“It’s Like Living with a Sassy Teenager!”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Owners’ Comments about Dogs between the Ages of 12 Weeks and 2 Years

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative Text Analysis: Data Preparation

2.3.2. Quantitative Text Analysis: Word Frequency and Importance Analyses

2.3.3. Quantitative Text Analysis: Sentiment Analysis

2.3.4. Qualitative Analysis: Data Coding and Thematic Analysis

2.4. Research Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

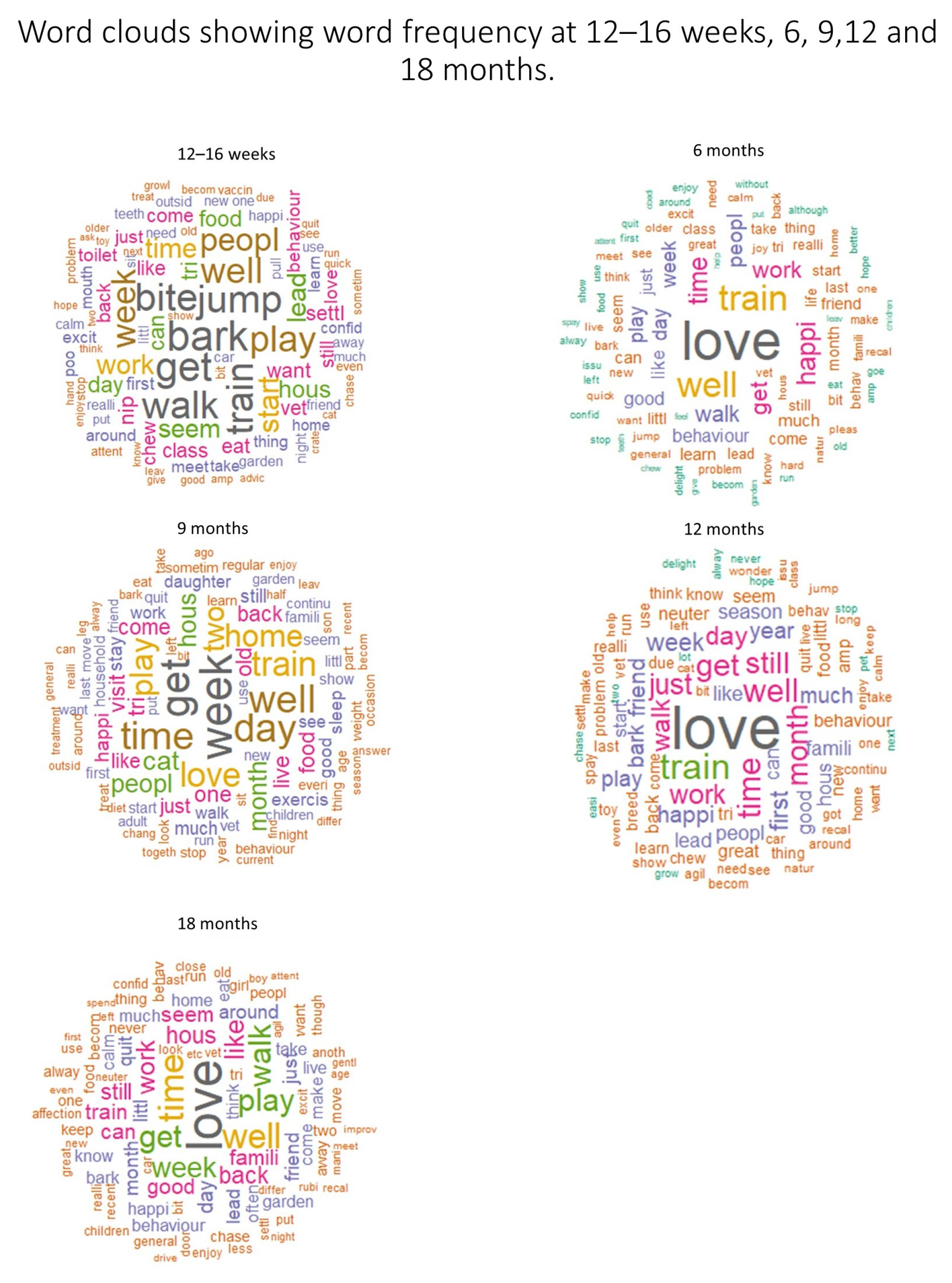

3.2. Word Frequency

3.3. Word Importance: TF-IDF

3.4. Sentiment Analysis

3.5. Qualitative Analysis

3.5.1. Explaining Dog Behaviour

3.5.2. Positive Experiences of Dog Ownership

3.5.3. Challenges of Dog Ownership

4. Discussion

4.1. Owners’ Attributions of Dog Behaviour

4.2. Change in Dog Behaviour

4.3. Positive Experiences Related to Dog Ownership

4.4. Negative Experiences Related to Dog Ownership

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hetts, S.; Clark, J.D.; Calpin, J.P.; Arnold, C.E.; Mateo, J.M. Influence of housing conditions on beagle behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1992, 34, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubrecht, R.C. A comparison of social and environmental enrichment methods for laboratory housed dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 37, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.H.; Bernadina, W.; Van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M.; De Vries, H.W.; Chronic, J.A.M. stress in dogs subjected to social and spatial restriction. II. Hormonal and immunological responses. Physiol. Behav. 1999, 66, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.H.; Van Hooff, J.A.R.A.M.; De Vries, H.W.; Mol, J.A. Behavioural and hormonal indicators of enduring environmental stress in dogs. Anim. Welf. 2000, 9, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiby, E.F.; Rooney, N.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. Behavioural and physiological responses of dogs entering re-homing kennels. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 89, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halnan, C.R.E. The frequency of occurrence of anal sacculitis in the dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1976, 17, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, C.C. A vicious cycle: A cross-sectional study of canine tail-chasing and human responses to it, using a free video-sharing website. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.D.; Hutchison, J.; Ruch-Gallie, R.; Kogan, L.; New, J.C., Jr.; Kass, P.H.; Scarlett, J.M. Behavioral Reasons for Relinquishment of Dogs and Cats to 12 Shelters. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2000, 3, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.; Slater, M.; Garrison, L.; Drain, N.; Dolan, E.; Scarlett, J.M.; Zawistowski, S.L. Large Dog Relinquishment to Two Municipal Facilities in New York City and Washington, D.C.: Identifying Targets for Intervention. Animals 2014, 4, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamonti, Z.; Zusman, N.; Cannas, S.; Minero, M.; Mazzola, S.; Palestrini, C. A description of the characteristics of dogs in, and policies of 4 shelters in, different countries. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 28, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, C.; Gray, C.; Packer, R.; Richards, Y.; Church, D.B.; Brodbelt, D.C.; O’Neill, D.G. Proportion and risk factors for death by euthanasia in dogs in the UK. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.D. Adolescence BT—Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Benedek, V.; Enz, S.; Miklósi, Á. The owners’ assessment of ‘everyday dog memory’: A questionnaire study. Interact. Stud. 2012, 13, 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, S.; Müller, C.; Virányi, Z.; Huber, L.; Range, F. Individual and group level trajectories of behavioural development in Border collies. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 180, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, L.; England, G.C.W.; Sommerville, R.; Harvey, N.D. Teenage dogs? Evidence for adolescent-phase conflict behaviour and an association between attachment to humans and pubertal timing in the domestic dog. Biol. Lett. 2020, 16, 20200097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, T.; Nagasawa, M.; Mogi, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin promotes social bonding in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9085–9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasawa, M.; Mitsui, S.; En, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science 2015, 348, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, M.S.; Casey, R.A.; Kinsman, R.H.; Tasker, S.; Knowles, T.G.; Da Costa, R.E.; Murray, J.K. Owner perception of problem behaviours in dogs aged 6 and 9-months. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 232, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.K.; Kinsman, R.H.; Lord, M.S.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Woodward, J.L.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Casey, R.A. ‘Generation Pup’—Protocol for a longitudinal study of dog behaviour and health. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Thomas, K.J. ‘Any other comments?’ Open questions on questionnaires–a bane or a bonus to research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2004, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Mohammad, S.; Turney, P. Emotions evoked by common words and phrases: Using mechanical turk to create an emotion lexicon. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Computational Approaches to Analysis and Generation of Emotion in Text, Los Angelese, CA, USA, 5 June 2010; pp. 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Feinerer, I. Introduction to the tm Package Text Mining in R. Access. en Ligne. Available online: http//cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tm/vignettes/tm.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Bouchet-Valat, M. SnowballC: Snowball Stemmers Based on the C ‘Libstemmer’UTF-8 Library (0.7.0). CRAN. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SnowballC/SnowballC.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Fellows, I. Wordcloud: Word Clouds. R Package Version 2.6. 2018. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=wordcloud (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- O’Keefe, T.; Koprinska, I. Feature selection and weighting methods in sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 14th Australasian Document Computing Symposium, Sydney, Australia, 4 December 2009; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Liu, B. Mining and summarizing customer reviews. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Seattle, WA, USA, 22–25 August 2004; pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Jockers, M. Package ‘Syuzhet’. 2007. Available online: https//cran.r-project.org/web/packages/syuzhet (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Nielsen, F.Å. A new ANEW: Evaluation of a word list for sentiment analysis in microblogs. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1103.2903. [Google Scholar]

