1. Introduction

Heat-related illness (HRI) is a potentially fatal disorder affecting man and animals, and is predicted to become more frequent as climate change increases both the severity and regularity of heatwave events [

1]. As mean annual temperatures continue to rise, human populations need to consider mitigation strategies to survive, potentially including migration away from the hottest regions [

2] or adaptations to heat including air cooling mechanisms and changes to working practices to reduce the risk of HRI to outdoor workers [

3]. Domestic dogs intertwine with every aspect of human society, from providing simple companionship to fulfilling essential working services such as hearing and visual assistant dogs, medical detection dogs and military working dogs [

4]. A deeper understanding of the risk factors for canine HRI is therefore urgently needed to ensure adaptations to rising global temperatures can include consideration of canine companions and colleagues.

From a pathophysiological perspective, HRI can be defined as hyperthermia causing progressive systemic inflammation and multi-organ dysfunction, resulting in neurological derangements and potentially death [

5]. However, this gives little information on the underlying causes of the clinical event and, more importantly, offers little information to help prevent these HRI events in the first place. From a causal perspective, two main triggers are described for HRI in humans: exertional and environmental [

5]. Exertional HRI typically follows exercise or physical labor in a hot environment or prolonged strenuous exercise in environments of any temperature [

5,

6]. Environmental HRI, also referred to as classic or non-exertional HRI, typically follows prolonged exposure to high ambient temperatures or shorter exposure to extreme heat [

7]. Very young children and babies are similar to dogs in that they are generally not agents of their own liberty from confinement [

8]. Very young children and babies are also at risk of vehicular HRI (a subtype of environmental HRI) following confinement in a hot vehicle after being left unattended or after accidentally locking themselves inside the vehicle [

8]. In human medicine, exertional HRI most commonly affects young active males either working in physically demanding industries such as construction, or participating in sports [

9]. Exertional HRI is the third leading cause of death in US high school athletes, and the incidence of HRI in the US Armed Forces has been gradually increasing since 2014 [

10]. Conversely, environmental HRI is known to typically affect socially vulnerable patients, those with advanced age or chronic medical conditions, who may be confined indoors and less resilient to natural hazards such as heatwaves [

11,

12].

Canine patients are likely to share similar risk factors to humans for the various types of HRI, but there is limited published evidence in the canine literature. Older dogs are more likely to suffer from underlying health conditions that impact thermoregulation such as heart disease [

13], which could increase the likelihood of environmental HRI [

14]. Respiratory diseases such as brachycephalic obstructive airway disorder (BOAS) have been shown to accelerate the increase in body temperature during exercise [

15] and brachycephalic dogs have intrinsically greater odds of developing HRI compared to dogs with longer muzzle [

16]. Heat regulation problems are reported to affect around a third of brachycephalic dogs [

17] and obesity has been reported as a significant risk factor for death in dogs presenting with HRI [

18]. Reflecting the male predisposition to exertional HRI in humans, male dogs develop a significantly higher body temperature than females during intense exercise [

19,

20]. Both dogs trained for military work (e.g., Belgian Malinois) and active playful dogs (e.g., Golden Retriever and Labrador Retriever) have been reported to be at increased risk of exertional HRI [

18], however, that study included only patients referred for specialist care and therefore may not represent the wider canine population. A larger primary-care study reported the Chow Chow and Bulldog with the greatest odds of HRI highlighting the value of primary-care focused research for generalization to the wider companion animal population [

21].

