Abstract

The phylum Apicomplexa includes endoparasites of fish worldwide, which cause parasitic infections that can adversely affect productivity in aquaculture. They are considered bioindicators of water pollution. Piscine apicomplexan parasites can be divided into two major groups: the intracellular blood parasites (Adeleorina) and the coccidians (Eimeriorina), which can infect the gastrointestinal tract and several organs. This work aims to compile, as completely as possible and for the first time, the available information concerning the species of coccidia (Apicomplexa: Conoidasida), which has been reported from freshwater fish. A comprehensive bibliographic search was performed using all available databases and fields, including Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar. In the freshwater fish found, there were 173 described species. This review demonstrates that freshwater fish’s eimeriid coccidia are better studied than adeleid coccidia. Studies of coccidian freshwater fish fauna indicate a high infection with Eimeria and Goussia species. The wealthiest coccidia fauna were found in the Cypriniformes, Perciformes, Siluriformes and Cichliformes fishes.

1. Introduction

The phylum Apicomplexa (Levine et al., 1980) comprises a large group of obligate, intracellular protist parasites that are among the most prevalent and morbidity-causing pathogens worldwide. It includes endoparasites of fish worldwide and is responsible for diseases, which, in turn, may lead to economic and social impacts in different countries. Parasitic infections can adversely affect productivity in aquaculture, and they are considered bioindicators of water pollution. Clinical symptoms of coccidian infection in fish vary from asymptomatic to chronic signs of emaciation, anorexia, listlessness, whitish mucoid feces, abdominal distention, muscle atrophy, retarded growth and increased mortality, depending on the susceptibility of the fish species, fish age and size, cultured conditions, species of coccidia and degree of parasitic infection [1,2].

Freshwater fish are hosts for the many apicomplexan parasites. Apicomplexans have complex life cycles, and there is substantial variation among apicomplexan groups. Both asexual and sexual reproductions may be involved. The basic life cycle may be said to start when an infective stage, or sporozoite, enters a host cell and then divides repeatedly to form numerous merozoites. Apicomplexans are transmitted to new hosts in various ways; some are transmitted by infected invertebrates (leeches or another hematophagous arthropod), while others may be transmitted in the feces of an infected host or when a predator eats infected prey [3,4].

Piscine apicomplexan parasites can be divided into two major groups: the intracellular blood parasites (Adeleorina), which occur in host blood cells and the reticuloendothelial system, and the coccidian (Eimeriorina), which can infect the gastrointestinal tract and several organs.

Adeleorina parasites are currently distributed among six families. Three families of this were reported from fish: Dactylosomatidae (genus: Dactylosoma and Babesiosoma), Haemogregarinidae (genus: Haemogregarina, Cyrilia and Desseria), and Hepatozoidae (genus: Hepatozoon) (see Appendix A, Table A1).

The term “coccidia” has referred mainly to obligate intracellular protozoa of the genera Eimeria (Schneider, 1875) and Isospora (Schneider, 1881) in the family Eimeriidae, suborder Eimeriorina. According to Pugachev and Krylov, coccidia have been found in the fish, which belong to eight genera. Four genera of coccidia are described and found mainly in fish (Calyptospora, Crystallospora, Epieimeria, Goussia). Representatives of the other four genera (Cryptosporidium, Eimeria, Isospora, Octosporella) of coccidia parasitize not only fish but also different groups of vertebrates (see Appendix A, Table A1) [5,6,7,8,9].

This work aims to compile, as completely as possible and for the first time, the available information concerning the species of coccidia (Apicomplexa: Conoidasida) that have been reported in freshwater fish.

2. Study Design

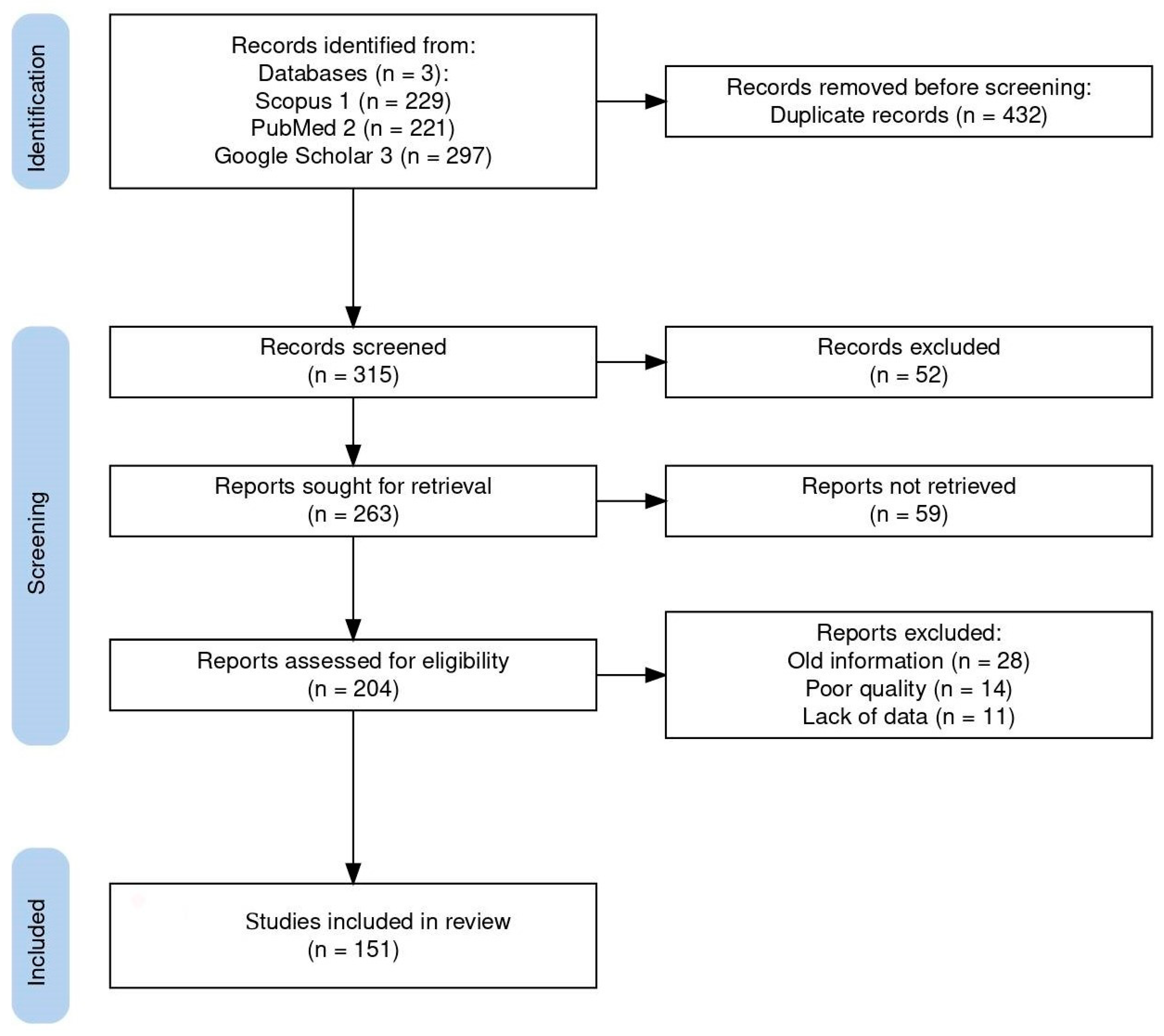

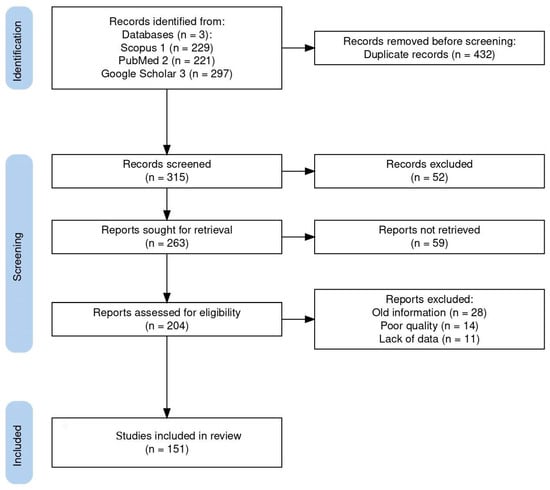

A comprehensive bibliographic search was performed using all available databases and fields included on Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar with the following search string: (Coccidia, Haemococcidia or Dactylosoma or Haemogregarine or Babesiosoma, or Hepatozoon or Cyrilia or Calyptospora or Cryptosporidium or Eimeria or Goussia or Isospora or Epieimeria or Crystallospora) and freshwater fish. Figure 1 illustrates the selection of studies employing the PRISMA flowchart [10]. The study looked for studies using PRISMA standards.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study design process showing the total number of retrieved reports, number of records after duplicates were removed, number of records screened and excluded, number of full-text articles assessed for eligibility, number of selected articles for analysis, and number of studies included in the review.

The systematic search used in this study initially turned up 747 documents. Of these articles, 432 were removed based on duplicate records, and 111 of the 315 screened records were disqualified due to their abstract and study similarities. A total of 204 full-length publications were assessed for eligibility, with 53 full-length articles being disqualified for a variety of reasons: old information (28), poor quality (14), and lack of data (11). Finally, 151 publications were included in the review. Here, we review the known best practices of search strategies and provide insight into how well the recent reviews and original research articles studied the top applied coccidians found in freshwater fish, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of our findings.

3. Adeleorina

3.1. Dactylosoma and Babesiosoma

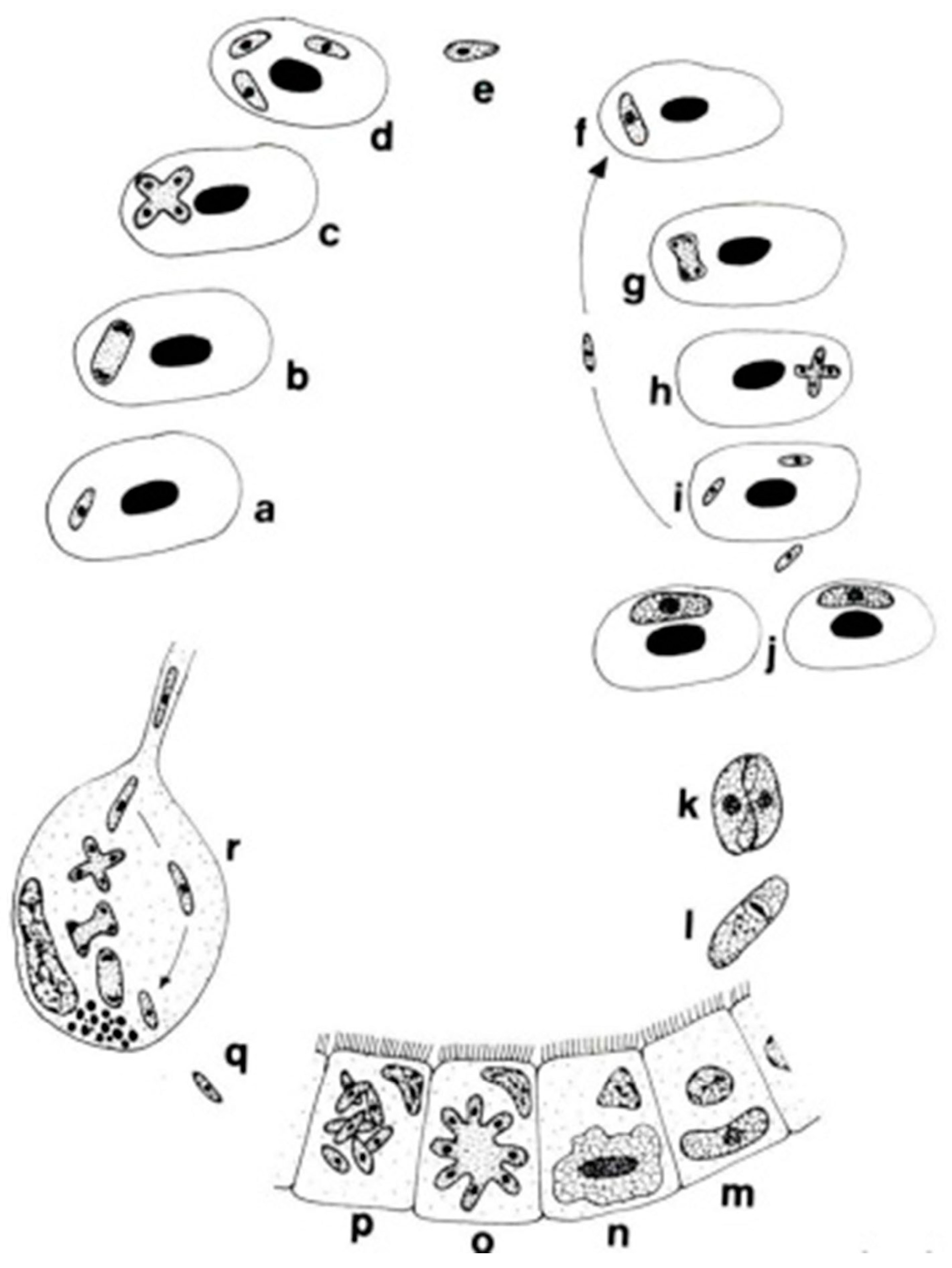

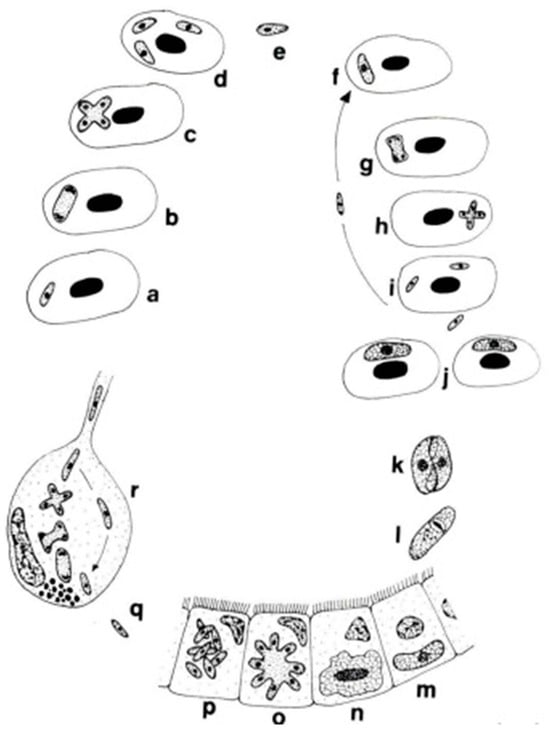

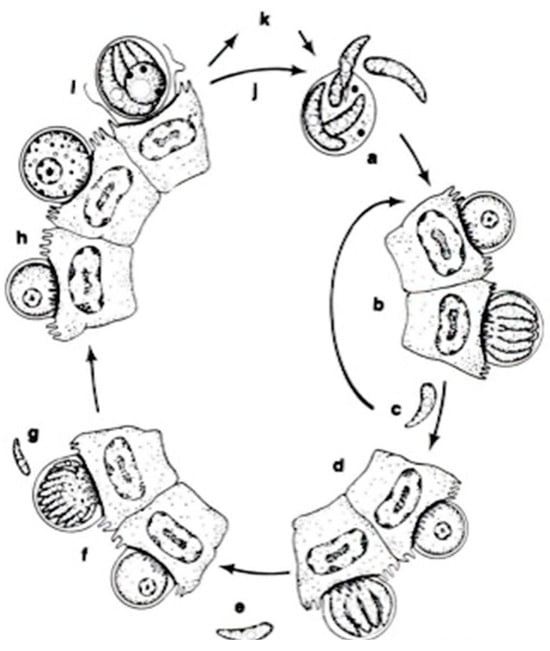

The genera Dactylosoma and Babesiosoma belong to the family Dactylosomatidae and include heteroxenous coccidians that cycle between two hosts: an invertebrate and a vertebrate host (Figure 2) [11,12,13].

