Rapid Monitoring of Viable Genetically Modified Escherichia coli Using a Cell-Direct Quantitative PCR Method Combined with Propidium Monoazide Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains Culture

2.2. Measurement of Optical Density and Colony-Forming Units

2.3. Primer and Probe Designing for PCR and qPCR Assay

2.4. DNA Isolation and Quantification

2.5. Generation of DNA Standard Curves

2.6. Conventional PCR and Dual-Plex qPCR Analysis

2.7. PMA Treatment for Viable Cell Quantification

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Primer and Probe Specificity and Cell-Direct PCR Capability Assessment

3.2. Evaluation of Dual-Plex qPCR Performance on DNA

3.3. Cell-Direct Dual-Plex qPCR Performance

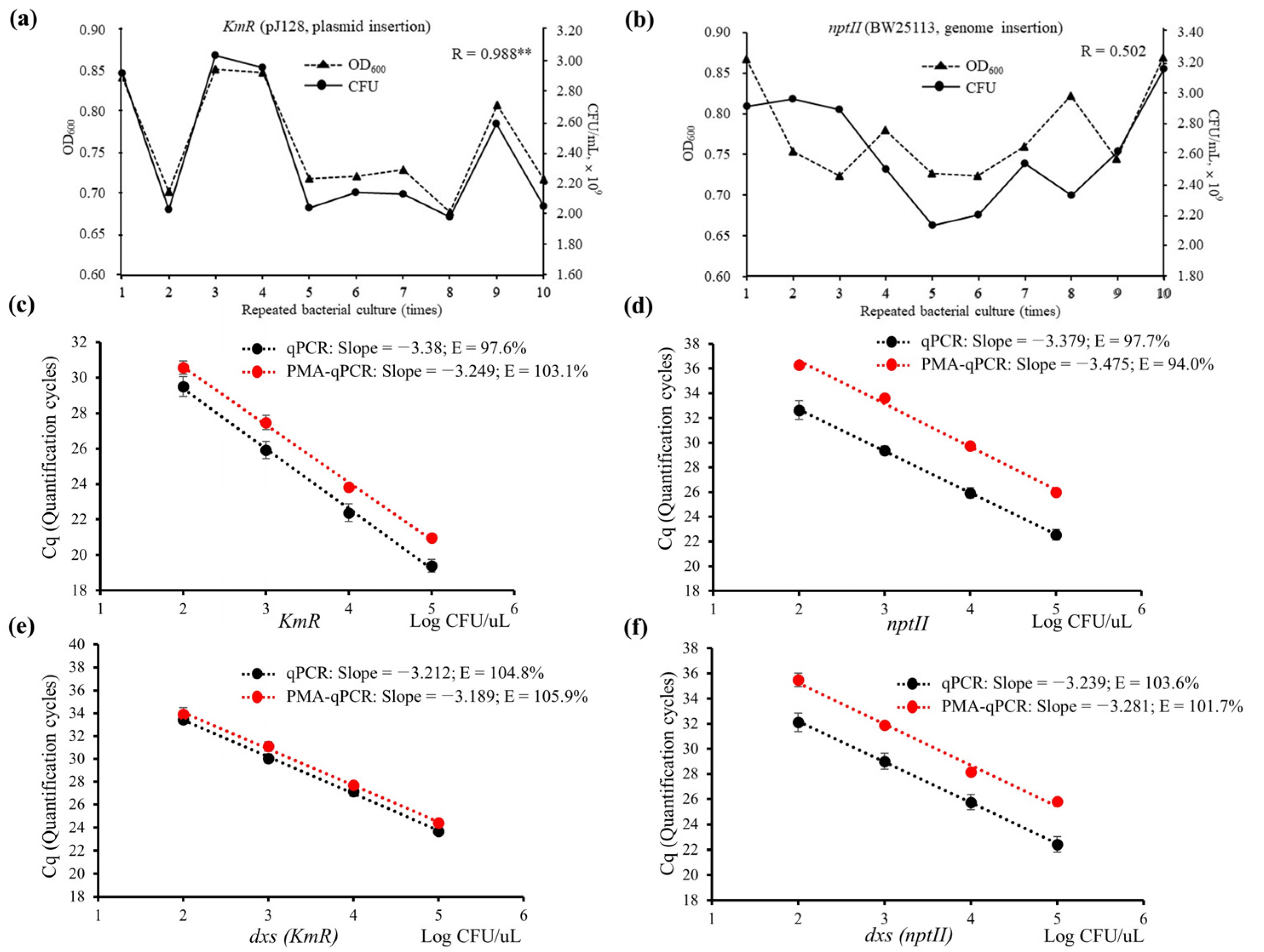

3.3.1. Evaluation of OD and CFU

3.3.2. Evaluation of Matrix Effect

3.3.3. Assay Parameters

3.4. Viable Bacterial Cell Detection Using PMA-qPCR

3.4.1. PMA-qPCR Performance for Both Bacterial Strains

3.4.2. Sensitivity of PMA-qPCR to Detect Viable Cells

3.4.3. Evaluating the Copy Numbers of Antibiotic Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fraiture, M.A.; Deckers, M.; Papazova, N.; Roosens, N.H.C. Are antimicrobial resistance genes key targets to detect genetically modified microorganisms in fermentation products? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 331, 108749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean Biosafety Clearing House (KBCH). LMO Status: Approval Report Status. 2022. Available online: https://www.biosafety.or.kr/portal/page/f_02 (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Paracchini, V.; Petrillo, M.; Reiting, R.; Angers-Loustau, A.; Wahler, D.; Stolz, A.; Schönig, B.; Matthies, A.; Bendiek, J.; Meinel, D.M.; et al. Molecular characterization of an unauthorized genetically modified Bacillus subtilis production strain identified in a vitamin B2 feed additive. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraiture, M.A.; Deckers, M.; Papazova, N.; Roosens, N.H.C. Detection strategy targeting a chloramphenicol resistance gene from genetically modified bacteria in food and feed products. Food Control 2020, 18, 106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiture, M.A.; Deckers, M.; Papazova NRoosens, N.H.C. Strategy to Detect Genetically Modified Bacteria Carrying Tetracycline Resistance Gene in Fermentation Products. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiture, M.A.; Bogaerts, B.; Winand RDeckers, M.; Papazova, N.; Vanneste, K.; De Keersmaecker, S.C.J.; Roosens, N.H.C. Identification of an unauthorized genetically modified bacteria in food enzyme through whole-genome sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daddy Gaoh, S.; Kweon, O.; Lee, Y.-J.; Hussong, D.; Marasa, B.; Ahn, Y. A propidium monoazide (PMAxx)-droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for the detection of viable Burkholderia cepacia complex in nuclease-free water and antiseptics. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Chen, L.; Ahmed, T.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Li, B.; An, Q. Development of droplet digital PCR assay for detection of seed-borne Burkholderia glumae and B. gladioli causing bacterial panicle blight disease of rice. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, J.; Alavez, V.; Cerritos, R.; Andraca-Gómez, G.; Fornoni, J.; Wegier, A. Residual effects of transgenic cotton on the intestinal microbiota of Dysdercus concinnus. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidstedt, M.; Rådström, P.; Hedman, J. PCR inhibition in qPCR, dPCR and MPS—mechanisms and solutions. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.C.; Turner, R.J. Assessing Microbial Monitoring Methods for Challenging Environmental Strains and Cultures. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 13, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijnen, L.; Medema, G. Quantitative detection of E. coli, E. coli O157 and other shiga toxin producing E. coli in water samples using a culture method combined with real-time PCR. J. Water Health 2006, 44, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.J.; Kim, S.J. Detection of human adenoviruses and enteroviruses in Korean oysters using cell culture, integrated cell culture-PCR, and direct PCR. J. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Walch, G.; Knapp, M.; Rainer, G.; Peintner, U. Colony-PCR is a rapid method for DNA amplification of hyphomycetes. J. Fungi. 2016, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Amar, A.; Oueslati, S.; Mliki, A. Universal direct PCR amplification system: A time- and cost-effective tool for high-throughput applications. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Bell, K.N.; Loker, R.N. qPCR and qRT-PCR analysis: Regulatory points to consider when conducting biodistribution and vector shedding studies. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 20, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickley, J.; Short, J.K.; McDowell, D.G.; Parkes, H.C. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of Listeria monocytogenes in diluted milk and reversal of PCR inhibition caused by calciumions. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 22, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, A.; Oueslati, S.; Ghorbel, A.; Mliki, A. Prediction and early detection of mycotoxigenic Fusarium culmorum in wheat samples by direct PCR-based procedure. Food Control 2012, 23, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudi, K.; Moen, B.; Dromtorp, S.M.; Holck, A.L. Use of ethidium monoazide and PCR in combination for quantification of viable and dead cells in complex samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wideman, N.E.; Oliver, J.D.; Crandall, P.G.; Jarvis, N.A. Detection and potential virulence of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) Listeria monocytogenes: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Ara, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Takai, Y.; Okumura, Y.; Baba, M.; Datsenko, K.A.; Tomita, M.; Wanner, B.L.; Mori, H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: The Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 2006.0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Lee, B.R.; Cho, S.; Cho, Y.B.