Responses of Rhizosphere Fungal Communities to the Sewage Sludge Application into the Soil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Description and Sewage Sludge Used

2.2. Rhizosphere Sampling and DNA Isolation

2.3. Terminal-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism

2.4. Construction of 18S rDNA Clone Library

2.5. Statistical and Bioinformatic Analyses

2.6. GenBank Accession No.

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Genetic Diversity

3.2. T-RFLP and the Rhizosphere Fungal Communities

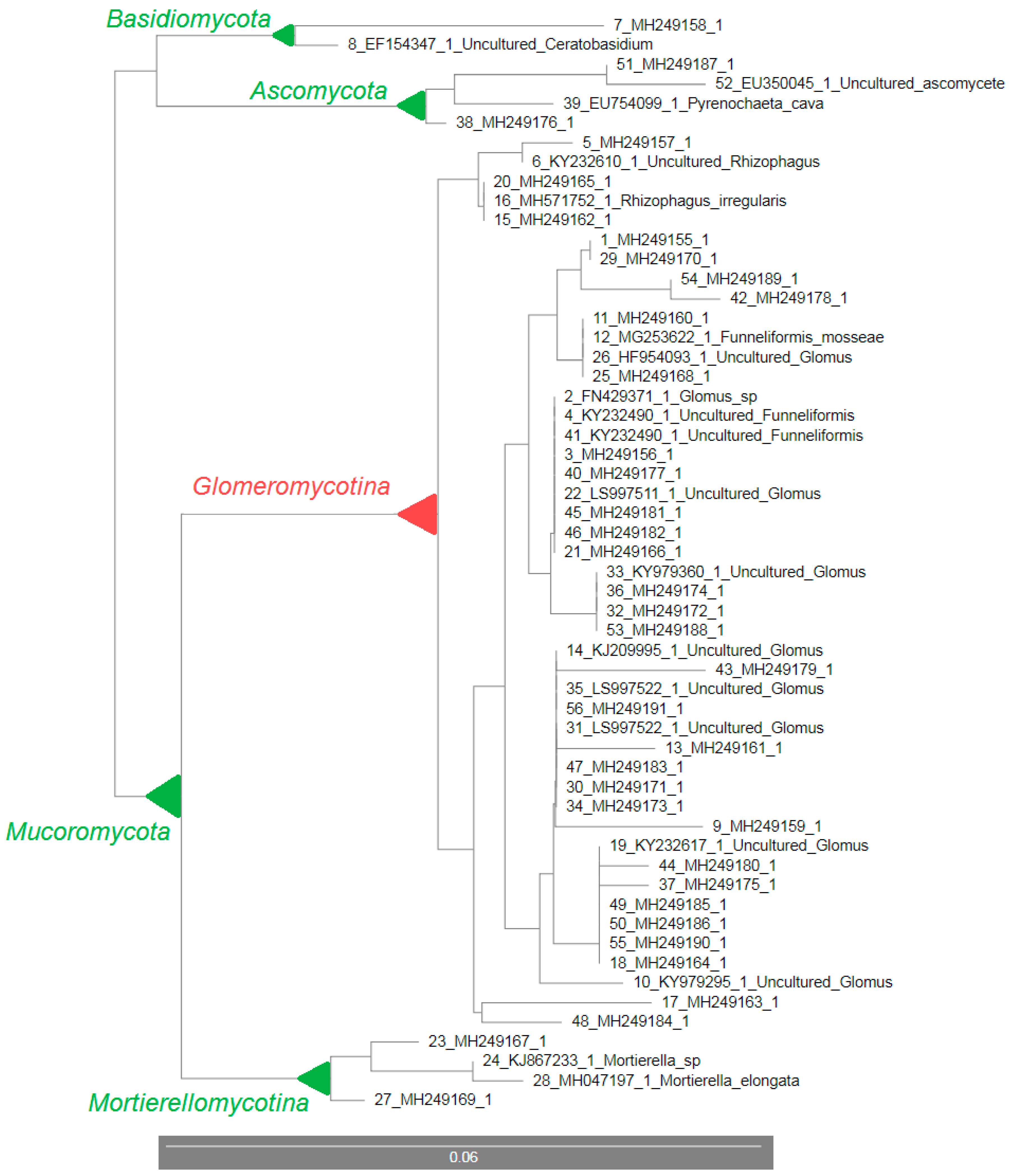

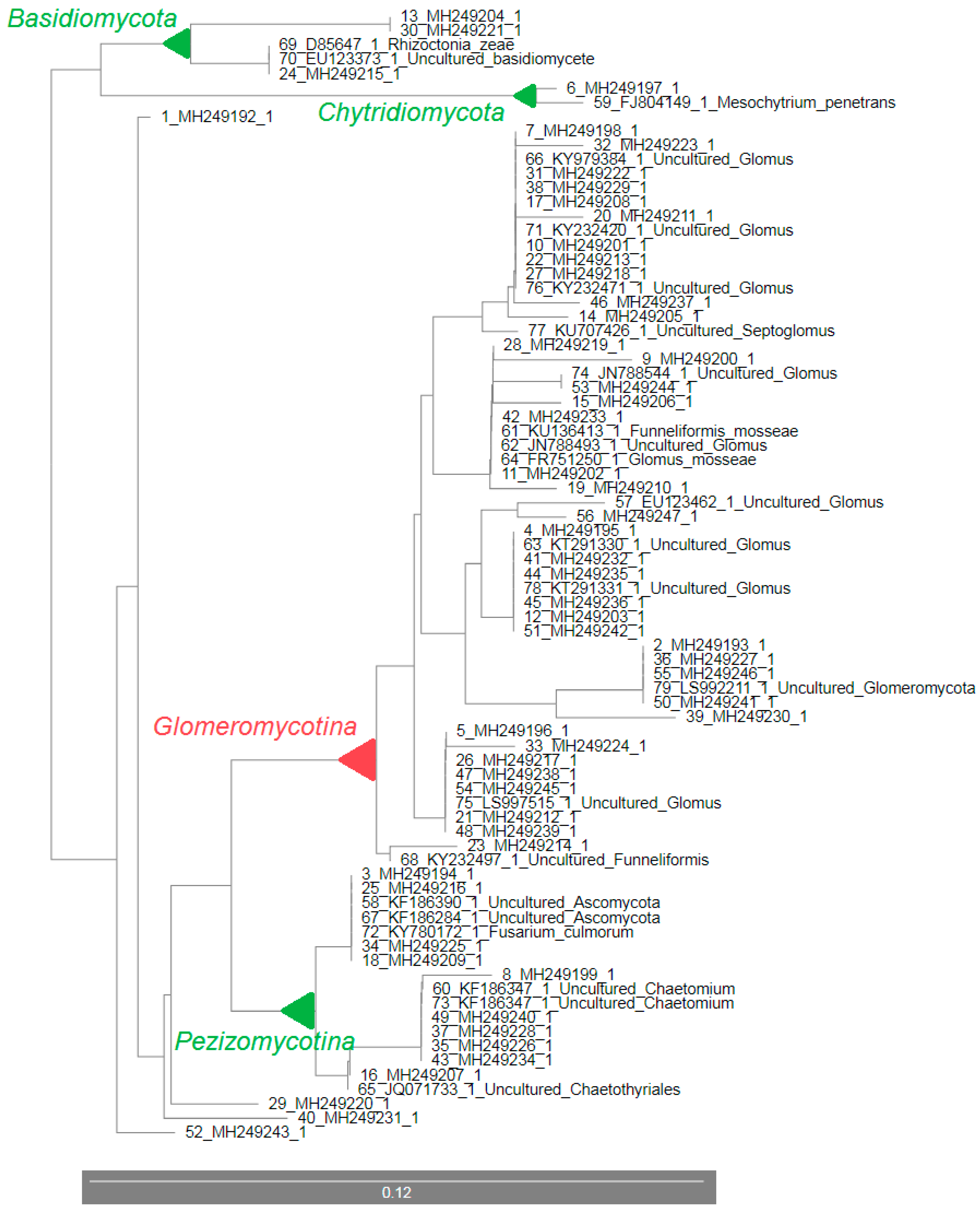

3.3. 18S rDNA Sequencing and the Rhizosphere Fungal Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat, the Statistical Office of the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Potential benefits and risks of land application of sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloret, E.; Pascual, J.A.; Brodie, E.L.; Bouskill, N.J.; Insam, H.; Juárez, M.F.D.; Goberna, M. Sewage sludge addition modifies soil microbial communities and plant performance depending on the sludge stabilization process. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 101, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielson, G.H.; Hogue, E.J.; Nielson, D.; Zebarth, B.J. Evaluation of organic wastes as soil amendments for cultivation of carrot and chard on irrigated sandy soils. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1998, 78, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda, G.; Alcaniz, J.M.; Ortiz, O. Runoff and losses by erosion in soils amended with sewage sludge. Land Degrad. Dev. 2003, 14, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, F.; Cuevas, G.; Calvo, R.; Walter, I. Biowaste effects on soil and native plants in a semiarid ecosystem. J. Environ. Qual. 2003, 32, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramulu, U.S.S. Reuse of Municipal Sewage and Sludge in Agriculture; Scientific Publishers: Jodhpur, India, 2001; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner, P.; Kandeler, E.; Marschner, B. Structure and function of the soil microbial community in a long-term fertilizer experiment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadet-Bourgeteau, S.; Houot, S.; Karimi, B.; Mathieu, O.; Mercier, V.; Montenach, D.; Morvan, T.; Sappin-Didier, V.; Watteau, F.; Nowak, V.; et al. Microbial communities from different soil types respond differently to organic waste input. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 143, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, I.; Vicente, M.A.; Lobo, M.C. Influence of the Application of Sewage Sludges on Soil Microbial Activity. Bioresour. Technol. 