When the Going Gets Tough, Leaders Use Metaphors and Storytelling: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Communication in the Context of COVID-19 and Ukraine Crises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Metaphors

2.1.1. Definition and Importance of Metaphors

2.1.2. Types of Metaphors

- Structural metaphors provide mappings between the source and target domains. For example, the metaphor “Salvation is a journey” maps extant knowledge on the concept of journey onto the concept of salvation and vice versa.

- Orientational metaphors help make sense of concepts “in a coherent manner, based on our image-schema knowledge of the world”. They can be powered by words that signify orientation (e.g., up, down, front, and back), or position (e.g., on or off)—for example, “Sadness is down”, “Happiness is Up”, etc.

- Ontological metaphors are the ones involving ways of viewing intangible concepts (feelings, activities, and ideas) as entities that can in turn be categorized, grouped, and quantified in order to fathom them more completely. In essence, they can help people share their experiences in a concrete way, as well as identify, refer to, and quantify their non-physical aspects, as exemplified by the phrase “my battery died”.

- Absolute metaphors were conceptualized by the German philosopher and intellectual historian Hans Blumenberg in 1960, in his work “Paradigmen zu einer Metaphorologie” (Blumenberg 1960). According to his work, absolute metaphors’ utility is in enhancing speech under the influence of rhetoric. In this type of metaphor, selected concepts are transferred to a non-literal, almost metaphysical plane. Then, through the repeated use of the constructed metaphor, a permanent connection is formed between the components of the metaphor; it becomes a norm and is effectively embedded in the culture. For example, in the expression “the naked truth”, as truth itself has no physical existence, it cannot literally be ‘naked.’ Similarly, the word “box” can be used to describe a house, and “tube” to describe a train. However, the distinctness and meaning of this metaphor have made it prevail in multiple cultures and languages (German, English, Greek, etc.).

- Extended Metaphors: The extended conceptual metaphor theory has more recently been brought forth by Zoltan Kövecses (Kövecses 2021), which builds on Lakoff and Johnson’s metaphor theory by adding “extended metaphors”. According to this theory, and as indicated by their name, extended metaphors are lengthened versions of an already established metaphor. Moreover, to further define and describe this type of metaphor, one has to take into account that – apart from their cognitive characteristics that fall into the description of standards theory on metaphor – they also bear a strong contextual component. Thus they seem to simultaneously exist on four hierarchical levels of schematicity (image schemas, domains, frames, and mental spaces). An example of an extended metaphor is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech, where the rights and freedoms that many Black Americans were fighting for are described in the context of a detailed, accounted-for ‘dream’ of a future reality (Kövecses 2021).

- Dead (cliché) metaphors: For a metaphor to be dead (cliché), it has to have lost its metaphorical qualities (Gibbs 2011) and have crossed the boundary to normal, literal speech towards becoming an ordinary part of the literal vocabulary used in everyday discourse (Grey 2000). This can be exemplified by the fact that a person can fully understand the expression “falling head-over-heels in love” even if they have never encountered that variant of the phrase “falling in love” before. The boundaries between metaphorical and literal speech may thus have been crossed to the point where some argue that the dead metaphor should not be considered a metaphor at all but rather classified as a separate vocabulary item. The category of “dead metaphor” was added by George Lakoff in 1987 and defined as “a linguistic expression that had once been novel and poetic but had since become part of the mundane conventional language” (Lakoff 1987). It emerged from the fact that traditional folk theories of language seemed to treat metaphors in a way that, over time, has been proven not to be workable. In this case, the locus of a metaphor was basicallyon the language used (increased eloquence), instead of thought. As ordinary everyday language tended to be more ‘literal’ in its nature, mundane, unpoetic language was believed to not be able to support metaphorical expression, and thus novel poetic or rhetorical expressions were in turn candidates for being metaphors. As, over time, such ‘novel’ (then) metaphorical expressions have (now) become embedded in everyday language use, they have lost their ‘novelty’ altogether. Moreover, while the source for some dead metaphors is widely known or their symbolism easily understood (e.g., “falling in love”), in other cases most people may not be aware of their origins at all (e.g., “to kick the bucket”).

