Abstract

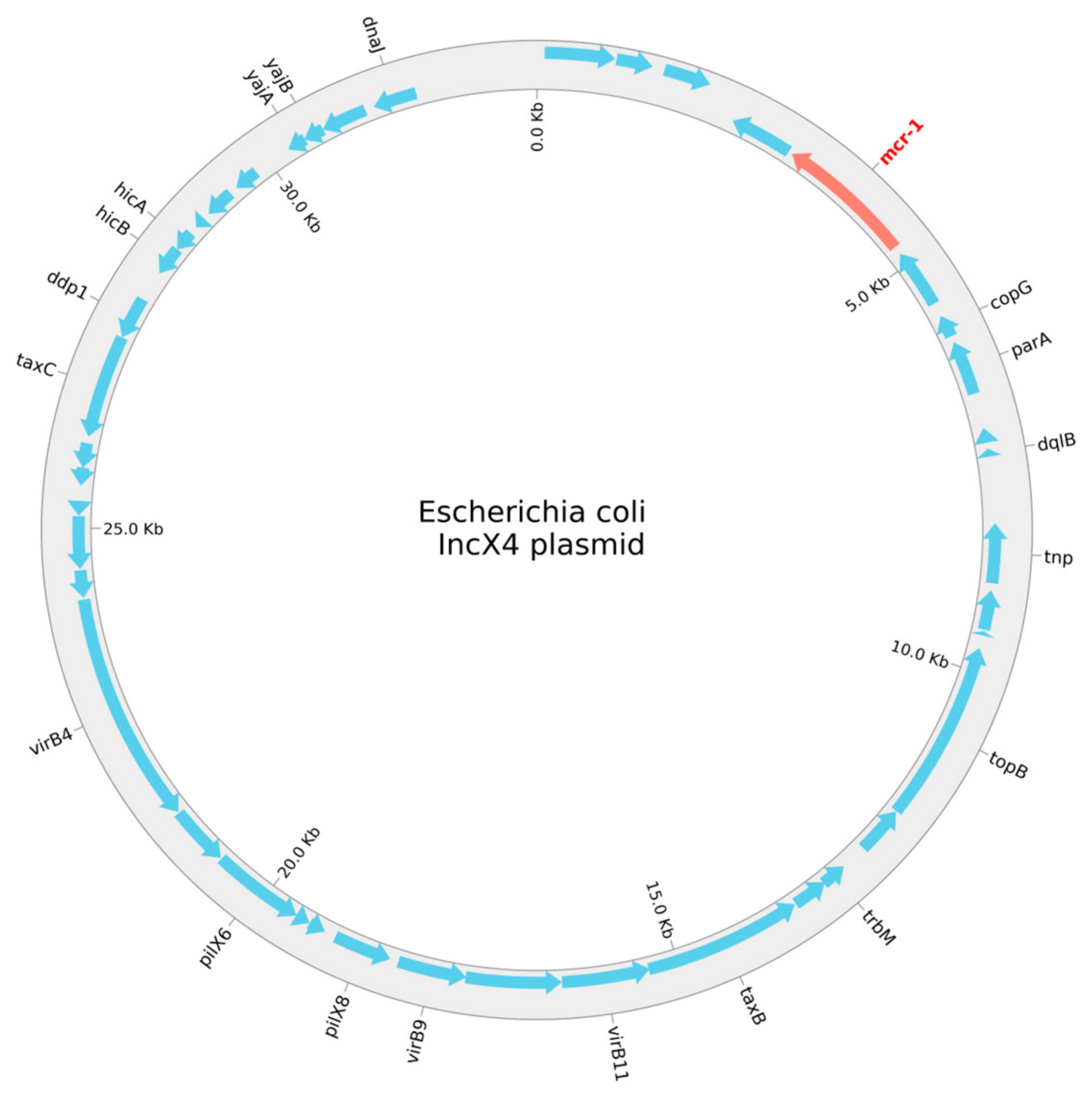

Colistin resistance poses a significant clinical challenge, particularly in Gram-negative bacteria. This study investigates the occurrence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance among Enterobacterales isolates (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter spp.) and non-fermentative rods (Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). We analyzed 114 colistin-resistant isolates that were selected, based on resistance phenotypes, and isolated between 2019 and 2023. To achieve this, we used the rapid immunochromatographic test, NG-Test® MCR-1; multiplex PCR for mcr-1 to mcr-8, and real-time PCR for mcr-1 and mcr-2. One E. coli isolate was identified as carrying the mcr-1 gene, confirmed by NG-Test® MCR-1, multiplex PCR and whole-genome sequencing. This strain, belonging to ST69, harbored four plasmids, harboring different antimicrobial resistance genes, with mcr-1 being located on a 33,304 bp circular IncX4 plasmid. No mcr-2 to mcr-8-positive isolates were detected, prompting further investigation into alternative colistin resistance mechanisms. This is the first report of a mcr-1-positive, colistin-resistant E. coli isolated from a human clinical sample in the North-East of Romania.