1996, 57, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbeva, P.; van Veen, J.A.; van Elsas, J.D. Microbial diversity in soil: Selection microbial populations by plant and soil type and implications for disease suppressiveness. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Widmer, F. Community structure analysis are more sensitive to differences in soil bacterial communities than anonymous diversity indices. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7804–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelot, B.; Uriarte, M.; Zimmerman, J.K.; Thompson, J.; Leff, J.W.; Asiaii, A.; Koshner, J.; McGuire, K. Long-lasting effects of land use history on soil fungal communities in second-growth tropical rain forests. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 1881–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wardle, D.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Klironomos, J.N.; Setälä, H.; van der Putten, W.H.; Wall, D.H. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 2004, 304, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanová, M.; Šnajdr, J.; Baldrian, P. Composition of fungal and bacterial communities in forest litter and soil is largely determined by dominant trees. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 84, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Geetanjali; Kaur, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal: Nutritional aspects. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2006, 52, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, Y.L. Phylogenetic distribution and evolution of mycorrhizas in land plants. Mycorrhiza 2006, 16, 299–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, N.; Chandel, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal networks: Process and functions. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klironomos, J. Host-Specificity and Functional Diversity among Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Microbial Ecology, Halifax, NS, Canada, 9–14 August 2000; Bell, C.R., Brylinski, M., Johnson-Green, P., Eds.; Atlantic Canada Society for Microbial Ecology: Halifax, NS, Canada; pp. 845–851. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowski, U. A journey through signaling in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.G. Mycorrhizoremediation—An enhanced form of phytoremediation. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2006, 7, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Adholeya, A. Prospects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soils. Curr. Sci. 2004, 86, 528–534. [Google Scholar]

