Violence Against Administrators: The Roles of Student, School, and Community Strengths and Cultural Pluralism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Student Strengths

1.1.2. School Strengths

1.1.3. Community Strengths

1.2. School Cultural Pluralism

1.3. Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Ecological Strengths and Problems Scale

2.2.2. Administrator Victimization

2.2.3. School Cultural Pluralism

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Rates of Violence

3.2. Demographic Differences in Administrator Victimization

3.3. Initial Model Results with Main Effects Only (No Moderation)

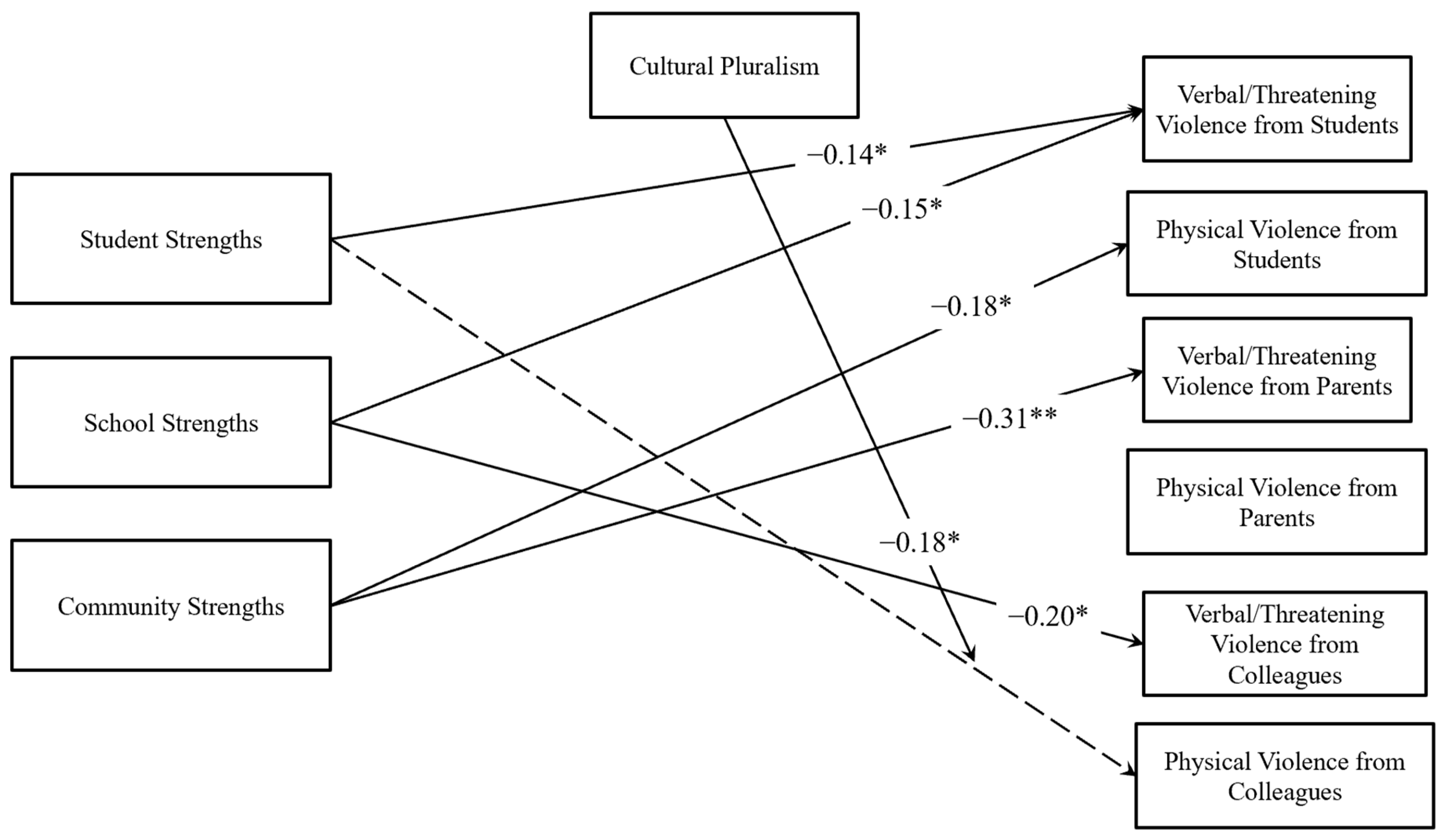

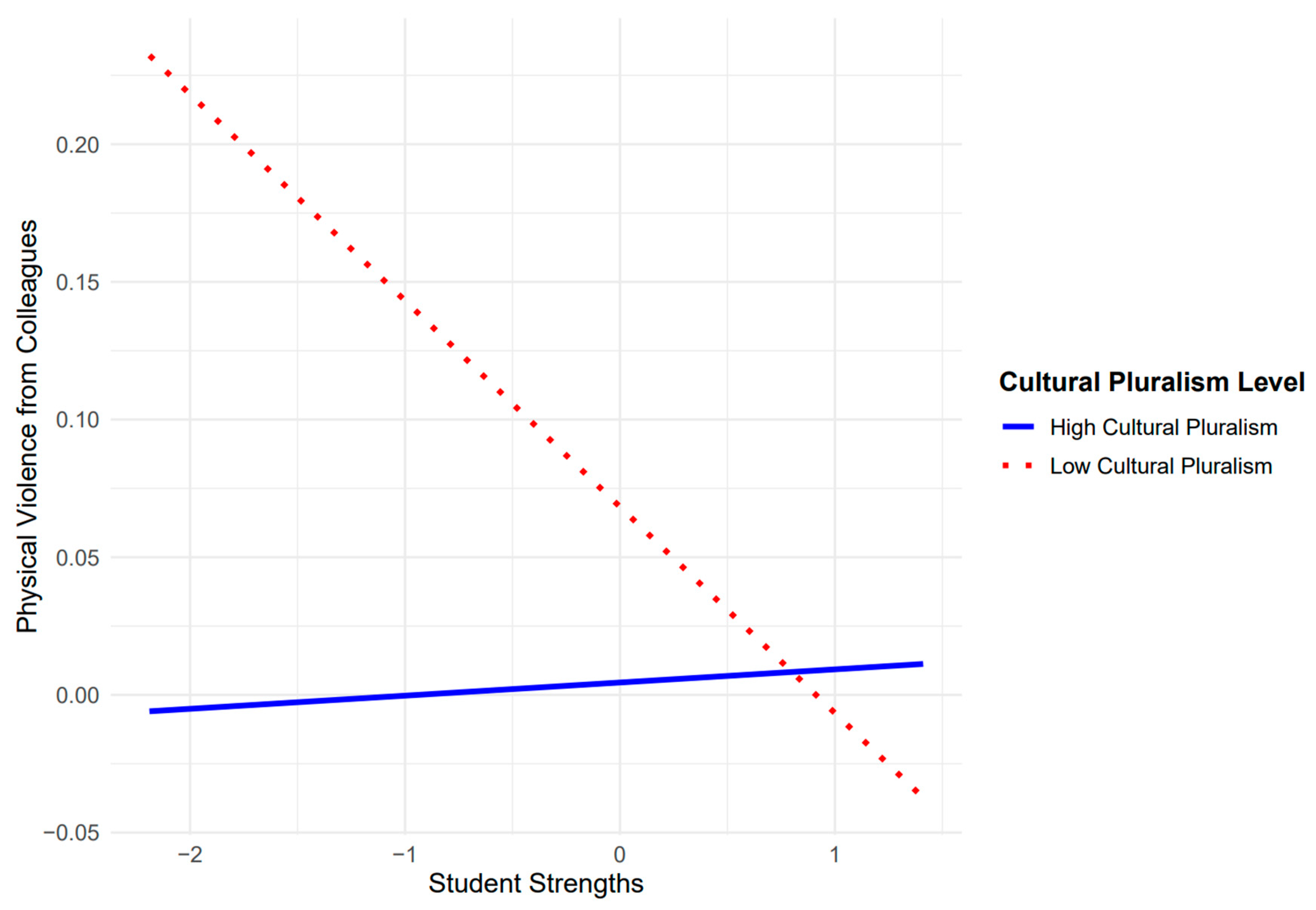

3.4. Model Results with Cultural Pluralism Practices Moderator

4. Discussion

4.1. To What Extent Does Administrator Victimization Vary by Individual, School, and Community Characteristics?

4.2. Are Student, School, and Community Strengths Associated with Administrator Victimization?

4.3. Does Cultural Pluralism Moderate the Relation Between Ecological Strengths and Administrator Victimization?

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, B., Rahimi, M., Horwood, M., & Riley, P. (2022). The New Zealand secondary principal occupational health, safety and wellbeing survey: 2021 data. Research for Educational Impact (REDI). Deakin University. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, B., Rahimi, M., & Riley, P. (2021). Offensive behaviours against school leaders: Prevalence, perpetrators and mediators in Australian government schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(3), 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2019). Bullying, school violence, and climate in evolving. Contexts: Culture, organization, and time. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bardach, L., Yanagida, T., Gradinger, P., & Strohmeier, D. (2022). Understanding for which students and classes a socio-ecological aggression prevention program works best: Testing individual student and class level moderators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(2), 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J. K., & Cornell, D. (2016). Authoritative school climate, aggression toward teachers, and teacher distress in middle school. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(1), 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, R. J. (2015). Cultural pluralism. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 41(4–5), 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, R., & Zwane, R. P. (2021). Strategies to prevent learner-on-educator violence in South African schools. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 20(9), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, C., & Jenkins, L. N. (2018). Teacher-directed violence and stress: The role of school setting. Contemporary School Psychology, 22(4), 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C. P., Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., & Nation, M. (2021). Addressing school safety through comprehensive school climate approaches. School Psychology Review, 50(2), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals. (Working Paper No. 17803). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S., Felner, R. D., Seitsinger, A., Burns, A., & Bolton, N. (2008). A large-scale study of the assessment of the social environment of middle and secondary schools. Journal of School Psychology, 46(5), 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1976). The experimental ecology of education. Educational Researcher, 5(9), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookmeyer, K. A., Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: A multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capp, G., Astor, R. A., & Gilreath, T. D. (2020). Advancing a conceptual and empirical model of school climate for school staff in California. Journal of School Violence, 19(2), 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C., & Burns, R. (2022). School culture, racial composition, and preventing violence: Evaluating punitive and supportive responses to improving safety. Social Sciences, 11(7), 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., & Martin, A. J. (2020). School principals’ workplace well-being: A multination examination of the role of their job resources and job demands. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(4), 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté-Lussier, C., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2016). Feelings of safety at school, socioemotional functioning, and classroom engagement. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(5), 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cordova, F., Berlanda, S., Pedrazza, M., & Fraizzoli, M. (2019). Violence at school and the well-being of teachers. The importance of positive relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D. E., Reyes, P., Carrola, P., Edwards, W., & James, L. (2021). Novice principal burnout: Exploring secondary trauma, working conditions, and coping strategies in an urban district. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 22, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T., Kidson, P., & Marsh, H. (2024). The Australian principal occupational health, safety and wellbeing survey (IPPE report). Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University. Available online: https://www.acu.edu.au/about-acu/news/2024/march/violence-escalates-and-mental-health-suffers-but-principals-remain-resilient (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Diliberti, M. K., & Schwartz, H. L. (2023). Educator turnover has markedly increased, but districts have taken actions to boost teacher ranks: Selected findings from the sixth American school district panel survey. RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Downer, J. T., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). How do classroom conditions and children’s risk for school problems contribute to children’s behavioral engagement in learning? School Psychology Review, 36(3), 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B. W., Viano, S., Curran, F. C., Pearman, F. A., & Gardella, J. H. (2018). Students’ feelings of safety, exposure to violence and victimization, and authoritative school climate. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(1), 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, G. D., Gottfredson, D. C., Payne, A. A., & Gottfredson, N. C. (2005). School climate predictors of school disorder. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42(4), 412–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation. Available online: http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Huang, F., & Anyon, Y. (2020). The relationship between school disciplinary resolutions with school climate and attitudes toward school. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 64(3), 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F. L., Eddy, C. L., & Camp, E. (2017). The role of perceptions of school climate and teacher victimization by students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23–24), 5526–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. L. (2009). Improving the school environment to reduce school violence: A review of the literature. Journal of School Health, 79(10), 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapa, R. R., Luke, J., Moulthrop, D., & Gimbert, B. (2018). Teacher victimization in authoritative school environments. Journal of School Health, 88(4), 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J. H., Diliberti, M. K., & Hamilton, L. S. (2022). How principals’ perceived resource needs and job demands are related to their dissatisfaction and intention to leave their schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. AERA Open, 8(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Ko, Y. (2022). Perceived discrimination and workplace violence among school health teachers: Relationship with school organizational climate. Research in Community and Public Health Nursing, 33(4), 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A., & Smith, J. D. (2022). Peer aggression and conflictual teacher-student relationships: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. N., & Johansen, S. (2011). The