Sign Language Studies with Chimpanzees in Sanctuary

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Chimpanzee Biographical Information

2.2. Sign Language Records

2.2.1. Sign Criteria

2.2.2. Sign Checklists and Logs

2.2.3. Observer Caregivers

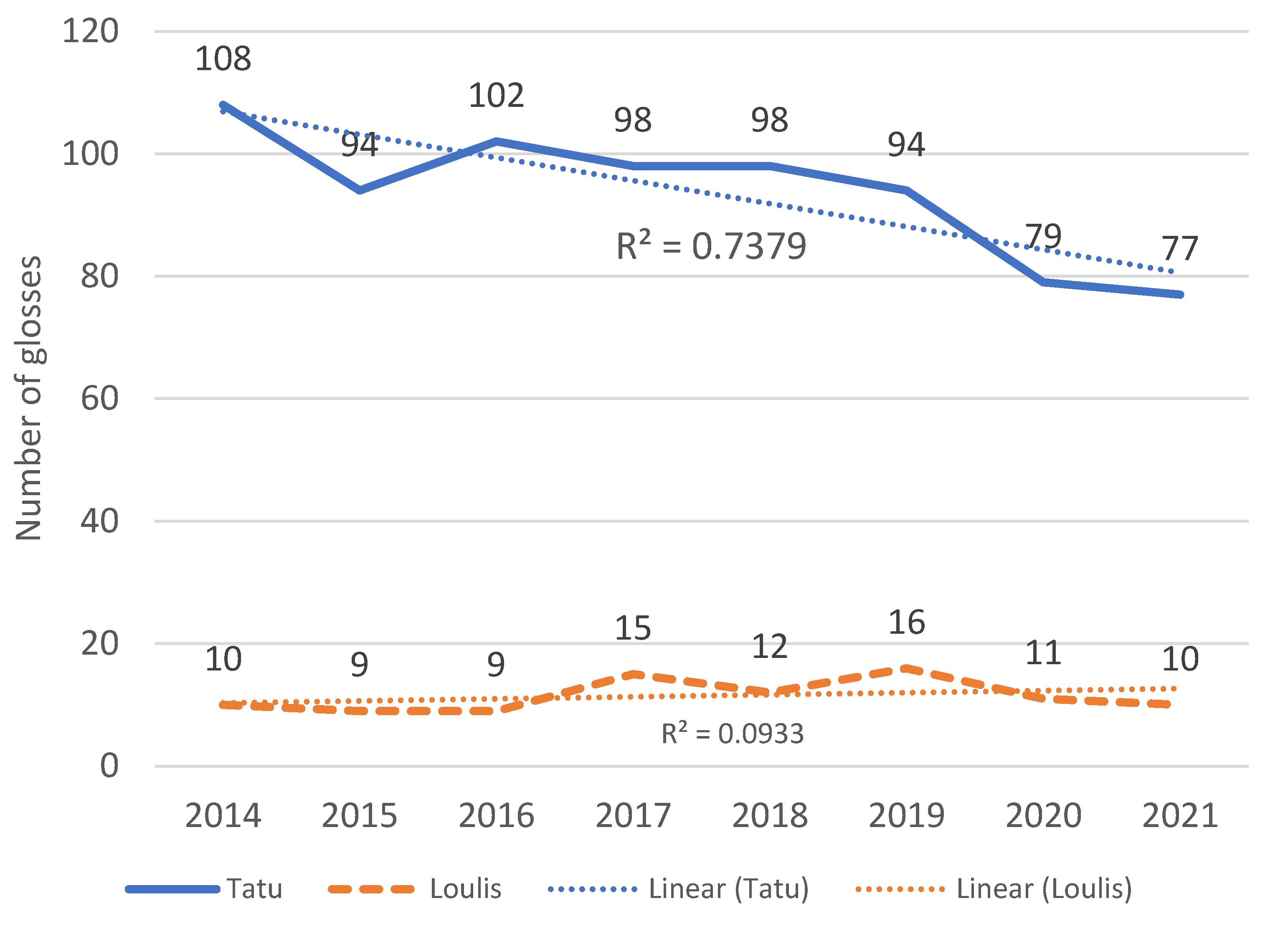

3. Study 1. Vocabulary Production and Maintenance

3.1. Method

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

3.3.1. Signs in Context

1 February 2018 When I returned to the chimp house following lunch, Tatu was sitting on the stairs above Room 4. I stopped in the kitchen to say hello, she signed DRINK. I glanced around but nothing stood out as truly appealing for her. I asked WHAT DRINK? She replied WATER. I followed her upstairs, where she signed THAT pointing towards the hose. I looked at the hose, and she signed WATER.

