The Welfare of Dogs as an Aspect of the Human–Dog Bond: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Tale of Two Dogs

1.2. The Human–Dog Connection

1.2.1. The Human–Dog Bond

1.2.2. Function and the Human–Dog Bond

1.3. Dog Welfare Defined

1.4. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specifying the Research Question

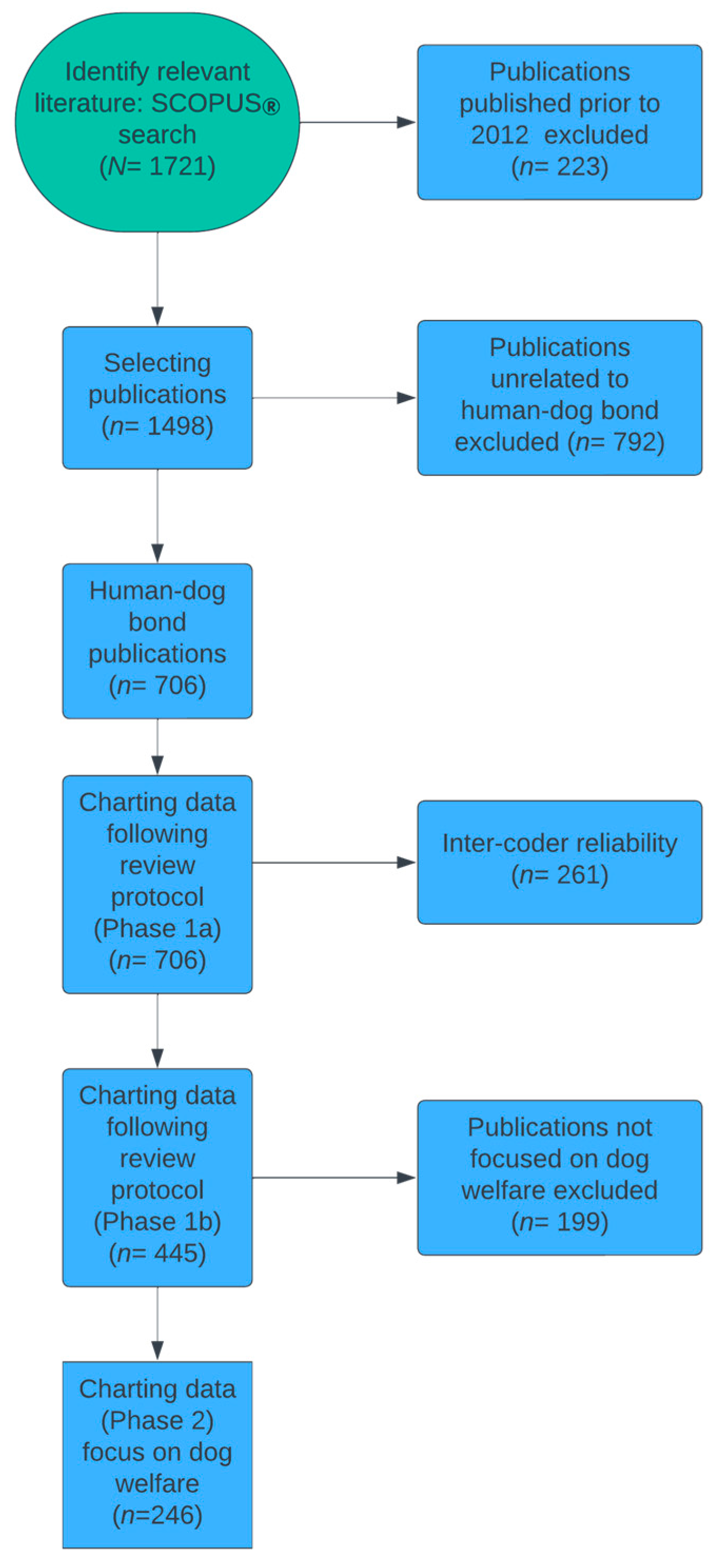

2.2. Identifying Relevant Literature

2.3. Selecting Publications

2.4. Charting the Data—Phase 1a

- (a)

- Primary focus of research/discussion on dog welfare.

- (b)

- Secondary/tertiary focus of research/discussion on dog welfare.

- (c)

- Dog welfare mentioned but not a focus of the research/discussion.

- (d)

- Dog welfare not mentioned in publication.

- (a)

- Pet dogs

- (b)

- Working dogs

- (c)

- Assistance/Service dogs

- (a)

- Owner (handler) [non-assistance/service dog]

- (b)

- Professional (e.g., K9 police officer; researcher, etc.)

