Integrating Guilt and Shame into the Self-Concept: The Influence of Future Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Distinguishing between Guilt and Shame

1.2. Self-Conscious Emotions and Integration into the Self-Concept

1.3. Future Opportunity

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants and Design

2.1.2. Procedure and Materials

Try to recall an outcome or event from your past that made you feel ashamed. The event outcome that you recall should be one that you could potentially improve upon in the future. In other words, the event outcome that you choose to recall should be one that could possibly happen to you again in the future. For example, you may have experienced shame in the past if you performed poorly on a presentation in front of your classmates or colleagues and you expect that you will be giving similar presentations in the future, or if you hurt the feelings of a friend whom you expect to see again.

Try to recall an outcome or event from your past that made you feel ashamed. The event outcome that you recall should be one that you cannot improve upon in the future. In other words, the event outcome that you choose to recall should be one that will probably not happen to you again in the future. For example, you may have experienced shame in the past if you performed poorly on a presentation in front of your classmates or colleagues and you do not expect to be giving similar presentations in the future, or if you hurt the feelings of a friend whom you do not expect to see again.

Try to recall an outcome or event from your past that made you feel guilty. The event outcome that you recall should be one that you could potentially improve upon in the future. In other words, the event outcome that you choose to recall should be one that could possibly happen to you again in the future. For example, you may have experienced guilt in the past if you neglected your duties as a member of a team that was working on an ongoing project, or if you lied to a friend whom you expect to see again.

Try to recall an outcome or event from your past that made you feel guilty. The event outcome that you recall should be one that you cannot improve upon in the future. In other words, the event outcome that you choose to recall should be one that will probably not happen to you again in the future. For example, you may have experienced guilt in the past if you neglected your duties as a member of a team that was working on a one-time project, or if you lied to a friend whom you do not expect to see again.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Manipulation Check