relationship between school multiculturalism and interpersonal violence: An exploratory study. Journal of School Health, 81, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesneskie, E., & Block, S. (2017). School violence: The role of parental and community involvement. Journal of School Violence, 16(4), 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom Johnson, S., Waasdorp, T. E., Cash, A. H., Debnam, K. J., Milam, A. J., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2017). Assessing the association between observed school disorganization and school violence: Implications for school climate interventions. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Martinez, A., & McMahon, S. D. (2019). Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 9(5), 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, F., & Jenkins, L. (2010). Schools as sites of race relations and intercultural tension. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(10), 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S. D., Cafaro, C. L., Bare, K., Zinter, K. E., Murillo, Y. G., Lynch, G., Anderman, E. M., Espelage, D. L., Reddy, L. A., & Subotnik, R. (2022b). Rates and types of student aggression against teachers: A comparative analysis of U.S. elementary, middle, and high schools. Social Psychology of Education, 25, 767–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S. D., Martinez, A., Espelage, D., Rose, C., Reddy, L. A., Lane, K., Anderman, E. M., Reynolds, C. R., Jones, A., & Brown, V. (2014). Violence directed against teachers: Results from a national survey. Psychology in the Schools, 51, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S. D., Reddy, L. A., Worrell, F. C., Anderman, E. M., Astor, R. A., Espelage, D., & Martinez, A. (2025). Ecological strengths and problems scale [unpublished scale]. Department of Psychology, DePaul University. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, S. D., Worrell, F. C., Reddy, L. A., Martinez, A., Espelage, D. L., Astor, R. A., Anderman, E. M., Valido, A., Swenski, T., Perry, A. H., Dudek, C. M., & Bare, K. (2024). Violence and aggression against educators and school personnel, retention, stress, and training needs: National survey results. American Psychologist, 79, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP). (2021). NASSP survey signals a looming mass exodus of principals from schools. NASSP. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP). (2023, June 20). NASSP survey of principals and students reveals the extent of challenges facing schools. Available online: https://www.nassp.org/news/nassp-survey-of-principals-and-students-reveals-the-extent-of-challenges-facing-schools/ (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2023a). Characteristics of public and private school principals. Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cls (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2023b). Teachers threatened with injury or physically attacked by students. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/a05/teacher-attacked-by-students (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Perry, A. H., Reddy, L. A., Martinez, A., McMahon, S. D., Anderman, E. M., Astor, R. A., Espelage, D. L., Worrell, F. C., Swenski, T., Bare, K., Dudek, C. M., Hunt, J., Calvit, A. I. M., Lee, H. J., & Liu, X. (2024). Administrator turnover: The roles of district support, safety, anxiety, and violence from students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, P. (2015). Irish principals & deputy principals occupational health, safety & wellbeing survey. Australian Catholic University. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, P. (2018). The Australian principal occupational health, safety and wellbeing survey: 2017 data. Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J., Kahne, J., Ishimoto, M., Kwako, A., Stern, S. C., Bingener, C., Raphael, L., Alkam, S., & Conde, Y. (2022). Educating for a diverse democracy: The chilling role of political conflict in blue, purple, and red communities. UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access. [Google Scholar]