- (c)

- Beneficiary (assistance/service dog)

2.4.1. Inter-Coder Reliability

2.4.2. Charting the Data—Phase 1b

2.4.3. Charting the Data—Phase 2

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Data

3. Results

3.1. Consideration of Dog Welfare in Human–Dog Bond Research Publications

3.1.1. Consideration of Dog Welfare by Category of Dog

3.1.2. Consideration of Dog Welfare by Country and Geographical Region

3.1.3. Top Journals Publishing Articles on the Human–Dog Bond with a Focus on Dog Welfare

3.1.4. Focus on Dog Welfare by Scientific Domain

3.2. Aspects of Dog Welfare

3.2.1. Aspects of Dog Welfare by Category of Dog

3.2.2. Aspects of Dog Welfare by Scientific Domain

3.2.3. Behavioral Aspects of Dog Welfare by Scientific Domain

4. Discussion

4.1. The Five-Domain Model of Dog Welfare and the Sentient Dog

4.1.1. The Pre-Acquisition Phase and Dog Welfare

4.1.2. Owner Characteristics and Dog Welfare

4.1.3. Problem Behaviors as a Dog Welfare Issue

4.1.4. Dog Training as a Dog Welfare Issue

4.1.5. Attachment to Owner as a Dog Welfare Issue

4.1.6. Dog Characteristics as a Dog Welfare Issue

4.1.7. Dog Emotion as a Dog Welfare Issue

4.2. Human–Dog Bond Research across the Globe

4.2.1. Focus on Dog Welfare in Context

4.2.2. Dog Welfare and the Function of Dogs

4.2.3. Reciprocity and Individual Differences

4.2.4. Crossing Disciplinary Boundaries

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pengelly, M. Trump VP Contender Kristi Noem Writes of Killing Dog–and Goat–in New Book. The Guardian, 26 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, N.; Beirne, P.; Horowitz, A.; Jones, I.; Kalof, L.; Karlsson, E.; King, T.; Litwak, H.; McDonald, R.A.; Murphy, L.J.; et al. Humanity’s Best Friend: A Dog-Centric Approach to Addressing Global Challenges. Animals 2020, 10, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, E.G.; McCune, S.; MacLean, E.; Fine, A. Our Canine Connection: The History, Benefits and Future of Human-Dog Interactions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 784491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koler-Matznick, J.; Adair, K.; Whittbecker, A. Dawn of the Dog: The Genesis of a Natural Species; Cynology Press: Mumbai, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, M.; Magyari, L.; Morvai, B.; Hernández-Pérez, R.; Dror, S.; Andics, A. Neural evidence for referential understanding of object words in dogs. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 1750–1754.e1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, A.; Cook, P.F.; Spivak, M.; Chhibber, R.; Berns, G.S. Awake fMRI Reveals Brain Regions for Novel Word Detection in Dogs. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chira, A.M.; Kirby, K.; Epperlein, T.; Brauer, J. Function predicts how people treat their dogs in a global sample. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsare, A.; Vanak, A.T. Modelling the challenges of managing free-ranging dog populations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waal, F.B.M.; Andrews, K. The question of animal emotions. Science 2022, 375, 1351–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, A.; D’Silva, J.; Duncan, I.; Palmer, N. Animal sentience: History, science, and politics. Anim. Sentience 2021, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, F. Mama’s Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us about Ourselves; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. viii, 326. [Google Scholar]

