1. Introduction

At the start of the 21st century, academic literature identified the ‘‘black box’’ in leadership and employee performance. Nonetheless, the present circumstance has changed as various studies currently address this issue, giving evidence of employee performance-related factors (such as organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, employee satisfaction, etc.) as mediating factors that clarify the impact of leadership on employee performance (

Harwiki 2016;

Setyaningrum et al. 2017). Large numbers of these investigations consider employee performance as the reliant variable since this is a key proximal result reflecting practices heavily influenced by employees and assisting in accomplishing organizational objectives/goals.

Leadership is a component that extensively affects the proficiency of employees and managers (

Buil et al. 2019;

Iqbal et al. 2015). The leadership styles and employee performance had a causal connection towards the achievement of an association, depending on the different behavioral variables. It came about that leadership and performance have both immediate and intersectional relationships (

Vigoda-Gadot 2007). Servant leadership can significantly improve employee performance and would help to make exceptional progress and success (

Setyaningrum and Pawar 2020). Consequently, the research studies additionally presume that organizations need to focus on leadership style to improve employee performance (

Tripathi et al. 2020).

Ekhsan and Aziz (

2021) clarified the use of the partial least square (PLS) model, which means that servant leadership can assume a noticeable part in boosting employee performance.

Instances of pneumonia diagnosed with a vague reason were recorded by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Wuhan, China, on 31 December 2019. On 7 January 2020, the Chinese specialists tracked down a new COVID virus, allegedly called “2019-nCoV”. COVID (CoV) incorporates a broad scope of infections that cause sicknesses from colds to more outrageous conditions. Once more, the new strain, which was not recently recognized in people, addresses a novel COVID (nCoV). The new infection was subsequently called the “Coronavirus infection” (

World Health Organisation 2020). Virtually every country on the planet, including Pakistan, was influenced by COVID-19. The principal COVID-19 case was detected in Pakistan in Karachi on February 26, 2020. Its quick spread was inconceivably concerning. In light of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) measurements, around 215 countries, like Pakistan, were influenced by this virus. While thinking about everyday factual information on the number of episodes, the spread of COVID-19 in Pakistan was created.

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, many organizations lessened employee compensation or fired their employees to maintain financial stability (

Almeida and Santos 2020). Then, at that point, many occupation openings were shut because numerous businesses went bankrupt. These things affected the employee’s aims to leave their organization (

Baum et al. 2020). Individuals continued to have adverse reactions to survive in the COVID-19 pandemic circumstances (COVID). Important things were how they and their family stayed healthy, while not being pressured, and meeting their daily needs (COVID). Leadership style truly helps to make the workplace ideal in articulating the excellence of the vision and in increasing the performance of the employee and the organization (

Yanney 2014). Managers are encouraged to reliably work on viable correspondence and cooperation competency (

Hidayat et al. 2021).

The extreme changes influenced employee emotions (

Leyer et al. 2021). The critical issue is the way to deal with the feelings that emerge into sound energy for the organization’s advantage. The services of organizations that are going through changes need to screen the degree of employee job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is essentially identified with the degree of services and the employee’s performance (

Charalambous et al. 2018). During the time spent on changes, the company needs change-situated services. It is an essential factor in deciding the accomplishment of progress. The leaders’ ability is tested from the start of the cycle, starting from empowering steps and initiating change, to making continuous improvements by assessing and changing the work interaction to be more versatile, and especially reassuring development all through the cycle since it is demonstrated to positively impact on work performance (

Mikkelsen and Olsen 2019).

Despite the pertinence of the previously mentioned commitments, empirical investigations in the literature mediating and moderating the role of the individual variables in the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance are divided in terms of theories and points of view, which involves the testing of explicit interceding and directing factors (the leader’s gender, organizational commitment, and self-esteem), yet not in others (

Lemoine and Blum 2021;

Setyaningrum et al. 2017;

Xiongying and Boku 2021). Without a doubt, few examinations have considered a few mediating factors, which makes it hard to acquire a more extensive perspective on these transitional mechanisms.

Focusing on servant leadership needs to receive further legitimacy compared to mainstream leadership theory.

Chiniara and Bentein (

2018) encourage researchers to investigate the impact of servant leadership, as well as individual outcomes such as individual performance or employee performance.

Better employee performance management is imperative to enhance organizational performance and effectiveness (

Stanton and Pham 2014). Different methodologies are used to examine the employee performance variable, e.g.,

Delmas and Pekovic (

2018) used a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) methodology to see how employee performance considers employee productivity. A case study on the Bonjus and Khatib & Alami companies show the impact of the training given to the employee, which increases their performance on the job and increases the company’s overall performance (

Halawi and Haydar 2018).

Ponta et al. (

2020) studied public administration (PA) to address monetary incentives, and their impact on employees’ performance. As the study was conducted in Italy, where the stimulus is given according to the performance of the employee, a positive and significant impact was found in the short, middle, and long term. Research on both transactional and transformational leadership studied employee performance and shows a more significant relation, but are more linked with transformational leadership (

Paracha et al. 2012).

As mentioned before, previous research is enriched with group performance or team performance, and individual outcomes are focused on comparatively less. Further, individuals having differences in personality traits and personality values could also constitute influential moderators. Therefore,

Sun and Shang (

2019) respond to the call of

Liden et al. (

2014b) by examining the individual characteristics of servant leadership. Further research suggests that it is necessary for future studies to incorporate personal characteristics and personality values, thereby empowering researchers to assemble a total nomological net for understanding servant leadership. Current research will fill the gap between the personality values on servant leadership style and employee performance.

Commercial banks in Pakistan offer financial help to the general populace and businesses, ensuring monetary and socially consistent quality and the attainable advancement of the economy; notwithstanding, business banks are not confined to local financial services. Commercial banking has gone through significant changes in recent times. There were dramatic administrative changes, the expansion and reconciliation of worldwide monetary business sectors, and markets and establishments have opened new doors and difficulties for commercial banking. These regulatory changes enable commercial banks to service many kinds of financial market activity. The banking system plays a crucial role in the Pakistani financial system (

Ali et al. 2021). The working environment of Pakistani banking sectors saw substantial transformations during the past two decades. In recent years, Pakistani banks have moved their financing from the government to the private sector. Pakistan’s financial industry is going through several changes. New organizations, for example, are buying out Pakistani businesses of several international banks. As a result, the number of listed banks is growing (

Saad et al. 2021). These transformation events have an impact on the banking sector’s profitability drivers. Pakistan’s banking industry is the third most significant contributor to the country’s economy. The services sector contributed more than half of the economy’s GDP. At the end of 2020, the banking sector had a rate of 18.6%, far over the required 11.5%. The COVID-19 epidemic threw the economy into disarray, and the financial industry is still struggling to get back on track (

Zhiqiang et al. 2021). In such a situation, enhancing employee performance enhances organizational performance (

Saleh et al. 2020).

