Assessing the Impact of Recommendation Novelty on Older Consumers: Older Does Not Always Mean the Avoidance of Innovative Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Recommendation Novelty

2.2. Aging and Innovative Product Adoption

2.3. Social Influence Theory

2.4. Cognitive Age

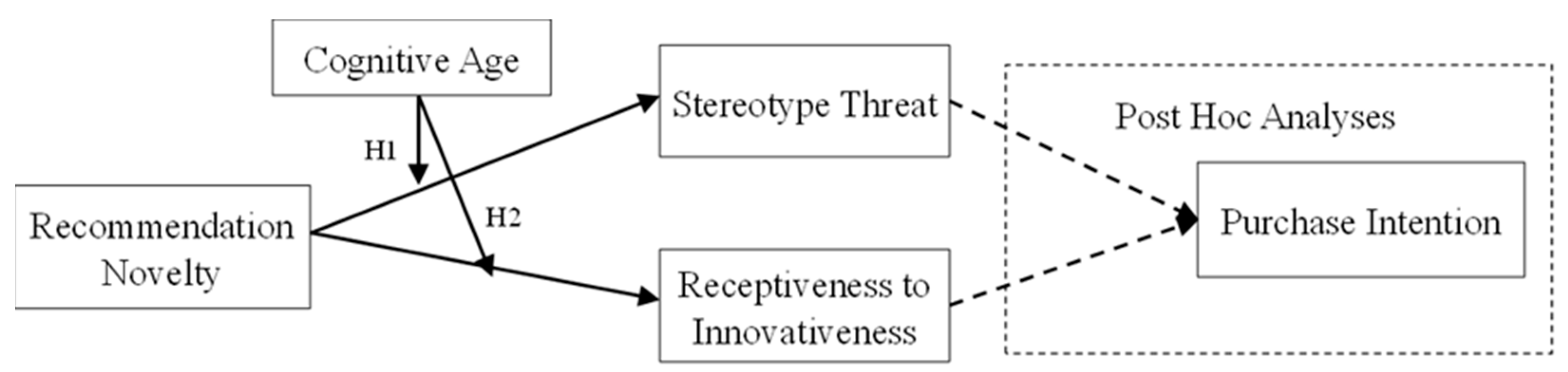

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Stereotypes Threaten Perception