Figure 2.

Life cycle of Babesiosoma stableri: a–e. Primary intraerythrocytic merogony; f–i. secondary merogony; j. gamonts; k–l. gamonts, freed in the blood meal, associate in syzygy, mature, and fuse to form a zygote; m. zygote (ookinete) penetrates the intestinal epithelial cells; n–p. sporogony forming eight naked sporozoites; q. migration of sporozoites to salivary cells; r. merogony in salivary cells produces numerous infective merozoites injected into the next host when the leech feeds (based on Barta and Desser, 1989) [14].

Members of the family Dactylosomatidae have remained, until recently, some of the most poorly understood members of the phylum Apicomplexa despite the long period that has elapsed since their discovery. Distinctive features between two dactylosomatid genera, Dactylosoma and Babesiosoma, were identified. However, these genera differ according to the number of merozoits (four merozoits in Babesiosoma, more than four in Dactylosoma) that formed in the erythrocytes of cold-blooded vertebrates [5,15]. In the definitive host, the number of sporozoites within oocysts of both genera is twice as much as the number of merozoites [13]. The fish host erythrocyte Babesiosoma differs from Dactylosoma in lacking a nuclear karyosome, possessing vacuolated and only slightly granular cytoplasm, and producing only four merozoites in a rosette or cross [16].

Several related species of this genus Dactylosoma were described from cichlids fish (species of Oreochromis, Astatorheochromis and Haplochromis) and grey mullets (Mugilidae—Mugil cephalus, Liza richardsoni, L. dumerili) in Africa throughout the first half of the XX century. The first species of Dactylosoma to be reported from fish was described by Hoare (1930) in Haplochromis spp. of Lake Victoria, Uganda, and named Dactylosoma mariae [17]. Jakowska & Nigrelli (1956) separated D. mariae Hoare, 1930 and placed them under the new genus Babesiosoma [15]. D. mariae = B. mariae Hoare, 1930; Baker, 1960 were found in Lakes Victoria and George, with a single record from O. mossambicus in Transvaal, South Africa. This parasite reported from the Okavango Delta (Botswana) produces four intraerythrocytic merozoites from cruciform meronts in the fish species Serranochromis angusticeps [18].

Dactylosoma hannesi (Paperna, 1981) was discovered in the blood erythrocytes of Mugil cephalus Flathead grey mullet), Chelon richardsonii (South African mullet) and C. dumerili (Grooved mullet) from Swartkops estuary, located east of Port Elizabeth, South Africa [19]. Recent studies indicate that D. hannesi is a Babesiosoma species, concluding that B. mariae and B. hannesi are synonymous [13,20].

The other species of the genus Dactylosoma to be recorded from fish is D. salvelini Fantham, Porter & Richardson (1942) from the Canadian trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) from the Province of Quebec, Canada. This species produced eight merozoites slightly smaller than D. mariae [21]. Sounders (1960) described D. lethrinorum from a Spangled emperor (Lethrinus nebulosus) and Pink ear emperor (L. lentjan) from the water of the Red Sea near Al Gardaga, Egypt [22].

All of these studies belong to the XX century. In recent years, two works have documented the presence of Dactylosoma in African regions [23,24].

Two additional dactylosomatid species from Indian fishes have been incorrectly assigned to the genus Dactylosoma. D. striata Sarkar and Haldar, 1979 and D. notopterae Kundu and Haldar, 1984 were described from the erythrocytes of freshwater teleosts [13,25]. Both species more closely resemble Babesiosoma species than Dactylosoma species, leading to the conclusion that D. striata, D. notopterae and B. ophicephali are synonymous [13].

As we noted, compared to species of Dactylosoma, species of Babesiosoma produce only four merozoites during each merogonic cycle and eight sporozoites within oocysts in the definitive host [13]. The Babesiosoma species described have a cosmopolitan distribution in marine and freshwater environments [13].

The first described Babesiosoma species was Babesiosoma mariae Hoare, 1930 (=B. hannesi Paperna, 1981). B. mariae were also detected from freshwater fish Chrysichthys auratus at Al Fath Center in Assiut Governorate, Egypt [26]. B. bettencourti França, 1908 (syn. Haemogregarina bettencourti França, 1908; Desseria bettencourti Siddall, 1995) were recorded from the erythrocytes the European eels, Anguilla anguilla L., captured in six rivers in northern and central Portugal [27]. B. tetragonis was observed in the erythrocytes of Catostomus sp. from the Shasta River north of California [28]. B. ophicephali and B. hereni are described from the red blood cells of the freshwater teleost fish Ophicephalus punctatus (=Channa punctatus (Spotted snakehead)), collected from the suburbs of Calcutta, West Bengal, India [29,30]. B. batrachi is described from the erythrocytes of a freshwater teleost fish, Clarias batrachus (Philippine catfish), from West Bengal, India [31]. B. rubrimarensis Saunders, 1960 was recorded from six specimens of fish (Lethrinus xanthochilu (Yellowlip emperor), L. variegatus (Slender emperor), Cephalopholis miniatus (Coral hind), C. hemistictus (Yellowfin hind), Scarus harid (Candelamoa parrotfish), Mugil troscheli = (Mugil poecilus (Largescale mullet)) from the water of the Red Sea near Al Gardaga, Egypt (see Appendix A, Table A2) [22].

In recent years, Babesiosoma sp. was recorded from two Egyptian freshwater fish species from the orders Cypriniformes and Siluriformes: Cyprius carpio (Common carp) and Clarias gariepinus (African catfish) [32] and three species from the order Cypriniformes of freshwater fish (Barbus grypus (Shabout), B. sharpeyi (Bunnei), Carasobarbus luteus (Yellow barbell) collected from the Khazar River in Ninevah Governorate, Iraq [33]. Babesiosoma sp. was also found in Cypriniformes fish—Triplophysa marmorata (Kashmir triplophysa-loach) from Anchar Lake and River Jhelum in Kashmir [34].

In conclusion, currently, there are five recognized species of Dactylosoma, two of which infect fish hosts, namely D. lethrinorum Saunders, 1960 and D. salvelini Fantham, Porter and Richardson, 1942 [24]. There are currently seven recognized species of Babesiosoma described from fish hosts, each with unique characteristics and adaptations. Five of them, namely B. mariae Hoare, 1930 or B. hannesi Paperna, 1981; B. tetragonis Becker and Katz, 1965; B. ophicephali Misra et al., 1969; B. hareni Haldar et al., 1971; and B. batrachi Haldar et al., 1971, have been recorded from freshwater fish (see Appendix A, Table A2).

3.2. Haemogregarina, Cyrilia, and Desseria

Haemogregarines are broadly distributed among vertebrate hosts, including fishes [6]. The development of haemogregarines is complex and occurs through two types of hosts: blood-sucking invertebrates (leeches) and vertebrates, including fish [4]. In haemogregarines, merogony and transformation of merozoites into gamonts occur in the blood cells of fish. In contrast, the differentiation of gamonts into gametes, zygote production and sporulation resulting in oocyst formation occur in leech vectors [5]. Oocysts of the genus Haemogregarina contain eight or more naked sporozoites [6].

Siddall (1995) placed fish haemogregarines in the genera Desseria Siddall, 1995 (41 species), Cyrilia Lainson, 1981 (1 species), and Haemogregarina Danilewsky, 1885 (sensu lato) (13 species) [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. They are commonly found in both erythrocytes and leukocytes of marine fishes, except for Cyrilia sp., which parasitize only the erythrocytes of freshwater fish [4]. Members of the three genera are differentiated by their development in vertebrate and invertebrate hosts. Cyrilia and Haemogregarina are both characterized by an intra-erythrocytic merogony phase in fish hosts, while in Desseria sp., this stage is not found [50]. The life cycles of a few fish haemogregarines are known, including Cyrilia, Desseria and some Haemogregarina sp.; they employ leeches as definitive hosts [49,51].

Haemogregarines were first recorded from the blood of marine fishes in France by Laveran and Mesnil (1901). They recorded Haemogregarina simondi in Dover sole, Solea solea (=Solea vulgaris), caught in the English Channel, and H. bigemina in blennies Lipophrys pholis (=Blennius pholis) and Corypho-blennius galerita (=Blennius montagui) (see Laveran and Mesnil, 1902) at Cap de la Hague in France (Davies, 1995). Most haemogregarines have been recorded from marine fish [4,52]. One of the most prevalent and cosmopolitan species of haemogregarines is H. bigemina, a marine fish parasite. H. bigemina Laveran et Mesnil, 1901 was recorded from 96 species of marine fishes across 70 genera and 34 families [50].

Wenyon (1908) was the first to describe a haemogregarine from a freshwater fish, H. nili from Ophiocephalus obscurus, in the Nile River, Egypt [35]. In 1923, Franchini and Saini described from perch (Perca fluviatilis) in France the species H. percae, along with three other new species from common freshwater fishes. It is estimated that some apicomplexans, out of 23 Haemogregarina species that are described in freshwater fish, are later placed in Cyrilia, Hepatozoon or other genera [4].

Other species that infect freshwater fish include H. catostomi, H. vltanensis, H. majeedin, and H. daviesensis: H. catostomi Becker 1962 occurred in largescale sucker (Catostomus macrochelius) and bridge lip sucker (C. columbianus), fishes of the central Columbia River [35,36]. H. vltavensis Lom et al., 1989 was observed from the red blood cells of the blood of perch (Perca fluviatilis) in southwestern Czechoslovakia [37]. H. majeedin Al-Salim, 1993 was reported and described from the heart blood film of the freshwater fish Bunnei (Barbus sharpeyi) captured in the Shalt al-Arab River, Basrah, Iraq [38]. H. daviesensis Esteves-Silva et al., 2019 is described from South American lungfish (Lepidosiren paradoxa) in the eastern Amazon region (see Appendix A, Table A2) [39].

H. cyprini Smirnoviç 1971 was reported from the blood of Cyprinus carpio (order Cypriniformes) in Iraq [40], H. meridianus Al-Salim, 1989 was described from the erythrocytes, erythroblasts and blood plasma of Planiliza abu (reported as L. abu) (order Mugiliformes) from the Shatt Al-Arab river [41]. H. acipenseris was recorded in the Siberian starlet (Acipenser ruthenus marsiglii) (order: Acipenseriformes) in the rivers of the Lower Irtysh basin [42]. This species lacked morphometric parameters.

Haemogregarina sp. was detected in the blood, liver, ovaries and kidneys of Glarias gariepinus (order: Siluriformes) in Sudan [43], in blood samples and the blood within the gill tissue of Oreochromis niloticus (order: Cichliformes) in Egypt [44] and in the erythrocytes of four specimens of freshwater Cypriniformes fish (Barbus grypus (Shabout), B. sharpeyi (Bunnei), Carasobarbus luteus (Yellow barbell)) and Mugiliformes fish (Liza abu (=Planiliza abu) (Abu mullet)) collected from the Khazar River in Ninevah Governorate, Iraq [33]. Intra-erythrocytic stages of Haemogregarina sp. were observed in Neoarius graffiti (Blue salmon catfish) (order: Siluriformes) sampled from the Brisbane River, Western Australia [45]. Haemogregarines are also found in the erythrocytes of the Kessler’s sculpin Leocottus kesslerii in Lake Baikal [46].

The genus Cyrilia was created in 1981. Species of Cyrilia infect freshwater fishes and are transmitted by the bite of African fish leeches, Batracobdelloides tricarinata. Hosts include the African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and Nile tilapia (Tilapia nilotica). The genus Cyrilia is of ecological interest, as it affects species such as Potamotrygon wallacei (Cururu stingray), found in the Amazon region, that help control the invertebrate population and act as bioindicators in environmental monitoring studies [47].

Lainson (1981) described Cyrilia gomesi parasitizing the freshwater swamp eel (Syngamus marmoratus) from Para State, North Brazil [53]. C. gomesi (Lainson 1981) was later amended to C. lignieresi (Lainson 1992) [6,53,54]. In previous work, Diniz et al. analyzed the ultrastructure of C. lignieresi trophozoites by transmission electron microscopy [7]. Some morphological characteristics of C. lignieresi have been described previously, but the parasite–erythrocyte relationship is still poorly understood [55]. Cyrilia sp. was recorded, and the trophozoites and all stages of gamonts were well described in the freshwater fish Cururu stingray from Rio Negro, a river of Amazonas, Brazil (see Appendix A, Table A2) [47].