- Vivas, A.; Barea, J.M.; Azcón, R. Interactive effect of Brevibacillus brevis and Glomus mosseae both isolated from Cd contaminated soil, on plant growth, physiological mycorrhizal fungal characteristics and soil enzymatic activities in Cd polluted soils. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 134, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilu, R.; Bucci, A.; Cerino Badone, F.; Landoni, M. Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.): A weed plant or a promising energy crop? Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 9163–9174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubišová, M.; Čičková, M.; Klčová, L.; Gubiš, J. In vitro tillering—An effective way to multiply high-biomass plant Arundo donax. Ind. Crop Prod. 2016, 81, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Young, J.P. Improved PCR primers for the detection and identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 2008, 65, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mummey, D.L.; Rillig, M.C.; Holben, W.E. Neighbouring plant influences on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community composition as assessed by T-RFLP analysis. Plant Soil 2005, 271, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.P.; Young, J.P.W.; Merryweather, J.W.; Fitter, A.H. Diversity of fungal symbionts in arbuscular mycorrhizas from a natural community. New Phytol. 1995, 130, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.P.; Fitter, A.H.; Young, J.P. Ribosomal small subunit sequence variation within spores of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, Scutellospora sp. Mol. Ecol. 1999, 8, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, T.; Faulkner, G.; Hugenholtz, P. Bellerophon: A program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 2317–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, L. Entropy and diversity. Oikos 2006, 113, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E.C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 1966, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D. Paleontological Data Analysis; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; p. 351. ISBN 1405115440. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, I.C.; Parkin, P.I.; Campbell, C.D. DNA- and RNA-derived assessments of fungal community composition in soil amended with sewage sludge rich in cadmium, copper and zinc. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerfahi, D.; Ogwu, M.C.; Ariunzaya, D.; Balt, A.; Davaasuren, D.; Enkhmandal, O.; Purevsuren, T.; Batbaatar, A.; Tibbett, M.; Undrakhbold, S.; et al. Metal-Tolerant Fungal Communities Are Delineated by High Zinc, Lead, and Copper Concentrations in Metalliferous Gobi Desert Soils. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, N.C.M.; Landi, L.; Smalla, K.; Nannipieri, P.; Brookes, P.C.; Renella, G. Effects of Cd- and Zn-enriched sewage sludge on soil bacterial and fungal communities. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavani, L.; Manici, L.M.; Caputo, F.; Peruzzi, E.; Ciavatta, C. Ecological restoration of a copper polluted vineyard: Long-term impact of farmland abandonment on soil bio-chemical properties and microbial communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastida, F.; Jehmlich, N.; Martínez-Navarro, J.; Bayona, V.; García, C.; Moreno, J.L. The effects of struvite and sewage sludge on plant yield and the microbial community of a semiarid Mediterranean soil. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossa, A.-W.; Dickinson, M.J.; West, H.M.; Young, S.D.; Crout, N.M.J. The response of soil microbial diversity and abundance to long-term application of biosolids. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 224, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ye, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, H. The variation in microbial community structure under different heavy metal contamination levels in paddy soils. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Val, C.; Barea, J.M.; Azcón-Aguilar, C. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus populations in heavy-metal-contaminated soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 718–723. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Saxena, S. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) from Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils: Molecular Approach and Application in Phytoremediation. In Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment; Giri, B., Prasad, R., Wu, Q.S., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 489–500. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Paredes, C.; López-García, Á.; Rubæk, G.H.; Hovmand, M.F.; Sørensen, P.; Kjøller, R. Risk assessment of replacing conventional P fertilizers with biomass ash: Residual effects on plant yield, nutrition, cadmium accumulation and mycorrhizal status. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ren, L.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, J.; Luo, L.