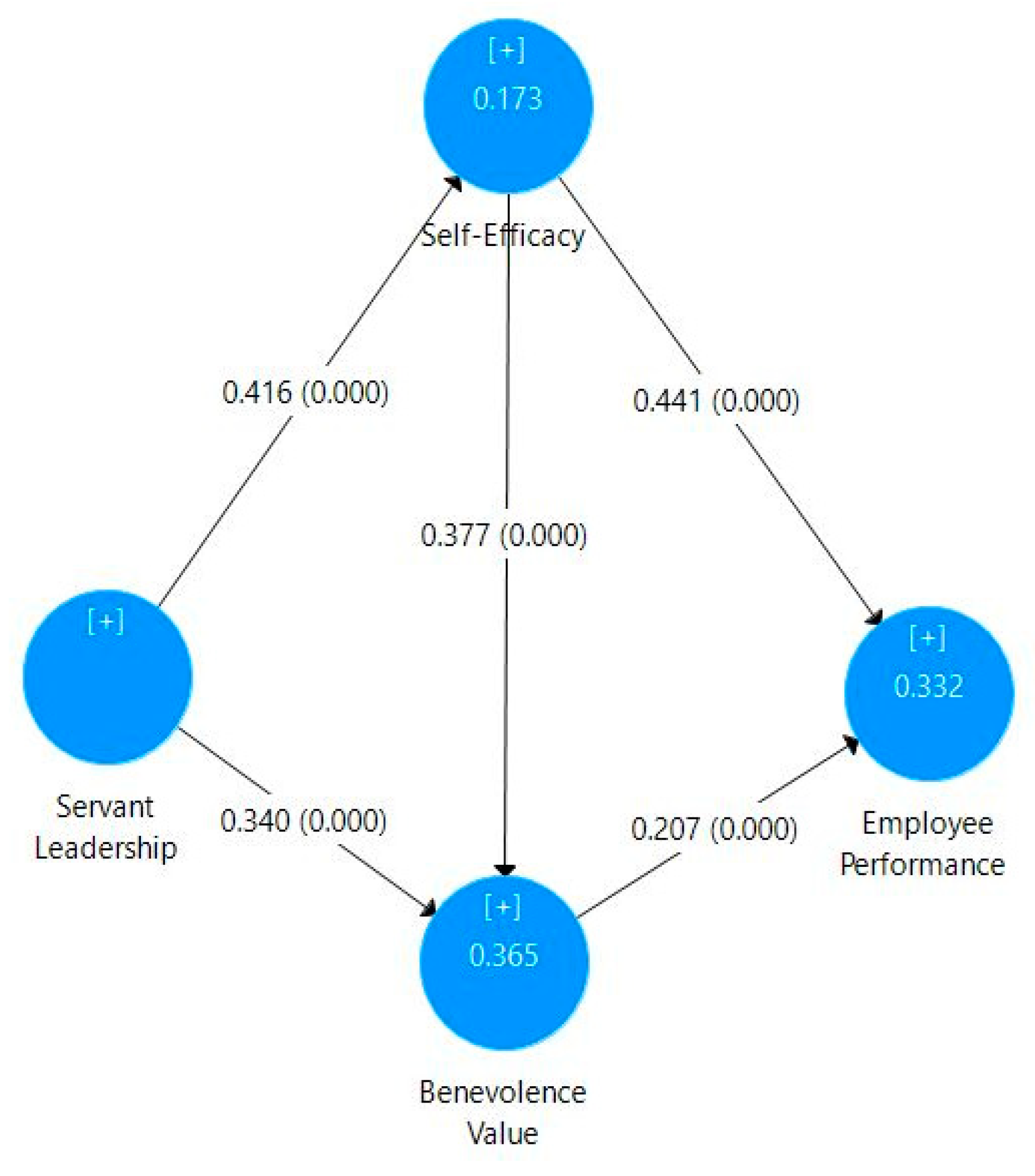

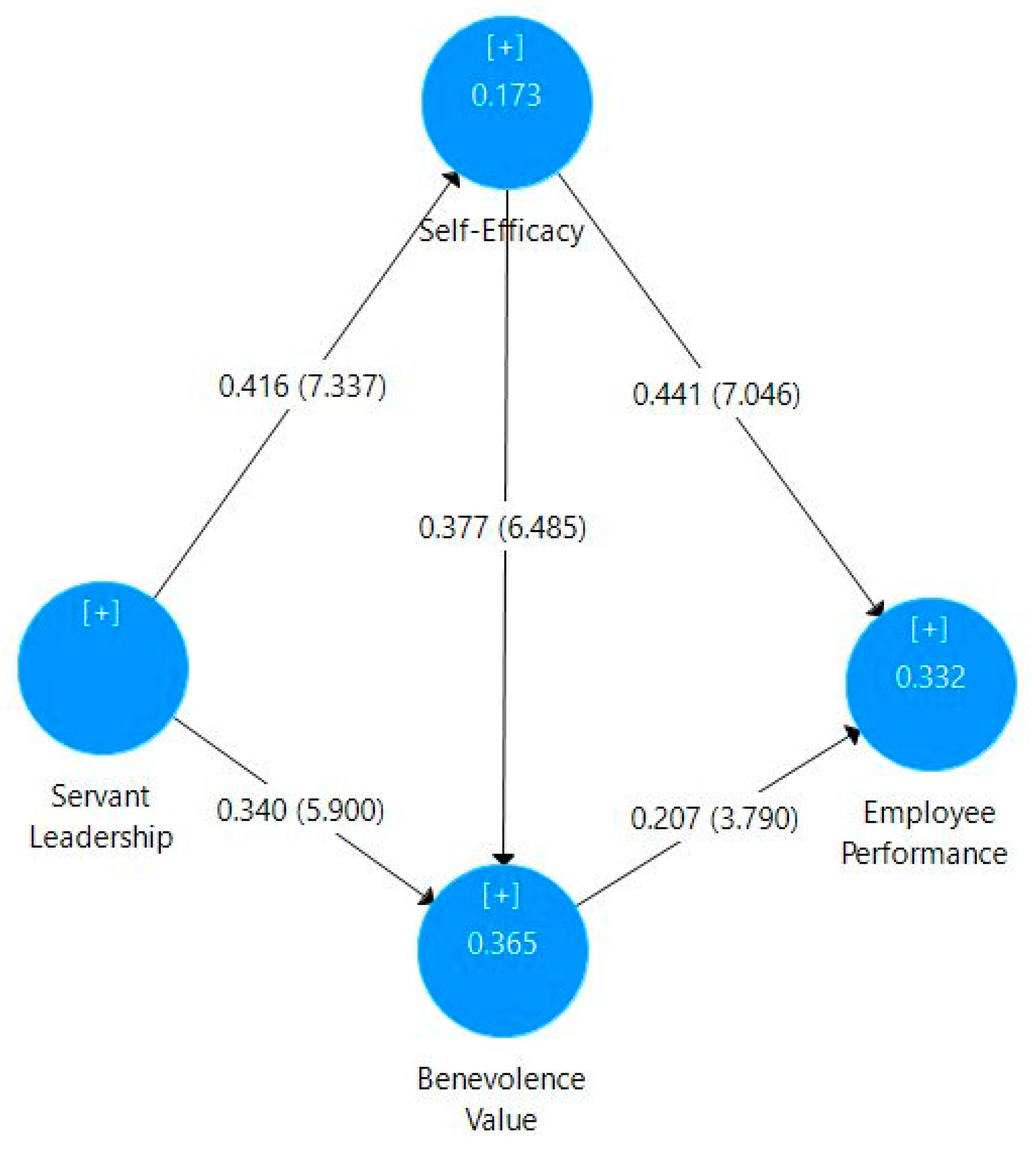

The paper is organized as follows. The first section provides an introduction, followed by research significance and objectives. The following research model (see

Figure 1) based on the theoretical foundation is discussed. The second section discusses the literature on each variable, e.g., employee performance, servant leadership, employees’ self-efficacy, benevolence values, and proposed hypotheses. The development of the hypotheses is followed by the research methods. Last but not least, data analysis and the interpretation of results are explained. Lastly, this paper discusses findings and limitations.

1.1. Research Significance

Research studies contribute to theoretical and managerial implications. From the theoretical ramifications’ point of view, earlier examinations have researched the role of rewards, organizational culture, employee prosocial motivation as mediating, and religiosity as moderating pathways through which servant leadership affects employee performance (

Abbas et al. 2020;

Sihombing et al. 2018;

Stollberger et al. 2019). This examination theoretically adds to the prospering literature on servant leadership by empirically testing the fundamental mediating mechanism of leaders’ benevolence values and employee self-efficacy in the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

The vital takeaway of this investigation for leaders is that they ought to understand that their remarkable leadership style in the work environment influences employee performance. Leaders can use their leadership style in improving organizational performance and employee performance. Moreover, this research brings important theoretical and practical implications for financial industry experts and behavioral researchers.

1.2. Research Objectives

- ▪

To test the indirect effects of self-efficacy on the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

- ▪

To test the indirect effects of benevolence values on the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

- ▪

To test the serial mediation of self-efficacy and benevolence values on the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

1.3. Research Model and Theoretical Foundation

The purpose of the research model is to outline the critical relationships between study variables and represent the primary research idea. The current research model comprises four crucial constructs as follows: (1) employee performance as regressing variable, (2) servant leadership as regressors variable, (3) self-efficacy, and (4) benevolence value intervening variable (see

Figure 1).

Social identity theory (

Tajfel 1978) explains that servant leaders consider subordinates a crucial part of the organization and focus on building an authentic bond. The employee needs to recognize their self-identify and engage in behavior that will ultimately increase the individual, team and organizational worth (

Chen et al. 2015). Moreover, it positively impacts followers’ identification and employee voice (

Chughtai 2016) and reduces servant leaders’ burnout (

Rivkin et al. 2014), and enhances organizational citizenship behavior OCB (

Yoshida et al. 2014). Behavioral theories, e.g., social exchange theory and social learning theory, have provided an essential base for conceptualizing servant leadership, and they can enable leaders to transform their followers’ behavior. Building the argument based on the work of