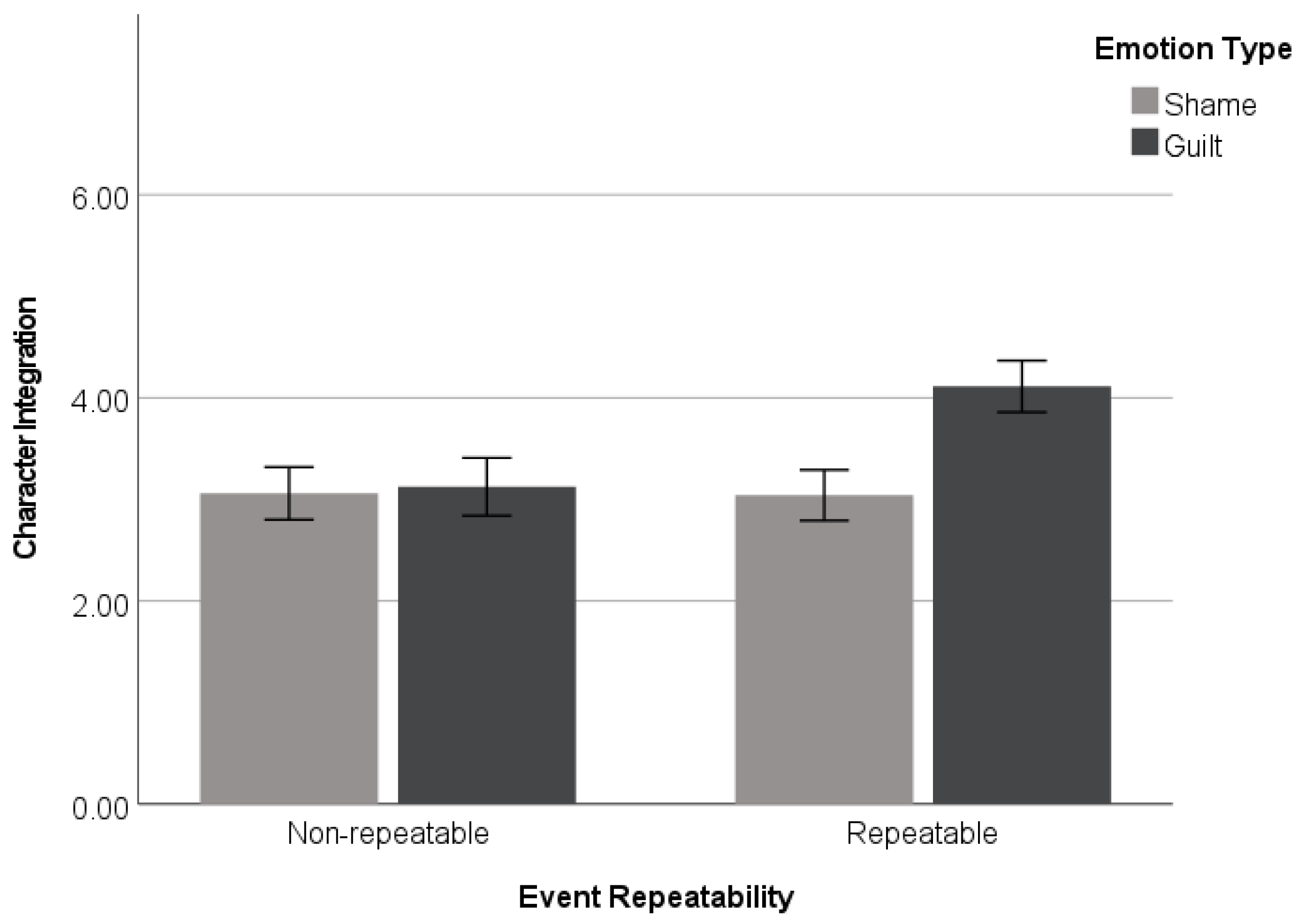

2.2.2. Character Integration

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants and Design

3.1.2. Procedure and Materials

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Check

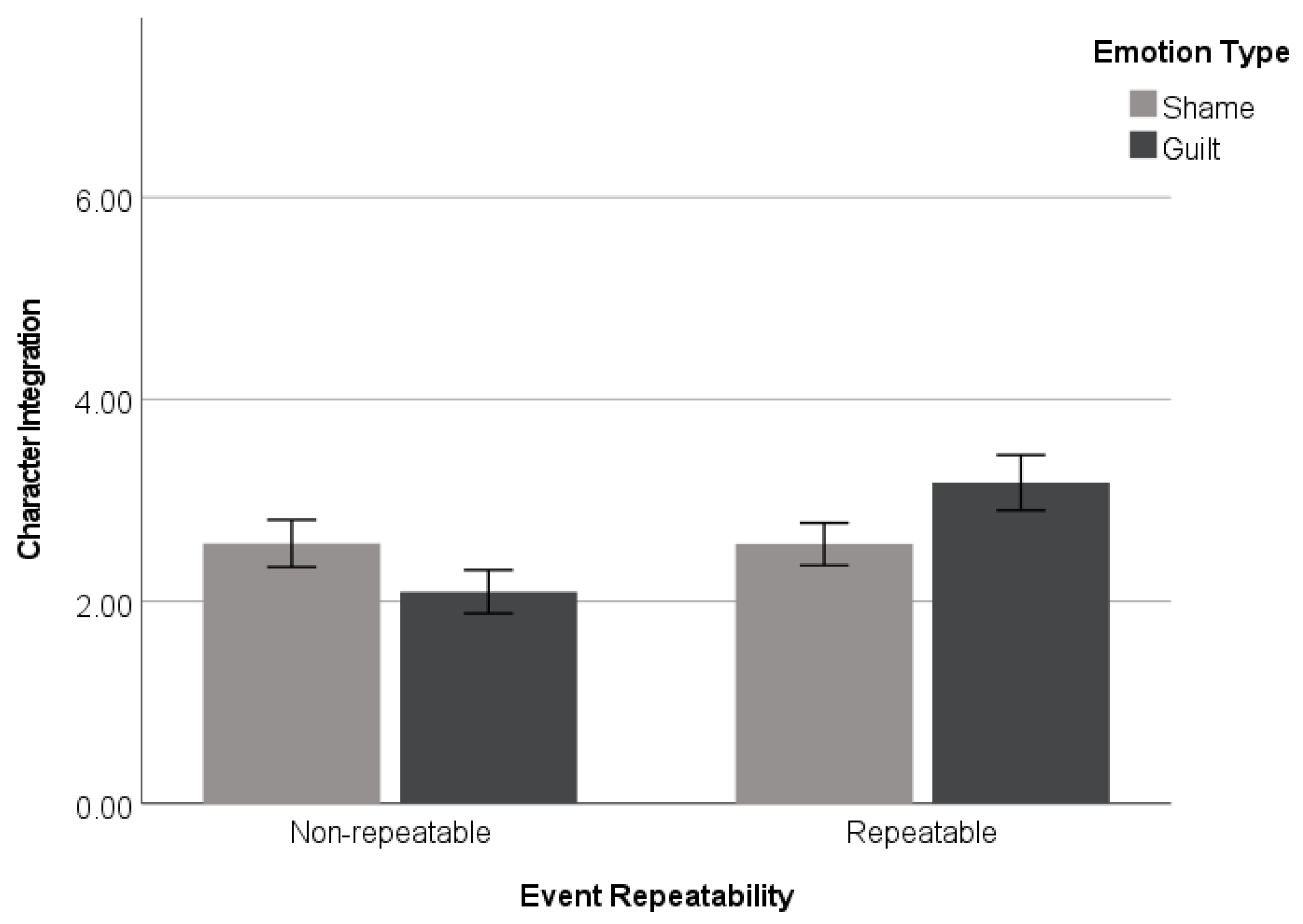

3.2.2. Character Integration

3.2.3. Event Integration

3.2.4. Future Coping Confidence

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLean, K.C.; Pratt, M.W. Life’s little (and big) lessons: Identity statuses and meaning-making in the turning point narratives of emerging adults. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.A. Narrative identity and meaning-making across the adult lifespan: An introduction. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, K.D.; Proulx, T.; Lindberg, M.J. (Eds.) The Psychology of Meaning; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eskreis-Winkler, L.; Fishbach, A. Not learning from failure—The greatest failure of all. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M. How the self became involved in affective experience: Three sources of self-reflective emotions. In The Self-Conscious Emotions: Theory and Research; Tracy, J., Robins, R., Tangney, J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, S.; Janoff-Bulman, R. The “shoulds” and “should nots” of moral emotions: A self-regulatory perspective on shame and guilt. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.L. Shame and Guilt; Guilford Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P.; Tracy, J.L. Self-conscious emotions. In Handbook of Self and Identity, 2nd ed.; Leary, M., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 446–478. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P.; Niedenthal, P.M.; Covert, M.V.; Barlow, D.H. Are shame and guilt related to distinct self-discrepancies? A test of Higgins’s (1987) hypotheses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, H.B. Shame and Guilt in Neurosis; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Stillwell, A.M.; Heatherton, T.F. Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keltner, D.; Buswell, B.N. Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cogn. Emot. 1996, 10, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedenthal, P.M.; Tangney, J.P.; Gavanski, I. “If only I weren’t” versus “if only I hadn’t”: Distinguishing shame and guilt in counterfactual thinking. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchaki, M.; Oveis, C.; Gino, F. Guilt enhances the sense of control and drives risky judgments. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, P.; Peetz, J. When does feeling moral actually make you a better person? Conceptual abstraction moderates whether past moral deeds motivate consistency or compensatory behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Duhachek, A.; Agrawal, N. Emotions shape decisions through construal level: The case of guilt and shame. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leith, K.P.; Baumeister, R.F. Empathy, shame, guilt, and narratives of interpersonal conflicts: Guilt-prone people are better at perspective taking. J. Personal. 