1. Introduction

The rise of antibiotic resistance allows non-susceptible bacteria to outcompete susceptible isolates, especially in selective environments. Furthermore, bacteria are increasingly developing resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, complicating the treatment of infectious diseases due to the limited availability of effective antibiotics [1].

The abuse of antibiotics has accelerated the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, resulting in a major global health concern, in terms of antimicrobial resistance [2].

Because of the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) isolates, polymyxins (colistin and polymyxin B) have become the last-resort antibiotic, forcing the World Health Organization in 2011 to reclassify polymyxins as critically important for human medicine [3,4,5].

One of the first known mechanisms of resistance to polymyxin was chromosomally mediated, with modifications of Lipid A by a two-component regulatory system, resulting in the reduction in polymyxin affinity [6,7]. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mediated by mcr-1, a gene encoding mobilized colistin resistance, was reported for the first time, in 2015, in China [8].

After that, mcr-1 has been detected in more than 50 countries. At the moment, strains that carry mcr-1 have been isolated from raw meat (pork and poultry), from animals, and from environmental and clinical samples. To date, 10 variants of mcr genes have been discovered [9]. These genes are encoded in plasmids and can be transferred horizontally.

The overall average prevalence of mcr genes was 4.6% (ranging from 0.1% to 9.3%), with the highest prevalence observed in environmental samples at 22% (2.8–47.8%), followed by animal samples at 11% (0.3–22.4%), food samples at 5.4% (0.6–11.6%), and human samples at 2.5% (0.1–5.1%) [10].

The global prevalence of mcr-positive colistin-resistant E. coli is 6.51% [11]. According to 2023 data from the National Database of Antibiotic Resistant Organisms, Enterobacterales shows a prevalence of 3.6% for mcr-1 and 1.1% for mcr-9, while mcr-3 is found in 4.5% of Aeromonas spp. and mcr-10 in 0.2% of Enterobacter kobei [12].

Despite ongoing research efforts, the molecular mechanisms underlying colistin resistance and heteroresistance remain not fully understood [13,14], and there is still limited information on their spread and impact [15,16,17].

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has emerged as a vital tool for exploring both known and new mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, offering substantial potential for infection control and surveillance [18].

The aim of this study is to identify the antibiotic-resistant phenotypes and if the isolates—originating from the “St. Spiridon” County Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi, Romania—carry one of the ten variants of mcr genes, in order to emphasize the importance of the situation in the North-East region of Romania.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification

We conducted a retrospective–prospective study and analyzed 114 non-duplicate isolates of colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, from a total of 4.659 MDR Gram-negative rods, isolated between 2019 and 2023 from “St. Spiridon” County Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iași, Romania.

All isolates were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) or conventional biochemical assays.

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by both the disc diffusion method and broth microdilution method in an automated system on the MICRONAUT-S (Merlin, Forchtenberg, Germany), and the interpretation of the results was performed according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) standard, applicable at the time [19,20,21,22,23]. The results of the antimicrobial susceptibility tests were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS®) Statistics version 25 (IBM-SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For colistin, The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and EUCAST have established colistin susceptibility testing through the determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) using broth microdilution, a standardized method accepted worldwide as gold-standard according to ISO-20776 [24].

2.3. Phenotypic Detection of mcr-1 Production by Immunochromatographic Test

For this examination, we employed NG-Test® MCR-1 (NG BIOTECH Laboratories, Guipry, France) and examined 114 Gram-negative rods resistant to colistin. The NG-Test MCR-1 LFA is a swift, disposable lateral-flow immunoassay utilizing streptavidin-labeled anti-MCR-1 mouse monoclonal antibodies for the direct detection of MCR-1 from bacterial colonies [25].

2.4. Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Detection of mcr Genes

The protocol used is the one recommended in a laboratory manual for carbapenem and colistin resistance detection and characterization for the survey of carbapenem- and/or colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae [26].

The detection of mcr-1 to mcr-8 genes was performed by using 2 conventional multiplex PCR reactions (adapted from Rebelo et al.), targeting the genes mcr1-mcr5 (multiplex PCR 1) and mcr-6-mcr-8 (multiplex PCR 2) and with real-time PCR (Colistin–R ELITe MGB® Kit) for mcr-1 and mcr-2 genes [27].

The reference strain included in the reactions was E. coli NCTC 13846. The amplification program is the one recommended by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) manual.

2.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Bioinformatic Analysis

Genomic characterization of the E. coli strain was performed by WGS. WGS data were obtained and analyzed according to common WGS-based genome analysis methods and standard protocols for national CRE surveillance and integrated outbreak investigations [28,29].

Genomic DNA was extracted using Invitrogen™ PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany).

The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA were evaluated using the Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) and Tapestation (Agilent, D1000 ScreenTape Assay, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The protocol for sample preparation for sequencing, i.e., library preparation, was carried out with the commercial Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit v3 (96 samples) and IDT® for Illumina® DNA/RNA UD Indexes Set A, Tagmentation (96 indexes, 96 samples). The amount of DNA/sample used for library preparation was 1 ng.