Because the veterinary diagnosis of HRI is heavily dependent upon an accurate history of the events leading up to the animal’s presentation [

22], greater awareness of the specific risk factors for HRI in dogs could support earlier recognition, diagnosis and appropriate management. However, prevention remains the most important approach to limiting the welfare burden of HRI overall, [

23] because irreversible organ damage and cellular destruction follow any occasion when the body is heated beyond 49 °C [

5]. Reports from Israel suggest exertional HRI may be the more common cause of heatstroke in dogs in that country [

24,

25,

26]. Although there is some evidence that exertion is also the main trigger of HRI in UK dogs [

27], current efforts to educate UK dog owners about heatstroke prevention focus almost exclusively on environmental heatstroke, specifically the message that ‘dogs die in hot cars’ [

28]. Generation of a solid evidence base on the predominant trigger of canine HRI, canine risk factors for different HRI types and the seasonality of different HRI types in the UK could support optimized and targeted educational campaigns.

This study aimed to use the VetCompass database of veterinary health records to (i) identify the leading triggers for HRI in the UK general dog population; (ii) identify risk factors for the three key triggers of HRI and (iii) compare the case fatality rate and seasonality between different HRI triggers.

4. Discussion

This is the largest primary-care study worldwide to deconstruct and explain HRI triggers in companion dogs. Reflecting the results of previous studies from Israel [