- Grossoehme, D.; Lipstein, E. Analyzing longitudinal qualitative data: The application of trajectory and recurrent cross-sectional approaches. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Using numbers in qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can ‘thematic analysis’ offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, J. Longitudinal Qualitative Research: Analyzing Change through Time; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. Analysing qualitative longitudinal research in evaluations. Soc. Policy Soc. 2007, 6, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd (2015). NVivo (version 10) [Software Program]. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Slep, A.M.S.; O’Leary, S.G. The effects of maternal attributions on parenting: An experimental analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 1998, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colalillo, S.; Miller, N.V.; Johnston, C. Mother and father attributions for child misbehavior: Relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 34, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A. Parents’ attributions for their children’s behavior. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 1557–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.R. Excusing tactics: Social responses to the public misbehavior of companion animals. Anthrozoos 1990, 4, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, K.; Ballantyne, K.C. Living with and loving a pet with behavioral problems: Pet owners’ experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Rooney, N.; Serpell, J. Dog social behavior and communication. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People; Cambridge University Press Cambridge (UK): Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, M.S. Why Animals Matter: Animal Consciousness, Animal Welfare, and Human Well-Being; Oxford University Press (UK): Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, R.A.; Loftus, B.; Bolster, C.; Richards, G.J.; Blackwell, E.J. Human directed aggression in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Occurrence in different contexts and risk factors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.E.; Coe, J.B.; Serpell, J.A.; Pearl, D.L.; Niel, L. Risk factors associated with stranger-directed aggression in domestic dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 197, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, E.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.; Casey, R.A. Fear responses to noises in domestic dogs: Prevalence, risk factors and co-occurrence with other fear related behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 145, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, P.; Howell, T.J.; Brown, C.; Bennett, P.C. The canine cuteness effect: Owner-Perceived cuteness as a predictor of human–dog relationship quality. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, E.; Bennett, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, N.; Haney, C.J. A qualitative investigation of the significance of companion dogs. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 1175–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C. Describing the ideal Australian companion dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diverio, S.; Boccini, B.; Menchetti, L.; Bennett, P.C. The Italian perception of the ideal companion dog. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 12, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NA. Top 11 Stubborn Breeds. WAG. Available online: https://wagwalking.com/breed/top-stubborn-dog-breeds (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Ilska, J.; Haskell, M.J.; Blott, S.C.; Sánchez-Molano, E.; Polgar, Z.; Lofgren, S.E.; Wiener, P. Genetic characterization of dog personality traits. Genetics 2017, 206, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetre, P.; Strandberg, E.; Sundgren, P.; Pettersson, U.; Jazin, E.; Bergström, T.F. The genetic contribution to canine personality. Genes, Brain Behav. 2006, 5, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decorte, T.; Malm, A.; Sznitman, S.R.; Hakkarainen, P.; Barratt, M.J.; Potter, G.R.; Asmussen Frank, V. The challenges and benefits of analyzing feedback comments in surveys: Lessons from a cross-national online survey of small-scale cannabis growers. Methodol. Innov. 2019, 12, 2059799119825606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silge, J.; Robinson, D. Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Timepoint | Survey Availability and Dog’s Age | Questions Included in the Analysis | Number of Complete Responses to the Question/Sample Size at a Given Timepoint (% of Respondents Who Answered the Question) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 and 16 weeks (combined) | 12 weeks: 84–108 days | Please describe the behaviour(s) that you find to be a problem. | 1154/4427 (21.4) |

