Understanding Social Dimensions in Wildlife Conservation: Multiple Stakeholder Views

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

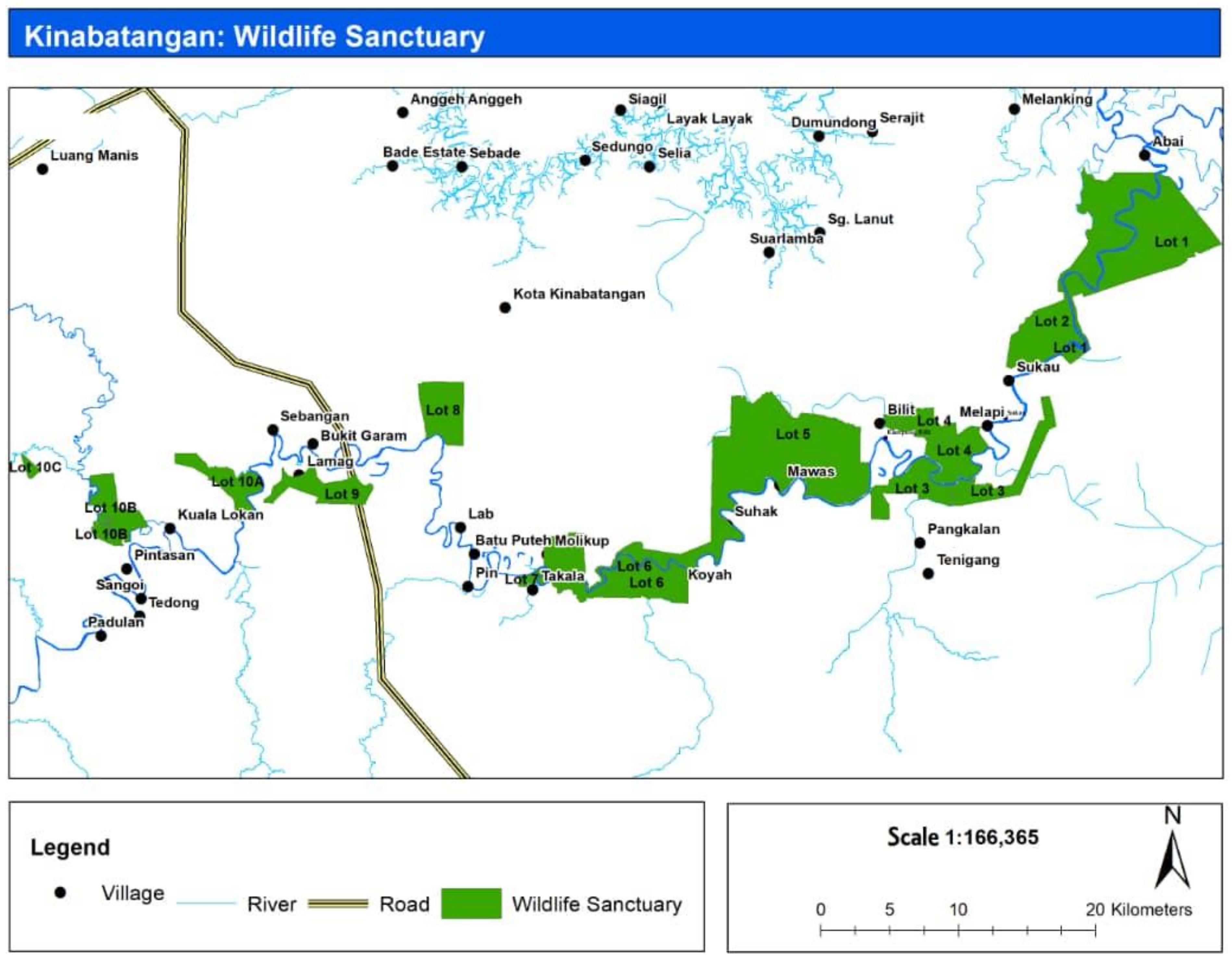

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis of Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Conservation Planning Framework

