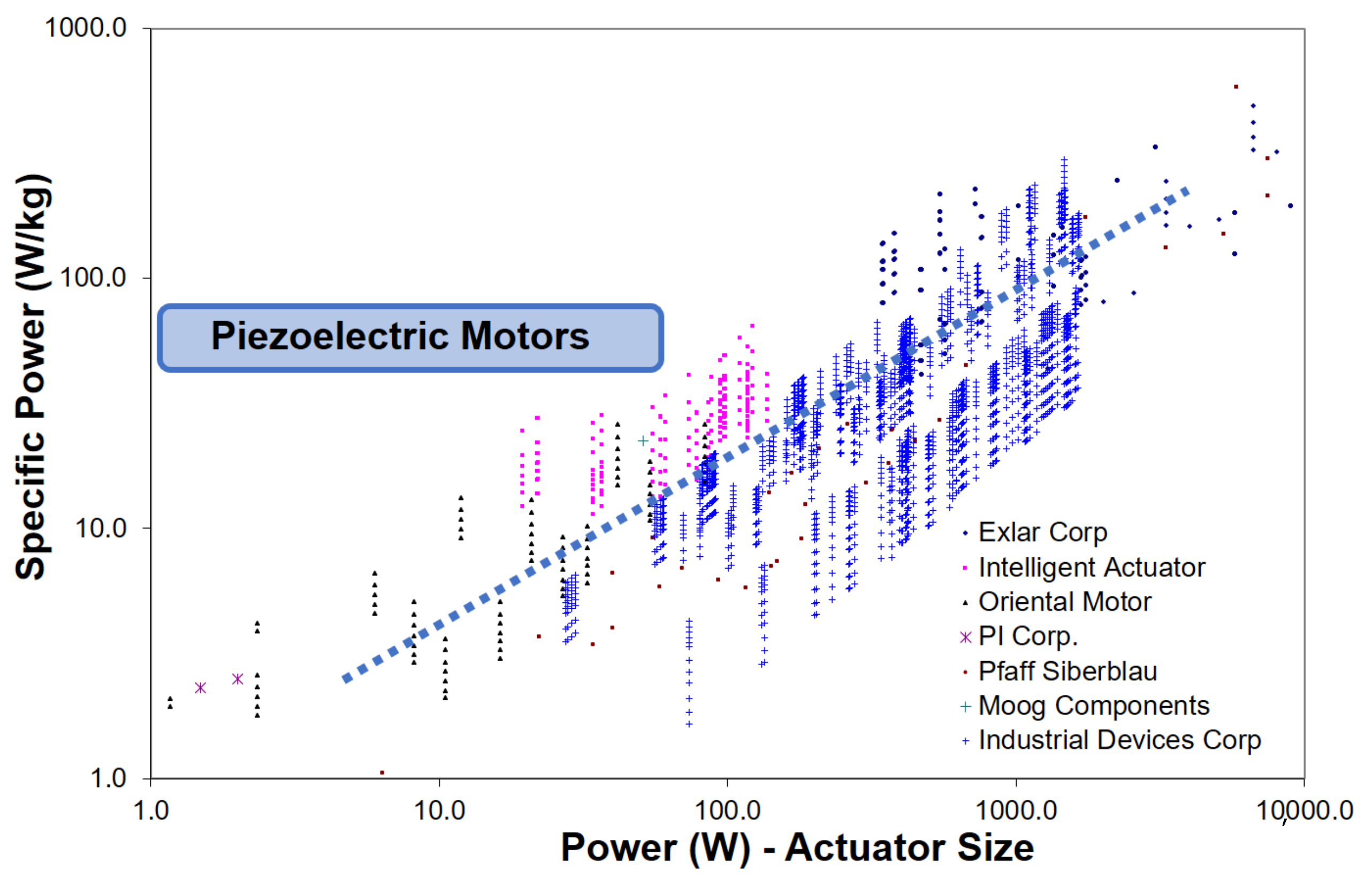

Figure 1.

Comparison of the specific power with respect to the power [

1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the specific power with respect to the power [

1].

Figure 2.

Statistics and future estimation of publications on piezoelectric energy harvesting.

Figure 2.

Statistics and future estimation of publications on piezoelectric energy harvesting.

Figure 3.

Strategic map of piezoelectric energy harvesting design aspects, modeling approaches, and applications.

Figure 3.

Strategic map of piezoelectric energy harvesting design aspects, modeling approaches, and applications.

Figure 4.

Piezoelectric coefficient range for some piezoelectric materials [

17].

Figure 4.

Piezoelectric coefficient range for some piezoelectric materials [

17].

Figure 5.

Three major phases associated with piezoelectric energy harvesting [

28].

Figure 5.

Three major phases associated with piezoelectric energy harvesting [

28].

Figure 6.

Comparison of the energy density for the three types of mechanical-to-electrical energy converters [

29].

Figure 6.

Comparison of the energy density for the three types of mechanical-to-electrical energy converters [

29].

Figure 7.

Unimorph structure of a piezoelectric energy harvester that has one piezo-layer and a proof mass [

39].

Figure 7.

Unimorph structure of a piezoelectric energy harvester that has one piezo-layer and a proof mass [

39].