The genus Desseria was described in 1995. All currently recognized species in this genus are infected fish. Species of Desseria were described very poorly; only vertebrate stages are known, and often, they are not described in detail. Some formerly known Deseria species are related to other genera [6,56,57]. Contemporary literature has insufficient information about Deseria. In 2021, Quraishy et al. suggested the family Haemogregarinidae, which contains the genera Haemogregarina and Cyrilia [58].

Many species of haemogregarines of fish are described in the old literature [4,21]. These works are problematic because of the tendency for brief or incomplete descriptions. For most of the first half of the XX century, there was a tendency to describe species of haemogregarines exclusively based on the intraerythrocytic gamont. Indeed, authors named new species for nearly every haemogregarine discovered in a novel host species or geographical location. By the middle of the XX century, several authors agreed that describing species based on these features or the structure of the bloodstream gamonts alone was specious [59]. For this reason, we prefer the new information about haemogregarines. Only one study using molecular tools to determine the species of haemogregarines in freshwater fish has been reported [58].

3.3. Hepatozoon

Hepatozoon is a genus of apicomplexan parasites known to cause musculoskeletal disease in numerous terrestrial vertebrate species whose life cycle involves sexual development (sporogony) in definitive hosts that are hematophagous arthropods (ticks, mites, lice and tsetse flies) and asexual development (merogony in visceral tissues; gamontogony in leukocytes) in a vertebrate host [59].

Species of Hepatozoon have been described from all groups of vertebrates, but their occurrence in fish is an infrequent phenomenon. Only two studies report the occurrence of parasites belonging to the Hepatozoon genus in fish [48,60]. Cysts containing Hepatozoon cystozoites were observed in the liver of Hoplias aimar (Poisson-tigre géant) (order: Characiformes) from the Eastern Amazon. This unique finding, the first report of the occurrence of cysts containing Hepatozoon cystozoites in free-living fishes, was confirmed by molecular analysis. The sequencing revealed that Hepatozoon sp. has identity with Hepatozoon caimani, detected in caimans (Caiman yacare) from Brazil [48]. Previously, it was experimentally demonstrated that Metynnis sp. fish are susceptible to H. caimans and develop numerous cysts morphologically similar to those described by Lainson et al. (2003). Metynnis sp. successfully transmitted H. caimans to caimans [60].

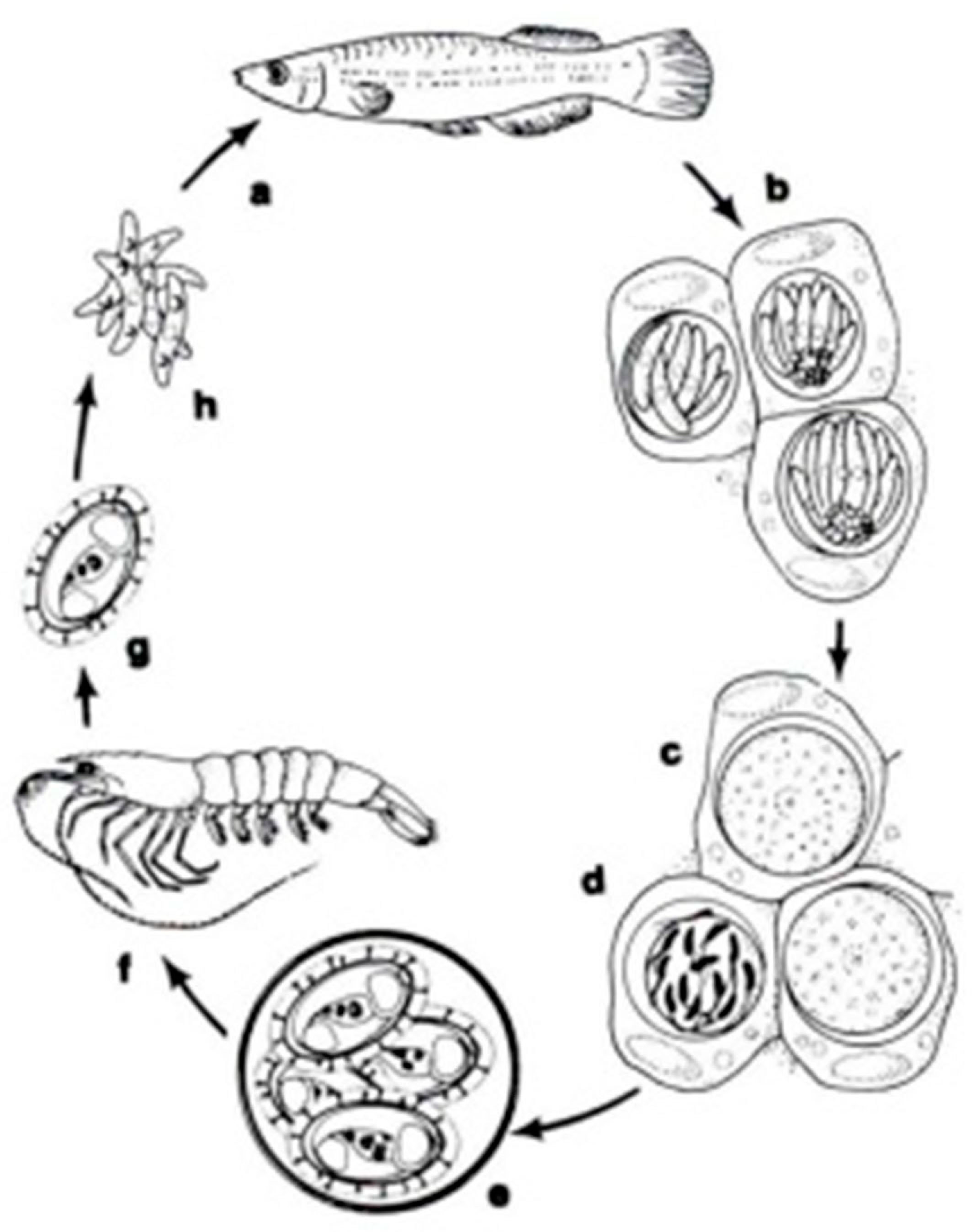

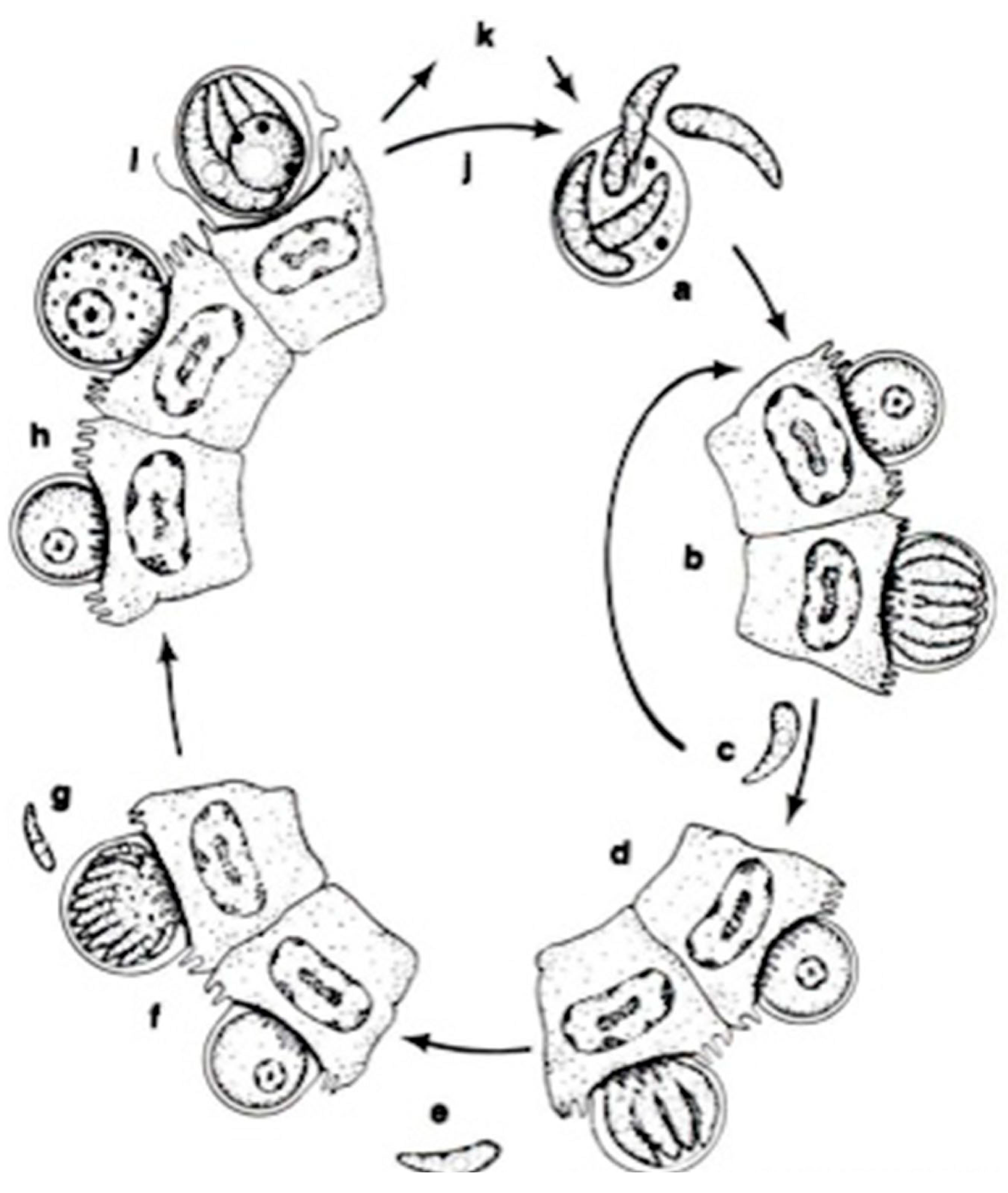

4. Eimeriorina

In a systematic respect, fish coccidia (Eimeriorina) have been studied much better than the intracellular blood parasites (Adeleorina). The life cycles of the coccidia that infect fish can be divided into two principal types—monogenic (the cycle occurs in one host; Cryptosporidium, Eimeria, Goussia, Isospora, Epieimeria, Crystallospora, and Octosporella) and heterogenic (involving both intermediate and paratenic hosts; Calyptospora) (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

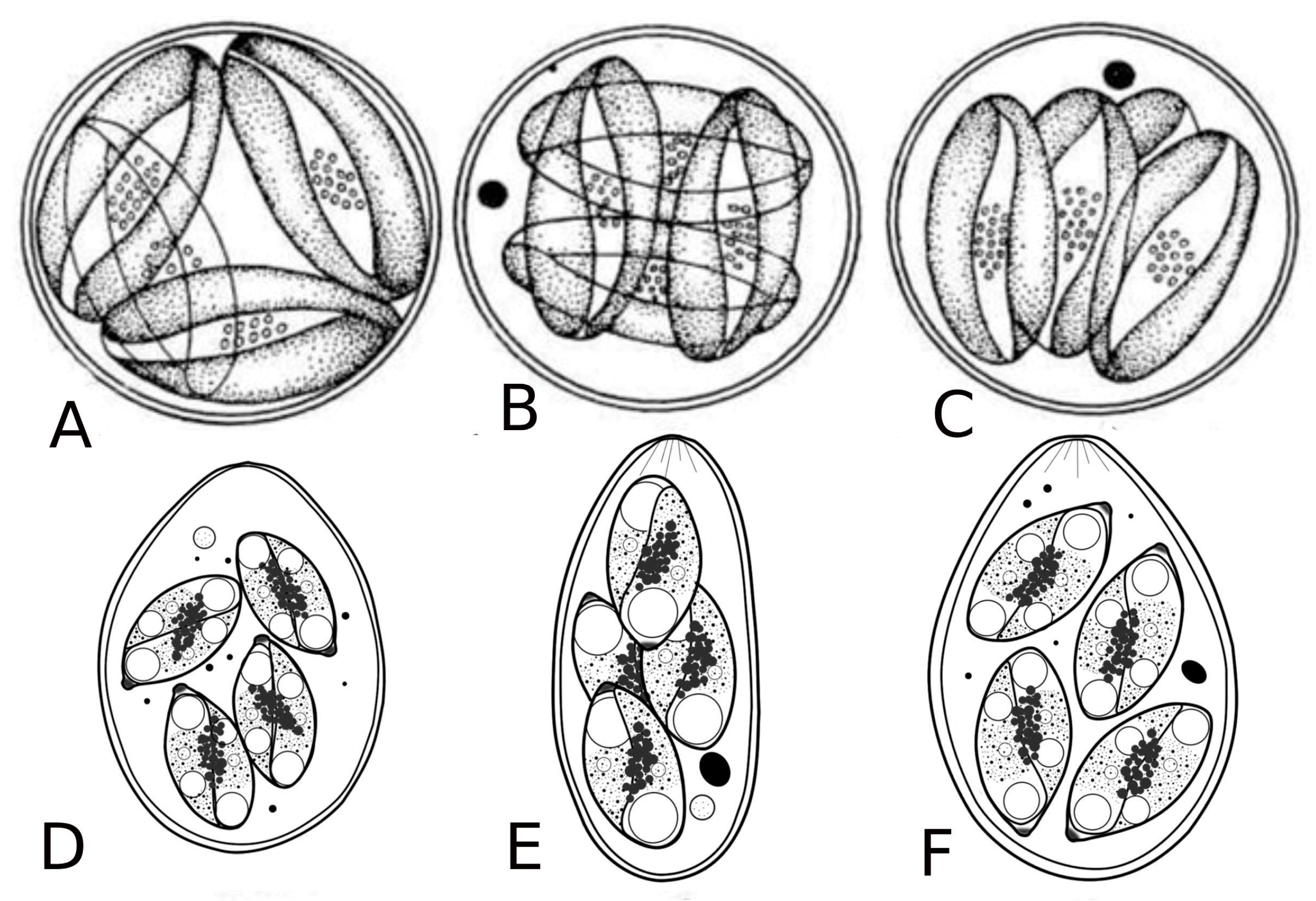

Figure 3.