| 16 weeks: 112–136 days | Any other information? * | 998/4427 (22.5) | |

| 6 months | 180–204 days | Please describe the behaviour(s) that you find to be a problem. | 494/1788 (27.6) |

| Please use the space below to add any other information about your puppy that you would like to share with us. * | 608/1788 (34.0) | ||

| 9 months | 274–316 days | Please describe the behaviour(s) that you find to be a problem. | 467/1259 (37.1) |

| Please use the space below to add any other information about your puppy that you would like to share with us. * | 235/1259 (18.7) | ||

| 12 months | 365–407 days | Please describe the behaviour(s) that you find to be a problem. | 463/1320 (60.6) |

| Please use the space below to add any other information about your dog that you would like to share with us. * | 337/1320 (35.1) | ||

| 18 months | 547–589 days | Please describe the behaviour(s) that you find to be a problem. | 199/747 (26.6) |

| Please use the space below to add any other information about your dog that you would like to share with us. * | 138/747 (18.5) | ||

| 2 years | 730–772 days | The best thing about my dog is… | 297/302 (98.3) |

| The most annoying thing about my dog is… | 274/302 (90.7) | ||

| The funniest thing about my dog is… | 271/302 (89.7) |

| Code | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| 1. Dog’s biology | |

| a. Breed | “She is already showing characteristics of her breed such as walking to heel, sniffing out in hedgerows, following us around the house.” (12–16 weeks) “She is a typical Patterdale in that she is constantly digging holes and hunting out mice around the garden”. (9 months) “[Dog’s name] is a very excitable dog but appears quite nervous. Anxiety is a recognised issue with Vizslas.” (18 months) “Her groomer said to me, ‘you do realise that schnauzers notoriously don’t “grow up” until they’re about 3 years old don’t you!’” (2 years) |

| b. Genetics | “[Dog’s name] had settled in really well and is noted by many people as a calmer Springer. How much of this is due to genetics- her mum is an assistance dog and very calm; how much is due to nurture- we are a quiet adult only house (children have left home) ...who knows?!” (6 months) “[Clinical behaviourist] told us that it is [dog’s name], not us that is behind her anxious, aggressive behaviour. We have done everything right- tried to socialise and habituate, trying to only have positive experiences for her, took her out and about, gentle introductions etc. but she ‘resisted’ all of this- largely genetics of the breed, her mother, and early experiences.” (18 months) “Unfortunately, although she is keen to work and very stylish her breeding has made her very wide and off-contact on sheep and thesis [sic?] almost impossible to correct since dogs get wider as they get older. It is frustrating because this is a genetic fault, not a training fault.” (2 years) |

| c. Sex/hormones | “Very solid temperament to date but bitches can change so we will see”. (12–16 weeks) “Has had a 3 month first season followed by a pseudo pregnancy so has been very hormonal, excitable and clinging plus has shown aggression to our other bitch”. (9 months) “He is also peeing around the house, occasionally on the bed. (…) I think he is marking… (…) Hopefully the neutering calms these behaviours”. (9 months) “Since her first proper season she has calmed a lot and is behaving so much better.” (12 months) |

| d. Age | “[Dog’s name] likes to bite and nip and lunge at your face when biting. I have been told this is normal puppy behaviour especially when teething. (…) [Dog’s name] is acting like a typical toddler”. (12–16 weeks) “Best way I can describe this is that he’s being sassy! Just normal ‘teenager’ behaviour as far as I am aware. Not following basic commands he definitely knows likes sit—recall has worsened—tearing up his bed—humping”. (6 months) “We are training lightly, but although he is a big dog, he is immature so we only do short spells of training.” (12 months) “Much more mature in last 6 weeks, no more digging in garden, rolling on dead things, eating nasty items, also much less worried about unfamiliar looking people”. (18 months) |

| 2. Dog’s personality/deliberate action | |

| “She’s definitely learnt what’s acceptable and what’s not although she’ll sometimes do it anyway but clearly knows she shouldn’t.” (12–16 weeks) “She had started in the last few weeks pushing the boundaries and ‘barking’ back when I tell her no or go to move her.” (6 months) “Pulls on lead despite loose lead walk training. Doesn’t ask to go out to toilet, relies on us to open door, and will have ‘accidents’”. (12 months) “He is very independent and will ignore recall completely most of the time”. (18 months) | |