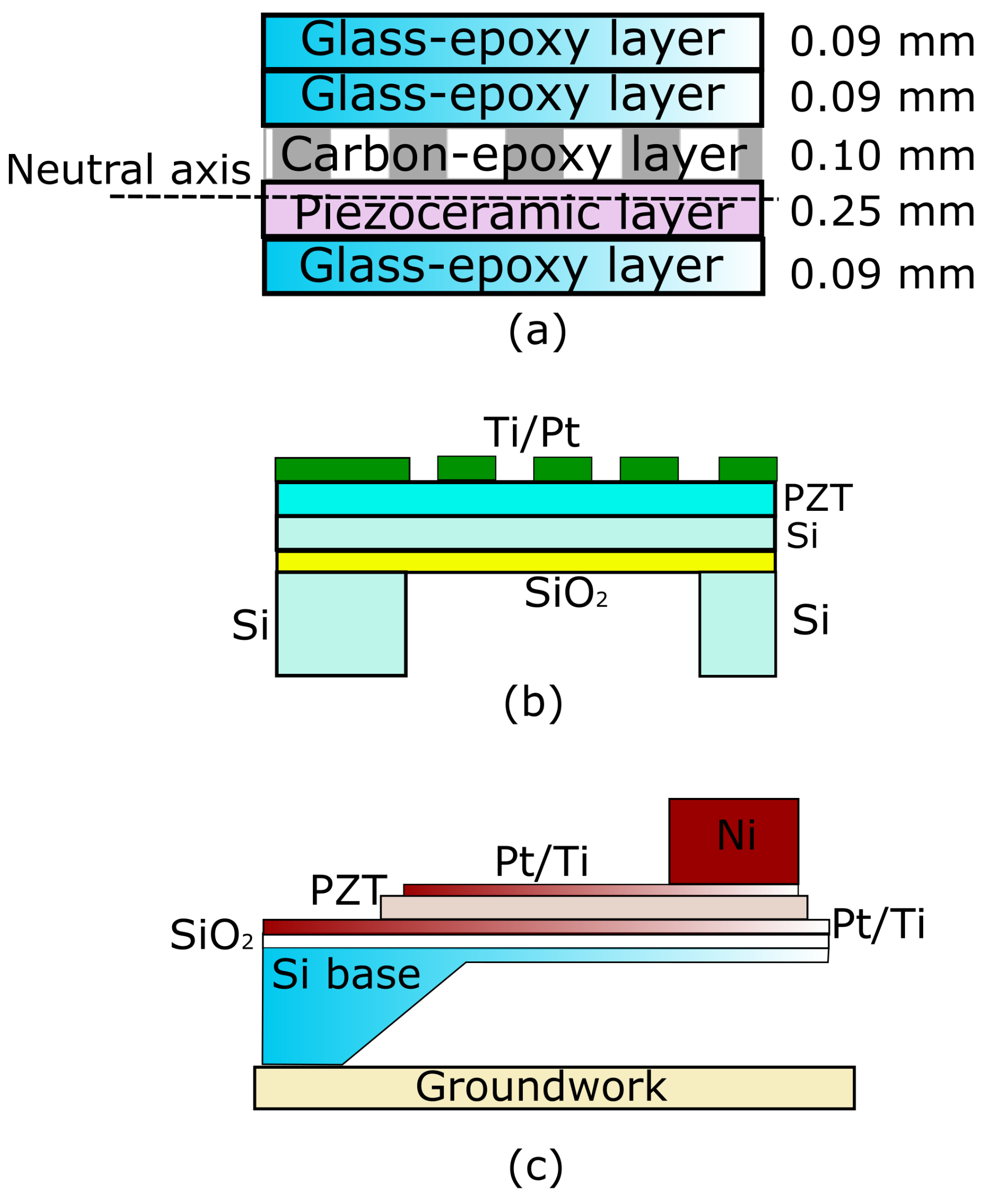

Figure 8.

(

a) Geometry and position of the neutral axis of piezocomposite composed of layers of carbon/epoxy, PZT ceramic, and glass/epoxy [

57]; (

b) a MEMS-based piezo-generator in 3-3 mode [

56]; (

c) schematic diagram of cross sectional view of a fabricated vibration-based micro power generator [

58].

Figure 8.

(

a) Geometry and position of the neutral axis of piezocomposite composed of layers of carbon/epoxy, PZT ceramic, and glass/epoxy [

57]; (

b) a MEMS-based piezo-generator in 3-3 mode [

56]; (

c) schematic diagram of cross sectional view of a fabricated vibration-based micro power generator [

58].

Figure 9.

Available sources of energy from organs of the human body. The data numbered 1–4 were obtained from [

9] and those numbered 4–13 from [

67]. The results are illustrated on Reza Abbasi’s “Prince Muhammad-Beik” drawing (1620, public domain).

Figure 9.

Available sources of energy from organs of the human body. The data numbered 1–4 were obtained from [

9] and those numbered 4–13 from [

67]. The results are illustrated on Reza Abbasi’s “Prince Muhammad-Beik” drawing (1620, public domain).

Figure 10.

Different classes of energy harvesting categories from flow-induced vibrations [

70].

Figure 10.

Different classes of energy harvesting categories from flow-induced vibrations [

70].

Table 1.

Overall evaluation of review papers written about non-focused topics on piezoelectric energy harvesting. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Numbers in brackets are scores for each item. Conclusions: 1: efficiency/performance improvement, 2: frequency tuning, 3: safety issues, 4: costs, hybrid harvesters, 5: non-linear models, 6: battery replacement, 7: miniaturization, 8: steady operation, 9: more efficient materials. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: paying attention to the range of output power. Sub-categories: 1: microscale, 2: electrostatic, 3: magnetic induction, 4: electromagnetic radiation, 5: thermal energy, 6: circuit, 7: wearable device, 8: ambient fluid flow, 9: sensors, 10: material, 11: human-related, 12: vibration, 13: hybrid device, 14: modelling, 15: road and shoe, 16: fluids, 17: animal-related.

Table 1.

Overall evaluation of review papers written about non-focused topics on piezoelectric energy harvesting. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Numbers in brackets are scores for each item. Conclusions: 1: efficiency/performance improvement, 2: frequency tuning, 3: safety issues, 4: costs, hybrid harvesters, 5: non-linear models, 6: battery replacement, 7: miniaturization, 8: steady operation, 9: more efficient materials. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: paying attention to the range of output power. Sub-categories: 1: microscale, 2: electrostatic, 3: magnetic induction, 4: electromagnetic radiation, 5: thermal energy, 6: circuit, 7: wearable device, 8: ambient fluid flow, 9: sensors, 10: material, 11: human-related, 12: vibration, 13: hybrid device, 14: modelling, 15: road and shoe, 16: fluids, 17: animal-related.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 6 (0.67) | microW to milliW (0) | 474 | 1, 2, 3, 4 (2.00) | 1, 6, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17 (0.47) | Safaei et al. [4] | B | High-temperature devices, metamaterials |

| 5 (0.56) | 375 microW (1) | 14 | 2, 4 (1.0) | 11, 12, 14 (0.18) | Taware and Deshmukh [6] | C | - |

| 5 (0.56) | microW (0) | 90 | 1, 3, 4 (1.5) | 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 (0.35) | Anton and Sodani [5] | C | - |

| 6 (0.67) | - (0) | 70 | 1, 2, 4 (1.5) | 10, 14 (0.12) | Sharma and Baredar [7] | C | Depolarization, sudden breaking of piezo layer due to high brittleness |