1998, 66, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.R.; Wolf, S.T.; Panter, A.T.; Insko, C.A. Introducing the GASP scale: A new measure of guilt and shame proneness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 947–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.L.; Wagner, P.E.; Gramzow, R.H. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect–3 (TOSCA-3); George Mason University: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hosser, D.; Windzio, M.; Greve, W. Guilt and shame as predictors of recidivism: A longitudinal study with young prisoners. Crim. Justice Behav. 2008, 35, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Stuewig, J.; Martinez, A.G. Two faces of shame: The roles of shame and guilt in predicting recidivism. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. Feeling one thing and doing another: How expressions of guilt and shame influence hypocrisy judgment. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. Consideration of future consequences affects the perception and interpretation of self-conscious emotions. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. A self-determination theory approach to psychotherapy: The motivational basis for effective change. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. Personal needs personal relationships. In Handbook of Personal Relationships; Duck, S., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1988; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, N.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Motivational determinants of integrating positive and negative past identities. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M. Experiments in the heuristic use of past proof experience. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: London, UK, 1996; Volume 1104, pp. 523–537. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P. What do we know when we know a person? J. Personal. 1995, 63, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pals, J.L. The narrative identity processing of difficult life experiences: Pathways of personality development and positive self-transformation in adulthood. J. Personal. 2006, 74, 1079–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.E.; Ross, M. From chump to champ: People’s appraisals of their earlier and present identities. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J.P.; Wagner, P.; Fletcher, C.; Gramzow, R. Shamed into anger? The relation of shame and guilt to anger and selfreported aggression. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vess, M.; Schlegel, R.J.; Hicks, J.A.; Arndt, J. Guilty, but not ashamed: “True” self-conceptions influence affective responses to personal shortcomings. J. Personal. 2014, 82, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, R.J.; Hicks, J.A. The true self and psychological health: Emerging evidence and future directions. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. The impact of self-affirmation on health cognition, health behaviour and other health-related responses: A narrative review. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2009, 3, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, K.D.; Beike, D.R. Regret, consistency, and choice: An opportunity X mitigation framework. In Cognitive Consistency: A Fundamental Principle in Social Cognition; Gawronski, B., Strack, F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Roese, N.J.; Summerville, A. What we regret most… and why. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, T.R.; Panter, A.T.; Turan, N.; Morse, L.; Kim, Y. Moral character in the workplace. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beike, D.R.; Markman, K.D.; Karadogan, F. What we regret most are lost opportunities: A theory of regret intensity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, K.D.; Gavanski, I.; Sherman, S.J.; McMullen, M.N. The mental simulation of better and worse possible worlds. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 29, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, R.B.; Prentice-Dunn, S. Effects of coping information and value affirmation on responses to a perceived health threat. Health Commun. 2005, 17, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; DeWall, C.N.; Zhang, L. How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H.; Kuipers, P.; ter Schure, E. Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, M.; Sznycer, D.; Durkee, P. Are self-conscious emotions about the self? Testing competing theories of shame and guilt across two disparate cultures. Emotion 2024. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Nurius, P. Possible selves. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Reynolds, J.; Lewis, M.; Patten, A.; Bowman, P.J. When bad things turn good and good things turn bad: Sequences of redemption and contamination in life narrative, and their relation to psychosocial adaptation in midlife adults and in students. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Strain, L.M. Content structure of the self. In The Self in Social Psychology; Sedikides, C., Spencer, S., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P.; McLean, K.C. Narrative identity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickel, B.; Kushlev, K.; Savalei, V.; Matta, S.; Schmader, T. Shame and the motivation to change the self. Emotion 2014, 14, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H. Integrating Guilt and Shame into the Self-Concept: The Influence of Future Opportunities. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060472

Choi H. Integrating Guilt and Shame into the Self-Concept: The Influence of Future Opportunities. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060472

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hyeman. 2024. "Integrating Guilt and Shame into the Self-Concept: The Influence of Future Opportunities" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060472

APA StyleChoi, H. (2024). Integrating Guilt and Shame into the Self-Concept: The Influence of Future Opportunities. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060472