Human Positioning in Close-Encounter Photographs and the Effect on Public Perceptions of Zoo Animals

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Close Encounters

1.2. Social Media

1.3. Images of Wildlife

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Selected Featured Animals

2.3. Human Position

2.4. Survey Design

- A link to a Plain Language Statement that outlined the research, participant rights, and ethics approval in more detail.

- One photograph presented per participant depicting one Featured Animal and one Human Position (for all images, see Supplementary Figure S1). The photographs were equally but randomly assigned to participants to ensure comparable sample sizes. The choice to assign only one photograph was made to reflect the work of Ross, Vreeman, and Lonsdorf [36] and Leighty et al. [37] and to remove the impact of order effects. Respondents were not informed as to which zoo these images were taken at, nor were they aware that other participants potentially saw a different image.

- A set of agreement statements measuring perceptions of zoos and the animals in the photographs:

- The animal is cared for by the zoo;

- The animal is displaying a natural behaviour;

- The animal would make a good pet.

- A set of attitude scales measuring respondents’ attitudes towards wildlife and zoos. These questions form part of a different study and the results will be reported elsewhere.

- A set of demographic questions (gender, age, level of education, residential location, zoo membership status, zoo visitation regularity, and conservation organisation membership status) to allow for the description of sample characteristics.

2.5. Sample Recruitment

- Zoo members or zoo social media followers (hereafter referred to as the Zoo Community sample), who may be more likely to post and/or see photos of close encounters. This audience is likely to be more exposed to the previous work of zoos in both welfare and conservation efforts than the general public [45], as they have made the conscious choice to receive promotional and educational materials from the zoo across their social media platforms, and thus are likely to hold an interest in zoos and animals. This sample may access such knowledge when forming attitudes based on the images they see, such as seen in Cohen [46].

- The Australian general public, members of which may also see these posts on social media, but may not be as familiar with zoos and wildlife (hereafter referred to as the General Public sample).