| 3. External influence | |

| a. Training and socialisation | “We are desperately trying to stop the behaviour and when we say ‘off’ he does stop and we treat him. However he has now learnt if he bites and told to ‘off’ he gets a treat. Tricky—work in progress. Been told he’ll grow out of by a dog trainer.” (12–16 weeks) “After just a few weeks [of training/socialisation classes], I have noticed a big change in [dog’s name] attitude and confidence both in class and when out during walks.” (6 months) “Considering her breed specifics I’m really pleased with how [Dog’s name] is doing, I have worked hard at socialising her & teaching her tricks & games”. (9- months) “Her training is paying off and she is a lovely and generally well behaved dog (…)”. (18 months). |

| b. Influenced by people | “[M]ost of the time people encourage it by stroking him which annoys me and that’s why he keeps thinking its ok. At home I discourage it and he’s starting to listen but on walks strangers re-enforce it.” (12–16 weeks) “[Dog’s name] is shy and timid with other people. This goes back to 2 incidents which happened during his fear period at about 8—10 weeks, when he was picked up from the floor without warning (…). It happened so quickly that I couldn’t stop it and [dog’s name] really took offense.” (6 months) “When he doesn’t want to head back home after a walk he will grumble and try and nibble your feet. (He mainly does this to my husband as he is a soft touch)”. (2 years) |

| c. Influenced by other dogs | “Copying the poor behaviour in my other dogs—jumping up at the front gate when the postman comes”. (12–16 weeks) “Not sure if it’s because we have an older dog to help, but having [Dog’s name] has been far easier than our last puppy experience, she’s keen to learn and for a pup behaves very well”. (6 months) “[Dog’s name] is a confident dog—maybe because he has had the older dog as a role model and company.” (18 months) |

| Code | 12–16 Weeks | 6 and 9 Months | 12 and 18 Months | 2 Years | Change Over Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship with a dog | |||||

| a. Dog’s love and bond with a dog | “He is a lovely funny boy, and gives me hours of happiness” | “He has been and is a godsend. Would be totally lost without him even after only 4-5 months with us. He has given me a purpose and focus to each day.” (6 months) | “He is a lovely dog. Such a great nature and great with the children. He is very soppy!” (18 months) | “She fits into our family and helps us get out and about with the kids. Even on days we don’t want to leave the house! She has grown into such an important part of our family and has taught the children a lot in the short space of time we have had her. She is a wonderful dog and we all love her loads!” | No change |

| b. Entertainment and fun | “He’s a funny, little fellow, who makes me laugh” | “Makes us laugh too” (6 months) | “He keeps us amused and entertained” (12 months) | “There are certain things about dogs that make you laugh and she is hilarious (…) she loves stones to be thrown for her she goes mental and spins around!” | No change |

| 2. Dog’s personality/disposition | |||||

| a. Happiness | “Very happy contented puppy” | “[Dog’s name]” is a very happy” (6 months) | “[Dog’s name] continues to be a happy friendly dog.” (12 months) | “(…) she grunts in pleasure when she is stroked (…) she literally jumps for joy on the beach, dancing with happiness” | No change |

| b. Enthusiasm | “He’s very (…) enthusiastic towards everyone and other dogs” | “She loves everything and has enthusiasm for life.” (9- months) | “She charges around like a ballistic missile much of time and is mega- enthusiastic about life.” (12 months) | “She (...) has an amazing zest for life. She does everything with such enthusiasm and joy” | No change |

| c. Mischief and sassiness | “Sleeping less, more mischievous” | “A very happy puppy who is playful loving brave and sassy, a little naughty but a joy to own” (6 months) | “[Dog’s name] is a playful, cheeky pickle.” (12- months) | “Her eyebrows raise when I ask her to do something and she can be very clever/sneaky in trying to get up to mischief!” | Dogs described as mischievous at all timepoints; more common in the 6- and 9-month surveys. |

