An Examination of Schizotypy, Creativity, and Wellbeing in Young Populations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Material

2.3.1. Creativity Tasks

2.3.2. Wellbeing Scales

2.3.3. Schizotypal Traits

2.4. Approach to Statistical Analysis

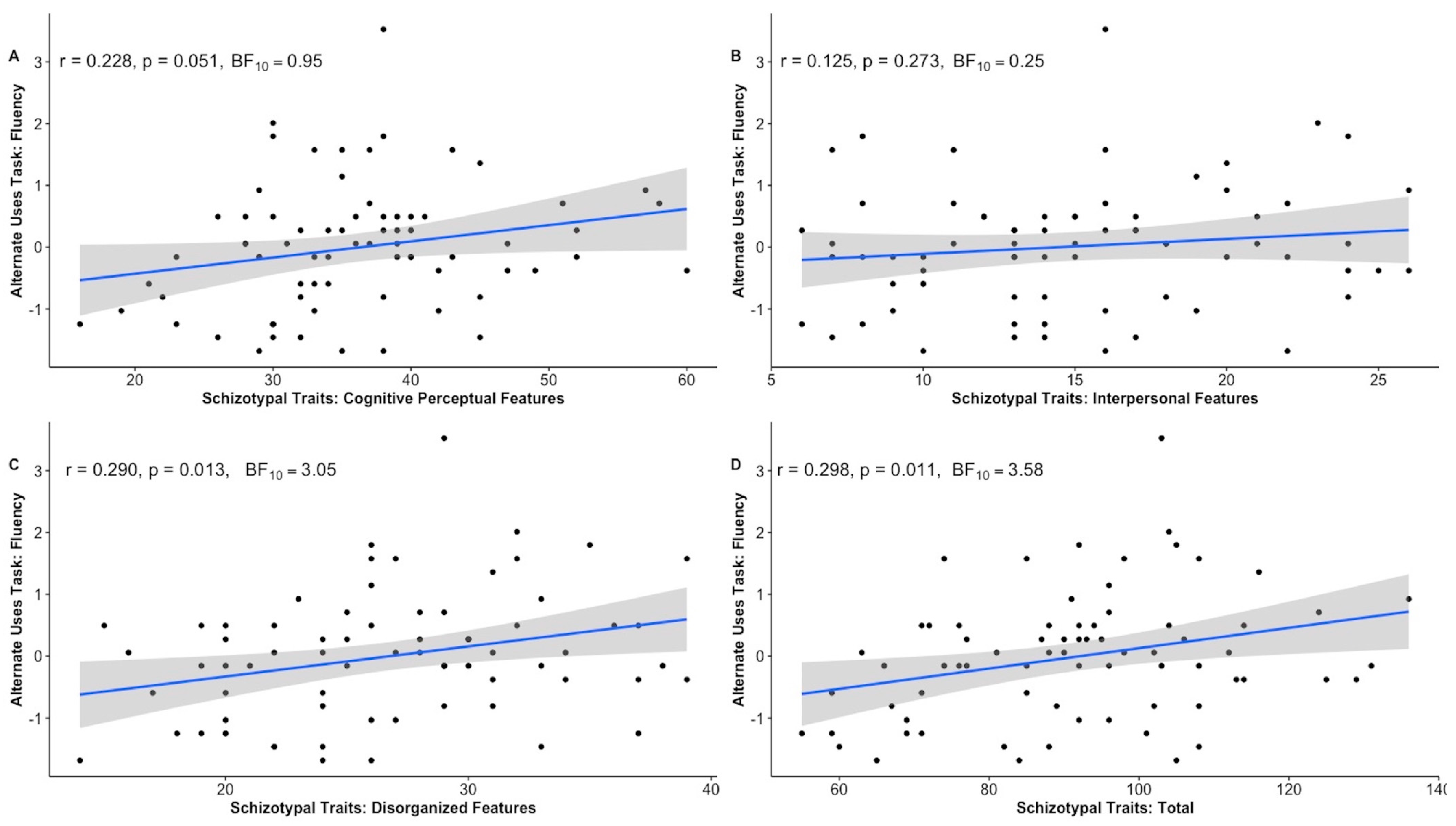

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Schizotypal Traits and Creative Potential

