Cracking the Code of Cyberbullying Effects: The Spectator Sports Solution for Emotion Management and Well-Being Among Economically Disadvantaged Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Emotion Management and Its Factor Structure

2.2. Cyberbullying and Emotion Management

2.3. Impaired Emotion Management on School Outcomes, GPA, and Well-Being

2.4. Spectator Sports Involvement

3. Methods

3.1. Samples and Data Collection Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

4.2. Measurement Models

4.3. Structural Models

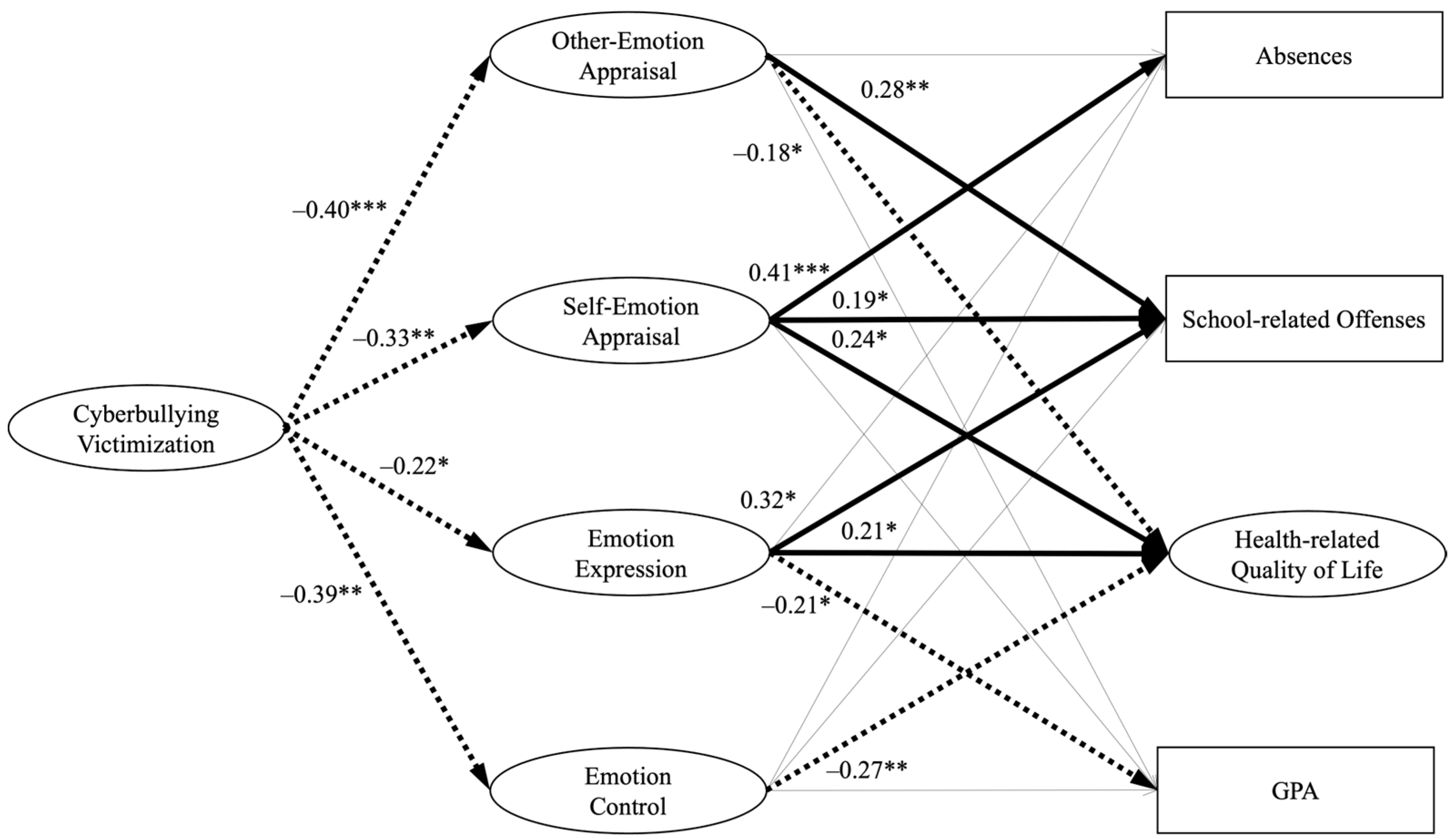

4.3.1. Non-Spectatorship Group (NSG)

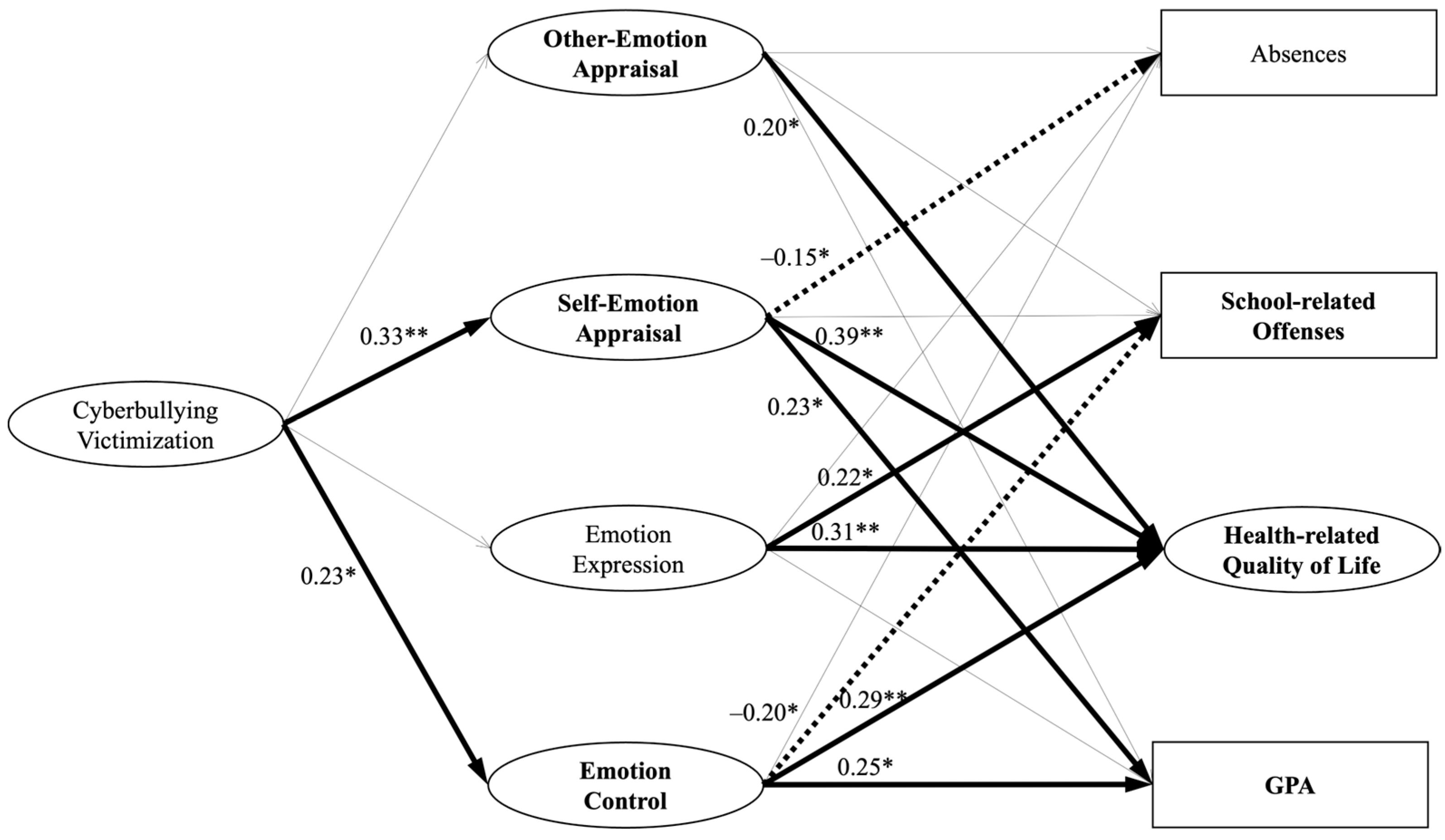

4.3.2. Spectatorship-Adherent Group (SG)

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.1.1. Cyberbullying and Impaired Emotion Management