The life cycle of Calyptospora funduli: a. sporozoites ingested along with shrimp by topminnows; b. sporozoites enter hepatocytes and undergo two generations of merogony: c. macrogametes and d. microgametocyte with microgametes; e. oocysts develop from zygotes and sporulate in situ; f. oocysts in the liver of decaying fish ingested by shrimp; g. liberation of sporocysts in the gut of shrimp; h. sporozoites enter the hepatopancreas and undergo a period of maturation [14].

Figure 4.

The life cycle of Cryptosporidium parvum: a. oocyst containing four sporozoites excysting in intestinal tract; b. type I meront; c. type I merozoites either recycle to produce additional type I meronts (b) or produce type II meronts; d. type II meront; e. type II merozoites penetrate new cells to form male and female gametes; f. microgametocyte; g. microgamete; h. macrogamete; i. sporulated oocyst in situ; j. thin-walled oocysts exocyst in situ (a) and infect new cells; k. thick-walled oocysts pass out in feces into the environment [14].

They parasitize different organs in vertebrate hosts. Oocysts of coccidian parasites were found in the epithelium of the gut, stomach, liver, kidney, spleen, gonads, gallbladder and feces [3]. The structure of oocysts and sporozoites is important for the taxonomy of these parasites (see Appendix A, Table A1) [5].

Coccidia in fish was first discovered and described 110 years ago. Several reviews on the regional and world fauna of coccidia of fishes were published during that period. Pellerdy (1974) and Dykova and Lom (1983) published the most significant reports on the world fauna of coccidia. Pellerdy (1974), in the monograph “Coccidia and Coccidiosis”, gives the names of 66 species of coccidia in infected fishes. Dykova and Lom (1983) described as many as 127 species of coccidia in fishes [3,61].

4.1. Calyptospora

The genus Calyptospora was erected in 1984 by Overstreet et al. to encompass species with sporocysts, without Stieda or sub-Stieda bodies, with a veil supported by sporopodia, and with an anterior apical opening [62]. The genus Calyptospora has heteroxenous life cycles involving fishes and shrimp. These intracellular protozoan parasites are found in the liver and intestine of their fish hosts. They have a heteroxenic life cycle transmitted by an infected crustacean (shrimp) ingested by a fish. In fish hosts, the oocysts (elliptical, oval or pear-shaped) present four sporocysts covered by a thin veil fixed by the presence of wall projections named sporopodia. Moreover, it presents a suture on the walls that does not divide the cell into two valves [63].

The first described species of Calyptospora was Calyptospora funduli, which lived in marine fishes [64]. The species diversity of Calyptospora is still poorly known; only six species included in the genus Calyptospora are described, especially fish parasitic parasites in the tropical Amazon region: C. serrasalmi Cheung, Nigrelli and Ruggieri, 1986 from piranha Serrasalmus niger and S. rhombeus [65,66]; C. tucunarensis Békési and Molnár, 1991 from tucunaré Cichla ocellaris [67]; C. spinosa Azevedo, Matos and Matos, 1993 from joaninha Crenicichla lepidota [68]; C. paranaidji Silva et al., 2019 from cichlid fish Cichla piquiti [69]; and C. gonzaguensis Silva et al., 2020 from Dusky Narrow Hatchetfish Triportheus angulatus [70]. Only one species—C. empristica Fournie et al., 1985—was described from the freshwater starhead topminnow, Fundulus notti, in southern Mississippi (North America) (see Appendix A, Table A3) [71].

There are also records of the parasitism of Calyptospora sp. in Brazilian freshwater fish—Arapaima gigas (Arapaima, Osteoglossiformes) [72], Triportheus guentheri and Tetragonopterus chalceus (both of Characiformes) [73], Brachyplatystoma vaillantii (Laulao catfish, Siluriformes) [74], Cichla temensis (Speckled pavon, Cichliformes) [75], and Aequidens plagiozonatus (Cichliformes) (see Appendix A, Table A3) [76].

4.2. Cryptosporidium

The apicomplexan parasite Cryptosporidium is a significant intestinal pathogen causing acute diarrheal disease in various vertebrates, including humans [77,78,79,80,81]. Its infections are not confined to a specific region, as they occur globally, and are emerging as a disease in both marine and freshwater fish in numerous countries. Cryptosporidium species have been reported in 23 freshwater and 24 marine fish species [82], highlighting the global prevalence of this zoonotic risk. Detecting the protozoa in fish is a reliable indicator of environmental contamination or ecosystem health, suggesting a potential environmental source of human exposure and infection. The parasite is transmitted through various routes, including ingesting contaminated food or water, person-to-person contact, contact with animals, and recreational water, all contributing to the fecal–oral contamination route [83].

Cryptosporidium has some features that differentiate them from all other Coccidia, including (1) intracellular and extra-cytoplasmic localization, (2) forming of a “feeder” organ, (3) presence of morphological (thin- or thick-walled) oocysts as well as functional (auto vs. new infection) types of oocysts, (4) small size of oocysts, (5) missing some morphological characteristics, such as sporocysts or micropyles, and (6) the resistance of Cryptosporidium to all the available anti-coccidial drugs [84].

The traditional classification of Cryptosporidium within the coccidians has now been securely rejected based on comparative ultrastructural and genomic data. Based on recent genetic analyses, Cryptosporidium is no longer considered a coccidian and has been reclassified as a gregarine within the subclass Cryptogregaria. Like the gregarines, Cryptosporidium exhibits plasticity in its life cycle and options for parasitism, including the ability to multiply without host cell encapsulation. Different reports have supported the similarities between Cryptosporidium and gregarines. However, the position of the genus Cryptosporidium on the evolutionary tree of Apicomplexa is unresolved [85,86,87].

In contrast with the epicellular location of Cryptosporidium species from other vertebrates, in the case of piscine Cryptosporidium species, sporulation occurs deep within the epithelium in the piscine Cryptosporidium species [88,89,90].

The environmental stage, the oocyst, is environmentally robust, and there are few distinguishing morphological features; therefore, molecular characterization is required to delimit species. Currently, 44 species of Cryptosporidium are recognized based on molecular and biological criteria [91]. Five species of them have been genetically described in fish as a specific host: C. molnari Álvarez-Pellitero & Sitjà-Bobadilla 2002, C. scophthalmi Álvarez-Pellitero et al., 2004, C. huwii Ryan et al., 2015, C. bollandi Bolland et al., 2020 and C. abrahamseni Zahedi et al., 2021 [82].

The first piscine host of Cryptosporidium found was the tropical marine fish Naso lituratus, in which C. nasorum was identified by Hoover in 1981 (see [92]). After the first description, different histological studies reported developmental stages of Cryptosporidium in several marine and freshwater fish species’ stomachs and intestines [2]. The first report on Cryptosporidium of freshwater fish was published in 1983 [92]. Currently, the following three species are recognized as specific to freshwater fish hosts: C. huwii from guppy (Poecilia reticulata), golden tiger barb (Puntigrus tetrazona) and neon tetra (Paracheirodon innesi) [89,93,94]; C. bollandi from angelfish (Pterophyllum scalare) and Oscar fish (Astronotus ocellatus) (Bolland et al., 2020); and C. abrahamseni from red-eye tetras (Moenkhausia sanctaefilomenae) [95].

C. molnari and C. scophthalmi are described from marine fish [88,96,97]. Some freshwater fish species have been reported as other natural hosts for C. molnari (see Appendix A, Table A4) [98,99,100,101,102].

Cryptosporidium species found in other groups of vertebrates have also been identified in freshwater fish: C. parvum, C. hominis and rat genotype III [100,101,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112]. Current knowledge of the epidemiology, taxonomy, pathology and host specificity of Cryptosporidium species infecting piscine hosts is higher than in previous years. Furthermore, many different genotypes and Cryptosporidium sp. have been identified in fish (see Appendix A, Table A4).

4.3. Eimeria, Goussia, Isospora, Octosporella

The Coccidia genus, which contains many species that infect a wide variety of fish, reptiles, birds and mammals, is a fascinating area of study due to its host-specific nature [113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122]. Almost all species are specific to a particular host. The life cycle of Eimeria and all other species is considered monoxenous, meaning that the cycle occurs in one host. The life cycle of the specimens of this genus has two distinct stages: the exogenous phase (sporogony) and the endogenous phase (schizogony and gametogony). Fish Eimeria species differ from typical Eimeria species from higher vertebrates in having, as a rule, a thin oocyst wall and endogenous sporulation [123].

In the Eimeria genus, four sporocysts develop within the circumplasm of the oocyst, each containing two banana-shaped sporozoites. The genus Goussia was erected to accommodate piscine coccidians with oocysts possessing four sporocysts, with two valves joined by a longitudinal suture. Eimeria and Goussia of freshwater fishes from various parts of the world have been studied relatively well (see Appendix A, Table A5 and Table A6). Table A5 lists 88 species of the Eimeria, and Table A6 lists 52 of the Goussia reported from freshwater fish.

Significant findings have been made in recent years in studying coccidians in various fish species. Eimeria sp. was recorded from the freshwater fish Liza abu = Planiliza abu (Abu mullet) obtained from Tigers River in Mosul city, Iraq [118]. In the last years, Eimeria sp. and Isospora sp. were recorded in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in Upper Egypt [124].

Eimeria species were detected in Siluriformes fish—Clarias gariepinus and Heteroclarias species from some selected fish farms in Kaduna state, Nigeria [125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135]—Astronotus ocellatus (Oscar, Cichliformes) and Cypriniformes fish—Carassius auratus (Goldfish) Puntius conchonius (Rosy barb) in Iran [120].

Most of the species reported in freshwater fish belong to Eimeria and Goussia, and only a handful belong to the genera Isospora, Epieimeria, Crystallospora and Octosporella. Only two freshwater fish species have been found—Isosopa lotae Belova, Krylov, 2001 and I. sinensis Chen, 1984. Three species of the genus Octosporella have been described from Cyprinid fish from Lake Sasajewun and Lake Opeongo, Algonquin Park, Ontario, North America [136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145] (see Appendix A, Table A5, Table A6 and Table A7). More information about Octosporella species in fish needs to be provided in the latest literature. Epieimeria and Crystallospora species have been recorded in marine fish [146].

5. Distribution of Coccidian Freshwater Fish

5.1. Distribution of Coccidia by Order of Freshwater Fish

Fish species worldwide are classified into 93 orders [147]. Our search identified 200 defined and undefined species of adeleid and eimeriid coccidians distributed among 11 genera and found in representatives of only 22 orders of freshwater fish: Dactylosoma, Babesiosoma, Haemogregarina, Cyrilia, Hepatozoon, Calyptospora, Cryptosporidium, Eimeria, Goussia, Isospora and Octosporella (see Appendix A, Table A8).

In freshwater fish, 173 described species have been identified: Cyrilia and Hepatozoon, each with one described species; Dactylosoma and Isospora, both with two described species; Octosporella, with three described species; Babesiosoma, with five described species; Cryptosporidium, with six described species (four specific to piscine hosts and two specific to mammals); Calyptospora, with six described species; Haemogregarina, with seven described species; Goussia, with 52 described species; and Eimeria, with 88 described species (see Appendix A, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6 and Table A7).

For some species, obtaining information regarding the characteristics considered in this review was not possible. Most of the descriptions of Eimeria, Goussia, Calyptospora, Octosporella and Isospora species have relied only on the morphology of oocysts and their location in the hosts. Although fish coccidians began to be described more than one century ago, genetic data on fish coccidians have only started to be collected since the 2010s [105,141,148]. Genetic data are mainly missing for piscine Coccidia (freshwater and marine), except for Cryptosporidium species [149,150].

In the representatives of the order Cypriniformes, Perciformes, Cichliformes, Siluriformes, Salmoniformes, Characiformes, Cyprinodontiformes, Asipenceriformes, Anabantiformes, Eupercaria and Mugiliformes, both adeleid and eimeriid coccidia have been found. In the orders Ceradontiformes, Synbranchiformes and Myliobatiformes, adeleid coccida have been found; and in fishes of the order Cyprindontiformes, Esociformes, Centarchiformes, Gobiiformes, Gymnotiformes, Osmeriformes, Beloniformes, Gadiformes and Osteoglossiformes, only eimeriid coccidia have been described. Representatives of these orders are characterized by low abundance and few species (see Appendix A, Table A8). From our point of view, this circumstance explains their absence in the description of coccidia.

The wealthiest coccidia fauna were found in the Cypriniformes, Cichliformes Siluriformes and Perciformes fish. Thus, coccidia belonging to seven genera (Babesiosoma, Haemogregarina, Cryptosporidium, Eimeria, Goussia, Isospora and Octosporella) were found in fishes of the order Cypriniformes. Six genera of coccidia (Babesiosoma, Haemogregarina, Calyptospora, Cryptosporidium, Eimeria and Isospora) were described in fishes of the order Cichliformes, and the same number of genera were represented in fishes of the order Siluriformes (Babesiosoma, Haemogregarina, Calyptospora, Cryptosporidium, Eimeria and Goussia). Coccidia belonging to three genera have been described as representatives of three orders: Perciformes, Charasiformes and Mugiliformes. In the five orders (Salmoniformes, Cyrinidontiformes, Centarchiformes, Anabantiformes, Asipenceriformes), coccidia were found belonging to three genera. In the remaining 11 orders (Esociformes, Gobiiformes, Eupercaria, Gymnotiformes, Osmeriformes, Gadiformes, Ceradontiformes, Osteoglossiformes, Beloniformes, Synbranchiformes, Myliobatiformes), coccidia were found belonging to either one or two genera (see Appendix A, Table A8).