4.2. Schizotypal Traits and Wellbeing

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Following the proposals made by Wetzels et al. (2015) based on Jeffreys (1961), the Bayesian findings were interpreted as follows:

|

References

- Abbott, G. R., Do, M., & Byrne, L. K. (2012). Diminished subjective wellbeing in schizotypy is more than just negative affect. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(8), 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A. (2024). The creative brain. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A. (2025). Why the standard definition of creativity fails to capture the creative act. Theory & Psychology, 35(1), 09593543241290232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A., Asquith, S., Ahmed, H., & Bourisly, A. K. (2019). Comparing the efficacy of four brief inductions in boosting short-term creativity. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 3(1), 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A., & Windmann, S. (2007). Creative cognition: The diverse operations and the prospect of applying a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Methods, 42(1), 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A., & Windmann, S. (2008). Selective information processing advantages in creative cognition as a function of schizotypy. Creativity Research Journal, 20(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Akel, A., Baxendale, L., Mohr, C., & Sullivan, S. (2018). The association between schizotypal traits and social functioning in adolescents from the general population. Psychiatry Research, 270, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, S., Chen, X., & Cayirdag, N. (2018). Schizophrenia and creativity: A meta-analytic review. Schizophrenia Research, 195, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, S., & Sen, S. (2013). A multilevel meta-analysis of the relationship between creativity and schizotypy. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(3), 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, S. L., Wang, X., Quintana, D. S., & Abraham, A. (2022a). Predictors of creativity in young people: Using frequentist and Bayesian approaches in estimating the importance of individual and contextual factors. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 16(2), 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, S. L., Wang, X., Quintana, D. S., & Abraham, A. (2022b). The role of personality traits and leisure activities in predicting wellbeing in young people. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, S. L., Wang, X., Quintana, D. S., & Abraham, A. (2024). Predictors of change in creative thinking abilities in young people: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 58(2), 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M., & Furnham, A. (2008). The relationship between measures of creativity and schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(8), 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, M., Karstendiek, M., Ceh, S. M., Grabner, R. H., Krammer, G., Lebuda, I., Silvia, P. J., Cotter, K. N., Li, Y., Hu, W., Martskvishvili, K., & Kaufman, J. C. (2021). Creativity myths: Prevalence and correlates of misconceptions on creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G. S. J., Pavelis, C., Hemsley, D. R., & Corr, P. J. (2006). Schizotypy and creativity in visual artists. British Journal of Psychology, 97(2), 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R., Haenschel, C., Gaigg, S. B., & Fett, A.-K. J. (2022). Loneliness, positive, negative and disorganised Schizotypy before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition, 29, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claridge, G., & Blakey, S. (2009). Schizotypy and affective temperament: Relationships with divergent thinking and creativity styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(8), 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C. A., Hoffman, L., & Spaulding, W. D. (2016). Schizotypal personality questionnaire—Brief revised (updated): An update of norms, factor structure, and item content in a large non-clinical young adult sample. Psychiatry Research, 238, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbané, M., Vrtička, P., Lazouret, M., Badoud, D., Sander, D., & Eliez, S. (2014). Self-reflection and positive schizotypy in the adolescent brain. Schizophrenia Research, 152(1), 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizinger, J. M. B., Doll, C. M., Rosen, M., Gruen, M., Daum, L., Schultze-Lutter, F., Betz, L., Kambeitz, J., Vogeley, K., & Haidl, T. K. (2022). Does childhood trauma predict schizotypal traits? A path modelling approach in a cohort of help-seeking subjects. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 272(5), 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, H. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Lemos-Giráldez, S., Paino, M., & Muñiz, J. (2011). Schizotypy, emotional–behavioural problems and personality disorder traits in a non-clinical adolescent population. Psychiatry Research, 190(2), 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumero, A., Marrero, R., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2018). Well-being in schizotypy: The effect of subclinical psychotic experiences. Psicothema, 2(30), 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadermann, A. M., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Zumbo, B. D. (2010). Investigating validity evidence of the satisfaction with life scale adapted for children. Social Indicators Research, 96(2), 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P., Christensen, P. R., Merrifeld, P. R., & Wilson, R. C. (1960). Alternate uses manual. Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, L. M., Kemp, K. C., Barrantes-Vidal, N., & Kwapil, T. R. (2023). Disorganized schizotypy and neuroticism in daily life: Examining their overlap and differentiation. Journal of Research in Personality, 106, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, J., Delpech, L., Bronchain, J., & Raynal, P. (2020). Creative competencies and cognitive processes associated with creativity are linked with positive schizotypy. Creativity Research Journal, 32(2), 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.1) [Computer software]. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Jeffreys, H. (1961). Theory of probability (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, V. (2015). Beyond the PANAS: Incremental validity of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) in relation to well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z., Windmann, S., Güntürkün, O., & Abraham, A. (2007). Insight problem solving in individuals with high versus low schizotypy. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(2), 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. (2023). ggpubr: “ggplot2” based publication ready plots (Version 0.6.0) [R Package computer software]. Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/ggpubr/authors.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Annas, J. (2009). Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(3), 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapil, T. R., & Barrantes-Vidal, N. (2015). Schizotypy: Looking back and moving forward. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(Suppl. S2), S366–S373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzenweger, M. F. (2018). Schizotypy, schizotypic psychopathology and schizophrenia. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Wong, K. K.-Y., Dong, F., Raine, A., & Tuvblad, C. (2019). The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Child (SPQ-C): Psychometric properties and relations to behavioral problems with multi-informant ratings. Psychiatry Research, 275, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, O., & Claridge, G. (2006). The Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE): Further description and extended norms. Schizophrenia Research, 82(2), 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehl, P. E. (1962). Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. American Psychologist, 17(12), 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, C., & Claridge, G. (2015). Schizotypy—Do not worry, it is not all worrisome. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(Suppl. S2), S436–S443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munafò, M. R., & Davey Smith, G. (2018). Robust research needs many lines of evidence. Nature, 553(7689), 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oezgen, M., & Grant, P. (2018). Odd and disorganized—Comparing the factor structure of the three major schizotypy inventories. Psychiatry Research, 267, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, K., Watkeys, O., Dean, K., Laurens, K. R., Tzoumakis, S., Harris, F., Carr, V. J., & Green, M. J. (2023a). Childhood schizotypy and adolescent mental disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 50(1), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hare, K., Watkeys, O., Whitten, T., Dean, K., Laurens, K. R., Tzoumakis, S., Harris, F., Carr, V. J., & Green, M. J. (2023b). Cumulative environmental risk in early life: Associations with schizotypy in childhood. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 49(2), 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polner, B., Hupuczi, E., Kéri, S., & Kállai, J. (2021). Adaptive and maladaptive features of schizotypy clusters in a community sample. Scientific Reports, 11, 16653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, D. S., & Williams, D. R. (2018). Bayesian alternatives for common null-hypothesis significance tests in psychiatry: A non-technical guide using JASP. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A. (1991). The SPQ: A scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 17(4), 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A., Wong, K. K.-Y., & Liu, J. (2021). The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire for Children (SPQ-C): Factor structure, child abuse, and family history of schizotypy. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(2), 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: The R project for statistical computing (Version 4.2.2) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Rominger, C., Fink, A., Weiss, E. M., Bosch, J., & Papousek, I. (2017). Allusive thinking (remote associations) and auditory top-down inhibition skills differentially predict creativity and positive schizotypy. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 22(2), 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A., Okuda, S. M., & Thurston, B. J. (1987). The psychometric properties of four systems for scoring divergent thinking tests. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 5(2), 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. M., Ward, T. B., & Schumacher, J. S. (1993). Constraining effects of examples in a creative generation task. Memory & Cognition, 21(6), 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, N. T., & Weisman de Mamani, A. G. (2013). Latent profile analysis of healthy schizotypy within the extended psychosis phenotype. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. L. (2017). Creativity and mood disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 1040–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutountzidis, D., Gale, T. M., Irvine, K., Sharma, S., & Laws, K. R. (2022). Childhood trauma and schizotypy in non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0270494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikonja, T., Velthorst, E., McClure, M. M., Rutter, S., Calabrese, W. R., Rosell, D., Koenigsberg, H. W., Goodman, M., New, A. S., Hazlett, E. A., & Perez-Rodriguez, M. M. (2019). Severe childhood trauma and clinical and neurocognitive features in schizotypal personality disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 140(1), 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Ly, A., Verhagen, J., Love, J., Selker, R., Gronau, Q. F., Šmíra, M., Epskamp, S., Matzke, D., Rouder, J. N., & Morey, R. D. (2018). Bayesian inference for psychology. Part I: Theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Long, H., Plucker, J. A., Wang, Q., Xu, X., & Pang, W. (2018). High schizotypal individuals are more creative? The mediation roles of overinclusive thinking and cognitive inhibition. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetzels, R., van Ravenzwaaij, D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2015). Bayesian analysis. In The encyclopedia of clinical psychology (pp. 1–11). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H., Chang, W., Henry, L., Pedersen, T. L., Takahashi, K., Wilke, C., Woo, K., Yutani, H., Dunnington, D., van den Brand, T., & Posit, PBC. (2024). ggplot2: Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics (Version 3.5.1) [R package computer software]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Zhang, L., Zhao, N., Zhu, M., Tang, M., Liu, W., & Hong, W. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences in patients with schizophrenia: Related factors and clinical implications. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1247063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 76 | 38 | 20 | 18 |