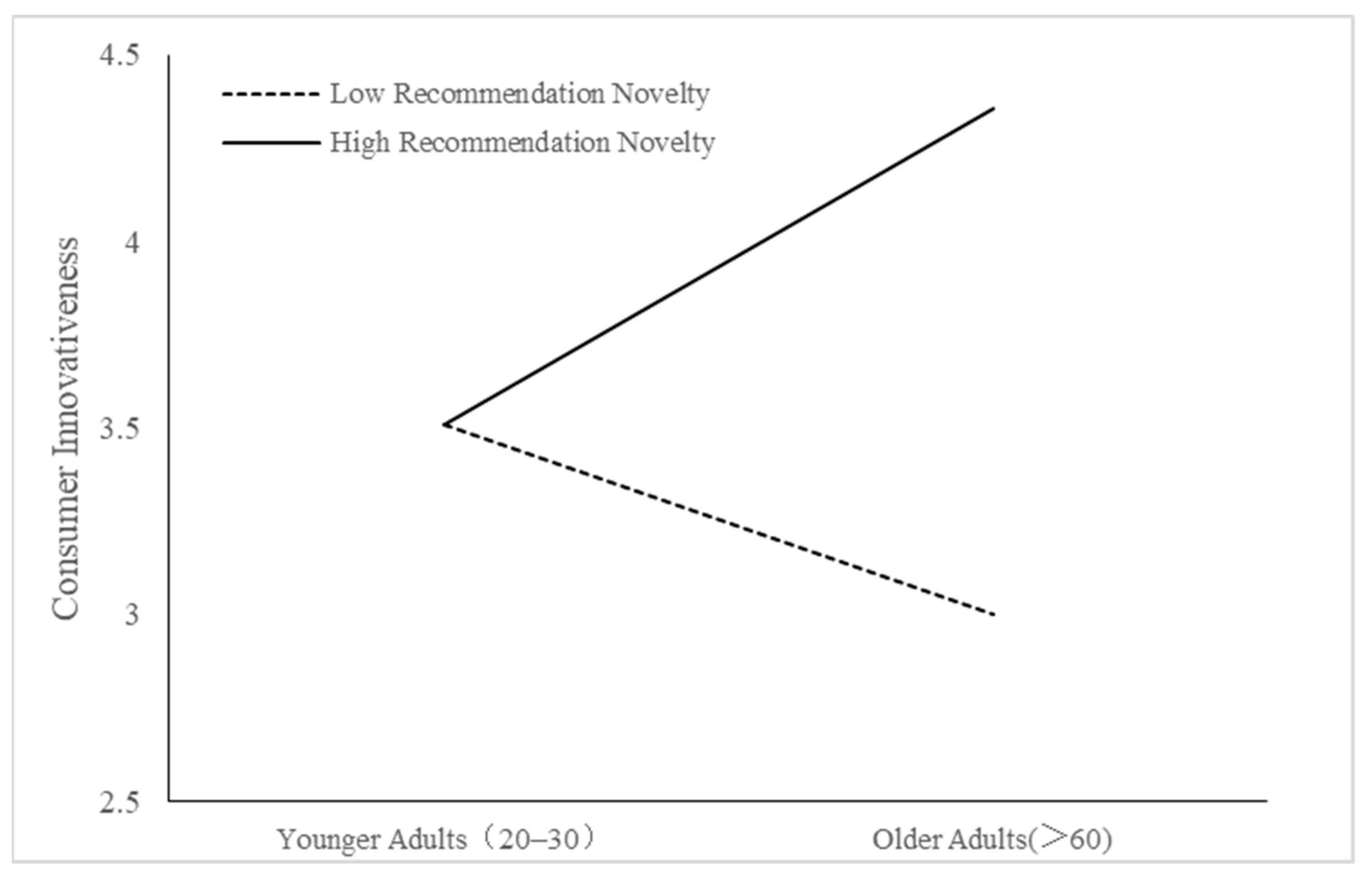

3.2. Consumer Receptiveness to Innovativeness

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Measurements of Variables

4.3. Sample

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Manipulation Check

5.2. Construct Validation

5.3. Tests of the Moderation Hypotheses

5.4. Post Hoc Analyses

6. Contributions, Limitations, and Future Research

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Contributions

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Low Recommendation Novelty and High Recommendation Novelty