- Bekoff, M.; Goodall, J. The Emotional Lives of Animals: A Leading Scientist Explores Animal Joy, Sorrow, and Empathy—and Why They Matter; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, K. “All animals are conscious”: Shifting the null hypothesis in consciousness science. Mind Lang. 2024, 39, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrow, E.V.; Serpell, J.A.; Ostrander, E.A. Domestic dog lineages reveal genetic drivers of behavioral diversification. Cell 2022, 185, 4737–4755.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, K.; Hekman, J.; Li, X.; McClure, J.; Logan, B.; Goodman, L.; Gao, M.; Dong, Y.; Alonso, M.; Carmichael, E.; et al. Ancestry-inclusive dog genomics challenges popular breed stereotypes. Science 2022, 376, eabk0639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.E. Acquiring a Pet Dog: A Review of Factors Affecting the Decision-Making of Prospective Dog Owners. Animals 2019, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, E.M.C.; Vink, L.M.; Dijkstra, A. Social-Cognitive Processes Before Dog Acquisition Associated with Future Relationship Satisfaction of Dog Owners and Canine Behavior Problems. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Considering the “Dog” in Dog–Human Interaction. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 642821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekoff, M.; Pierce, J. Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible; New World Library: Novato, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pręgowski, M.P. Your Dog is Your Teacher: Contemporary Dog Training Beyond Radical Behaviorism. Soc. Anim. 2015, 23, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D.; Duffy, D.L.; Zawistowski, S.L.; Serpell, J.A. Behavioral and psychological characteristics of canine victims of abuse. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2015, 18, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro, C.; Reicher, V.; Kis, A.; Gacsi, M. Attachment towards the Owner Is Associated with Spontaneous Sleep EEG Parameters in Family Dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, G.; Noom, M.; Gazzano, A.; Mariti, C. Development of the Dog Attachment Insecurity Screening Inventory (D-AISI): A Pilot Study on a Sample of Female Owners. Animals 2021, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Aracena, L.; Grimm-Seyfarth, A.; Schüttler, E. Do dog-human bonds influence movements of free-ranging dogs in wilderness? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 241, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipple, N.; Thielke, L.; Smith, A.; Vitale, K.R.; Udell, M.A.R. Intraspecific and Interspecific Attachment between Cohabitant Dogs and Human Caregivers. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielke, L.E.; Udell, M.A.R. Evaluating Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes in Conjunction with the Secure Base Effect for Dogs in Shelter and Foster Environments. Animals 2019, 9, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A. Infantilizing Companion Animals through Attachment Theory: Why Shift to Behavioral Ecology-Based Paradigms for Welfare. Soc. Anim. 2020, 31, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.; Beetz, A.; Schoberl, I.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Attachment security in companion dogs: Adaptation of Ainsworth’s strange situation and classification procedures to dogs and their human caregivers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, E.; Bennett, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog-human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konok, V.; Kosztolanyi, A.; Rainer, W.; Mutschler, B.; Halsband, U.; Miklosi, A. Influence of owners’ attachment style and personality on their dogs’ (Canis familiaris) separation-related disorder. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. Interspecific behavioural synchronization: Dogs exhibit locomotor synchrony with humans. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. When walking in an outside area, shelter dogs (Canis familiaris) synchronize activity with their caregivers but do not remain as close to them as do pet dogs. J. Comp. Psychol. 2019, 133, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, C.L.; O’Neill, D.G.; Belshaw, Z.; Pegram, C.L.; Stevens, K.B.; Packer, R.M.A. Pandemic Puppies: Demographic Characteristics, Health and Early Life Experiences of Puppies Acquired during the 2020 Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK. Animals 2022, 12, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwell, E.G.; Panteli, E.; Krulik, T.; Dilley, A.; Root-Gutteridge, H.; Mills, D.S. Changes in Dog Behaviour Associated with the COVID-19 Lockdown, Pre-Existing Separation-Related Problems and Alterations in Owner Behaviour. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samet, L.E.; Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H.; Harvey, N.D.; Upjohn, M.M.; Casey, R.A. Exploring and Developing the Questions Used to Measure the Human-Dog Bond: New and Existing Themes. Animals 2022, 12, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopopova, A.; Mehrkam, L.R.; Boggess, M.M.; Wynne, C.D. In-kennel behavior predicts length of stay in shelter dogs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doring, D.; Nick, O.; Bauer, A.; Kuchenhoff, H.; Erhard, M.H. Behavior of laboratory dogs before and after rehoming in private homes. ALTEX-Altern. Anim. Exp. 2017, 34, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Collins, D.; Creevy, K.E.; Promislow, D.E.L.; Dog Aging Project, C. Age and Physical Activity Levels in Companion Dogs: Results From the Dog Aging Project. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 1986–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.D. The threads that bind us. Anat. Rec. 2021, 304, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotney, R.; Clay, L. Welfare of dogs and humans in animal-assisted interventions. In Animal-Assisted Interventions for Health and Human Service Professionals; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, J. Old friends make the best friends: A counter-narrative of aging for people and pets. J. Aging Stud. 2020, 54, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, E.; Mikkola, S.; Salonen, M.; Puurunen, J.; Sulkama, S.; Araujo, C.; Lohi, H. Active and social life is associated with lower non-social fearfulness in pet dogs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savalli, C.; Albuquerque, N.; Vasconcellos, A.S.; Ramos, D.; de Mello, F.T.; Mills, D.S. Assessment of emotional predisposition in dogs using PANAS (Positive and Negative Activation Scale) and associated relationships in a sample of dogs from Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkei, R.; Alvarez Gomez, S.; Pongracz, P. Fear vs. frustration-Possible factors behind canine separation related behaviour. Behav. Process. 2018, 157, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arahori, M.; Kuroshima, H.; Hori, Y.; Takagi, S.; Chijiiwa, H.; Fujita, K. Owners’ view of their pets’ emotions, intellect, and mutual relationship: Cats and dogs compared. Behav. Process. 2017, 141, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurachi, T.; Irimajiri, M.; Mizuta, Y.; Satoh, T. Dogs predisposed to anxiety disorders and related factors in Japan. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 196, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D. The psychobiology of social pain: Evidence for a neurocognitive overlap with physical pain and welfare implications for social animals with special attention to the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Physiol. Behav. 2016, 167, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiasvand, M.A.; Alimohammadi, S.; Hassanpour, S. Study of fear and fear evoking stimuli in a population of domestic dogs in Iran: A questionnaire-based study. Vet. Ital. 2022, 58, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, K.C. Separation, Confinement, or Noises: What Is Scaring That Dog? Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Sau, S.; Das, J.; Bhadra, A. Free-ranging dogs prefer petting over food in repeated interactions with unfamiliar humans. J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 220, 4654–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. Do shelter dogs engage in social referencing with their caregiver in an approach paradigm? An exploratory study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 189, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurer, J.M.; McKenzie, C.; Okemow, C.; Viveros-Guzman, A.; Beatch, H.; Jenkins, E.J. Who Let the Dogs Out? Communicating First Nations Perspectives on a Canine Veterinary Intervention Through Digital Storytelling. Ecohealth 2015, 12, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Angelo, D.; Sacchettino, L.; Quaranta, A.; Visone, M.; Avallone, L.; Gatta, C.; Napolitano, F. The Potential Impact of a Dog Training Program on the Animal Adoptions in an Italian Shelter. Animals 2022, 12, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira de Castro, A.C.; Araujo, A.; Fonseca, A.; Olsson, I.A.S. Improving dog training methods: Efficacy and efficiency of reward and mixed training methods. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Durston, T.; Flatman, J.; Kelly, D.; Moat, M.; Mohammed, R.; Smith, T.; Wickes, M.; Upjohn, M.; Casey, R. Impact of Socio-Economic Status on Accessibility of Dog Training Classes. Animals 2019, 9, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitulli, V.; Zanin, L.; Trentini, R.; Lucidi, P. Anthrozoology in Action: Performing Cognitive Training Paths in a Garden Shelter to Make Dogs More Suitable as Pets. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 23, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alers, E.V.; Simpson, K.M. Reclaiming identity through service to dogs in need. U.S. Army Med. Dep. J. 2012, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.; Miele, M.; Charles, N.; Fox, R. Becoming with a police dog: Training technologies for bonding. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2021, 46, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Dixon, L.; Buckley, L. Lead pulling as a welfare concern in pet dogs: What can veterinary professionals learn from current research? Vet. Rec. 2022, 191, e1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learn, A.; Radosta, L.; Pike, A. Preliminary assessment of differences in completeness of house-training between dogs based on size. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 35, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFollette, M.R.; Rodriguez, K.E.; Ogata, N.; O’Haire, M.E. Military Veterans and Their PTSD Service Dogs: Associations Between Training Methods, PTSD Severity, Dog Behavior, and the Human-Animal Bond. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, S.; de la Vega, S.; Gazzano, A.; Mariti, C.; Pereira, G.D.G.; Halsberghe, C.; Muser Leyvraz, A.; McPeake, K.; Schoening, B. Electronic training devices: Discussion on the pros and cons of their use in dogs as a basis for the position statement of the European Society of Veterinary Clinical Ethology. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 25, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.Y.; Albright, J.D.; Fine, A.H.; Peralta, J.M. Our Ethical and Moral Responsibility. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Benz-Schwarzburg, J.; Monso, S.; Huber, L. How Dogs Perceive Humans and How Humans Should Treat Their Pet Dogs: Linking Cognition With Ethics. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 584037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.K.; Leong, W.C.; Tan, J.S.; Hong, Z.W.; Chen, Y.L. Affective Recommender System for Pet Social Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 6759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccheddu, S.; Ronconi, L.; Albertini, M.; Coren, S.; Da Graca Pereira, G.; De Cataldo, L.; Haverbeke, A.; Mills, D.S.; Pierantoni, L.; Riemer, S.; et al. Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) grieve over the loss of a conspecific. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimarelli, G.; Marshall-Pescini, S.; Range, F.; Viranyi, Z. Pet dogs’ relationships vary rather individually than according to partner’s species. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Carlone, B.; Votta, E.; Ricci, E.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A. Intraspecific relationships in adult domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) living in the same household: A comparison of the relationship with the mother and an unrelated older female dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 194, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, T.; Nagasawa, M.; Mogi, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin promotes social bonding in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9085–9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Carlone, B.; Ricci, E.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A. Intraspecific attachment in adult domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Preliminary results. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, L.; Udell, M.A.R. Does Pet Parenting Style predict the social and problem-solving behavior of pet dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)? Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.E.; Mead, R.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. “Don’t Bring Me a Dog…I’ll Just Keep It”: Understanding Unplanned Dog Acquisitions Amongst a Sample of Dog Owners Attending Canine Health and Welfare Community Events in the United Kingdom. Animals 2021, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.R.; Wolff, L.M.; Bosworth, M.; Morstad, J. Dog and owner characteristics predict training success. Anim. Cogn. 2021, 24, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpotts, I.; Dillon, J.; Rooney, N. Improving the Welfare of Companion Dogs-Is Owner Education the Solution? Animals 2019, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ramirez, M.T. Compatibility between Humans and Their Dogs: Benefits for Both. Animals 2019, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehn, T.; Lindholm, U.; Keeling, L.; Forkman, B. I like my dog, does my dog like me? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, L.A. Make Me a Match: Prevalence and Outcomes Associated with Matching Programs in Dog Adoptions. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2021, 24, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.P.; Maia, C.M. Owners Frequently Report that They Reward Behaviors of Dogs by Petting and Praising, Especially When Dogs Respond Correctly to Commands and Play with Their Toys. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 23, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrkam, L.R.; Verdi, N.T.; Wynne, C.D. Human interaction as environmental enrichment for pair-housed wolves and wolf-dog crosses. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, J.; Crowley, S.L. Emotional Support Animal Partnerships: Behavior, Welfare, and Clinical Involvement. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudet, C.S.E.; Liu, K.; McElligott, A.G.; Cobb, M. Are children and dogs best friends? A scoping review to explore the positive and negative effects of child-dog interactions. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvinen, K.H.; Rhodes, R.E. Association Between Participation in Dog Agility and Physical Activity of Dog Owners. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, J. “My dog and I, we need the park”: More-than-human agency and the emergence of dog parks in Poland, 2015–2020. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 28, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Marvin, G.; Perkins, E. The Responsible Dog Owner: The Construction of Responsibility. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, N.; Kazanjian, A.; Borgen, W. Investing in human–animal bonds: What is the psychological return on such investment? Loisir Société/Soc. Leis. 2018, 41, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, N.H.; Brown, D.C.; Serpell, J.A. Associations between owner personality and psychological status and the prevalence of canine behavior problems. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, W.E.; Hicks, J.A.; Foster, C.L.; Holub, M.K.; Krecek, R.C.; Richburg, A.W. Attitudes and Motivations of Owners Who Enroll Pets in Pet Life-Care Centers. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.S.; Wright, H.F.; Mills, D.S. Parent perceptions of the quality of life of pet dogs living with neuro-typically developing and neuro-atypically developing children: An exploratory study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathurst, C.L.; Lunghofer, L. Lifetime bonds: At-risk youth and at-risk dogs helping one another. In Men and Their Dogs: A New Understanding of Man’s Best Friend; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sirois, L.M. Recovering for the loss of a beloved pet: Rethinking the legal classification of companion animals and the requirements for loss of companionship tort damages. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 2015, 163, 1199–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaidinho, J.; Valentin, G.; Tai, S.; Nguyen, B.; Sanders, K.; Jackson, M.; Gilbert, E.; Starner, T. Leveraging Mobile Technology to Increase the Permanent Adoption of Shelter Dogs. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–27 August 2015; pp. 463–469. [Google Scholar]