Greenleaf (

1991), servant leaders are more inclined towards modifying their follower’s behavior. Researchers have contended that leaders have a significant impact on their supporters, altering devotees’ mindsets and practices.

2. Literature Review on Study Variables

This section reviews the literature on endogenous variables, including (i) employee performance, and their three dimensions, e.g., task performance, contextual performance, and adaptive performance. Next, (ii) servant leadership as exogenous variable, (iii) self-efficacy, and (iv) benevolence value as endogenous mediating variables.

2.1. Employee Performance

Performance is an individual’s general result or accomplishment during express events of responsibility that stand apart from the work norm. The literature on performance consists of both contrary and supportive evidence, but significant progress has made in this regard as well (

Zainal 2004). Zainal further concludes that performance does not stand in isolation in connection with work fulfillment and pay, but is also affected by various antecedents, including individual characteristics. Employee performance (EP) is directed by the limit, need, and condition. EP is linked with progression, and these associations are most likely required for successful people or high achievers’ laborers.

EP is vital in deciding the accomplishment of organizational objectives and missions. Consequently, companies search for approaches to motivate workers and improve their performance at work. However, EP has been thoroughly investigated in the western context. However, there has been very little research exists on measuring EP, such as contextual performance adaptative performance and task performance in the Pakistani context. Significant management literature suggests that EP can be predicted by various antecedents (

Ali et al. 2020;

Khushk and Works 2019;

Yan et al. 2020).

Over decades, EP has been explored in various settings across the world in different industries and societies to enhance existing practices, ideas, in achieving ideal solutions (

Bono and Judge 2003). Integrating findings on best practices can improve performance and empower organizations to utilize resources for workers’ physical, psychological betterment, to enhance their enthusiastic capacities (

Pham-Thai et al. 2018). Innovative practices like (IWB) (

Pham-Thai et al. 2018), personal and group learning positively contribute to job performance (

Sun et al. 2017), and enhance OCB (

Hermawati and Mas 2017), and the relationship between leader and followers based on leader member exchange (LMX) Theory. (

Zhang and Bartol 2010) have critically discussed direct and indirect factors that are drawing in academic consideration for advancing hierarchical effectiveness, execution, and development. Various research surveys have been conducted on employee performance and the defining factors in academic literature. These surveys primarily concentrate on job demand, assets and stressors (

Pandey 2019), and mobile-banking, respectively (

Tam and Oliveira 2017). In the current research, the employee performance is measured with three dimensions, including task performance, contextual performance, and adaptive performance.