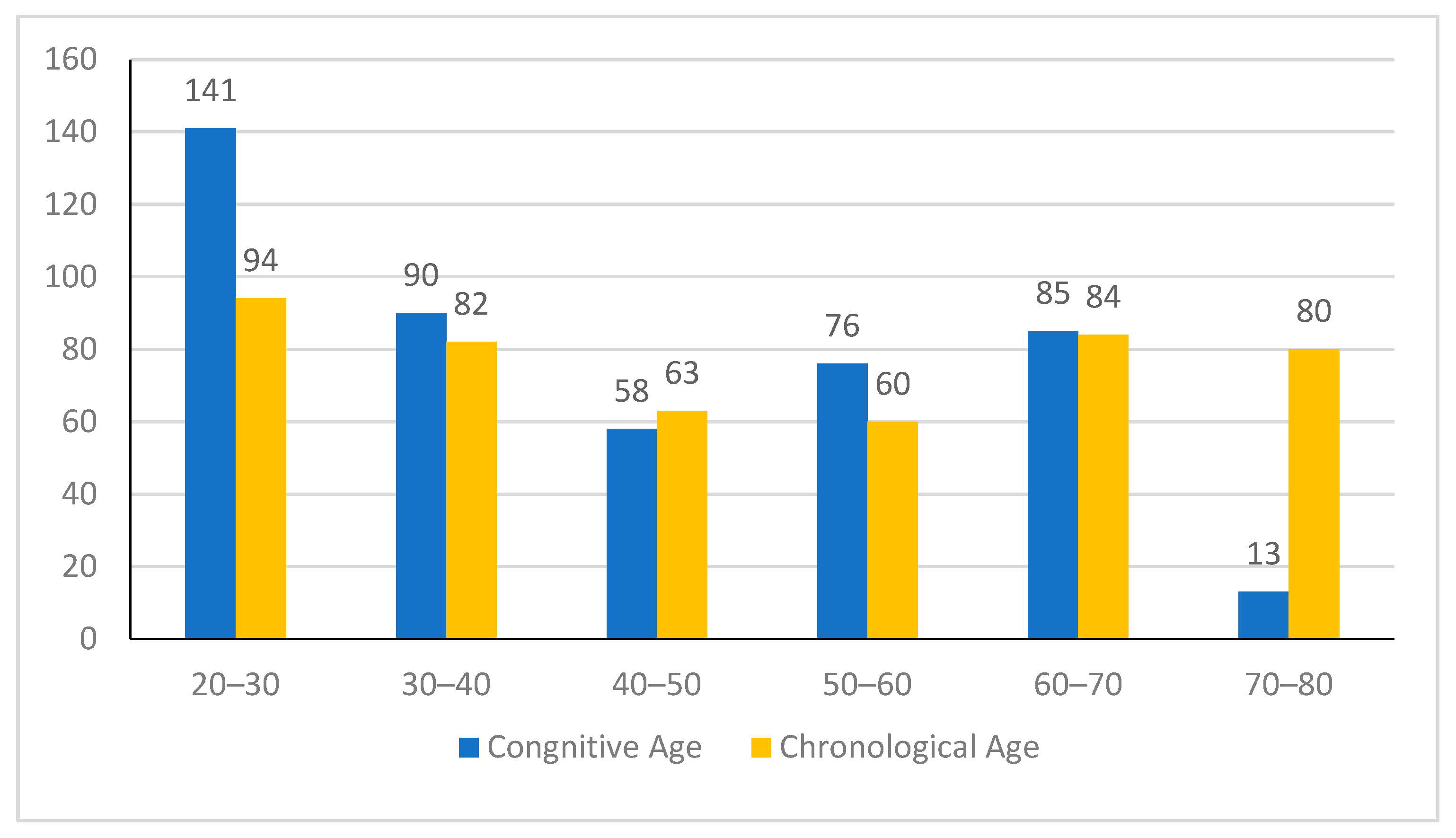

Appendix B. Group Comparisons between Cognitive Versus Chronological Age

| Cognitive Age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–30 | 30–40 | 40–50 | 50–60 | 60–70 | 70–80 | Total | |

| 20–30 | 84 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 94 |

| 30–40 | 44 | 32 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 82 |

| 40–50 | 8 | 39 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 63 |

| 50–60 | 5 | 9 | 28 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| 60–70 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 48 | 20 | 3 | 84 |

| 70–80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 65 | 10 | 80 |

| Total | 141 | 90 | 58 | 76 | 85 | 13 | 463 |

References

- Ghasemaghaei, M.; Hassanein, K.; Benbasat, I. Assessing the design choices for online recommendation agents for older adults: Older does not always mean simpler information technology. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.; Mora, D.; Cirqueira, D.; Helfert, M.; Bezbradica, M.; Werth, D.; Weitzl, W.J.; Riedl, R.; Auinger, A. Enhancing brick-and-mortar store shopping experience with an augmented reality shopping assistant application using personalized recommendations and explainable artificial intelligence. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svrcek, M.; Kompan, M.; Bielikova, M. Towards understandable personalized recommendations: Hybrid explanations. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2019, 16, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimamy, S.; Gnoth, J. I want it my way! The effect of perceptions of personalization through augmented reality and online shopping on customer intentions to co-create value. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kant, V. Credibility score based multi-criteria recommender system. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 196, 105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, D.; Mao, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G. Recommender system application developments: A survey. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 74, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, N.C.; Zhang, R. “I will buy what my ‘friend’ recommends”: The effects of parasocial relationships, influencer credibility and self-esteem on purchase intentions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Guo, J.; Zhu, Y. A multi-aspect user-interest model based on sentiment analysis and uncertainty theory for recommender systems. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 20, 857–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karn, A.L.; Karna, R.K.; Kondamudi, B.R.; Bagale, G.; Pustokhin, D.A.; Pustokhina, I.V.; Sengan, S. Customer centric hybrid recommendation system for E-Commerce applications by integrating hybrid sentiment analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 279–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, L.; Sabic, A.; Zanker, M. Engagement in proactive recommendations: The role of recommendation accuracy, information privacy concerns and personality traits. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2020, 54, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, G.; Gunawardana, A. Evaluating Recommendation Systems. Recommender Systems Handbook; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y. Personalizing recommendation diversity based on user personality. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2018, 28, 237–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Yan, C.; Kou, H.; Qi, L. Diversified service recommendation with high accuracy and efficiency. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 204, 106169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Ma, H.S.; Chung, C.C.; Jian, Z.J. Unknown but interesting recommendation using social penetration. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 7249–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.B.E.M.; ter Hofstede, F.; Wedel, M. A Cross-National Investigation into the Individual and National Cultural Antecedents of Consumer Innovativeness. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Sharma, M. Social media adoption behaviour: Consumer innovativeness and participation intention. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, J.A.; Kunkel, S.R. Exploratory and problem-solving consumer behavior across the life span. J. Gerontol. 1991, 46, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.; Jo, S.H. The impact of age stereotype threats on older consumers’ intention to buy masstige brand products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, C.; Aaker, J.L.; Kamvar, S. How Happiness Affects Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettich, D.; Hattula, S.; Bornemann, T. Consumer Decision-Making of Older People: A 45-Year Review. Gerontologist 2018, 58, E349–E368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.W.; Yen, D.C. Online shopping drivers and barriers for older adults: Age and gender differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makita, M.; Mas-Bleda, A.; Stuart, E.; Thelwall, M. Ageing, old age and older adults: A social media analysis of dominant topics and discourses. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.A.; Swift, H.J.; Abrams, D. A review and meta-analysis of age-based stereotype threat: Negative stereotypes, not facts, do the damage. Psychol. Aging 2015, 30, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.; Jo, S.H.; Lee, E. Why do older consumers avoid innovative products and services? J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 35, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, J.; Marques, S.; Ramos, M.R.; Gerardo, F.; Cunha, C.L.; da Girenko, A.; Alexandersson, J.; Stree, B.; Lamanna, M.; Lorenzatto, M.; et al. Too old for technology? Stereotype threat and technology use by older adults. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, B.; O’Brien, L.T. The social psychology of stigma. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westberg, K.; Reid, M.; Kopanidis, F. Age identity, stereotypes and older consumers’ service experiences. J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 35, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 415–433. [Google Scholar]