- App that rewards owners for good dog care. Vet. Rec. 2023, 192, 63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.; Stefanovski, D.; Siracusa, C.; Serpell, J. Owner Personality, Owner-Dog Attachment, and Canine Demographics Influence Treatment Outcomes in Canine Behavioral Medicine Cases. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 630931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirrone, F. The importance of educating prospective dog owners on best practice for acquiring a puppy. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, C.; Burrows, H.; Zulch, H. Educating owners isn’t enough to prevent behavioural problems. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.S.; Finka, L.; Mills, D.S. A systematic scoping review: What is the risk from child-dog interactions to dog’s quality of life? J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 33, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardoia, M.; Arena, L.; Berteselli, G.; Migliaccio, P.; Valerii, L.; Di Giustino, L.; Dalla Villa, P. Development of a questionnaire to evaluate the occupational stress in dog’s shelter operators. Vet. Ital. 2019, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickler, B.G. Helping Pet Owners Change Pet Behaviors: An Overview of the Science. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.; Starling, M.; Payne, E.; Bennett, P. Defining and measuring dogmanship: A new multidisciplinary science to improve understanding of human-dog interactions. Vet. J. 2017, 229, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diverio, S.; Boccini, B.; Menchetti, L.; Bennett, P.C. The Italian perception of the ideal companion dog. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 12, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, M.E.; Lord, L.K.; Husseini, S.E. Effects of preadoption counseling on the prevention of separation anxiety in newly adopted shelter dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiplady, C.M.; Walsh, D.B.; Phillips, C.J. Intimate partner violence and companion animal welfare. Aust. Vet. J. 2012, 90, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaataja, H.; Majaranta, P.; Cardo, A.V.; Isokoski, P.; Somppi, S.; Vehkaoja, A.; Vainio, O.; Surakka, V. The Interplay Between Affect, Dog’s Physical Activity and Dog-Owner Relationship. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 673407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuma, P.; Fowler, J.; Duerr, F.; Kogan, L.; Stockman, J.; Graham, D.J.; Duncan, C. Promoting Outdoor Physical Activity for People and Pets: Opportunities for Veterinarians to Engage in Public Health. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2019, 34, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.C.; Withers, A.M.; Spencer, J.; Norris, J.M.; Ward, M.P. Evaluation of a Dog Population Management Intervention: Measuring Indicators of Impact. Animals 2020, 10, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, C.; Dzik, V.; Carballo, F.; Bentosela, M. Post-Conflict Affiliative Behaviors Towards Humans in Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris). Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2016, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbacher, E.N.; Muir, K.L. Using Owner Return as a Reinforcer to Operantly Treat Separation-Related Problem Behavior in Dogs. Animals 2020, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.C.; Zito, S.; Thomas, J.; Dale, A. Post-Adoption Problem Behaviours in Adolescent and Adult Dogs Rehomed through a New Zealand Animal Shelter. Animals 2018, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wormald, D.; Lawrence, A.J.; Carter, G.; Fisher, A.D. Reduced heart rate variability in pet dogs affected by anxiety-related behaviour problems. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 168, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielke, L.E.; Udell, M.A. The role of oxytocin in relationships between dogs and humans and potential applications for the treatment of separation anxiety in dogs. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2017, 92, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.; van der Zee, E.; Zulch, H. When the Bond Goes Wrong. In The Social Dog; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens-Lewis, D.; Johnson, A.; Turley, N.; Naydorf-Hannis, R.; Scurlock-Evans, L.; Schenke, K.C. Understanding Canine ‘Reactivity’: Species-Specific Behaviour or Human Inconvenience? J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2022, 27, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bram Dube, M.; Asher, L.; Wurbel, H.; Riemer, S.; Melotti, L. Parallels in the interactive effect of highly sensitive personality and social factors on behaviour problems in dogs and humans. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrkam, L.R.; Perez, B.C.; Self, V.N.; Vollmer, T.R.; Dorey, N.R. Functional analysis and operant treatment of food guarding in a pet dog. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2020, 53, 2139–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.; Duffy, D.L.; Kruger, K.A.; Watson, B.; Serpell, J.A. Relinquishing Owners Underestimate Their Dog’s Behavioral Problems: Deception or Lack of Knowledge? Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 734973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normando, S.; Bertomoro, F.; Bonetti, O. Satisfaction and satisfaction affecting problem behavior in different types of adopted dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.R.; Hall, N.J. Effect of greeting and departure interactions on the development of increased separation-related behaviors in newly adopted adult dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2021, 41, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Webb, L.; Montrose, V.T.; Williams, J. The behavioral and physiological effects of dog appeasing pheromone on canine behavior during separation from the owner. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 40, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, K.; Ballantyne, K.C. Living with and loving a pet with behavioral problems: Pet owners’ experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinwoodie, I.R.; Dwyer, B.; Zottola, V.; Gleason, D.; Dodman, N.H. Demographics and comorbidity of behavior problems in dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 32, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canejo-Teixeira, R.; Neto, I.; Baptista, L.V.; Niza, M. Identification of dysfunctional human-dog dyads through dog ownership histories. Open Vet. J. 2019, 9, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapaksha, E. Special Considerations for Diagnosing Behavior Problems in Older Pets. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koda, N.; Watanabe, G.; Miyaji, Y.; Ishida, A.; Miyaji, C. Stress levels in dogs, and its recognition by their handlers, during animal-assisted therapy in a prison. Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, G.; Borrelli, C.; Campera, M.; Gazzano, A.; Mariti, C. Physiological Indicators of Acute and Chronic Stress in Securely and Insecurely Attached Dogs Undergoing a Strange Situation Procedure (SSP): Preliminary Results. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariti, C.; Pierantoni, L.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A. Guardians’ Perceptions of Dogs’ Welfare and Behaviors Related to Visiting the Veterinary Clinic. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2017, 20, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsly, M.; Priymenko, N.; Girault, C.; Duranton, C.; Gaunet, F. Dog behaviours in veterinary consultations: Part II. The relationship between the behaviours of dogs and their owners. Vet. J. 2022, 281, 105789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, L.R.; Hellyer, P.W.; Rishniw, M.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R. Veterinary Behavior: Assessment of Veterinarians’ Training, Experience, and Comfort Level with Cases. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2020, 47, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoltova, E.; Martineau, M.; Boissy, A.; Gilbert, C. Behavioral and physiological reactions in dogs to a veterinary examination: Owner-dog interactions improve canine well-being. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 177, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, D.; Haberland, B.E.; Ossig, A.; Küchenhoff, H.; Dobenecker, B.; Hack, R.; Schmidt, J.; Erhard, M.H. Behavior of laboratory beagles towards humans: Assessment in an encounter test and a simulation of experimental situations. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.M.; Martin, D.; Shaw, J.K. Small animal behavioral triage: A guide for practitioners. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 44, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, E.M.C.; Vink, L.M.; Dijkstra, A. Expectations versus Reality: Long-Term Research on the Dog-Owner Relationship. Animals 2020, 10, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, hope and charity: How low-cost veterinary clinics make a difference. Vet. Rec. 2020, 186, 655. [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Primary Focus | Secondary Focus | Dog Welfare Mentioned | Dog Welfare Not Mentioned | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 10 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| 2014 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 16 | 34 |

