Insights into Thermophilic Plant Biomass Hydrolysis from Caldicellulosiruptor Systems Biology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Maturation of Caldicellulosiruptor Genomics

2.1. Comparative Caldicellulosiruptor Genomics

2.1.1. Evolutionary Adaptations to a Strongly Cellulolytic Lifestyle

2.1.2. Diverse Mechanisms Used to Maintain Cell-Substrate Proximity

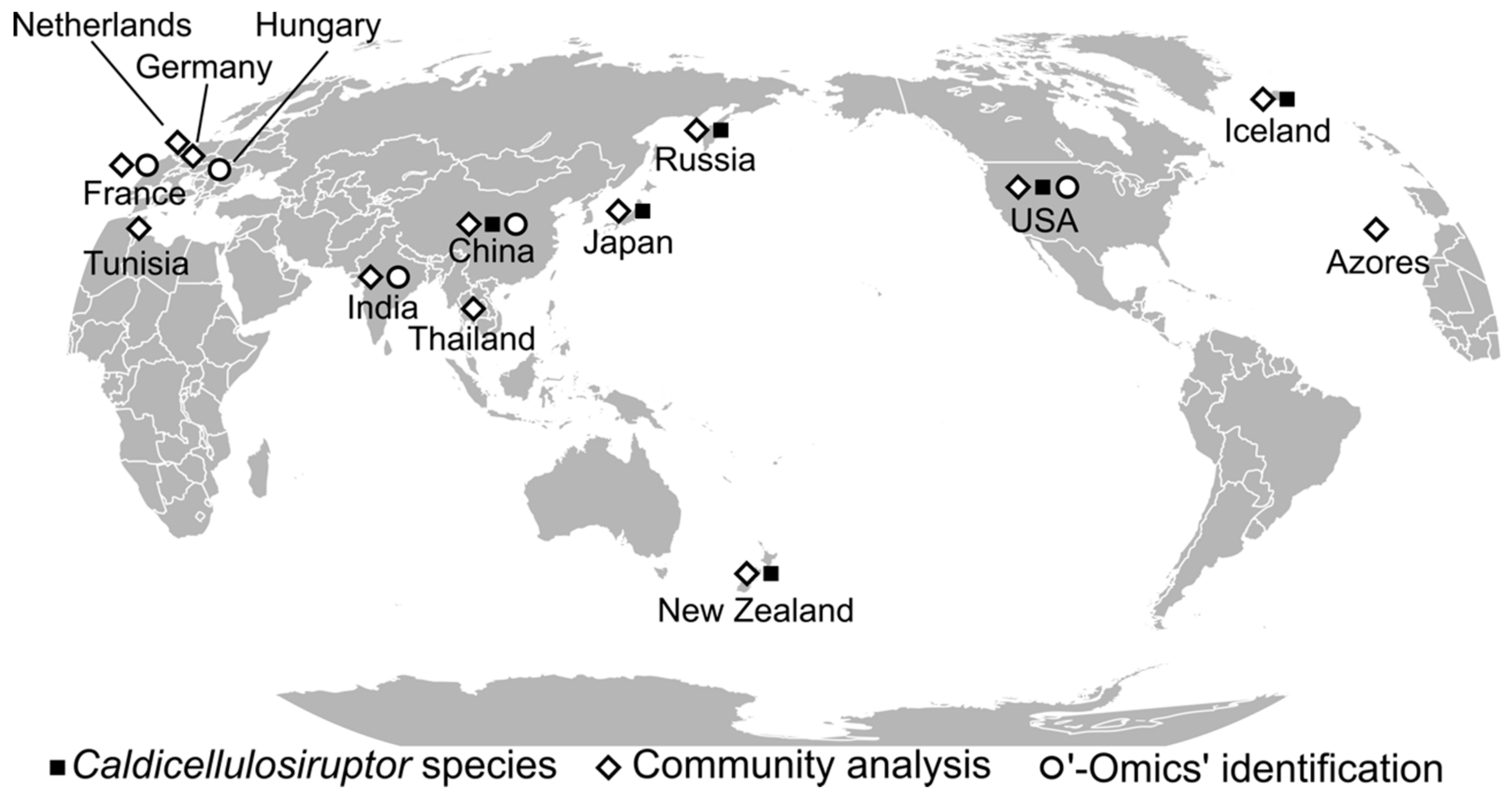

2.2. Caldicellulosiruptor Community Analyses

2.3. Caldicellulosiruptor Meta(proteo-)genomics

3. Modular Caldicellulosiruptor CAZymes

3.1. CelA

3.2. Modular Cellulase Synergy

3.3. Xylanases

3.4. Heterologous Expression of Caldicellulosiruptor Enzymes in Other Systems

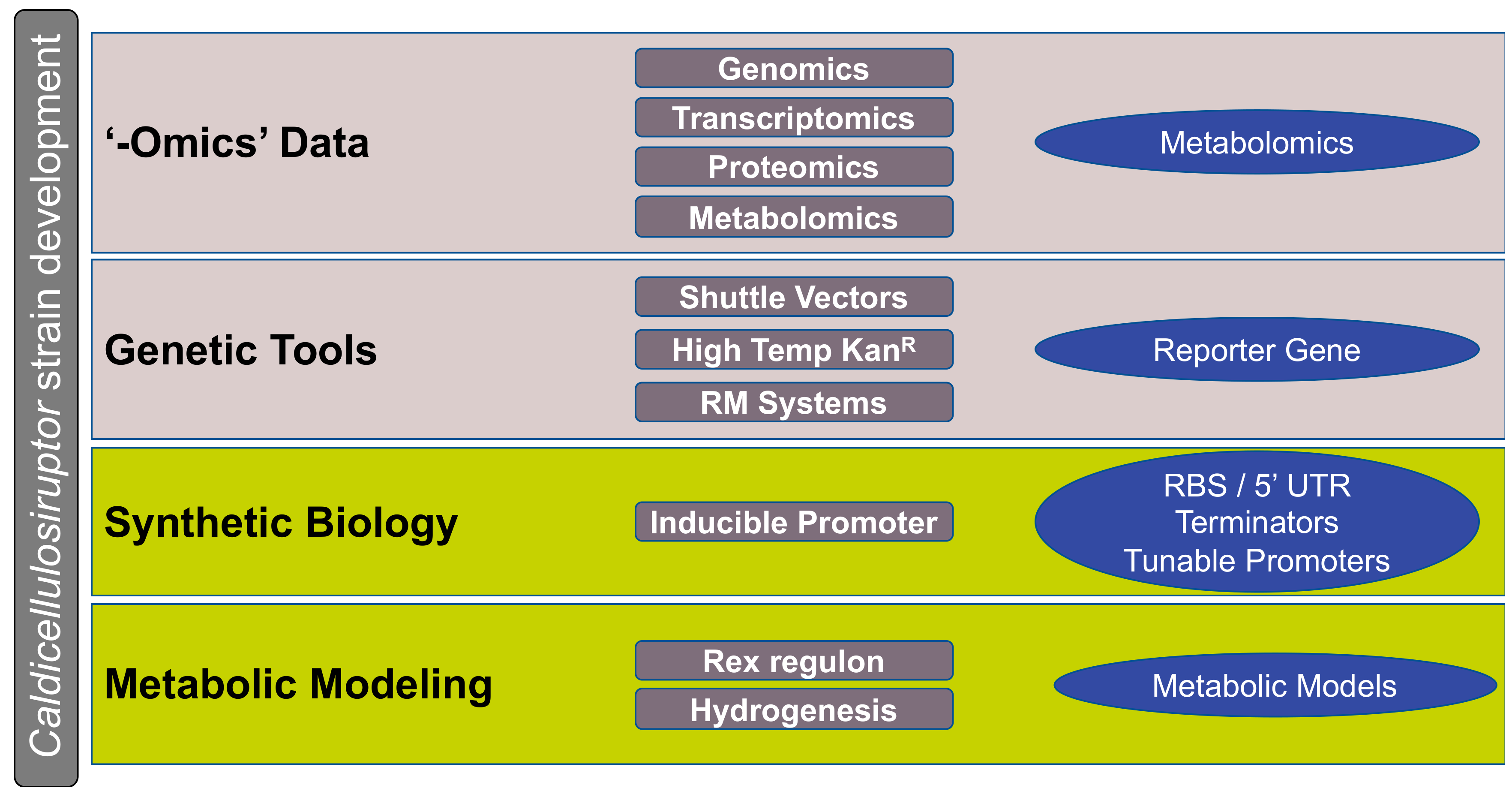

4. Caldicellulosiruptor Genetic Engineering

4.1. Metabolic Engineering

4.2. Heterologous Expression of CAZymes

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brock, T.D. Life at high temperatures. Science 1967, 158, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, J.; Mizrachi, E.; Myburg, A.A.; Cowan, D.A. Carbohydrate active enzyme domains from extreme thermophiles: Components of a modular toolbox for lignocellulose degradation. Extremophiles 2018, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Brown, S.D.; Sander, K.B.; Bayer, E.A.; Kataeva, I.; Zurawski, J.V.; Conway, J.M.; Adams, M.W.; Kelly, R.M. Thermophilic lignocellulose deconstruction. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 393–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBee, R. The characteristics of Clostridium thermocellum. J. Bacteriol. 1954, 67, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, E.A.; Kenig, R.; Lamed, R. Adherence of Clostridium thermocellum to cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 156, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamed, R.; Setter, E.; Kenig, R.; Bayer, E.A. The cellulosome—a discrete cell-surface organelle of Clostridium thermocellum. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1983, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ljungdahl, L.G.; Bryant, F.; Carreira, L.; Saiki, T.; Wiegel, J. Some aspects of thermophilic and extreme thermophilic anaerobic microorganisms. Basic Life Sci. 1981, 18, 397–419. [Google Scholar]

