Contributions of Multilevel Family Factors to Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Factor at System Level Associated with Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Children with ODD

1.2. Factor at Dyadic Level Associated with Emotion and Behavioral Problems in Children with ODD

1.3. Factor at Individual Level Associated with Emotion and Behavioral Problems in Children with ODD

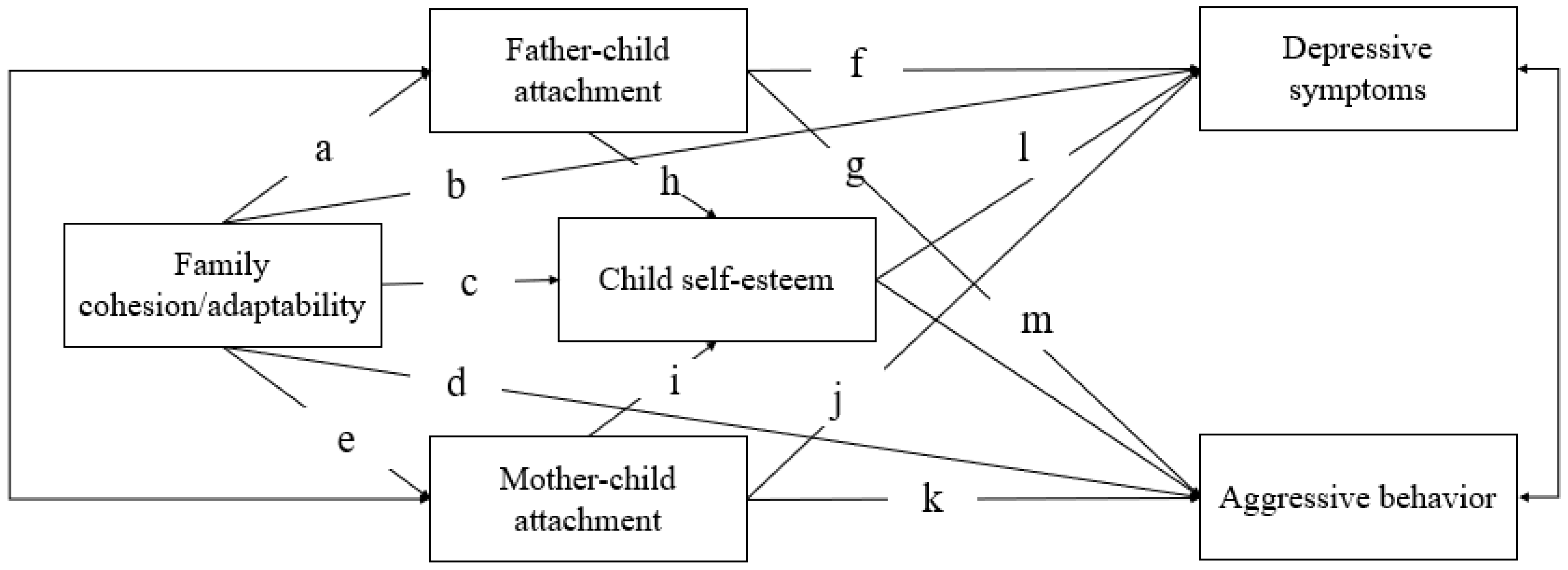

1.4. Interplay among Factors at Three Level

1.5. Influence of Chinese Culture

1.6. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. ODD Symptoms

2.3.2. Family Cohesion/Adaptability (Parent Reported)

2.3.3. Parent–Child Attachment (Child Reported)

2.3.4. Child Self-Esteem (Child Reported)

2.3.5. Children Depressive Symptoms (Child Reported)

2.3.6. Aggressive Behavior (Teacher Reported)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics among All Variables of Interest