| 4 (0.44) | 100 microW (1) | 33 | 4 (0.50) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (0.35) | Mateu and Moll [8] | C | A discussion on power consumption of microelectronic devices |

| 4 (0.44) | - (0) | 153 | 1, 2, 4 (1.5) | 6, 10, 11, 14 (0.24) | Calio et al. [9] | C | Optimal shapes, buckling |

| 3 (0.33) | 1.3 milliW(1) | 16 | 4 (0.50) | - (0) | Sun et al. [10] | D | Comparison with energy from wind, solar, geothermal, coal, oil, and gas |

| 3 (0.33) | microW to milliW (0) | 54 | 1, 4 (1.0) | 2, 11, 12, 13 (0.24) | Khaligh et al. [11] | D | - |

| 1 (0.11) | microW to milliW (0) | 95 | 4 (0.5) | 10, 11, 12, 14, 15 (0.29) | Batra et al. [12] | E | - |

| 1 (0.11) | - (0) | 13 | - (0) | 10, 14, 15 (0.18) | Sharma et al. [13] | E | Historical points |

Table 2.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on materials in piezoelectric energy harvesting. The numbers in brackets denote non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: comparison of piezoelectric materials in terms of their important properties, 2: cost of piezoelectric materials, 3: selection strategies for piezoelectric materials, 4: increasing lifetime, endurance, size reduction, energy density, biocompatibility and manufacturability, 5: disadvantages and advantages of different types of piezo-materials, 6: the need for accurate modelling of piezoelectric materials; Merits: 1: piezoelectric coefficients, 2: coupling factors, 3: manufacturability, 4: mechanical strength, 5: guidelines for material selection, 6: paying attention to the range of output power or energy density, 7: stiffness, 8: quality factor; Sub-categories: 1: piezoelectric micro/macro fibers, 2: polymer nanofibers, 3: ceramic nanofibers, 4: piezoelectric nanowires, 5: micro-/nanofibers/wires composites, 6: piezoelectric polymers (PVDF, Pu, P(VDF-TrFE), cellular PP), 7: piezoelectric ceramics (PZT, PMM-PT, PMN-PZT …), 8: piezoelectric single crystals (Quartz …), 9: piezoelectric foams (PDMS piezoelectric, PET/EVA/PET piezoelectret, FEP piezoelectric), 10: piezoelectric powders, 11: piezoelectric composites (PVDF with nanofillers, non-piezoelectric polymer with BaTiO3), 12: bio materials.

Table 2.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on materials in piezoelectric energy harvesting. The numbers in brackets denote non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: comparison of piezoelectric materials in terms of their important properties, 2: cost of piezoelectric materials, 3: selection strategies for piezoelectric materials, 4: increasing lifetime, endurance, size reduction, energy density, biocompatibility and manufacturability, 5: disadvantages and advantages of different types of piezo-materials, 6: the need for accurate modelling of piezoelectric materials; Merits: 1: piezoelectric coefficients, 2: coupling factors, 3: manufacturability, 4: mechanical strength, 5: guidelines for material selection, 6: paying attention to the range of output power or energy density, 7: stiffness, 8: quality factor; Sub-categories: 1: piezoelectric micro/macro fibers, 2: polymer nanofibers, 3: ceramic nanofibers, 4: piezoelectric nanowires, 5: micro-/nanofibers/wires composites, 6: piezoelectric polymers (PVDF, Pu, P(VDF-TrFE), cellular PP), 7: piezoelectric ceramics (PZT, PMM-PT, PMN-PZT …), 8: piezoelectric single crystals (Quartz …), 9: piezoelectric foams (PDMS piezoelectric, PET/EVA/PET piezoelectret, FEP piezoelectric), 10: piezoelectric powders, 11: piezoelectric composites (PVDF with nanofillers, non-piezoelectric polymer with BaTiO3), 12: bio materials.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 4 (0.67) | microW to mW (1) | 120 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 (1.50) | 6, 7, 8, 11 (0.33) | Li et al. [16] | B | 1. the current state of research on piezoelectric energy harvesting devices for low-frequency (0–100 Hz) applications and the methods that have been developed to improve the power outputs of the piezoelectric energy harvesters are reviewed. 2. The selection of the appropriate piezoelectric material for a specific application and methods to optimize the design of the piezoelectric energy harvester are discussed. |

| 4 (0.67) | microW to mW (1) | 175 | 1, 3, 4, 6 (1) | 1, 6, 7, 8, 11 (0.42) | Narita and Fox [17] | B | 1. The harvested power of PZT-based PEHs with different structures are reported. 2. The recent advances in the field of PEHs made of PVDF, and polymer based composite piezoelectrics are reported, comparing the output power of some piezoelectric energy harvesters. |

| 3 (0.50) | microW (1) | 24 | 2, 6, 9 (0.75) | 6, 8 (0.17) | Lefeuvre [25] | C | 1. Figures of merit for energy conversion efficiency. 2. Figure of merit for piezoelectric materials. 3. Comparison of one-, two-, and three-stage electric power interfaces |

| 3 (0.50) | microW to nW (0) | 474 | 1, 3, 6, 7 (1.00) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11 (0.75) | Safaei et al. [4] | C | Recent advances in the field of piezoelectric materials are reported. Review of some novel piezoelectric materials such as piezoelectric foam and high-temperature materials |

| 4 (0.67) | microW (0) | 446 | 1, 3, 5, 6 (1) | 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 (0.50) | Liu et al. [21] | C | 1. Report on recent progress in the field of piezoelectric materials. 2. Description of fabrication techniques for many piezoelectric materials in energy harvesting applications. 3. Explanation of the main frequency bandwidth broadening techniques. 4. Classification of piezoelectric materials, fabrication techniques, and frequency bandwidth broadening techniques. |

| 4 (0.67) | microW (0) | 173 | 3, 4, 5, 6 (1) | 1- 2- 3- 4- 5 (0.42) | Zaarour et al. [18] | C | 1. Manufacturing methods for nanofibers and wires. 2. Contains mention of output voltages and currents of nano-/micro-materials. 3. Comparison of nano-/micro-materials based on maximum voltage and currant and active area. |

