Experiences of Interdisciplinary Working from the Perspective of the Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Thematic Analysis

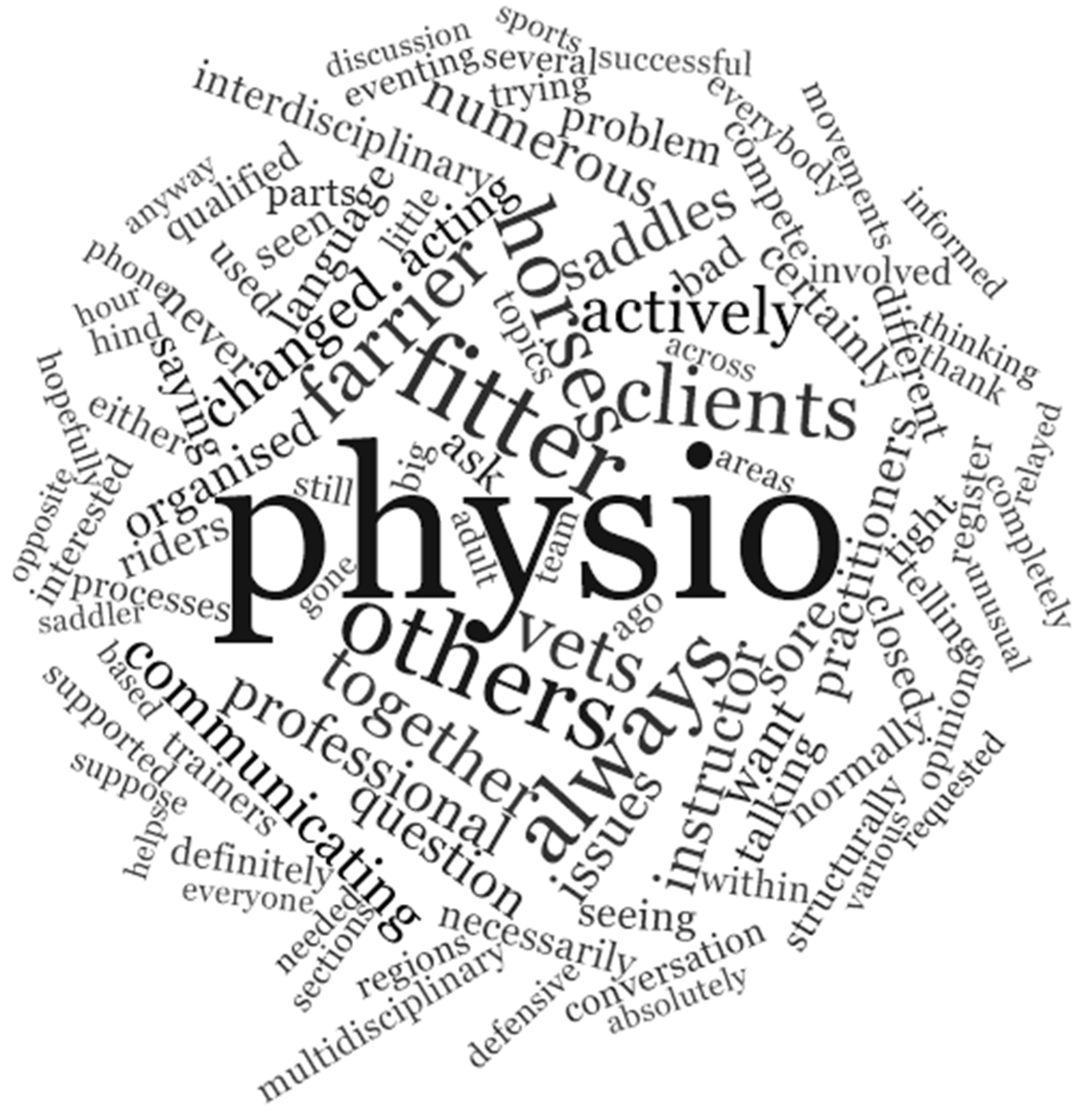

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Effective Communication

I contacted said physio ……… she’s in the area, we know each other, we’ve talked in the past about previous horses. And it transpired that there was X, Y and Z going on with the horse and actually it was a Chinese whispers thing, what I’ve been told from the customer wasn’t actually what the physio had said to the customer. So, in actual fact having a relationship with that physio meant I could pick up the phone and say, what’s going on, and get it from the horse’s mouth…

I’d ask the customer to get them to phone me, …… quite often you might say that and no one will bother phoning. I don’t [know]… Um, one in ten [will telephone]

I think it’s about knowing who else is involved, so who’s on your team, it’s about that team having good lines of communication and it’s about understanding what you’re supposed to be looking at and what other people are supposed to be looking at.