2.1.1. Task Performance

Task performance (TP) is defined as “the proficiency with which job incumbents perform activities that are formally recognized as part of their jobs; activities that contribute to the organization’s technical core either directly by implementing a part of its technological process, or indirectly by providing it with needed materials or services”(73) (

Borman and Motowidlo 1993). TP is the capability with which officeholders perform tasks that are officially perceived as a component of their positions, exercises that add either directly or indirectly to an organization.

Budhwar and Chandrakumara (

2007), on the other hand, conclude that worker TP includes activities that are part of the conventional expected set of responsibilities. In this way, it implies work explicit undertaking capability, specialized capability, or in-job performance.

2.1.2. Contextual Performance

The origin point of contextual performance (CP) can be followed back to the research of

Brief and Motowidlo (

1986), who introduced the possibility of significant prosocial behavior in organizations.

Borman and Motowidlo (

1993), describe CP as discretionary behaviors that apply across all jobs, are not necessarily role prescribed, and that contribute to the social and psychological environment of the organization.

Campbell (

1990) has proposed that task execution can be divided into two separate classifications (i) task performance and (ii) contextual performance. CP refers to those practices that establish work and related with the creation supportive climate, such as involving in extra or difficult work, keeping up excitement at work, helping out others and sharing data and other basic resources. Contextual activities can be part of all basic positions and are less job recommended in most cases. These activities support the hierarchical, social, and mental climate in which task performances are conducted. It also includes behaviors such as volunteering, helping, persisting, etc., that are more likely anticipated by volitional factors identified with singular contrasts in persuasive qualities and inclination or individual organization fit.

2.1.3. Adaptive Performance

Adaptive performance (AP) can be discussed based on various definitions, viewpoints and conceptualizations (

Baard et al. 2014).

Jundt et al. (

2015) have provided better understanding and describes AP as conduct coordinated effort of task performance that result in changes an influence work-related outcomes. According to

Johnson (

2001), AP is an individual’s ability to adjust him/herself in a constantly changing work environment by modifying conduct, accepting new and innovative situations. Similarly,

Griffin et al. (

2007) have tried to link adaptive performance with training in the workplace. Likewise,

Charbonnier-Voirin and Roussel (

2012) have declared that individuals need the capacity and status to include themselves in learning new skills. AP alters an individual attitude and behavior to address the hierarchical change, and it happens essentially through adjusting to the new work requirements.

2.2. Servant Leadership

Previous literature has thoughtfully recognized servant leadership (SL) from different leadership styles, e.g., transformational leadership (

Barbuto and Wheeler 2006;

Stone et al. 2004).

Van Dierendonck (

2011) has presented this view in his work that servant leadership varies from the other recognized leadership styles, looking into the differences between several leadership types. In comparison with transformational leadership (TL), the SL style is increasingly centered around the psychological needs of followers as an objective in itself, while transformational puts these requirements discretionary to the organizational goals (

Van Dierendonck et al. 2014). In a broader context, literature primarily supports two leadership styles, i.e., servant and transformational, as both have received significant attention from scholars. However, there are subjective and comparative differences between these styles among scholars.

When we talk about transformational leaders’ thought processes, they prefer to concentrate on followers’ needs, to empower them in accomplishing authoritative objectives more readily. In contrast to this, servant leaders’ primarily want to serve first and focus on followers’ development.

Stone et al. (

2004) have suggested that hierarchical objectives are just a side-effect accomplished over a long haul of a purposeful spotlight on followers’ needs. Based on this discussion, SL followers have a more prominent probability to be served first in comparison with TL followers (

Sendjaya 2016). The servant-style considers giving free depictions of what, why, and how style carry on towards their supporters as they do. Greenleaf first coined the concept of SL in his essay titled “The servant-leader is servant first. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or to acquire material possession. The leader-first and the servant-first are two extreme types. Between them there are shadings and blends that are part of the infinite variety of human nature”.

Endeavors to characterize SL dependent on its results (for example, organizational citizenship behavior), models (for instance, benevolent behavior), or less significantly, predecessors (for example, character) have brought about clarifications possibly too tangled to be helpful for the two researchers and professionals. Remembering this, another significance of SL, elaborated as (i) SL is an approach to manage organization (ii) through one-on-one individual interactions to meet requirements and interests, and (iii) mitigating anxiety and stress of followers and enhance employee and organizational performance.

The aforementioned discussion has three features that explicitly make up the substance of SL, its intention, style, and attitude. In any case, the reasoning of SL (for instance, ‘other-organized approach to manage authority’) does not start from inside yet outside the pioneer, as the hidden ‘specialist first’ seems to suggest. Essentially, and it changes mind consistently, the motivation behind Greenleaf is that he gave his booklet the title: ‘the servant as leader,’ not ‘the leader as servant.’ Considering everything, an essential piece of servant leadership, and where it isolates itself from various organizational perspectives, is the secret individual motivation for taking up a power obligation. This course towards others reflects the pioneer’s motivation, conviction, or conviction that pushing others suggests an advancement away from self-heading.

2.3. Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy (SE) refers to a person’s confidence in their capacity to accomplish a constructive result from an undertaking or movement (

Bandura 2012). SE has three measurements parameters, e.g., (i) magnitude applies to the degree of assignment difficulty that an individual accepts the person in question can achieve. Secondly, (ii) strength alludes to whether the conviction concerning greatness is strong or weak. Generality demonstrates how much the desire is summed up across circumstances (

Bandura 1977).

Bandura et al. (

1977) have underlined that SE behavior must be estimated absolutely in examining adequacy and that measures should be custom fitted to the space being considered. It is critical to concentrate on explicit undertakings and to evaluate adequacy recognition and execution over a scope of expanding task trouble. Bandura’s measures represent a microanalytic research approach and survey the quality, extent, and all-inclusive statement of self-viability. Banduras has explained that individual SE interprets data from four sources: (i) mastery experience, (ii) vicarious experience, (iii) social persuasions, and (iv) physiological states. The most compelling of these four sources is mastery experience (

Bandura 1997). Mastery experience results from an individual participating in an undertaking and accomplishing what they see as a positive result. This experience of dominance prompts expanded understandings of their abilities incomparable performances (

Zelenak 2015).