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Huang, H.; Chen, A. Diagnosis of soil contamination using microbiological indices: A review on heavy metal pollution. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgason, T.; Merryweather, J.W.; Denison, J.; Wilson, P.; Young, J.P.W.; Fitter, A.H. Selectivity and functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizas of co-occurring fungi and plants from a temperate deciduous woodland. J. Ecol. 2002, 90, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douhan, G.W.; Petersen, C.; Bledsoe, C.S.; Rizzo, D.M. Contrasting root associated fungi of three common oak-woodland plant species based on molecular identification: Host specificity or non-specific amplification? Mycorrhiza 2005, 15, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.C.; Finlay, R.D.; Tehler, A. Molecular analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonising a semi-natural grassland along a fertilisation gradient. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Gonzalez, J.C.; Finlay, R.D.; Tehler, A. Seasonal dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in roots in a seminatural grassland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5613–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauregard, M.S.; Hamel, C.; Atul-Nayyar; St-Arnaud, M. Long-Term Phosphorus Fertilization Impacts Soil Fungal and Bacterial Diversity but not AM Fungal Community in Alfalfa. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 59, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Deng, Y.; Christie, P.; Murray, P.J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soil and roots respond differently to phosphorus inputs in an intensively managed calcareous agricultural soil. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.; Zucchi, M.I.; Gomes, J.E.; Tsai, S.M.; Alves-Pereira, A.; Cardoso, E.J.B.N. Araucaria angustifolia Aboveground Roots Presented High Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Colonization and Diversity in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.B.; Lee, D.J.; Dweikat, I.M.; Wedin, D.A.; Yuen, G.Y.; Drijber, R.A. Molecular Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizae in Roots of Invasive to Grasslands. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, C.S.C.; Pereira, S.I.A.; Franco, A.R.; Castro, P.M.L. Diverse Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) Communities Colonize Plants Inhabiting a Constructed Wetland for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2019, 11, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberling, J.M.; Burke, D.J. Utilizing herbarium specimens to quantify historical mycorrhizal communities. Appl. Plant Sci. 2019, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glomeromycota PHYLOGENY, Phylogeny and Taxonomy of Glomeromycota. Available online: www.amf-phylogeny.com (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- Sarathambal, C.; Khankhane, P.J.; Gharde, Y.; Kumar, B.; Varun, M.; Arun, S. The effect of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on the growth, physiology, and Cd uptake of Arundo donax L. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2017, 19, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Munar, A.; Del-Saz, N.F.; Ribas-Carbó, M.; Flexas, J.; Baraza, E.; Florez-Sarasa, I.; Fernie, A.R.; Gulías, J. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis with Arundo donax Decreases Root Respiration and Increases Both Photosynthesis and Plant Biomass Accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollastri, S.; Savvides, A.; Pesando, M.; Lumini, E.; Volpe, M.G.; Ozudogru, E.A.; Faccio, A.; De Cunzo, F.; Michelozzi, M.; Lambardi, M.; et al. Impact of two arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on Arundo donax L. response to salt stress. Planta 2018, 247, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauler, M.; Baraza, E. Improving the acclimatization and establishment of Arundo donax L. plantlets, a promising energy crop, using a mycorrhiza-based biofertilizer. Ind. Crop Prod. 2015, 66, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraza, E.; Tauler, M.; Romero-Munar, A.; Cifre, J.; Gulias, J. Mycorrhiza-Based Biofertilizer Application to Improve the Quality of Arundo donax L., Plantlets. In Perennial Biomass Crops for a Resource-Constrained World; Barth, S., Murphy-Bokern, D., Kalinina, O., Taylor, G., Jones, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, B.F.; Nicholson, F.A.; Uwakwe, N.C.; Chambers, B.J.; Harris, J.A.; Hill, T.C.J. Zinc contamination decreases the bacterial diversity of agricultural soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 43, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golui, D.; Datta, S.P.; Rattan, R.K.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Meena, M.C. Predicting bioavailability of metals from sludge-amended soils. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 8541–8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Macroelements | |||||||