If everyone communicates their point…. I think you should always take from other people rather than trying to push your opinions on them.

3.2. Theme 2: Multidisciplinary Expectations

But I think the expectation from customers a lot of the time is that you get a saddle and that should be it and it should be perfect and you should never ever have a problem…. I think expectation versus reality is very different.

I think for me with my customers, there’s a split, there’s a real divide there with people that are, that want it, know about it and are trying to achieve it, and people that have no idea. I should, we should be educating them…… You know, and that’s only because they don’t know, they don’t know that a physio alongside the vet, alongside that saddle fitter, alongside the farrier can actually make everything all so much nicer and easier, they genuinely don’t know that.

I think they’re beginning to expect this sort of thing, but it’s taking a while…. I’m trying to educate my clients.

3.3. Theme 3: Horse Welfare

I think the biggest advantage is that what the vet and the physio will generally not see is the horse being ridden, and I think the saddle fitter and the instructor will observe the horse under saddle.

[It is] partly because ……. horses are really, really forgiving and, you know, I think a common perception is my horse is not misbehaving, therefore I don’t need to get my saddle checked.

It’s for the welfare of the horse. It’s, the horse is, you know, everything is linked, it’s not just, you can’t just do a saddle fitting and think that that’s going to fix everything else that’s wrong with the horse. You know, you need everybody else there to have their input as well. And it’s all about making the horse as comfortable as possible, isn’t it?

The main advantage is a better looked after horse……. a happier, healthier horse with a rider that’s more balanced.

3.4. Theme 4: Professional

- (i).

- Professional boundaries

It’s always trying to remind people that if you’re a qualified saddle fitter, you’re not a qualified physio so you can’t comment on any physio/veterinary issues but at the same time, the physio is not necessarily a qualified saddle fitter, so they shouldn’t really be commenting on saddle fit in any particular detail. If they don’t think it fits, then they should be saying, I don’t think it fits, or, I suggest you get your saddle fitter to check it. But they shouldn’t be saying, oh, this doesn’t fit because…

I think the first thing a multidisciplinary team has to do is, each person has to understand what their area of expertise is and where the boundaries are, and where they need to, whether they have information or they have an observation that would be beneficial to be shared with another member of that, that team.

- (ii).

- Decision making

The horse in question, in my opinion, needed to be investigated by the vet…. as a saddle fitter it’s really hard to advise [on] veterinary intervention.

- (iii).

- Professional representation

…I don’t think that saddle fitting is seen as a profession in the same way that being a qualified physiotherapist or a qualified vet.

I’d probably seek advice from other fitters, or just to be able to, you know, to talk it through, see what their opinion is, if there’s anything else they’d try.

3.5. Theme 5: Relationships

Yes, I would say the majority of them [clients] are loyal, … So, it’s me they’re seeing and I like to think that I build quite a good relationship with most of my customers. You always get the odd person that is only out for the person that can, you know, see them the quickest or the cheapest, but I do have quite a regular customer base of people that come back to me, so I would like to think that they are loyal.

…I have a particularly good relationship with this customer…. And because I had a good relationship with her, she was open to me talking [to the vet]

So, as I just mentioned before, you know, being able to put things into words for another professional to understand and to have that relationship and rapport.

3.6. Theme 6: Working Together

…. I think the first thing and the major thing is that I think saddle fitting in general is massively undervalued, that some people get it and some people don’t, and I think both owners and other practitioners don’t, don’t value saddle fitting, as being particularly, not, not, it’s not, important isn’t the word, but I don’t think they see it as relevant, as being as relevant as, you know, things that involve actually treating the horse like the vet and the physio would do.

I have found that quite difficult to arrange a lot of the times, I suppose because around here we do cover such vast areas and we both, you know, I say both, me and whichever one of the others, are booked quite far in advance. It’s quite difficult to coordinate our diaries to do that, so normally it’s done by email or phone to be honest.

I think I’d like to see something a bit more official, because I never really know whether I’m supposed to discuss other people and other people’s horses with other practitioners, I don’t actually know what the proper protocol is.

I mean I think your biggest problem is the money, is the money.

…if the client can see pound notes flying out the window, they’re going to be a little bit reluctant

I do find resistance to any investigation by vets. They tend to be more amenable to [the] thoughts of physios.

The advantages are obviously that you can get a much wider knowledge base providing possible modifications and suggesting possible outcomes for each modification. So, the advantage is more knowledge, obviously.