30 December 2013 Today is Tatu’s birthday. When I came in this morning I told her HELLO! TODAY TATU DAY! Tatu pant-hooted while signing DRINK MILK.

4 November 2018 I was in the kitchen and I heard a clapping sound. I turned to look at Tatu and she signed PERSON. I verbally replied “yes”? She said THAT MEDICINE pointing to the Vitamin C bottle so I said “Oh yeah sure!” and gave her 2 Vitamin C.

10 January 2014 The first day that [the medical staff] went in with Yoko they sent the rest of us out of the building. When we returned, everyone was out of Yoko’s room and Tatu very excitedly signed to me PERSON IN THERE ([the sign] there gestured to the room Yoko was in). I make [a] surprised face [and ask Tatu] IN THERE? Tatu signed PERSON THERE.

4 October 2013 Binky was quadrupedal running down the long tunnel while Loulis was running parallel alongside the upstairs mezzanine windows. Binky was quadrupedal running in the tunnel, Loulis stopped at a window and signed CHASE. This is the first time I’ve seen him sign to anyone new except Sue and he mostly signs HURRY to her.

18 August 2017 Walking into the entrance this morning Lou was at Sue’s tunnel when he saw me and started signing CHASE repeatedly. I was plugging in the combination to the entrance when he started signing HURRY. We played chase for several minutes, inside and outside of the Mezzanine. When we stopped, I was by the laundry and my coffee mug was in sight. Loulis signed DRINK but I didn’t know what drink yet, and I asked WHAT DRINK? He signed THAT towards my coffee mug.

HURRY also was one of Loulis’s higher-ranked signs.

10 July 2017 I was cleaning Room 1 in the morning when Loulis approached the door to the Mezzanine that faces Room 1 downstairs. Loulis bronx cheered to get my attention. I turned and met his gaze, he signed THAT at me. I responded WHAT DO NOW? He signed DRINK so I gave him a drink from the hose. As I prepped the hose Loulis signed HURRY.

3.3.2. Environmental Constraints

3.3.3. Indexical Signs

7 January 2014 Tatu sits up on scale downstairs in Jeannie’s area. She looks toward the kitchen and signs DRINK. I look around and do not see a drink. [I ask] WHERE? Tatu signs DRINK THERE. [I reply] I DO NOT UNDERSTAND. Tatu signs STUPID [I ask] WHAT YOU WANT? Tatu signs THAT, to kitchen… I still don’t know what drink she was signing about but I gave her a vitamin C tablet and she seemed happy.

3.3.4. Memory

16 January 2018 Tatu clapped to get my attention this morning and when I looked over she signed DAR. I replied, with a very confused look, DAR? She repeated DAR, but didn’t elaborate. Maybe she dreamt about her old friend.

4. Study 2. Communicative Function

4.1. Method

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Categories of Communicative Function

20 November 2013 Tatu ate her multivitamin and soymilk cup. She asked for MILK. I replied MILK FINISHED. YOU WANT FRUIT? Tatu signed FRUIT. I signed APPLE BANANA PEACH WHICH? Tatu signed PEAR.

- In this example, the first response is the subcategory Yes-No Answer and the second is Wh-Answer. Other answers to questions were about the environment as in the following interaction about a maintenance man, M, whom Tatu knew.

6 February 2014 Tatu was sitting on the ground in Jeannie’s area. I sat down next to her and asked M if he wanted to sit with us. I asked Tatu WHO THAT? Tatu signed FRIEND. I signed BOY GIRL WHICH? Tatu signed BOY. I signed YOU FUNNY!

- In the above example, the responses are in the Wh-Answer subcategory. The chimpanzees used all of the subcategories in the Response category reflecting the variety of question types from caregivers and the variety of ways to answer.

10 November 2013 Loulis sits up on ground in upstairs apartment. Binky and Maya [were] in Back 1. They’re sitting near the caging. Loulis signed HURRY towards Binky and Maya. Binky did not respond. Maya did not respond.

- Loulis’s attempts to initiate an interaction with the sign HURRY fail. The following interaction is an example of the subcategory Accompaniment:

12 February 2014 Loulis is clinging on the cage in Room 1, [Caregiver T] is getting the [dinner] trolleys ready with tonight’s vegetables. Loulis begins to breathy-pant and orients himself at Spock. Loulis signs HURRY to Spock while climbing on the caging toward Spock. Spock is sitting up on the bench in Room 1 looking towards Loulis. They both breathy-pant and Loulis approaches Spock. They embrace, hug and open mouth kiss each other. After, Loulis climbs down onto the ground and Spock breathy-pants and looks toward the kitchen.

- Breathy pants are an indicator of the excitement of the anticipation of a meal. The sign HURRY accompanies the general shared excitement.