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.1.1. Zoo Community

3.1.2. General Public

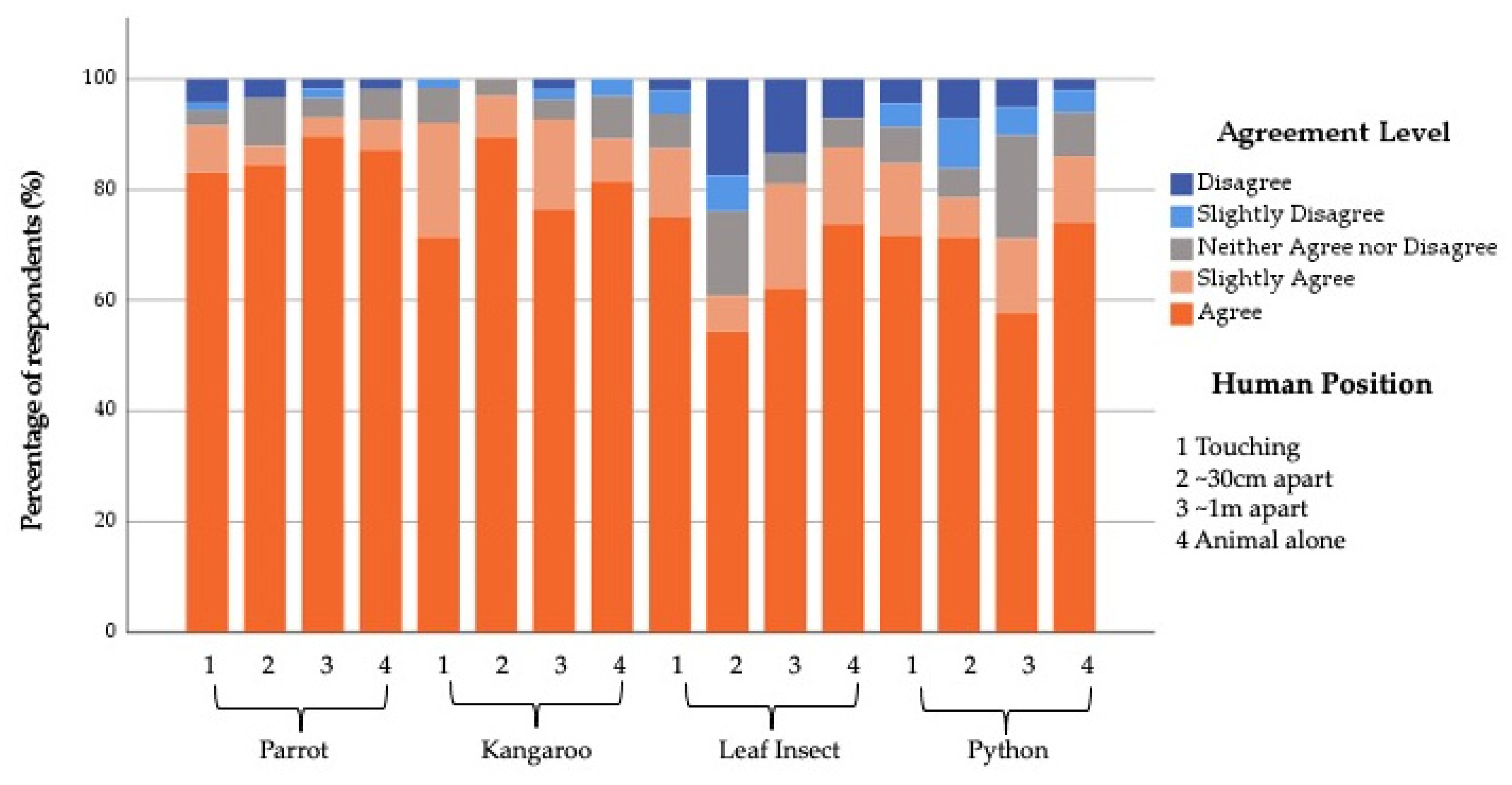

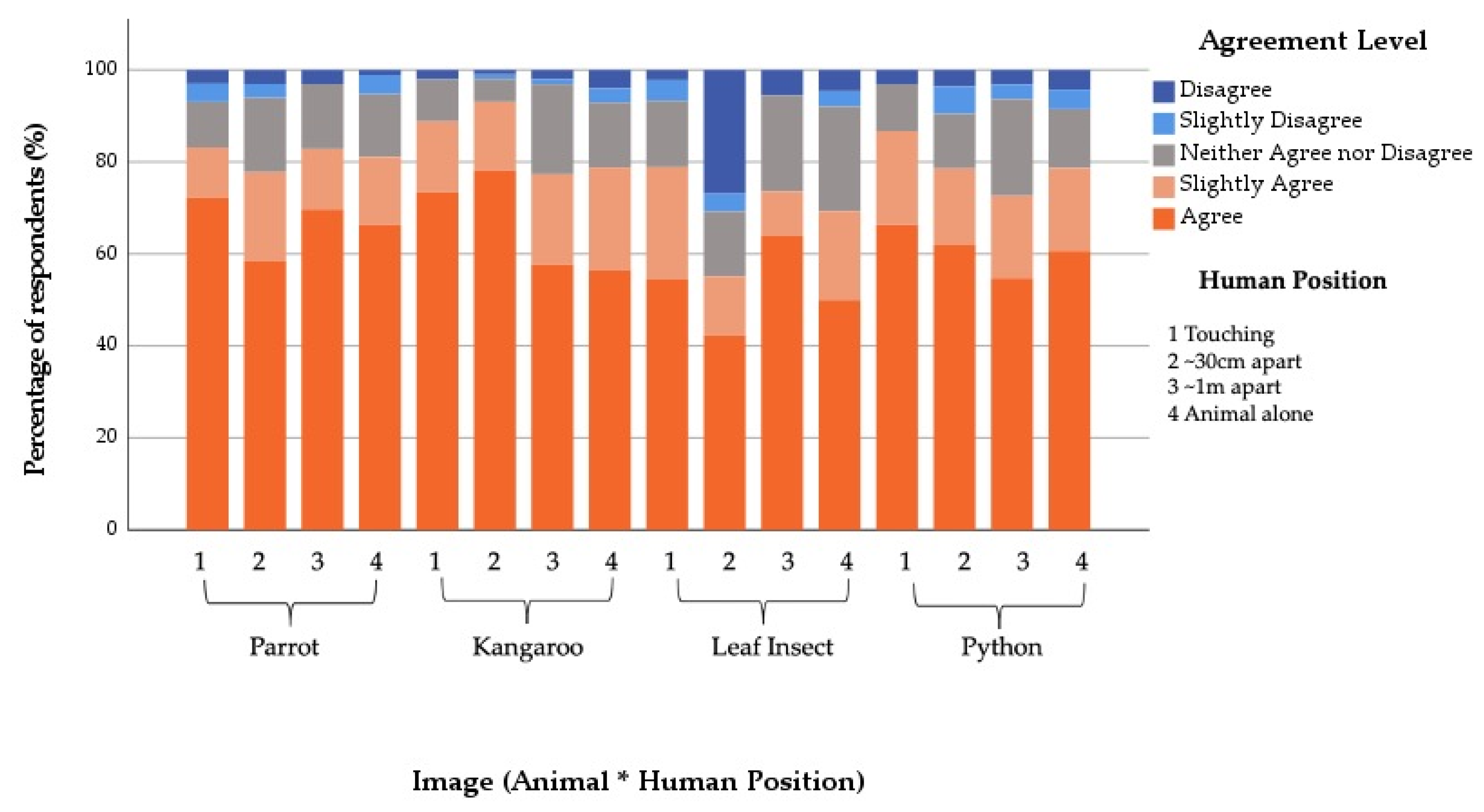

3.2. The Animal Is Cared for by the Zoo

3.2.1. Zoo Community

3.2.2. General Public

3.3. The Animal Is Displaying a Natural Behaviour

3.3.1. Zoo Community

3.3.2. General Public

3.4. The Animal Would Make a Good Pet

3.4.1. Zoo Community

3.4.2. General Public

4. Discussion

4.1. The Animal Is Cared for by the Zoo

4.2. The Animal Is Displaying a Natural Behaviour

4.3. The Animal Would Make a Good Pet

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

4.5. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, J. Zoo Ethics: The Challenges of Compassionate Conservation; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rabb, G.B.; Saunders, C.D. The future of zoos and aquariums: Conservation and caring. Int. Zoo Yearb. 2005, 39, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellish, S.; Pearson, E.L.; McLeod, E.M.; Tuckey, M.R.; Ryan, J.C. What goes up must come down: An evaluation of a zoo conservation-education program for balloon litter on visitor understanding, attitudes, and behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1393–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barongi, R.; Fisken, F.A.; Parker, M.; Gusset, M. Committing to conservation: The world zoo and aquarium conservation strategy. Gland. WAZA Exec. Off. 2015, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, O.E.; Saunders, C.D.; Birjulin, A.A. Emotional Dimensions of Watching Zoo Animals: An Experience Sampling Study Building on Insights from Psychology. Curator. Mus. J. 2004, 47, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.J.; McLeod, E.M.; Coleman, G.J. When zoo visitors “connect” with a zoo animal, what does that mean? Zoo Biol. 2019, 38, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoos and Aquariums. Code of Ethics and Animal Welfare. 2003. Available online: https://www.waza.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/WAZA-Code-of-Ethics.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Miller, L.J.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Mellen, J.; Koeppel, J.; Greer, T.; Kuczaj, S. Dolphin Shows and Interaction Programs: Benefits for Conservation Education? Zoo Biol. 2013, 32, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K.; Dierking, L. Conservation learning in wildlife tourism settings: Lessons from research in zoos and aquariums. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, K.D.; Rios, J. Using Interpretive Animals to Deliver Affective Messages in Zoos. J. Interpret. Res. 2002, 7, 19–28. Available online: https://www.m.interpnet.com/nai/docs/JIR-v7n2.pdf#page=19 (accessed on 16 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Motivational Factors and the Visitor Experience: A Comparison of Three Sites. Curator. Mus. J. 2002, 45, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosey, G.R. How does the zoo environment affect the behaviour of captive primates? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 90, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusset, M.; Mellor, D.J.; Hunt, S.; Gusset, M. Caring for wildlife: The world zoo and aquarium animal welfare strategy. WAZA Exec. Off Gland. Switz. 2015, 109, 1–87. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=20191337&site=ehost-live (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- D’Cruze, N.; Khan, S.; Carder, G.; Megson, D.; Coulthard, E.; Norrey, J.; Groves, G. A global review of animal–visitor interactions in modern zoos and aquariums and their implications for wild animal welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sherwen, S.L.; Hemsworth, P.H. The visitor effect on zoo animals: Implications and opportunities for zoo animal welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bloomfield, R.C.; Gillespie, G.R.; Kerswell, K.J.; Butler, K.L.; Hemsworth, P.H. Effect of partial covering of the visitor viewing area window on positioning and orientation of zoo orangutans: A preference test. Zoo Biol. 2015, 34, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltorai, A.E.M.; Sussman, R.W. The “Visitor Effect” and captive black-tailed prairie dog behavior. Der. Zool Garten. 2010, 79, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, P.A.; Macdonald, C.; Coleman, D. Visitor-associated variation in captive Diana monkey (Cercopithecus diana diana) behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 107, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.K.; Quirke, T.; Overy, L.; Flannery, K.; O’Riordan, R. The effect of the zoo setting on the behavioural diversity of captive gentoo penguins and the implications for their educational potential. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2016, 4, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwen, S.L.; Magrath, M.J.L.; Butler, K.L.; Phillips, C.J.C.; Hemsworth, P.H. A multi-enclosure study investigating the behavioural response of meerkats to zoo visitors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’donovan, D.; Hindle, J.; Mckeown, S.; O’donovan, S. Effect of visitors on the behaviour of female Cheetahs acinonyx jubutus and cubs. Int. Zoo Yearb. 