The platform used for WGS was MiSeq® (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing data were obtained by short-read technology; the read length defined before sequencing started was 251 bp [30,31].

Illumina WGS analysis was performed using the pipeline provided within Ridom SeqSphere+ (v. 9.0.10 Ridom© GmbH, Münster, Germany). In short, quality control of the raw sequence data files was performed using FASTQC (v. 0.12.1), and the paired-end reads were assembled de novo using SPAdes, version 3.15.4.

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing was performed to better define the genomic landscape of the resistant genes. ONT libraries were prepared using the rapid DNA barcoding protocol (SQK-RBK114.24, RBK_9176_v114_revN_30Sept2024) and sequenced on a MinION device with R10.4.1 DNA flow cell as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The ONT reads generated were basecalled using dorado (version 0.7.3+6e6c45c) using the “sup” basecalling model (dna_r10.4.1_e8.2_400bps_sup@v5.0.0), demultiplexed, and the barcodes were trimmed using the same software. The results were assessed with NanoStat (v. 1.6.0) and NanoPlot v. 1.43.1, (https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/34/15/2666/4934939 accessed on 16 October 2024). Filtering was performed for a mean phred score of 20 and a minimum length of 5000bp. Assembly was performed with Trycyclerv. 0.5.3, (Flye, v. 2.9.5-b1801; Minimap v. 2.28-r1209/Miniasm v. 0.3-r179 and raven v. 1.8.3) (https://genomebiology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13059-021-02483-z accessed on 16 October 2024) and polished using Medaka (v. 1.8.0, using Nanopore reads) and Polypolish (v. 0.6.0, using Illumina reads) (https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.001254 accessed on 16 October 2024).

The analysis pipeline included MLST, AMRFinder Plus v. 3.11.14), Chromosome, and Plasmid overview. To check the results, a second, web-based pipeline was used (Center for Genomic Epidemiology, http://genomicepidemiology.org accessed on 16 October 2024), pertaining to Resfinder v. 4.6.0, PlasmidFinder (v. 2.0.1), and pMLST (v. 0.1.0), to examine and categorize AMR-resistant genes and plasmids, according to Carattoli A. et al. [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. The serotype was predicted from the WGS data using ECTyper (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8767331/ accessed on 16 October 2024). Plasmid annotation was performed using bakta v. 1.8.2, (https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000685), and visualization was performed using pyCirclize, (https://github.com/moshi4/pyCirclize, accessed 9 November 2024).

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Identification

The study group included 114 colistin-resistant Gram-negative rods, which were selected, based on resistance phenotypes, from the total number of multidrug-resistant isolates collected from patients hospitalized between 2019 and 2023 in “St. Spiridon” County Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iași, Romania.

The breakdown by species of the study group with isolates resistant to colistin was as follows: Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 91), Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 12), Enterobacter cloacae complex (n = 7), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 3), and Escherichia coli (n = 1). The studied bacteria were mostly K. pneumoniae isolates, because they are the ones with higher percentages of colistin resistance, and the other rods, e.g., E. coli and P. aeruginosa, are rarely resistant to colistin in our hospital.

Most isolates (n = 50) were collected from wound secretions, tracheal aspirates, burn wounds, and surgical wounds. Additional sources included urocultures (n = 20), tracheal aspirates (n = 15), blood cultures (n = 8), catheter tips (n = 5), pharyngeal exudates (n = 2), and other pathological samples (n = 14).

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

We selected 114 colistin-resistant isolates and included rods with different antibiotypes to complete the picture regarding antibiotic resistance, from our geographic area.

The colistin resistance rate among Gram-negative rods, over all the years included in this study, was 2.45%, which is still a low percentage, though it raises a cause for concern.

The antibiotic resistance percentages of colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates (91 isolates obtained between 2019 and 2023) from our study are presented in Table 1. More than half of the isolates were resistant to carbapenems, and all of the isolates were resistant to third cephalosporins. The lowest resistance percentages were observed for aminoglycosides, with only 30% of the strains being resistant to aminoglycosides; however, in 2023, the percentages doubled.

Table 1.

Evolution of AMR of Klebsiella pneumoniae between 2020 and 2023.

In 2019, we included in our study a single colistin-resistant isolate of K. pneumoniae, which remained susceptible to carbapenems.

In 2022, only four isolates of K. pneumoniae included in our study were susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam, while the remaining isolates exhibited resistance, including resistance to ceftolozane-tazobactam and imipenem-relebactam. In 2023, 54% of the Klebsiella isolates included in our study were resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam, 92% to ceftolozane-tazobactam, and only 61.5% to imipenem-relebactam.

We analyzed one E. coli isolate, selected from our bacterial samples, that was resistant to colistin. This isolate has garnered significant attention due to its production of ESBLs and its resistance to aminoglycosides, cotrimoxazole, and fluoroquinolones. Notably, the strain remains susceptible to carbapenems, ceftazidime-avibactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, and tigecycline. The colistin MIC was 8 micrograms per milliliter.