7 October 2013 I gave [Tatu and Loulis] each a tofu dog around 2 pm today. A few minutes later, Tatu was lying in the hammock outside and asked MORE MEAT. I signed YES! Wait there…” I went to get another tofu dog (plain, by the way—no bun or mustard or anything).

- Requests also could serve as requests for action. For example:

26 October 2013 Tatu goes into apartment. Spock enters [an adjacent room] Back 1. Tatu approaches and bounces towards Spock. Spock sits. Tatu sits beside Spock. Tatu signs GROOM looking toward Spock.

26 December 2013 Toby [another chimpanzee] and Loulis had been displaying on opposite sides of the upstairs (Lou on Mezzanine side, Toby on Jean’s side). Toby started by raking a metal bowl on the floor. Lou did the same. Toby banged on the door separating them. Loulis clung to the cage on the Mezzanine side. When Toby took a few steps back, Loulis banged on the door. Rachel [another chimpanzee in Toby’s enclosure] came over and hit the door a few times. Loulis climbed higher on the caging and signed HURRY to Toby. Toby came over and sat down in front of Rachel.

18 February 2014 I brought Tatu a drink and told her QUIET SODAPOP IN THERE (it was Nestea Zero). Tatu takes a few sips. I verbally ask Spock “Do you want some of this drink?” Tatu looks at Spock and signs SODAPOP.

4 February 2014 Tatu was sitting up on the bench upstairs Mezzanine. Tatu signed LOTION THERE. I gave her some lotion. Tatu signed IN. I asked IN WHERE? Tatu signed THERE (towards Room 1). I signed IN SOON KEY GIRL THERE CLEAN (Caregiver K). Tatu signed KEY. I signed YES THAT KEY GIRL. Tatu signed HURRY KEY

11 November 2013 Tatu was sitting beside Jeannie’s door upstairs in the Mezzanine. Tatu signed PEACH. I signed “Sorry can’t. You hungry?” Tatu signed HUNGRY. I signed “Want vegetable?” Tatu signed VEGETABLE. I brought her (and Chance [another chimpanzee] who was sitting nearby) a cucumber.

- Internal reports also refer to sentiments. SORRY was in several of the interactions in this study. For example:

18 October 2013 The day after they first met, Tatu and Spock were playing tickle and wrestle in Jeannie’s front Room 1. Chance [another chimpanzee in an adjacent enclosure] came into Room 5 and began screaming. Tatu sat up, startled. She looked at Chance and signed SORRY.

- This interaction was coded with two codes. The sign SORRY was both a Statement: Internal Report and a Conversational Device: Politeness Marker.

4.2.2. Interaction Partner

4.3. Discussion

4.3.1. Partner and Communicative Function

4.3.2. Uninterpretable Utterances

4.3.3. Private Signs

26 July 2014 I was sitting looking for Tatu in the upstairs mezzanine when I poked my head out of the window and saw her in the beginning of Lou’s tunnel. She was sitting there all alone and she signed COFFEE. She must have thought it was a good time for coffee. She didn’t notice me at the window either.

13 May 2014 Tatu sat up in Lou’s tunnel and held up a mirror with her left hand. She looked at her reflection and signed EARRING 3 separate times.

28 January 2014 Tatu was lying down on a pile of blankets while I groomed her side. She signed Tatu CARROT LOTION. [Then again] Tatu CARROT LOTION CARROT. It looked like she was just ‘rhyming’.

4.3.4. Sign Modulation

25 December 2013 Loulis was sitting in the Room 1/Apartment tunnel area (in Sue Ellen’s bed). [Caregiver G] had just handed out Christmas gift bags and everyone was really excited. Loulis was breathy panting and also fear grimacing. Spock was sitting on the upstairs platform of Back 1. Spock laid down on the platform with his face oriented towards Loulis. They breathy panted [oriented toward] each other for a few minutes, and then Loulis signed HURRY [with both hands] to Spock. They continued breathy panting at each other.