1993, 32, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, S.W.; Hoyos, C.; Anderson, M. Effect of felid activity on zoo visitor interest. Zoo Biol. Publ. Affil. Am. Zoo Aquar. Assoc. 2003, 22, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosey, G.; Melfi, V. Anthrozoology: Human-Animal Interactions in Domesticated and Wild Animals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bracke, M.B.M.; Hopster, H. Assessing the importance of natural behavior for animal welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, H. The Natural Behavior Debate: Two Conceptions of Animal Welfare. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 23, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, G. Social Media: Communication, Sharing and Visibility; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, M. Dictionary and Thesaurus. (CD-ROM); Merriam Webster: Springfield, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nekaris, B.K.A.A.I.; Campbell, N.; Coggins, T.G.; Rode, E.J.; Nijman, V. Tickled to Death: Analysing Public Perceptions of “Cute” Videos of Threatened Species (Slow Lorises—Nycticebus spp.) on Web 2.0 Sites. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Otsuka, R.; Yamakoshi, G. Analyzing the popularity of YouTube videos that violate mountain gorilla tourism regulations. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stride, J.R.; Stride, J.R. The Mis-Advertisement of Wildlife Tourism: A Media Investigation into the Conservation Threats Facing Wildlife from Two-Shot Imagery Posted on Zoo Websites and Social Media; Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, D.; Roitman, H.; Yom-Tov, E. On the relationship between novelty and popularity of user-generated content. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2012, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Yang, Z. Measuring Emotional Contagion in Social Media. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hockley, W.E. The picture superiority effect in associative recognition. Mem. Cogn. 2008, 36, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, R.N. Recognition memory for words, sentences, and pictures. J. Verbal. Learn. Verbal. Behav. 1967, 6, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Maybery, M.T.; Durkin, K. The development of the picture-superiority effect. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 24, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.R.; Vreeman, V.M.; Lonsdorf, E.V. Specific image characteristics influence attitudes about chimpanzee conservation and use as pets. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leighty, K.A.; Valuska, A.J.; Grand, A.P.; Bettinger, T.L.; Mellen, J.D.; Ross, S.R.; Boyle, P.; Ogden, J.J. Impact of visual context on public perceptions of non-human primate performers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van der Meer, E.; Botman, S.; Eckhardt, S. I thought I saw a pussy cat: Portrayal of wild cats in friendly interactions with humans distorts perceptions and encourages interactions with wild cat species. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, S.L.; Stride, J.R. Animal-human two-shot images: Their out-of-context interpretation and the implications for zoo and conservation settings. Zoo Biol. 2021, 6, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford English Dictionary; Simpson, E.S.C.; Weiner, J.A. (Eds.) Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.J.; Tamborski, M.A.; Pickens, S.R.; Timberlake, W. Animal-visitor interactions in the modern zoo: Conflicts and interventions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbos, R.I.; Zajchowski, C.A.B.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Skibins, J.C. ‘I’d like to be just a bit closer’: Wildlife viewing proximity preferences at Denali National Park & Preserve. J. Ecotourism. 2018, 17, 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, D. Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatfelter, K.; Plucinski, K.; Project Dragonfly, M.U. Using Facebook to Promote Conservation Awareness and Action in Zoo Audiences; American Association of Zoos and Aquariums: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, C.E. Person categories and social perception: Testing some boundaries of the processing effect of prior knowledge. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Online Research Unit. About the Online Research Unit. Available online: https://www.theoru.com/about.htm (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Hays, S.P. Changing Public Attitudes. In Community and Forestry: Continuities in the Sociology of Natural Resources; Lee, R., Field, D., Burch, W., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roloff, M.E.; Miller, G.R. Persuasion: New Directions in Theory and Research; SAGE Publications, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Berry, J.K. Attitudes, Knowledge, and Behaviors toward Wildlife as Affected by Gender. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1973, 15, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. American Attitudes Toward and Knowledge of Animals: An Update. Adv. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1984 1985, 85, 177–213. [Google Scholar]