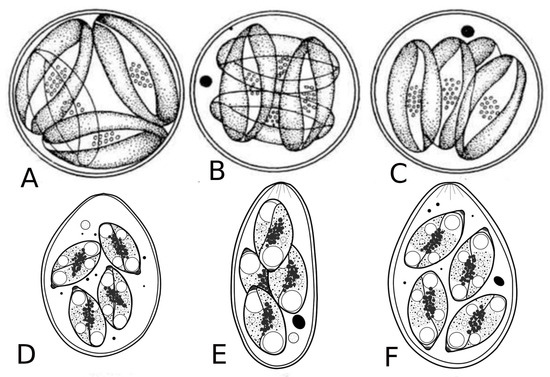

The results of the analysis of various taxonomic groups of coccidia in fishes have appeared rather attractive. Coccidia of the genera Cryptosporidium, Eimeria and Goussia were found in fishes most frequently (Figure 5). Cryptosporidium species were found in different groups of coccidians, especially in the orders Cypriniformes and Chichliformes. Most Eimeria and Goussia species were found in the orders Cypriniformes and Perciformes [151,152]. The genera Dactylosoma, Cyrilia, Hepatozoon, Isospora and Octosporella have limited fish distribution. Coccidia of the genera Hepatozoon occurred only in Characiformes and Octosporella, only in Cypriniformes (see Appendix A, Table A9 and Table A10).

Figure 5.

Oocysts of coccidia of freshwater fish. A, B, C—oocysts of Goussia; D, E, F—oocysts of Eimeria [9].

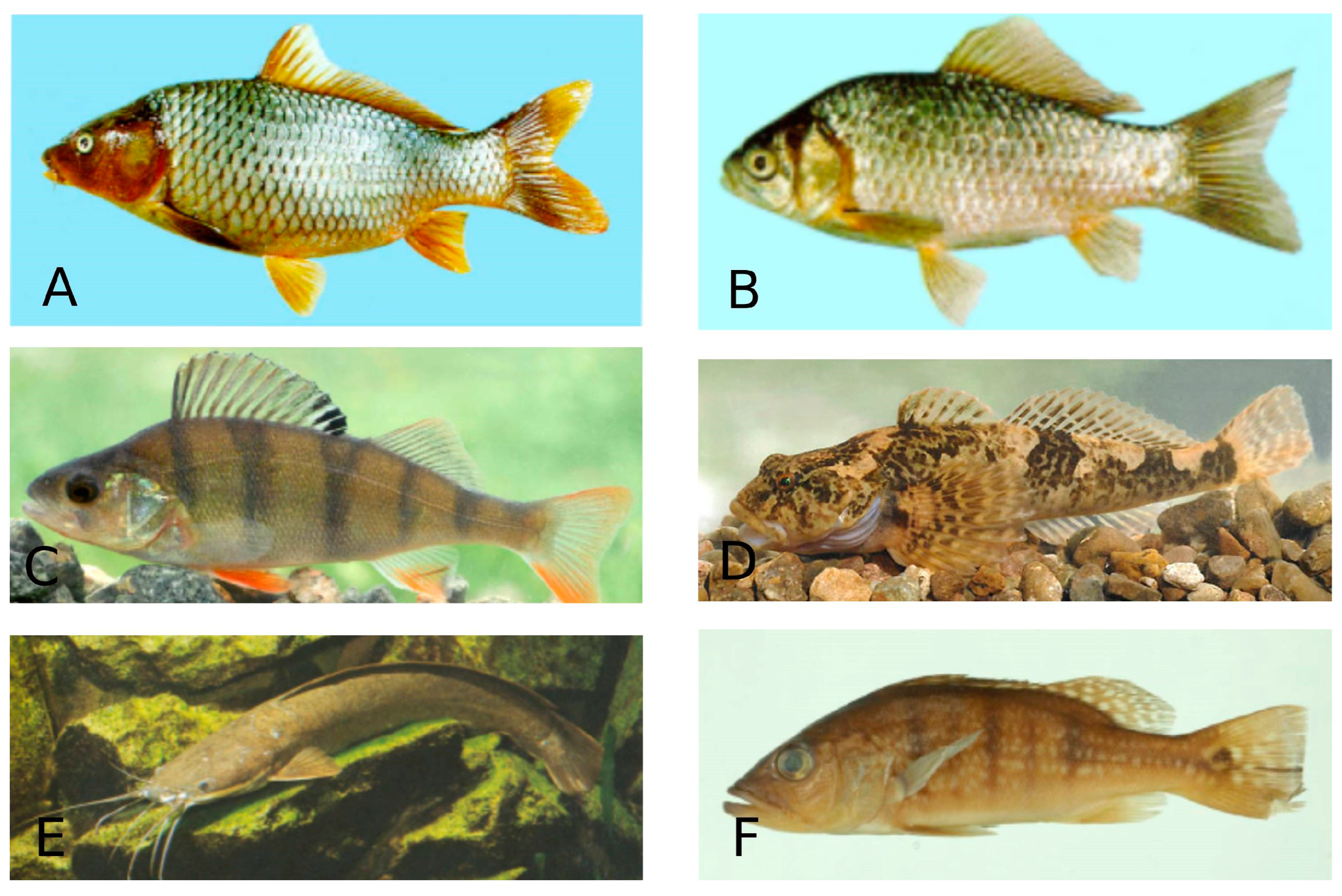

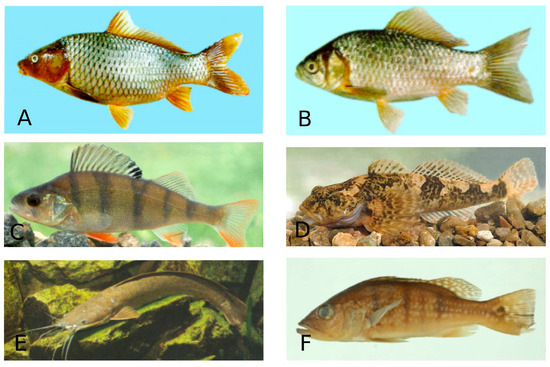

Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and Goldfish (Carassius auratus) in the order Cypriniformes, European perch (Perca fluviatilis) and Bullhead (Cottus gobio) in the order Perciformes, North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) in the order Siluriformes and Peacock cichlid (Cichla ocellaris) in the order Chichliformes were the most infected fish species (Figure 6). The distribution of systematic groups of coccidia by fish order and fish species is apparently determined by two main factors: the first is the quantitative and qualitative composition of fish orders, and the second is the intensity of the survey.

Figure 6.

Species of freshwater fish. A—Cyprinus carpio (Common carp)—Cypriniformes; B—Carassius auratus (Goldfish)—Cypriniformes; C—Perca fluviatilis (European perch—Perciformes; D—Cottus gobio (Bullhead)—Perciformes; E—Clarias gariepinus (North African catfish)—Siluriformes; F—Cichla ocellaris (Peacock cichlid)—Chichliformes. (Fish species numbers in the FishBase classification list, Available online: https://www.fishbase.se/tools/Classification/ClassificationList.php, accessed on 3 February 2025).

5.2. Distribution of Coccidian Freshwater Fish by Continent

Current knowledge on the geographic distribution of freshwater fish adeleid coccidia is limited. Most species of the genus Babesisoma have been reported from Asia and Africa. Haemogregarine infections of freshwater fish occurred in all continents. Asia is the primary source of information concerning the haemogregarine infection of freshwater fish. Little information has been published about Dactylosoma, Cyrilia and Hepatozoon infection of freshwater fish in Africa and South America (see Appendix A, Table A8).

Eimeriid coccidia has a more prevalent geographical distribution in freshwater fish than adeleid coccidia. The species of Eimeria and Goussia are widespread all over the world. All continents except South America have had descriptions of them. Most species of Eimeria and Goussia have been reported from Eurasia and North America; a significant fraction have also been reported from South America, Africa and Australia (see Appendix A, Table A9 and Table A10).

Cryptosporidium infections of freshwater fish have been documented from all continents. Almost all described species of Cryptosporidium, and the vast majority of them, have been reported from Australia. A significant percentage of Cryptosporidium infections in freshwater have been reported in Eurasia. There is a lack of knowledge about Cryptosporidium infections in freshwater fish in America and Africa (see Appendix A, Table A9 and Table A10).

All species of Calyptospora and Octosporella of freshwater fish have been reported from South America (Amazon) and North America, respectively. Little information is available about Isospora infection of freshwater fish in Eurasia and Africa (see Appendix A, Table A9 and Table A10).

6. Conclusions

This review demonstrated that freshwater fish’s eimeriid coccidia are better studied than the adeleid coccidia of freshwater fish. Studies of the coccidian fauna of freshwater fish indicate that infection is highly prevalent among the Eimeria and Goussia species. The wealthiest coccidia fauna were found in the families of valuable commercial fish such as Cypriniformes, Perciformes, Siluriformes and Cichliformes fish. Fish coccidiosis is an essential and most prevalent protozoan parasitic disease that affects fish economic loss in aquaculture due to the morbidity and mortality rates reported in some fish species. For the control and prevention of fish coccidiosis, proper hygienic and bio-security measures should be implemented to remove the coccidia oocysts from aquaculture facilities, where fish cohabit in dense groups and are subjected to other stress factors that can enhance the transmission of these parasites.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception of the study. S.M.: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing—review and editing. P.K.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Supervision of the whole process. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Classification and main morphologic characteristics of the genera of Apicomplexa described in fish hosts.

Table A1.

Classification and main morphologic characteristics of the genera of Apicomplexa described in fish hosts.

| Class | Subclass | Order | Suborder | Family | Genus | Main Morphological Characteristics |

| Conoidasida Levine, 1988 | Coccidia Leuckart, 1879 | Eucoccidiorida Leger, 1911 | Adeleorina Leger, 1911 | Dactylosomatidae Jakowska & Nigrelli, 1955 emend. Levine, 1971 | Dactylosoma Labbe 1894 | Merogony produced 3 to 8 merozoites in erythrocytes, often in a fan-like arrangement [5]. |

| Babesiosoma Jakowska & Nigrelli, 1956 | Merogony produced not more than 4 merozoites in rosettes or a cross-shaped arrangement [5]. | |||||

| Haemogregarinidae Leger, 1911 | Haemogregarina Danilewsky, 1885 | Gamonts are elongate or crescent-shaped, frequently with one end tapered and the other rounded, and are often as long as erythrocytes. Meronts in the erythrocytes or leucocytes are rounded or worm-like, and each meront can produce 2–36 oval to crescent-shaped merozoites. Oocysts of the genus Haemogregarina contain eight or more naked sporozoites [6]. | ||||

| Cyrilia, Lainson, 1981 | Vermicular meronts in vertebrate erythrocytes. Sporogony intracellular in leech (Glossiphoniidae) intestinal epithelial cells, acystic, single sporogonic germinal center producing more than 16 sporozoites [6]; oocysts of the genus Cyrilia contain 20–30 sporozoites [7]. | |||||

| Desseria, Siddall, 1995 | Lack of erythrocytic merogony. Gametogenesis and sporogony intracellular in the leech (Piscicolidae) intestinal epithelial cells; microgametogenesis producing 4 aflagellate microgametes; sporogony acystic, single sporogonic germinal center producing more than 16 sporozoites [6]. | |||||

| Hepatozoidae Wenyon, 1926 | Hepatozoon, Miller, 1980 | Gamonts are enveloped in a thick membrane and are often situated in the centre of the neutrophil and compress its lobulated nucleus toward the cell membrane. Produce enormous oocysts with numerous sporocysts, each with 4, 16 or more sporozoites [6]. | ||||

| Eimeriorina Leger, 1911 | Calyptosporidae Overstreet, Hawkins & Fournie, 1984 | Calyptospora Overstreet, Hawkins & Fournie, 1984 | Oocysts with 4 sporocysts, each with 2 sporozoites; sporocysts with sporopodia [8]. | |||

| Cryptosporidiidae Leger, 1911 | Cryptosporidium Tyzzer, 1907 | Oocyst with four sporozoites [8]. | ||||

| Eimeriidae Minchin, 1903 | Eimeria Schneider, 1875 | Oocysts with 4 sporocysts, each with 2 sporozoites, merogony intracellular [8]. | ||||

| Goussia Labbe, 1896 | Oocysts with 4 sporocysts, each with 2 sporozoites; dehiscence suture longitudinal [8]. | |||||

| Isospora Schneider, 1875 | Oocysts with two sporocysts, each with 4 sporozoites [8]. | |||||

| Epieimeria Dykov & Lom, 1981 | Oocysts with 4 sporocysts, each with 2 sporozoites, merogony and gamogony extracellular; sporogony intracellular [8]. | |||||

| Crystallospora Labbe, 1896 | Oocysts with 4 sporocysts, each with 2 sporozoites; sporocysts resemble crystals [8]. | |||||

| Octosporella Ray & Ragavachari, 1942 | Oocysts with 8 sporocysts, each with 2 sporozoites [8]. |

Table A2.

Dactylosoma, Babesiosoma, Haemogregarina, Cyrilia and Hepatozoon species currently recognized in freshwater hosts, along with their morphometric parameters.

Table A2.