5. General Discussion

5.1. Signs in Sanctuary

5.2. Individual Differences and Generalizability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardner, R.A.; Gardner, B.T. Teaching sign language to a chimpanzee. Science 1969, 165, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.A.; Gardner, B.T. Comparative psychology and language acquisition. Annals New York Acad. Sci. 1978, 309, 37–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouts, R.S. Transmission of a human gestural language in a chimpanzee mother-infant relationship. In The Ethological Roots of Culture; Gardner, R.A., Gardner, B.T., Chiarelli, B., Plooij, F.X., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fouts, D.H. The use of remote video recordings to study the use of American Sign Language by chimpanzees when no humans are present. In The Ethological Roots of Culture; Gardner, R.A., Gardner, B.T., Chiarelli, B., Plooij, F.X., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bodamer, M.D.; Gardner, R.A. How cross-fostered chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) initiate and maintain conversations. J. Comp. Psychol. 2002, 116, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, C.A.; Jensvold, M.L. The communicative function of five signing chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Pragmat. Cogn. 2013, 21, 224–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.A.; Beran, M.J. Words matter: Reflections on language projects with chimpanzees and their implications. Am. J. Primatol. 2020, 82, e23187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, W.N. Communication and language in the home-raised chimpanzees. Science 1968, 162, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.J.; Nissen, C.H. Higher mental functions of a home-raised chimpanzee. In Behavior of Nonhuman Primates; Schrier, A.M., Stollnitz, F., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971; Volume 4, pp. 59–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R.A.; Gardner, B.T. Early signs of language in child and chimpanzee. Science 1975, 187, 752–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.A.; Gardner, B.T. A vocabulary test for chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J. Comp. Psychol. 1984, 98, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.T.; Gardner, R.A. Evidence for sentence constituents in the early utterances of child and chimpanzee. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1975, 104, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.T.; Gardner, R.A. Development of phrases in the utterances of children and cross-fostered chimpanzees. In The Ethological Roots of Culture; Gardner, R.A., Gardner, B.T., Chiarelli, B., Plooij, F.X., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 223–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, B.T.; Gardner, R.A. Signs of intelligence in cross-fostered chimpanzees. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 1985, 308, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rimpau, J.B.; Gardner, R.A.; Gardner, B.T. Expression of person, place, and instrument in ASL utterances of children and chimpanzees. In Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees; Gardner, R.A., Gardner, B.T., Van Cantfort, T.E., Eds.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 240–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chalcraft, V.J.; Gardner, R.A. Cross-fostered chimpanzees modulate signs of American Sign Language. Gesture 2005, 5, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensvold, M.L. Conversations with Chimpanzees: What They’ve Told Me. In The Chimpanzee Chronicles; Rosen, D., Ed.; Wild Soul Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2020; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hobaiter, C.; Byrne, R.W. The gestural repertoire of the wild chimpanzee. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobaiter, C.; Byrne, R.W. The meanings of chimpanzee gestures. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensvold, M.L.; Dombrausky, K. Sign language in chimpanzees across environments. In Chimpanzee Behavior: Recent Understandings from Captivity and the Forest; Jensvold, M.L., Ed.; Nova Science Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- Fouts, R.S.; Jensvold, M.L.A.; Fouts, D.H. Chimpanzee signing: Darwinian realities and Cartesian delusions. In The Cognitive Animal: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives in Animal Cognition; Bekoff, M., Allen, C., Burghardt, G., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fouts, R.S.; Fouts, D.H.; Van Cantfort, T.E. The infant Loulis learns signs from cross-fostered chimpanzees. In Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees; Gardner, R., Gardner, B., Van Cantfort, T., Eds.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 280–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fouts, R.S.; Hirsch, A.D.; Fouts, D.H. Cultural transmission of a human language in a chimpanzee mother-infant relationship. In Child Nurturance: Studies of Development in Nonhuman Primates; Fitzgerald, H.E., Mullins, J.A., Gage, P., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 3, pp. 159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Jensvold, M.L.A.; Gardner, R.A. Interactive use of sign language by cross-fostered chimpanzees. J. Comp. Psychol. 2000, 114, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitten, L.; Jensvold, M.L.; Fouts, R.S.; Wallin, J.M. Contingency in requests of signing chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Interact. Stud. 2012, 13, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.Q. Timing of turn initiations in signed conversations with cross-fostered chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2011, 24, 177–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.T.; Gardner, R.A.; Nichols, S.G. The shapes and uses of signs in a cross-fostering laboratory. In Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees; Gardner, R., Gardner, B., Van Cantfort, T., Eds.