- IMB Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016.

- Sensis. 2018 Social Media Report Melbourne. 2018. Available online: https://2k5zke3drtv7fuwec1mzuxgv-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Yellow_Social_Media_Report_2020_Consumer.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Clayton, S.; Fraser, J.; Saunders, C.D. Zoo experiences: Conversations, connections, and concern for animals. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E.A.; Moss, A.; Gusset, M. Quantifying long-term impact of zoo and aquarium visits on biodiversity-related learning outcomes. Zoo Biol. 2017, 36, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ellis, L.E. Social Stratification and Socioeconomic Inequality. Reproductive and Interpersonal Aspects of Dominance and Status; Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 1994; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, B. The animals went in two by two: Heteronormativity in television wildlife documentaries. Eur. J. Cult Stud. 2013, 16, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, P. Nature documentaries: Eco-tainment? The case of MM&M (Mad Mike and Mark). Curr. Writ. 2006, 18, 146–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kilborn, R. A walk on the wild side: The changing face of TV wildlife documentary. Jump Cut. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissat, L.; Thomas-Walters, L.; Veríssimo, D. Nature documentaries as catalysts for change: Mapping out the ‘Blackfish Effect’. People Nat. 2021, 3, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D. Against Zoos. In Morality’s Progress: Essays on Humans, Other Animals, and Rest of Nature; Singer, P., Ed.; Basil Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, T.J.; Gallup, G.G.; Povinelli, D.J. Attribution of Cognitive States to Animals: Anthropomorphism in Comparative Perspective. J. Soc. Issues 1993, 49, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, S. Human attitudes towards animals in relation to species similarity to humans: A multivariate approach. Biosci. Horiz. 2009, 2, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.W. Attitudes toward Animal Use. Anthrozoos 1992, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.M. Cognitive ability and awareness in domestic animals and decisions about obligations to animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 126, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.C.; Williams, J.M.; Lawrence, A. Exploring Children’s Perspectives on the Welfare Needs of Pet Animals. Anthrozoos 2016, 29, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vrla, S.; Whitley, C.T.; Kalof, L. Inside the Yellow Rectangle: An Analysis of Nonhuman Animal Representations on National Geographic Kids Magazine Covers. Anthrozoos 2020, 33, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Values and Perceptions of Invertebrates. Conserv. Biol. 1993, 7, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceríaco, L.M.P. Human attitudes towards herpetofauna: The influence of folklore and negative values on the conservation of amphibians and reptiles in Portugal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siriwat, P.; Nijman, V. Illegal pet trade on social media as an emerging impediment to the conservation of Asian otters species. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 2018, 11, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social norms: An underestimated and underemployed lever for managing climate change. Int. J. Sustain. Commun. 2008, 3, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, R.; Ward, I. A Guide to Eclectus Parrots as Pet and Aviary Birds; ABK Publications: Burleigh, QLD, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, N. Ideal animals and animal traits for zoos: General public perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, E.; Veríssimo, D.; Keane, A.; Knight, A.T. The effectiveness of celebrities in conservation marketing. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowen-Jones, E.; Entwistle, A. Identifying appropriate flagship species: The importance of culture and local contexts. Oryx 2002, 36, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schlegel, J.; Rupf, R. Attitudes towards potential animal flagship species in nature conservation: A survey among students of different educational institutions. J. Nat. Conserv. 2010, 18, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Webber, S.; Rawson, S.; Smith, W.; Purdam, J.; McLeod, E. Virtual Reality in the Zoo: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Stereoscopic Virtual Reality Video Encounter with Little Penguins (Eudyptula minor). J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2020, 8, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Maio, G.R.; Haddock, G. The Psychology of Attitudes and Attitude Change; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, S.; Setchell, J.M.; Maréchal, L.; Oram, F.; Wallis, J.; Cheyne, S.M. Best Practice Guidelines for Responsible Images of Non-Human Primates; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Human Position | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Animal alone | The animal by itself, without human presence | A “control” to assess the difference in participant attitudes to photographs with and without human presence |

| Touching | A visible touch of the animal by the human model | To measure the impact of viewing an interaction between the human and the animal |

| ~30 cm apart | The same positioning as for touching, but without the touch interaction | To measure the impact of the human’s distance from the animal |

| ~1 m apart | The human and the animal positioned ~1 m apart | To measure the impact of the human’s distance from the animal |

| Zoo Community Sample % | General Public Sample % | Australian Public 1 % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |||

| Male | 15.4 | 49.8 | 49.6 |

| Female | 83.4 | 50 | 50.4 |

| Non-binary | 1.2 | 0.2 | >0.01 a |

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 27.8 | 10.3 | 19.3 b |

| 30–44 | 35.4 | 30.2 | 27.7 |

| 45–59 | 22.3 | 27.6 | 25.5 |

| 60–74 | 13.3 | 24.7 | 19 |

| 75+ | 1.2 | 7.1 | 8.8 |

| Residential Location | |||

| Urban | 86.2 | 87.9 | 89.9 |

| Rural | 13.8 | 12.1 | 10.1 |

| Highest Level of Education | |||

| Year 9–12 | 17.6 | 27.1 | 39.4 |

| Diploma | 11.6 | 13.8 | 24.6 |

| Undergraduate | 32.9 | 24.8 | 22 c |

| Postgraduate | 30.5 | 30.7 | |

| Doctorate | 4.8 | 1.7 | |

| Zoo/Animal Sanctuary Member | |||

| Yes | 45 | 8.1 | N/A |

| Member of Conservation Organisation | |||

| Yes | 25.8 | 7.4 | N/A |

| Frequency of Zoo Visits | |||

| Regularly (more than once a month) Sometimes (once every few months) Not very often (once or twice in the past 12 months) Not in the past 12 months Never | 9.6 27 32.5 19.5 1.3 | 2.3 9.9 32.2 49.6 5.3 | N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A |