Regarding the antibiotic resistance of A. baumannii (n = 12) isolates, in 2019, the rods were shown to have increased exposure susceptibility only to imipenem and meropenem. In 2020 and 2021, isolates were classified as extensively drug-resistant (XDR), with a colistin MIC greater than 64 micrograms per milliliter and one isolate with 16 micrograms per milliliter. In 2022, we included in our study group one A. baumannii strain that was susceptible only to aminoglycosides, and in 2023, we included a strain that was XDR.

The P. aeruginosa isolates were resistant to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones but susceptible to ceftazidime-avibactam and susceptible to increased exposure to aztreonam and cefepime, with an MIC of colistin equal to 16 micrograms per milliliter.

All of the Enterobacter cloacae complex colistin-resistant species that we included in our study were susceptible of most of the antibiotic classes, but the colistin MICs were 16 and 64 micrograms per milliliter.

3.3. Phenotypic Detection of mcr-1 Production by Immunochromatographic Test

Of the 114 isolates we tested using rapid immunochromatographic assays—NG-Test® MCR-1 (NG BIOTECH Laboratories, Guipry, France)—one E. coli isolate tested positive for carrying the mcr-1 gene.

3.4. Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Detection of mcr Genes

Out of 114 isolates, we tested 24 bacteria with multiplex PCR and the others (n = 90), with real-time PCR.

E. coli isolate, which tested positive using the rapid immunochromatographic test (NG-MCR1) was subsequently confirmed by multiplex PCR as carrying the mcr-1 gene, variant mcr-1.1 (AMRfinder plus; mcr-1.26 Resfinder).

The other isolates (n = 113) tested by immunochromatographic rapid tests, multiplex PCR, and real-time PCR were negative; none of the eight mcr gene variants targeted by the PCR kit were detected.

3.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Bioinformatic Analysis

The mcr-1-positive E. coli isolate was further investigated through WGS, which detected beta-lactam resistance genes (bla-TEM-1, blaCTX-M-1 (ESBL), and blaCTX-M-27 (ESBL)), as well as aminoglycoside resistance (aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-la, aadA5, aph(3”)-lb, and aph(6)-ld), cotrimoxazole resistance (sul1, sul2, and dfrA17), and fluoroquinolone resistance (qnrS1).

The E. coli strain was assigned sequence type (ST) 69 and had a predicted serotype of O15:H19. The chromosomal point mutations for the E. coli strain, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chromosomal point mutation of mcr-1-positive E. coli strain.

3.6. PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing (pMLST)

The program PlasmidFinder, v2.0.1, was used to search the mcr-1-positive E. coli for plasmids. We found seven plasmid replicons—Col156, IncFIA, IncFIB, IncFII, IncN, IncX1, and IncX4—belonging to four individual, circular plasmids. The replicons, length, antimicrobial resistance genes, positions in the plasmid, coverage, identity, and accession numbers are given in Table 3, and a schematic circular representation of the E. coli IncX4 plasmid is shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Plasmids found in the mcr-1-positive E. coli strain.

Figure 1.

A schematic circular representation of the E. coli IncX4 plasmid.

4. Discussion

The global health system faces a significant challenge with the widespread resistance to various antibiotics, including beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, and carbapenems. Colistin is considered the last line of defense in treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative rods, particularly Enterobacterales [39,40,41].

In our study, we present the first mcr-1-carrying E. coli, isolated from the north-east of Romania. This strain was identified in April 2023, from a 63-year-old female patient admitted to the Emergency Care Unit of the “St. Spiridon” County Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iași, with a sacral eschar and other comorbidities (multiple sclerosis and intestinal occlusion). From the patient’s history, we noticed that she had multiple hospitalizations, some of them in other health units as well.

Fortunately, in our hospital, the patient was only admitted to the Emergency Care Unit; she was not hospitalized for long time, and we have not identified other similar isolates from this patient.

This E. coli strain showed susceptibility to carbapenems, ceftazidime-avibactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, and tigecycline.

In Romania, there is only one report of an E. coli mcr-1-positive strain, isolated from poultry samples, from two abattoirs in the north-east of Romania [42].

In Germany, other authors have also found the E. coli mcr-1-positive strain, but it was isolated from pigs [43].

In Greece, Protonotariou et al. identified a mcr-1-positive E. coli strain, from a pediatric patient, with the same antibiotic type (extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing, and aminoglycoside-, fluoroquinolone-, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-resistant, but carbapenem-susceptible) [44].

Another study, conducted in China, identified colistin-resistant, multidrug-resistant E. coli strains carrying the mcr-1 gene, from clinical samples (producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, resistant to aminoglycosides, and resistant to fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, but sensitive to carbapenems) [45].