24,

25,

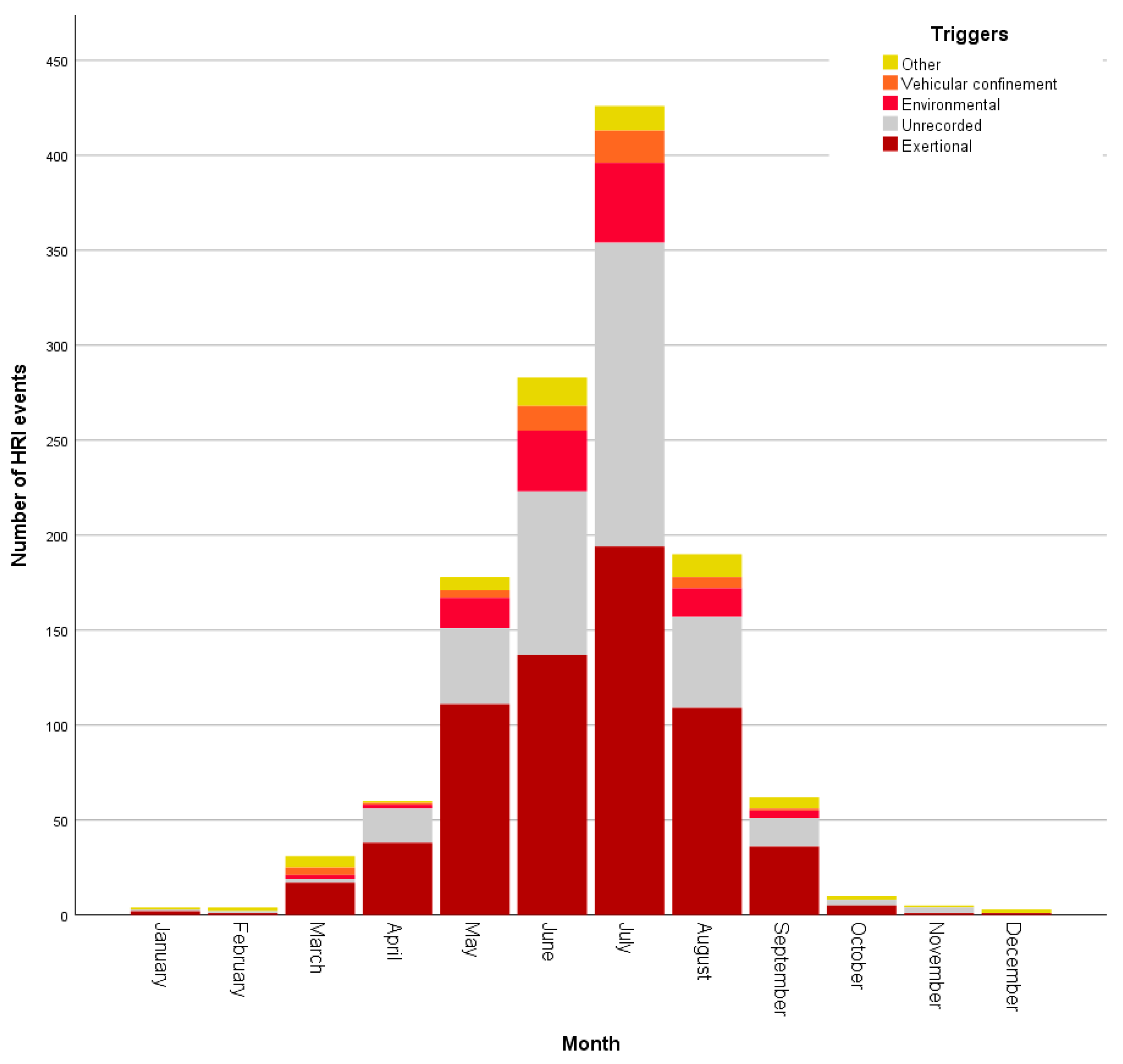

26], the predominant trigger of HRI presenting to UK primary-care practices was exertional HRI (74.2% of events with a known cause). Exertional HRI events occurred year-round, with a 7.6% overall fatality rate. Exertional HRI accounted for the majority of HRI related deaths with known triggers. The odds of death did not differ between exertional HRI, environmental HRI or vehicular HRI.

Seven breed types had greater odds of exertional HRI when compared to Labrador retrievers: Chow Chow, Bulldog, French Bulldog, Greyhound, English Springer Spaniel, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and Staffordshire Bull Terrier. Six of those breeds have previously been identified with greater odds for HRI in general [

16], whereas the Staffordshire Bull Terrier appears to have greater odds specifically for exertional HRI. The Labrador Retriever was chosen as the comparator breed for reasons highlighted previously [

16,

40] namely that the Labrador Retriever was the most common definitive breed type in the study population. However, the Labrador Retriever had twice the odds for exertional HRI compared to non-designer crossbred dogs, as did several other large active breeds (Boxer, Golden Retriever and Border Collie), along with the Pug, and “other purebred”—namely breeds with either relatively low numbers in the study population or fewer than five confirmed HRI cases. Labrador Retrievers, Golden Retrievers, Border Collies and English Springer Spaniels represent breeds that are commonly used as working or assistance/service dogs including guide dogs for the visually impaired, hearing assistance dogs, medical support dogs, military detection dogs and medical detection dogs. Given the current evidence that these breeds show increased risk of exertional HRI, it is essential that future societal adaptations to increasing ambient temperature include appropriate mitigations to safeguard working and assistance dogs.

German Shepherd Dogs showed just one-third of the odds for exertional HRI compared to the Labrador Retriever in the current study. Both Australian Shepherd Dogs [

34] and Belgian Malinois [

18] have previously been identified with increased risk of exertional HRI, however, these studies used referral hospital populations and thus likely included a relatively higher proportion of military or police working dogs than the present study based on the general population of dogs. German Shepherd Dogs and Belgian Malinois comprised over 70% of the US civilian law enforcement dogs in one study [

41], in which HRI was the second most common cause of traumatic death accounting for approximately a quarter of deaths. However, 75% of those HRI events were triggered by vehicular confinement. The conflicting findings of this study compared to previous reports suggesting an increased risk of exertional HRI in Shepherd type dogs likely reflects the difference in study populations, with the current study population being the first to explore HRI in first opinion veterinary practice. Additionally, the potential for an underlying genetic predisposition for HRI in military working dogs (Belgian Malinois) has been suggested [

42], potentially associated with low levels of expression of heat shock proteins [

43].

