Gen Z Tourism Employees’ Adaptive Performance During a Major Cultural Shift: The Impact of Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

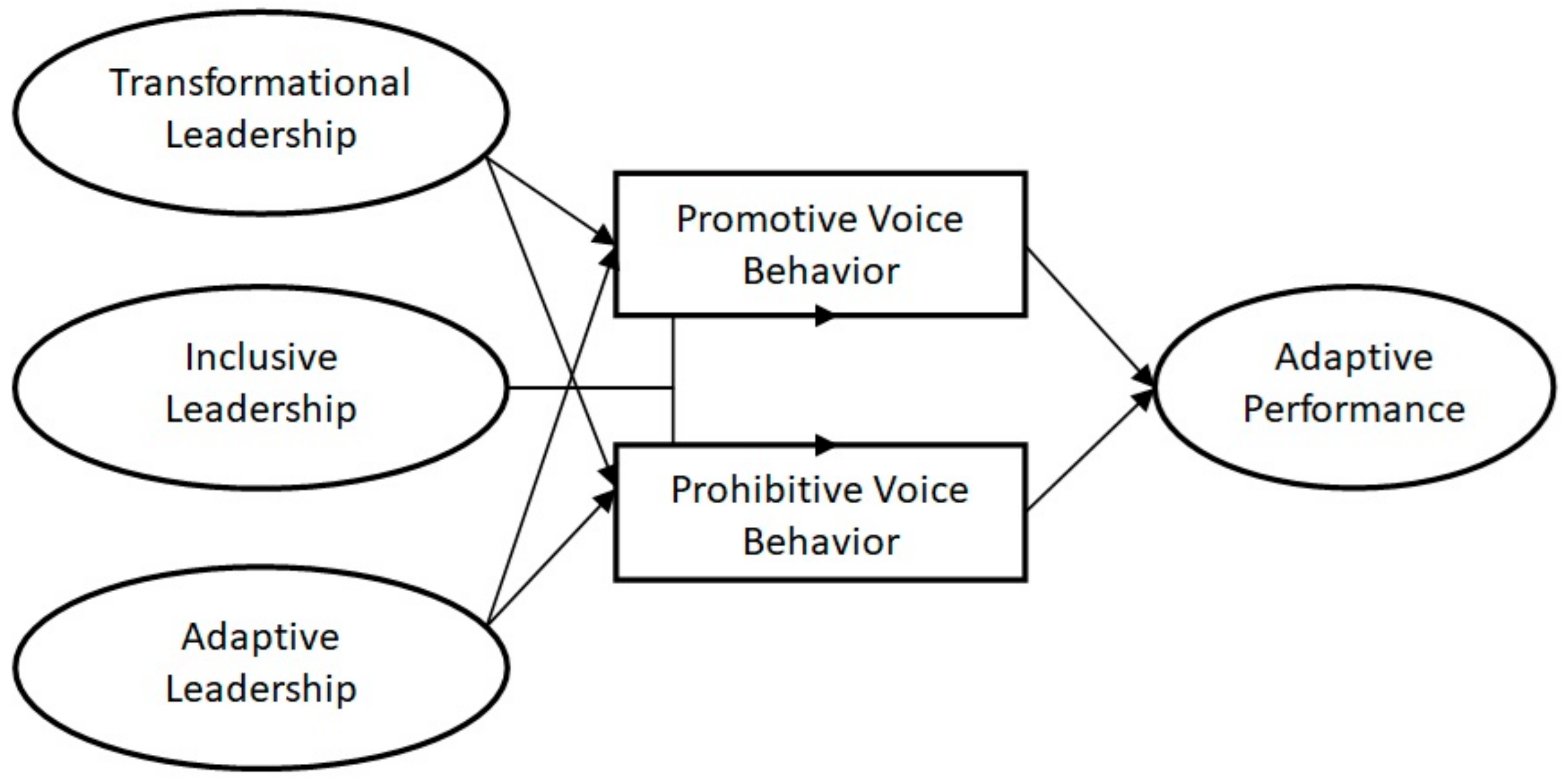

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Leadership and Employee Adaptive Performance