A key factor contributing to bacterial resistance to antibiotics is the presence of associated resistance genes. Some studies have demonstrated that MDR is linked to bacteria harboring these resistance genes. The blaCTX-M gene is the most prevalent ESBL, encoding gene found in both humans and animals [46,47]. Our research has shown that the E. coli strain was carrying two different blaCTX-M genes and a blaTEM gene, which were found in strains isolated from animal sources [48,49].

In our study, PlasmidFinder revealed that the E. coli isolate harbored different plasmid scaffolds, differing in sizes and structures, including IncX4, IncFIA, and IncFII. BLAST analysis revealed that the most likely localization of the mcr-1 gene was on the conjugative IncX4 plasmid. These findings are consistent with previous reports, like the one from Sadek et al., that showed IncI2 as being the most prevalent plasmid backbone, followed by IncX4 and IncHI2 [50]. Göpel et al. also found that the predominant mcr-1.1-harboring plasmid types were IncHI2, IncX4, and IncI2 [41]. Third-generation sequencing would be needed to establish the full genomic landscape of the bacteria.

For the E. coli, mcr-1-positive strain, we wanted to investigate the observed quinolone resistance, and we examined point mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE. The same point mutations found by Resfinder in the E. coli strain have been found by other authors [51,52,53]; we identified missense mutations at two positions: TCG -> TTG in gyrA and AGC -> ATT in parC; we have not identified any mutations in the other positions (gyrB and parE).

E. coli ST69 belongs to the multidrug-resistant phylogenetic group D, which is commonly associated with urinary tract infections and exhibits widespread antibiotic resistance across various hosts [54,55]. ST69 strains have been reported to carry resistance genes on plasmids such as the blaVIM-harboring IncA, blaNDM-1-harboring IncI1, and mcr-1-harboring IncHI2 [56,57,58].

In the present study, we identified a ST69 E. coli strain, containing seven replicons (IncFIA, IncFIB, IncFII, IncN, IncX1, IncX4, and Col156) and harboring the blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-27 genes. IncF plasmids, one of the most common incompatibility types, are globally distributed in Enterobacterales and vary in size (50–200 kb) and replicon types. These plasmids carry numerous antibiotic resistance genes conferring resistance to major antibiotic classes such as beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, aminoglycosides, quinolones, and tetracyclines [57,58]. The association of the IncF plasmid with blaCTX-M, observed in E. coli ST69, has been frequently documented in E. coli isolates from both human and animal sources. For example, the IncF plasmid R100 is responsible for spreading blaCTX-M-14 in the United Kingdom and France [59,60].

Based on our research, E. coli ST69 was identified as a CTX-M-type ESBL-producing isolate. While CTX-M-14 and CTX-M-15 are the most common variants, CTX-M-27 has been rapidly increasing in prevalence [61]. Alarmingly, the detection of CTX-M-27 in E. coli isolates from patients has been rising, particularly in clonal groups such as ST10, ST69, and ST131 [61,62].

Regarding the colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae strains investigated in our study, they did not present the mcr-1 to mcr-8 genes. Therefore, colistin resistance is not plasmid-mediated for the K. pneumoniae strains circulating in our hospital. However, another study from the north-east of Romania showed that colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae strains, from clinical samples, tested positive for the mcr-1 gene using the NG Test® MCR-1 assay [63].

Although colistin currently maintains a high level of activity against most isolates of K. pneumoniae, the decline in activity against carbapenem-resistant isolates is worrying. It has also been recognized that the increased use of colistin is responsible for outbreaks caused by intrinsically polymyxin-resistant species and the increasing isolation of colistin-resistant strains of K. pneumoniae. Researchers have reported a correlation between the use of colistin to treat infections caused by carbapenem-resistant strains and the subsequent emergence of colistin-resistant strains [46].

A study in Iran showed a strong association between carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae and increased resistance to colistin. Based on the higher percentage of colistin resistance observed among carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (31.7%), continued monitoring of colistin susceptibility use will be necessary [47]. More than half of the K. pneumoniae strains included in our study were carbapenem-resistant strains.

An upward trend in colistin resistance, increasing from 14.9% in 2016 to 36.2% in 2021, was also reported in a hospital in Thailand [64].

In Europe, the evolving colistin resistance is more pronounced in southern countries (notably Greece and Italy) [65]. The prevalence of colistin resistance among carbapenemase-producing strains was reported to be high in Italy (43%), according to Monaco et al., and varied between 10.7 and 25.6% in another study conducted by Parisi et al. [66,67].

In Romania, colistin resistance rates in K. pneumoniae isolates resistant to carbapenems rose from 29.1% in 2019 to 36.7% in 2021 [68,69]. The study of Cireșă et al. also revealed a significant rise in colistin resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates resistant to carbapenems from 54.7% to 80%, between 2019 and 2021 [70].

5. Conclusions

This is the first clinically isolated E. coli strain which carries the mcr-1 gene, variant mcr-1.1, that has been reported in the north-east of Romania, originating from a 63-year-old female patient.

This strain of E. coli was classified as sequence type (ST) 69 through multilocus sequence typing.

The ease with which these resistance genes can be transmitted raises a strong alarm signal and deserves all our attention.