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, T.J.; Kim, S.C.; Cho, B.K. Determination of single nucleotide variants in Escherichia coli DH5α by using short-read sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbrecht, K.C.; Putonti, C.; Koenig, D.W.; Wolfe, A.J. Draft Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli K-12 (ATCC 29425). Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00574-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, J.A.; Russell, N.B.; Whelan, M.A. A method for the absolute quantification of cDNA using real-time PCR. J. Immunol. Methods. 2003, 278, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, R. Quantification on the Light Cycler. In Rapid Cycle REAL-Time PCR; Meuer, S., Wittwer, C., Nakagawara, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann, L.; Broll, H.; Dagand, E.; Hildebrandt, S.; Hübert, P.; Kiesecker, H.; Lieske, K.; Mäde, D.; Mankertz, J.; Reiting, R.; et al. Guidelines for the Validation of Qualitative Real-Time PCR Methods by Means of a Collaborative Study; Technical Report BVL; Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety: Brunswick, Germany, 2016; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Network of GMO Laboratories (ENGL). Definition of Minimum Performance Requirements for Analytical Methods for GMO Testing. 2015. Available online: http://gmo-crl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/doc/MPR%20Report%20Application%2020_10_2015.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Sung, J.; Hawkins, J.R. A highly sensitive internally-controlled real-time PCR assay for mycoplasma detection in cell cultures. Biologicals 2020, 64, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Jang, C.S.; Son, J.M.; Hong, K.W. Comparison of Seven Commercial TaqMan Master Mixes and Two Real-Time PCR Platforms Regarding the Rapid Detection of Porcine DNA. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2021, 41, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Shin, S.G.; Hwang, S. Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 123, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, L.; Xie, X.; Chai, A.; Shi, Y.; Fan, T.; Xie, J.; Li, B. An improved method for quantification of viable fusarium cells in infected soil products by propidium monoazide coupled with real-time PCR. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strains | Insertion Form | Target Genes | Primer/Probe Sequence | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJ281 BW25113 | Plasmid | Kanamycin resistance (KmR) | KmR-F: 5′-CATCATTGGCAACGCTACCTTTG-3′ KmR-R: 5′-GAGCCATATTCAACGGGAAACGT-3′ KmR-Probe: 5′- FAM-CAACTCTGGCGCATCGGGCTTCCC-BHQ1–3′ | 185 |