- Taya, M.; Hinoki, H.; Kobayashi, T. Tungsten requirement of an extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic anaerobe (strain NA10). Agric. Biol. Chem. 1985, 49, 2513–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sissons, C.H.; Sharrock, K.R.; Daniel, R.M.; Morgan, H.W. Isolation of cellulolytic anaerobic extreme thermophiles from New Zealand thermal sites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Svetlichnaya, T.P.; Chernykh, N.A.; Zavarzin, G.A. Anaerocellum thermophilum Gen. Nov Sp. Nov. an extremely thermophilic cellulolytic eubacterium isolated from hot-springs in the Valley of Geysers. Microbiology 1990, 59, 598–604. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.E.; Clark, M.E.; Nadler, D.C.; Huffer, S.; Chokhawala, H.A.; Rowland, S.E.; Blanch, H.W.; Clark, D.S.; Robb, F.T. Identification and characterization of a multidomain hyperthermophilic cellulase from an archaeal enrichment. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebl, W.; Ruile, P.; Bronnenmeier, K.; Riedel, K.; Lottspeich, F.; Greif, I. Analysis of a Thermotoga maritima DNA fragment encoding two similar thermostable cellulases, CelA and CelB, and characterization of the recombinant enzymes. Microbiology 1996, 142, 2533–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.-J.; Uegaki, K.; Fukada, H.; Ishikawa, K. Improvement of the enzymatic activity of the hyperthermophilic cellulase from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Extremophiles 2006, 11, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergquist, P.L.; Gibbs, M.D.; Morris, D.D.; Te’o, V.S.J.; Saul, D.J.; Morgan, H.W. Molecular diversity of thermophilic cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999, 28, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Werken, H.J.; Verhaart, M.R.; VanFossen, A.L.; Willquist, K.; Lewis, D.L.; Nichols, J.D.; Goorissen, H.P.; Mongodin, E.F.; Nelson, K.E.; van Niel, E.W.; et al. Hydrogenomics of the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 6720–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Stamatis, D.; Bertsch, J.; Ovchinnikova, G.; Verezemska, O.; Isbandi, M.; Thomas, A.D.; Ali, R.; Sharma, K.; Kyrpides, N.C.; et al. Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.6: Data updates and feature enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D446–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, P.; Kataeva, I.; Yang, S.-J.; Zhou, F.; Yin, Y.; Chou, W.; Poole, F.L.; Westpheling, J.; Hettich, R.; Giannone, R.; et al. Insights into plant biomass conversion from the genome of the anaerobic thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii DSM 6725. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 3240–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolshakova, E.V.; Ponomariev, A.A.; Novikov, A.A.; Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Velikodvorskaya, G.A. Cloning and expression of genes coding for carbohydrate degrading enzymes of Anaerocellum thermophilum in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 202, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zverlov, V.; Mahr, S.; Riedel, K.; Bronnenmeier, K. Properties and gene structure of a bifunctional cellulolytic enzyme (CelA) from the extreme thermophile ‘Anaerocellum thermophilum’ with separate glycosyl hydrolase family 9 and 48 catalytic domains. Microbiology 1998, 144, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te’O, V.S.J.; Saul, D.J.; Bergquist, P.L. celA, another gene coding for a multidomain cellulase from the extreme thermophile Caldocellum saccharolyticum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1995, 43, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Giannone, R.J.; Zurawski, J.V.; Ozdemir, I.; Ma, Q.; Yin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Kataeva, I.; Poole, F.L., 2nd; Adams, M.W.; et al. Caldicellulosiruptor core and pangenomes reveal determinants for noncellulosomal thermophilic deconstruction of plant biomass. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4015–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Mendoza, C.; Hauk, V.J.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E. Genomic and physiological analyses reveal that extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor changbaiensis deploys uncommon cellulose attachment mechanisms. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.L.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Izquierdo, J.A.; Zurawski, J.V.; Loder, A.J.; Conway, J.M.; Elkins, J.G.; Podar, M.; Clum, A.; Jones, P.C.; et al. Genus-wide assessment of lignocellulose utilization in the extremely thermophilic genus Caldicellulosiruptor by genomic, pangenomic, and metagenomic analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02694-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkins, J.G.; Lochner, A.; Hamilton-Brehm, S.D.; Davenport, K.W.; Podar, M.; Brown, S.D.; Land, M.L.; Hauser, L.J.; Klingeman, D.M.; Raman, B.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the cellulolytic thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis OB47T. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 6099–6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Lewis, D.L.; Kelly, R.M. Phylogenetic, microbiological, and glycoside hydrolase diversities within the extremely thermophilic, plant biomass-degrading genus Caldicellulosiruptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8084–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurawski, J.V.; Conway, J.M.; Lee, L.L.; Simpson, H.J.; Izquierdo, J.A.; Blumer-Schuette, S.; Nookaew, I.; Adams, M.W.; Kelly, R.M. Comparative analysis of extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor species reveals common and unique cellular strategies for plant biomass utilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7159–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.-D.; Ying, Y.; Zhang, K.-D.; Lu, M.; Li, F.-L. Depiction of carbohydrate-active enzyme diversity in Caldicellulosiruptor sp. F32 at the genome level reveals insights into distinct polysaccharide degradation features. Mol. Biosyst. 2015, 11, 3164–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanFossen, A.L.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; Kengen, S.M.W.; Kelly, R.M. Carbohydrate utilization patterns for the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus reveal broad growth substrate preferences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7718–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Zurawski, J.V.; Conway, J.M.; Khatibi, P.; Lewis, D.L.; Li, Q.; Chiang, V.L.; Kelly, R.M. Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus transcriptomes reveal consequences of chemical pretreatment and genetic modification of lignocellulose. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochner, A.; Giannone, R.J.; Rodriguez, M.; Shah, M.B.; Mielenz, J.R.; Keller, M.; Antranikian, G.; Graham, D.E.; Hettich, R.L. Use of label-free quantitative proteomics to distinguish the secreted cellulolytic systems of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii and Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 4042–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, M.L.; Kublanov, I.V.; Kostrikina, N.A.; Tourova, T.P.; Kolganova, T.V.; Birkeland, N.-K.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A. Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis sp. nov. and Caldicellulosiruptor hydrothermalis sp. nov., two extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic, anaerobic bacteria from Kamchatka thermal springs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 1492–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey, F.A.; Janssen, P.H.; Morgan, H.W.; Stackebrandt, E. A biphasic approach to the determination of the phenotypic and genotypic diversity of some anaerobic, cellulolytic, thermophilic, rod-shaped bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 1993, 64, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujino, T.; Beguin, P.; Aubert, J.P. Organization of a Clostridium thermocellum gene-cluster encoding the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipA and a protein possibly involved in attachment of the cellulosome to the cell-surface. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Pierce, W.S.; Le, J.H.; Harper, G.W.; Wright, J.H.; Tucker, A.L.; Zurawski, J.V.; Lee, L.L.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Kelly, R.M. Multidomain, surface layer-associated glycoside hydrolases contribute to plant polysaccharide degradation by Caldicellulosiruptor species. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 6732–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Kelly, R.M. S-layer homology domain proteins Csac_0678 and Csac_2722 are implicated in plant polysaccharide deconstruction by the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Alahuhta, M.; Conway, J.M.; Lee, L.L.; Zurawski, J.V.; Giannone, R.J.; Hettich, R.L.; Lunin, V.V.; Himmel, M.E.; Kelly, R.M. Discrete and structurally unique proteins (tāpirins) mediate attachment of extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor species to cellulose. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 10645–10656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.L.; Hart, W.S.; Lunin, V.V.; Alahuhta, M.; Bomble, Y.J.; Himmel, M.E.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Adams, M.W.W.; Kelly, R.M. Comparative biochemical and structural analysis of novel cellulose binding proteins (tāpirins) from extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 85, e01983-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.H.S.; Sissons, C.H.; Daniel, R.M.; Morgan, H.W. Comparison of cellulolytic activities in Clostridium thermocellum and three thermophilic, cellulolytic anaerobes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 51, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredholt, S.; Mathrani, I.M.; Ahring, B.K. Extremely thermophilic cellulolytic anaerobes from icelandic hot springs. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 1995, 68, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, D.R.; Fisher, R.; Bergquist, P.L. Sequence structure and expression of a cloned β-glucosidase gene from an extreme thermophile. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1988, 213, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthi, E.; Jasmat, N.B.; Grayling, R.A.; Love, D.R.; Bergquist, P.L. Cloning, sequence analysis, and expression in Escherichia coli of a gene coding for a beta-mannanase from the extremely thermophilic bacterium “Caldocellum saccharolyticum”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, M.D.; Saul, D.J.; Lüthi, E.; Bergquist, P.L. The beta-mannanase from” Caldocellum saccharolyticum” is part of a multidomain enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 3864–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, G.C.; Smith, J.J.; Cowan, D.A. Review and re-analysis of domain-specific 16S primers. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 55, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kádár, Z.; De Vrije, T.; Budde, M.; Szengyel, Z.; Réczey, K.; Claassen, P. Hydrogen production from paper sludge hydrolysate. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2003, 107, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, G.; Rákhely, G.; Kovács, K.L. Hydrogen production from biopolymers by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and stabilization of the system by immobilization. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 6953–6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrije, T.; Bakker, R.; Budde, M.; Lai, M.; Mars, A.; Claassen, P. Efficient hydrogen production from the lignocellulosic energy crop Miscanthus by the extreme thermophilic bacteria Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and Thermotoga neapolitana. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2009, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talluri, S.; Raj, S.M.; Christopher, L.P. Consolidated bioprocessing of untreated switchgrass to hydrogen by the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus DSM 8903. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 139, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahm, K.; John, P.; Nacke, H.; Wemheuer, B.; Grote, R.; Daniel, R.; Antranikian, G. High abundance of heterotrophic prokaryotes in hydrothermal springs of the Azores as revealed by a network of 16S rRNA gene-based methods. Extremophiles 2013, 17, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlygsson, J.; Sigurbjornsdottir, M.A.; Bakken, H.E. Bioprospecting thermophilic ethanol and hydrogen producing bacteria from hot springs in Iceland. Icel. Agric. Sci. 2010, 23, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kublanov, I.V.; Perevalova, A.A.; Slobodkina, G.B.; Lebedinsky, A.V.; Bidzhieva, S.K.; Kolganova, T.V.; Kaliberda, E.N.; Rumsh, L.D.; Haertle, T.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A. Biodiversity of thermophilic prokaryotes with hydrolytic activities in hot springs of Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka (Russia). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeh, R.; Birrien, J.L.; Alain, K.; Barbier, G.; Hamdi, M.; Prieur, D. Microbial diversity in Tunisian geothermal springs as detected by molecular and culture-based approaches. Extremophiles 2010, 14, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishnivetskaya, T.A.; Hamilton-Brehm, S.D.; Podar, M.; Mosher, J.J.; Palumbo, A.V.; Phelps, T.J.; Keller, M.; Elkins, J.G. Community analysis of plant biomass-degrading microorganisms from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hniman, A.; Prasertsan, P.; O-Thong, S. Community analysis of thermophilic hydrogen-producing consortia enriched from Thailand hot spring with mixed xylose and glucose. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 14217–14226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Deng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B. Characterization of a thermostable recombinant β-galactosidase from a thermophilic anaerobic bacterial consortium YTY-70. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Patel, B.K.; Mah, R.A.; Baresi, L. Caldicellulosiruptor owensensis sp. nov., an anaerobic, extremely thermophilic, xylanolytic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48 Pt 1, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Meng, D.; Chen, X.; Li, F. An extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor sp. F32 exhibits distinctive properties in growth and xylanases during xylan hydrolysis. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.S.; Wen, J.P.; Jia, X.Q. Extreme-thermophilic biohydrogen production from lignocellulosic bioethanol distillery wastewater with community analysis of hydrogen-producing microflora. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 8243–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.J.; Hinsu, A.T.; Patel, S.H.; Jakhesara, S.J.; Koringa, P.G.; Bruno, F.; Psifidi, A.; Shah, S.V.; Joshi, C.G. Microbiota composition, gene pool and its expression in Gir cattle (Bos indicus) rumen under different forage diets using metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.J.; Hinsu, A.T.; Patel, N.V.; Koringa, P.G.; Jakhesara, S.J.; Thakkar, J.R.; Shah, T.M.; Limon, G.; Psifidi, A.; Guitian, J.; et al. Microbial diversity and community composition of caecal microbiota in commercial and indigenous Indian chickens determined using 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing. Microbiome 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollo, S.M.J.; Zhaxybayeva, O.; Nesbø, C.L. Insights into thermoadaptation and the evolution of mesophily from the bacterial phylum Thermotogae. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.J.; Asakura, Y.; Kanda, K.; Fukui, R.; Kawano, Y.; Okugawa, Y.; Tashiro, Y.; Sakai, K. Dynamic bacterial community changes in the autothermal thermophilic aerobic digestion process with cell lysis activities, shaking and temperature increase. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2018, 126, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Bize, A.; Guillot, A.; Monnet, V.; Madigou, C.; Chapleur, O.; Mazeas, L.; He, P.J.; Bouchez, T. Metaproteomics of cellulose methanisation under thermophilic conditions reveals a surprisingly high proteolytic activity. ISME J. 2014, 8, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, P.D.; Gulhane, M.K.; Khardenavis, A.A.; Purohit, H.J. Mining of hemicellulose and lignin degrading genes from differentially enriched methane producing microbial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, J.-H.; Dai, K.; Ding, Z.-W.; Wang, L.-G.; Li, Q.-R.; Gao, F.-M.; Zeng, R.J. Microbial dynamics of the extreme-thermophilic (70 °C) mixed culture for hydrogen production in a chemostat. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 11072–11080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, R.; Kovács, E.; Maróti, G.; Bagi, Z.; Rákhely, G.; Kovács, K.L. Characterization of a biogas-producing microbial community by short-read next generation DNA sequencing. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlitchnyi, V.A.; Kensch, O.; Falkenhan, D.A.; Korseska, S.G.; Lippert, N.; Prinz, M.; Sassi, J.; Schickor, A.; Curvers, S. Single-step ethanol production from lignocellulose using novel extremely thermophilic bacteria. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Groenestijn, J.W.; Geelhoed, J.S.; Goorissen, H.P.; Meesters, K.P.M.; Stams, A.J.M.; Claassen, P.A.M. Performance and population analysis of a non-sterile trickle bed reactor inoculated with Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus, a thermophilic hydrogen producer. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 102, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediavilla, O.; Geml, J.; Olaizola, J.; Oria-de-Rueda, J.A.; Baldrian, P.; Martín-Pinto, P. Effect of forest fire prevention treatments on bacterial communities associated with productive Boletus edulis sites. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X.; Dong, H.L.; Jiang, H.C.; Xu, Z.Q.; Eberl, D.D. Unique microbial community in drilling fluids from Chinese continental scientific drilling. Geomicrobiol. J. 2006, 23, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, A.; Haruta, S.; McGlynn, S.E.; Thiel, V.; Matsuura, K. Nitrogen fixation in thermophilic chemosynthetic microbial communities depending on hydrogen, sulfate, and carbon dioxide. Microb. Environ. 2018, 33, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narihiro, T.; Terada, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Iguchi, A.; Ikeda, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Shiraishi, K.; Kamagata, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Sekiguchi, Y. Comparative analysis of bacterial and archaeal communities in methanogenic sludge granules from upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactors treating various food-processing, high-strength organic wastewaters. Microb. Environ. 2009, 24, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochner, A.; Giannone, R.J.; Keller, M.; Antranikian, G.; Graham, D.E.; Hettich, R.L. Label-free quantitative proteomics for the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis reveal distinct abundance patterns upon growth on cellobiose, crystalline cellulose, and switchgrass. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 5302–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, J.A.; Morgan, H.W.; Daniel, R.M. A survey of cellulolytic anaerobic thermophiles from hot springs. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1990, 13, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; McKinley, B.S.; Seals, N.L.; Hernandez, D.; Khatibi, P.A.; Poudel, S.; Giannone, R.J.; Hettich, R.L.; Williams-Rhaesa, A.M.; Lipscomb, G.L.; et al. Functional analysis of the glucan degradation locus in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii reveals essential roles of component glycoside hydrolases in plant biomass deconstruction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01828-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sota, H.; Honda, H.; Taya, M.; Iijima, S.; Kobayashi, T. Diversity of cellulases produced by a thermophilic anaerobe strain NA10. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1989, 68, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, D.J.; Williams, L.C.; Grayling, R.A.; Chamley, L.W.; Love, D.R.; Bergquist, P.L. celB, a gene coding for a bifunctional cellulase from the extreme thermophile “Caldocellum saccharolyticum”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 3117–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.D.; Reeves, R.A.; Farrington, G.K.; Anderson, P.; Williams, D.P.; Bergquist, P.L. Multidomain and multifunctional glycosyl hydrolases from the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor Isolate Tok7B.1. Curr. Microbiol. 2000, 40, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.D.; Reeves, R.A.; Gibbs, M.D.; Saul, D.J.; Bergquist, P.L. Correction of the beta-mannanase domain of the celC pseudogene from Caldocellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and activity of the gene product on kraft pulp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 2262–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Crosby, J.R.; McKinley, B.S.; Seals, N.L.; Adams, M.W.W.; Kelly, R.M. Parsing in vivo and in vitro contributions to microcrystalline cellulose hydrolysis by multidomain glycoside hydrolases in the Caldicellulosiruptor bescii secretome. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.; Su, X.; Revindran, V.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I. Molecular and Biochemical analyses of CbCel9A/Cel48A, a highly secreted multi-modular cellulase by Caldicellulosiruptor bescii during growth on crystalline cellulose. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunecky, R.; Alahuhta, M.; Xu, Q.; Donohoe, B.S.; Crowley, M.F.; Kataeva, I.A.; Yang, S.-J.; Resch, M.G.; Adams, M.W.W.; Lunin, V.V.; et al. Revealing nature’s cellulase diversity: The digestion mechanism of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii CelA. Science 2013, 342, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunecky, R.; Donohoe, B.S.; Yarbrough, J.M.; Mittal, A.; Scott, B.R.; Ding, H.; Ii, L.E.T.; Russell, J.F.; Chung, D.; Westpheling, J.; et al. The multi domain Caldicellulosiruptor bescii CelA cellulase excels at the hydrolysis of crystalline cellulose. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataeva, I.; Foston, M.B.; Yang, S.-J.; Pattathil, S.; Biswal, A.K.; Poole, F.L.; Basen, M.; Rhaesa, A.M.; Thomas, T.P.; Azadi, P.; et al. Carbohydrate and lignin are simultaneously solubilized from unpretreated switchgrass by microbial action at high temperature. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 2186–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, A.K.; Young, J.M.; Jung, S.; Chung, D.; Passian, A.; Westpheling, J.; Ragauskus, A.J. Surface Characterization of Populus during Caldicellulosiruptor bescii Growth by TOF-SIMS Analysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Chung, D.; Bomble, Y.J.; Himmel, M.E.; Westpheling, J. Deletion of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii CelA reveals its crucial role in the deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Rhaesa, A.M.; Poole, F.L.; Dinsmore, J.T.; Lipscomb, G.L.; Rubinstein, G.M.; Scott, I.M.; Conway, J.M.; Lee, L.L.; Khatibi, P.A.; Kelly, R.M.; et al. Genome stability in engineered strains of the extremely thermophilic, lignocellulose-degrading bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00444-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Chung, D.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Westpheling, J. Engineering the N-terminal end of CelA results in improved performance and growth of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii on crystalline cellulose. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunecky, R.; Chung, D.; Sarai, N.S.; Hengge, N.; Russell, J.F.; Young, J.; Mittal, A.; Pason, P.; Wall, T.V.; Michener, W.; et al. High activity CAZyme cassette for improving biomass degradation in thermophiles. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Young, J.; Bomble, Y.J.; Vander Wall, T.A.; Groom, J.; Himmel, M.E.; Westpheling, J. Homologous expression of the Caldicellulosiruptor bescii CelA reveals that the extracellular protein is glycosylated. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Sarai, N.S.; Knott, B.C.; Hengge, N.; Russell, J.F.; Yarbrough, J.M.; Brunecky, R.; Young, J.; Supekar, N.; Wall, T.V.; et al. Glycosylation is vital for industrial performance of hyperactive cellulases. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 4792–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Kim, S.-K.; Duma, J.; Nothaft, H.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Szymanski, C.M.; Westpheling, J. Deletion of a single glycosyltransferase in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii eliminates protein glycosylation and growth on crystalline cellulose. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Su, X.; Schmitz, G.E.; Moon, Y.H.; Zhang, J.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.O. Molecular and biochemical analyses of the GH44 Module of CbMan5B/Cel44A, a bifunctional enzyme from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7048–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.H.P.; Lynd, L.R. Enzyme–microbe synergy during cellulose hydrolysis by Clostridium thermocellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16165–16169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Crosby, J.R.; Hren, A.P.; Southerland, R.T.; Lee, L.L.; Lunin, V.V.; Alahuhta, P.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Adams, M.W.W.; et al. Novel multidomain, multifunctional glycoside hydrolases from highly lignocellulolytic Caldicellulosiruptor species. AIChE J. 2018, 64, 4218–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Han, Y.; Dodd, D.; Moon, Y.H.; Yoshida, S.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.O. Reconstitution of a thermostable xylan-degrading enzyme mixture from the bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Qiao, W.; Mi, S.; Jia, X.; Su, H.; Han, Y. Characterization of hemicellulase and cellulase from the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor owensensis and their potential application for bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass without pretreatment. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.J.; Han, Y.J. The extracellular endo--1,4-xylanase with multidomain from the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor lactoaceticus is specific for insoluble xylan degradation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Chung, D.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Westpheling, J. Heterologous expression of family 10 xylanases from Acidothermus cellulolyticus enhances the exoproteome of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii and growth on xylan substrates. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Artzi, L.; Bayer, E.A.; Morais, S. Cellulosomes: Bacterial nanomachines for dismantling plant polysaccharides. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, B.; Held, C.; Bergkemper, F.; Dennemarck, K.; Steinbauer, R.; Reiter, A.; Mechelke, M.; Moerch, M.; Graubner, S.; Liebl, W.; et al. Comparative characterization of all cellulosomal cellulases from Clostridium thermocellum reveals high diversity in endoglucanase product formation essential for complex activity. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, G.; Anbar, M.; Morag, E.; Lamed, R.; Bayer, E.A. Enhanced cellulose degradation by targeted integration of a cohesin-fused β-glucosidase into the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10298–10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prawitwong, P.; Waeonukul, R.; Tachaapaikoon, C.; Pason, P.; Ratanakhanokchai, K.; Deng, L.; Sermsathanaswadi, J.; Septiningrum, K.; Mori, Y.; Kosugi, A. Direct glucose production from lignocellulose using Clostridium thermocellum cultures supplemented with a thermostable β-glucosidase. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Li, R.; Hong, W.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Cui, Q.; Liu, Y.-J. Efficient whole-cell-catalyzing cellulose saccharification using engineered Clostridium thermocellum. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, B.; Li, W.; Cui, Q. The spatial proximity effect of beta-glucosidase and cellulosomes on cellulose degradation. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2018, 115, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanopoulou, A.P.; Moraïs, S.; Georgoulis, A.; Morag, E.; Bayer, E.A.; Hatzinikolaou, D.G. Insights into the functionality and stability of designer cellulosomes at elevated temperatures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 8731–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, A.; Morais, S.; Galanopoulou, A.P.; Chung, D.; Sarai, N.S.; Hengge, N.; Hatzinikolaou, D.G.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Bayer, E.A. Creation of a functional hyperthermostable designer cellulosome. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Han, D.; Xu, Z. Expression of heterologous cellulases in Thermotoga sp. strain RQ2. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2105, 304523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.I.; Steen, E.J.; Burd, H.; Evans, S.S.; Redding-Johnson, A.M.; Batth, T.; Benke, P.I.; D’haeseleer, P.; Sun, N.; Sale, K.L.; et al. A thermophilic ionic liquid-tolerant cellulase cocktail for the production of cellulosic biofuels. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campen, S.A.; Lynn, J.; Sibert, S.J.; Srikrishnan, S.; Phatale, P.; Feldman, T.; Guenther, J.M.; Hiras, J.; Tran, Y.T.A.; Singer, S.W.; et al. Expression of naturally ionic liquid-tolerant thermophilic cellulases in Aspergillus niger. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Naito, H.; Taya, M.; Iijima, S.; Kobayashi, T. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a Thermoanaerobacter cellulolyticus gene coding for heat-stable β-glucanase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1987, 25, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Saito, T.; Iijima, S.; Kobayashi, T. Isolation of a new cellulase gene from a thermophilic anaerobe and its expression in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1988, 29, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Iijima, S.; Kobayashi, T. Cloning and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of an endo-ß-glucanase gene from a thermophilic cellulolytic anaerobe. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1988, 28, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Suzuki, T.; Hayashi, A.; Honda, H.; Taya, M.; Iijima, S.; Kobayashi, T. Expression of a thermostable cellulase gene from a thermophilic anaerobe in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Ferm. Bioeng. 1990, 69, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.G.; McBride, J.E.; Joe Shaw, A.; Lynd, L.R. Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Fong, S.S. Challenges and advances for genetic engineering of non-model bacteria and uses in consolidated bioprocessing. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.-H.; Huddleston, J.; Farkas, J.; Westpheling, J. Identification and characterization of CbeI, a novel thermostable restriction enzyme from Caldicellulosiruptor bescii DSM 6725 and a member of a new subfamily of HaeIII-like enzymes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Farkas, J.; Westpheling, J. Overcoming restriction as a barrier to DNA transformation in Caldicellulosiruptor species results in efficient marker replacement. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, J.; Chung, D.; Cha, M.; Copeland, J.; Grayeski, P.; Westpheling, J. Improved growth media and culture techniques for genetic analysis and assessment of biomass utilization by Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 40, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cha, M.; Chung, D.; Elkins, J.G.; Guss, A.M.; Westpheling, J. Metabolic engineering of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii yields increased hydrogen production from lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, G.L.; Conway, J.M.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Kelly, R.M.; Adams, M.W.W. A highly thermostable kanamycin resistance marker expands the tool kit for genetic manipulation of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4421–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Cha, M.; Guss, A.M.; Westpheling, J. Direct conversion of plant biomass to ethanol by engineered Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8931–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.; Cha, M.; Farkas, J.; Westpheling, J. Construction of a stable replicating shuttle vector for Caldicellulosiruptor species: Use for extending genetic methodologies to other members of this genus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausen, A.; Mikkelsen, M.J.; Schroder, I.; Ahring, B.K. Cloning, sequencing, and sequence analysis of two novel plasmids from the thermophilic anaerobic bacterium Anaerocellum thermophilum. Plasmid 2004, 52, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, J.; Chung, D.; Olson, D.G.; Lynd, L.R.; Guss, A.M.; Westpheling, J. Promiscuous plasmid replication in thermophiles: Use of a novel hyperthermophilic replicon for genetic manipulation of Clostridium thermocellum at its optimum growth temperature. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2016, 3, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielen, A.A.M.