under curve (AUC) | AUC | 0.88 | 0.75 | ||||

| Standard error | SE | 0.02 | 1.42 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Rainfall or Precipitation Factor

4.2. Temperature Factor

4.3. Multiple Co-Factors

4.3.1. Mosquito Vector Distribution

4.3.2. Human and Social Factors

4.3.3. Infrastructure

4.3.4. Travel and Trade

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- A.

- Validity of Study Results

- Was a clear focus issue addressed?—Yes/Unsure/NoFollow on and ask some of these other questions to evaluate the rating.

- Which study design was utilized?

- Was the appropriate method used to answer the question posed?

- Was/Were the climate exposure factor(s) accurately measured to minimize bias?

- Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias?

- Were all the important confounding factors identified?

- Are these confounding factors addressed in the design and or analysis?

- B.

- What are the Study Results?

- What are the results of this study?—Yes/Unsure/NoFollow and ask some of these other questions to evaluate the rating.

- What is the level of precision of the results? What is the level of precision for the risk estimate used?

- Are the results believable based on statistics?

- How was this study funded?

- C.

- Applicability of Study Results to This Systematic Review

- Does this study answer the question posed by this systematic review?—Yes/Unsure/NoFollow on and ask some of these other questions to evaluate the rating.

- What is the level of precision of the results? What is the level of precision for the risk estimate used?

- Are the results believable?