| pJ281 BW25113 | Genome | Kanamycin/neomycin resistance (nptII) | nptII-F: 5′-CGGGTAGCCAACGCTATGTC-3′ nptII-R: 5′-GAACTGTTCGCCAGGCTCAA-3′ nptII-Probe: 5′-FAM-ACCCAGCCGGCCACAGTCGA-BHQ1–3′ | 173 |

| Escherichia coli | Genome (taxon-specific) | D-1- deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase (dxs) | dxs-F: 5′-AAGGCATTGTGAAGCGTCGT-3′ dxs-R: 5′-CTGGCGGCCATTTCCAGAAT-3′ dxs-Probe: 5′-Hex-CGCTGAACGCCACGCTGGTCG-BHQ1–3′ | 160 |

| Strains | Target Genes | Dilutions | 10−1 | 10−2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 | LB Broth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJ281 | dxs | PMA-Cq | 24.43 ± 0.20 (Cq:23.67) | 27.70 ± 0.24 (Cq:27.17) | 31.09 ± 0.39 (Cq:30.04) | 33.93 ± 0.57 (Cq:33.42) | 37.83 ± 0.07 (Cq:35.97) | 37.74 ± 0.81 (Cq:36.45) | 37.86 ± 0.32 (Cq:36.26) |

| RSDr % | 0.82 | 0.88 | 1.27 | 1.67 | 0.20 | 2.13 | 0.47 | ||

| KmR | PMA-Cq | 20.96 ± 0.04 (Cq:19.40) | 23.82 ± 0.19 (Cq:22.38) | 27.48 ± 0.41 (Cq:25.91) | 30.57 ± 0.37 (Cq:29.49) | 34.30 ± 0.73 (Cq:32.16) | 36.18 ± 0.64 (Cq:34.11) | 37.69 ± 0.42 (Cq:36.57) | |

| RSDr % | 0.17 | 0.78 | 1.50 | 1.21 | 2.14 | 1.78 | 1.12 | ||

| BW25113 | dxs | PMA-Cq | 25.79 ± 0.13 (Cq:22.41) | 28.15 ± 0.10 (Cq:25.75) | 31.89 ± 0.15 (Cq:29.01) | 35.48 ± 0.52 (Cq:32.12) | 37.71 ± 0.03 (Cq:35.17) | UD (Cq:37.35) | UD (Cq:38.12) |

| RSDr% | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 1.47 | - | - | - | ||

| nptII | PMA-Cq | 25.99 ± 0.12 (Cq:22.53) | 29.76 ± 0.09 (Cq:25.92) | 33.61 ± 0.03 (Cq:29.38) | 36.29 ± 0.24 (Cq:32.64) | 37.84 ± 0.86 (Cq:35.88) | 37.06 ± 0.25 (Cq:38.39) | UD (Cq:38.69) | |

| RSDr % | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 2.28 | 0.68 | - |

| Strains | Targets/Dilutions | 10−1 | 10−2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−6 | LOD 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJ281 | CFU/µL | 239,000 | 23,900 | 2390 | 239 | 23.9 | 2.39 | 69 (29–693) |

| dxs | 8/8(100%) | 8/8(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 16/20(80%) | 8/20(40%) | ||

| KmR | 8/8(100%) | 8/8(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 14/20(70%) | ||

| BW25113 | CFU/µL | 262,000 | 26,200 | 2620 | 262 | 26.2 | 2.62 | 67 (40–111) |

| dxs | 8/8(100%) | 8/8(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 14/20(70%) | 2/20(10%) | ||

| nptII | 8/8(100%) | 8/8(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 20/20(100%) | 17/20(85%) | 8/20(40%) |

| Strains | Targets | qPCR (DNA) | Plasmid Copy Number (DNA) | qPCR (Cell) | Plasmid Copy Number (Cell) | PMA-qPCR (Cell) | Viable Cell Count/mL (×109) | Plasmid Copy Number (PMA-Cell) | CFU/mL (×109) | Bias % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJ281 | KmR | 10.64 ± 0.23 | 9.89 | 17.49 ± 0.21 | 12.78 | 18.05 ± 0.15 | 28.84 ± 8.67 | 9.72 | 2.39 ± 0.03 | 24.09 |

| dxs | 14.61 ± 0.34 | 22.61 ± 0.21 | 22.73 ± 0.13 | 2.97 ± 1.32 | ||||||

| BW25113 | nptII | 16.04 ± 0.33 | 0.93 | 20.37 ± 0.28 | 0.77 | 22.16 ± 0.10 | 2.68 ± 2.26 | 1.02 | 2.62 ± 0.03 | −8.63 |

| dxs | 15.91 ± 0.36 | 20.53 ± 0.34 | 22.77 ± 0.29 | 2.63 ± 1.39 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, Y.; Qu, B.; Lee, B. Rapid Monitoring of Viable Genetically Modified Escherichia coli Using a Cell-Direct Quantitative PCR Method Combined with Propidium Monoazide Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11051128

Qin Y, Qu B, Lee B. Rapid Monitoring of Viable Genetically Modified Escherichia coli Using a Cell-Direct Quantitative PCR Method Combined with Propidium Monoazide Treatment. Microorganisms. 2023; 11(5):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11051128

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Yang, Bo Qu, and Bumkyu Lee. 2023. "Rapid Monitoring of Viable Genetically Modified Escherichia coli Using a Cell-Direct Quantitative PCR Method Combined with Propidium Monoazide Treatment" Microorganisms 11, no. 5: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11051128

APA StyleQin, Y., Qu, B., & Lee, B. (2023). Rapid Monitoring of Viable Genetically Modified Escherichia coli Using a Cell-Direct Quantitative PCR Method Combined with Propidium Monoazide Treatment. Microorganisms, 11(5), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11051128