- Szmigin, I.; Carrigan, M. The Older Consumer as Innovator Does Cognitive Age hold the Key? J. Mark. Manag. 2000, 16, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J. A Theory of Psychological Reactance; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Amatulli, C.; Peluso, A.M.; Guido, G.; Yoon, C. When feeling younger depends on others: The effects of social cues on older consumers. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.; Laurent, G.; Drolet, A.; Ebert, J.; Gutchess, A.; Lambert-pandraud, R.; Mullet, E.; Norton, M.I.; Peters, E. Decision making and brand choice by older consumers. Mark. Lett. 2008, 19, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, A.D. Memory for grocery prices in younger and older adults: The role of schematic support. Psychol. Aging 2005, 20, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.W.; Sternthal, B. Age Differences in Information Processing: A Perspective on the Aged Consumer. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, R.; Uncles, M.D.; Lomax, W. Hear nothing, do nothing: The role of word of mouth in the decision-making of older consumers. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T. Exploring and explaining older consumers’ behaviour in the boom of social media. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, J.; Sung, Y. The effect of gender stereotypes on artificial intelligence recommendations. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgonde, O.; Zhang, H.; Padmanabhan, B.; Limayem, M. Taming complexity in search matching: Two-sided recommender systems on digital platforms. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 44, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntoni, S.; Reczek, R.W.; Giesler, M.; Botti, S. Consumers and Artificial Intelligence: An Experiential Perspective. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brothers, A.; Gabrian, M.; Wahl, H.W.; Diehl, M. A New Multidimensional Questionnaire to Assess Awareness of Age-Related Change (AARC). Gerontologist 2019, 59, E141–E151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.J.; Tuzhilin, A. The long tail of recommender systems and how to leverage it. In Proceedings of the RecSys’08: 2008 ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 23–25 October 2008; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, P.; Hurley, N.J.; Vargas, S. Novelty and Diversity in Recommender Systems. In Recommender Systems Handbook, 2nd ed.; Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Séaghdha, D.Ó.; Quercia, D.; Jambor, T. Auralist: Introducing serendipity into music recommendation. In Proceedings of the WSDM 2012–5th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Seattle, WA, USA, 8–12 February 2012; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, T.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Sellis, T.; Xia, F. Community-diversified influence maximization in social networks. Inf. Syst. 2020, 92, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.; de Lange, A.; Jansen, P.; Dikkers, J. Older workers’ motivation to continue to work: Five meanings of age: A conceptual review. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 364–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutchess, A.H. Cognitive psychology neuroscience of aging. In The Aging Consumer: Perspectives from Psychology and Economics; Drolet, A., Schwarz, N., Yoon, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Boduroglu, A.; Yoon, C.; Luo, T.; Park, D.C. Age-related stereotypes: A comparison of American and Chinese cultures. Gerontology 2006, 52, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, P.; Sudbury, L.; Wright, G. Age, Perceived Risk and Satisfaction in Consumer Decision Making: A Review and Extension. J. Mark. Manag. 2006, 22, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosson, J.K.; Haymovitz, E.L.; Pinel, E.C. When saying and doing diverge: The effects of stereotype threat on self-reported versus non-verbal anxiety. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 40, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.W.; Motion, J.; Conroy, D. Anti-consumption and brand avoidance. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löckenhoff, C.E.; Carstensen, L.L. Socioemotionol selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1395–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert-Pandraud, R.; Laurent, G.; Lapersonne, E. Repeat purchasing of new automobiles by older consumers: Empirical evidence and interpretations. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Stephens, N. Testing the implied mediational role of cognitive age. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 1031–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Schindler, R.M. Echoes of the Dear Departed Past: Some Work in Progress On Nostalgia. Adv. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 330–335. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Schindler, R.M. Age, Sex, and Attitude toward the past as Predictors of Consumers’ Aesthetic Tastes for Cultural Products. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, S.S.; Baker, S.M. An Integrative Review of Material Possession Attachment. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2004, 2004, 1–35. Available online: https://www.uwyo.edu/mgtmkt/faculty-staff/faculty-pages/docs/baker/material%20possession%20attachment.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Cole, C.A.; Houston, M.J. Encoding and Media Effects on Consumer Learning Deficiencies in the Elderly. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaïd, M.; Kämmer, J.E.; Analytis, P.P.; Neth, H. Social influence and the collective dynamics of opinion formation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milgram, S. Behavioral Study of obedience. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnhart, M.; Peñaloza, L. Who are you calling old? Negotiating old age identity in the elderly consumption ensemble. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Kang, J.; Kim, M. The relationships among family and social interaction, loneliness, mall shopping motivation, and mall spending of older consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2005, 22, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N.L.; Baumeister, R.F.; Stillman, T.F.; Rawn, C.D.; Vohs, K.D. Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 37, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Dahl, D.W.; Manchanda, R.V. The influence of a mere social presence in a retail context. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhukya, R.; Paul, J. Social influence research in consumer behavior: What we learned and what we need to learn?—A hybrid systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J. Stereotype Threat and the Intellectual Test Performance of African Americans. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.M.; O’Brien, E.L.; Voss, P.; Kornadt, A.E.; Rothermund, K.; Fung, H.H.; Popham, L.E. Context influences on the relationship between views of aging and subjective age: The moderating role of culture and domain of functioning. Psychol. Aging 2017, 32, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Eastin, M.S. Birds of a feather flock together: Matched personality effects of product recommendation chatbots and users. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; van Weert, J.C.M.; Bol, N.; Loos, E.F.; Tytgat, K.M.A.J.; van de Ven, A.W.H.; Smets, E.M.A. Tailoring the Mode of Information Presentation: Effects on Younger and Older Adults’ Attention and Recall of Online Information. Hum. Commun. Res. 2017, 43, 102–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, E.; Schiffman, L.G.; Mathur, A. The influence of gender on the new-age elderly’s consumption orientation. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G.; Amatulli, C.; Peluso, A.M. Context Effects on Older Consumers’ Cognitive Age: The Role of Hedonic versus Utilitarian Goals. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, L.; Bunker, D. It’s all in the mind: Changing the way we think about age. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 55, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Gittenberger, E.; Schnedlitz, P. Cognitive age and grocery-store patronage by elderly shoppers. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, S. Relationships between felt age and perceived disability, satisfaction with recovery, self-efficacy beliefs and coping strategies. J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schau, H.J.; Gilly, M.C.; Wolfinbarger, M. Consumer identity renaissance: The resurgence of identity-inspired consumption in retirement. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouali, W.; Souiden, N. The role of cognitive age in explaining mobile banking resistance among elderly people. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Lui, C.S.M.; Hahn, J.; Moon, J.Y.; Kim, T.G. How old are you really? Cognitive age in technology acceptance. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F.; Hofmeister, A. Baby Boomers of different nations: Identifying horizontal international segments based on self-perceived age. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, R.J.; Lachman, M.E. Perceptions of aging in two cultures: Korean and American views on old age. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2006, 21, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; Daniel, M.; Kavé, G. Technology makes older adults feel older. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunan, D.; Di Domenico, M.L. Older Consumers, Digital Marketing, and Public Policy: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Public Policy Mark. 2019, 38, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter-Grühn, D.; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A.; Gerstorf, D.; Smith, J. Self-Perceptions of Aging Predict Mortality and Change With Approaching Death: 16-Year Longitudinal Results From the Berlin Aging Study. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraci, L.; De Forrest, R.; Hughes, M.; Saenz, G.; Tirso, R. The effect of cognitive testing and feedback on older adults’ subjective age. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2018, 25, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.; Freund, A.M. Still young at heart: Negative age-related information motivates distancing from same-aged people. Psychol. Aging 2012, 27, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert-Pandraud, R.; Laurent, G. Why do older consumers buy older brands? The role of attachment and declining innovativeness. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M.H.; Shippee, T.P. Age identity, gender, and perceptions of decline: Does feeling older lead to pessimistic dispositions about cognitive aging? J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2010, 65, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, M.P.; Price, L.L. Differentiating between cognitive and sensory innovativeness. Concepts, measurement, and implications. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 20, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L.; Swait, J. Psychological indicators of innovation adoption: Cross-classification based on need for cognition and need for change. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.R.; Cole, C.A. Age Differences in Information Processing: Understanding Deficits in Young and Elderly Consumers. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, B.; Schiffman, L.G. Cognitive age: A nonchronological age variable. Adv. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 602–606. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Cognitive-Age%3A-a-Nonchronological-Age-Variable-Barak-Schiffman/a02e442a78c2c676e0483ef68305911e252557b0 (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Baumgartner, H.; Steenkamp, J.B.E.M. Exploratory consumer buying behavior: Conceptualization and measurement. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, G. Consumer innovativeness–Concepts and measurements. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Jiang, Z.J.; Benbasat, I. Enticing and engaging consumers via online product presentations: The effects of restricted interaction design. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 31, 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker-Drob, E.M.; Salthouse, T.A. Adult Age Trends in the Relations Among Cognitive Abilities. Psychol. Aging 2008, 23, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Michael, K.; Chen, X. Factors affecting privacy disclosure on social network sites: An integrated model. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Cole, C.A. Aging Consumer Behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Haugtvedt, C.P., Herr, P.M., Kardes, F.R., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 247–270. [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, R.; Dickinson, A.; Goodman, J.; Syme, A.; Tiwari, L.; Newell, A.F. Early user involvement in the development of information technology-related products for older people. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2004, 3, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Punj, G. Consumer Decision Making on the Web: A Theoretical Analysis and Research Guidelines. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Zhou, L. The effect of image enhancement on influencer’s product recommendation effectiveness: The roles of perceived influencer authenticity and post type. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low Recommended Novelty | Highly Recommended Novelty | |