- Schachner, M. K., Noack, P., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Eckstein, K. (2016). Cultural diversity climate and psychological adjustment at school—Equality and inclusion versus cultural pluralism. Child Development, 87, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, J., Allensworth, E., & Huang, H. (2016). The role of teacher leadership in how principals influence classroom instruction and student learning. American Journal of Education, 123, 69–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. V., Wang, M.-T., & Hill, D. J. (2020). Black youths’ perceptions of school cultural pluralism, school climate and the mediating role of racial identity. Journal of School Psychology, 83, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogunro, O. A. (2012). Stress in school administration: Coping tips for principals. Journal of School Leadership, 22, 664–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Qian, X., & Goodnight, B. (2019). Examining the roles of parents and community involvement and prevention programs in reducing school violence. Journal of School Violence, 18(3), 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E. D., Doan, S., Woo, A., Gittens, A. D., Lawrence, R. A., Berdie, L., Wolfe, R. L., Greer, L., & Schwartz, H. L. (2022). Restoring teacher and principal well-being is an essential step for rebuilding schools: Findings from the State of the American Teacher and State of the American Principal surveys. RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Swearer, S. M., Lembeck, P., Collins, A., & Berry, B. (2015). Teachers matter: An examination of student-teacher relationships, attitudes toward bullying, and bullying behavior. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C., Gerberich, S. G., Alexander, B. H., Ryan, A. D., Nachreiner, N. M., & Mongin, S. J. (2013). Work-related violence against educators in Minnesota: Rates and risks based on hours exposed. Journal of Safety Research, 44, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, W. N. (2003). Individual and institutional predictors of school disorder. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 1, 346–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Sharkey, J. D., Reed, L. A., Chen, C., & Dowdy, E. (2018). Bullying victimization and student engagement in elementary, middle, and high schools: Moderating role of school climate. School Psychology Quarterly, 33, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Qin, L., & Ning, L. (2021). School violence and teacher professional engagement: A cross-national study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 628809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulauf-McCurdy, C. A., & Zinsser, K. M. (2022). A qualitative examination of the parent–teacher relationship and early childhood expulsion: Capturing the voices of parents and teachers. Infants & Young Children, 35(1), 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Student strengths | 2.39 | 0.89 | - | |||||||||