3.2. Importance of Social Integration in Solving Wildlife Conservation Issues

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sabah Wildlife Department. Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary: Wildlife Conservation and Progress; Sabah Wildlife Department: Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, J.C. Malaysia Plans Road Expansion through Dwindling Elephant, Orangutan Habitat. Mongabay News. 2016. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2016/01/malaysia-plans-road-expansion-through-dwindling-elephant-orangutan-habitat/ (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- The Guardian. David Attenborough’s ‘Guardian Headline’ Halts Borneo Bridge. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/apr/21/attenborough-guardian-headline-halts-borneo-bridge (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Ancrenaz, M.; Dabek, L.; O’Neil, S. The costs of exclusion: Recognizing a role for local communities in biodiversity conservation. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Majail, J.; Webber, D.A. Human dimension in conservation works in the Lower Kinabatangan: Sharing PFW’ s experience. In Proceedings of the Fourth Sabah-Sarawak Environmental Convention, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 5–7 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini, S.; Ferraz, K.; Zimmermann, A.; Guimarães-Luiz, T.; Morato, R.; Correa, P.L.; Macdonald, D.W. Planning for coexistence in a complex human-dominated world. In Human–Wildlife Interactions: Turning Conflict into Coexistence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 414–438. [Google Scholar]

- Redpath, S.M.; Young, J.; Evely, A.; Adams, W.M.; Sutherland, W.J.; Whitehouse, A.; Amar, A.; Lambert, R.A.; Linnell, J.D.; Watt, A. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, F. Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife: Global perspectives on local efforts to address human–wildlife conflict. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.J., Jr.; Didham, R.K.; Banks-Leite, C.; Barlow, J.; Ewers, R.M.; Rosindell, J.; Holt, R.D.; Gonzalez, A.; Pardini, R.; Damschen, E.I. Is habitat fragmentation good for biodiversity? Biol. Conserv. 2018, 226, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newmark, W.D.; Jenkins, C.N.; Pimm, S.L.; McNeally, P.B.; Halley, J.M. Targeted habitat restoration can reduce extinction rates in fragmented forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9635–9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lubis, M.; Pusparini, W.; Prabowo, S.; Marthy, W.; Andayani, N.; Linkie, M. Unraveling the complexity of human–tiger conflicts in the Leuser Ecosystem, Sumatra. Anim. Conserv. 2020, 23, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L. Conservation in context: Toward a systems framing of decentralized governance and public participation in wildlife management. Rev. Policy Res. 2019, 36, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumi, S.; McGowan, J.; Mills, M.; Beger, M.; Bustamante, R.H.; Charles, A.; Christie, P.; Fox, M.; Garcia-Borboroglu, P.; Gelcich, S. Revisiting “success” and “failure” of marine protected areas: A conservation scientist perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M. Role of Science for Conservation—A Personal Reflection. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2019, 12, 1940082919888339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatia, S.; Redpath, S.M.; Suryawanshi, K.; Mishra, C. Beyond conflict: Exploring the spectrum of human–wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx 2020, 54, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Zhang, L.; Fu, C.; Kanga, E.M. Balancing community livelihoods and biodiversity conservation of protected areas in East Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blicharska, M.; Orlikowska, E.H.; Roberge, J.-M.; Grodzinska-Jurczak, M. Contribution of social science to large scale biodiversity conservation: A review of research about the Natura 2000 network. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 199, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.M.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Epstein, G.; Nelson, M.P.; Stedman, R.; Teel, T.L. Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thome, H. Values, sociology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Teel, T.L.; Fulton, D.; Schwartz, S.H.; Arlinghaus, R.; Oishi, S.; Uskul, A.K.; Redford, K.; Kitayama, S. Why social values cannot be changed for the sake of conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallach, A.D.; Bekoff, M.; Batavia, C.; Nelson, M.P.; Ramp, D. Summoning compassion to address the challenges of conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, T.; Ednie, A. Can intrinsic, instrumental, and relational value assignments inform more integrative methods of protected area conflict resolution? Exploratory findings from Aysén, Chile. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 18, 690–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduor, A.M. Livelihood impacts and governance processes of community-based wildlife conservation in Maasai Mara ecosystem, Kenya. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancrenaz, M. Wildlife Surveys in the Lower Kinabatangan, Year 2016–2017; HUTAN Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Program: Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, J.G.; Othman, N.; Ismail, S.; Ancrenaz, M.; Goossens, B.; Ambu, L.N.; Estes, A.B.; Palmiotto, P.A. Quantity and configuration of available elephant habitat and related conservation concerns in the Lower Kinabatangan floodplain of Sabah, Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ancrenaz, M.; Gumal, M.; Marshall, A.J.; Meijaard, E.; Wich, S.A.; Husson, S. Pongo pygmaeus, Bornean Orangutan. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Wildlife Conservation Society: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. e.T17975A123809220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonratana, R.; Cheyne, S.M.; Traeholt, C.; Nijman, V.; Supriatna, J. Nasalis larvatus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020; p. e.T14352A17945165; Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/14352/17945165 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Abram, N.K.; Ancrenaz, M. Orangutan, Oil Palm and RSPO: Recognizing the Importance of the Threatened Forests of the Lower Kinabatangan, Sabah, Malaysian Borneo; Ridge to Reef, Living Landscape Alliance, Borneo Futures, Hutan, and Land Empowerment Animals People: Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dayang Norwana, A.; Kanjappan, R.; Chin, M.; Schoneveld, G.; Potter, L.; Andriani, R. The Local Impacts of Oil Palm Expansion in Malaysia; An Assessment Based on a Case Study in Sabah State; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2011; Volume 78, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alfred, R.; Ambu, L.; Nathan, S.; Goossens, B. Current status of Asian elephants in Borneo. Gajah 2011, 35, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.M.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Chapman, M.; Díaz, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; Jax, K.; Klain, S. Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arias-Arévalo, P.; Martín-López, B.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Exploring intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values for sustainable management of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheremata, M. Listening to relational values in the era of rapid environmental change in the Inuit Nunangat. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, S. Who’s in conflict with whom? Human dimensions of the conflicts involving wildlife. In Applied Ecology and Human Dimensions in Biological Conservation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga, S.; Grande, J.M.; Marchini, S. A better understanding of human behavior, not only of ‘perceptions’, will support evidence-based decision making and help to save scavenging birds: A comment to Ballejo et al. (2020). Biol. Conserv. 2020, 250, 108747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabah Wildlife Department. Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary: Purposes, Protected Species, and Locations; Sabah Wildlife Department: Kinabatangan, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abram, N.K.; Xofis, P.; Tzanopoulos, J.; MacMillan, D.C.; Ancrenaz, M.; Chung, R.; Peter, L.; Ong, R.; Lackman, I.; Goossens, B. Synergies for improving oil palm production and forest conservation in floodplain landscapes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibson, C.B. Elaboration, generalization, triangulation, and interpretation on enhancing the value of mixed method research. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 20, 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rust, N.A.; Abrams, A.; Challender, D.W.; Chapron, G.; Ghoddousi, A.; Glikman, J.A.; Gowan, C.H.; Hughes, C.; Rastogi, A.; Said, A. Quantity does not always mean quality: The importance of qualitative social science in conservation research. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ose, S.O. Using Excel and Word to structure qualitative data. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, S.G.; Ohayon, J.L.; de Wit, L.A.; Hammond, J.; Melanson, K.L.; Moritsch, M.M.; Davenport, R.; Ruiz, D.; Keitt, B.; Holmes, N.D. Best practices: Social research methods to inform biological conservation. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azungah, T. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballejo, F.; Plaza, P.I.; Lambertucci, S.A. The conflict between scavenging birds and farmers: Field observations do not support people’s perceptions. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 248, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.K.; Morales, N.A.; Chen, B.; Soodeen, R.; Moulton, M.P.; Jain, E. Love or Loss: Effective message framing to promote environmental conservation. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2019, 18, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, L.R.; Garrard, G.E.; Bekessy, S.A.; Mills, M.; Camilleri, A.R.; Fidler, F.; Fielding, K.S.; Gordon, A.; Gregg, E.A.; Kusmanoff, A.M. Messaging matters: A systematic review of the conservation messaging literature. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimid, M.; Latip, N.A.; Marzuki, A.; Umar, M.U.; Krishnan, K.T. Stakeholder management of conservation in Lower Kinabatangan Sabah. Plan. Malays. 2020, 18, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, D.; Sadowsky, B.; Douglas, L. Conservation marketing as a tool to promote human-wildlife coexistence. In Human-wildlife Interactions: Turning Conflict into Coexistence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre, N.; Fritz, M.; Freitas, T.; de Boissezon, B.; Vandewoestijne, S. Nature-Based Solutions in the EU: Innovating with nature to address social, economic and environmental challenges. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, R. Ecotourism, local community and “Partners for Wetlands” in the Lower Kinabatangan area of Sabah: Managing conservation or conflicts? Borneo Res. Bull. 2009, 3, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, M.; García-Frapolli, E.; Porter-Bolland, L.; Montiel, S. (Dis) agreements in the management of conservation conflicts in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Environ. Conserv. 2020, 47, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, J.; Nyhus, P.J. Global patterns and trends in human–wildlife conflict compensation. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, A.S.; Lyons-White, J.; Mills, M.M.; Knight, A.T. Learning from published project failures in conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 238, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Bertzky, B.; Bastin, L.; Battistella, L.; Mandrici, A.; Dubois, G. Protected area connectivity: Shortfalls in global targets and country-level priorities. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 219, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.A.; Mascia, M.B.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Glew, L.; Lester, S.E.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Darling, E.S.; Free, C.M.; Geldmann, J. Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally. Nature 2017, 543, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G. Capacity development in protected area management. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabah Wildlife Department. Bornean Elephant Action Plan for Sabah 2020–2029. Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia. 2020. Available online: https://www.hutan.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Bornean-Elephant-State-Action-Plan-2020-2029.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Leavitt, K.; Wodahl, E.J.; Schweitzer, K. Citizen willingness to report wildlife crime. Deviant Behav. 2020, 42, 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Cardozo-Urdaneta, A.; Rodríguez-Clark, K.; Moran, L.; Ovalle, L.; Ángel Arvelo, M.; Morales-Campos, J.; Coyle, B.; Braun, M. Illegal wildlife trade networks: Finding creative opportunities for conservation intervention in challenging circumstances. Anim. Conserv. 2020, 23, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, N.A.; Marzuki, A.; Marcela, P.; Umar, M.U. The involvement of indigenous peoples in promoting conservation and sustainable tourism at Lower Kinabatangan Sabah: Common issues and challenges. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 9, 323–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, R.; Roe, D.; Dublin, H.; Booker, F. Wild Life, Wild Livelihoods: Involving Communities on Sustainable Wildlife Management and Combating Illegal Wildlife Trade; United Nations Environment Program: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thondhlana, G.; Redpath, S.M.; Vedeld, P.O.; van Eden, L.; Pascual, U.; Sherren, K.; Murata, C. Non-material costs of wildlife conservation to local people and their implications for conservation interventions. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 246, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Frequency (%) N = 60 |