Dactylosoma, Babesiosoma, Haemogregarina, Cyrilia and Hepatozoon species currently recognized in freshwater hosts, along with their morphometric parameters.

| Species | Type Host | Type Locality | Morphometric Parameters | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dactylosoma salvelini Fantham, Porter & Richardson, 1942 | Salvelinus fontinalis (Brook trout)—Salmoniformes | North America (Canada) | Secondary merogony: Meronts: 5.8–8.5 × 3.7–7.0 Gamonts: 4.4–7.8 × 1.5–3.0 | [21] |

| Dactylosoma lethrinorum Saunders, 1960 | Lethrinus nebulosus (Spangled emperor), L. lentjan (Pink ear emperor)—Eupercaria | Africa (Red Sea (Egypt)) | Meronts: 8.0 × 10.5 Merozoties: 1.9 × 2.4 | [22] |

| Babesiosoma mariae—Hoare, 1930; Baker, 1960 (syns: Dactylosoma mariae, Babesiosoma hannesi Paperna, 1981) | Haplochromis nubilus (Blue Victoria mouthbrooder), H. cinereus, H. serranus and H. sp. (Teleostei), Oreochromis esculentus (Singida tilapia), Serranochromis angusticeps (Thinface largemouth tilapia)—Cichliformes | South Africa | Merozoites: 2.8 × 0.9 Trophozoites: 3.8–5.7 × 1.9–5.0 Gamonts: 6.6–8.5 × 1.9–3.5 (Crescent); 5.7–6.6 × 3.8–5.7 (Rounded) | [17,18] |

| Mugil cephalus (Flathead grey mullet), Chelon richardsonii (South African mullet), C. dumerili (Grooved mullet)—Mugiliformes. | South Africa | Merozoites: 2.9 ± 0.2 × 0.4 Trophozoites: 3.8 ± 0.5 × 1.2 ± 0.1 Meronts: 3.8 × 1.4 (with 2 nuclei); 3.8 × 3.5 (with 4–8 nuclei) | [19] | |

| Chrysichthys auratus (Golden Nile catfish)—Siluriformes | Africa (Egypt) | Meront: 4.8 × 5.5 Meront: 4.2–4.5 × 4.5–4.9 (Cruciform) Merozoites: 2.2–2.6 × 2.8–4.0 Gamonts: 2.0–2.2 × 4.7–5.7 (Micro); 2.8 × 7.2 (Macro) | [26] | |

| Babesiosoma tetragonis Becker & Katz, 1965 | Catostomus sp.—Cypriniformes | North America (California, US) | Trophozoites: 2.2–3.7 × 4.4–6.6 (Elliptical); 3.3–4.8 × 3.8–5.5 (Oval) Meronts: 3.0–3.9 × 5.5–6.7 (Tetranueleate); 5.5–6.9 × 5.8–7.4 (Cruciform) Merozoites: 1.4–2.6 × 2.6–5.3 Gamonts: 3.0–4.8 × 6.1–8.2 (Macro); 1.6–2.8 × 4.9–7.2 (Micro) Extracellular merozoites: 1.5–3.1 × 2.3–3.4 | [28] |

| Babesiosoma ophicephali Misra et al., 1969 (syns: Dactylosoma striata Sarkar & Haldar, 1979 & D. notopterae Kundu & Haldar, 1984) | Ophicephalus punctatus = Channa punctatus (Spotted snakehead), O. striatus = C. striatus (Striped snakehead)—Anabantiformes; | Asia (West Bengal, India) | Youngest forms: 2.0 × 3.0 Trophozoites: 2.0–2.5 × 3.5–6 Schizonts: 2.5 × 4.0 Macrogametocyte: 2.5 × 3.5 Microgametocyte: 1.5 × 5.0 | [29] |

| Babesiosoma hareni Haldar et al., 1971 | Ophicephalus punctatus = Channa punctatus (Spotted snakehead)—Anabantiformes | Asia (West Bengal, India) | Youngest forms: 1.5 × 2.0 Trophozoites: 1.5 × 2.5 Schizonts: 3.0 × 3.5 Macrogametocyte: 2.5 × 2.5 Microgametocyte: 1.5–2.5 × 5.0–6.5 | [30] |

| Babesiosoma batrachi Chaudhuri & Choudhury, 1983 | Clarias batrachus (Philippine catfish)—Siluriformes | Asia (West Bengal, India) | Youngest forms: 1.6 × 1.75 Trophozoites: 3.0 × 5.0 Schizonts: 4.0 × 4.5 Macrogametocyte: 1.7 × 1.7 Microgametocyte: 2.4 × 5.8 | [31] |

| Babesiosoma sp. | Cyprius carpio (Common carp)—Cypriniformes; Clarias gariepinus (African catfish)—Siluriformes | Africa (Nile river) | [32] | |

| Barbus grypus (Shabout), Barbus sharpeyi (Bunnei), Carasobarbus luteus (Yellow barbell)—Cypriniformes | Asia (Iraq) | [33] | ||

| Triplophysa marmorata (Kashmir triplophysa-loach)—Cypriniformes | Asia (Kashmir) | Cruciform meronts: 4.3 ± 0.58 × 5.3 ± 0.58 Merozoites: 2.7 ± 0.5 × 3.0 ± 0.82 Gamonts: 3.1 ± 0.47 × 5.3 ± 0.64 | [34] | |

| Haemogregarina catostomi Becker, 1962 | Catostomus macrochelius (Largescale sucker), C.columbianus (Bridgelip sucker)—Cypriniformes | North America (USA, Washington state) | Qametosytes: 4.57 (3.52–6.32 × 14.5 (12.08–16.48) Nucleus: 3.37 (1.87–4.48) × 4.1 (2.32–6.24) | [35,36] |

| Haemogregarina vltavensis Lom et al., 1989 | Perca fluviatilis (European perch)—Perciformes | Europe (Czechoslovakia) | Intra-erythrocytic gametocytes: 10 × 22 Nucleus: 2.0 × 4.1 Mature gametocytes: 3.4 (2.2–4 0.9) × 12.5 (9.7–5.4) Free gametocytes: 3.1 (2.1–4 0.1) × 14.8 (12.0–16 0.9) | [37] |

| Haemogregarina majeedi Al-Salim, 1993 | Barbus sharpeyi (Bunnei)—Cypriniformes | Asia (Shalt al Arab river, Basrah, Iraq) | Merozoites: 0.7 × 4.2 Nucleus: 0.7 × 0.7 Free merozoites: 2.5 × 7.0 Mature gametocytes: 0.9–2.1 × 11.7–12.0 | [38] |

| Haemogregarina daviesensis Esteves-Silva et al., 2019 | Lepidosiren paradoxa (South American lungfish)—Ceratodontiformes | South America (Eastern Amazon region) | Qametosytes: 6 ± 0.97 (5–8) × 16 ± 0.12 (13–18) | [39] |

| Haemogregarina cyprini Smirnoviç 1971 | Cyprius carpio (Common carp)—Cypriniformes | Asia (Iraq) | [40] | |

| Haemogregarina meridianus Al-Salim, 1989 | Planiliza abu (Abu mullet)—Mugiliformes | Asia (Iraq) | [41] | |

| Haemogregarina acipenseris Nawrotzky, 1914 | Acipenser ruthenus marsiglii (Siberian starlet)—Acipenseriformes | Asia (Irtysh river) | [42] | |

| Haemogregarina sp. | Glarias gariepinus (North African catfish)—Siluriformes | Africa (Sudan) | [43] | |

| Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia)—Cichliformes | Africa (Egypt) | [44] | ||

| Barbus grypus (Shabout), Barbus sharpeyi (Bunnei), Carasobarbus luteus (Yellow barbell)—Cypriniformes; Planiliza abu (Abu mullet)—Mugiliformes | Asia (Iraq) | [33] | ||

| Neoarius graeffei (Blue salmon catfish)—Siluriformes | Australia (Brisbane River) | [45] | ||

| Leocottus kesslerii (Kessler’s sculpin)—Perciformes | Asia (Lake Baikal) | [46] | ||

| Cyrilia lignieresi Laveran, 1906 | Synbranchus marmoratus (Marbled swamp eel)—Synbranchiformes | South America (Belem, Para, North Brazil) | Macrogamonts: 5.0–11 Microgamonts: 4.7–88 | [7,47] |

| Cyrilia sp. | Potamotrygon cf. Histrix (Porcupine river stingray)—Myliobatiformes | South America (Mariua Archipelago, Negro River, in the Brazilian Amazon Basin) | Trophozoite or merozoite: 2.5 ± 0.6 × 12.6 ± 1.5 Nucleus: 2.2 ± 0.6 × 4.4 ± 1.0 Meronts: 5.1 ± 1.1 × 12.1 ± 1.7 Nucleus: 4.7 ± 1.1 × 4.4 ± 0.9 Pregamonts: 4.7 ± 0.6 × 18.5 ± 1.5 Nucleus: 4.1 ± 0.6 × 4.3 ± 0.9 Macrogamonts: 5.8 ± 0.7 × 15.8 ± 1.6 Nucleus: 5.3 ± 0.8 × 4.3 ± 0.8 Microgamonts: 4.6 ± 1.0 × 13.3 ± 1.6 Nucleus: 4.3 ± 0.9 × 4.4 ± 0.8 | [47] |

| Hepatozoon caimani Carini, 1909 | Hoplias aimara (anjumara) —Characiformes | South America (Eastern Amazon) | Cysts: 9.8 × 10.28 Cystozoites: 1.68 × 11.04 | [48] |

Table A3.

Calyptospora species currently recognized in freshwater hosts and morphometric parameters of this species.

Table A3.

Calyptospora species currently recognized in freshwater hosts and morphometric parameters of this species.

| Fish Order | Species | Type Host | Type Locality | Site of Infection | Oocysts | Sporocysts | Sporozoites | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Size (µ) | Sporocyst Residuum | Size (µ) | Size (µ) | ||||||

| Cichliformes | Calyptospora paranaidji Silva et al., 2019 | Cichla piquiti (Blue Peacock Bass) | South America (Tocantins River, Brazil) | liver | spherical | 22.1 ± 1.5 × 22.1 ± 1.5 | + | 4.6 ± 0.6 × 9.7 ± 0.5 | [69] | |

| Calyptospora spinosa Azevedo et al., 1994 | Crenicichla lepidota (Pike cichlid) | South America (Amazon river, Brazil) | liver, gonads | spherical | 21.5–23.4 × 21.5–23.4 | - | 3.6–4.1 × 8.9–9.5 | [68] | ||

| Calyptospora tucunarensis Bekesi & Molnar, 1991 | Cichla ocellaris (Peacock cichlid) | South America (River Curfi, Brazil) | liver | spherical | 23.0–26.0 × 23.0–26.0 | - | 3.5–5.0 × 7.2–9.1 | 1.1–1.4 × 5.4–6.3 | [67] | |

| Calyptospora sp. | Cichla temensis (Speckled pavon, | South America (Brazil) | liver | spherical | 21.2 × 21.2 | - | 3.1 × 9.2 | [75] | ||

| Aequidens plagiozonatus | South America (Brazil) | liver | [76] | |||||||

| Characiformes | Calyptospora gonzaguensis Silva et al., 2020 | Triportheus angulatus (Dusky Narrow Hatchetfish) | South America (Eastern Brazilian Amazon) | liver, gallbladder, adipose tissue | spherical | 19.6 ± 1.4 × 19.6 ± 1.4 | + | 3.9 ± 0.2 × 9.2 ± 0.6 | [70] | |

| Calyptospora serrasalmi Cheung et al., 1986 | Serrasalmus niger (Redeye piranha) | South America (Amazon, Brazil) | liver | spherical | 23.8 ± 1.5 × 23.8 ± 1.5 | + | 5.9 ± 0.4 × 11.7 ± 1 | [65] | ||

| Serrasalmus striolatus, S. rhombeus (Redeye piranha) | South America (Amazon, Brazil) | liver | spherical | 25.5 × 25.5 | + | 6.0 × 11.8 | [66] | |||

| Calyptospora sp. | Triportheus guentheri, Tetragonopterus chalceus | South America (Brazil) | liver, intestine | spherical | 24.5 × 24.5 | - | 4.5 × 11.5 | [73] | ||

| Calyptospora empristica Fournie et al., 1985 | Fundulus notti (Sterlet sturgeon)—Cyprinodontiformes | North America (Mississippi) | liver | spherical | 19.6–24.5 × 19.6–24.5 | - | 7.0–9.5 × 4.5–7.5 | [71] | ||

| Calyptospora sp. | Brachyplatystoma vaillantii (Laulao catfish)—Siluriformes | South America (Brazil) | liver | spherical | 20.8 × 20.8 | - | 4.1 × 8.9 | [74] | ||

| Calyptospora sp. | Arapaima gigas (Arapaima)—Osteoglossiformes | South America (Amazon, Brazil) | liver | spherical | 19.0 ± 4.2 × 19.0 ± 4.2 | - | 4.0 ± 0.4 × 9.0 ± 1.4 | [72] | ||

Table A4.

Cryptosporidium species and genotypes currently recognized in freshwater hosts and morphometric parameters of this species.

Table A4.