5.1.2. The Emotional Benefits of Sport Spectatorship

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, M.-Z., Yao, S.-J., Ma, Q.-S., Wang, X.-L., Liu, C., & Guo, K.-L. (2022). The relationship between physical exercise and school adaptation of junior students: A chain mediating model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 977663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R. (2006). Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. Journal of School Health, 76(8), 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, K. C., Røhr, H. L., Reme, B.-A., & Flatø, M. (2023). Distressing testing: A propensity score analysis of high-stakes exam failure and mental health. Child Development. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, M., Smit, M. S., Raat, H., Bramer, W. M., & Jansen, W. (2022). Impact of organized activities on mental health in children and adolescents: An umbrella review. Preventive Medicine Reports, 25, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, M. A., Roberto, C. A., Harris, J. L., Brownell, K. D., & Elbel, B. (2018). Marketing food and beverages to youth through sports. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau, J. S., Vallerand, R. J., Ntoumanis, N., & Lafrenière, M.-A. K. (2013). On passion and moral behavior in achievement settings: The mediating role of pride. Motivation and Emotion, 37(1), 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, L. (2007). Childhood Adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Science, 56(4), 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., Estévez, A., Villardón, L., & Padilla, P. (2010). Cyberbullying in adolescents: Modalities and aggressors’ profile. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaku, N., Hoyt, L. T., & Barry, K. (2021). Executive functioning profiles in adolescence: Using person-centered approaches to understand heterogeneity. Cognitive Development, 60, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y., & Wann, D. L. (2022). Effects of game outcomes and status instability on spectators’ status consumption: The moderating role of implicit team identification. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 819644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarrochi, J., Chan, A. Y. C., & Bajgar, J. (2001). Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(7), 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S., Forneris, T., Hodge, K., & Heke, I. (2004). Enhancing youth development through sport. World Leisure Journal, 46(3), 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., Thompson, F., Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Pyżalski, J., & Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLeo, L. L., Suldo, S. M., Ferron, J. M., & Shaunessy-Dedrick, E. (2022). Three-wave longitudinal study of a dual-factor model: Mental health status and academic outcomes for high school students in academically accelerated curricula. School Mental Health, 14, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droppert, K., Downey, L., Lomas, J., Bunnett, E. R., Simmons, N., Wheaton, A., Nield, C., & Stough, C. (2019). Differentiating the contributions of emotional intelligence and resilience on adolescent male scholastic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 145, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhart, M., Ottova, V., Gaspar, T., Jericek, H., Schnohr, C., Alikasifoglu, M., Morgan, A., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & HBSC Positive Health Focus Group. (2009). Measuring mental health and well-being of school-children in 15 European countries using the KIDSCREEN-10 Index. International Journal of Public Health, 54(Suppl. S2), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, M. A., Settanni, M., Longobardi, C., & Marengo, D. (2024). Sense of belonging at school and on social media in adolescence: Associations with educational achievement and psychosocial maladjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 55(6), 1620–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Perez, V., & Martin-Rojas, R. (2022). Emotional competencies as drivers of management students’ academic performance: The moderating effects of cooperative learning. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(1), 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R., Holzer, A. A., Bradley, C., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Patti, J. (2022). The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership in school leaders: A systematic review. Cambridge Journal of Education, 52(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, S., Gregory, T., Taylor, A., Digenis, C., & Turnbull, D. (2021). The impact of bullying victimization in early adolescence on subsequent psychosocial and academic outcomes across the adolescent period: A systematic review. Journal of School Violence, 20(3), 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamuddin, B., Rahman, F., Pammu, A., Baso, Y. S., & Derin, T. (2023). Mitigating the effects of cyberbullying crime: A multi-faceted solution across disciplines. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, 6(1), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F. K. W., Louie, L. H. T., Wong, W. H. S., Chan, K. L., Tiwari, A., Chow, C. B., Ho, W., Wong, W., Chan, M., Chen, E. Y. H., Cheung, Y. F., & Ip, P. (2017). A sports-based youth development program, teen mental health, and physical fitness: An RCT. Pediatrics, 140(4), e20171543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M. D., Barnes, J. D., Tremblay, M. S., & Guerrero, M. D. (2022). Associations between organized sport participation and mental health difficulties: Data from over 11,000 US children and adolescents. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0268583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-L., Wang, S.-Y. K., & Lin, Y. (2023). Perceptions of punishment risks among youth: Can cyberbullying be deterred? Journal of School Violence, 22(3), 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C., Peters, L., & Rapee, R. M. (2012). Development of a measure of the experience of being bullied in youth. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivcevic, Z., & Eggers, C. (2021). Emotion regulation ability: Test performance and observer reports in predicting relationship, achievement, and well-being outcomes in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, L., Matthews, N., Christian, P., & Shire, J. (2015). Health literacy in schools: Prioritising health and well-being issues through the curriculum. Sport, Education and Society, 20(4), 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Park, K. (2022). Longitudinal evidence on adolescent social network position and cardiometabolic risk in adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114909. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford Press. ISBN 9781462551910. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., Chun, J., Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2020). Cyberbullying victimisation and school dropout intention among South Korean adolescents: The moderating role of peer/teacher support. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 30(3), 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. M., Choi, H. H., Lee, H., Park, J., & Lee, J. (2023). The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Psychosocial Behaviors among College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Indirect Effect of a Sense of Purpose in Life. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 32(9), 1254–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J., Marques, A., Rodrigues, A., Sarmento, H., Onofre, M., & Carreiro da Costa, F. (2018). Exploring the perspectives of physically active and inactive adolescents: How does physical education influence their lifestyles? Sport, Education and Society, 23(5), 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. C., & Dolendo, R. B. (2022). Mental toughness and character building through sports. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 6515–6524. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M., Rindfuss, R. R., McDonald, P., te Velde, E., & on behalf of the ESHRE Reproduction and Society Task Force. (2011). Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Human Reproduction Update, 17, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mistry, R. S., Vandewater, E. A., Huston, A. C., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development, 73(3), 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morese, R., Thornberg, R., & Longobardi, C. (Eds.). (2022). Cyberbullying and mental health: An interdisciplinary perspective. Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, K. C., & Carey, M. T. (2023). How positive and negative childhood experiences interact with resiliency theory and the general theory of crime in juvenile probationers. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 21(2), 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Synder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89–105). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, C. L. (2014). Current perspectives: The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 5, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkent, Y., & Açıkel, B. (2022). The association between binge-watching behavior and psychological problems among adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(6), 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue). In C. Stough, D. H. Saklofske, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 85–101). Springer Science Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, N., Verbeek, J., van der Zwan, J., & van Hilvoorde, I. (2016). Socialisation into organised sports of young adolescents with a lower socio-economic status. Sport, Education and Society, 21(3), 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.2.3) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Raiser, K., Kornek, U., Flachsland, C., & Lamb, W. F. (2020). Is the Paris Agreement effective? A systematic map of the evidence. Environmental Research Letters, 15(8), 083006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, S., Gana, S., Garcés, S., Zúñiga, T., Araya, R., & Gaete, J. (2021). Use of technology and its association with academic performance and life satisfaction among children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 764054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Kidscreen Group Europe. (2006). The kidscreen questionnaires quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents: Handbook. Pabst Science. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B. A., Starin, N. S., Senior, C. J., Zarger, M. M., Cummings, C. M., Collado, A., & Alvord, M. K. (2023). Improved resilience and academics following a school-based resilience intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8(2), 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocliffe, P., O’Keeffe, B., Walsh, L., Stylianou, M., Woodforde, J., García-González, L., O’Brien, W., Coppinger, T., Sherwin, I., Mannix-McNamara, P., & MacDonncha, C. (2023). The impact of typical school provision of physical education, physical activity, and sports on adolescent physical activity behaviors: A systematic literature review. Adolescent Research Review, 8, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(6), 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohoudi Mojdehi, A., Leduc, K., Shohoudi Mojdehi, A., & Talwar, V. (2019). Examining cross-cultural differences in youth’s moral perceptions of cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(4), 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourander, A., Brunstein Klomek, A., Ikonen, M., Lindroos, J., Luntamo, T., Koskelainen, M., Ristkari, T., & Helenius, H. (2010). Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(7), 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, R., Weidinger, A. F., Schwinger, M., & Spinath, B. (2019). The importance of students’ motivation for their academic achievement—Replicating and extending previous findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulz, L. D., Gleddie, D. L., Kinsella, C., & Humbert, M. L. (2023). The health and educational impact of removing financial constraints for school sport. European Physical Education Review, 29(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taie, S., Lewis, L. W., & Spiegelman, M. (2022). Characteristics of 2020–21 public and private K-12 schools in the United States: Results from the national teacher and principal survey first look. National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2022/2022111.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Thulin, E. J., Lee, D. B., Eisman, A. B., Reischl, T. M., Hutchison, P., Franzen, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2022). Longitudinal effects of youth empowerment solutions: Preventing youth aggression and increasing prosocial behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology, 70(1–2), 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J. L., Mercadante, E., & Hohm, I. (2023). Pride: The emotional foundation of social rank attainment. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 519–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripon, C. (2023). Navigating the STEM jungle of professionals: Unlocking critical competencies through emotional intelligence. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology, 13, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & Pabian, S. (2014). Personal characteristics and contextual factors that determine “helping,” “joining in,” and “doing nothing” when witnessing cyberbullying. Aggressive Behavior, 40(5), 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittmer, J. L. S., & Hopkins, M. M. (2022). Leading remotely in a time of crisis: Relationships with emotional intelligence. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 29(2), 176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H., Gong, Z., Ba, Z., Doolan-Noble, F., & Han, Z. (2021). School bullying and health-related quality of life in Chinese school-aged children and adolescents. Children & Society, 35(6), 885–900. [Google Scholar]