References

- Murray, N.E.A.; Quam, M.B.; Wilder-Smith, A. Epidemiology of dengue: Past, present and future prospects. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 5, 299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vasilakis, N.; Cardosa, J.; Hanley, K.A.; Holmes, E.C.; Weaver, S.C. Fever from the forest: Prospects for the continued emergence of sylvatic dengue virus and its impact on public health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattarino, L.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Imai, N.; Cummings, D.A.; Ferguson, N.M. Mapping global variation in dengue transmission intensity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweileh, W.M. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature on climate change and human health with an emphasis on infectious diseases. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añez, G.; Volkova, E.; Jiang, Z.; Heisey, D.A.; Chancey, C.; Fares, R.C.; Rios, M.; Group, C.S. Collaborative study to establish World Health Organization international reference reagents for dengue virus Types 1 to 4 RNA for use in nucleic acid testing. Transfusion 2017, 57, 1977–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAHO. PAHO Urges Countries to Strengthen Dengue Prevention in Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean; Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO): Washington DC, USA, 2024; Website; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/24-5-2024-paho-urges-countries-strengthen-dengue-prevention-central-america-mexico-and#:~:text=As%20of%20mid%2DMay%202024,%2C%20Peru%2C%20Colombia%20and%20Mexico (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- BGIS. Health Ministry’s Updates on Dengue Fever, Gastro & Respiratory Illnesses Government Blog Update; Barbados Government Information Service (BGIS): Saint Michael, Barbados, 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.bb/News/Press-Releases/Health-Ministry-s-Updates-On-Dengu#:~:text=Up%20to%20the%20week%20ending,cases%2C%20and%20105%20confirmed%20cases (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Ramos-Castaneda, J.; Barreto dos Santos, F.; Martinez-Vega, R.; Galvão de Araujo, J.M.; Joint, G.; Sarti, E. Dengue in Latin America: Systematic review of molecular epidemiological trends. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.I.; Richardson, J.H.; Sánchez-Vargas, I.; Olson, K.E.; Beaty, B.J. Dengue virus type 2: Replication and tropisms in orally infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Xiang, B.W.; Saron, W.A.; Stewart, J.C.; Hain, A.; Walvekar, V.; Missé, D.; Thomas, F.; Kini, R.M.; Roche, B.; Claridge-Chang, A. Dengue virus infection modifies mosquito blood-feeding behavior to increase transmission to the host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117589119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I. Islandness within climate change narratives of small island developing states (SIDS). Isl. Stud. J. 2018, 13, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukuitonga, C.; Vivili, P. Climate effects on health in Small Islands Developing States. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e69–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.O.; Payne, K.; Sabino-Santos, G., Jr.; Agard, J. Influence of climatic factors on human hantavirus infections in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. Pathogens 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.J.; Canziani, O.F.; Leary, N.A.; Dokken, D.J.; White, K.S. Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, M.; Parry, M.L.; Canziani, O.; Palutikof, J.; Van der Linden, P.; Hanson, C. Climate Change 2007—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, A.; Nurse, L.; John, C. Climate change in the Caribbean: The water management implications. J. Environ. Dev. 2010, 19, 42–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Elbal, P.M.; Rodríguez-Sosa, M.A.; Ruiz-Matuk, C.; Tapia, L.; Arredondo Abreu, C.A.; Fernández González, A.A.; Rodríguez Lauzurique, R.M.; Paulino-Ramírez, R. Breeding Sites of Synanthropic Mosquitoes in Zika-Affected Areas of the Dominican Republic. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2021, 37, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.A.; Clarke, L.A.; Centella, A.; Bezanilla, A.; Stephenson, T.S.; Jones, J.J.; Campbell, J.D.; Vichot, A.; Charlery, J. Future Caribbean climates in a world of rising temperatures: The 1.5 vs 2.0 dilemma. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 2907–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, S.; Hinds, A.; Rawlins, J. Malaria and its vectors in the Caribbean: The continuing challenge of the disease forty-five years after eradication from the islands. West Indian Med. J. 2008, 57, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Toan, N.T.; Rossi, S.; Prisco, G.; Nante, N.; Viviani, S. Dengue epidemiology in selected endemic countries: Factors influencing expansion factors as estimates of underreporting. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 840–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón-González, F.J.; Peres, C.A.; Steiner São Bernardo, C.; Hunter, P.R.; Lake, I.R. After the epidemic: Zika virus projections for Latin America and the Caribbean. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, C.A.; Stewart-Ibarra, A.M.; Romero, M.; Lowe, R.; Mahon, R.; Van Meerbeeck, C.J.; Rollock, L.; Hilaire, M.G.-S.; Trotman, A.R.; Holligan, D. Spatiotemporal tools for emerging and endemic disease hotspots in small areas: An analysis of dengue and chikungunya in Barbados, 2013–2016. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Escobar, G.; Churaman, C.; Rampersad, C.; Singh, R.; Nathaniel, S. Mayaro virus detection in patients from rural and urban areas in Trinidad and Tobago during the Chikungunya and Zika virus outbreaks. Pathog. Glob. Health 2021, 115, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, I.; Salje, H.; Saha, S.; Gurley, E.S. Seasonal Distribution and Climatic Correlates of Dengue Disease in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 1359–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, T.; Jiang, L. Why Does a Stronger El Niño Favor Developing towards the Eastern Pacific while a Stronger La Niña Favors Developing towards the Central Pacific? Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, B.; Vos, D.; Halabi, Y.; Gerstenbluth, I.; Duits, A.; Grillet, M.E.; Tami, A.; Vincenti-Gonzalez, M.F. Spatial and temporal trends of dengue infections in Curaçao: A 21-year analysis. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2024, 24, e00338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazelles, B.; Cazelles, K.; Tian, H.; Chavez, M.; Pascual, M. Disentangling local and global climate drivers in the population dynamics of mosquito-borne infections. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, S.J.; Lippi, C.A.; Caplan, T.; Diaz, A.; Dunbar, W.; Grover, S.; Johnson, S.; Knowles, R.; Lowe, R.; Mateen, B.A. The current landscape of software tools for the climate-sensitive infectious disease modelling community. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e527–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littell, J.H.; Corcoran, J.; Pillai, V. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roda Gracia, J.; Schumann, B.; Seidler, A. Climate variability and the occurrence of human puumala hantavirus infections in Europe: A systematic review. Zoonoses Public Health 2015, 62, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocker, T. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Petrone, M.E.; Earnest, R.; Lourenço, J.; Kraemer, M.U.; Paulino-Ramirez, R.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Tapia, L. Asynchronicity of endemic and emerging mosquito-borne disease outbreaks in the Dominican Republic. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depradine, C.; Lovell, E. Climatological variables and the incidence of Dengue fever in Barbados. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2004, 14, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limper, M.; Van de Weg, C.; Koraka, P.; Halabi, Y.; Gerstenbluth, I.; Boekhoudt, J.; Martis, A.; Martina, B.; Duits, A.; Osterhaus, A. The 2008 dengue epidemic on Curaçao: Correlation with climatological factors. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e376–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adde, A.; Roucou, P.; Mangeas, M.; Ardillon, V.; Desenclos, J.-C.; Rousset, D.; Girod, R.; Briolant, S.; Quenel, P.; Flamand, C. Predicting dengue fever outbreaks in French Guiana using climate indicators. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, K.; Edwards, O.; Telesford, L. Climate and dengue transmission in Grenada for the period 2010–2020: Should we be concerned? PLOS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Gasparrini, A.; Van Meerbeeck, C.J.; Lippi, C.A.; Mahon, R.; Trotman, A.R.; Rollock, L.; Hinds, A.Q.; Ryan, S.J.; Stewart-Ibarra, A.M. Nonlinear and delayed impacts of climate on dengue risk in Barbados: A modelling study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jury, M.R. Climate influence on dengue epidemics in Puerto Rico. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2008, 18, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.A.; Dominici, F.; Glass, G.E. Local and global effects of climate on dengue transmission in Puerto Rico. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.A.; Cummings, D.A.; Glass, G.E. Multiyear climate variability and dengue—El Nino southern oscillation, weather, and dengue incidence in Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Thailand: A longitudinal data analysis. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Lazaro, P.; Muller-Karger, F.E.; Otis, D.; McCarthy, M.J.; Pena-Orellana, M. Assessing climate variability effects on dengue incidence in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9409–9428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nova, N.; Deyle, E.R.; Shocket, M.S.; MacDonald, A.J.; Childs, M.L.; Rypdal, M.; Sugihara, G.; Mordecai, E.A. Susceptible host availability modulates climate effects on dengue dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, K.O.; Dutta, S.K.; Martina, B.; Anfasa, F.; Samuels, T.A.; Gittens-St. Hilaire, M. Dengue fever and severe dengue in Barbados, 2008–2016. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Quijano, F.A.; Waldman, E.A. Factors associated with dengue mortality in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1995–2009: An ecological study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 86, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadee, D.; Shivnauth, B.; Rawlins, S.; Chen, A. Climate, mosquito indices and the epidemiology of dengue fever in Trinidad (2002–2004). Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2007, 101, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, C.; Kurup, R. Estimated Effects of Climate Variables on Transmission of Malaria, Dengue and Leptospirosis within Georgetown, Guyana. West Indian Med. J. 2017, 65, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, A.S.; Bush, A.B.; Smoyer-Tomic, K.E. Dengue epidemics and the El Niño southern oscillation. Clim. Res. 2001, 19, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarakoon, D.; Chen, A.; Rawlins, S.; Chadee, D.D.; Taylor, M.; Stennett, R. Dengue epidemics in the Caribbean-temperature indices to gauge the potential for onset of dengue. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2008, 13, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limper, M.; Thai, K.; Gerstenbluth, I.; Osterhaus, A.; Duits, A.; van Gorp, E. Climate factors as important determinants of dengue incidence in Curaçao. Zoonoses Public Health 2016, 63, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharbi, M.; Quenel, P.; Gustave, J.; Cassadou, S.; Ruche, G.L.; Girdary, L.; Marrama, L. Time series analysis of dengue incidence in Guadeloupe, French West Indies: Forecasting models using climate variables as predictors. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Holman, D. Event history analysis of dengue fever epidemic and inter-epidemic spells in Barbados, Brazil, and Thailand. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, e793–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, J. An investigation into the cyclical incidence of dengue fever. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, K.V. An investigation of relationships between climate and dengue using a water budgeting technique. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2001, 45, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczak, A.L.; Baugher, B.; Moniz, L.J.; Bagley, T.; Babin, S.M.; Guven, E. Ensemble method for dengue prediction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puggioni, G.; Couret, J.; Serman, E.; Akanda, A.S.; Ginsberg, H.S. Spatiotemporal modeling of dengue fever risk in Puerto Rico. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Mendonça, F.d.A. Past, present, and future vulnerability to dengue in Jamaica: A spatial analysis of monthly variations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultó, P.L.O.; Rodríguez, A.P.; Valencia, A.R.; Vega, N.L.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Carrera, A.P. Assessment of human health vulnerability to climate variability and change in Cuba. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.C. Geographical distribution of the association between El Niño South Oscillation and dengue fever in the Americas: A continental analysis using geographical information system-based techniques. Geospat. Health 2014, 9, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, K.O.; Samuels, T.A.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, R.; Vapalahti, O.; Sironen, T.; Gittens-St Hilaire, M. Serological Evidence of Human Orthohantavirus Infections in Barbados, 2008 to 2016. Pathogens 2021, 10, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.M.; Blair, P.J.; Carroll, D.S.; Mills, J.N.; Gianella, A.; Iihoshi, N.; Briggiler, A.M.; Felices, V.; Salazar, M.; Olson, J.G. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Santa Cruz, Bolivia: Outbreak investigation and antibody prevalence study. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayard, V.; Kitsutani, P.T.; Barria, E.O.; Ruedas, L.A.; Tinnin, D.S.; Muñoz, C.; De Mosca, I.B.; Guerrero, G.; Kant, R.; Garcia, A. Outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, Los Santos, Panama, 1999–2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Bryan, R.T.; Mills, J.N.; Palma, R.E.; Vera, I.; De Velasquez, F.; Baez, E.; Schmidt, W.E.; Figueroa, R.E.; Peters, C.J. An outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in western Paraguay. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997, 57, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafferata, M.L.; Bardach, A.; Rey-Ares, L.; Alcaraz, A.; Cormick, G.; Gibbons, L.; Romano, M.; Cesaroni, S.; Ruvinsky, S. Dengue epidemiology and burden of disease in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Value Health Reg. Issues 2013, 2, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiwanitkit, V. An observation on correlation between rainfall and the prevalence of clinical cases of dengue in Thailand. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2006, 43, 73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sumi, A.; Telan, E.; Chagan-Yasutan, H.; Piolo, M.; Hattori, T.; Kobayashi, N. Effect of temperature, relative humidity and rainfall on dengue fever and leptospirosis infections in Manila, the Philippines. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.D.; Santos, A.M.d.; Corrêa, R.d.G.C.F.; Caldas, A.d.J.M. Temporal relationship between rainfall, temperature and occurrence of dengue cases in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2016, 21, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedum, C.M.; Seidahmed, O.M.; Eltahir, E.A.; Markuzon, N. Statistical modeling of the effect of rainfall flushing on dengue transmission in Singapore. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbach, P.J. The Influence of El Nino-Southern Oscillation and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation on Caribbean Tropical Cyclone Activity. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, D.A.; Ault, T.R.; Carrillo, C.M.; Fasullo, J.T.; Li, X.L.; Evans, C.P.; Alessi, M.J.; Mahowald, N.M. Dynamical Characteristics of Drought in the Caribbean from Observations and Simulations. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 10773–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, D.; Lowe, R.; Stewart-Ibarra, A.; Ballester, J.; Koopman, S.J.; Rodó, X. Sensitivity of large dengue epidemics in Ecuador to long-lead predictions of El Niño. Clim. Serv. 2019, 15, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, T.; Lin, H.; Zhu, G.; Zeng, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Song, T.; Deng, A.; Zhang, M. Weather variables and the El Nino Southern Oscillation may drive the epidemics of dengue in Guangdong Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damtew, Y.T.; Tong, M.; Varghese, B.M.; Anikeeva, O.; Hansen, A.; Dear, K.; Zhang, Y.; Morgan, G.; Driscoll, T.; Capon, T. Effects of high temperatures and heatwaves on dengue fever: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pliego, E.P.; Velázquez-Castro, J.; Collar, A.F. Seasonality on the life cycle of Aedes aegypti mosquito and its statistical relation with dengue outbreaks. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 50, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.E.; Dolin, R.; Blaser, M.J. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfelder, M.; Koppe, C.; Pfafferott, J.; Matzarakis, A. Effects of ventilation behaviour on indoor heat load based on test reference years. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, O.P.; Cardoso, B.F.; Ribeiro, A.L.M.; Santos, F.A.L.d.; Slhessarenko, R.D. Mayaro virus and dengue virus 1 and 4 natural infection in culicids from Cuiabá, state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Memórias Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2016, 111, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.; Barrera, R.; Lewis, M.; Kluchinsky, T.; Claborn, D. Septic tanks as larval habitats for the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus in Playa-Playita, Puerto Rico. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2010, 24, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneson, A.; Beltrán-Ayala, E.; Borbor-Cordova, M.J.; Polhemus, M.E.; Ryan, S.J.; Endy, T.P.; Stewart-Ibarra, A.M. Social-ecological factors and preventive actions decrease the risk of dengue infection at the household-level: Results from a prospective dengue surveillance study in Machala, Ecuador. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matysiak, A.; Roess, A. Interrelationship between climatic, ecologic, social, and cultural determinants affecting dengue emergence and transmission in Puerto Rico and their implications for Zika response. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 2017, 8947067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabali, M.; Hernandez, L.M.; Arauz, M.J.; Villar, L.A.; Ridde, V. Why are people with dengue dying? A scoping review of determinants for dengue mortality. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allicock, O.M.; Sahadeo, N.; Lemey, P.; Auguste, A.J.; Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A.; Carrington, C.V. Determinants of dengue virus dispersal in the Americas. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, R.; Amador, M.; Diaz, A.; Smith, J.; Munoz-Jordan, J.; Rosario, Y. Unusual productivity of Aedes aegypti in septic tanks and its implications for dengue control. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2008, 22, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutikanga, H.E.; Sharma, S.; Vairavamoorthy, K. Water loss management in developing countries: Challenges and prospec. J. -Am. Water Work. Assoc. 2009, 101, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystosik, A.; Njoroge, G.; Odhiambo, L.; Forsyth, J.E.; Mutuku, F.; LaBeaud, A.D. Solid wastes provide breeding sites, burrows, and food for biological disease vectors, and urban zoonotic reservoirs: A call to action for solutions-based research. Front. Public Health 2020, 7, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, J.; Bhattacharya, N.; Bloch, R. The role of solid waste management as a response to urban flood risk in developing countries, a case study analysis. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 159, 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Huits, R.; Angelo, K.M.; Amatya, B.; Barkati, S.; Barnett, E.D.; Bottieau, E.; Emetulu, H.; Epelboin, L.; Eperon, G.; Medebb, L. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes Among Travelers With Severe Dengue: A GeoSentinel Analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Salmon, E.; Hill, V.; Paul, L.M.; Koch, R.T.; Breban, M.I.; Chaguza, C.; Sodeinde, A.; Warren, J.L.; Bunch, S.; Cano, N. Travel surveillance uncovers dengue virus dynamics and introductions in the Caribbean. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.K.; Paulos, A.H.; Zulli, A.; Duong, D.; Shelden, B.; White, B.J.; Boehm, A.B. Wastewater detection of emerging arbovirus infections: Case study of Dengue in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2023, 11, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan-Hernandez, L.; Van Oost, C.; Boehm, A.B. Solid–liquid partitioning of dengue, West Nile, Zika, hepatitis A, influenza A, and SARS-CoV-2 viruses in wastewater from across the USA. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024; advance article. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.C.C.; Tay, M.; Hapuarachchi, H.C.; Lee, B.; Yeo, G.; Maliki, D.; Lee, W.; Suhaimi, N.-A.M.; Chio, K.; Tan, W.C.H. Case report: Zika surveillance complemented with wastewater and mosquito testing. eBioMedicine 2024, 101, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.-W.; Chen, T.-Y.; Wang, S.-T.; Hou, T.-Y.; Wang, S.-W.; Young, K.-C. Establishment of quantitative and recovery method for detection of dengue virus in wastewater with noncognate spike control. J. Virol. Methods 2023, 314, 114687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, S.; Ortega-Villa, A.M.; Powers, J.H., III; León, H.A.R.; Sosa, S.C.; Hernández, E.R.; Cancino, J.G.N.; Nason, M.; Lumbard, K.; Sepulveda, J. Patterns of signs, symptoms, and laboratory values associated with Zika, dengue, and undefined acute illnesses in a dengue endemic region: Secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study in southern Mexico. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | People with acute DENV infection or DF/NSD/SD/DHF/DSS | Only mosquito DENV infections |

| Exposure | At least one climate factor | No climate factors |

| Comparators | N/A | |

| Outcomes | Dengue case/infection/risk/incidence | Mosquito density/distribution |

| Study design | Observational, epidemiological, retrospective, predictive modeling study design | Prospective study design |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Douglas, K.O.; Payne, K.; Sabino-Santos, G.; Chami, P.; Lorde, T. The Impact of Climate on Human Dengue Infections in the Caribbean. Pathogens 2024, 13, 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13090756

Douglas KO, Payne K, Sabino-Santos G, Chami P, Lorde T. The Impact of Climate on Human Dengue Infections in the Caribbean. Pathogens. 2024; 13(9):756. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13090756

Chicago/Turabian StyleDouglas, Kirk Osmond, Karl Payne, Gilberto Sabino-Santos, Peter Chami, and Troy Lorde. 2024. "The Impact of Climate on Human Dengue Infections in the Caribbean" Pathogens 13, no. 9: 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13090756

APA StyleDouglas, K. O., Payne, K., Sabino-Santos, G., Chami, P., & Lorde, T. (2024). The Impact of Climate on Human Dengue Infections in the Caribbean. Pathogens, 13(9), 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13090756