| 2 (0.33) | mW (0) | 50 | 1, 4, 6, 7, 8 (1.25) | 6, 7 (0.17) | Yoan et al. [19] | D | 1. Introduction of electrostrictive and dielectric electro-active polymers. 2. Performance comparison of PZT, PVDF, and DEAPs and electrostrictive polymers. Description of the industrial challenges for dielectric electro-active polymers. |

| 3 (0.50) | microW(0) | 158 | 1, 2, 3 (0.75) | 6, 7, 8, 11 (0.33) | Mishra et al. [20] | D | The article basically aims at exploring the basic theory behind the piezoelectric behavior of polymeric and composite systems and comparing the important types of piezoelectric polymers and composites. The article describes the piezoelectric properties of many piezo-polymers and polymer composites. |

| 3 (0.50) | microW (0) | 216 | 1, 2, 9 (0.75) | 6, 7, 8 (0.25) | Bowen et al. [22] | D | Reviews some resent topics such as piezoelectric light harvesting, pyroelectric based harvesting, and nanoscale pyroelectric systems |

| 2 (0.33) | microW to mW (0) | 16 | 1, 2, 5, 8 (1) | 7 (0.08) | Mukherjee and Datta [26] | D | 1. Effect of load resistance on the output power of PEHs. 2. Selection criteria for piezoelectric ceramics |

Table 3.

Overall evaluation of review papers on the design of piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement and optimization of PHEs; 2: widening the frequency bandwidth and frequency tuning of PHEs; 3: increasing life time and endurance of PHEs and their size reduction, packaging and manufacturability; 4: importance of electric interface circuits and storage circuits; 5: material selection strategy and material properties improvement: 6: necessity of standardizing the characterization methods of PHEs. Merits: 1: reporting the output power of PHEs, 2: coupling factors and operational mode, 3: including mathematical models, 4: matching the resonance frequency of PHEs with motivating frequencies, 5: paying attention to the energy conversion efficiencies. Sub-categories: mentioned in the text.

Table 3.

Overall evaluation of review papers on the design of piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement and optimization of PHEs; 2: widening the frequency bandwidth and frequency tuning of PHEs; 3: increasing life time and endurance of PHEs and their size reduction, packaging and manufacturability; 4: importance of electric interface circuits and storage circuits; 5: material selection strategy and material properties improvement: 6: necessity of standardizing the characterization methods of PHEs. Merits: 1: reporting the output power of PHEs, 2: coupling factors and operational mode, 3: including mathematical models, 4: matching the resonance frequency of PHEs with motivating frequencies, 5: paying attention to the energy conversion efficiencies. Sub-categories: mentioned in the text.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 4 (0.67) | mW (1) | 35 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2) | 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20 (0.50) | Uchino [28] | A | 1: describing the historical background of piezoelectric energy harvesting, 2: commenting on several misconceptions by current researchers, 3: step-by-step detailed energy flow analysis in energy harvesting systems, 4: describing the key to dramatic enhancement in the efficiency, 5: important comments on the useful/non-useful output power level for the harvesters |

| 5 (0.83) | mW (1) | 75 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2) | 9, 10, 11, 13, 19 (0.25) | Priya [29] | A | Describing the material selection criteria in on- and off-resonance conditions; describing the factors which affect the conversion efficiency of PHEs; the introduction of some low-profile PHEs for the realization of self-powered sensor nodes |

| 4 (0.67) | microW to mW (1) | 338 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2) | 4, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 (0.40) | Yang et al. [30] | A | Analysis of different designs, nonlinear methods, optimization techniques, and materials for increasing performance. Introduction of a set of metrics for the end users of PHEs for the comparison of the performance of PHEs |

| 4 (0.67) | microW to mW (1) | 120 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2) | 1, 5, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19 (0.40) | Li et al. [16] | A | Commenting on the biggest challenges for PHEs, describing the most important limitations of piezoelectric materials |

| 4 (0.67) | microW to mW (1) | 135 | 1, 2, 4, 5 (1.6) | 4, 7, 9, 12, 14, 20 (0.30) | Talib et al. [33] | B | The authors commented that the anticipated performance of a piezoelectric harvester can be attained by achieving a trade-off between output power and bandwidth. |

| 4 (0.67) | microW to mW (1) | 66 | 1, 3, 4 (1.2) | 1, 2, 13 (0.15) | Ibrahim and Vahied. [32] | B | Classifying, reviewing, and comparing different manual and autonomous tuning methods; meeting the challenge of energy consumption by means of self-tuning structures |

| 3 (0.50) | microW to mW (0) | 446 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2) | 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20 (0.50) | Liu et al. [21] | B | Various key aspects to improve the overall performance of a PEH device are discussed. Classification of performance improvement approaches. |

| 2 (0.33) | mW (1) | 105 | 1, 3, 4 (1.2) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 (0.35) | Yildirim et al. [31] | C | New classification of performance enhancement techniques. Comparison of many performance enhancement techniques. |

| 2 (0.33) | microW (0) | 149 | 1, 3, 4, 5 (1.6) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 (0.40) | Maamer et al. [27] | C | Proposal of a new generic categorization, using an approach based on the improvement aspects of the harvester, which includes techniques for widening the operating frequency, conceiving a non-resonant system and multidirectional harvester. Evaluating the applicability of the performance improvement techniques under different conditions and their compatibility with MEMS technology. |

Table 4.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on power interfaces in piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement strategies, 2: challenges and future perspectives, 3: comparision of electric interface circuits, 4: electric impedance matching, 5: implementation easiness and load independency of interface circuits. Merits: 1: Energy flow analysis of PHEs, 2: practical implementation of electronic interfaces, 3: including mathematical models, 4: paying attention to electrical impedance matching, 5: paying attention to the energy consumption of electric interfaces, 6: analysis of energy conversion efficiency. Sub-categories: mentioned in the text.