- Yman, J., Helgadóttir, B., Kjellenberg, K., & Nyberg, G. (2023). Associations between organized sports participation, general health, stress, screen-time, and sleep duration in adolescents. Acta Paediatrica, 112, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Lamana, R., Sanhueza-Campos, C., Stuardo-Álvarez, M., Ibarra-Mora, J., Mardones-Contreras, M., Reyes-Molina, D., Vásquez-Gómez, J., Lasserre-Laso, N., Poblete-Valderrama, F., Petermann-Rocha, F., Parra-Rizo, M. A., & Cigarroa, I. (2021). Anxiety, low self-esteem and a low happiness index are associated with poor school performance in Chilean adolescents: A cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items | M | SE | λ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying Victimization | I have been the target of online bullying or mean messages from other kids. | 3.19 | 0.44 | 0.64 |

| I have received threatening messages or calls from other kids on my phone. | 2.81 | 0.39 | 0.58 | |

| Other kids have posted hurtful or mean things about me online. | 2.72 | 0.44 | 0.65 | |

| Other-emotion Appraisal | I can often tell how others are feeling by their expressions and behavior. | 4.62 | 0.09 | 0.74 |

| I’m good at understanding how others feel. | 4.75 | 0.09 | 0.73 | |

| I can usually tell when someone needs help with their feelings. | 4.46 | 0.08 | 0.77 | |

| Self-emotion Appraisal | I often think about why I feel the way I do. | 4.42 | 0.11 | 0.69 |

| It’s easy for me to understand how I feel. | 4.37 | 0.14 | 0.67 | |

| I pay a lot of attention to my feelings. | 4.58 | 0.10 | 0.69 | |

| Emotion Expression | I feel comfortable talking about my feelings with friends and family. | 3.25 | 0.10 | 0.71 |

| Sharing my emotions with others is something I do easily. | 3.53 | 0.11 | 0.72 | |

| I’m open to discussing how I feel with those I trust. | 3.66 | 0.10 | 0.71 | |

| Emotion Control | I try to control my thoughts and not worry too much about things. | 3.73 | 0.13 | 0.68 |

| I can often keep my emotions in check, even in stressful situations. | 3.13 | 0.12 | 0.70 | |

| I find it easy to control my feelings. | 3.35 | 0.12 | 0.70 | |

| Health-related Quality of Life | Felt sad (reversed). | 2.57 | 0.47 | 0.54 |

| Felt lonely (reversed). | 2.33 | 0.44 | 0.58 | |

| Felt fit and well. | 4.59 | 0.11 | 0.74 | |

| Felt full of energy. | 4.32 | 0.11 | 0.75 | |

| Had enough time for yourself. | 5.74 | 0.09 | 0.83 | |

| Been able to do the things that you want in your free time. | 5.98 | 0.14 | 0.66 | |