| 2015 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 28 | 46 |

| 2016 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 28 | 51 |

| 2017 | 13 | 15 | 21 | 37 | 86 |

| 2018 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 35 | 61 |

| 2019 | 19 | 13 | 23 | 46 | 101 |

| 2020 | 21 | 21 | 17 | 47 | 106 |

| 2021 | 28 | 28 | 24 | 33 | 113 |

| 2022 | 20 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 58 |

| Total | 135 | 102 | 138 | 305 | 680 |

| % | 19.9 | 15 | 20.3 | 44.8 | 100 |

| 2023 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 26 |

| % | 26.9 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 50 | 100 |

| Category | Pet Dogs | Working Dogs | Service Dogs | Mixed Sample | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | 129 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 142 |

| Secondary Focus | 95 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 104 |

| Dog Welfare Mentioned | 105 | 4 | 27 | 6 | 142 |

| Dog Welfare Not Mentioned. | 241 | 11 | 51 | 15 | 318 |

| Total | 570 | 24 | 87 | 25 | 706 |

| Africa | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| Burkina Faso | 1 | 1 | |||

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ethiopia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Nigeria | 1 | 1 | |||

| Rwanda | 1 | 1 | |||

| South Africa | 1 | 1 | |||

| Subtotal (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.6) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (100) |

| Asia | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| China | 2 | 2 | |||

| Hong Kong | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| India | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | |

| Japan | 2 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 19 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 | |||

| Philippines | 1 | 1 | |||

| South Korea | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | |||

| Taiwan | 1 | 1 | |||

| Thailand | 1 | 1 | |||

| Subtotal (%) | 6 (16.2) | 6 (16.2) | 8 (21.6) | 17 (45.9) | 37 (100) |

| Europe | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| Austria | 1 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 22 |

| Belgium | 2 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Czech Republic | 4 | 4 | |||

| Denmark | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| Finland | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| France | 8 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 19 |

| Germany | 5 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 15 |

| Greece | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hungary | 3 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 18 |

| Ireland | 2 | 2 | |||

| Italy | 13 | 4 | 5 | 26 | 48 |

| The Netherlands | 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 19 |

| Northern Ireland | 1 | 1 | |||

| Norway | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Poland | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Romania | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Russia | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Serbia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Slovenia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Spain | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| Sweden | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 14 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | |

| UK | 25 | 16 | 25 | 22 | 88 |

| Subtotal (%) | 73 (24.3) | 41 (13.6) | 55 (18.3) | 132 (43.8) | 301 (100) |

| Middle East | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| Iran | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Subtotal (%) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (100) | ||

| North America | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| Canada | 4 | 10 | 9 | 14 | 37 |

| USA | 47 | 29 | 50 | 114 | 240 |

| Subtotal (%) | 51 (18.4) | 39 (14.1) | 59 (21.3) | 128 (46.2) | 277 (100) |

| Oceania | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| Australia | 6 | 8 | 8 | 26 | 48 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Subtotal (%) | 7 (13.5) | 9 (17.3) | 9 (17.3) | 27 (51.9) | 52 (100) |

| South America | Primary | Secondary | Mentioned | Not Mentioned | Total |

| Argentina | 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | |

| Brazil | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Chile | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Mexico | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Subtotal (%) | 4 (13.3) | 8 (26.7) | 8 (26.7) | 10 (33.3) | 30 (100) |

| Journal | Primary Focus | Secondary Focus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animals | 13 | 11 | 24 |

| Scientific Reports | 12 | 1 | 13 |

| Frontiers in Veterinary Science | 11 | 8 | 19 |

| Journal of Veterinary Behavior | 11 | 8 | 19 |

| Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Veterinary Clinics of N. America—Small Animal Practice | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| PLoS ONE | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Veterinary Record | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Veterinary Sciences | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Applied Animal Behavior Science | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Physiology and Behavior | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Preventive Veterinary Medicine | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Society and Animals | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Animal Cognition | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| International Journal of Comparative Psychology | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Topics in Companion Animal Medicine | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Veterinary Journal | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Anthrozoös | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Journal of Comparative Pathology | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Science Domain: | Behavior | Welfare | Medical | Social | Veterinary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | 37 | 13 | 10 | 16 | 66 |

| Secondary Focus | 21 | 1 | 26 | 23 | 33 |

| Dog Welfare Mentioned | 35 | 5 | 40 | 34 | 28 |

| Dog Welfare Not Mentioned | 93 | 5 | 88 | 99 | 33 |

| Total | 186 | 24 | 164 | 172 | 160 |

| Pet Dogs | Working Dogs | Service Dogs | Mixed Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Environment | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health | 82 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Behavior | 103 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 224 | 9 | 9 | 4 |

| Behavior | Welfare | Medical | Social | Veterinary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| Environment | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Health | 9 | 0 | 27 | 7 | 47 |

| Behavior | 39 | 11 | 5 | 25 | 34 |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 58 | 14 | 36 | 39 | 99 |

| (a) | |||||||

| Science Domain: | Behavior | Welfare | Medical | Social | Veterinary | Total | |

| Behavioral interactional effects associated with: | |||||||

| Abuse | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Attachment | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

| Synchrony | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Dog characteristics | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 8 | |

| Dog emotion | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 8 | |

| Dog preferences | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Dog-related injuries | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Dog training | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 11 | |

| Ethical/moral issues | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Intraspecies interactions | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Owner characteristics | 7 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 11 | 34 | |

| Physical activity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Population management | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Post-conflict behavior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Problem behaviors | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 16 | |