|---|---|

| CPF 1: Assessment | |

| 1. Local conservation awareness | 60 (100) |

| 2. Conservation link with tourism | 58 (97) |

| 3. Factors influence local support for conservation | |

| (a) Employment in conservation or tourism sector | 49 (82) |

| (b) Altruistic reason for benefit of future generation | 11 (18) |

| 4. Progress of LKWS | |

| (a) Successful | 20 (33) |

| (b) Not successful | 7 (12) |

| (c) Not sure | 33 (55) |

| 5. Effectiveness of conservation programs | |

| (a) Number of animal increase | 37 (62) |

| (b) Number of animal decrease | 23 (38) |

| (c) Habitat availability increase | 19 (32) |

| (d) Habitat availability decrease | 13 (22) |

| (e) Habitat availability (not sure) | 28 (46) |

| (f) Human–wildlife conflict reduced | 42 (70) |

| CPF 2: Decision-making | |

| 1. Decision making on conservation matters (top-down) | 42 (70) |

| 2. Conflict among conservation management | 39 (65) |

| 3. Conflict between community and management | 47 (78) |

| CPF 3: Evaluation | |

| 1. Inadequate supply of technology, tools, finance, and human resources | 32 (53) |

| 2. Integrity in governance | 18 (30) |

| 3. Local mind-set and attitudes to obey rules | 40 (67) |

| 4. Community willingness to change for pro-conservation | 37 (62) |

| 5. Importance of social integration | |

| (a) Moral obligation/duties to protect wildlife | 45 (75) |

| (b) Socio-economic importance (business/employment) | 48 (80) |

| (c) Local culture and norms | 39 (65) |

| Themes | Codes | Examples of Interview Transcripts | Notes * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human–wildlife conflict | Crop damage | “Elephants do not destroy our oil palm every day. But when it happens, it causes severe economic loss.” “In my opinion, there is no compensation for the damaged crops.” | Economic loss |

| Conflict among stakeholders (Human–human conflict) | Mistrust | “There are times, we cannot rely on others for conservation… I just cannot trust them” “Have you asked [names]? Did they mention my name? | Emotions: angry, fear, and sad |

| Inefficient communication | “I have stayed here more than 40 years, but I think conservation agencies hardly listen to the villagers’ opinions” “I think we need consistent conservation activities… the volunteers also need to be acknowledged for participating in conservation programs… but I am not sure to whom we should tell this.” | Absent of interactive platform | |

| Conservation issues | Limited finance | “We are lacking budget to get appropriate conservation tools in monitoring the wildlife” “Other countries have advance tools to monitor their animals, but we are still facing difficulties to even quantify the animal population here” | Finance for acquiring appropriate monitoring tools. |

| Inadequate human resource | “There are limited number of staffs working to monitor wildlife and enforce conservation rules” | HWW assist conservation works. | |

| Competing interests | “I know it is important to protect the animals here, but the villagers also need improvement in basic infrastructure.” “Economic development should not be carried out considering its negative impacts on the animals.” | Conservation versus socio-economic development | |

| Ecological barriers | “Major conservation problems are fragmentation and habitat loss due to deforestation.” “Effective method is to reconnect the wildlife corridor (10 lots LKWS), but this is very difficult… There are oil palm estates, private lands, and villagers’ houses.” “There are villagers who own small pieces of land. How much can they contribute to wildlife corridors? They only have enough land to build their houses.” | Fragmented animal corridor Concerns of the villagers | |

| Wildlife crimes | “Despite strict penalty, poaching and killing animals still occur at several lots of LKWS.” | Snaring, encroachment | |

| Stakeholders’ perceptions of animals | Animals increase (62%) | “Conservation agencies are conducting extensive programs to protect the animals, so the animal should increase.” “Nowadays, the government has enforced additional (severe) penalty for wildlife crimes, people cannot simply hunt. So, the animals should increase in number.” | Local perceptions contradict biological survey |

| Animals decrease (38%) | “Based on my observation working in tourism, it is harder to see the animals here… I think the animal has reduced” | Local perception | |

| Stakeholders’ recommendations | Reconnect wildlife corridor | “The long term solution is to connect the fragmented 10 lots of LKWS… But we need everyone’s support to do this” “Some private owners of oil palm estates are willing to give part of their land for animal corridors.” | Support from community and private sectors |