Table 4.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on power interfaces in piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement strategies, 2: challenges and future perspectives, 3: comparision of electric interface circuits, 4: electric impedance matching, 5: implementation easiness and load independency of interface circuits. Merits: 1: Energy flow analysis of PHEs, 2: practical implementation of electronic interfaces, 3: including mathematical models, 4: paying attention to electrical impedance matching, 5: paying attention to the energy consumption of electric interfaces, 6: analysis of energy conversion efficiency. Sub-categories: mentioned in the text.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 4 (0.80) | mW (1) | 35 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (2) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 18, 21 (0.41) | Uchino [28] | A | The authors report on the minimum acceptable output power for harvesters, energy flow analysis for a cymbal-type transducer, and a description of the electric impedance matching technique |

| 5 (1) | microW (1) | 113 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (1.67) | 2, 4, 5, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21 (0.41) | Szarka et al. [35] | A | Overview of power management techniques that aim to maximize the extracted power of PHEs. Description of the requirements for power electronics, reviewing various power conditioning techniques and comparing them in terms of complexity, efficiency, quiescent power consumption, and startup behavior |

| 3 (0.60) | - (0) | 109 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (2) | 8 to 17 (0.45) | Brenes et al. [34] | B | Comparison of the conditions for electric tuning techniques used to maximize the power flow from an external vibration source to an electrical load description of necessary conditions for maximum power point tracking (MPPT) |

| 3 (0.60) | - (0) | 113 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (1.67) | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 15, 16, 21, 22 (0.41) | Francesco et al. [36] | C | 1: Almost all the rectification techniques employed in PEH systems are discussed and comparedm emphasizing the advantages and disadvantages of each approach. 2: Introducing seven criteria used to evaluate the performance of a harvesting interface |

| 2 (0.40) | - (0) | 64 | 2, 3, 5, 6 (1.33) | 6, 7, 20 (0.14) | Guyomar and Lallart [37] | D | 1: review of nonlinear electronic interfaces for energy harvesting from mechanical vibrations; 2: comparative analysis of various switching techniques in terms of efficiency, performance under several excitation conditions, and complexity of implementation |

Table 5.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on MEMS piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Suitable materials for MEMS/NEMS piezo harvesters; 2: synthesis and fabrication of MEMS/NEMS materials and structures; 3: hybrid materials and structures; 4: efficiency and performance of MEMS/NEMS harvesters and their improvement; 5: necessity of frequency bandwidth broadening and optimizations; 6: increasing life time, endurance, stability, and embedding abilities; 7: cost reduction, manufacturability and CMOS compatibility; 8: improvement of material properties and development of new architectures; 9: electronic interface circuits; 10: characterization of MEMS/NEMS devices and size effect. Merits: 1: Reports the output power or power density of MEMS/NEMS PHEs; 2: coupling factors and operational modes; 3: describes the fabrication techniques; 4: matching of the resonance frequency of PHEs with motivating frequencies, 5: pays attention to the minimum required output power, 6: CMOS compatibility, 7: energy flow analysis. Sub-categories: mentioned in the text.

Table 5.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on MEMS piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Suitable materials for MEMS/NEMS piezo harvesters; 2: synthesis and fabrication of MEMS/NEMS materials and structures; 3: hybrid materials and structures; 4: efficiency and performance of MEMS/NEMS harvesters and their improvement; 5: necessity of frequency bandwidth broadening and optimizations; 6: increasing life time, endurance, stability, and embedding abilities; 7: cost reduction, manufacturability and CMOS compatibility; 8: improvement of material properties and development of new architectures; 9: electronic interface circuits; 10: characterization of MEMS/NEMS devices and size effect. Merits: 1: Reports the output power or power density of MEMS/NEMS PHEs; 2: coupling factors and operational modes; 3: describes the fabrication techniques; 4: matching of the resonance frequency of PHEs with motivating frequencies, 5: pays attention to the minimum required output power, 6: CMOS compatibility, 7: energy flow analysis. Sub-categories: mentioned in the text.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 8 (0.80) | microW (1) | 89 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 (2) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 18 (0.24) | Kim et al. [39] | A | Describes figures of merits for MEMS PHEs, mentions the key attributes for MEMS PHEs, describing minimum acceptable power density for MEMS PHEs |

| 7 (0.70) | microW (1) | 140 | 1, 3, 4, 5 (1.14) | 1, 4, 23, 25 (0.16) | Khan [50] | B | 1: The review covers the available material forms and applications of piezoelectric thin films. 2: The electromechanical properties and performances of piezoelectric films are compared and their suitability for particular applications is reported. 3: Control over the growth of piezoelectric thin films and lead-free compositions of thin films can lead to good environmental stability and responses, coupled with higher piezoelectric coupling coefficients. |

| 5 (0.50) | microW to mW (1) | 74 | 1, 2, 4, 5 (1.14) | 6, 7, 8, 10, 23, 24 (0.24) | Dutoit et al. [2] | C | Comments on the necessary information for comparing different PHEs. Points out the differences between dominant damping components at the micro- vs. macro-scale. Develops a fully coupled electromechanical model for analyzing the response of PHEs with a cantilever configuration. |

| 5 (0.50) | microW to mW (0) | 123 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (1.71) | 8, 13, 18, 19, 21 (0.20) | Toprak and Tigli [40] | C | 1: Notes that size-based classification provides a reliable and effective basis for the study of various piezoelectric energy harvesters. 2: Discusses the most prominent challenges in piezoelectric energy harvesting and the studies focusing on these challenges. |

| 6 (0.60) | microW to mW (0) | 145 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (1.71) | 4, 8, 11, 18, 21, 23 (0.24) | Todaro et al. [41] | C | 1: Reviews the current status of MEMS energy harvesters based on piezoelectric thin films. 2: The paper has highlighted approaches/strategies to face the two main challenges to be addressed for high-performance devices, namely, the generated power and frequency bandwidth. 3: Comparison of several MEMS energy harvesters’ performances. |

| 6 (0.6) | microW to mW (0) | 108 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (1.43) | 1, 5, 12, 13 (0.16) | Jing and Kar-Narayan [46] | C | 1: Discussion of the growth of nanomaterials, including nanowires of polymers of polyvinylidene fluoride and its co-polymers, nylon-11, and poly-lactic acid for scalable piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerator applications. 2: Discusses the design and performance of polymer-ceramic nanocomposite. |

| 4 (0.40) | microW to mW (0) | 115 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (1.43) | 7, 14, 15, 24 (0.16) | Beeby [43] | D | Provides a characterization and comparison of piezoelectric, electromagnetic, and electrostatic MEMS generators |

| 4 (0.40) | mW (0) | 34 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (1.43) | 12, 24 (0.08) | Salim et al. [44] | D | Elaborates on hybrid energy harvesters, reports on the literature on such harvesters for recent years with different architectures, models, and results, comparing the present hybrid PHEs in terms of output power. |