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; van der Oost, J.; Kengen, S.W.M. Biohydrogen production by the thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus: Current status and perspectives. Life 2013, 3, 52–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkmalm, J.; Byrne, E.; van Niel, E.W.J.; Willquist, K. A non-linear model of hydrogen production by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus for diauxic-like consumption of lignocellulosic sugar mixtures. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, L.R.; Byrne, E.; van Niel, E.W.J.; Sayed, M.; Villanueva, C.C.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Hydrogen and polyhydroxybutyrate production from wheat straw hydrolysate using Caldicellulosiruptor species and Ralstonia eutropha in a coupled process. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 272, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.W.; Kelly, R.M.; Han, Y.J. Sequential processing with fermentative Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis and chemolithoautotrophic Cupriavidus necator for converting rice straw and CO2 to polyhydroxybutyrate. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Y.; Liu, S.V.; Li, G.; Huang, H.; Phelps, T.J.; Zhou, J. Isolation and characterization of metal-reducing Thermoanaerobacter strains from deep subsurface environments of the Piceance Basin, Colorado. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6013–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Rhaesa, A.M.; Rubinstein, G.M.; Scott, I.M.; Lipscomb, G.L.; Poole, I.; Farris, L.; Kelly, R.M.; Adams, M.W.W. Engineering redox-balanced ethanol production in the cellulolytic and extremely thermophilic bacterium, Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2018, 7, e00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-J.; Kataeva, I.; Wiegel, J.; Yin, Y.; Dam, P.; Xu, Y.; Westpheling, J.; Adams, M.W.W. Classification of ‘Anaerocellum thermophilum’ strain DSM 6725 as Caldicellulosiruptor bescii sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2011–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyenwoke, R.U.; Kevbrin, V.V.; Lysenko, A.M.; Wiegel, J. Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus sp. nov., a thermophilic heterotrophic anaerobe from Yellowstone National Park. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2191–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chung, D.; Cha, M.; Snyder, E.N.; Elkins, J.G.; Guss, A.M.; Westpheling, J. Cellulosic ethanol production via consolidated bioprocessing at 75 °C by engineered Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.; Verbeke, T.J.; Cross, K.L.; Westpheling, J.; Elkins, J.G. Expression of a heat-stable NADPH-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii results in furan aldehyde detoxification. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Chung, D.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Westpheling, J. Heterologous expression of a β-d-glucosidase in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii has a surprisingly modest effect on the activity of the exoproteome and growth on crystalline cellulose. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Westpheling, J. Expression of a cellobiose phosphorylase from Thermotoga maritima in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii improves the phosphorolytic pathway and results in a dramatic increase in cellulolytic activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 84, e02348-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Chung, D.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Westpheling, J. In vivo synergistic activity of a CAZyme cassette from Acidothermus cellulolyticus significantly improves the cellulolytic activity of the C. bescii exoproteome. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 2474–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Chung, D.; Himmel, M.E.; Bomble, Y.J.; Westpheling, J. Heterologous co-expression of two -glucanases and a cellobiose phosphorylase resulted in a significant increase in the cellulolytic activity of the Caldicellulosiruptor bescii exoproteome. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbarczyk, K.Z.; Mazeau, E.J.; Rapp, K.M.; Marchand, N.; Koffas, M.A.G.; Collins, C.H. Engineering Bacillus megaterium strains to secrete cellulases for synergistic cellulose degradation in a microbial community. ACS Syn. Biol. 2018, 7, 2413–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xu, C.; Li, S.; Liang, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, Z. Efficient production of lactulose from whey powder by cellobiose 2-epimerase in an enzymatic membrane reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 233, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.Y.; Cui, J.X.; Bae, H.R.; Lynd, L.R.; Olson, D.G. Expression of adhA from different organisms in Clostridium thermocellum. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basen, M.; Sun, J.S.; Adams, M.W.W. Engineering a hyperthermophilic archaeon for temperature-dependent product formation. MBio 2012, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Rhaesa, A.M.; Awuku, N.K.; Lipscomb, G.L.; Poole, F.L.; Rubinstein, G.M.; Conway, J.M.; Kelly, R.M.; Adams, M.W.W. Native xylose-inducible promoter expands the genetic tools for the biomass-degrading, extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Extremophiles 2018, 22, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, K.; Chung, D.; Hyatt, D.; Westpheling, J.; Klingeman, D.M.; Rodriguez, M.; Engle, N.L.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Davison, B.H.; Brown, S.D. Rex in Caldicellulosiruptor bescii: Novel regulon members and its effect on the production of ethanol and overflow metabolites. MicrobiologyOpen 2018, 8, e00639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing, W.; Sun, H.J.; Wang, F.M.; Song, Y.Q.; Ren, J.S. Hydrogen-producing hyperthermophilic bacteria synthesized size-controllable fine gold nanoparticles with excellence for eradicating biofilm and antibacterial applications. J. Mat. Chem. B 2018, 6, 4602–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Xia, X.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhong, Y.-C.; Zeng, R.J. Palladium nanoparticles produced and dispersed by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus enhance the degradation of contaminants in water. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 15559–15565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.-N.; Lu, Y.-Z.; Shen, N.; Lau, T.-C.; Zeng, R.J. Investigation of Cr(VI) reduction potential and mechanism by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus under glucose fermentation condition. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species Name | Genome Size (Mb) | Total ORFs | GC% | Year Sequenced | Cellulolytic Capacity | Genome Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. acetigenus | 2.59 | 2498 | 36.1 | 2013 | Weak | [23] a |