| d. Unique character | “Pushes new boundaries each day. Has character” | “We want a dog with real character and that means sometimes mischievous.” (6 months) | “[Dog’s name] is a real character and a joy to share the house with.” (18 months) | “He still pinches my pants and runs round the garden with them!—he is such a Scamp and just great fun—a real character” | Dog’s unique characteristic discussed at all timepoints. From 6 months onwards, comments about dogs ‘becoming’ or ‘growing into’ themselves and their unique character are more noticeable. |

| e. Affection | “Very kissy. Loves cuddles”. | “She (…) loves nothing more than a cuddle”. (9 months) | “[Dog’s name] has developed into a lovely affectionate dog” (12- months) | “The cuddles we have in the morning, before we start our day. It is a lovely calm moment in our day and a great beginning” | Dogs described as affectionate at all timepoints; more common in the 18-month and 2-year surveys. |

| f. Calmness and ability to relax | “[Dog’s name] is the calmest puppy I have ever known.” | “I appear to have been lucky in that she seems to have a very loving laid back personality where little bothers her” (6 months) | “[Dog’s name] has calmed down a lot since a puppy.” (12 months) | “He is calm, relaxed and an angel around the home.” | In the 12–16-week and 6-month surveys, dog’s calm/relaxed behaviour was seen as an exception. Owners commented on their dogs becoming calmer, more settled and more relaxed from 12 months onwards. |

| g. Curiosity | “[dog’s name] is a (…), friendly and inquisitive puppy.” | “[Dog’s name] appears to be an alert, inquisitive and intelligent pup” (6 months) | “He is very bright and curious and good natured” (18 months | “He is a very curious dog who always likes to check out everything new in his environment, sniffing around at everything.” | No change |

| h. Confidence | “Although [dog’s name] was very quiet when we first picked her up, she certainly has grown in confidence and has a huge fun character” | “She loves her older two sisters and is confident and happy.” (9 months) | “Very active and confident” (18 months) | “He is also a brave dog who might be a little tentative about something at first, but then will always end up achieving whatever it is he wants.” | Comments on dog’s growth in confidence were common in the 12–16-week survey and continued until 18 months. Concerns regarding dog’s lack of confidence were raised in all but 6-month surveys. In the 12- and 18-month surveys, many owners stated that dog’s confidence is improving. |

| 3. Training | |||||

| a. Training progress | “His toilet training is amazing I’m so proud of him and how fast he is learning.” | “He is learning to be walked off lead and his recall is incredible! Very proud puppy parent!” (6 months) | “[Dog’s name] is very easy to train and learn new tricks” (18 months) | “A delightful dog with a lot of charm, easy to work with, tries to please” | In 12–16-month surveys, comments on how quickly dog learns and the dog’s progress were common. Owners also noticed improvement in dog’s trainability from 12 months onwards. |

| b. Ability to fit with the family | “She is travelling in the car well (…) and she is growing in confidence in new social situations, including going into shops, cafes and pubs. Fab!” | “He’s great (…) meeting new people, not fussed about being left on his own, has slept in lots of different houses and doesn’t seem phased, and has generally adjusted to life with us fantastically” (6 months) | “She has coped well with family changes/absences and the disruptions this caused to her routines.” (18 months) | “She adapts well to new situations, I feel like I can take her anywhere!” | In all surveys, owners noticed how quickly their dog adapted to the family (early surveys) or to changes within family (later surveys). |

| 4. Physical appearance and healthy development | |||||

| “[Dog’s name] is a wonderful border collie puppy, who is developing beautifully.” | “[Dog’s name] in developing into a big, beautiful, healthy dog” (6 months) | “He is a strong, muscular ‘tigger’” (18 months) | “She has very expressive facial expressions, and makes me laugh all the time.” | Owners commented on dog’s cuteness and growth more often in the 12–16-week surveys. | |

| Code | 12–16 Weeks | 6 and 9 Months | 12 and 18 Months | 2 Years | Change over Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Settling into home and family life | |||||