Exertional HRI appears to predominantly affect younger dogs, all age groups of dogs over 8 years had reduced odds compared to dogs less than 2 years of age. This may reflect differing intensity and duration of exercise undertaken by younger dogs whereas older dogs are more likely to suffer from conditions that limit their ability to exercise, such as osteoarthritis [

30] and cardiac disease [

44]. Male dogs and neutered female dogs had greater odds than entire female dogs for exertional HRI. These findings mirror the human risk factors of exertional HRI, with young male athletes and labourers most likely to be affected [

45]. Entire female dogs could have reduced odds for exertional HRI due to their relatively lower bodyweights compared to male and neutered animals [

19], or, it could reflect reduced exercise levels during reproductive periods such as pregnancy and lactation. Dogs at or above the mean adult bodyweight for their breed/sex showed an increased risk of exertional HRI compared to dogs below the mean bodyweight, and all dogs weighing 10 kg or over had increased odds of exertional HRI compared to dogs weighing under 10 kg.

Although the precise mechanisms behind the differing odds between categories for exertional HRI was not explored in this study, it is important to note that HRI is a disorder that requires extrinsic (and often human-controlled) input—dogs cannot develop HRI without exposure to a hot environment or exercise that results in overwhelming hyperthermia [

16]. Exertional HRI requires the dog to have undertaken either exercise in a hot environment [

6], or prolonged or intense exercise sufficient to exceed thermoregulatory capacity. The majority of exertional HRI events in the present study occurred following relatively low-intensity activities such as walking and occurred during the typically warmer spring and summer months. However, as demonstrated in