| 95% CI Exp(ß) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | β | Std Error | Wald | df | p | Exp(ß) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Human Position (Animal alone = reference) | Touching | −1.7 | 0.19 | 74.9 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.186 | 0.12 | 1.145 |

| ~30 cm apart | −0.7 | 0.2 | 14.59 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.475 | 0.32 | 1.38 | |

| ~1 m apart | −0.7 | 0.2 | 12.07 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 1.4 | |

| Animal (Kangaroo = reference) | Parrot | −0.029 | 0.172 | 0.029 | 1 | 0.865 | 0.97 | −0.366 | 0.307 |

| Python | 0.44 | 0.183 | 5.8 | 1 | 0.016 | 1.55 | 0.082 | 0.799 | |

| Stick Insect | 0.774 | 0.195 | 15.717 | 1 | <0.001 | 2.17 | 0.392 | 1.157 | |

| 95% CI Exp(ß) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | β | Std Error | Wald | df | p | Exp(ß) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Human Position (Animal alone = reference) | Touching | −1.62 | 0.14 | 19.09 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.71 |

| ~30 cm apart | −0.37 | 0.14 | 6.65 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.475 | 0.52 | 0.91 | |

| ~1 m apart | −0.19 | 0.14 | 1.82 | 1 | 0.178 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 1.09 | |

| Animal (Kangaroo = reference) | Parrot | 0.216 | 0.134 | 2.61 | 1 | 0.106 | 1.24 | −0.046 | 0.478 |

| Python | 0.613 | 0.139 | 19.521 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.85 | 0.341 | 0.885 | |

| Stick Insect | 0.509 | 0.142 | 12.827 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.66 | 0.23 | 0.787 | |

| 95% CI Exp(β) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | β | Std Error | Wald | df | p | Exp(β) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Human Position (Animal alone = reference) | Touching | 0.44 | 0.14 | 10.44 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.19 | 2.04 |

| ~30 cm apart | 0.35 | 0.14 | 6.34 | 1 | 0.01 | 1.42 | 1.08 | 1.86 | |

| ~1 m apart | 0.25 | 0.14 | 3.28 | 1 | 0.07 | 1.29 | 0.98 | 1.69 | |

| Animal (Kangaroo = reference) | Parrot | 1.463 | 0.136 | 115.238 | 1 | <0.001 | 4.32 | 1.196 | 1.73 |

| Python | 0.049 | 0.138 | 0.124 | 1 | 0.724 | 1.05 | −0.221 | 0.318 | |

| Stick Insect | 1.027 | 0.141 | 52.802 | 1 | <0.001 | 2.79 | 0.75 | 1.304 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaw, M.N.; McLeod, E.M.; Borrie, W.T.; Miller, K.K. Human Positioning in Close-Encounter Photographs and the Effect on Public Perceptions of Zoo Animals. Animals 2022, 12, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010011

Shaw MN, McLeod EM, Borrie WT, Miller KK. Human Positioning in Close-Encounter Photographs and the Effect on Public Perceptions of Zoo Animals. Animals. 2022; 12(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaw, Meghan N., Emily M. McLeod, William T. Borrie, and Kelly K. Miller. 2022. "Human Positioning in Close-Encounter Photographs and the Effect on Public Perceptions of Zoo Animals" Animals 12, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010011

APA StyleShaw, M. N., McLeod, E. M., Borrie, W. T., & Miller, K. K. (2022). Human Positioning in Close-Encounter Photographs and the Effect on Public Perceptions of Zoo Animals. Animals, 12(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010011