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 55–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, W.C.; Casterline, D.C.; Croneberg, C.G. A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles; Gallaudet College Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrausky, K.; Hings, C.; Jensvold, M.L.; Shaw, H. Variability in Sign Use in Chimpanzees Before and After Relocation; Poster Presented at Rocky Mountain Psychological Association: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Valli, C.; Lucas, C. Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Gallaudet University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Klima, E.S.; Bellugi, U. The Signs of Language; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beran, M.J.; Heimbauer, L.A. A longitudinal assessment of vocabulary retention in symbol-competent chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, M.J.; Pate, J.L.; Richardson, W.K.; Rumbaugh, D.M. A chimpanzee’s (Pan troglodytes) long-term retention of lexigrams. Anim. Learn. Behav. 2000, 28, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodamer, M. Key out: A Chimpanzee’s petition for freedom. In The Chimpanzee Chronicles; Rosenman, D., Ed.; Wild Soul: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2020; pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zoo Family Mourns Passing of Chantek. Available online: https://zooatlanta.org/zoo-family-mourns-passing-chantek/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Dore, J. Holophrases, speech acts and language universals. J. Child Lang. 1975, 2, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, J. Children’s illocutionary acts. In Discourse Production and Comprehension; Freedle, R.O., Ed.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1, pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Dore, J. “Oh them sheriff”: A pragmatic analysis of children’s responses to questions. In Child Discourse; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- MacRoy-Higgins, M.; Kaufman, I. Pragmatic functions of toddlers who are late talkers. Commun. Disord. Q. 2012, 33, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRoy-Higgins, M.; Kliment, S. Pragmatic functions in late talkers: A 1-year follow-up study. Commun. Disord. Q. 2017, 38, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.O.; Albakri, I.S.M.A.; Seng, G.H. Pragmatic competence and activity-based language teaching: Importance of teaching communicative functions in Iraq EFL context. Int. J. Engl. Lit. Soc. Sci. (IJELS) 2019, 4, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, P.S. Deaf children’s expression of communicative intentions. J. Commun. Disord. 1986, 19, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ervin-Tripp, S. “Wait for me, roller skate!”. In Child Discourse; Ervin-Tripp, S., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby, A.M.; Rodriguez, G.P. Measurement of communicative intentions in normally developing children during structured and unstructured contexts. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1992, 35, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, E. Recent use of signs by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in interactions with humans. J. Comp. Psychol. 2005, 119, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Dolz, J.; Riba, D.; Crailsheim, D. Neighbors matter: An investigation into intergroup interactions affecting the social networks of adjacent chimpanzee groups. Ecologies 2023, 4, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videan, E.N.; Fritz, J.; Schwandt, M.; Howell, S. Neighbor effect: Evidence of affiliative and agonistic social contagion in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Primatol. 2005, 66, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.C.; Aureli, F. The neighbor effect: Other groups influence intragroup agonistic behavior in captive chimpanzees. Am. J. Primatol. 1996, 40, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodamer, M.D.; Fouts, R.S.; Fouts, D.H.; Jensvold, M.L.A. Private signing in chimpanzees. Hum. Evol. 1994, 9, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensvold, M.L.; Fouts, R.S. Imaginary play in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Hum. Evol. 1993, 8, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Shenk, C. A microanalysis of the nonmanual components of questions in American Sign Language. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nespor, M.; Sandler, W. Prosody in Israeli sign language. Lang. Speech 1999, 42, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, J. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Covington, V.C. Juncture in American Sign Language. Sign Lang. Stud. 1973, 2, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cianelli, S.N.; Fouts, R.S. Chimpanzee to chimpanzee American Sign Language: Communication during high arousal interactions. Human Evol. 1998, 13, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumm, P.; Gardner, B.T.; Gardner, R.A. Vocal and gestural responses of cross-fostered chimpanzees. Am. J. Psychol. 1986, 99, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, H.L.; Scheel, M.H.; Gardner, R.A. Tomasello turns back the clock. American J. Psychol. 2017, 130, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. Beyond WEIRD: Towards a broad-based behavioral science. Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielson, M.; Haun, D.; Kärtner, J.; Legare, C.H. The persistent sampling bias in developmental psychology: A call to action. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2017, 162, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavens, D.A.; Bard, K.A.; Hopkins, W.D. The mismeasure of ape social cognition. Anim. Cogn. 2019, 22, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, T.P.; Leavens, D.A.; Susswein, N.; Wereha, T.J. Conceptual and methodological issues in the investigation of primate intersubjectivity. In Enacting Intersubjectivity: A Cognitive and Social Perspective on the Study of Interactions; Morganti, F., Carassa, A., Riva, G., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Newport, E.L.; Bavelier, D.; Neville, H.J. Critical thinking about critical periods: Perspectives on a critical period for language acquisition. In Language, Brain and Cognitive Development: Essays in Honor of Jacques Mehler; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 481–502. [Google Scholar]