| Stress levels | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Veterinary visits | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | |

| Total | 39 | 11 | 5 | 25 | 34 | 114 | |

| (b) | |||||||

| Scientific Domain | Behavior | Welfare | Medical | Social | Veterinary | ||

| Abuse | - | McMillan et al. [24] | - | - | - | ||

| Attachment | Carreiro et al. [25]; Riggio et al. [26]; Saavedra-Aracena et al. [27]; Sipple et al. [28]; Thielke and Udell [29] | - | - | Lewis [30]; Solomon et al. [31]; Payne et al. [32]; Konok et al. [33]; | |||

| Behavioral synchrony | Duranton et al. [34] | - | - | Duranton et al. [35] | - | ||

| COVID-19 pandemic | Brand et al. [36] | - | - | - | Sherwell et al. [37] | ||

| Dog characteristics | Samet et al. [38]; Protopopova et al. [39] | Döring et al. [40] | Lee et al. [41]; Smith [42]; Scotney and Clay [43] | Chira et al. [7]; Yamasaki [44] | - | ||

| Dog emotion | Hakanen et al. [45]; Savalli et al. [46]; Lenkei et al. [47]; Arahori et al. [48]; Kurachi et al. [49] | - | - | McMillan [50] | Qiasvand et al. [51]; Ballantyne [52] | ||

| Dog preferences | Bhattacharjee et al. [53]; Duranton et al. [54] | - | - | - | - | ||

| Dog-related human injuries | - | - | Schurer et al. [55] | - | - | ||

| Dog training | D’Angelo et al. [56]; Vieira de Castro et al. [57]; Harris et al. [58] | Vitulli et al. [59] | Alers & Simpson [60] | Smith et al. [61]; Pręgowski [23] | Townsend et al. [62]; Learn et al. [63]; LaFollette et al. [64]; Masson et al. [65]; | ||

| Ethical/moral issues | NG et al. [66] | - | - | Benz-Schwarzburg et al. [67] | - | ||

| Intraspecies interaction | Cheng et al. [68]; Uccheddu et al. [69]; Cimarelli et al. [70]; Mariti et al. [71]; Romero et al. [72]; Mariti et al. [73] | - | - | - | - | ||

| Owner/handler characteristics | Brubaker and Udell [74]; Holland et al. [75]; Stevens et al. [76]; Holland [16]; Philpotts et al. [77]; González-Ramírez [78]; Rehn et al. [79] | Reese [80]; Rossi and Maia [81]; Mehrkam et al. [82] | - | Ferrell and Crowley [83]; Giraudet et al. [84]; Karvinen and Rhodes [85]; Włodarczyk [86]; Bouma et al. [17]; Westgarth et al. [87]; Maharaj et al. [88]; Dodman et al. [89]; Davis et al. [90]; Hall et al. [91]; Bathurst and Lunghofer [92]; Sirois [93]; Alcaidinho et al. [94] | The Veterinary Record [95]; Powell et al. [96]; Pirrone [97]; Laurence et al. [98]; Hall et al. [99]; Nardoia et al. [100]; Strickler [101]; McGreevy et al. [102]; Diverio et al. [103]; Herron et al. [104]; Tiplady et al. [105]; | ||

| Physical activity | - | - | - | - | Väätäjä et al. [106]; Yuma et al. [107] | ||

| Population management | Ma et al. [108] | - | - | - | - | ||

| Post-conflict behavior | - | - | - | Cavalli et al. [109] | - | ||

| Problem behavior | Feuerbacher and Muir [110]; Gates et al. [111]; Wormald et al. [112]; Thielke and Udell [113]; Mills et al. [114] | Stephens-Lewis et al. [115]; Bräm Dubé et al. [116]; Mehrkam et al. [117] | - | - | Powell et al. [118]; Normando et al. [119]; Teixeira and Hall [120]; Taylor et al. [121]; Buller and Ballantine [122]; Dinwoodie et al. [123]; Canejo-Teixeira et al. [124]; Rajapaksha [125] | ||

| Stress levels | - | Koda et al. [126] | - | - | Riggio et al. [127] | ||

| Veterinary visits | - | Mariti et al. [128] | - | - | Helsly et al. [129]; Kogan et al. [130]; Csoltova et al. [131]; Döring et al. [132]; Martin et al. [133] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verbeek, P.; Majure, C.A.; Quattrochi, L.; Turner, S.J. The Welfare of Dogs as an Aspect of the Human–Dog Bond: A Scoping Review. Animals 2024, 14, 1985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14131985

Verbeek P, Majure CA, Quattrochi L, Turner SJ. The Welfare of Dogs as an Aspect of the Human–Dog Bond: A Scoping Review. Animals. 2024; 14(13):1985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14131985

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerbeek, Peter, Chase Alan Majure, Laura Quattrochi, and Stephen James Turner. 2024. "The Welfare of Dogs as an Aspect of the Human–Dog Bond: A Scoping Review" Animals 14, no. 13: 1985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14131985