| Element | SS-A | SS-B | Unit (Method) | ||||

| N | 3.47 | 3.51 | % (D) | ||||

| P | 18,129.4 | 16,663.4 | mg/kg (M) | ||||

| K | 5958.6 | 2663.4 | mg/kg (M) | ||||

| Ca | 23,694.8 | 36,394.7 | mg/kg (M) | ||||

| Mg | 5704.7 | 6444.4 | mg/kg (M) | ||||

| Microelements/Heavy Metals | |||||||

| Element | SS-A | SS-B | Unit (Method) | SS-A mg/kg Soil in 5 t/ha | SS-A mg/kg Soil in 15 t/ha | SS-B mg/kg Soil in 5 t/ha | SS-B mg/kg Soil in 15 t/ha |

| As | 8 | 3 | mg/kg (RFS) | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Cd | <2 | <1 | mg/kg (RFS) | <0.004 | <0.01 | <0.002 | <0.01 |

| Cr | 84.7 | 36 | mg/kg (RFS) | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| Cu | 654 | 224 | mg/kg (RFS) | 1.47 | 4.40 | 0.50 | 1.51 |

| Ni | 42 | 22 | mg/kg (RFS) | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| Pb | 36 | 46 | mg/kg (RFS) | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.31 |

| Zn | 1940 | 1269 | mg/kg (RFS) | 4.35 | 13.05 | 2.85 | 8.54 |

| Year | Month | Dose of SS (t/ha) | 1-λ Gini-Simpson | H Shannon | EH Evenness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 0 | 0.9286 ± 0.0542 a | 3.5022 ± 0.6170 a | 0.7599 ± 0.0671 a | |