|---|---|---|

| Product Categories | Traditional mechanical door locks | Electronic smart door lock |

| Number of products | 8 | 8 |

| Constructs | Measures | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Age (COA) | COA1: I feel as though I am my age. | Barak and Schiffman (1981) [90] |

| COA2: I look as though I am my age. | ||

| COA3: I do most things as though I were my age. | ||

| COA4: My interests are mostly those of a person of my age | ||

| Stereotype Threat(STT) | STT1: Sometimes I feel that other people treat me as an older adult. | Bae, Jo, and Lee (2021) [24] |

| STT2: Some people feel that I am not good at work because of my age. | ||

| STT3: Some people feel that I have poor memory because of my age. | ||

| Receptiveness to Innovativeness (RTI) | RTI1: When I see a new or different product, I often want to see what it is like. | Baumgartner and Steenkamp (1996) [91]; Roehrich (2004) [92] |

| RTI2: When I see a new or different product for sale, I am not afraid of giving it a try. | ||

| RTI3: A new store or restaurant is something I would be eager to find out about. | ||

| RTI4: I am more interested in buying new than known products. | ||

| Purchase Intention (PUI) | PUI1: It is likely that I will consider buying the gate lock with recommendations if I need it. | Yi, Jiang, and Benbasat (2015) [93] |

| PUI2: I may purchase the recommended goods the next time I need them. | ||

| PUI3: Supposing a friend contacts me for advice on buying a gate lock, I would recommend the goods that are recommended online. |

| Constructs | STT | RTI | PUI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stereotype Threat (STT1) | 0.902 | 0.207 | 0.274 |