| C. bescii | 2.96 | 2905 | 35.2 | 2018 a | Strong | [17] |

| C. changbaiensis | 2.91 | 2532 | 35.1 | 2019 | Strong | [22] |

| C. danielii | 2.83 | 2731 | 35.8 | 2014 | Strong | [23] |

| C. sp. F32 | 2.38 | 2487 | 35.2 | 2013 | Strong | [27] |

| C. hydrothermalis | 2.77 | 2685 | 36.1 | 2011 | Weak | [21] |

| C. kristjanssonii | 2.8 | 2707 | 36.1 | 2011 | Weak | [21] |

| C. kronotskyensis | 2.84 | 2642 | 35.1 | 2011 | Strong | [21] |

| C. lactoaceticus | 2.67 | 2549 | 36.1 | 2011 | Moderate | [21] |

| C. morganii | 2.49 | 2407 | 36.5 | 2014 | Strong | [23] |

| C. naganoensis | 2.51 | 2436 | 35.4 | 2014 | Strong | [23] |

| C. obsidiansis | 2.53 | 2389 | 35.2 | 2011 | Strong | [24] |

| C. owensensis | 2.43 | 2322 | 35.4 | 2011 | Weak | [21] |

| C. saccharolyticus | 2.97 | 2834 | 35.3 | 2007 | Moderate | [15] |

| Country | Analysis | Origin Temperature | Source | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azores | community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated springs | [48] |

| China | community analysis | Thermophilic | Anaerobic digester sludge | [64] |

| China | community analysis | Thermophilic | Drilling fluid | [69] |

| China | community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated spring | [54] |

| China | community analysis | Mesophilic | Unknown | [57] |

| France | metaproteomics, community analysis | Thermophilic | Anaerobic digester sludge, municipal solid waste | [62] |

| Germany | community analysis | Mesophilic | soil or compost | [66] |

| Hungary | metagenomics | Mesophilic | Pig manure | [65] |

| Iceland | cellulose or xylan enrichments | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated springs | [49] |

| India | metagenomic sequencing | Unknown | Anaerobic digester sludge | [63] |

| India | metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing | Mesophilic | Gir cattle rumen | [58] |

| India | community analysis | Mesophilic | Poultry caecum | [59] |

| Japan | community analysis | Thermophilic | Thermophilic aerobic digester, human waste | [61] |

| Japan | community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated spring | [70] |

| Japan | community analysis | Mesophilic | Anaerobic sludge (upflow anaerobic sludge blanket) | [71] |

| Netherlands | community analysis | Thermophilic | Unknown | [67] |

| Thailand | community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated springs | [53] |

| Tunisia | community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated springs | [51] |

| United States | community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated spring | [52] |

| United States | metagenomic sequencing, community analysis | Thermophilic | Geothermally heated spring | [23] |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blumer-Schuette, S.E. Insights into Thermophilic Plant Biomass Hydrolysis from Caldicellulosiruptor Systems Biology. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030385

Blumer-Schuette SE. Insights into Thermophilic Plant Biomass Hydrolysis from Caldicellulosiruptor Systems Biology. Microorganisms. 2020; 8(3):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030385

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlumer-Schuette, Sara E. 2020. "Insights into Thermophilic Plant Biomass Hydrolysis from Caldicellulosiruptor Systems Biology" Microorganisms 8, no. 3: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030385

APA StyleBlumer-Schuette, S. E. (2020). Insights into Thermophilic Plant Biomass Hydrolysis from Caldicellulosiruptor Systems Biology. Microorganisms, 8(3), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030385