Unless we have more understanding of one another’s areas, …we can’t work together. And I’m not saying that we all need to be an expert in every single field because that’s clearly not the case, and that’s clearly not possible.

Do we not think that word, education, is the key? Do we not, personally, again, I can only go from opinion, can’t I? But personally, unless, unless we have more understanding of one another’s areas, we can’t, we can’t work together.

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Greater understanding of how a team-based approach impacts horse welfare: Given that professions other than saddle fitters have the opportunity to influence saddle fit, better understanding of how all those within the MDT currently engage with horse owners could inform strategies for more effective MDT engagement on saddle fit matters. Indeed, the study of how equestrian professionals engage with each other and the horse owner on saddle fit matters, could be used as a model for improvements in MDT working on other equine health and welfare issues. As seen in human healthcare MDTs, an appreciation and recognition of the professional scope of practitioners by all professions within the team is essential to successful MDT working.

- (2)

- How to build effective inter-disciplinary relationships and communication across flexible teams: Each profession knowing when to consult and refer to others within the team aids inter-disciplinary relationships, so “professional relationships” should feature in the education programmes of those within the MDT. Recent work suggests that in a veterinary education environment, peer-assisted learning can be successful [41]. Practical strategies to provide opportunity for cross-disciplinary education programmes may be welcomed by those within MDTs and foster more-effective learning and greater cooperation between professions. This study indicated practical barriers centred on resources, including time and money, and effective modes of communication as challenges to a successful MDT-based approach. Some participants gave examples of using social media platforms such as WhatsApp groups to share information. The potential benefits and pitfalls of utilizing digital spaces to safely share images and video and to communicate with other professionals and the horse owner is worthy of investigation in an increasingly time-pressured working environment.

- (3)

- The role of the horse owner within the MDT: Acceptance of the horse owner as an essential contributor to the MDT is considered fundamental to a successful MDT but complex and differentiated according to the situation, the horse owner, and the professionals involved. This work suggests that there may be gaps in some horse owners’ understanding of the significance of saddle fit to horse welfare or misinformation provided by unregulated sources. The person taking on the leadership or central role in the MDT should have a high degree of knowledge. Education of horse owners by reliable sources may be a useful step towards increased owner awareness and responsibility for saddle fit. Again, effective, targeted, and evidence-based social media programmes have potential to be leveraged to this effect [42]. The role of the horse owner within the MDT; whether or not they should assume greater responsibility; and the barriers, challenges, and opportunities of the horse owner in a leadership role within the MDT comprise an exciting area for further work and one with potential for outcomes with practical implications for positive welfare outcomes for the ridden horse.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Probing/Prompts Questions Questioning Technique |

|---|---|

| Context Opening question: Tell me a bit about yourself, your experience, how and when you qualified. | |

| Tell me about your business operation. How do you work? | How many, if any, staff do you employ? Which geographical regions do you cover? |

| Tell me about your client base. | Are your clients mostly professional or leisure? If they compete, in which disciplines? Do you feel that your client are loyal to you and your business? |

| When did you last work with another type of practitioner eg vet, farrier, physio etc. | How easy was it to co-ordinate working with other practitioners/professionals? Talk me through the process. |

| How frequently do you work with other practitioners ? | Please name which professionals you have worked with. On a monthly basis/annual? |

| Do you work directly with these professionals or do you co-ordinate the work through others (such as your client)? | Tell me about how this works Tell me about the process. |

| What does the term interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary team working mean to you? | Have you come across this term before, if so, in what context? Could you define the term to me? |

| Who would you perceive to be in a multi-disciplinary team with you? | Remind participant to include all professional groups they have worked with. |

| What do you perceive to be the advantages and disadvantages of multidisciplinary team working? | Contextualised for the equine sector and more broadly |

| Do you feel that your clients have an expectation that inter-disciplinary team working will be available? | Can you outline your thoughts? What you do think about this? |

| Has there ever been an occasion when multidisciplinary working in this way has not gone well or has been unsatisfactory? | Critical incident discussion What happened? Did you feel let down? Do you think the other practitioner/client feel let down? What was the outcome? How could it have been different? |

| Has there ever been an occasion when multidisciplinary team working has surpassed all of your expectations? | Critical incident discussion What happened? Can you explain why you feel this way? What did the participants do to make this process so good? |

| Have you experienced any barriers to interdisciplinary working? | Please take me through your experiences Can you give me any examples? |

| Based on your experience, what is your opinion of working with other practitioners? | Can you elaborate with experience/occasions which have shaped your opinion? |

| Do you feel that the profession should be working with other practitioners? | Please can you explain why you feel this way? Do you think that clients may influence how services are provided/offered? |

| Could interdisciplinary working be improved in any way? Can you explain how? | Please elaborate on your thoughts |

| Closing questions/opportunity for participant to make additional comments | Is there anything that you would like to add? Anything that you feel is important that you have not had the opportunity to discuss or what wish to add to our discussions today? |