| 6 (0.60) | microW (0) | 95 | 1, 2, 3, 4 (1.14) | 1, 13, 22, 25 (0.16) | Briscoe and Dunn [42] | D | 1: This review summarizes the work to date on nanostructured piezoelectric energy harvesters. 2: The authors state that in order to satisfy the needs of real power delivery, devices need to maximize the rate of change of any strain delivered into a system in order to increase the polarization developed by the functional layers, and improve the coupling of the device to the environment. |

| 7 (0.70) | microW (0) | 78 | 1, 2, 3 (0.86) | 1, 13, 17, 18, 24, 25 (0.24) | Wang et al. [48] | D | The working mechanism, modeling, and structure design of piezoelectric nanogenerators are discussed. The integration of nanogenerators for high output power sources, the structural design for increasing the energy harvesting efficiency in different conditions, and the development of practicable integrated self-powered systems with improved stability and reliability are the critical issues in the field classification of nano generators based on their design and working modes. |

| 3 (0.30) | - (0) | 80 | 1, 2, 3, 4 (1.14) | 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 20, 25 (0.36) | Gosavi and Balpande [14] | D | Description of some of the synthesis and deposition techniques and performance parameters for MEMS PHEs |

| 3 (0.30) | - (0) | 75 | 1, 3, 4, 5 (1.14) | 1, 23, 25 (0.12) | Muralt et al. [49] | D | The article has reviewed the impact of composition, orientation, and microstructure on the piezoelectric properties of perovskite thin films. The author describes useful power levels for MEMS PHEs. |

| 5 (0.50) | microW (0) | 69 | 1, 2, 4 (0.86) | 1, 13, 18, 20, 24, 25 (0.24) | Wang [47] | D | 1: Theoretical calculations and experimental characterization methods for predicting or determining the piezoelectric potential output of NWs are reviewed. 2: Numerical calculation of the energy output from NW-based NGs. 3: Integration of a large number of ZnO NWs is demonstrated as an effective pathway for improving the output power. |

| 5 (0.50) | mW (0) | 112 | 1, 4, 5 (0.86) | 3, 16, 17, 18 (0.16) | Selvan and Ali [38] | D | The capabilities and efficiencies off our micro-power harvesting methods including thermoelectric, thermo-photovoltaic, piezoelectric, and microbial fuel cell renewable power generators are thoroughly reviewed and reported |

| 3 (0.30) | - (0) | 100 | 1, 3 (0.57) | 12, 13, 18, 25 (0.16) | Kumar and Kim [45] | D | 1: Description of the mechanism of power generation behavior of nanogenerators fabricated from ZnO nanostructures. 2: Describes an innovative and important hybrid approach based on ZnO nano-structures. |

Table 6.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on the modeling of piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Comparing the reviewed models; 2: the accuracy of the models and correction factors; 3: models constraints and limitations; 4: advantges and disadvantages of the models; 5: design consideration based on the modeling results. Merits: 1: Giving the mathematical background of the models; 2: considering the energy losses; 3: taking into account the resonance and off-resonance conditions; 4: efficiency modeling; 5: mentioning the constraints and limitations of the model; 6: mentioning the assumptions followed by the models; 7: comparison of the existing models. Sub-categories: 1: Energy conversion in PHEs with linear models; 2: energy conversion in PHEs with nonlinear models; 3: modeling efficiency and correction factors; 4: comparison of existing models for cantilever PHEs (SDOF models and distributed parameter modeling); 5: comparison of existing models for aeroelastic energy harvesting (models for flutter in airfoil sections, vortex-induced vibrations in circular cylinders, galloping in prismatic structures, VIV-/cylinder-based aeroelastic energy harvesters, galloping-based aeroelastic energy harvesters, wake galloping, SDOF models, Euler–Bernoulli distributed parameter model).

Table 6.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on the modeling of piezoelectric energy harvesters. The numbers in brackets denote the number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Comparing the reviewed models; 2: the accuracy of the models and correction factors; 3: models constraints and limitations; 4: advantges and disadvantages of the models; 5: design consideration based on the modeling results. Merits: 1: Giving the mathematical background of the models; 2: considering the energy losses; 3: taking into account the resonance and off-resonance conditions; 4: efficiency modeling; 5: mentioning the constraints and limitations of the model; 6: mentioning the assumptions followed by the models; 7: comparison of the existing models. Sub-categories: 1: Energy conversion in PHEs with linear models; 2: energy conversion in PHEs with nonlinear models; 3: modeling efficiency and correction factors; 4: comparison of existing models for cantilever PHEs (SDOF models and distributed parameter modeling); 5: comparison of existing models for aeroelastic energy harvesting (models for flutter in airfoil sections, vortex-induced vibrations in circular cylinders, galloping in prismatic structures, VIV-/cylinder-based aeroelastic energy harvesters, galloping-based aeroelastic energy harvesters, wake galloping, SDOF models, Euler–Bernoulli distributed parameter model).

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 5(1) | mW (0) | 21 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 (2) | 1, 3, 4 (0.60) | Erturk and Inman [51,52] | B | Issues of the correct formulation for piezoelectric coupling, correct physical modeling, use of low fidelity models, incorrect base motion |

| 4 (0.8) | mW (0) | 48 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 (1.71) | 1, 5 (0.40) | Zhao et al. [53] | C | Comparison of the performance of the modeling methods for GPEH, including the SDOF model, and single mode and multimode Euler–Bernoulli distributed parameter models. |

| 1 (0.25) | microW (0) | 204 | 1, 2, 4 (0.85) | 1, 2, 3, (0.60) | Wei and Jing [54] | D | 1: Review of the energy conversion efficiency of some of the conversion mechanisms; 2: description of several configuration design for PHEs such as cantilever structures, and uniform membrane structures. |

| 0(0) | mW (0) | 201 | 3, 5 (0.57) | 1, 2, 5 (0.60) | Abdelkefi [55] | D | Qualitative and quantitative comparisons between existing flow-induced vibrations energy harvesters, describing some of the limitations of existing models and recommending some improvement for future |

Table 7.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from vibration sources. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement, 2: frequency tuning, 3: safety issues, 4: costs, 5: hybrid harvesters, 6: non-linear models, 7: battery replacement, 8: miniaturization, 9: steady operation, 10: more efficient materials, 11: stochastic modeling. Merits: 1: Electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: Circuits, 2: type of materials, 3: modeling, 4: noise level, 5: wearable, 6: frequency range, 7: MEMS.