People with such beliefs are certain about their ability to adapt to issues and effectively search for better approaches to perform complex assignments and difficulties. The study conducted by

Aguilar and Yuan (

2010) additionally affirmed that supervisors with low self-efficacy need belief and neglect to deal with business activities adequately. Moreover, it is believed that profoundly compelling individuals are relied upon to utilize everything and are ready to create assets in their workplace to manage difficult assignments. Essentially, researchers have concluded that individuals with high levels of self-efficacy are better at tackling issues as compared to an individual with low degrees of belief. Thus, in light of the abovementioned hypothetical confirmations, it very well may be presumed that self-efficacy is a fundamental individual belief that is conceivably useful in employee performance.

2.4. Benevolence Values

Individual values are originations of attractive end expresses that reflect what is imperative to us in our lives (

Feather 1990,

1995). For instance, an individual may consider herself as an individual who values equality and social equity. The traditional method to satisfy these qualities is by carrying on in manners that express them, by dedicating time to improve the lives of others. Although various empirical investigations bolster a value–behavior relation (

Schwartz 2013), the changeability in the size of this relationship across different worth spaces proposes that its quality might be affected by encouraging or impeding factors (

Bardi and Schwartz 2003). Schwartz has recognized ten unique kinds of values that are discernable by individuals in many societies (

Figure 2).

Loving one’s fellow people benevolence is a fundamental concept in a value belief system. The leader carrying benevolence values cares about people. Love your fellow people, the benevolent leader takes good care of their followers needs and helps them to achieve their goals. A great leader appreciates their followers and can choose the right person for right job (

Schwartz and Rubel-Lifschitz 2009) Benevolence preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is close is helpful, caring, loyal and supportive. These characteristics, e.g., being humble, uprightness, persistent, simplicity, and honesty, are very close to benevolence. On the other hand, decorated words such as flattery and smooth talk rarely reach the realm of benevolence.

To be humble is thus suitable. Humbleness is the basis of servant leadership. The leader is to serve their people. It is better to be benevolent, doing a little kindness near or at home, than go far away to burn anger (

DeYoung 2020;

Otto et al. 2021). Being centered; everyone can attempt to do good and do all kinds of kind actions and small acts with significant consequences. Additionally, these include helping a coworker succeed, cheering a coworker who is down or having problems, helping others be a better team player, and infecting others with happiness. The literature considers benevolence to be a good main characteristic (

Sun and Shang 2019). Research has firmly acknowledged that one should make it one’s core value to do one’s best for other people and be dependable in what one says. According to

Page et al. (

2021), leaders should incorporate benevolence, kindheartedness, and other-centeredness; and deal with their subordinates like relatives and give them consideration, direction, training, and support, since one should be respectful and cooperate with other individuals or groups calmly, incongruity and with a feeling of solidarity.

2.5. Servant Leadership with Employee Performance

Empirical investigations have confirmed the effect of servant leadership on employee performance. The previous studies have revealed the relationship between leadership style other key variables, e.g., job satisfaction (

Mayer et al. 2008), organizational commitment, turnover intention (

Hunter et al. 2013), and innovation (

Neubert et al. 2008). While research has already established a direct relationship between servant leadership and employee performance (

Liden et al. 2008), little is known about factors that can explain this relationship through mediating mechanisms (

Liden et al. 2014a). Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between servant leadership and task performance either at unit or individual level (

Neubert et al. 2008). Further, little research has inspected the relationship between servant leadership and three dimensions of individual employee performance as sub constructs, e.g., task performance, adaptive performance, and contextual performance. Recognizing these three dimensions are significant because the earlier research has revealed that performance can be measured through multiple dimensions (

Van Scotter et al. 2000).

Servant leadership depends on the reason that servant leaders build trust by benevolently concentrating on serving followers’ needs; they can construct reliable relationships that will, in general, draw out the best in the entirety of their supporters. Understanding the knowledge of followers’ needs can enhance their abilities (

Liden et al. 2008). Servant leaders putatively enable followers’ commitment in accomplishing group task performance objectives and strengthen the group’s critical thinking abilities that are essential for viable teamwork, and thus positively impact task performance (

Liden et al. 2008,

2014a). These ongoing collaborations between servant leaders and colleagues decrease representatives’ impression of contrasts in relationship quality with their pioneer. As servant leaders worth and fabricate trust in all colleagues, it limits the production of sub-gatherings. In this way, it actuates followers to strengthen ties, connect with and participate vigorously to achieve assignments, and subsequently upgrade the group union. Servant leadership appeared to help fulfill psychological needs, prompting commitment (

Van Dierendonck et al. 2014). Servant leadership categorically predicts influence-based trust in the followers and improves group-level performance. In conclusion, for example, the common faith in aggregate capacities intervenes in the connection between worker initiatives and group task performance.

Servant leaders share their shrewdness, create understanding, and grant it to followers (

Russell and Stone 2002). This shows that they attempt to convince their subordinates instead of constraining them to complete judgment or utilizing manipulative techniques (

Van Dierendonck 2011). For example, in their conversations with subordinates, servant leaders act with integrity and show consistency in actions and morality; and be true to themselves and the spirit of the leadership principles they preach (

Van Dierendonck et al. 2014). Servant leaders delegate authority to their subordinates and enhance their development (

Van Dierendonck 2011). They center around stewardship (for example, social obligation), giving guidance (for example, providing the correct level of responsibility), demonstrating relational acknowledgment (for example, compassion), and being genuine (for example, keeping guarantees). Humbleness, which centers around putting representatives’ inclinations first, is an essential component of servant leadership. As highlighted by

Van Dierendonck (

2011), working from a need to serve does not suggest a disposition of servility, as the force lies in possession of followers.

Hoch et al. (

2018) have further described that the relationship between authentic leadership and adaptative performance r = (0.12) was less than the relationship between servant leadership and adaptative performance (0.23).

Bass (

1985) has revealed that transformational leaders communicate the organizational vision persuasively and convince their followers to apply extra effort in work. Similarly, past studies have confirmed a favorable effect of transformational leadership on additional job practices (

Piccolo and Colquitt 2006). Very few studies have investigated the effects of TL on CP (

Judge and Piccolo 2004). This lack of research on CP can be attributed to the significant amount of research on task performance, which is considered an integral part of job responsibilities (

Podsakoff et al. 1996). In a similar manner, this gap of literature has been explained by

Borman and Motowidlo (

1993), that literature experts have given more attention to task performance than CP. Based on previous literature current study focuses on employee performance as endogenous variable, measuring it with three dimensions, e.g., task performance, adaptive performance, and contextual performance.

2.6. Servant Leadership with Benevolence Values

The literature on leadership shows the conflicting view between the two leadership styles, e.g., servant leadership (SL) and transformational leadership (TFL), that have differences and similarities.