2.2. The Mediating Role of Employee Voice Behavior

3. Research Background

4. Methods

4.1. Procedure and Participants

4.2. Measures

5. Results

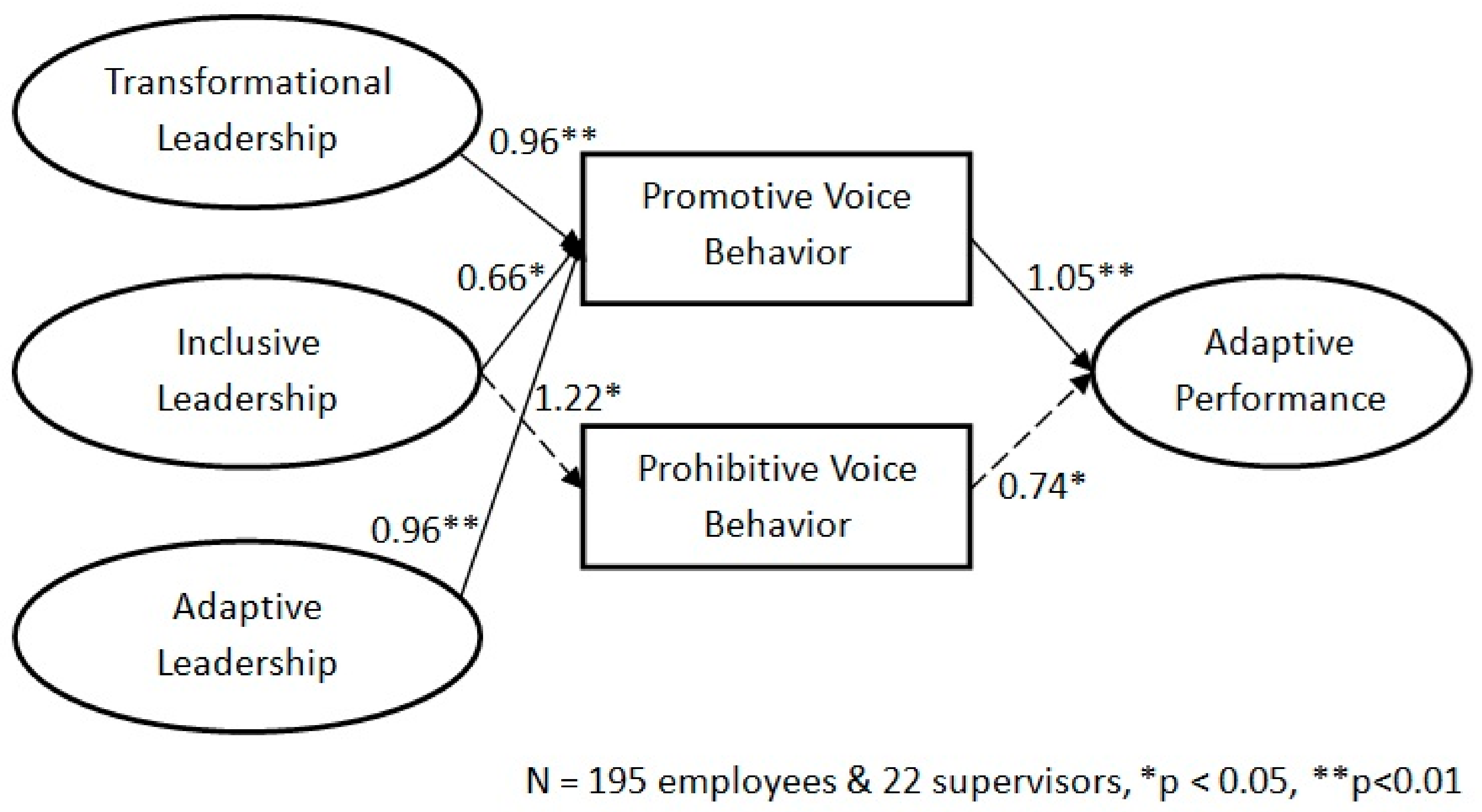

5.1. Direct Effects

5.2. Mediation Effects

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrell-Vogel, C., & Rowold, J. (2014). Leaders’ commitment to change and their effectiveness in change: A multilevel investigation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(6), 900–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpha Bank Economic Research. (2022, September 30). Greek tourism industry reloaded: Post-pandemic rebound and travel megatrends. Alpha Bank. Available online: https://www.alpha.gr/-/media/alphagr/files/group/agores/insights/2022/insights_tourism_052022.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Arthur-Mensah, N., & Zimmerman, J. (2017). Changing Through Turbulent Times—Why Adaptive Leadership Matters. The Journal of Student Leadership, 1(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1995). Manual for the multifactor leadership questionnaire: Rater form 5X short. Mind Garden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Boyles, M. (2024, January 24). Organizational leadership: What it is & why it’s important. Harvard Business School. Available online: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-organizational-leadership (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Buttigieg, S. C., Cassia, M. V., & Cassar, V. (2023). The relationship between transformational leadership, leadership agility, work engagement and adaptive performance: A theoretically informed empirical study. In Research handbook on leadership in healthcare (pp. 235–251). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (1999). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Camps, J., Oltra, V., Aldás-Manzano, J., Buenaventura-Vera, G., & Torres-Carballo, F. (2016). Individual performance in turbulent environments: The role of organizational learning capability and employee flexibility. Human Resource Management, 55(3), 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, S. A., Wearing, A. J., & Mann, L. (2000). A short scale for measuring transformational leadership. Journal of Business and Psychology, 14(3), 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22(3), 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, J. B., Huang, L., Crede, M., Harms, P., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2017). Leading to stimulate employees’ ideas: A quantitative review of leader–member exchange, employee voice, creativity, and innovative behavior. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 66(4), 517–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Y., & Hou, Y. H. (2016). The effects of ethical leadership, voice behavior and climates for innovation on creativity: A moderated mediation examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D. S., Lorinkova, N. M., & Van Dyne, L. (2013). Employees’ social context and change-oriented citizenship: A meta-analysis of leader, coworker, and organizational influences. Group & Organization Management, 38(3), 291–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S. Y., & Barron, K. (2016). Employee voice behavior revisited: Its forms and antecedents. Management Research Review, 39(12), 1720–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, K. (2020, November 20). Rewriting the rules of work: The importance of employee voice. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2020/11/20/rewriting-the-rules-of-work-the-importance-of-employee-voice/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Curado, C., & Santos, R. (2022). Transformational leadership and work performance in health care: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Leadership in Health Services, 35(2), 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, D. W., Cortina, J. M., Allen, M. T., Waters, S. D., Green, J. P., & Luchman, J. (2017). Adaptive and citizenship-related behaviors at work. In Handbook of employee selection (pp. 448–475). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J. Y., Li, C. W., Xu, Y., & Wu, C. H. (2016). Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: A Pygmalion mechanism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 650–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enterprise Greece. (2024, September 30). Invest in the greek tourism sector. Enterprise Greece. Available online: https://www.enterprisegreece.gov.gr/en/invest-in-greece/sectors-for-growth/tourism (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Fatima, T., Majeed, M., & Zulfiqar Ali Shah, S. (2021). A moderating mediation model of the antecedents of being driven to work: The role of inclusive leaders as change agents. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 38(3), 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausett, C. M., Korentsides, J. M., Miller, Z. N., & Keebler, J. R. (2024). Adaptive leadership in health care organizations: Five insights to promote effective teamwork. Psychology of Leaders and Leadership, 27(1), 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, O. A., Babalola, M. T., & Guo, L. (2018). A social exchange perspective on why and when ethical leadership foster customer-oriented citizenship behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E., & Okumus, F. (2020). Avoiding the hospitality workforce bubble: Strategies to attract and retain generation Z talent in the hospitality workforce. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (2011). Multivariate data analysis: An overview. In International encyclopedia of statistical science (pp. 904–907). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heifetz, R. A., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heskett, J. (2021). How long does it take to improve an organization’s culture? Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, P., Cooper, B., & Sheehan, C. (2017). Employee voice, supervisor support, and engagement: The mediating role of trust. Human Resource Management, 56(6), 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. (2010). Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(1), 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. N., Furuoka, F., & Idris, A. (2021). Mapping the relationship between transformational leadership, trust in leadership and employee championing behavior during organizational change. Asia Pacific Management Review, 26(2), 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremiah, S. (2020, January 25). Generation Z is bigger than millennials and they’re out to change the world. New York Post. Available online: https://nypost.com/2020/01/25/generation-z-is-bigger-than-millennials-and-theyre-out-to-change-the-world/ (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Jones, T. L. (2018). A new transformational leadership: A meadian framework for a new way forward. Leadership, 15(5), 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S., & Shetty, N. (2022). An empirical study on the impact of employee voice and silence on destructive leadership and organizational culture. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 11(Suppl. 1), 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundt, D. K., & Shoss, M. K. (2023). A process perspective on adaptive performance: Research insights and new directions. Group & Organization Management, 48(2), 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundt, D. K., Shoss, M. K., & Huang, J. L. (2015). Individual adaptive performance in organizations: A review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(Suppl. 1), S53–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiainen, J., & Hakanen, J. (2022). Fostering task and adaptive performance through employee well-being: The role of servant leadership. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 25(1), 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K. (2022). Exploring the inclusive leadership and employee change participation relationship: The role of workplace belongingness and meaning-making. Baltic Journal of Management, 17(2), 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K. K. (2024). Gen Z employee adaptive performance: The role of inclusive leadership and workplace happiness. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B., & Karatepe, O. M. (2020). Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(6), 2075–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of behavioral research (4th ed.). Harcourt College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y., & Lim, H. (2020). Activating constructive employee behavioural responses in a crisis: Examining the effects of pre-crisis reputation and crisis communication strategies on employee voice behaviours. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 28(2), 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, J. (2023, November 7). Gen Z is shaping the future of corporate america, not the other way around. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/juliekratz/2023/11/07/gen-z-is-shaping-the-future-of-corporate-america-not-the-other-way-around/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Li, X., Xue, Y., Liang, H., & Yan, D. (2020). The impact of paradoxical leadership on employee voice behavior: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 537756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. G. (2017). Linking leader authentic personality to employee voice behaviour: A multilevel mediation model of authentic leadership development. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, N. T. N. (2024). The Influence of establishing a happy workplace environment on attracting Generation Z. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 2482–2488. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R. A., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Quinteiro, P., Vargas, R., Eifler, N., & Curral, L. (2019). Employee adaptive performance and job satisfaction during organizational crisis: The role of self-leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, V. S. (2023). Happiness a Driver for Innovation at the Workplace. In Understanding happiness: An explorative view (pp. 335–344). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Maynes, T. D., Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., & Yoo, A. N. (2024). Harnessing the power of employee voice for individual and organizational effectiveness. Business Horizons, 67(3), 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, S. (2024, October 1). How is Gen Z changing the workplace? Zurich Insurance Group. Available online: https://www.zurich.com/en/media/magazine/2022/how-will-gen-z-change-the-future-of-work#:~:text=Born%20between%201995%20and%202009,attract%20and%20retain%20new%20talent (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Mitchell, R., Boyle, B., Parker, V., Giles, M., Chiang, V., & Joyce, P. (2015). Managing inclusiveness and diversity in teams: How leader inclusiveness affects performance through status and team identity. Human Resource Management, 54(2), 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostovicz, I. (2009). A dynamic theory of leadership development. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 30(6), 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, P. (2023, July 29). Adaptive leadership. ToolsHero. Available online: https://www.toolshero.com/leadership/adaptive-leadership/ (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Naqvi, S. M. M. R. (2020). Employee voice behavior as a critical factor for organizational sustainability in the telecommunications industry. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0238451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S., Chughtai, M. S., & Syed, F. (2023). Do high-performance work practices promote an individual’s readiness and commitment to change? The moderating role of adaptive leadership. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 36(6), 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2022). Employment outlook 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/oecd-employment-outlook-2022_7a5a73b3/1bb305a6-en.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Oreg, S., Michel, A., & By, R. (2023). The psychology of organizational change: New insights on the antecedents and consequences on the individual’s responses to change. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Park, S. (2019). Employee Adaptive Performance and Its Antecedents: Review and Synthesis. Human Resource Development Review, 18(3), 294–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Park, S. (2021). How can employees adapt to change? Clarifying the adaptive performance concepts. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 32(1), E1–E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J., Li, M., Wang, Z., & Lin, Y. (2021). Transformational leadership and employees’ reactions to organizational change: Evidence from a meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(3), 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnuru, R. K. G., Sharma, R., & Sahoo, C. K. (2023). Employee voice, employee involvement, and organizational change readiness: Mediating role of commitment-to-change and moderating role of transformational leadership. Business Perspectives and Research, 11(3), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A., Mohammed, I., & Asamoah, E. (2018). Transformational leadership and job satisfaction: The moderating effect of contingent reward. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 39(4), 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L., Liu, B., Wei, X., & Hu, Y. (2019). Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0212091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L., & Liu, N. (2017). Effects of inclusive leadership on employee voice behavior and team performance: The mediating role of caring ethical climate. Frontiers in Communication, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M., Asif, M., Hussain, A., & Jameel, A. (2019). Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Review of Management Science, 11(16), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurrahtulain, K., Bashir, T., Hussain, I., Ahmed, S., & Nisar, A. (2022). Impact of inclusive leadership on adaptive performance with the mediation of vigor at work and moderation of internal locus of control. Journal of public affairs, 22(1), e2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regine, B. (2020). Inclusive leadership and soft skills. In The routledge companion to inclusive leadership (pp. 264–272). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sakdiyakorn, M., Golubovskaya, M., & Solnet, D. (2021). Understanding Generation Z through collective consciousness: Impacts for hospitality work and employment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, M. L., & Taylor, L. J. (2017). Managing uncertainty—Harnessing the power of Scenario planning. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(3), 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scudder, M. F. (2020). Beyond empathy and inclusion: The challenge of listening in democratic deliberation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M., & Chung, B. G. (2022). Inclusive leadership: How leaders sustain or discourage work group inclusion. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 723–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M., Cleveland, J. N., & Sanchez, D. (2018). Inclusive workplaces: A review and model. Human resource management review, 28(2), 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M. K., Witt, L. A., & Vera, D. (2012). When does adaptive performance lead to higher task performance? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(7), 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. (2024, July 30). Total contribution of travel and tourism to employment in Greece in 2019 and 2022. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/644585/travel-and-tourism-employment-contribution-greece/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Tang, G., Abu Bakar, R., & Omar, S. (2024). Positive psychology and employee adaptive performance: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1417260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twining-Ward, L., Messerli, H., Sharma, A., Villascusa, C., & Jose, M. (2018). Tourism theory of change. Tourism for Development Knowledge Series. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien, M., & Arena, M. (2018). Leadership for organizational adaptability: A theoretical synthesis and integrative framework. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakola, M., Petrou, P., & Katsaros, K. K. (2021). Work engagement and job crafting as conditions of ambivalent employees’ adaptation to organizational change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(1), 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vito, R., Schmidt Hanbidge, A., & Brunskill, L. (2023). Leadership and organizational challenges, opportunities, resilience, and supports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 47(2), 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M., Kolbe, M., Grote, G., Spahn, D. R., & Grande, B. (2017). We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(3), 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. (2024, July 12). Global and regional tourism performance. WTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Yan, A., & Xiao, Y. G. (2016). Servant leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level investigation in China. SpringerPlus, 5, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. (2017). Customer power and frontline employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of psychological empowerment. European Journal of Marketing, 51(1), 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. M., Zhu, J. C., De Cieri, H., McNeil, N., & Zhang, K. (2024). Innovation-enhancing HRM, employee promotive voice, and perceived organizational performance: A multilevel moderated serial mediation analysis. Personnel Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Huai, M., & Xie, Y. (2015). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China: A dual process model. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(1), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | Alpha | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender a | - | - | - | ||||||