| a. Ability to settle and adapt | “We are finding it hard during the night. He sometimes wakes at 1–2 am for a wee. (…). We take it in turns to get up early and then that person has an afternoon nap! We just don’t know how to get over this. (…)” | “Sometimes he will not stay in his bed at night and barks until we get up and let him into our room. He won’t settle unless he is with us. I would say this is 2–3 nights a week for the past month.” (6 months) | “Difficulty settling in different places, including on long car journeys (fine on short trips).” (12 months) | “He doesn’t like things to change, and gets very upset if things move place or aren’t in the right routine.” | More common in the 12–16-week survey than later. In the early survey, issues with settling in were more often related to dog settling in at night. Later, issues with settling in included dog struggling to adapt to change in their routine. |

| b. Difficult to leave alone | “Difficult to leave alone. Follows me and needs to be near someone all the time.” | “He is also extremely bonded to me (…) This causes issues if we’re out and I pop into a shop or go out of sight. He will become anxious and tremble.” (6 months) | “I am unable to leave him at all. He barks and whines when on his own.” (12 months) | “Doesn’t like to be on her own.” | No change |

| c. Destroys things | “Picking up stones of all sizes and chewing them, sometimes swallowing them. Chewing plastic and paper and swallowing some of it.” | “(…) he stills chews shoes, socks and anything loose, but this is becoming less so sure he will stop at some point!” (6 months) | “(…) He still steals and destroys odd items if they are left out: yellow washing-up cloths, letters and magazines, plastic bags—we have learnt to be very tidy!” (18 months) | “He eats socks. Then forgets he’s hiding it in his mouth, then I have to go poopascoop socks from the garden!” | Dog chewing inappropriate items and being destructive was discussed more often in the 12–16-week survey, when the behaviour was seen as expected due to young age or teething. From 6 months onwards, destructive behaviour was discussed as something that a dog was ‘still’ doing. |

| 2. Issues with training | |||||

| a. Housetraining | “We are finding house training a challenge. [Dog’s name] seems to pee a lot, we take him outside upwards of 15 times a day but still have accidents.” | “[S]eems to have gone a bit backwards with toilet training. He had stopped peeing/pooping in the house but now the weather has gotten bad he has started again.” (9 months) | “Will also occasionally wee indoors just after a walk outside. Also toilets indoors when staying with friend.” (12 months) | “He’s still weeing up things in the house!” | Housetraining issues were discussed at all timepoints, albeit more frequently in the 12–16-week survey. |

| b. Ignoring commands/testing boundaries | “Pushes new boundaries each day.” | “Recall has regressed, after lots of intensive training it seems he is challenging things and testing boundaries. Had to take training back to basics at times recently as interest to meet other dogs is greater than his desire to listen to the basic commands he knows and used to perform flawlessly a month or two ago.” (6 months) | “She does not come when called—often ignores me.” (18 months) | “How sassy she can be when she argues back if she starts barking and you tell her to be quiet she will bark back as if to be like no don’t tell me what to do.” | Ignoring known commands, ‘pushing boundaries’ and, in particular, deterioration of dog’s recall was very common in comments in the 6-, 9- and 12-month surveys. |

| 3. Challenging personality/dispositions | |||||

| a. Stubborn | “He is very strongly self- willed.” | “[Dog’s name] is (…) very stubborn and is taking more training than we have had with other breeds.” (9 months) | “He is stubborn and I don’t think we’ll ever really get him not to pull on the lead.” (18 months) | “She can be very wilful. She will only do something because she wants to.” | No change |

| b. Too excitable/boisterous | “He’s very excitable (…) Jumping up at people whenever he sees them.” | “[Dog’s name] has started being very hyperactive and overexcited towards other dogs/people pulling and lunging at them on the walks with the intention of playing.” (6 months) | “gets wayyyyyy overexcited and overstimulated and finds it hard to focus on training or what he’s being asked.” (12 months) | “He still gets over aroused easily, especially around other dogs. He thinks they all want to play and his play is typical Doodle- very excited.” | Discussed at all timepoints. In 6-month and later surveys, owners more often discussed this as ‘still’ being an issue, whereas in the 12–16-week survey, it was something that was expected. |

| c. Lack of confidence/nervousness | “She is a little nervous at new situations and around other puppies at times.” | “We are a bit upset at how submissive she is. She seems to have little confidence. She is to be a gun dog and already my husband tells me to rehome her as she is too soft.” (6 months) | “Shyness with people she doesn’t know- more when she is indoors than outside.” (18 months) | “She is a more nervous dog than I would have hoped.” | Nervousness and lack of confidence were mentioned most often in the 12–16-week survey. |