References

- The British Equestrian Trade Association. National Equestrian Survey. 2023. Available online: https://www.nationalequineforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NEF23-BETA-The-National-Equestrian-Survey-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Taberna, M.; Gil Moncayo, F.; Jané-Salas, E.; Antonio, M.; Arribas, L.; Vilajosana, E.; Peralvez Torres, E.; Mesía, R. The multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach and quality of care. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrill, C.; West, M.; Shapiro, D.; Rees, A. Team working and effectiveness in health care. Br. J. Healthc. Manag. 2000, 6, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, W.A.; Werner, H.W.; O’Grady, S.E.; Ridley, J.T. The veterinary–farrier relationship: Establishing and sustaining a mutually beneficial liaison. Equine Vet. Educ. 2018, 30, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, C.M.; Stubbs, N.C.; Jull, G.A. Equine physiotherapy: A comparative view of the science underlying the profession. Equine Vet. J. 2007, 39, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veterinary Surgeons Act. 1966. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1966/36 (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Farriers (Registration) Act. 2017. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2017/28/contents (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- The Veterinary Surgery (Exemptions) Order. 2015. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/772 (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- The Equine Fitters Council. Available online: https://www.equinefittersdirectory.org/what-we-do/ (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Dyson, S.; Carson, S.; Fisher, M. Saddle fitting, recognising an ill-fitting saddle and the consequences of an ill-fitting saddle to horse and rider. Equine Vet. Educ. 2015, 27, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horseman, S.V.; Buller, H.; Mullan, S.; Whay, H.R. Current welfare problems facing horses in Great Britain as identified by equine stakeholders. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, H.M.; MacKechnie-Guire, R. Tack Fit and Use. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2022, 38, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwal, A.; Caldwell, K. Do all health and social care professionals interact equally: A study of interactions in multidisciplinary teams in the United Kingdom. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2005, 19, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.; Garside, P.; Black, A. Multidisciplinary team working, clinical networks, and chambers; opportunities to work differently in the NHS. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2003, 12 (Suppl. S1), i25–i28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lynden, J.; Ogden, J.; Hollands, T. Contracting for care–the construction of the farrier role in supporting horse owners to prevent laminitis. Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, K.L.; Verheyen, K.L.P. Associations between physiotherapy findings and subsequent diagnosis of pelvic or hindlimb fracture in racing Thoroughbreds. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, L.; Dyson, S.J. An investigation of the relationship between hindlimb lameness and saddle slip. Equine Vet. J. 2013, 45, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, L.; Dyson, S.J. The interrelationship of lameness, saddle slip and back shape in the general sports horse population. Equine Vet. J. 2014, 46, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, T.; Christley, R. Study design synopsis: From the horse’s mouth: Qualitative methods for equine veterinary research. Equine Vet. J. 2021, 53, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.F. Discovering new areas of veterinary science through qualitative research interviews: Introductory concepts for veterinarians. Aust. Vet. J. 2018, 96, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christley, R.M.; Perkins, E. Researching hard to reach areas of knowledge: Qualitative research in veterinary science. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Hannes, K.; Harden, A.; Noyes, J.; Harris, J.; Tong, A. COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies). Guidel. Report. Health Res. A User’s Man. 2014, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazeley, P. Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies. In Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–584. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnison, T.; May, S.A.; Guile, D. Inter-professional practice: From veterinarian to the veterinary team. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2014, 41, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.E.; Arroyo, L.G.; Renaud, D.L.; Viel, L.; Weese, J.S. A multidisciplinary approach to reduce and refine antimicrobial drugs use for diarrhoea in dairy calves. Vet. J. 2021, 274, 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, D.; James, D.; Marsden, N. Marginal gains: Olympic lessons in high performance for organisations. HR Bull. Res. Pract. 2012, 7, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hillegass, B.E.; Smith, D.M.; Phillips, S.L. Changing managed care to care management: Innovations in nursing practice. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2002, 26, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodner, D.L.; Spreeuwenberg, C. Integrated care: Meaning, logic, applications, and implications—A discussion paper. Int. J. Integr. Care 2002, 2, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auschra, C. Barriers to the integration of care in inter-organisational settings: A literature review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyatt, A.Z. Service Provision in the Animal Health Sector. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harper Adams University, Newport, UK, 2017. Available online: https://hau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/17296 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Loomans, J.B.A.; Waaijer, P.G.; Maree, J.T.M.; van Weeren, P.R.; Barneveld, A. Quality of equine veterinary care. Part 2: Client satisfaction in equine top sports medicine in The Netherlands. Equine Vet. Educ. 2009, 21, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatt, A.Z.; Walley, K.; Wright, G.H.; Bleach, E.C.L. Co-Produced Care in Veterinary Services: A Qualitative Study of UK Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, F.J.; Doherty, M.L. Production diseases of the transition cow. Vet. J. 2008, 176, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, F.J.; O’Grady, L.; Rice, D.A.; Doherty, M.L. A herd health approach to dairy cow nutrition and production disease of the transition cow. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2006, 96, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.L. The role of veterinarians in equestrian sport: A comparative review of ethical issues surrounding human and equine sports medicine. Vet. J. 2013, 197, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.; De Brún, A.; Birken, S.A.; Davies, C.; McAuliffe, E. The micropolitics of implementation; a qualitative study exploring the impact of power, authority, and influence when implementing change in healthcare teams. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muca, E.; Cavallini, D.; Raspa, F.; Bordin, C.; Bergero, D.; Valle, E. Integrating new learning methods into equine nutrition classrooms: The importance of students’ perceptions. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 126, 104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muca, E.; Buonaiuto, G.; Lamanna, M.; Silvestrelli, S.; Ghiaccio, F.; Federiconi, A.; De Matos Vettori, J.; Colleluori, R.; Fusaro, I.; Raspa, F.; et al. Reaching a Wider Audience: Instagram’s Role in Dairy Cow Nutrition Education and Engagement. Animals 2023, 13, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Qualified Saddle Fitters (SMSQSF) | Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters |

|---|---|

| Master Saddle Fitter (SMSMSF) | SMS master saddle fitters will hold the Society saddle fitting qualification, will have a minimum of seven years’ experience and will either be a member in their own right or will be employed by a member. They will also either be a Master Saddler or hold the Society’s Flocking & Flocking Adjustment qualification and will have provided references from both customers and fellow saddle fitters. |

| Master Saddler (SMSMS) | Master Saddlers are trained, skilled and qualified in their own right to make and repair saddlery. They will have a minimum of 7 years’ experience in the trade. Master Saddlers do not necessarily have retail premises. |

| Musculoskeletal practitioner | Musculoskeletal practitioners include animal/veterinary physiotherapists, animal chiropractors, animal osteopaths and animal massage therapists. |

| Multidisciplinary team | Professionals from different disciplines working in collaboration for a common goal |

| Interview Topics | Areas Explored |

|---|---|

| Client Base | The nature of the participant’s business, client base, geographical area covered and client type |

| Understanding of ‘interdisciplinary’ and ‘multidisciplinary’ | The nature of interdisciplinary and MDT practice for the participant, the frequency and nature of interactions with others, the process itself, channels of communication with others |

| Experiences of working with others | Client expectations of the MDT, advantages and disadvantages of working within a MDT, using specific examples |

| Future Development | The value of MDT working to the profession, barriers and possible improvements |

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Effective Communication | Quality and respectful communications are pivotal to successful inter-disciplinary interactions |

| 2. Multidisciplinary Expectations | Potential for successful team-based approaches |

| 3. Horse Welfare | Welfare as the centre-point of all professional interventions |

| 4. Professionalism | Recognition and appreciation of professional recognition and boundaries, and the association with robust decision-making skills |

| 5. Relationships | Value of positive and transparent client: professional and professional: professional relationships |

| 6. Working Together | Benefits and challenges associated with a collaborative approach |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nankervis, K.; MacKechnie-Guire, R.; Maddock, C.; Pyatt, A. Experiences of Interdisciplinary Working from the Perspective of the Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters. Animals 2024, 14, 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040559

Nankervis K, MacKechnie-Guire R, Maddock C, Pyatt A. Experiences of Interdisciplinary Working from the Perspective of the Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters. Animals. 2024; 14(4):559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040559

Chicago/Turabian StyleNankervis, Kathryn, Russell MacKechnie-Guire, Christy Maddock, and Alison Pyatt. 2024. "Experiences of Interdisciplinary Working from the Perspective of the Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters" Animals 14, no. 4: 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040559

APA StyleNankervis, K., MacKechnie-Guire, R., Maddock, C., & Pyatt, A. (2024). Experiences of Interdisciplinary Working from the Perspective of the Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters. Animals, 14(4), 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040559