Table 7.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from vibration sources. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement, 2: frequency tuning, 3: safety issues, 4: costs, 5: hybrid harvesters, 6: non-linear models, 7: battery replacement, 8: miniaturization, 9: steady operation, 10: more efficient materials, 11: stochastic modeling. Merits: 1: Electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: Circuits, 2: type of materials, 3: modeling, 4: noise level, 5: wearable, 6: frequency range, 7: MEMS.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 6 (0.55) | 0.17 microW (1) | 35 | 2-4 (1.5) | 1, 3, 4, 5 (0.57) | Sodano et al. [56] | B | Insufficient output power |

| 3 (0.27) | microW to mW (0) | 93 | 1-4 (2.0) | 1, 2, 3, 5 (0.57) | Kim et al. [57] | C | Comparison with electrostatic and electromagnetic energy conversions |

| 6 (0.55) | microW to mW (0) | 145 | 1-4 (2.0) | 7 (0.14) | Siddique et al. [58] | C | Comparison with electromagnetic and electrostatic |

| 3 (0.27) | 60 microW (1) | 23 | 2, 4 (1.0) | 1, 7 (0.29) | Saadon and Sidek [59] | C | Inadequate output power |

| - (0.0) | 2.46 mW (1) | 56 | 3, 4 (1.0) | 1, 6 (0.29) | Harb [60] | C | From thermal sources, RF sources, CMOS devices, and power management sources |

| 7 (0.64) | - (0) | 50 | 2, 3 (1.0) | 6 (0.14) | Zhu et al. [61] | D | Focused on frequency tuning |

| 5 (0.46) | - (0) | 84 | 1, 2 (1.0) | 2, 3 (0.29) | Harne and Wang [62] | D | Focused on bistable systems, stochastic vibrations |

Table 8.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from biological applications. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement, 2: safety issues, 3: costs, 4: hybrid harvesters, 5: non-linear models, 6: battery replacement, 7: miniaturization, 8: steady operation, 9: efficient (flexible, stretchable, bio-compatible) materials, 10: self-powered, 11: wearability, 12: control systems. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: organ motion, 2: heel strike, 3: ankle, 4: Knee, 5: hip, 6: center of mass, 7: arms, 8: muscles, 9: cardiac/lung motion, 10: blood circulation, 11: heat emission, 12: drug delivery, 13: dental cases, 14: thin films, 15: artificial hair cell, 16: biosensors.

Table 8.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from biological applications. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement, 2: safety issues, 3: costs, 4: hybrid harvesters, 5: non-linear models, 6: battery replacement, 7: miniaturization, 8: steady operation, 9: efficient (flexible, stretchable, bio-compatible) materials, 10: self-powered, 11: wearability, 12: control systems. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: organ motion, 2: heel strike, 3: ankle, 4: Knee, 5: hip, 6: center of mass, 7: arms, 8: muscles, 9: cardiac/lung motion, 10: blood circulation, 11: heat emission, 12: drug delivery, 13: dental cases, 14: thin films, 15: artificial hair cell, 16: biosensors.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 5 (0.42) | 250 V, 8.7 microA (1) | 71 | 1, 3, 4 (1.5) | 1, 9, 14, 15 (0.25) | Hwang et al. [63] | B | Focused on thin films |

| 9 (0.75) | 11V, 283 microA (1) | 240 | 1, 4 (1.0) | 1, 8, 9, 10, 16 (0.31) | Ali et al. [64] | B | - |

| 8 (0.67) | 1 microF, 20 V, 50 s (1) | 235 | 1, 4 (1.0) | 1, 16 (0.13) | Surmenev et al. [65] | C | Lead-free polymer-based, size-dependent effects, insufficient output power of piezoelectric polymers and their copolymers |

| 7 (0.58) | 11 mWcm (1) | 107 | 1, 4 (1.0) | 8, 9, 10 (0.19) | Zheng et al. [66] | C | Comparison with triboelectric methods |

| 4 (0.33) | 2W (1) | 38 | 4 (0.50) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11 (0.50) | Riemer and Shapiro [67] | C | Comparison with electrical induction generators and electroactive polymers |

| 1 (0.08) | mW (0) | 29 | 4 (0.50) | 12, 13 (0.13) | Mhetre et al. [68] | D | - |

| 4 (0.33) | - (0) | 53 | 1 (0.50) | 1 (0.063) | Xin et al. [69] | E | Shoe-equipped geometry classification |

Table 9.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from fluids. The numbers in parentheses denote number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement, 2: frequency tuning, 3: safety issues, 4: costs, 5: hybrid harvesters, 6: non-linear models, 7: battery replacement, 8: miniaturization, 9: steady operation, 10: more efficient materials. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: water waves, 2: galloping, 3: fluttering, 4: buffeting, 5: modelling, 6: wind’s vortex street, 7: instabilities, 8: raindrop, 9: mechanical design.

Table 9.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from fluids. The numbers in parentheses denote number of non-general future lines. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement, 2: frequency tuning, 3: safety issues, 4: costs, 5: hybrid harvesters, 6: non-linear models, 7: battery replacement, 8: miniaturization, 9: steady operation, 10: more efficient materials. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: water waves, 2: galloping, 3: fluttering, 4: buffeting, 5: modelling, 6: wind’s vortex street, 7: instabilities, 8: raindrop, 9: mechanical design.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 9 (0.9) | >0.0289 mW (1) | 125 | 1, 2, 3, 4 (2.0) | 1, 2, 3, 4 (0.44) | Wang et al. [70] | A | Internet of things, machine learning tools |

| 4 (0.4) | 115 mW (1) | 62 | 1 2, 3, 4 (2.0) | 2, 3, 6, 7 (0.44) | Truitt and Mahmoodi [71] | B | Active control theory |

| 4 (0.4) | 116 microW/cm (1) | 96 | 1, 2, 4 (1.5) | 1, 9 (0.22) | Viet et al. [72] | B | - |

| 5 (0.5) | 440 microW/cm (1) | 96 | 2, 4 (1.0) | 3, 6, 9 (0.33) | McCarthy et al. [73] | C | Noise level, atmospheric boundary layer, fatigue life |

| 5 (0.5) | >1 microW (1) | 199 | 4 (0.50) | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7 (0.56) | Hamlehdar et al. [74] | C | Biomimetic design |

| 4 (0.4) | - (0) | 87 | 1, 3, 4 (1.5) | 8 (0.11) | Wong et al. [75] | C | Size effects |

| 5 (0.5) | nW to mW (0) | 256 | 1, 4 (1.0) | 2, 3, 6 (0.33) | Elahi et al. [76] | D | Human-based sources |

| 4 (0.4) | microW (0) | 73 | 4 (0.50) | 8 (0.11) | Chua et al. [77] | D | Circuit design, hydrophilic surface |

Table 10.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from waste energies. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement and optimization, 2: safety issues, 3: costs, 4: hybrid harvesters, 5: non-linear models, 6: battery replacement, 7: miniaturization, 8: steady operation, 9: efficient materials, 10: control systems. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: acoustic energy, 2: modelling, 3: road pavement, 4: railway, 5: bridge.