| Age [Mean, (SD)] | 18.34 (1.83) | 16.76 (0.28) | 18.82 (0.39) | 21.15 (0.44) |

| Age Range | 16–22 | 16–17 | 18–19 | 20–22 |

| Gender [n] | ||||

| Female | 68 | 34 | 17 | 17 |

| Male | 7 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Non-binary | 1 | 1 |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity variables | |||

| AUT fluency | 76 | 4.91 | 1.54 |

| AUT overall originality | 76 | 4.95 | 1.43 |

| AUT peak originality | 76 | 5.21 | 3.08 |

| OKC raw scores | 76 | 1.59 | 0.94 |

| Creative hobbies | 76 | 6.99 | 6.67 |

| Wellbeing variables | |||

| Life satisfaction | 76 | 3.72 | 0.81 |

| Positive affect | 72 | 22.04 | 3.55 |

| Negative affect | 72 | 16.90 | 4.30 |

| Mental health | 75 | 2.91 | 0.72 |

| Schizotypy variables | |||

| SPQ total | 72 | 91.49 | 18.45 |

| SPQ cognitive perceptual | 72 | 36.01 | 8.79 |

| SPQ interpersonal | 72 | 14.81 | 5.30 |

| SPQ disorganized | 72 | 26.74 | 6.06 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AUT fluency | p | 1 | 0.320 | 0.005 | 0.704 | <0.001 | 0.076 | 0.081 | −0.111 | 0.341 | 0.066 | 0.582 | 0.228 | 0.054 | −0.043 | 0.715 | 0.299 | 0.009 | 0.228 | 0.051 | 0.125 | 0.273 | 0.290 | 0.013 | 0.298 | 0.011 |

| BF10 | 7.13 | >100 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.90 | 0.15 | 4.22 | 0.95 | 0.25 | 3.05 | 3.58 | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | AUT overall originality | p | 76 | 1 | 0.709 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.186 | 0.206 | 0.075 | 0.146 | 0.221 | 0.133 | 0.265 | 0.212 | 0.068 | 0.062 | 0.594 | −0.043 | 0.715 | −0.073 | 0.540 | −0.046 | 0.700 | −0.067 | 0.576 | |

| BF10 | >100 | 0.19 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | AUT peak originality | p | 76 | 76 | 1 | 0.062 | 0.175 | 0.107 | 0.107 | 0.144 | 0.227 | 0.257 | 0.029 | 0.120 | 0.306 | 0.221 | 0.055 | 0.040 | 0.736 | −0.078 | 0.523 | 0.152 | 0.200 | 0.064 | 0.591 | ||

| BF10 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 1.51 | 0.24 | 0.87 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.330 | 0.17 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4 | OKC raw score | p | 76 | 76 | 76 | 1 | 0.040 | 0.733 | 0.026 | 0.828 | −0.069 | 0.566 | −0.101 | 0.388 | 0.097 | 0.403 | 0.040 | 0.904 | −0.000 | 0.529 | −0.000 | 0.890 | −0.008 | 0.950 | |||

| BF10 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Life satisfaction | p | 76 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 1 | 0.613 | <0.001 | −0.334 | 0.004 | 0.554 | <0.001 | 0.140 | 0.229 | −0.227 | 0.052 | −0.400 | <0.001 | −0.260 | 0.027 | −0.387 | 0.001 | ||||