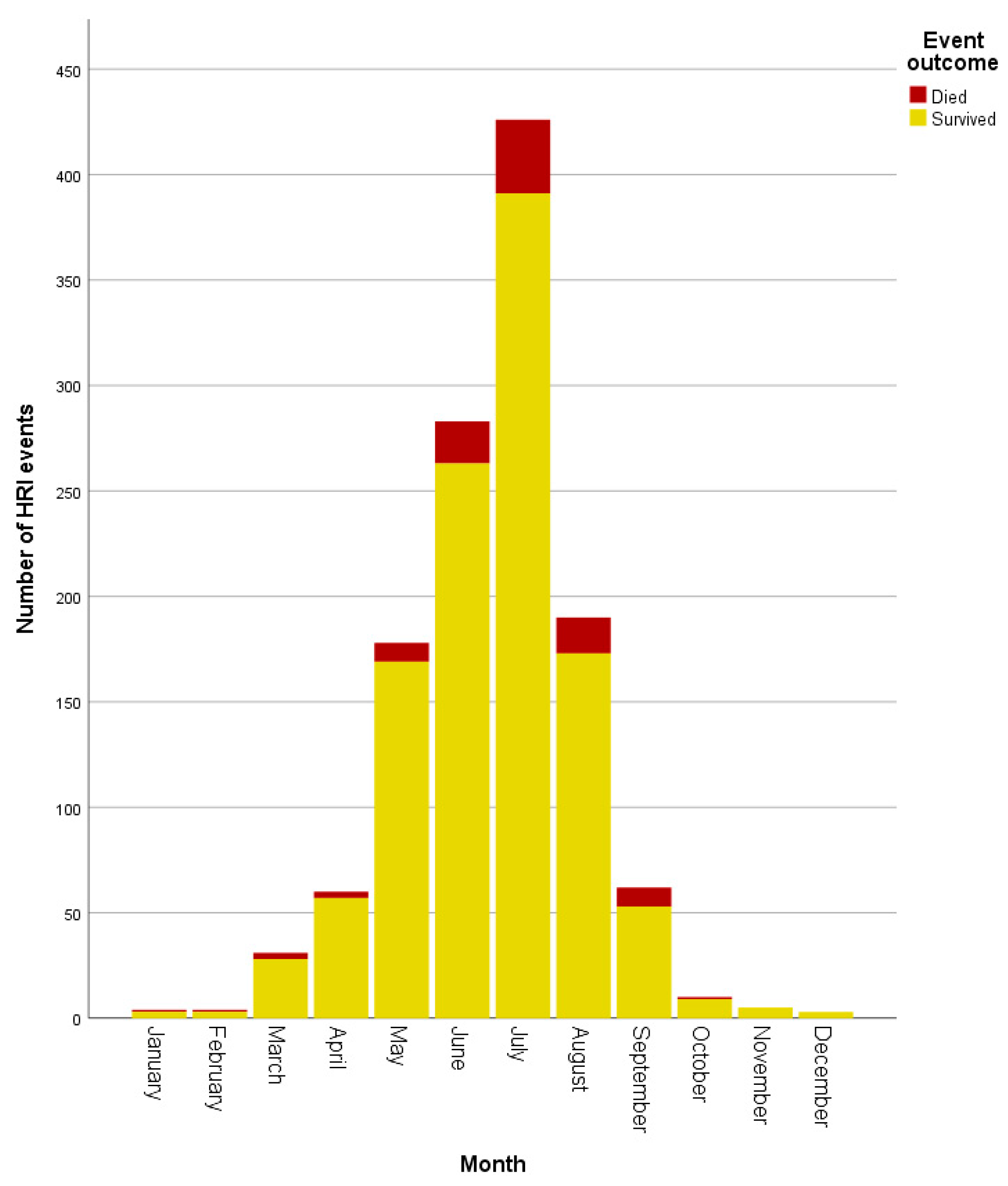

Figure 3, exertional HRI events occurred in every month (albeit with lower numbers between October and February), confirming that exertional HRI is a year-round risk for UK dogs.

Several breeds along with both non-designer crossbred and designer crossbred dogs were identified with reduced odds for HRI compared to the Labrador Retriever. Conversely, only Chihuahuas were identified with reduced odds (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.20–0.92) of exertional HRI compared to non-designer crossbred dogs. The Chihuahua is the smallest breed of dog in the world [

46], with owners reportedly more influenced by “convenience” when choosing this breed than owners of other popular dog breeds [

47]. Chihuahua ownership and popularity are also reported to be influenced by fashion and celebrity trends, with the breed frequently depicted as a “handbag dog” being carried as a fashion statement [

48]. Their relatively smaller bodyweight is likely to confer a degree of protection from HRI as previously identified [

16,

49], which could potentially be augmented by their greater likelihood of being carried than other breeds which could reduce the risk of exertional HRI due to reduced exercise.

Dogs with both dolichocephalic and brachycephalic-cross skull shapes showed reduced odds of exertional HRI, whilst brachycephalic dogs had increased odds of exertional HRI when compared to mesocephalic dogs. This gradient of increasing exertional HRI risk with shortening of the skull is likely due to the differing relative surface area of the nasal turbinates. Evaporative heat loss from panting and respiration is an important aspect of canine thermoregulation [

50], so, therefore, dogs with longer muzzles have more surface area for evaporative heat loss. The reduced odds of exertional HRI for brachycephalic-crosses is unexpected but may reflect the diversity of skull conformation types within this ill-defined category. This group is likely to be younger compared to the rest of the study population [

16], however, younger dogs have increased odds of exertional HRI. The group is also likely to have relatively lower bodyweight compared to both purebred and non-designer crossbred dogs [

16], but could also be subject to similar lifestyle differences, e.g., “handbag dogs”, as the Chihuahua due to their small stature and “designer” status.

The second most commonly reported HRI trigger was environmental (12.9% of events with a known cause). Environmental triggers were only recorded between March and September, reflecting the UK’s warmer season. The four breeds with increased odds of environmental HRI when compared to the Labrador Retriever were predominantly brachycephalic breeds (Bulldog, Pug and French Bulldog); brachycephalic dogs, in general, had 2.36 the odds compared to mesocephalic breeds. This mirrors the increased risk of environmental HRI for humans with underlying respiratory disorders, and is supported by the findings of Lilja-Maula et al. [

15] that documented Bulldogs developing hyperthermia just standing in ambient room temperature (21 °C). Although the Chow Chow had the greatest odds of both exertional and environmental HRI, it must be noted that the Chow Chow breed group was the smallest in the study population resulting in very wide confidence intervals, and so these results need to be generalized to the wider population with caution.