| Tatu | Loulis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Checklists | Range | M (%) | Total Tokens | Number of Checklists | Range | M (%) | Total Tokens | |

| 2014 | 283 | 1–58 | 15.60 (7) | 4401 | 254 | 1–10 | 3.96 (5) | 1005 |

| 2015 | 257 | 1–33 | 12.48 (6) | 3208 | 189 | 1–9 | 3.84 (4) | 736 |

| 2016 | 238 | 1–32 | 14.47 (7) | 3446 | 181 | 1–12 | 4.11 (5) | 744 |

| 2017 | 270 | 1–46 | 14.19 (6) | 3832 | 234 | 1–12 | 4.39 (5) | 1033 |

| 2018 | 303 | 1–32 | 12.06 (6) | 3666 | 343 | 1–12 | 3.73 (4) | 1279 |

| 2019 | 312 | 1–26 | 11.88 (6) | 3707 | 260 | 1–8 | 3.61 (5) | 938 |

| 2020 | 273 | 1–24 | 10.79 (5) | 2923 | 237 | 1–9 | 3.93 (5) | 928 |

| 2021 | 252 | 2–21 | 10.51 (5) | 2650 | 247 | 1–13 | 4.02 (5) | 949 |

| DRINK | 1746 | GRASS | 201 | GIRL | 32 | VEGETABLE | 3 |

| THAT | 1531 | MEDICINE | 195 | CANDY | 31 | GLASS | 2 |

| PERSON | 1509 | SODAPOP | 189 | SWALLOW | 30 | MARY LEE J | 2 |

| THERE | 1422 | FOOD/EAT | 171 | UP | 25 | METAL | 2 |

| YOU | 1307 | CORN | 145 | BOY | 22 | SHIT | 2 |

| MILK | 1298 | TEA | 137 | OUT | 21 | TIME | 2 |

| GO | 1213 | FRUIT | 131 | POTTY | 20 | WRISTWATCH | 2 |

| HURRY | 1065 | POTATO | 123 | COW | 19 | BAG | 1 |

| IN/ENTER | 954 | TATU | 116 | PEA/BEAN | 19 | COLOR | 1 |

| CRACKER | 920 | BIRD | 112 | CAT | 18 | DEBBI F. | 1 |

| BANANA | 871 | FLOWER | 112 | TICKLE | 18 | DIAPER | 1 |

| SMELL | 859 | BREAD | 98 | ME | 14 | DIRTY | 1 |

| APPLE | 820 | HURT | 96 | BUG | 12 | FUNNY | 1 |

| BLACK | 810 | GRAPES | 92 | PLANT | 12 | GLOVE | 1 |

| MASK | 723 | FRIEND | 82 | BRUSH | 11 | GREEN | 1 |

| GIMME | 680 | LAUGH | 80 | HEAR/LISTEN | 10 | HORSE | 1 |

| CHEESE | 623 | TOOTHBRUSH | 77 | PLEASE | 10 | HUG | 1 |

| CARROT | 602 | ICE CREAM | 76 | SHOE | 10 | NO | 1 |

| MEAT | 577 | BLANKET | 69 | DOG | 9 | NOSE | 1 |

| COFFEE | 504 | PEAR | 69 | EARRING | 8 | PEN/WRITE | 1 |

| MORE | 434 | WATER | 65 | GOOD | 8 | ROGER F. | 1 |

| NUT | 431 | POPCORN | 61 | HOT | 8 | SANTA | 1 |

| CEREAL | 387 | PAINT | 55 | WHITE | 8 | SICK | 1 |

| RED | 346 | QUIET | 52 | KISS | 7 | SLEEP | 1 |

| TREE | 304 | SORRY | 49 | DAR | 6 | SOON | 1 |

| OIL/LOTION | 300 | SLICE | 48 | GARBAGE | 6 | STUCK | 1 |

| GROOM | 274 | ORANGE | 47 | TOOTHPASTE | 6 | SURPRISE | 1 |

| CHASE | 271 | KEY | 45 | BED | 5 | THINK | 1 |

| PEACH | 264 | SANDWICH | 44 | HAIR | 5 | THIRSTY | 1 |

| CLEAN | 264 | BABY | 42 | CRY | 4 | TOMATO | 1 |

| ONION | 254 | COME | 42 | MINE/MY | 4 | WHO | 1 |

| SWEET | 250 | GUM | 42 | CAN’T | 3 | YELLOW | 1 |

| ICE/COLD | 240 | COOKIE | 40 | HUNGRY | 3 | ||

| BERRY | 220 | RICE | 37 | RADIO | 3 | ||

| LIPSTICK | 205 | CLOTHES | 34 | STUPID | 3 |

| CHASE | 1789 | GIMME | 91 | PERSON | 2 |

| THAT | 1683 | TICKLE | 32 | MASK | 2 |

| THERE | 1211 | COME | 13 | SWALLOW | 2 |

| HURRY | 1191 | GOOD | 13 | GO | 1 |

| YOU | 740 | TOOTHBRUSH | 8 | HUG | 1 |

| DRINK | 522 | KISS | 6 | NO | 1 |

| FOOD/EAT | 346 | CORN | 3 |

| Tatu | Loulis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Tokens | % Total Tokens | % Total Days | Total Tokens | % Total Tokens | % Total Days | |||