| August | 5 | 0.9682 ± 0.0116 b | 3.9654 ± 0.3958 b | 0.8186 ± 0.0329 b | |

| 15 | 0.9652 ± 0.0141 b | 3.9435 ± 0.4920 b | 0.8135 ± 0.0454 b | ||

| 0 | 0.9582 ± 0.0154 a | 3.7126 ± 0.4006 a | 0.7864 ± 0.0387 a | ||

| November | 5 | 0.9344 ± 0.0339 ab | 3.2978 ± 0.6258 ab | 0.7577 ± 0.0526 a | |

| 15 | 0.9255 ± 0.0293 b | 3.1817 ± 0.4973 b | 0.7556 ± 0.0375 a | ||

| 2015 | 0 | 0.8702 ± 0.1355 a | 2.8653 ± 0.9912 a | 0.7581 ± 0.1126 a | |

| August | 5 | 0.8497 ± 0.1411 a | 2.6768 ± 0.8520 a | 0.7070 ± 0.1282 a | |

| 15 | 0.8131 ± 0.0954 b | 2.2390 ± 0.5040 a | 0.6827 ± 0.0792 a | ||

| 0 | 0.8484 ± 0.0696 a | 2.4569 ± 0.5780 a | 0.7043 ± 0.1075 a | ||

| December | 5 | 0.8201 ± 0.0770 a | 2.1926 ± 0.4296 a | 0.7197 ± 0.1148 a | |

| 15 | 0.8143 ± 0.0831 a | 2.1938 ± 0.5422 a | 0.7144 ± 0.0844 a |

| Similarity index | Euclidean distance | |

| Permutation N | 9999 | |

| P-value | ||

| 2014 | 2015 | |

| Dose of SS | 0.5485 | 0.1699 |

| Collection date | 0.2936 | 0.3465 |

| No. | Clone Name (GenBank ID) | GenBank ID with the Highest Similarity | GenBank Name | Similarity (%) | Phylogenetic Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1_1 (MH249155.1) | FN429371.1 | Glomus sp. | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 2 | 1_2 (MH249156.1) | KY232490.1 | Funneliformis | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 3 | 1_3 (MH249157.1) | KY232610.1 | Rhizophagus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 4 | 1_4 (MH249158.1) | EF154347.1 | Ceratobasidium | 95 | Basidiomycota |

| 5 | 1_6 (MH249159.1) | KY979295.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 6 | 1_8 (MH249160.1) | KY979397.1 | Glomus | 100 | Glomus |

| 7 | 1_20 (MH249161.1) | KJ209995.1 | Glomus | 97 | Glomeraceae |

| 8 | 1_24 (MH249162.1) | KY436352.1 | Rhizophagus irregularis | 95 | Glomeromycetes |

| 9 | 1_26 (MH249163.1) | KT291330.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 10 | 1_27 (MH249164.1) | KY232617.1 | Glomus | 96 | Glomeromycetes |

| 11 | 1_28 (MH249165.1) | KX154254.1 | Rhizophagus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 12 | 1_30 (MH249166.1) | LN715052.1 | Glomus | 93 | Glomeromycetes |

| 13 | 1_31 (MH249167.1) | KJ867233.1 | Mortierella sp. | 99 | Mortierellomycotina |

| 14 | 1_33 (MH249168.1) | HF954093.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 15 | 1_34 (MH249169.1) | MH047197.1 | Mortierella elongata | 98 | Mortierellomycotina |

| 16 | 1_35 (MH249170.1) | KY979409.1 | Glomus | 100 | Glomus |

| 17 | 1_39 (MH249171.1) | KY979298.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 18 | 1_40 (MH249172.1) | KY979360.1 | Glomus | 97 | Glomeraceae |

| 19 | 1_42 (MH249173.1) | KY979298.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 20 | 1_44 (MH249174.1) | KY979361.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 21 | 1_45 (MH249175.1) | KY232615.1 | Glomus | 97 | Glomeraceae |