| 2. | Transformational leadership | 4.15 | 1.08 | 0.80 | 0.09 | |||||

| 3. | Inclusive leadership | 4.22 | 1.11 | 0.82 | −0.12 * | 0.52 | ||||

| 4. | Adaptive leadership | 3.88 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.24 * | 0.36 | 0.44 | |||

| 5. | Promotive voice behavior | 4.44 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 0.11 * | 0.51 * | 0.32 * | 0.22 * | ||

| 6. | Prohibitive voice behavior | 3.78 | 0.88 | 0.81 | −0.06 * | 0.36 | −0.26 | 0.21 * | 0.42 | |

| 7. | Adaptive performance | 4.35 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.04 * | 0.22 ** | 0.54 * | 0.90 * | 0.96 ** | 1.45 ** |

| Variables | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 2.71 ** | 7.42 ** | 4.22 ** | 3.78 ** | 5.19 ** |

| Gender | 0.22 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.73 ** |

| Transformational leadership | 0.49 ** | ||||

| Inclusive leadership | 0.31 ** | ||||

| Adaptive leadership | 1.06 ** | ||||

| Promotive voice behavior | 0.96 ** | ||||

| Prohibitive voice behavior | 1.45 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.44 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.33 ** |

| F | 6.22 ** | 4.22 * | 3.78 ** | 7.25 * | 6.44 * |

| Model Fit | Mediated Model | Cutoff Point | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normed Chi-Square (χ2/df) | 2.10 | <3 | Qing et al. (2019) |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.03 | <0.05 | Iacobucci (2010) |

| Goodness Fit Index (GFI) | 0.96 | >0.95 | Hair (2011) |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.97 | >0.95 | Hair (2011) |

| Rootmean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.05 | <0.06 | Iacobucci (2010) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katsaros, K.K. Gen Z Tourism Employees’ Adaptive Performance During a Major Cultural Shift: The Impact of Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020171

Katsaros KK. Gen Z Tourism Employees’ Adaptive Performance During a Major Cultural Shift: The Impact of Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(2):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020171

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatsaros, Kleanthis K. 2025. "Gen Z Tourism Employees’ Adaptive Performance During a Major Cultural Shift: The Impact of Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 2: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020171

APA StyleKatsaros, K. K. (2025). Gen Z Tourism Employees’ Adaptive Performance During a Major Cultural Shift: The Impact of Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020171