| Stereotype Threat (STT2) | 0.899 | 0.162 | 0.232 |

| Stereotype Threat (STT3) | 0.921 | 0.158 | 0.235 |

| Receptiveness to Innovativeness (RTI1) | 0.092 | 0.780 | 0.503 |

| Receptiveness to Innovativeness (RTI2) | 0.219 | 0.784 | 0.478 |

| Receptiveness to Innovativeness (RTI3) | 0.105 | 0.763 | 0.451 |

| Receptiveness to Innovativeness (RTI4) | 0.177 | 0.753 | 0.464 |

| Purchase Intention (PUI1) | 0.134 | 0.534 | 0.891 |

| Purchase Intention (PUI2) | 0.276 | 0.559 | 0.913 |

| Purchase Intention (PUI3) | 0.308 | 0.537 | 0.845 |

| CA | CR | AVE | REN | COA | STT | RTI | PUI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation Novelty (REN) | - | - | - | 1 | ||||

| Cognitive Age (COA) | 0.992 | 0.992 | 0.977 | 0.069 | 0.989 | |||

| Stereotype Threat (STT) | 0.894 | 0.904 | 0.824 | 0.176 | 0.676 | 0.908 | ||

| Receptiveness to Innovativeness (RTI) | 0.771 | 0.774 | 0.593 | 0.358 | −0.050 | 0.195 | 0.770 | |

| Purchase Intention (PUI) | 0.859 | 0.860 | 0.781 | 0.362 | −0.025 | 0.274 | 0.616 | 0.884 |

| Groups | Stereotype Threat | Receptiveness to Innovativeness | Purchase Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Low (n = 121) | 2.983 | 1.042 | 3.370 | 0.657 | 3.265 | 0.742 |

| High (n = 118) | 3.381 | 1.194 | 3.837 | 0.569 | 3.808 | 0.660 |

| Total Sample (n = 239) | 3.180 | 1.135 | 3.600 | 0.657 | 3.533 | 0.752 |

| Source | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 100.273 | 176.096 | 0.000 |

| Gender | 1 | 4.925 | 8.649 | 0.004 |

| Education | 1 | 0.401 | 0.703 | 0.403 |

| Income | 1 | 8.643 | 15.163 | 0.000 |

| Online Shopping Experience | 1 | 0.024 | 0.042 | 0.838 |

| Purchase Interest | 1 | 3.587 | 6.299 | 0.013 |

| Product Knowledge | 1 | 0.410 | 0.721 | 0.397 |

| Recommendation Novelty | 1 | 8.435 | 14.813 | 0.000 |

| Cognitive Age | 1 | 48.251 | 84.737 | 0.000 |

| Recommendation Novelty × Cognitive Age | 1 | 6.625 | 11.634 | 0.001 |

| Error | 229 | 0.569 | ||

| Total | 239 |

| Source | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 50.015 | 192.984 | 0.000 |

| Gender | 1 | 0.520 | 2.007 | 0.158 |

| Education | 1 | 0.034 | 0.130 | 0.719 |

| Income | 1 | 0.051 | 0.199 | 0.656 |

| Online Shopping Experience | 1 | 2.035 | 7.853 | 0.006 |

| Purchase Interest | 1 | 1.131 | 4.366 | 0.038 |

| Product Knowledge | 1 | 1.816 | 7.007 | 0.009 |

| Recommendation Novelty | 1 | 24.510 | 94.572 | 0.000 |

| Cognitive Age | 1 | 0.675 | 2.606 | 0.108 |

| Recommendation Novelty × Cognitive Age | 1 | 23.040 | 97.048 | 0.000 |

| Error | 229 | 0.259 | ||

| Total | 239 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, L.; Fu, B. Assessing the Impact of Recommendation Novelty on Older Consumers: Older Does Not Always Mean the Avoidance of Innovative Products. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060473

Zhao L, Fu B. Assessing the Impact of Recommendation Novelty on Older Consumers: Older Does Not Always Mean the Avoidance of Innovative Products. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060473

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Li, and Bing Fu. 2024. "Assessing the Impact of Recommendation Novelty on Older Consumers: Older Does Not Always Mean the Avoidance of Innovative Products" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060473

APA StyleZhao, L., & Fu, B. (2024). Assessing the Impact of Recommendation Novelty on Older Consumers: Older Does Not Always Mean the Avoidance of Innovative Products. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060473