Dogs aged 12 years or over had over three times the odds of environmental HRI compared to dogs under 2 years, again mirroring human risk factors. Advancing age increases the likelihood of underlying health conditions such as cardiac or respiratory disease, and old age in humans has been shown to increase HRI risk due to decreased physiological thermoregulatory mechanisms such as decreased sweat production and skin blood flow [

14,

51]. Dogs weighing from 10 up to 30 kg had almost twice the odds of environmental HRI compared to dogs weighing less than 10 kg, however, interestingly none of the dogs weighing 50 kg or over were reported with environmental HRI. In general, the risk factor analysis for environmental HRI was the least informative of the three models, with the lowest R

2 and area under the ROC curve values. Environmental HRI requires prolonged exposure to a hot environment, or acute exposure to an extremely hot environment, both traditionally rare events in the UK. Environmental HRI is also the trigger for dogs that is least influenced by human behaviour, whereas both exertional HRI and vehicular HRI are heavily dependent on the actions of the dog’s owner. The much lower levels of environmental HRI compared with exertional HRI offers a substantial welfare gain opportunity by empowering owners with management tools that can limit the exertional HRI risk to their dogs. However, if climate change continues to increase, the frequency of heatwave events in the UK, the number of dogs experiencing environmental HRI is likely to increase without appropriate mitigation strategies.

Five breed types had increased odds of vehicular HRI compared to the Labrador Retriever (Bulldog, Greyhound, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, French Bulldog and Pug). Brachycephalic dogs overall had three times the odds compared to mesocephalic dogs. However, the relatively low number of vehicular HRI events (37/856) resulted in low statistical power for this analysis, as reflected in the wide confidence intervals. Only two variables remained in the final vehicular HRI risk factor model, likely reflecting the predominantly extrinsic causal structure to vehicular HRI. Any dog subjected to confinement in a hot car will overheat, as their thermoregulatory mechanisms cease to be effective once ambient temperature exceeds body temperature. Internal car temperature in the UK can exceed 50 °C between May and August, and can exceed 40 °C between April and September [

52]. The duration of confinement and the temperature within the vehicle will determine the severity of HRI [

53], however underlying canine factors that impact thermoregulatory ability (such as a respiratory compromise or disease [

50], acclimatization [

54,

55,

56] and hydration [

57]) will result in dogs overheating and developing HRI at lower relative temperatures.

Vehicular HRI was the third most common trigger and was reported only between March and September. Welfare charities and UK veterinary organisations run an annual “Dogs die in hot cars campaign”, traditionally launched around May [

58,

59]. However, Carter et al. [

52], report that internal vehicle temperatures exceeded 35 °C between the months of April and September in a study measuring UK vehicle temperatures for a two-year period. As heat acclimatization is known to impact susceptibility to HRI, sudden warm spells in March and April may be particularly dangerous for dogs left in cars. The findings of the current study, and those of Carter et al. [

52], support an earlier launch of this annual awareness campaign.

There was no significant difference in the odds for HRI related fatality between vehicular and exertional HRI. However, because exertional HRI affected around ten times as many dogs and resulted in eight times as many deaths overall than vehicular HRI, there is now a strong evidential basis to suggest that educational campaigns aimed at owners need to move from focusing purely on the risk of vehicular HRI to dogs and instead to include warnings about the more frequent dangers of exercising in hot weather.