| Parents/guardians treated you fairly. | 4.93 | 0.13 | 0.68 | |

| Had fun with your friends. | 5.16 | 0.17 | 0.61 | |

| Felt confident at school. | 4.27 | 0.11 | 0.71 | |

| Been able to pay attention at school. | 4.51 | 0.14 | 0.70 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyber. Victimization | – | ||||||||

| Other-emotion. | −0.41/0.11 | – | |||||||

| Self-emotion. | −0.44/0.42 | 0.76/0.51 | – | ||||||

| Emotion Expression | −0.31/0.18 | 0.60/0.49 | 0.61/0.55 | – | |||||

| Emotion Control | −0.39/0.31 | 0.58/0.51 | 0.73/0.38 | 0.57/0.48 | – | ||||

| Absences | 0.37/0.04 | 0.02/0.14 | 0.48/−0.11 | 0.18/0.17 | 0.10/0.17 | – | |||

| Offenses | 0.41/0.11 | 0.37/0.21 | 0.15/0.04 | 0.26/0.19 | 0.11/−0.05 | 0.03/−0.02 | – | ||

| Life Quality | −0.10/0.09 | −0.21/0.03 | 0.32/0.27 | 0.34/0.28 | −0.24/0.21 | 0.01/0.07 | −0.17/0.14 | – | |

| GPA | −0.21/−0.01 | 0.14/0.01 | 0.21/0.34 | −0.23/0.07 | 0.02/0.29 | −0.02/−0.01 | −0.23/−0.01 | 0.04/0.17 | – |

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | Model Comparison | Difference in χ2/df | Difference in CFI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Configural invariance (unconstrained) | 985.44 | 260 | 0.06 | 0.91 | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Factor loadings invariant | 1007.21 | 272 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 2 vs. 1 | 21.77/12 | 0.01 | 0.13 |

| 3. Factor loadings and intercepts invariant | 1043.82 | 284 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 3 vs. 1 | 58.38/24 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Model | Model Fit Indices | Model Comparison in χ2/df | Structural Coefficients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSG | SG | |||

| Unconstrained | χ2 (642) = 2381.8; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | – | – | – |

| Structural weight | χ2 (662) = 2464.2; C = 0.90, R = 0.07, S = 0.08 | 82.37/20 | – | – |

| Cyber. Victim. → Other-emotion | χ2 (643) = 2384.9; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 3.12/1 | −0.40 *** | 0.06 |

| Cyber. Victim. → Self-emotion | χ2 (643) = 2384.7; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 2.85/1 | −0.33 ** | 0.33 ** |

| Cyber. Victim. → Expression | χ2 (643) = 2385.9; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 4.03/1 | −0.22 * | 0.15 |

| Cyber. Victim. → Control | χ2 (643) = 2384.7; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 2.58/1 | −0.39 ** | 0.23 * |

| Other-emotion → Absences | χ2 (643) = 2381.5; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.03/1 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Other-emotion → Offenses | χ2 (643) = 2381.1; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.63/1 | 0.28 ** | 0.16 |

| Other-emotion → Life Quality | χ2 (643) = 2385.3; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 3.44/1 | −0.18 * | 0.20 * |

| Other-emotion → GPA | χ2 (643) = 2382.1; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.31/1 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Self-emotion → Absences | χ2 (643) = 2383.8; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 2.01/1 | 0.41 *** | −0.15 * |

| Self-emotion → Offenses | χ2 (643) = 2381.1; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.74/1 | 0.19 * | 0.05 |

| Self-emotion → Life Quality | χ2 (643) = 2382.1; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.23/1 | 0.24 * | 0.39 ** |

| Self-emotion → GPA | χ2 (643) = 2382.2; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.32/1 | 0.10 | 0.23 * |

| Expression → Absences | χ2 (643) = 2382.1; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.39/1 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Expression → Offenses | χ2 (643) = 2382.0; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.35/1 | 0.32 * | 0.22 * |