| BF10 | >100 | 8.23 | >100 | 0.29 | 0.93 | 67.12 | 1.63 | 36.65 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Positive affect | p | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 1 | −0.327 | 0.005 | 0.545 | <0.001 | 0.163 | 0.171 | −0.042 | 0.731 | −0.386 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.996 | −0.124 | 0.310 | |||||

| BF10 | 6.93 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 32.85 | 0.15 | 0.24 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Negative affect | p | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 1 | −0.400 | 0.001 | 0.152 | 0.201 | 0.552 | <0.001 | 0.303 | 0.010 | 0.295 | 0.013 | 0.490 | <0.000 | ||||||

| BF10 | 50.77 | 0.33 | >100 | 3.73 | 3.02 | >100 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Mental health | p | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 71 | 71 | 1 | 0.067 | 0.566 | −0.265 | 0.023 | −0.450 | <0.001 | −0.274 | 0.020 | −0.406 | <0.000 | |||||||

| BF10 | 0.17 | 1.85 | >100 | 2.12 | 68.08 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Creative hobbies | p | 76 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 72 | 72 | 75 | 1 | 0.198 | 0.091 | 0.177 | 0.128 | 0.333 | 0.004 | 0.238 | 0.045 | ||||||||

| BF10 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 3.77 | 1.06 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | SPQ cognitive perceptual | p | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 1 | 0.362 | 0.002 | 0.556 | <0.001 | 0.852 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| BF10 | 18.95 | >100 | >100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | SPQ interpersonal | p | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 71 | 71 | 74 | 75 | 73 | 1 | 0.362 | 0.002 | 0.673 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| BF10 | 18.67 | >100 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | SPQ disorganized | p | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 73 | 72 | 73 | 1 | 0.793 | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| BF10 | >100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | SPQ total | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 76 | 69 | 69 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Pearson’s r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUT fluency | AUT overall orig. | 0.405 | <0.001 |

| AUT fluency | AUT peak orig. | 0.718 | <0.001 |

| AUT overall orig. | AUT peak orig. | 0.747 | <0.001 |

| Life satisfaction | Positive affect | 0.611 | <0.001 |

| Life satisfaction | Negative affect | −0.345 | 0.004 |

| Life satisfaction | Mental health | −0.523 | <0.001 |

| Mental health | Positive affect | 0.536 | <0.001 |

| Mental health | Negative affect | −0.396 | 0.001 |

| Positive affect | Negative affect | −0.338 | 0.005 |

| Creative hobbies | AUT fluency | 0.284 | 0.020 |

| SPQ cog. percep. | Negative affect | 0.535 | <0.001 |

| SPQ interpersonal | Life satisfaction | −0.371 | 0.002 |

| SPQ interpersonal | Positive affect | 0.370 | 0.002 |

| SPQ interpersonal | Negative affect | 0.313 | 0.010 |

| SPQ interpersonal | Mental health | −0.445 | <0.001 |

| SPQ interpersonal | SPQ cog. percep. | 0.398 | 0.001 |

| SPQ disorganized | AUT fluency | 0.286 | 0.019 |

| SPQ disorganized | Negative affect | 0.259 | 0.034 |

| SPQ disorganized | Creative hobbies | 0.254 | 0.038 |

| SPQ disorganized | SPQ cog. percep. | 0.514 | <0.001 |

| SPQ disorganized | SPQ interpersonal | 0.358 | 0.003 |

| SPQ total | AUT fluency | 0.293 | 0.016 |

| SPQ total | Life satisfaction | −0.354 | 0.003 |

| SPQ total | Negative affect | 0.473 | <0.001 |

| SPQ total | Mental health | −0.376 | 0.002 |

| SPQ total | SPQ cog. percep. | 0.841 | <0.001 |

| SPQ total | SPQ interpersonal | 0.676 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chapman, H.E.; Asquith, S.L.; Abraham, A. An Examination of Schizotypy, Creativity, and Wellbeing in Young Populations. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040553

Chapman HE, Asquith SL, Abraham A. An Examination of Schizotypy, Creativity, and Wellbeing in Young Populations. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):553. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040553

Chicago/Turabian StyleChapman, Harrison E., Sarah L. Asquith, and Anna Abraham. 2025. "An Examination of Schizotypy, Creativity, and Wellbeing in Young Populations" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040553

APA StyleChapman, H. E., Asquith, S. L., & Abraham, A. (2025). An Examination of Schizotypy, Creativity, and Wellbeing in Young Populations. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040553