3.2. The Mediating Roles of Mother–Child and Father–Child Attachment and Child Self-Esteem

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Prospects

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta, L.; Penelo, E.; Navarro, J.B.; de la Osa, N.; Trepat, E. Co-developmental trajectories of defiant/headstrong, irritability, and prosocial emotions from preschool age to early adolescence. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 53, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Kazdin, A.E.; Hiripi, E.; Kessler, R.C. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.E.; Lee, C.A.; Martel, M.M.; Axelrad, M.E. ODD symptom network during preschool. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 45, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bernhard, A.; Mayer, J.S.; Fann, N.; Freitag, C.M. Cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in ADHD compared to conduct disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wu, M.; Jiang, S.; Zou, H. Longitudinal links among parent-child attachment, emotion parenting, and problem behaviors of preadolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Feng, X. Trajectories of mother-child and father-child relationships across middle childhood and associations with depressive symptoms. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Lin, X.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Du, H.; Qin, S.; Fang, X. Longitudinal associations between oppositional defiant symptoms and interpersonal relationships among Chinese children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 46, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, W.L.; Kawabata, Y.; Gau, S.S.F. Social adjustment among Taiwanese children with symptoms of ADHD, ODD, and ADHD comorbid with ODD. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Li, L.; Gu, D.; Tan, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X. Parental depression and conduct problems among Chinese migrant children with oppositional defiant disorder symptoms: Testing moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, J.V.; Gouze, K.R.; Hopkins, J.; Bryant, F.B.; Lebailly, S.A. A multi-domain model of risk factors for ODD symptoms in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2012, 40, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; He, T.; Melissa, A.H.; Chi, P.; Hinshaw, S. A Review of Multiple Family Factors Associated with Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.M.; Walter, G.; Plapp, J.M.; Denshire, E. Family environment in attention deficit hyperactivity, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 34, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.H. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, D.R.; Ngai, S.W.; Larson, J.H.; Hafen, M. The influence of family functioning and parent-adolescent acculturation on North American Chinese adolescent outcomes. Fam. Relat. 2005, 54, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.W.; Ryan, C.E.; Keitner, G.I.; Bishop, D.S.; Epstein, N.B. The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Atzaba-Poria, N.; Pike, A. Mother- and father-child mutuality in Anglo and Indian British families: A link with lower externalizing behavior problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rinaldi, C.M.; Howe, N. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branstetter, S.A.; Fuman, W. Buffering effect of parental monitoring knowledge and parent-adolescent relationships on consequences of adolescent substance use. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruit, A.; Goos, L.; Weenink, N.; Rodenburg, R.; Niemeyer, H.; Stams, G.J.; Colonnesi, C. The relation between attachment and depression in children and adolescents: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. Attachments beyond infancy. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Ran, G.; Teng, Z. Different effects of paternal and maternal attachment on psychological health among Chinese secondary school students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2998–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess, G.J.; Grossmann, K.E.; Sroufe, L.A. Effects of Infant Attachment to Mother and Father on Quality of Adaptation in Preschool: From Dyadic to Individual Organisation of Self. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1992, 15, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.E.; Boyd-Soisson, E.; Jacobvitz, D.B.; Hazen, N.L. Dyadic and Triadic Family Interactions as Simultaneous Predictors of Children’s Externalizing Behaviors. Fam. Relat. 2017, 66, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, C.; Ritchie, S. Attachment organizations in children with difficult life circumstances. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999, 11, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunkenheimer, E.; Hamby, C.M.; Lobo, F.M.; Cole, P.M.; Olson, S.L. The role of dynamic, dyadic parent-child processes in parental socialization of emotion. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.B.; McHale, S.M.; Crouter, A.C. Parent-child shared time from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 2089–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Branje, S.J.; Hale, W.W.; Frijns, T.; Meeus, W.H. Longitudinal associations between perceived parent-child relationship quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, J.S.; Smith, S.; Bostick, S.; Grant, K.E. Mediating effects of parent-child relationships and body image in the prediction of internalizing symptoms in urban youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botero, J.C.R.; Medina, C.M.A.; Rizzo, A.A.; Aristizabal, A.C.G.; Zuluaga, E.H. Relationship between social cognition and executive functions in children with oppositional defiant disorder. Rev. Iberoam. De Diagn. Y Eval. Psicol. 2016, 2, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kearney, R.; Salmon, K.; Liwag, M.; Fortune, C.; Dawel, A. Emotional abilities in children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD): Impairments in perspective–taking and understanding mixed emotions are associated with high callous–unemotional traits. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Metalsky, G.I., Jr.; Joiner, T.E.; Hardin, T.S.; Abramson, L.Y. Depressive reactions to failure in a naturalistic setting: A test of the hopelessness and self-esteem theories of depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1993, 102, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965; Volume 11, pp. 326–343. [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwis, F.H.; Koot, H.M.; Creemers, D.H.; Van Lier, P.A. Implicit and explicit self-esteem discrepancies, victimization and the development of late childhood internalizing problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 43, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Fang, X. How paternal and maternal psychological control affect on internalizing and externalizing problems of children with ODD symptoms. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2014, 30, 635–645. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, D.; Stattin, H. Person-Context Interaction Theories; Handbook of Child Psychology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 685–759. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Li, L.; Heath, M.A.; Chi, P.; Xu, S.; Fang, X. Multiple levels of family factors and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms among Chinese children. Family Process 2018, 57, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.; Lavigne, J.V.; Gouze, K.R.; LeBailly, S.A.; Bryant, F.B. Multi-domain models of risk factors for depression and anxiety symptoms in preschoolers: Evidence for common and specific factors. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, L. The effect of family functioning on anger: The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Shanxi Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Chin.) 2018, 41, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Ai, H. Self-esteem mediates the effect of the parent-adolescent relationship on depression. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 21, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cicchetti, D. A longitudinal study of child maltreatment, mother-child relationship quality and maladjustment: The role of self-esteem and social competence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.W.K.; Tsang, E.Y.H.; Chen, H.-F. Parental socialization and development of Chinese youths: A multivariate and comparative approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, L.; Schwartz, D.; Dodge, K.A.; McBride-Chang, C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fan, M. Effects of the “one-child” policy and the number of children in families on the mental health of children in China. Rev. De Cercet. Şi Interv. Soc. 2016, 52, 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Research on the sexual division of labor. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed. Chin.) 2016, 5, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, S.; Way, N.; Yoshikawa, H.; Zhang, G.; Deng, H.; Cao, R.; Chen, H.; Li, D. Autonomy- and connectedness-oriented behaviors of toddlers and mothers at different historical times in urban china. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Fathers’ Involvement in Chinese Societies: Increasing Presence, Uneven Progress. Child Dev. Perspect. 2020, 14, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhu, S.; Bi, C. The development of self-esteem and the role of agency and communion: A longitudinal study among Chinese. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the PRC. China Family Development Report 2015; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.Y.; Luo, X.R.; Wei, Z.; Guan, B.Q. Parenting styles, parenting locus of control and family function of children with oppositional defiant disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 19, 209–211. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.C.; Zeng, R. The trait of attachment and the effect of attachment on social adjustment of middle school students: Parents intimacy as a moderator. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2010, 26, 577–583. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Ding, W.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Xie, R. The longitudinal relationship between filial piety and prosocial behavior of children: The chain mediating effect of self-esteem and peer attachment. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendrich, M.; Weissman, M.M.; Warner, V. Screening for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: Validating the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for children. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 131, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Power, T.G. Childhood depressive symptoms during the transition to primary school in Hong Kong: Comparison of child and maternal reports. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 100, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W.; Profilet, S.M. The child behavior scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Lv, Y.; Li, X.; Fang, X.; Zhao, G.; Lin, X.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Stanton, B. School performance and school behaviour of children affected by acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in China. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2009, 4, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus: Statistical Analyses with Latent Variables. User’s Guide, 3; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dekovic, M.; Janssens, J.M.A.M.; As, N.M.C. Family predictors of antisocial behavior in adolescence. Family Process 2004, 42, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Wu, X.C.; Zou, S.Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, B.B. The association between parental involvement and adolescent’s prosocial behavior: The mediating role of parent-child attachment. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2018, 34, 417–425. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.L.; McBride, B.A.; Shin, N.; Bost, K.K. Parenting predictors of father-child attachment security: Interactive effects of father involvement and fathering quality. Fathering 2007, 5, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.L. An examination of three models of the relationships between parental attachments and adolescents’ social functioning and depressive symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Tambor, E.S.; Terdal, S.K.; Downs, D.L. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 68, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.L.; Mangelsdorf, S.C.; Neff, C.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Frosch, C.A. Young children’s self-concepts: Associations with child temperament, mothers’ and fathers’ parenting, and triadic family interaction. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2009, 55, 184–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xing, X.; Zhao, J. Intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment in china: The moderating role of marital satisfaction and gender. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Children’s gender | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Children’s age | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. Paternal age | 0.18 ** | 0.17 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. Maternal age | 0.15 * | 0.23 ** | 0.80 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. Paternal education | 0.06 | −0.25 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.19 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. Maternal education | −0.06 | −0.28 ** | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.75 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. Monthly income | 0.23 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.48 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 8. Family cohesion/adaptability | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.23 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.17 * | 1 | |||||