Cryptosporidium species and genotypes currently recognized in freshwater hosts and morphometric parameters of this species.

| Species | Type Host | Other Natural Hosts | Identification Technique | Geographic Origin | Site of Infection | Oocyst Size (mean ± S. D.; μ): | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium molnari Álvarez-Pellitero & Sitjà-Bobadilla, 2002 | Sparus aurata (Giilthead sea bream)—(marine fish) | Dicentrarchus labrax (European sea bass)—(marine fish) | PCR, histological analysis | Cantabric, Mediterranean, South Atlantic, Spain | stomach | 4.7 ± 0.5 × 4.5 ± 0.5 | [88] |

| Synodontis nigriventris (Upside down cat fish)—Siluriformes | PCR | Western Australia | stomach | [98] | |||

| Maccullochella peelii peelii (Murray cod) –Centrarchiformes | Fluorescent-antibody staining assay | Australia | stomach | 4.0 × 5.0 | [99] | ||

| Esox lucius (Northern pike)—Esociformes | PCR, histological analysis | Europe (Lake Geneva, France) | stomach | [100] | |||

| Onchorhynchus mykiss (Rainbow trout)—Salmoniformes | PCR, microscopy | Europe (Galicia, NW Spain) | pyloric caeca, intestine | [101] | |||

| Clarias gariepinus (North African catfish) –Siluriformes | PCR, microscopy, ELISA | Africa (Egypt) | stomach | 3.20–4.5 × 3.90–6.05 | [102] | ||

| Clarias gariepinus (North African catfish)—Siluriformes | Microscopy, ELISA, PCR | Africa (Nile river) | stomach | [103] | |||

| Cryptosporidium molnari—like | Crossocheilus aymonieri (Golden algae eater)—Cypriniformes; Synodontis nigriventris (Blotched upsidedown catfish)—Siluriformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [98] | ||

| Poecilia reticulata (Guppy)—Cyprinodontiformes | PCR, microscopy, histological analysis | Australia | stomach | [104] | |||

| Carassius auratus (Goldfish)—Cypriniformes; Poecilia reticulate (Guppy)—Cyprinodontiformes; Astronotus ocellatus (Oscar)—Cichliformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [93] | |||

| Salmo trutta (Sea trout)—Salmoniformes | Immunofluorescence microscopy | Europe (Galicia, NW Spain) | intestine | [105] | |||

| Cryptosporidium huwi Ryan et al., 2015 | Poecilia reticulate (Guppy)—Cyprinodontiformes | Paracheirodon innesi (Neon tetra), Puntigrus tetrazona (Tiger barb), Moenkhausia sanctaefilomenae (Red eye tetra)—Characiformes | PCR | Australia | intestine, stomach | [89,93,98,106] | |

| Cryptosporidium bollandi Bolland et al., 2020 | Pterophyllum scalare (Freshwater angelfish)—Cichliformes | PCR | South America (USA, Washington) | intestine, stomach | 3.11 ± 0.45 × 2.82 ± 0.42 | [107] | |

| Astronotus ocellatus (Oscar)—Cichliformes; Paracheirodon innesi (Neon tetra)—Characiformes | PCR | Australia | intestine, stomach | [89,93,98,108] | |||

| Cryptosporidium abrahamseni Zahedi et al., 2021 | Moenkhausia sanctaefilomenae (Redeye tetra)—Characiformes | Paracheirodon innesi (Neon tetra)—Characiformes | PCR, histological analysis | Western Australia, Perth | intestine | 3.82 ± 0.22 × 3.16 ± 0.18 | [93,95,106,107] |

| Cryptosporidium parvum Tyzzer, 1912 | Mus musculus (House mouse) | Onchorhynchus mykiss (Rainbow trout)—Salmoniformes | IFAT | Europe (Spain rivers) | gastrointestinal tract | 5.0 × 7.0 | [109] |

| Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia)—Cichliformes; Puntius gonionotus (Silver barb)—Cypriniformes | PCR | Australia (New Guinea) | intestine, stomach | [110] | |||

| Rutilus rutilus (Roach)—Cypriniformes; Perca fluviatilis (European perch)—Perciformes; Salvelinus alpinus (Arctic char), Coregonus lavaretus (European whitefish)—Salmoniformes; Esox lucius (Northern pike)—Esociformes | PCR, histological analysis | Europe (Lake Geneva, France) | intestine, stomach | [100] | |||

| Onchorhynchus mykiss (Rainbow trout)—Salmoniformes | PCR, microscopy | Europe (Galicia, NW Spain) | pyloric caeca, intestine | [101] | |||

| Salmo trutta (Sea trout)—Salmoniformes | Microscopy | Europe (Galicia, NW Spain) | intestine | [105] | |||

| Carassius auratus (Goldfish)—Cypriniformes | PCR, microscopy | Asia (Iran) | intestine | [111] | |||

| Cryptosporidium hominis Morgan-Ryan et al., 2002 | Homo sapiens (Human) | Salmo salar (Atlantic salmon), Salmo trutta (Sea trout)—Salmoniformes | PCR | Europe (England) | intestine | [112] | |

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Cyprinus carpio (Common carp)—Cypriniformes | Microscopy | Europe (Czechoslovakia) | intestine | [92] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Oreochromis aureus (Blue tilapia) × Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia)—Cichliformes | Microscopy, histological analysis | Meronts: 2.4–3.1 × 3.1–3.7 Macrogamonts: 2.2–4.8 × 3.4–7.0 Microgamonts: 2.8–3.1 × 3.8–4.4 Oocysts: 2.5– 4.0 × 3.5–4.7 | [113] | |||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Oreochromis aurea (Blue tilapia)—Cichliformes | Microscopy | Europe (lake Kinneret, Israel) | stomach | [114] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Salmo trutta (Sea trout)—Salmoniformes | Microscopy | Europe (England) | intestine | [115] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Tilapia nilotica = Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia)—Cichliformes; Clarias lazera= Clarias gariepinus (North African catfish), Bagrus bajad (Bayad)—Siluriformes | Microscopy | Africa (Egypt) | feces | 3.0 × 5.0 | [116] | |

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Plecostomus sp. (Catfish)—Siluriformes | Microscopy, histological analysis | South America | intestine | [117] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Planiliza abu (Abu mullet)—Mugiliformes | Microscopy | Asia (Tigers River, Mosul, Iraq) | 3.0 × 7.0 | [118] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Pterophyllum scalare (Freshwater angelfish) –Cichliformes | PCR | North America | gastric epithelial cells | 3.4 ± 0.4 × 3.4 ± 0.4 | [108] | |

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Clarias gariepinus (North African catfish)—Siluriformes | Microscopy | Africa (lakes and ponds in Zaria, Nigeria) | gastrointestinal tract and gills | [119] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Pterophyllum scalare (Angelfish)—Cichliformes; Poecilia latipinna (Sailfin molly)—Cyprinodontiformes | Microscopy | Asia (Iran) | intestine | [120] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Onchorhynchus mykiss (Rainbow trout)—Salmoniformes | PCR, microscopy | Europe (Galicia, NW Spain) | pyloric caeca, intestine | [101] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Poecilia latipinna (Sailfin molly), Xiphophorus maculatus (Platy)—Cyprinodontiformes; Pethia conchonius (Rosy barb), Carassius auratus (goldfish)—Cypriniformes; Trichopodus leerii (pearl gourami), Betta splendens (Siamese fighting fish)—Anabantiformes; Labidochromis caeruleus (Electric yellow)—Cichliformes. | PCR, microscopy | Asia (Iran) | intestine | [111] | ||

| Cryptosporidium sp. | Abramis brama (Freshwater bream), Rutilus caspicus (Caspian roaches), Carassius gibelio (Prussian carp)—Cypriniformes | Microscopy | Asia (Kura River) | gut epithelium | 3.12–4.52 × 3.34–5.01 | [121] | |

| Pisgine genotype III | Carassius auratus (Goldfish)—Cypriniformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [93] | ||

| Pisgine genotype IV | Astronotus ocellatus (Oscar)—Cichliformes; Crossocheilus aymonieri (Golden algae eater)—Cypriniformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [98] | ||

| Paracheirodon innesi (Neon tetra)—Characiformes | PCR | Australia | intestine, stomach | [106] | |||

| Apteronotus albifrons (Black ghost)—Gymnotiformes | PCR | Australia | intestine, stomach | [107] | |||

| Pisgine genotype V | Pterophyllum scalare (Angelfish)—Cichliformes; Crossocheilus aymonieri (Golden algae eater)—Cypriniformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [98] | ||

| Pterophyllum altum (Angelfish)—Cichliformes; Apteronotus albifrons (Black ghost)—Gymnotiformes; Carassius auratus (Goldfish)—Cypriniformes; Poecilia reticulate (Guppy), Xiphophorus maculatus (Southern platyfish)—Cyprinodontiformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [93] | |||

| Pisgine genotype VI | Poecilia reticulate (Guppy)—Cyprinodontiformes, | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [98] | ||

| Trichogaster trichopterus (Three spot gourami)—Anabantiformes | PCR | Australia | intestine, stomach | [106] | |||

| Novel genotype | Astronotus ocellatus (Oscar)—Cichliformes; Cyprinus carpio (Common carp)—Cypriniformes | PCR | Western Australia | intestine, stomach | [91,93] | ||

| Rat genotype III | Carassius auratus (Goldfish)—Cypriniformes | PCR | Australia | intestine, stomach | [106] |

Table A5.

Eimeria species recognized in freshwater hosts and their morphometric parameters.

Table A5.

Eimeria species recognized in freshwater hosts and their morphometric parameters.

| Fish Order | Species | Type Host | Type Locality | Site of Infection | Oocysts | Sporocysts | Sporozoites | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Mycropile | Polar Granule | Oocyts Residuum | Size (µ) | Sporocyst Residuum | Stieda Body | Size (µ) | Size (µ) | ||||||

| Cypriniformes | Eimeria amudarinica Davronov, 1987 | Scardinius erythrophthalmus (Rudd) | Eurasia | intestine | spherical | - | + | - | 22.1–28.9 × 22.1–28.9 | - | + | 5.1–8.6 × 15.3–18.7 | [9] | |

| Eimeria amurensis Dogiel & Akhperov, 1959 | Pseudorasbora parva (Stone moroko), Sarcocheilichthys sinensis (Chinese lake gudgeon) | Asia | liver, kidneys | spherical | - | - | - | 18.0–29.2 × 18.0–29.2 | - | - | 7.3–8.6 × 12–15 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria aristichthysi Lee & Chen, 1964 | Aristichthys nobilis (Bighead carp), Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Silver carp) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 10.5–13.3 × 10.5–13.3 | + | - | 7.8–9.4 × 3.9–4.4 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria aurati Hoffman, 1965 (Syn.: Goussia aurati Hoffman, 1965) | Carassius auratus (Goldfish) | North America (Pennsylvania, U.S.A) | anterior intestinal epithelium, feces | ellipsoid | - | - | - | 14.0–17.0 × 16.0–24.0 | - | - | 6.5–8.0 × 11.0–13.0 | 2.0–2.5 × 10.0–13.0 | [125] | |

| Eimeria barbi Davronov, 1987 | Luciobarbus capito (Bulatmai barbel) | Eurasia (Aral, Caspian basin) | intestine | ellipsoid | + | - | - | 17.0–23.8 × 20.4–27.2 | + | + | 5.1–8.5 × 6.8–11.9 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria baueri Alvarez-Pellitero & Gonzalez-Lanza, 1986 | Carassius carassius (Crucian carp) | Eurasia (Esla River) | kidneys, spleen, liver, urinary tract, gallbladder, heart | subspherical | - | - | - | 13.5–19.0 × 15.5–22.5 | + | + | 5.5–7.5 × 9.5–13.0 | 2.0–3.0 × 8.0–13.5 | [126] | |

| Eimeria branchiphila Dyková, Lom & Grupcheva, 1983 | Rutilus rutilus (Roach) | Eurasia | kidneys, spleen, muscles and brain | ellipsoidal | - | - | - | 9.0–10.0 × 19.0–22.0 | + | + | 4.0–5.0 × 8.0–10.0 | [127] | ||

| Eimeria carassii Yakimoff & Gousseff, 1935 | Carassius carassius (Crucian carp) | Eurasia (Belorusia) | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 19.52–4.4 × 19.52–24.4 | - | - | [9] | |||

| Eimeria carassiusaurati Rodriguez, 1978 | Carassius carassius (Crucian carp) | Eurasia | intestine | spherical | - | + | - | 13.3–15.2 × 13.3–15.2 | + | - | 5.8 × 13.6 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria catostomi Molnár & Hanek, 1974 | Catostomus commersoni (White sucker) | North America (Ontario) | mucus and epithelium of the foregut | spherical | - | + | - | 6.5–7.5 × 6.5–7.5 | + | - | 3.6–4.0 × 5.2–5.9 | 4.4–4.8 × 1.3–1.6 | [128] | |

| Eimeria cheissini Schulman & Zaika, 1962 | Gobio gobio (Gudgeon), Hemibarbus labeo (Barbel steed), Hemiculter leucisculus (Sharpbelly), Leuciscus leuciscus (Common dace) | Eurasia | pleura, wall of intestine, gallbladder | spherical | - | - | - | 18.0–22.0 × 18.0–22.0 | + | - | 6.0–8.0 × 8.5–10.5 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria chenchingensis Chen, 1984 | Carassius carassius (Crucian carp) | Eurasia | spleen | oval | - | - | - | 7.3–19.2 × 21.5–23.8 | + | - | [9] | |||

| Eimeria cobitis Stankovitch, 1923 | Cobitis taenia (Spined loach), C. lutheri (Luther’s spiny loach) | Eurasia | liver | spherical | - | - | - | 19.0–21.0 × 19.0–21.0 | + | - | 7.0 × 14.0–15.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria ctenopharyngodoni Li, Wen et Yu, 1995 | Ctenopharyngodon idella (Grass carp) | Asia | kidneys | spherical | - | - | - | 21.4–30.4 × 21.4–30.4 | + | - | 15.3 × 19.5 | 3.1–4.6 × 12.2–16.5 | [9] | |

| Eimeria culteri Lee & Chen, 1964 | Erythroculter erythropterus (Predatory carp) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 10.1 × 10.1 | + | - | 6.7 × 7.2 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria cylindrospora Stankovich, 1921 | Alburnus alburnus (Bleak) | Europe | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 10.0–11.0 × 10.0–11.0 | + | - | 3.5–4.5 × 7.0–8.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria cyprinorum Stankovich, 1921 (syns. Goussia carpelli Léger & Stankovitch, 1921, Eimeria carpelli Léger et Stankovitch, 1921; Eimeria cyprini Plehn, 1924) | Abramis brama (Freshwater bream), Alburnus alburnus (Bleak), Barbus barbus (Barbel), Leucaspius delineates (Belica), Phoxinus phoxinus (Eurasian minnow), Rhodeus sericeus (Bitterling), Rutilus rutilus (Roach), Scardinius erythrophthalmus (Rudd) | Eurasia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 8.5–13.0 × 8.5–13.0 | + | - | 3.5–4.5 × 6.0–8.0 | [9] | ||

| Abramis brama (Freshwater bream), Rutilus caspicus (Caspian roaches), Alburnus filippi (Kura bleak) | Asia (Kura River) | gut epithelium | spherical | - | - | - | 12.0–14.0 × 12.0–14.0 | + | - | 4.5 × 7.5 | [121] | |||

| Eimeria degiustii Molnár & Fernando, 1974 | Notropis cornutus (Common shiner), Pimephales notatus (Bluntnose minnow), P. promelas (Fathead minnow) | North America (Ontario) | speleen | spherical | - | + | - | 19.2–22.0 × 19.2–22.0 | + | - | 6.5–8.5 × 13.0–14.5 | 2.5–2.8 × 10.5–12.0 | [129] | |