Table 10.

Overall evaluation of review papers written on piezoelectric energy harvesting from waste energies. “Cons.” stands for conclusions. Conclusions: 1: Efficiency/performance improvement and optimization, 2: safety issues, 3: costs, 4: hybrid harvesters, 5: non-linear models, 6: battery replacement, 7: miniaturization, 8: steady operation, 9: efficient materials, 10: control systems. Merits: 1: electromechanical coupling factor, 2: realistic resonance, 3: energy flow, 4: range of output. Sub-categories: 1: acoustic energy, 2: modelling, 3: road pavement, 4: railway, 5: bridge.

| # Cons. | Minimum Required Output | # Refs. | Merits | Sub-Categories | Ref. | Grade | Highlights |

|---|

| 4 (0.4) | 241 Wh/y (1) | 120 | 3, 4 (1.0) | 3, 5 (0.40) | Wang et al. [80] | C | Comparison with photovoltaic cell, solar collector, geothermal, thermoelectric, electromagnetic devices, fatigue failure and life-cycle |

| 4 (0.4) | 100 mW (1) | 65 | 3, 4 (1.0) | 2, 3 (0.40) | Guo and Lu [78] | C | Comparison with thermoelectrics |

| 4 (0.4) | 10–100 W (1) | 34 | 3, 4 (1.0) | 4 (0.20) | Duarte and Ferreira [79] | C | Comparison with electromagnetic devices, TRL level presented |

| 3 (0.3) | - (0) | 80 | 2, 4 (1.0) | 1, 2 (0.40) | Pillai and Deenadayalan [81] | D | Comparison with thermo-acoustics |

| 2 (0.2) | - (0) | 54 | 2, 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.20) | Khan and Izhar [82] | D | Comparison with electromagnetics |

| 2 (0.2) | - (0) | 97 | 4 (0.50) | 3 (0.20) | Duarte and Ferreira [83] | E | Comparison with solar, thermoelectric, and electromagnetic devices |

Table 11.

Statistics for review papers published on different topics related to piezoelectric energy harvesting. The numbers in brackets demonstrate the number of funded review papers in each field.

Table 11.

Statistics for review papers published on different topics related to piezoelectric energy harvesting. The numbers in brackets demonstrate the number of funded review papers in each field.

| | Topic | #Reviews | Period | # Reviews per Year | Non-University Research Fund Sources |

|---|

| 1 | General | 8 (4) | 2005–2019 | 0.53 | National Science Foundation (USA), National Natural Science Foundation (China), Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology and the Regional European Development Funds (European Union), NanoBioTouch European project/Telecom Italia/Scuola Superiore SantAnna (Italy). |

| 2 | Design | 15 (5) | 2005–2020 | 0.94 | Texas ARP (USA), U.S. Department of Energy Wind and Water Power Technologies Office (USA), Ministry of Higher Education (Malaysia), Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (Canada), National Natural Science Foundation (China)/EU Erasmus+ project/Bevilgning |

| 3 | Material | 11 (7) | 2009–2019 | 1.00 | M/s Bharat Electronics Limited (India), National Nature Science Foundation (China), Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Department of Energy (USA)/Center for Integrated Smart Sensors funded by the Korea Ministry of Science (Korea), National Natural Science Foundation (China)/Shanghai Municipal Education Commission and Shanghai Education Development Foundation (China), European Research Council/European Metrology Research Programme/ UK National Measurement System, National Natural Science Foundation (China), China scholarship Council/China Ministry of Education/Institute of sound and vibration |

| 4 | Modeling | 5 (3) | 2008–2017 | 0.5 | Air Force Office of Scientific Research (USA), Air Force Office of Scientific Research (USA), a NSFC project of China |

| 5 | Vibration | 8 (1) | 2004–2015 | 0.67 | Energy Efficiency & Resources of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation/Creative Research Initiatives |

| 6 | Biology | 6 (5) | 2011–2019 | 0.67 | Russian Science Foundation/Alexander von Humboldt Foundation/European Commission, National Key R&D Project from Minister of Science and Technology (China), Basic Science Research Program (Korea)/Center for Integrated Smart Sensors as Global Frontier Project, R&D Center for Green Patrol Technologies through the R&D for Global Top Environmental Technologies program funded by the Korean Ministry of Environment, Paul Ivanier Center for Robotics and Manufacturing Research/Pearlstone Center for Aeronautics Research |

| 7 | Sensors | 5 (4) | 2007–2016 | 0.5 | Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, NSSEFF/fellowship/ NSF/ Ben Franklin Technology PArtners/the Center for Dielectric Studies/ARO/DARPA/the Materials Research Institute/U.S Army Research Laboratory, Converging Research Center Program by the Ministry of Education Science and Technology (Korea), Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea |

| 8 | MEMS/NEMS | 15 (7) | 2006–2019 | 1.07 | National Science Foundation (China), the Basic Science Research Program, through the National Research Foundation of Korea, European Research Council, Ministry of Education (Malaysia), Office of Basic Energy Sciences Department of Energy (USA), International Research and Development Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea |

| 9 | Fluids | 8 (3) | 2013–2020 | 1.00 | Ministry of Higher Education (Malaysia), National Natural Science Foundation (China), Australian Research Council/FCSTPty Ltd |

| 10 | Ambient | 11 (4) | 2014–2020 | 1.57 | Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (USA), Portuguese Foundation of Science and Technology, European Regional Development Fund, National Natural Science Foundation of China |