Van Dierendonck et al. (

2014) concluded that both SL and TFL were associated with organizational commitment, performance, and job commitment. In spite of their differences and similarities, SL works essentially advocate follower need fulfillment, while TFL predominantly supports initiative viability.

Egri and Herman (

2000) have conducted a study based on the meeting. The survey acquired data from 73 leaders of for-profit organizations. The result has shown that these leaders’ very own qualities were more eccentric, open to change, and self-transcendent than directors in different organizations. These leaders or managers were routinely performing both types of leadership styles, e.g., transformational and transactional leadership. As hypothesized, nonprofit environmentalist organizations were highly receptive contexts for transformational leadership, whereas for-profit environmental organizations were at least moderately receptive in this regard.

Fu et al. (

2010) believed that personal values, especially self-transcendence worth direction, are a significant part of transformational leadership and help to explain transformational leadership constructs. Based on the literature, the study hypothesized these constructs. The study further explains that the two personal values, e.g., self-transcendence benevolence and universalism, positively impact transformational leadership (

Morrison 2018).

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Servant leadership has a positive relationship with benevolence values.

2.7. Benevolence Values with Employee Performance

As indicated by

Schwartz (

1994), values are mixed into individuals’ effects and feelings. They can deliver explicit attractive objectives of being among individuals. Accordingly, they rise above explicit activities and practices. Individuals may hold various qualities with changing levels of significance (

Schwartz 2012). Self-transcendence quality qualities are credited to benevolence and universalism. These two qualities start from the requirement for relationship and endurance (

Schwartz 2012). Benevolence and universalism cause general emotional practices of worry for other people, society, climate, and unselfishness.

Consequently,

Cannavale et al. (

2020) have investigated the impact of benevolence on performance, and explained leader personal values, such as “core values throughout everyday life”.

Schwartz (

2012) has investigated the influence of enterprise practices at the hierarchical level through essential dynamic perceptions (

Richard et al. 2009). The result has confirmed a positive relationship between CEO other-direction values and employee orientation towards performance. Based on the previous literature, this study hypothesized the relationship between benevolence value and employee performance.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Benevolence values have a positive impact on employee performance.

2.8. Servant Leadership with Self-Efficacy

According to

Schyns’ (

2001) research, a positive relationship between transformational leadership and occupational self-efficacy has been confirmed. Similarly,

Gong et al. (

2009) have explained the relationship between a supervisor’s leadership style, specifically TL, and employee self-efficacy. Study results demonstrate the significant and positive impact of TL on employee self-efficacy.

Felfe and Schyns (

2006) have focused on occupational self-efficacy and tend to recognize the importance of transformational supervisors’ leadership. Several researchers have studied self-efficacy with servant leadership in different sectors, showing self-efficacy’s positive effects on performance (

Haider and Mushtaq 2017;

Kwon and Kang 2017;

Song and Kwon 2017;

Walumbwa et al. 2010). According to the aforementioned findings, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Servant leadership has a positive impact on self-efficacy.

2.9. Self-Efficacy with Employee Performance

Self-efficacy is an individual’s faith in their capacity to create and make accomplishments by evaluating experience. This belief drives people to perform sufficiently and adapt to circumstances experienced in a usual manner (

Bandura and Walters 1977). Self-efficacy impacts on close to home conduct as the way toward suspecting, inspiration and feeling.

Bandura (

1986) expressed that self-efficacy drives an individual to pick behavior identified with their capacity to accomplish something. This individual likewise exhausts exertion and ingenuity to acquire or achieve the ideal objective. An individual with high self-efficacy is bound to perform specific practices with the exclusive standard.

On the other hand, an individual with low self-efficacy will probably perform at lower desire levels (

Yusuf 2011).

Carter et al. (

2018) and

De Clercq and Haq (

2018) have proposed that SE affects employee performance emphatically at individual and hierarchical levels. Workers with high self-efficacy are sure and propelled to work well, as anticipated by the supposition of the framework hypothesis that input impacts yield.

Stajkovic et al. (

2018) have founded that workers with high levels of self-efficacy is more averse to abandon the quest for their duties. Recently

Pratiwi and Nawangsari (

2021) have studied the relationship between self-efficacy and employee performance using partial least square (PLS) results confirms a positive relationship between self-efficacy and employee performance. Based on these findings, this study hypothesized the following relationship.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Self-efficacy has a positive relationship with employee performance.

2.10. Self-Efficacy with Benevolence Values

Personal values in relation to empathic self-efficacy convictions are positively related. The stronger the relationships between openness to change and self-efficacy and personal values, the more positive the impact on self-transcendence and teachers’ self-efficacy (

Barni et al. 2019;

Caprara and Steca 2007).

Caprara and Steca (

2007) have analyzed an estimated model in which self-efficacy and personal values such as self-transcendence include the benevolence values and universalism values and advance prosocial conduct. The research results have highlighted significant fluctuation in prosocial behavior, from 41% to 70% in the two genders. Results have confirmed the impact of personal values, especially transcendence, on self-efficacy. In their recent study,

Kim and Park (

2020) have identified that self-transcendence, which includes both values, mediated the relationship between self-efficacy and life satisfaction. While self-efficacy was significantly positively correlated with self-transcendence values. This study, based on the previous literature, hypothesizes the following relationship.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Self-efficacy has a positive relationship with benevolence values.

2.11. Self-Efficacy and Benevolence Value as a Mediating Variable

Personal values may improve work meaningfulness by giving direction associated with all life and work perspectives. People may discover their life reason through close to personal objectives (

Grant 2008). Others may feel called to satisfy a personal values reason that gets enduring and profound seriousness three different ways. In the first place, individual self-transcendence asks, “what would I be able to contribute?” Servant leadership increases job meaningfulness through enhancing newcomers’ values of self-transcendence (

Jiang et al. 2015). Research studies have reported the impact of self-transcendence on altruistic behavior as a mediating variable. The results from structural equation modeling supported the hypothesized model (

Dagar et al. 2020).

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Benevolence values mediate the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

Servant leadership explains the changes in frontline employees’ performance behaviors. Representatives’ self-personality and self-efficacy mediated the relationship between servant leadership and service performance behaviors (

Chen et al. 2015). This is a study with a broader explanation, indicating that individuals with consistent self-belief convictions are more equipped to take care of tasks and give more prominent exertion when confronted with challenges, prompting predominant performance (

Chen et al. 2007). The literature explains that employees with strong self-efficacy also have more sure effects at work, and regularly identified with citizenship practices coordinated at clients (

Peng et al. 2016). In addition, employees with more productive beliefs are prone to go beyond typical job requirements, take the initiative, and be spontaneous and innovative in serving customers, all of which are indicators of prosocial behavior at work. Based on the above literature, this study hypothesized the following relationships.