| Expression → Life Quality | χ2 (643) = 2382.0; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.31/1 | 0.21 * | 0.31 ** |

| Expression → GPA | χ2 (643) = 2384.6; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 2.70/1 | −0.21 * | 0.04 |

| Control → Absences | χ2 (643) = 2381.1; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 0.07/1 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| Control → Offenses | χ2 (643) = 2385.6; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 3.71/1 | 0.12 | −0.20 * |

| Control → Life Quality | χ2 (643) = 2384.3; C = 0.91, R = 0.07, S = 0.07 | 2.46/1 | −0.27 ** | 0.29 ** |

| Control → GPA | χ2 (643) = 2380.5; C = 0.92, R = 0.06, S = 0.07 | 1.22/1 | 0.02 | 0.25 * |

| Moderating Effects | Non-Spectatorship Group (NSG) | Spectatorship-Adherent Group (SG) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | β | SE | p-Value | β | SE | p-Value | |

| From Cyber. Victimization to Emotion Management | |||||||

| Cyber. Victimization → Other-emotion Appraisal | −0.40 *** | 0.27 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.48 | |

| Cyber. Victimization → Self-emotion Appraisal | −0.33 ** | 0.24 | 0.003 | 0.33 ** | 0.20 | 0.004 | |

| Cyber. Victimization → Emotion Expression | −0.22 * | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.14 | |

| Cyber. Victimization → Emotion Control | −0.39 ** | 0.25 | 0.001 | 0.23 * | 0.35 | 0.02 | |

| From Other-emotion Appraisal to DVs | |||||||

| Other-emotion Appraisal → Absences | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.68 | |

| Other-emotion Appraisal → School-related Offenses | 0.28 ** | 0.19 | 0.009 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.09 | |

| Other-emotion Appraisal → Health-related Quality of Life | −0.18 * | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.20 * | 0.21 | 0.03 | |

| Other-emotion Appraisal → GPA | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.67 | |

| From Self-emotion Appraisal to DVs | |||||||

| Self-emotion Appraisal → Absences | 0.41 *** | 0.25 | <0.001 | −0.15 * | 0.18 | 0.04 | |

| Self-emotion Appraisal → School-related Offenses | 0.19 * | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.59 | |

| Self-emotion Appraisal → Health-related Quality of Life | 0.24 * | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.39 ** | 0.25 | 0.001 | |

| Self-emotion Appraisal → GPA | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.23 * | 0.13 | 0.01 | |

| From Emotion Expression to DVs | |||||||

| Emotion Expression → Absences | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.92 | 0.12 | 0.43 | 0.29 | |

| Emotion Expression → School-related Offenses | 0.32 * | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.22 * | 0.17 | 0.02 | |

| Emotion Expression → Health-related Quality of Life | 0.21 * | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.31 ** | 0.26 | 0.006 | |

| Emotion Expression → GPA | −0.21 * | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.57 | |

| From Emotion Control to DVs | |||||||

| Emotion Control → Absences | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.25 | |

| Emotion Control → School-related Offenses | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.37 | −0.20 * | 0.32 | 0.02 | |

| Emotion Control → Health-related Quality of Life | −0.27 ** | 0.16 | 0.005 | 0.29 ** | 0.26 | 0.002 | |

| Emotion Control → GPA | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.25 * | 0.33 | 0.03 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, I.; Chang, Y.; Yoo, T.; Plunkett, E. Cracking the Code of Cyberbullying Effects: The Spectator Sports Solution for Emotion Management and Well-Being Among Economically Disadvantaged Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040555

Lee I, Chang Y, Yoo T, Plunkett E. Cracking the Code of Cyberbullying Effects: The Spectator Sports Solution for Emotion Management and Well-Being Among Economically Disadvantaged Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):555. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040555

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ilrang, Yonghwan Chang, Taewoong Yoo, and Emily Plunkett. 2025. "Cracking the Code of Cyberbullying Effects: The Spectator Sports Solution for Emotion Management and Well-Being Among Economically Disadvantaged Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040555

APA StyleLee, I., Chang, Y., Yoo, T., & Plunkett, E. (2025). Cracking the Code of Cyberbullying Effects: The Spectator Sports Solution for Emotion Management and Well-Being Among Economically Disadvantaged Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040555