This study identifies some important novel HRI triggers, in particular dogs developing HRI whilst under the care of veterinary practices and professional groomers. Undergoing treatment at a veterinary practice or grooming parlour was the fourth most common trigger for HRI events with a known cause, with a similar fatality rate to both exertional and vehicular HRI. This topic was explored further as part of an abstract presentation, reporting that two-thirds of the HRI events occurred in a veterinary practice (56% brachycephalic dogs) and one third whilst dogs were undergoing professional grooming (45% brachycephalic) [

27]. The French Bulldog and the Bulldog accounted for a third of the cases occurring under veterinary care, whilst West Highland White Terriers were the most numerous breed type affected during grooming. Both veterinary practice premises and grooming parlours can be warm, stressful environments for dogs, highlighting the need for careful patient monitoring and awareness of the risk of HRI in these situations, especially in predisposed breeds.

Other HRI triggers identified in the current study included building confinement and blanket entrapment. These two triggers had the highest fatalities rates, with building confinement resulting in HRI all year round. Building confinement (OR 6.1) and unrecorded trigger (OR 2.4) HRI events both had significantly greater odds for HRI fatality compared to exertional HRI. Building confinement HRI events included events where central heating had been accidentally left on, or developed a fault, and so resulted in dogs being restricted to hot environments for prolonged periods while owners were unaware of the problem. The HRI events with unrecorded triggers included emergency presentations where the attending veterinary surgeon potentially did not have time to accurately record a history in the EPR and also includes HRI events where a specific trigger was not recognised or reported by the owner. Increasing owner awareness of circumstances that can result in canine HRI should be a priority as global temperatures continue to rise.

Dogs have been proposed as an ideal translational model for studying human morbidity and mortality [

4,

60]. Domestic dogs often share their owners’ home and leisure activities including walking, running and other sports [

20]. Dogs increasingly accompany their owners to the workplace [

61] and are often included in travel and holiday plans. No other species more intimately intertwines with the human lifestyle, meaning dogs potentially face similar levels of both environmental and exertional heat exposure to humans. The results of the current study highlight that dogs share similar risk factors to humans for both exertional and environmental HRI. How dogs are transported, housed and managed will also influence HRI risk. Dogs housed outside, with no access to air conditioning or fans will be at increased risk of environmental HRI as global warming worsens. The vehicular HRI events in the current study included both dogs left in parked vehicles and dogs travelling in hot vehicles, and highlight the danger of transporting dogs in cars without adequate ventilation or air conditioning during hot weather. As the frequency of extreme weather events such as heat waves is increasing, society needs to prepare strategies to mitigate the threat of HRI [

62], to protect both human and canine health [

22].

This study had some limitations. As previously reported, the clinical record data in the VetCompass programme were not recorded primarily for research purposes, meaning there are missing data within the dataset and the accuracy of descriptive entries (such as patient histories recording HRI triggers) is reliant upon the history provided to the veterinary surgeon treating the animal and their clinical note-taking [

31,

63]. Other limitations including the lack of a definitive diagnostic test for HRI, the use of skull shape definitions such as brachycephalic and mesocephalic, and the use of manual stepwise elimination to select the final breed models for the various HRI triggers have been discussed in a previous study [

16].