| d. Attention seeking/jealous | “Barking at people, dogs and for attention.(…) shows signs of jealousy with our other dog.” | “Her jealousy of all attention that I give to (..) her sister. [Dog’s name] wants all attention from me focused on her only.” (6 months) | “Attention seeking barking.” (18 months) | “He’s pretty wimpy and needy! (…) He is very green eyed and doesn’t really like our other dogs being fussed, he tries to push his way in.” | No change |

| 4. Challenging behaviour | |||||

| a. Chasing animals | - | “He ignores me on walks and has chased sheep when his longline snapped.” (9 months) | “Tends to chase livestock/deer if off lead so has to be kept on lead” much of the time in nearby deer park.” (12 months) | “She is a chaser and disappears in a flash when she catches an interesting smell. Chases birds, deer and twice she has chased sheep.” | Not mentioned in the 12–16-week survey. Comments about chasing other animals most common in the 18-month survey. |

| b. Issues aroura other dogs | “Mildly reactive (alarm barking, backing away) toward strange dogs when encountered unexpectedly.” | “He snarls and barks [at other dogs], but is wagging his tail at the same time. Sometimes he will turn on my other dog as an outlet for his excitement. They sound as if they are having a serious fight, but don’t seem to hurt one another” (9 months) | “She sometimes plays with them [other dogs], but soon gets bored of them and she can be quite grumpy and growls & snaps at them when she’s had enough.” (18 months) | “He can be reactive to some other males.” | Comments regarding dog’s reactivity and aggression towards other dogs were more common from 12 months onward. At 2 years, a number of owners stated that this behaviour was improving. |

| c. Behaviour around people | “Barking, snarling and snapping (usually when we eat).” | “[Dog’s name] can react (barking, pulling away) from some people we meet.” (6 months) | “Won’t allow strangers to touch him, not generally a problem but could be in the future.” (18 months) | “Her terrier tendency to sometimes be snappy and grumpy.” | Issues around known and unfamiliar people were not common; listed more often 6 months onwards. |

| d. Pulling on lead | “Pulls on lead but working on her.” | “Pulling on the lead, which he never used to do.” (6 months) | “He is pulling on the lead constantly so I have to keep re training him which is annoying.” (12 months) | “He still pulls on the lead.” | Discussed in all surveys. Many owners thought that the behaviour was worse than previously in the 6- and 9-month surveys. |

| e. Barking | “Very vocal when playing with other dogs (…).” | “He has just started to bark at people going past, at shadows and a lot of other things which is annoying and we hope he will get less barky as he learns what is to bark at and what isn’t’.” (9 months) | “Barking for nothing and when we get home.” (12 months) | “Prolonged loud barking at any noise at all.” | Barking was discussed more often from 6 months onwards. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Harvey, N.D.; Giragosian, K.; Kinsman, R.H.; Casey, R.A.; Tasker, S.; Murray, J.K. “It’s Like Living with a Sassy Teenager!”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Owners’ Comments about Dogs between the Ages of 12 Weeks and 2 Years. Animals 2023, 13, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13111863

Owczarczak-Garstecka SC, Da Costa REP, Harvey ND, Giragosian K, Kinsman RH, Casey RA, Tasker S, Murray JK. “It’s Like Living with a Sassy Teenager!”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Owners’ Comments about Dogs between the Ages of 12 Weeks and 2 Years. Animals. 2023; 13(11):1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13111863

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwczarczak-Garstecka, Sara C., Rosa E. P. Da Costa, Naomi D. Harvey, Kassandra Giragosian, Rachel H. Kinsman, Rachel A. Casey, Séverine Tasker, and Jane K. Murray. 2023. "“It’s Like Living with a Sassy Teenager!”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Owners’ Comments about Dogs between the Ages of 12 Weeks and 2 Years" Animals 13, no. 11: 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13111863

APA StyleOwczarczak-Garstecka, S. C., Da Costa, R. E. P., Harvey, N. D., Giragosian, K., Kinsman, R. H., Casey, R. A., Tasker, S., & Murray, J. K. (2023). “It’s Like Living with a Sassy Teenager!”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Owners’ Comments about Dogs between the Ages of 12 Weeks and 2 Years. Animals, 13(11), 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13111863