| Encourage villagers’ participation in tourism | “The animals are important for tourism development here. But if the villagers do not benefit from tourism, it may cause reduced support for conservation.” | Tourism as incentive for conservation | |

| Social values | “We need to protect the animals so that the young generation able to see orangutan and proboscis monkey in natural habitat.” “The villagers need to feel that they are appreciated for taking part in conservation programs.” “The motivation is not all about money. Acknowledgement before and after participating in conservation activities, such as giving them certificates.” | Altruistic value, moral obligation, motivation, recognition. | |

| Culture and norm | “It is our tradition to hunt animals for livelihoods, catch fish, plant hill rice, and collect forest products… But conservation rules restrict our traditional activities.” | Traditional activities | |

| Conservation programs | “The animal population and habitat availability are not shared during awareness campaigns… these information should be made available to the villagers.” | Conservation message |

| Approaches | Objectives | Limitations | Integration of Social Elements | Proposed Solutions Based on Stakeholder Perspectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness programs | To promote public awareness and understanding of wildlife and habitat conservation. | Focus on increased knowledge rather than behavioral change. | Improve individual moral values, beliefs, and attitudes using a non-monetary type of appreciation. To promote personal compassion and tolerance towards animals. | To include scientific information of wildlife and habitat studies during conservation awareness programs. Monitor impact of educational programs on behavioral changes. |

| Electrical fences | To prevent human–wildlife conflict: loss of agricultural yield, housing damage, and killing of animals. | Difficult to install fences, and they carry high maintenance cost. Disrupt wildlife movements and creates bottlenecks, worsening conflicts in some situations. | Individual knowledge, obligations, and ethics. To encourage individual responsibility to maintain already built fences. | To build integrated electrical fences between different blocks of private land. |

| Tree-planting | Plant trees along Lower Kinabatangan River in most degraded forest areas. | Require support from the local community to carry out the project. Limited finance, tools, and human resources are a major conservation issue. | Individual moral values and attitudes To encourage local participation in habitat restoration. | The project allows villagers to earn income by selling plant seedlings to Rileaf. This initiative should be extended to include non-participant villagers. |

| Honorary Wildlife Warden (HWW) | Local community members are elected and trained by the Sabah Wildlife Department and have the legal powers to apprehend offenders. | Most appointments are individuals already working in conservation or tourism. They are not remunerated by the state. Limited numbers of HWW staff. | Individual value, knowledge, perception, and attitudes. To increase local support for conservation through a non-monetary approach. | To increase individual participation in volunteer reporting of wildlife crimes, improve compassion through certificates of acknowledgement, and reduce dependency on HWW. |

| Wildlife corridor | To reconnect fragmented animal movement routes and restore habitat. | Challenges to connect fragmented areas due to various land use activities. | Individual moral values, knowledge, and attitudes. To encourage local participation in habitat restoration, including the private sector (oil palm plantations). | To encourage strong support and participation from oil palm plantation owners in constructing wildlife corridor. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pimid, M.; Mohd Nasir, M.R.; Krishnan, K.T.; Chambers, G.K.; Ahmad, A.G.; Perijin, J. Understanding Social Dimensions in Wildlife Conservation: Multiple Stakeholder Views. Animals 2022, 12, 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070811

Pimid M, Mohd Nasir MR, Krishnan KT, Chambers GK, Ahmad AG, Perijin J. Understanding Social Dimensions in Wildlife Conservation: Multiple Stakeholder Views. Animals. 2022; 12(7):811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070811

Chicago/Turabian StylePimid, Marcela, Mohammad Rusdi Mohd Nasir, Kumara Thevan Krishnan, Geoffrey K. Chambers, A Ghafar Ahmad, and Jimli Perijin. 2022. "Understanding Social Dimensions in Wildlife Conservation: Multiple Stakeholder Views" Animals 12, no. 7: 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070811