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Benevolence values mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and employee performance.

Hypothesis 9 (H9). Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between servant leadership and benevolence values.

Hypothesis 10 (H10). Self-efficacy and benevolence values serially mediate the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

3. Methodology

To achieve research objectives, a quantitative methodology was used. Following the positivist philosophy using the deductive approach was employed to answer the research questions. The study used a quantitative approach, and cross-sectional data were collected from the private banks, e.g., Summit Bank Limited, Al Baraka Bank, Allied Bank, Askari Bank, Bank Al Habib, Bank Alfalah, Bank of Punjab, Faysal Bank, Habib Bank Limited, Habib Metro Bank, JS Bank Limited, Meezan Bank, Muslim Commercial Bank, Samba Bank, Soneri Bank, and United Bank Limited using adopted questionnaires.

3.1. Target Population

Specifically, severe and fast information and correspondence innovation transformed the banking sector (

Ratten 2008). Past research in the non-western context has made considerable progress in the banking sector (

Kaushik and Rahman 2015). Primarily, the financial banking sector made a significant contribution to Pakistan’s economy (

Ul Hassan et al. 2012). The banking sector has been through transitional and extraordinary changes. It includes customer oriented innovative solutions (

Kumar Behera et al. 2015). The current study aims to investigate the key antecedents of employee performance in the banking sector. The target population for the present study consisted of all permanent employees working in the private banking sector of Pakistan. The population refers to a set of individual or research objects with similar characteristics (

Sekaran and Roger 2016). Employees included in this research are of a private commercial bank, which consists of the operational manager, business development officer, client relationship officer, customer care representative, loan officer, bank officer, customer service representative. At the time of data collection, the combined total headcount of private commercial banks working currently in Pakistan is approximately 105,666 based on the available official count.

3.2. Sample Size

According to

Ferdinand (

2006), a sample is a subset of the populace that has a true representation of the populace. Sample size plays a significant role in validating results.

Ferdinand (

2006) recommended that a suitable sample size for SEM examination is between 100–200. The current study sample, i.e.,

n = 400, is relatively sufficient to acquire a decent proportion of goodness-of-fit. The required sample size was assessed to be 383 at a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error using sampling formulas and calculator form target population frame of 105,666 employees. To avoid low response rate issues keeping the post-COVID-19 situation initially, 560 questionnaires were distributed randomly among employees of the banking sector.

3.3. Survey Instruments

The current research has measured employee performance (EP) construct based on three dimensions, e.g., task performance, adaptive performance, and contextual performance, using 23 items scale developed by

Pradhan and Jena (

2017). Servant leadership (SL) was measured by a seven-items short modified SL-7 scale by

Liden et al. (

2015). The benevolence values (BV) variable was measured with six items from PVQ-RR scale by

Schwartz (

2012) using a 5-point Likert scale. This scale shows the level of agreement and disagreement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Self-efficacy (SE) was measured with seven-item scale consistent with

Bandura (

2006) scale developed by

Borgogni et al. (

2010). The complete details of items are presented in

Appendix A.1.

3.5. Data Collection and Response Rate

The researcher first identifies the private banks in Pakistan and takes official permission for the survey’s purpose. Survey instruments were based on SL, EP, BV, and SE, respectively. The participants were given assurance that the responses would be kept confidential. The researcher collected data from the employees working in sixteen various private banks employee. The required sample size for this population should be 383 at a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error. To avoid low response rate issues keeping the post-COVID-19 situation initially, 560 questionnaires were distributed among employees of the banking sector. However, 400 questionnaires were returned, showing a 71% response rate. The survey was personally administered. Response rate above 50% acceptable and recommended for a personally administrated survey. To assess the detailed questionnaire’s items (See

Appendix A.1).