| 2014 | MILK | 258 | 5.86 | 91.17 | CHASE | 233 | 23.18 | 91.73 |

| DRINK | 235 | 5.33 | 83.04 | HURRY | 196 | 19.50 | 77.17 | |

| YOU | 197 | 4.47 | 69.61 | THAT | 193 | 19.20 | 75.98 | |

| THAT | 191 | 4.33 | 67.49 | YOU | 141 | 14.02 | 55.51 | |

| THERE | 180 | 4.09 | 63.60 | THERE | 76 | 7.56 | 29.92 | |

| 2015 | MILK | 210 | 6.54 | 81.71 | CHASE | 170 | 23.09 | 89.95 |

| CHEESE | 182 | 5.67 | 70.82 | THAT | 153 | 20.78 | 80.95 | |

| PERSON | 158 | 4.92 | 61.48 | YOU | 123 | 16.71 | 65.08 | |

| THAT | 157 | 4.89 | 61.09 | THERE | 119 | 16.16 | 62.96 | |

| YOU | 154 | 4.80 | 59.92 | HURRY | 100 | 13.58 | 52.91 | |

| 2016 | THAT | 180 | 5.22 | 75.63 | CHASE | 158 | 21.23 | 87.29 |

| THERE | 171 | 4.96 | 71.85 | THAT | 151 | 20.29 | 83.43 | |

| DRINK | 169 | 4.90 | 71.01 | THERE | 124 | 16.66 | 68.51 | |

| APPLE | 154 | 4.46 | 64.71 | HURRY | 106 | 14.24 | 58.56 | |

| YOU | 140 | 4.06 | 58.82 | YOU | 94 | 12.63 | 51.93 | |

| 2017 | THAT | 212 | 5.53 | 80.20 | CHASE | 277 | 26.81 | 96.60 |

| THERE | 204 | 5.32 | 66.34 | THAT | 203 | 19.65 | 86.38 | |

| DRINK | 194 | 5.06 | 62.38 | THERE | 160 | 15.48 | 68.09 | |

| PERSON | 191 | 4.98 | 55.45 | HURRY | 150 | 14.52 | 63.83 | |

| YOU | 187 | 4.88 | 55.45 | YOU | 116 | 11.22 | 49.36 | |

| 2018 | DRINK | 243 | 6.62 | 70.85 | CHASE | 317 | 24.78 | 92.42 |

| THAT | 201 | 5.48 | 58.6 | THAT | 298 | 23.29 | 86.88 | |

| PERSON | 189 | 5.15 | 55.10 | HURRY | 194 | 15.16 | 56.56 | |

| THERE | 168 | 4.58 | 48.98 | THERE | 188 | 14.69 | 54.81 | |

| YOU | 168 | 4.58 | 48.98 | YOU | 124 | 9.69 | 36.15 | |

| 2019 | DRINK | 274 | 7.39 | 87.82 | CHASE | 234 | 24.94 | 90.00 |

| PERSON | 246 | 6.63 | 78.85 | THAT | 220 | 23.45 | 84.62 | |

| THAT | 227 | 6.12 | 72.76 | THERE | 153 | 16.31 | 58.85 | |

| THERE | 205 | 5.53 | 65.71 | HURRY | 145 | 15.45 | 55.77 | |

| MILK | 189 | 5.09 | 60.58 | DRINK | 68 | 7.24 | 26.15 | |

| 2020 | DRINK | 245 | 8.38 | 89.74 | THAT | 226 | 24.35 | 95.36 |

| PERSON | 228 | 7.80 | 83.52 | CHASE | 219 | 23.59 | 92.41 | |

| THAT | 194 | 6.63 | 71.06 | THERE | 188 | 20.25 | 79.32 | |

| THERE | 187 | 6.39 | 68.50 | HURRY | 145 | 15.62 | 61.18 | |

| GO | 174 | 5.95 | 63.74 | DRINK | 70 | 7.54 | 29.54 | |

| 2021 | DRINK | 233 | 8.79 | 92.46 | CHASE | 230 | 24.23 | 93.12 |

| PERSON | 221 | 8.33 | 87.70 | THAT | 239 | 25.18 | 96.76 | |

| THAT | 169 | 6.37 | 67.06 | THERE | 203 | 21.39 | 82.19 | |

| CRACKER | 164 | 6.18 | 65.08 | HURRY | 155 | 16.33 | 62.75 | |

| THERE | 164 | 6.18 | 65.08 | DRINK | 80 | 8.42 | 32.39 |

| Category Subcategory | N n | % % |

|---|---|---|

| REQUESTS: solicit information, actions, or acknowledgment. | 34 | 25.95 |

| Yes-No questions: solicit the R to affirm, negate, or confirm the P of the S’s U. | 1 | 0.76 |