The Klebsiella pneumoniae strains that predominated in our sample group tested negative for the mobilized colistin resistance mechanism. Further investigation will be conducted to determine the underlying mechanism of colistin resistance.

Our study completes the picture of antibiotic resistance in the north-east of Romania and gives an overview of colistin resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-A.V. and C.T. Methodology, M.-A.V., C.T. and B.-E.L.; Data extraction, synthesis, and interpretation, M.-A.V., C.T., C.L., B.-E.L. and A.-A.M. Writing—reviewing and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported through the platform IOSIN CNEIMPEM (Nicoleta Olguta Corneli) and “NUCLEU” Research Project PN 23 44 03 01 (Cristiana Cerasella Dragomirescu). The majority of the funding was provided by a doctoral grant from “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iași, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Grigore T. Popa” Iași, Romania (IRB number: 133, approval date: 21 December 2021) and by the Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB number: 60, approval date: 9 December 2021).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Molecular Epidemiology for Communicable Diseases Laboratory at the “Cantacuzino” National Medical-Military Institute for Research and Development provided technical support in the Illumina library preparation workflow and bioinformatic analysis. Special thanks are due to Dan Maria and the team from the Microbiology Laboratory, “Sf. Spiridon” Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi, for providing the bacterial strains investigated in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Terreni, M.; Taccani, M.; Pregnolato, M. New antibiotics for multidrug-resistant bacterial strains: Latest research developments and future perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; et al. Antibiotic resistance: The need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, N.; Aranzana-Climent, V.; Magréault, S.; Marchand, S.; Couet, W. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of colistin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.L.; Harris, P.N.A. Colistin resistance: A major breach in our last line of defence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, S.E.; Li, J.; Tsuji, B.T.; Forrest, A.; Bulitta, J.B.; Nation, R.L. Colistin and Polymyxin B dosage regimens against Acinetobacter baumannii: Differences in activity and the emergence of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3921–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Morand, S.; Rolain, J.M. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: Acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.; Hadjadj, L.; Rolain, J.; Olaitan, A.O. Molecular mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: Knowns and unknowns. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; Yu, L.-F.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.H.; Al-Kadmy, I.M.S.; Taha, B.M.; Hussein, J.D. Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: A comprehensive review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 2897–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbediwi, M.; Li, Y.; Paudyal, N.; Pan, H.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; Rajkovic, A.; Feng, Y.; Fang, W.; Rankin, S.C. Global burden of colistin-resistant bacteria: Mobilized colistin resistance genes study (1980–2018). Microorganisms 2019, 7, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Caldes, C.; de Waard, J.H.; Salgado, M.S.; Villacís, M.J.; Coral-Almeida, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Calvopiña, M. World-wide prevalence of mcr-mediated colistin-resistance Escherichia coli in isolates of clinical samples, healthy humans, and livestock—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero-Cáceres, W.; Balcázar, J.L. Evolution and dissemination of mobile colistin resistance genes: Limitations and challenges in Latin American countries. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e567–e568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Detection and Reporting of Colistin Resistance, 2nd ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS); Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/343654/9789240019041-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Stojowska-Swedrzynska, K.; Lupkowska, A.; Kuczynska-Wisnik, D.; Laskowska, E. Antibiotic heteroresistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report 2019; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/surveillance-antimicrobial-resistance-Europe-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 557–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Band, V.I.; Satola, S.W.; Smith, R.D.; Hufnagel, D.A.; Bower, C.; Conley, A.B.; Rishishwar, L.; Dale, S.E.; Hardy, D.J.; Vargas, R.L.; et al. Colistin heteroresistance is largely undetected among Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in the United States. mBio 2021, 12, e02881-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koser, C.U.; Ellington, M.J.; Peacock, S.J. Whole-genome sequencing to control antimicrobial resistance. Trends Genet. 2014, 30, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 9.0. 2019. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 10.0. 2020. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 11.0. 2021. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 12.0. 2022. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 13.0. 2023. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- CLSI. Performance Standard for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 26th ed. CLSI: Malvern, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Volland, H.; Dortet, L.; Bernabeu, S.; Boutal, H.; Haenni, M.; Madec, J.Y.; Robin, F.; Beyrouthy, R.; Naas, T.; Simon, S. Development and Multicentric Validation of a Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Rapid Detection of MCR-1-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01454-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Laboratory Manual for Carbapenem and Colistin Resistance Detection and Characterisation for the Survey of Carbapenem- and/or Colistin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae—Version 2.0; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo, A.R.; Bortolaia, V.; Kjeldgaard, J.S.; Pedersen, S.K.