5. Research Findings and Discussion

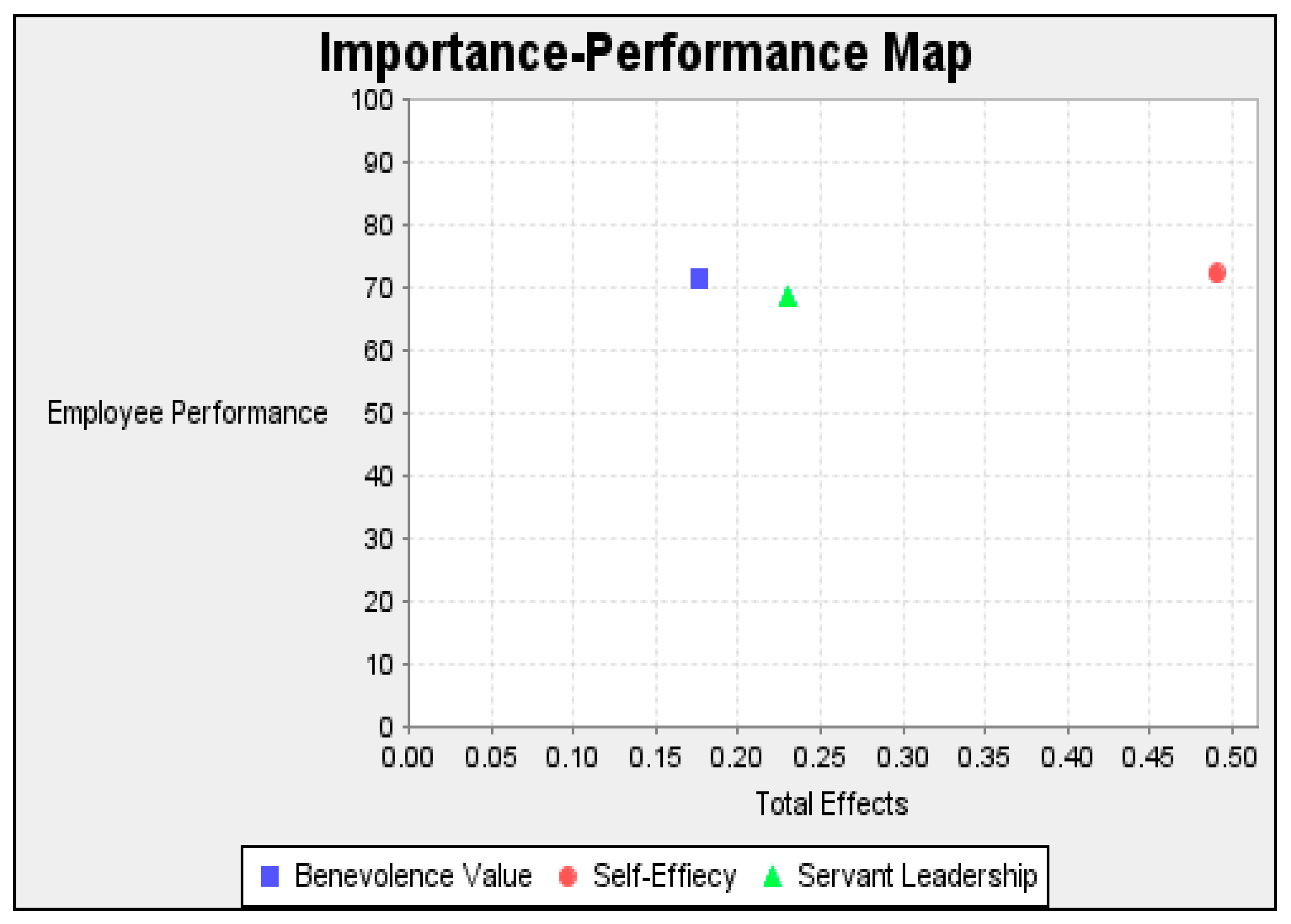

Current study investigates the mediating role SE and BV on the relationship between SL and EP. This research aims to investigate enhance our understanding about the impact of servant leadership on employee performance through mediating role of benevolence values and self-efficacy. To begin with, we have found significant supportive evidence for justifying our hypothesized relationships among SL and EP via indirect effects of BV and SE among employees of banking sector.

The structural equation model technique (SEM) was employed to check the mediating role of benevolence values and employee self-efficacy on the relationship between SL and EP. Our research study was based on three major objectives first, to test the indirect effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance. The results have confirmed that self-efficacy partially mediate the relationship between the servant leadership and employee. These results are aligned with the previous research findings that established a positive relationship between servant leadership and self-efficacy. Moreover, a significant relationship exists between employee self-efficacy and its impact on performance (

Almahdali et al. 2021;

Harwiki 2016;

Pratiwi and Nawangsari 2021;

Zeeshan et al. 2021). The second objective was to test the indirect effect of benevolence values on the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance. Benevolence values fully mediate the relationship between SL and EP.

Morrison (

2018) has concluded that values of leadership, especially benevolences, impact the leadership style. Building on this further confirmed that benevolence values mediate this relationship and positively impact the performance. Third objective was to test the serial mediation of self-efficacy and benevolence values on the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance. The result confirmed both SE and BV serially mediate the relationship between SL and EP. The variance accounted for (VAF) value shows 90% establishing full serial mediation. According to

Barbuto and Wheeler (

2006), servant leaders can improve employee performance, such as the additional work made by employees, and increase organizational effectiveness. Leaders should perceive the positive consequences of their leadership in engaging and fostering their individuals to give work fulfillment, eventually adding to the employee involvement and working on their performance.

Servant leadership has no immediate impact on task performance, adaptive performance as at first model consisted of these factors, although it directly affects the contextual performance. These findings are significant since they affirm the principal reason of servant leadership on values of employees and leaders, especially the relevant mediation role of benevolence values. Our research responds to the previous call, that was given to investigate the mediating effect of these values on the relationship between servant leadership and’ performance (

Chiniara and Bentein 2018). Our work additionally expands the understanding of the impact of SL on EP using SE and BV as mediators at the individual level. It explains the indirect effects of how benevolence values and self-efficacy intervenes between these relationships. Our findings are aligned with the previous research results that self-efficacy positively impacting leadership and performance. Likewise,

Ji and Yoon (

2021) have also highlighted self-efficacy as an integral component in explaining servant leadership.

There is an aberrant effect of servant leadership on employee performance.

Chiniara and Bentein (

2016) have concluded that “servant leaders tend to build trustworthy dyadic relationships with followers and create a psychologically safe and fair climate where employees strongly feel they can be themselves, make their own decisions, and feel connected to others, which naturally leads to the adoption of helpful behaviors towards colleagues and conscientious behaviors in favor of the organization” (p. 136). Mediation test results also establish how both benevolence values and self-efficacy build and both mediate and positively impact the relationship of servant leadership and employee performance. In keeping with the conceptual attributes of servant leadership, these results suggest that benevolence values and self-efficacy, established through mutual exchange of concern and care between the subordinate and leader, are translated into positive work outcomes.

6. Research Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

This research brings important theoretical and practical implications for employees’ financial industry experts and behavioral researchers. Employees have open conversations regarding serving and being a worker. Servant leaders do not need to be officially designated. Employees at any position and in any situation can go for servant leader behavior. Research findings conclude that values and beliefs both act as significant predecessors of performance. At a practical level, it would be beneficial for leaders to train colleagues on the most proficient method to take part in leadership practices to increase performance. The managerial implication of this study brings relevant implications for the HR administration and the overall management that these findings can be utilized to acquire a comprehensive insight into employee performance. Employee performance is exceptionally dependent upon leadership style. Worker performance is highly subject to the upsides of leaders alongside the employee belief. The findings of this research can significantly contribute to the banking sector and enable them to improve their employee’s performance. Leaders and managers should not only provide work orders and should facilitate workers who genuinely need help to focus on their tasks. Likewise, in connection to this, employees should also attempt to practice their leaders’ values and reciprocally offer help and support to each other to improve their work performance genuinely.

This study also brings some limitations. This research has employed primary data that is cross-sectional in nature. The employees of private banks participated in this research. However, the result of this study is only applicable to the banking industry. Current research findings cannot be generalized to other sectors. This study uses relatively a small sample, e.g., (400), for analysis; keeping this in mind, future studies should employ longitudinal and multi-wave data using bigger sample to enhance generalizability of results (

Sekaran and Roger 2016).

We also strongly recommend that future studies should consider other antecedents in the model that predict employee performance by using demographic variables as moderators. Literature provides evidence for team performance (

Tekleab et al. 2016). To extend the debate on performance, we suggest researchers should assess team performance in the future. Lastly, servant leadership theory talks about the influence of leaders on their surroundings (

Greenleaf 1991). Our findings revealed how we could make serving society. We assumed that this phenomenon happens through a leader’s model, yet we could not empirically test it. Future research might adopt an organizational approach to assess the genuine impact of servant leaders on their employees in a different corporate setting.