| 22 | 1_47 (MH249176.1) | EU754099.1 | Pyrenochaeta cava | 86 | Ascomycota |

| 23 | 1_48 (MH249177.1) | KY232490.1 | Funneliformis | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 24 | 1_49 (MH249178.1) | KY979384.1 | Glomus | 91 | Glomeromycetes |

| 25 | 1_50 (MH249179.1) | GU353937.1 | Glomus | 89 | Glomeromycetes |

| 26 | 1_51 (MH249180.1) | KY979297.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 27 | 1_53 (MH249181.1) | LN715041.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 28 | 1_55 (MH249182.1) | KY232490.1 | Funneliformis | 97 | Glomeraceae |

| 29 | 1_56 (MH249183.1) | KC797120.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 30 | 1_58 (MH249184.1) | AB695021.1 | Glomus | 95 | Glomeromycetes |

| 31 | 1_62 (MH249185.1) | KY232617.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 32 | 1_66 (MH249186.1) | JQ218167.1 | Glomus | 96 | Glomeromycetes |

| 33 | 1_67 (MH249187.1) | EU350045.1 | Ascomycota | 97 | Ascomycota |

| 34 | 1_68 (MH249188.1) | KY979360.1 | Glomus | 90 | Glomeromycetes |

| 35 | 1_69 (MH249189.1) | KY232454.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 36 | 1_71 (MH249190.1) | JQ218180.1 | Glomus | 92 | Glomeromycetes |

| 37 | 1_72 (MH249191.1) | KY979298.1 | Glomus | 97 | Glomeraceae |

| No. | Clone Name (GenBank ID) | GenBank ID with the Highest Similarity | GenBank Name | Similarity (%) | Phylogenetic Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2_1 (MH249192.1) | EU123462.1 | Glomus | 95 | Glomeromycetes |

| 2 | 2_2 (MH249193.1) | KT291279.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 3 | 2_3 (MH249194.1) | EU350045.1 | Ascomycota | 99 | Ascomycota |

| 4 | 2_4 (MH249195.1) | KT291330.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 5 | 2_5 (MH249196.1) | AB695021.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 6 | 2_6 (MH249197.1) | JF972676.1 | Eukaryote | 99 | Eukaryota |

| 7 | 2_7 (MH249198.1) | KY232471.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 8 | 2_8 (MH249199.1) | KF186347.1 | Chaetomium | 99 | Ascomycota |

| 9 | 2_10 (MH249200.1) | KU136413.1 | Funneliformis mosseae | 90 | Glomeromycetes |

| 10 | 2_17 (MH249201.1) | KY232454.1 | Glomus | 94 | Glomeromycetes |

| 11 | 2_18 (MH249202.1) | JN788493.1 | Glomus | 94 | Glomeromycetes |

| 12 | 2_20 (MH249203.1) | KT291330.1 | Glomus | 96 | Glomeromycetes |

| 13 | 2_21 (MH249204.1) | EU622843.1 | Laetisaria arvalis | 99 | Basidiomycota |

| 14 | 2_22 (MH249205.1) | KJ209912.1 | Glomus | 93 | Glomeromycetes |

| 15 | 2_23 (MH249206.1) | FR751250.1 | Glomus mosseae | 88 | Glomeromycetes |

| 16 | 2_24 (MH249207.1) | JQ071733.1 | Chaetothyriales | 96 | Ascomycota |

| 17 | 2_25 (MH249208.1) | KY979384.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 18 | 2_28 (MH249209.1) | EU123341.1 | Ascomycota | 95 | Ascomycota |

| 19 | 2_29 (MH249210.1) | LN715042.1 | Funneliformis | 93 | Glomeromycetes |

| 20 | 2_30 (MH249211.1) | KY979384.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 21 | 2_31 (MH249212.1) | KM602163.1 | Glomeromycota | 96 | Glomeromycota |

| 22 | 2_32 (MH249213.1) | KY979384.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 23 | 2_33 (MH249214.1) | KY232497.1 | Funneliformis | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 24 | 2_34 (MH249215.1) | EU123373.1 | Basidiomycota | 96 | Basidiomycota |