| 9. Father–child attachment | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.17 * | 0.12 | 0.22 ** | 1 | ||||

| 10. Mother–child attachment | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.21 ** | 0.10 | 0.27 ** | 0.70 ** | 1 | |||

| 11. Child self-esteem | −0.20 ** | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.21 ** | 0.01 | 0.28 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.48 ** | 1 | ||

| 12. Child depression | 0.15 * | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.24 ** | −0.58 ** | −0.64 ** | −0.58 ** | 1 | |

| 13. Aggressive behavior | 0.34 ** | 0.04 | 0.28 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.13 * | 0.25 ** | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.20 ** | 0.21 ** | 1 |

| Mean | 9.60 | 38.43 | 36.66 | 3.87 | 3.74 | 2.79 | 121.06 | 23.88 | 25.74 | 30.53 | 36.06 | 17.90 | |

| SD | 1.57 | 5.16 | 4.29 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 1.03 | 17.19 | 11.80 | 12.24 | 6.16 | 10.40 | 7.77 |

| Path | Β | SE | p | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child depression as outcome | ||||

| family cohesion/adaptability → child depression | −0.007 | 0.03 | 0.91 | [−0.06, 0.07] |

| father–child attachment → child depression | −0.25 | 0.10 | 0.046 | [−0.45, −0.03] |

| mother–child attachment → child depression | −0.36 | 0.11 | 0.009 | [−0.51, −0.07] |

| child self-esteem → child depression | −0.31 | 0.14 | <0.000 | [−0.82, −0.23] |

| Child aggression as outcome | ||||

| family cohesion/adaptability → child aggression | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.64 | [−0.08, 0.05] |

| father–child attachment → child aggression | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.21 | [−0.06, 0.24] |

| mother–child attachment → child aggression | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.55 | [−0.11, 0.20] |

| child self-esteem → child aggression | −0.13 | 0.10 | 0.001 | [−0.60, −0.16] |

| Path | β | SE | p | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child depression as outcome | ||||

| family cohesion/adaptability → mother–child attachment → child depression | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | [−0.17, −0.01] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → father–child attachment → child depression | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.11 | [−0.11, 0.01] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → child self-esteem → child depression | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.15 | [−0.10, 0.01] |

| mother–child attachment → child self-esteem → child depression | −0.12 | 0.04 | 0.002 | [−0.20, −0.05] |

| father–child attachment → child self-esteem → child depression | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.45 | [−0.07, 0.03] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → mother–child attachment → child self-esteem → child depression | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.06, −0.01] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → father–child attachment → child self-esteem → child depression | −0.004 | 0.01 | 0.54 | [−0.02, 0.01] |

| Child aggression as outcome | ||||

| family cohesion/adaptability → mother–child attachment → child aggression | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.45 | [−0.04, 0.09] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → father–child attachment → child aggression | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.35 | [−0.02, 0.07] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → child self-esteem → child aggression | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | [−0.10, 0.01] |

| mother–child attachment → child self-esteem → child aggression | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.003 | [−0.22, −0.05] |

| father–child attachment → child self-esteem → child aggression | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.46 | [−0.07, 0.03] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → mother–child attachment → child self-esteem → child aggression | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.07, −0.01] |

| family cohesion/adaptability → father–child attachment → child self-esteem → child aggression | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.54 | [−0.02, 0.01] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, T.; Meza, J.; Ding, W.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Zhou, Q.; Akram, U.; Lin, X. Contributions of Multilevel Family Factors to Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder in China. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020113

He T, Meza J, Ding W, Hinshaw SP, Zhou Q, Akram U, Lin X. Contributions of Multilevel Family Factors to Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(2):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020113

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Ting, Jocelyn Meza, Wan Ding, Stephen P. Hinshaw, Qing Zhou, Umair Akram, and Xiuyun Lin. 2023. "Contributions of Multilevel Family Factors to Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder in China" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 2: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020113

APA StyleHe, T., Meza, J., Ding, W., Hinshaw, S. P., Zhou, Q., Akram, U., & Lin, X. (2023). Contributions of Multilevel Family Factors to Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder in China. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020113