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Hansen, I.M.; Guerra, B.; Malorny, B.; Borowiak, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; et al. Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance determinants, mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 for surveillance purposes. Eurosurveillance 2018, 23, 17-00672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.eurgen-reflabcap.eu/-/media/sites/eurgen-reflabcap/ny-eurgen-reflabcap-common-wgs-protocol-for-cre-and-ccre.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Center for Genomic Epidemiology. Available online: https://www.genomicepidemiology.org (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; García-Fernández, A.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Hasman, H. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartual, S.; Seifert, H.; Hippler, C.; Luzon, M.; Wisplinghoff, H.; Rodrà guez-Valera, F. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for characterization of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4382–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.; Fawley, W.; Kachrimanidou, M.; Bowden, R.; Crook, D.; Fung, R.; Golubchik, T.; Harding, R.; Jeffery, K.; Jolley, K.; et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemee, L.; Dhalluin, A.; Pestel-Caron, M.; Lemeland, J.; Pons, J. Multilocus sequence typing analysis of human and animal Clostridium difficile isolates of various toxigenic types. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.; Falush, D.; Lan, R.; Colles, F.; Mensa, P.; Wieler, L.; Karch, H.; Reeves, P.; Maiden, M.; Ochman, H.; et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: An evolutionary perspective. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 1136–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaureguy, F.; Landraud, L.; Passet, V.; Diancourt, L.; Frapy, E.; Guigon, G.; Carbonnelle, E.; Lortholary, O.; Clermont, O.; Denamur, E.; et al. Phylogenetic and genomic diversity of human bacteremic Escherichia coli strains. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton-Foot, M.; Snyman, Y.; Maloba, M.R.; Whitelaw, A.C. Plasmid-mediated mcr-1 colistin resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. clinical isolates from the Western Cape region of South Africa. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2017, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L.; Ruan, Z.; Feng, Y.; Akova, M.; et al. Prevalence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae recovered from bloodstream infections in China: A multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liang, B.; Xu, X.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Li, P.; Qiu, S.; Song, H. Identification of mcr-1-positive multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from clinical samples in Shanghai China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 29, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciuca, I.E.; Cummins, M.L.; Cozma, A.P.; Rimbu, C.M.; Guguianu, E.; Panzaru, C.; Licker, M.; Szekely, E.; Flonta, M.; Djordjevic, S.P.; et al. Genetic Features of mcr-1 Mediated Colistin Resistance in CMY-2-Producing Escherichia coli From Romanian Poultry. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Göpel, L.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Wolf, S.A.; Semmler, T.; Bauerfeind, R.; Ewers, C. Repeated Occurrence of Mobile Colistin Resistance Gene-Carrying Plasmids in Pathogenic Escherichia coli from German Pig Farms. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protonotariou, E.; Meletis, G.; Malousi, A.; Kotzamanidis, C.; Tychala, A.; Mantzana, P.; Theodoridou, K.; Ioannidou, M.; Hatzipantelis, E.; Tsakris, A.; et al. First detection of mcr-1-producing Escherichia coli in Greece. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 31, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.; Jordan, D.; Wong, H.S.; Johnson, J.R.; Toleman, M.A.; Wakeham, D.L.; Gordon, D.M.; Turnidge, J.D.; Mollinger, J.L.; Gibson, J.S.; et al. First detection of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli in Australian food-producing animals. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2015, 3, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidjabat, H.E.; Seah, K.Y.; Coleman, L.; Sartor, A.; Derrington, P.; Heney, C.; Faoagali, J.; Nimmo, G.R.; Paterson, D.L. Expansive spread of IncI1 plasmids carrying blaCMY-2 amongst Escherichia coli. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cui, L.; Han, Y.; Lin, F.; Huang, J.; Song, M.; Lan, Z.; Sun, S. Characteristics, Whole-Genome Sequencing and Pathogenicity Analysis of Escherichia coli from a White Feather Broiler Farm. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbinosa, I.H. Prevalence and detection of antibiotic-resistant determinant in Salmonella isolated from food-producing animals. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2015, 47, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, M.; Ortiz de la Rosa, J.M.; Abdelfattah Maky, M.; Korashe Dandrawy, M.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Genomic Features of MCR-1 and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales from Retail Raw Chicken in Egypt. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorlozano, A.; Gutierrez, J.; Jimenez, A.; Luna, J.; Martinez, J.L. Contribution of a new mutation in parE to quinolone resistance in extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2740–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarini, L.A.; Darini, A.L. Mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions of gyrA and parC in enterobacteriaceae isolates from Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El-Khier, N.T.; Zaki, M.E.S. Molecular detection and frequency of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli by multiplex allele specific polymerase chain reaction (MAS-PCR). Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2019, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, Â.; Vuotto, C.; Pires, J.; Montenegro, C.; Donelli, G.; Coque, T.M.; Peixe, L. Diversity and biofilm-production ability among isolates of Escherichia coli phylogroup D belonging to ST69, ST393 and ST405 clonal groups. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khonsari, M.S.; Behzadi, P.; Foroohi, F.J.M.G. The prevalence of type 3 fimbriae in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from clinical urine samples. Meta Gene 2021, 28, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni Marchetti, V.; Bitar, I.; Piazza, A.; Mercato, A.; Fogato, E.; Hrabak, J.; Migliavacca, R. Genomic Insight of VIM-harboring IncA Plasmid from a Clinical ST69 Escherichia coli Strain in Italy. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M.; Ramadan, H.; Sadek, M.; Nariya, H.; Shimamoto, T.; Hiott, L.M.; Frye, J.G.; Jackson, C.R.; Shimamoto, T. Draft genome sequence of a bla(NDM-1)- and bla(OXA-244)-carrying multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli D-ST69 clinical isolate from Egypt. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 832–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, A.M.; Hoffmann, M.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Abbas, N.H.; Yao, K.; Koenig, S.; Allué-Guardia, A.; Eppinger, M. Genomic features of colistin resistant Escherichia coli ST69 strain harboring mcr-1 on IncHI2 plasmid from raw milk cheese in Egypt. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 73, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.E.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Deng, H.; Liu, B.-T.; Fang, L.-X.; Liao, X.-P.; Liu, Y.-H. IncF plasmid diversity in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli strains from animals in China. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozzari, A.; Behzadi, P.; Kerishchi Khiabani, P.; Sholeh, M.; Sabokroo, N. Clinical cases, drug resistance, and virulence genes profiling in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Genet. 2020, 61, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Carattoli, A.; Karisik, E.; Underwood, A.; Ellington, M.J.; Livermore, D.M. Complete Nucleotide Sequences of Plasmids pEK204, pEK499, and pEK516, Encoding CTX-M Enzymes in Three Major Escherichia coli Lineages from the United Kingdom, All Belonging to the International O25:H4-ST131 Clone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4472–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, S.; Madec, J.Y.; Haenni, M. F2:A-:B- plasmid carrying the extended-spectrum β-lactamase bla(CTX-M-55/57) gene in Proteus mirabilis isolated from a primate. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 594–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, E.R.; Jones, A.M.; Hawkey, P.M. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: Temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2145–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Johnson, J.R.; Yamamoto, M.; Nagao, M.; Tanaka, M.; Takakura, S.; Ichiyama, S.; Komori, T.; Fujita, N.; Kyoto-Shiga Clinical Mi-crobiology Study Group. et al. CTX-M-27- and CTX-M-14-producing, ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli of the H 30 subclonal group within ST131 drive a Japanese regional ESBL epidemic. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1639–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, A.M.; Zweigner, J.; Wiese-Posselt, M.; Schwab, F.; Behnke, M.; Kola, A.; Schröder, W.; Peter, S.; Tacconelli, E.; Wille, T.; et al. Prevalence of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales colonization on hospital admission and ESBL genotype-specific risk factors: A cross-sectional study in six German university hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftode, I.-L.; Leca, D.; Miftode, R.-S.; Roşu, F.; Plesca, C.; Loghin, I.; Timpau, A.S.; Mitu, I.; Mititiuc, I.; Dorneanu, O.; et al. The Clash of the Titans: COVID-19, Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and First mcr-1-Mediated Colistin Resistance in Humans in Romania. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shein, A.M.S.; Wannigama, D.L.; Higgins, P.G.; Hurst, C.; Abe, S.; Hongsing, P.; Chantaravisoot, N.; Saethang, T.; Luk-In, S.; Liao, T.; et al. High prevalence of mgrB-mediated colistin resistance among carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with biofilm formation, and can be overcome by colistin-EDTA combination therapy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe—Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) 2016, Publications Office. 2017. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2900/296939 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Monaco, M.; Giani, T.; Raffone, M.; Arena, F.; Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Pollini, S.; Grundmann, H.; Pantosti, A.; Rossolini, G.M.; Network EuSCAPE-Italy. Colistin resistance superimposed to endemic carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A rapidly evolving problem in Italy, November 2013 to April 2014. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 20939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, S.G.; Bartolini, A.; Santacatterina, E.; Castellani, E.; Ghirardo, R.; Berto, A.; Franchin, E.; Menegotto, N.; De Canale, E.; Tommasini, T.; et al. Prevalence of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains producing carbapenemases and increase of resistance to colistin in an Italian teaching hospital from January 2012 to December 2014. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institutul Național de Sănătate Publică. CARMIAAM-ROM 2021 (Consumul de Antibiotice, Rezistența Microbiană și Infecții Asociate Asistenței Medicale în România—2021). Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/centrul-national-de-supraveghere-si-control-al-bolilor-transmisibile-cnscbt/analiza-date-supraveghere (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Institutul Național de Sănătate Publică. CARMIAAM-ROM 2019 (Consumul de Antibiotice, Rezistența Microbiană și Infecții Asociate Asistenței Medicale în România—2019). Available online: https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/analiza-date-supraveghere/infectii-nosocomiale-1/2704-consumul-de-antibiotice-rezistenta-microbiana-si-infectii-asociate-asistentei-medicale-in-romania-2019 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Cireșă, A.; Tălăpan, D.; Vasile, C.-C.; Popescu, C.; Popescu, G.-A. Evolution of Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae over 3 Years (2019–2021) in a Tertiary Hospital in Bucharest, Romania. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).