| 25 | 2_35 (MH249216.1) | EU350045.1 | Ascomycota | 98 | Ascomycota |

| 26 | 2_36 (MH249217.1) | KY979355.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 27 | 2_37 (MH249218.1) | KY232438.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 28 | 2_39 (MH249219.1) | JN788427.1 | Glomus | 98 | Glomeraceae |

| 29 | 2_40 (MH249220.1) | MH047197.1 | Mortierella elongata | 93 | Mortierellomycotina |

| 30 | 2_41 (MH249221.1) | EU622843.1 | Laetisaria arvalis | 93 | Basidiomycota |

| 31 | 2_42 (MH249222.1) | KY979376.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 32 | 2_43 (MH249223.1) | KY979386.1 | Glomus | 94 | Glomeromycetes |

| 33 | 2_44 (MH249224.1) | AB698615.1 | Glomus | 88 | Glomeromycetes |

| 34 | 2_46 (MH249225.1) | EU123343.1 | Ascomycota | 97 | Ascomycota |

| 35 | 2_48 (MH249226.1) | KF186347.1 | Chaetomium | 96 | Ascomycota |

| 36 | 2_52 (MH249227.1) | KY979298.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 37 | 2_53 (MH249228.1) | KF186347.1 | Chaetomium | 99 | Ascomycota |

| 38 | 2_54 (MH249229.1) | KU707426.1 | Septoglomus | 92 | Glomeraceae |

| 39 | 2_55 (MH249230.1) | KY232615.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 40 | 2_56 (MH249231.1) | AB534478.1 | Uncultured fungus | 96 | Fungi |

| 41 | 2_57 (MH249232.1) | KT291330.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 42 | 2_58 (MH249233.1) | KY979398.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 43 | 2_59 (MH249234.1) | KF186347.1 | Chaetomium | 93 | Ascomycota |

| 44 | 2_60 (MH249235.1) | KY232519.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 45 | 2_61 (MH249236.1) | KY232519.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 46 | 2_62 (MH249237.1) | KY232454.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 47 | 2_63 (MH249238.1) | KY979355.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 48 | 2_64 (MH249239.1) | KY979355.1 | Glomus | 96 | Glomeraceae |

| 49 | 2_65 (MH249240.1) | KF186347.1 | Chaetomium | 99 | Ascomycota |

| 50 | 2_66 (MH249241.1) | KY979298.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 51 | 2_67 (MH249242.1) | KY232519.1 | Glomus | 93 | Glomeromycetes |

| 52 | 2_68 (MH249243.1) | AF202291.1 | Labyrinthomyces sp. | 95 | Ascomycota |

| 53 | 2_69 (MH249244.1) | JN788544.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 54 | 2_70 (MH249245.1) | KY979355.1 | Glomus | 99 | Glomeraceae |

| 55 | 2_71 (MH249246.1) | KY979298.1 | Glomus | 100 | Glomus |

| 56 | 2_72 (MH249247.1) | EF041057.1 | Glomus | 92 | Glomeromycetes |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ondreičková, K.; Gubišová, M.; Piliarová, M.; Horník, M.; Matušinský, P.; Gubiš, J.; Klčová, L.; Hudcovicová, M.; Kraic, J. Responses of Rhizosphere Fungal Communities to the Sewage Sludge Application into the Soil. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110505

Ondreičková K, Gubišová M, Piliarová M, Horník M, Matušinský P, Gubiš J, Klčová L, Hudcovicová M, Kraic J. Responses of Rhizosphere Fungal Communities to the Sewage Sludge Application into the Soil. Microorganisms. 2019; 7(11):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110505

Chicago/Turabian StyleOndreičková, Katarína, Marcela Gubišová, Michaela Piliarová, Miroslav Horník, Pavel Matušinský, Jozef Gubiš, Lenka Klčová, Martina Hudcovicová, and Ján Kraic. 2019. "Responses of Rhizosphere Fungal Communities to the Sewage Sludge Application into the Soil" Microorganisms 7, no. 11: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110505

APA StyleOndreičková, K., Gubišová, M., Piliarová, M., Horník, M., Matušinský, P., Gubiš, J., Klčová, L., Hudcovicová, M., & Kraic, J. (2019). Responses of Rhizosphere Fungal Communities to the Sewage Sludge Application into the Soil. Microorganisms, 7(11), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110505