| Eimeria fernandoae Molnár & Hanek, 1974 | Catostomus commersoni (White sucker) | North America (Ontario) | mucus and epithelium of the foregut | ellipsoid | - | - | - | 6.5–7.0 × 7.8–9.0 | + | - | 2.6–3.4 × 6.8–7.5 | 1.0–1.3 × 5.2–6.5 | [128] | |

| Eimeria freemani Molnár & Fernando, 1974 | Notropis cornutus (Common shiner) | North America (Ontario) | kidneys, renal parenchyma, renal tubes | ellipsoid | - | + | - | 17.0–18.0 × 22.0–24.0 | + | - | 5.0–6.5 × 16.0–17.0 | 2.5–3.5 × 14.0–15.5 | [129] | |

| Eimeria haichengensis Chen, 1984 | Cyprinus carpio (Common carp) | Eurasia (Basin Amur) | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 7.7–8.6 × 7.7–8.6 | + | - | 3.4 × 4.7 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria hemibarba Su & Chen, 1987 | Hemibarbus maculatus (Spotted steed) | Eurasia (Basin Amur) | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 9.0–10.0 × 9.0–10.0 | + | - | 4.0–4.5 × 5.5–7.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria hemiculterii Chen & Hsieh, 1964 | Hemiculter leucisculus (Sharpbelly) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 9.9–11.6 × 9.9–11.6 | + | - | 3.9 × 4.4 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria huanggangensis Su & Chen, 1987 | Misgurnus mohoity (Misgurnus) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 31.0–39.0 × 31.0–39.0 | + | - | 8.5 × 19.8 | 4.7 × 12.7 | [9] | |

| Eimeria hupehensis Chen & Hsieh, 1964 | Carassius auratus (Goldfish) | Asia | intestine | spherical or irregular | 9.2–11.1 × 9.2–11.1 | 4.4–5.6 × 6.6–7.8 | [9] | |||||||

| Eimeria hybognath Molnar & Fernando, 1974 | Hybognathus hankinsoni (Brassy minnow) | North America (Ontario) | gut epithelium, feces | spherical | - | - | - | 14.0–14.5 × 14.0–14.5 | + | - | 5.7–6.0 × 9.5–10.0 | 2.0–2.6 × 9.0–9.2 | [129] | |

| Eimeria hypophthalmichthys Dogiel & Akhperov, 1959 | Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Silver carp) | Asia | kidneys | spherical | - | - | + | 21.0–24.0 × 21.0–24.0 | + | - | 2.5 × 16.0–18.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria iroquoina Molnar & Fernando, 1974 | Notropis cornutus (Common shiner) | North America (Ontario) | gut epithelium, feces | spherical | - | - | - | 9.0–11.0 × 9.0–11.0 | + | - | 4.0–4.5 × 7.8–8.0 | 1.5–1.7 × 7.5–7.7 | [129] | |

| Eimeria liaohoensis Chen, 1984 | Carassius auratus (Goldfish) | Asia | kidneys | spherical | - | - | + | 24.2–30.8 × 24.2–30.8 | + | - | [9] | |||

| Eimeria liaoningensis Chen, 1984 | Carassius auratus (Goldfish), Abbotina rivularis (Chinese false gudgeon) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 7.3–8.4 × 7.3–8.4 | + | - | [9] | |||

| Eimeria liuhaoensis Li, Wen &Yu, 1995 | Aristichthys nobilis (Bighead carp), Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Silver carp) | Asia | intestine | spherical or ellipsoid | - | - | - | 20.3–25.9 × 21.3–29.3 | + | - | 6.1–8.7 × 13.3–18.8 | 2.3–4.6 × 11.2–16.3 | [9] | |

| Eimeria macroresidualis Schulman & Zaika, 1964 | Romanogobio albipinnatus (White-finned gudgeon) | Eurasia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 8.5–18.0 × 8.5–18.0 | + | - | 5–6.5 × 10.5–12 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria misgurni Stankovitch, 1923 | Cobitis taenia (Spined loach), Misgurnus fossilis (Weatherfish), M. mohoity (Misgurnus) | Eurasia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 15.0–16.0 × 15.0–16.0 | + | - | 5.3 × 11.0–12.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria molnari Jastrzębski, 1982 | Gobio gobio (Gudgeon) | Europe | middle part of the digestive tract | oval | - | - | - | 11.4–13.8 × 18.6–20.5 | + | - | 4.9–6.1 × 10.2–12.5 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria muraiae Molnár, 1978 | Misgunus fossilis (Weatherfish) | Europe (Hungary) | kidneys, renal tubes | ellipsoid or oval | - | - | - | 35.8– 37.1 × 45.5–47.0 | + | - | 8.4–9.5 × 22.1–24.8 | 5.1–5.5 × 17.2–18.1 | [130] | |

| Eimeria nemethi Molnár, 1978 | Alburnus alburnus (Bleak) | Europe (Hungary) | kidneys, liver, spleen | ellipsoid | - | - | - | 11.5–13.5 × 17.0–20.2 | + | + | 3.9–4.1 × 11.4–12.6 | 2.1–2.5 × 6.9–7.5 | [130] | |

| Eimeria newchongensis Chen, 1984 | Carassius auratus (Goldfish), Erythroculter erythropterus (Predatory carp) | Asia | intestine, liver | spherical | - | - | + | 17.3–20.0 × 17.3–20.0 | [9] | |||||

| Eimeria nicollei Yakimoff & Gousseff, 1935 | Carassius auratus (Goldfish), | Asia | intestine | oval | - | - | - | 13.0–19.0 × 22.0–32.0 | + | - | [9] | |||

| Eimeria ochetobiusi Lee & Chen, 1964 | Ochetobius elongates (Ochetobius) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 7.8 × 7.8 | + | - | 2.8–3.3 × 5.6–6.4 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria orientalis Chen, 1984 | Misgurnus mohoity (Misgurnus) | Asia | kidneys | spherical | - | - | + | 26.2–34.8 × 26.2–34.8 | [9] | |||||

| Eimeria pastuszkoi Jastrzębski, 1982 | Barbatula barbatulus (Stone loach) | Europe | intestine | subspherical | - | - | - | 11.4–12.1 × 13.1–14.6 | + | - | 4.0– 6.2 × 8.9–11.2 | 1.8–2.9 | [9] | |

| Eimeria pseudorasbori Chen, 1984 | Pseudorasbora parva (Stone moroko) | Asia | kidneys | spherical | - | - | - | 24.2–28.8 × 24.2–28.8 | + | - | [9] | |||

| Eimeria radae Moshu, 1992 | Cobitis taenia—(Spined loach) | Eurasia | kidneys, rarely in the liver and intestinal contents | oval | - | + | - | 19.2–28.8 × 24.0–30.0 | + | - | 8.4–11.2 × 15.6–21.2 | 2.8–4.2 × 7.2–12.5 | [9] | |

| Eimeria rhodei Kandilov, 1964 | Rhodeus sericeus (Bitterling) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 19.0 × 19.0 | - | - | 6.3 × 10.5 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria rouxi Elmassian, 1909 | Tinca tinca—(Tench) | Eurasia | small intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 10.0 × 10.0 | - | - | 6.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria rutili Dogiel & Bychowsky, 1939 | Rutilus rutilus (Roach) | Eurasia | kidneys, intestine | oval, elliptical | - | - | - | 8.0–11.0 × 27.0– 32.0 | + | - | 5.0 × 10.5–12.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria saurogobii Chen, 1984 | Saurogobio dabryi (Chinese lizard gudgeon), Ctenopharyngodon idella (Grass carp) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 8.5–9.2 × 8.5–9.2 | + | - | 4.4–5.6 × 5.6–7.8 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria schulmani Kulemina, 1969 | Leuciscus cephalus (Chub), L. idus (Ide) | Eurasia | feces | spherical | - | - | - | 18.0–22.0 × 18.0–22.0 | + | - | 6.9–7.8 × 15.0–17.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria strelkovi Schulman & Zaika, 1962 | Pseudorasbora parva (Stone moroko) | Asia | kidneys | spherical | - | - | - | 15.0–16.0 × 15.0–16.0 | + | - | 6.6–7.6 × 9.0–10.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria syrdarinica Davronov, 1987 | Ctenopharyngodon idella (Grass carp) | Asia | feces | spherical | - | - | + | 20.4–30.6 × 24.0–30.6 | - | - | 8.5–11.9 × 13.6–18.7 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria sp. | Carassius auratus (Goldfish) Puntius conchonius (Rosy barb) | Asia (Iran) | [120] | |||||||||||

| Percciformes | Eimeria acerinae Pellérdy & Molnár, 1971 | Gymnocephalus cernuus (Ruffe) | Eurasia | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 10.0–12.0 × 10.0–12.0 | + | - | 5.0–5.5 × 8.0–8.5 | 2.0–2.5 × 8.5–9.0 | [9] |

| Eimeria cotti Gauthier, 1921 | Cottus gobio (Bullhead) C.cognatus (Slimy sculpin) | Europe North America | intestine | spherical | - | - | - | 9.0–11.0 × 9.0–11.0 | + | + | 4.2 × 7.5 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria daviesae Molnár, 2000 | Ponticola kessleri (Bighead goby) | Europe (River Danube, Budapest) | mucus and epithelium of the foregut | spherical | - | + | - | 13.0–14.0 × 13.0–14.0 | - | + | 4.8–5.2 × 7.5–8.2 | 1.8–2.3 × 9.5–10.0 | [131] | |

| Eimeria duszynskii Conder, Oberndorfer, & Heckmann, 1980 | Cottus bairdi (Mottled sculpin) | North America (Utah, U.S.A.) | intestinal epithelium, feces | irregular | - | - | - | 11.6 × 12.9 | - | - | 6.5–8.0 × 11.0–13.0 | 2.0–2.5 × 10.0–13.0 | [132] | |

| Eimeria etheostomae Molnár & Hanek, 1974 | Etheostoma exile (Iowa darter) | North America (Ontario) | mucus and epithelium of the foregut | spherical | - | - | - | 9.1–10.4 × 9.1–10.4 | + | - | 5.2–6.3 × 8.4–10.0 | 1.4–1.8 × 7.8–9.0 | [128] | |

| Eimeria fluviatili Belova & Krylov, 2001 | Perca fluviatilis (European perch) | Eurasia (Neman river) | feces | spherical | - | - | + | 20.0–22.5 × 20.0–22.5 | - | + | 7.5 × 12.5 | [133] | ||

| Eimeria haneki Molnar & Fernando, 1974 | Culaea inconstans (Brook stickleback) | North America (Ontario) | gut epithelium, feces | spherical | - | + | - | 7.1–7.8 × 7.1–7.8 | + | - | 3.9–4.5 × 5.6–6.5 | 1.3–2.0 × 5.6–6.0 | [129] | |

| Eimeria kwangtungensis Chen & Hsieh, 1960 | Ophiocephalus argus (Snakehead) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | + | - | 9.1–11.9 × 9.1–11.9 | + | - | 3.5–5.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria laureleus Molnár & Fernando, 1974 | Perca flavescens (American yellow perch) | Norta America | gut epithelium, feces | spherical | - | - | - | 11.0–12.0 × 11.0–12.0 | + | - | 5.0–5.8 × 9.2–11.0 | 1.5–2.0 × 9.0–10.0 | [129] | |

| Eimeria macropoda Su & Chen, 1991 | Macropodus opercularis (Paradisefish) | Asia (Japan, China, Korea) | gut epithelium, feces | spherical | - | - | - | 9.0–10.2 × 9.0–10.2 | + | - | 6.7–7.7 × 3.1–3.8 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria micropteri Molnár & Hanek, 1974 | Micropterus salmoides (Largemouth black bass) | North America (Ontario) | mucus and epithelium of the foregut | spherical | - | - | - | 11.7–12.5 × 11.7–12.5 | + | - | 6.0–6.5 × 11.0–11.7 | 2.0–2.2× 8.9–9.3 | [128] | |

| Eimeria odontobutis Su & Chen, 1987 | Odontobutis obscura (Odontobutis) | Asia | intestine | spherical | - | + | - | 11.9–14.8 × 11.9–14.8 | + | + | 4.7–5.0 × 7.2–8.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria ojibwana Molnár & Fernando, 1974 | Cottus bairdi (Mottled sculpin) | North America (Ontario) | gut epithelium, feces | spherical | - | - | - | 10.4–11.0 × 10.4– 11.0 | + | - | 5.0–5.8 × 9.0–9.2 | 2.0–2.5 × 8.4–8.7 | [129] | |

| Eimeria ophiocephalae Chen & Hsieh, 1960 | Ophiocephalus argus (Snakehead) | Asia | intestine | spherical | + | - | + | 7.3–10.0 × 7.3–10.0 | [9] | |||||

| Eimeria patersoni Lom, Desser & Dyková, 1989 | Lepomis gibbosus (Pumpkinseed) | North America | kidneys, liver, spleen | subspherical ellipsoid | - | - | - | 10.6 × 11.9 9.9 × 11.9 8.6 × 15.8 | + | - | 2.6–4.0 × 9.9–11.2 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria percae Riviere, 1914 | Perca fluviatilis (European perch) | Eurasia | liver and stomach wall | spherical | - | - | - | 12.0–13.0 × 12.0–13.0 | + | + | 5.0–6.0 × 8.0–9.0 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria piraudi Gauthier, 1921 | Cottus gobio (Bullhead) | Europe | intestinal wall | spherical | - | - | - | 11.0–12.0 × 11.0– 12.0 | + | - | 5.1 × 7.9 | [9] | ||

| Eimeria pungitii Molnár & Hanek, 1974 | ngitius pungitius (Ninespine stickleback) | North America (Ontario) | foregut epithelium, feces | ellipsoid | - | - | - | 8.6–10.4 × 12.1–13.0 | + | - | 3.4–3.9 × 9.1–10.4 | 2.1–2.4 × 8.4–9.1 | [128] | |

| Eimeria stizostedioni Belova & Krylov, 2003 | Sander lucioperca (Pike-perch) | Eurasia (Neva river) | feces | oval | - | - | - | 7.5–8 × 10–12.5 | + | + | 3.5 × 6.4 | 2.5 × 5.5 | [134] | |