| Wh-questions: solicit information about the identity, location, or property of an object, event, or situation. | 1 | 0.76 |

| Action requests: solicit R to perform an act. | 32 | 24.43 |

| Permission requests: solicit R to grant permission for S to perform an act. | 0 | 0 |

| Rhetorical questions: solicit R’s acknowledgment for S to continue. | 0 | 0 |

| RESPONSES: directly complement preceding utterances. | 41 | 31.30 |

| Yes-No answers: complement yes-no questions. | 2 | 1.53 |

| Wh-answers: complement Wh-questions. | 16 | 12.21 |

| Agreements: agree with or deny the P of S’s previous U. | 12 | 9.16 |

| Compliances: make explicit compliances with action requests. | 5 | 3.82 |

| Qualifications: qualify, clarify, or otherwise change P of S’s U. | 6 | 4.58 |

| DESCRIPTIONS: represent observable or verifiable aspects of context. | 15 | 11.45 |

| Identifications: label an object, event, person, or situation. | 10 | 7.63 |

| Possessions: indicate who owns or temporarily possesses an object. | 0 | 0 |

| Events: represents the occurrence of an event, action, process, etc. | 0 | 0 |

| Properties: represent characteristics of objects, events, etc. | 0 | 0 |

| Locations: represent location or direction of objects, events, etc. | 5 | 3.82 |

| STATEMENTS: express analytic and institutional facts, beliefs, attitudes, emotions, reasons, etc. | 5 | 3.82 |

| Rules: express conventional procedures, facts, definitions, etc. | 0 | 0 |

| Evaluations: express impressions, attitudes, judgments, etc. | 1 | 0.76 |

| Internal reports: express S’s internal state (emotions, sentiments, sensations) | 4 | 3.05 |

| Attributions: express beliefs about another’s internal state. | 0 | 0 |

| Explanations: report reasons, causes, or motives for acts or predict future states of affairs. | 0 | 0 |

| CONVERSATIONAL DEVICES: regulate contact and conversations. | 36 | 27.48 |

| Boundary markers: initiate or end contact or conversation. | 19 | 14.50 |

| Calls: make contact by soliciting attention. | 3 | 2.29 |

| Accompaniments: signal contact by accompanying S’s action. | 7 | 5.34 |

| Returns: acknowledge, or fill in after, R’s preceding U. | 2 | 1.53 |

| Politeness markers: make explicit S’s politeness. | 5 | 3.82 |

| PERFORMATIVES: accomplish acts by being said. | 17 | 12.98 |

| Role play: establish fantasies. | 0 | 0 |

| Protests: object to R’s previous behavior. | 0 | 0 |

| Jokes: produce humorous effects. | 0 | 0 |

| Game markers: initiate, continue, or end a game. | 4 | 3.05 |

| Claims: establish rights for S by being signed. | 0 | 0 |

| Warnings: alert R of impending harm. | 0 | 0 |

| Teases: annoy, taunt, or provoke R. | 0 | 0 |

| Reassurance: calm, reassure, or provide support to R. | 13 | 9.92 |

| UNINTERPRETABLE: are unintelligible, incomplete, or otherwise incomprehensible utterances. | 9 | 6.87 |

| NO NARRATIVE: insufficient narrative included in sign log. | 6 | 4.58 |

| PRIVATE SIGN—no indication of interaction. | 2 | 1.53 |

| C-H | % | C-C | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requests | 24 | 26.97 | 10 | 13.70 |

| Responses | 40 | 44.94 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Descriptions | 14 | 15.73 | 1 | 1.37 |

| Statements | 2 | 2.25 | 3 | 4.11 |

| Conversational Devices | 6 | 6.74 | 30 | 41.10 |

| Performatives | 1 | 1.12 | 16 | 21.92 |

| Uninterpretable | 1 | 1.12 | 8 | 10.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jensvold, M.L.; Dombrausky, K.; Collins, E. Sign Language Studies with Chimpanzees in Sanctuary. Animals 2023, 13, 3486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13223486

Jensvold ML, Dombrausky K, Collins E. Sign Language Studies with Chimpanzees in Sanctuary. Animals. 2023; 13(22):3486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13223486

Chicago/Turabian StyleJensvold, Mary Lee, Kailie Dombrausky, and Emily Collins. 2023. "Sign Language Studies with Chimpanzees in Sanctuary" Animals 13, no. 22: 3486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13223486

APA StyleJensvold, M. L., Dombrausky, K., & Collins, E. (2023). Sign Language Studies with Chimpanzees in Sanctuary. Animals, 13(22), 3486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13223486