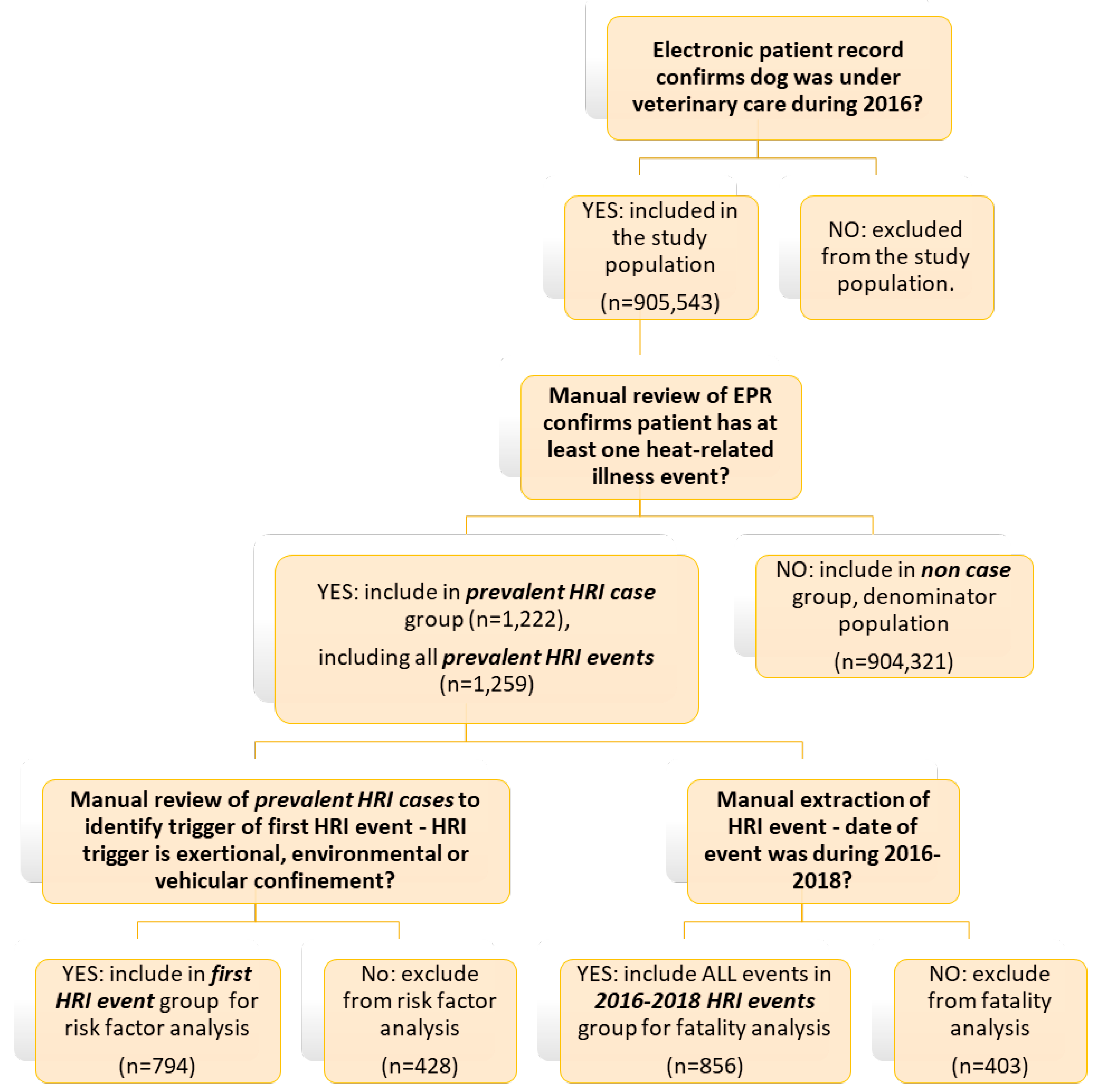

The present study used prevalent HRI events recorded at any point within the available clinical records for each dog. This may have selectively biased towards less severe HRI events, because dogs that died as a result of HRI prior to 2016 were by definition not part of the study population. This is reflected in the overall fatality rate of the prevalent cases in the present study (7.86%) which is lower than the 2016 incident fatality rate (14.18%) reported previously [

16]. As the main aims of the present study were to identify the predominant triggers for HRI in UK dogs, and explore risk factors for the top three triggers, the decision to include all prevalent HRI events was made to increase the number of events available for analysis, and thus improve the statistical power of the findings.

Finally, the present study aimed to identify potential risk factors for different HRI triggers, producing potentially explanatory models, rather than predictive models. The low R2 values for all three risk factor models highlight the impact of non-canine variables as important driving forces for HRI in dogs. The effect of ambient temperature and humidity, canine behaviour and activity status, heat acclimation, athletic fitness and overall health fitness would all need to be considered to create a truly predictive model for canine HRI. These variables are not recorded in veterinary EPRs, meaning it was not possible to include these factors in the present analysis.