| 2. School strengths | 3.18 | 1.00 | 0.56 ** | - | ||||||||

| 3. Community strengths | 2.86 | 0.79 | 0.60 ** | 0.69 ** | - | |||||||

| 4. Cultural pluralism | 3.70 | 0.74 | 0.35 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.44 ** | - | ||||||

| 5. Verbal/threatening violence from students | 0.55 | 0.71 | −0.32 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.23 ** | - | |||||

| 6. Physical violence from students | 0.61 | 0.93 | −0.08 | −0.16 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.11 * | 0.54 ** | - | ||||

| 7. Verbal/threatening violence from parents | 0.69 | 0.68 | −0.16 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.43 ** | - | |||

| 8. Physical violence from parents | 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.21 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.38 ** | - | ||

| 9. Verbal/threatening violence from colleagues | 0.16 | 0.39 | −0.06 | −0.16 ** | −0.10 | −0.11 * | 0.30 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.41 ** | - | |

| 10. Physical violence from colleagues | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.003 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.15 ** | 0.10 | 0.19 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.50 ** | - |

| DV: Verbal/threatening violence from students | β | SE | p |

| Student strengths | −0.14 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| School strengths | −0.15 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Community strengths | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.37 |

| Cultural pluralism | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.55 |

| Student strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.21 |

| School strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| Community strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| DV: Physical violence from students | |||

| Student strengths | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| School strengths | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.37 |

| Community strengths | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Cultural pluralism | −0.002 | 0.07 | 0.97 |

| Student strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.56 |

| School strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.30 |

| Community strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| DV: Verbal/threatening violence from parents | |||

| Student strengths | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.28 |

| School strengths | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.83 |

| Community strengths | −0.31 | 0.08 | <0.01 |

| Cultural pluralism | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| Student strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.11 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

| School strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Community strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.89 |

| DV: Physical violence from parents | |||

| Student strengths | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.22 |

| School strengths | −0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Community strengths | 0.002 | 0.09 | 0.98 |

| Cultural pluralism | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.65 |

| Student strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.11 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| School strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.88 |

| Community strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.002 | 0.09 | 0.99 |

| DV: Verbal/threatening violence from colleagues | |||

| Student strengths | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| School strengths | −0.20 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Community strengths | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.88 |

| Cultural pluralism | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.69 |

| Student strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.10 | 0.09 | 0.25 |

| School strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Community strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.95 |

| DV: Physical violence from colleagues | |||

| Student strengths | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| School strengths | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| Community strengths | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.59 |

| Cultural pluralism | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.58 |

| Student strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.18 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| School strengths × cultural pluralism | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.63 |

| Community strengths × cultural pluralism | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McMahon, S.D.; Perry, A.H.; Swenski, T.; Bare, K.; Hunt, J.; Martinez, A.; Reddy, L.A.; Anderman, E.M.; Astor, R.A.; Espelage, D.L.; et al. Violence Against Administrators: The Roles of Student, School, and Community Strengths and Cultural Pluralism. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040556

McMahon SD, Perry AH, Swenski T, Bare K, Hunt J, Martinez A, Reddy LA, Anderman EM, Astor RA, Espelage DL, et al. Violence Against Administrators: The Roles of Student, School, and Community Strengths and Cultural Pluralism. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040556

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcMahon, Susan D., Andrew H. Perry, Taylor Swenski, Kailyn Bare, Jared Hunt, Andrew Martinez, Linda A. Reddy, Eric M. Anderman, Ron Avi Astor, Dorothy L. Espelage, and et al. 2025. "Violence Against Administrators: The Roles of Student, School, and Community Strengths and Cultural Pluralism" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040556

APA StyleMcMahon, S. D., Perry, A. H., Swenski, T., Bare, K., Hunt, J., Martinez, A., Reddy, L. A., Anderman, E. M., Astor, R. A., Espelage, D. L., Worrell, F. C., & Dudek, C. M. (2025). Violence Against Administrators: The Roles of Student, School, and Community Strengths and Cultural Pluralism. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040556