- Visual Metaphors: Although a number of studies have explored visual metaphors in very diverse genres, such as advertising, films, cartoons, and visual displays for training and control purposes, there is little agreement among researchers over their definition (Refaie 2003). In essence, they entail the utilization of visual elements to create a metaphor through the comparison of the properties of contextually diverse objects within the same context. Modern advertising relies heavily on the utilization of visual metaphors, such as placing a picture of a car next to a tiger, in order to suggest that the car has similar qualities of speed and power (van Mulken et al. 2014). Moreover, the visual metaphor is also considered a common and expected device in political cartoons (van Mulken et al. 2014), for example, when the face of a particular politician is visually amalgamated with the body of a specific animal (Refaie 2003). Finally, moderately challenging visual metaphors are usually more appreciated by their audience than simpler or more complex metaphors (van Mulken et al. 2014).

- Mixed Metaphors: To be considered mixed metaphors, metaphors need to satisfy two basic conditions. They should occur in textual adjacency (i.e., within a single metaphor cluster) and should not (for the most part) share any imagistic ontology or any direct inferential entailments between them (Kimmel 2010). In essence, in some cases, a metaphor may belong to multiple conceptualized categories at once (Kövecses 2016). These kinds of metaphors fall into the category of “mixed metaphors”. Several metaphor scholars argue that mixed metaphor is a phenomenon that conceptual metaphor theory cannot handle, due to the premise that once a conceptual metaphor is activated it should normally lead to and support the use of further linguistic examples of the same conceptual metaphor. However, according to Kovecses, in real discourse, most metaphors are mixed in nature due to the fact that conceptual metaphors are not activated in practice and do not often lead to further consistent linguistic metaphors of the same conceptual metaphor. Finally, the power of a mixed metaphor lies in its ability to delight and surprise readers and to challenge them to move beyond notions of “correct” or “incorrect” metaphors, as illustrated through William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who considers the question “to take arms against a sea of troubles”, where a strictly literal completion of the metaphor would demand the use of a word such as ‘host’ instead of the word ‘sea’ (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2023).

- War metaphors are abundant in extant literature on leadership, as illustrated by the existence of “A ‘field book’ analysis of Jack Welch’s leadership style, advertising itself as a ‘battle plan’ for a ‘revolution’, or “The Wounded Leader”.

- Game and Sports Metaphors: Another group of leadership metaphors is drawn from the world of playing games and sports, such as golf (leaders “trust their swing”), or even the “great game of life”. These metaphors often emphasize the constructed and changeable nature of the context within which leadership takes place, encouraging the leader to either “toy around” with different game rules (in game metaphors) or practice to achieve leadership mastery (in sports metaphors).

- Art Metaphors: Leadership has been often presented as art—e.g., the art of acting and performing, the similarity of leadership to being the conductor of an orchestra, producing “an expressive and unified combination of tones” or acknowledging the need to “turn his back on the crowd”.

- Machine Metaphors: Frequently, leadership is linked to machine metaphors, which build on concepts drawn from engineering and industrial production, with leaders being portrayed as—or even operating—machinery (e.g., “the leadership engine”).

- Religious/Spiritual Metaphors link the concept of leadership to spirituality, often calling upon concepts such as the “temptations”, or “obsessions” of successful leaders, and linking them to “fables”. In other cases, leadership is linked to magic or fairy tales, as evident in the suggestion that a leader “can never close the gap between himself and the group”, which represents a physical-spatial metaphor, implying that a leader may possess extraordinary or super-human powers.

2.1.3. Metaphors in Leadership and Politics

2.2. Storytelling

2.2.1. Definition and Importance of Storytelling

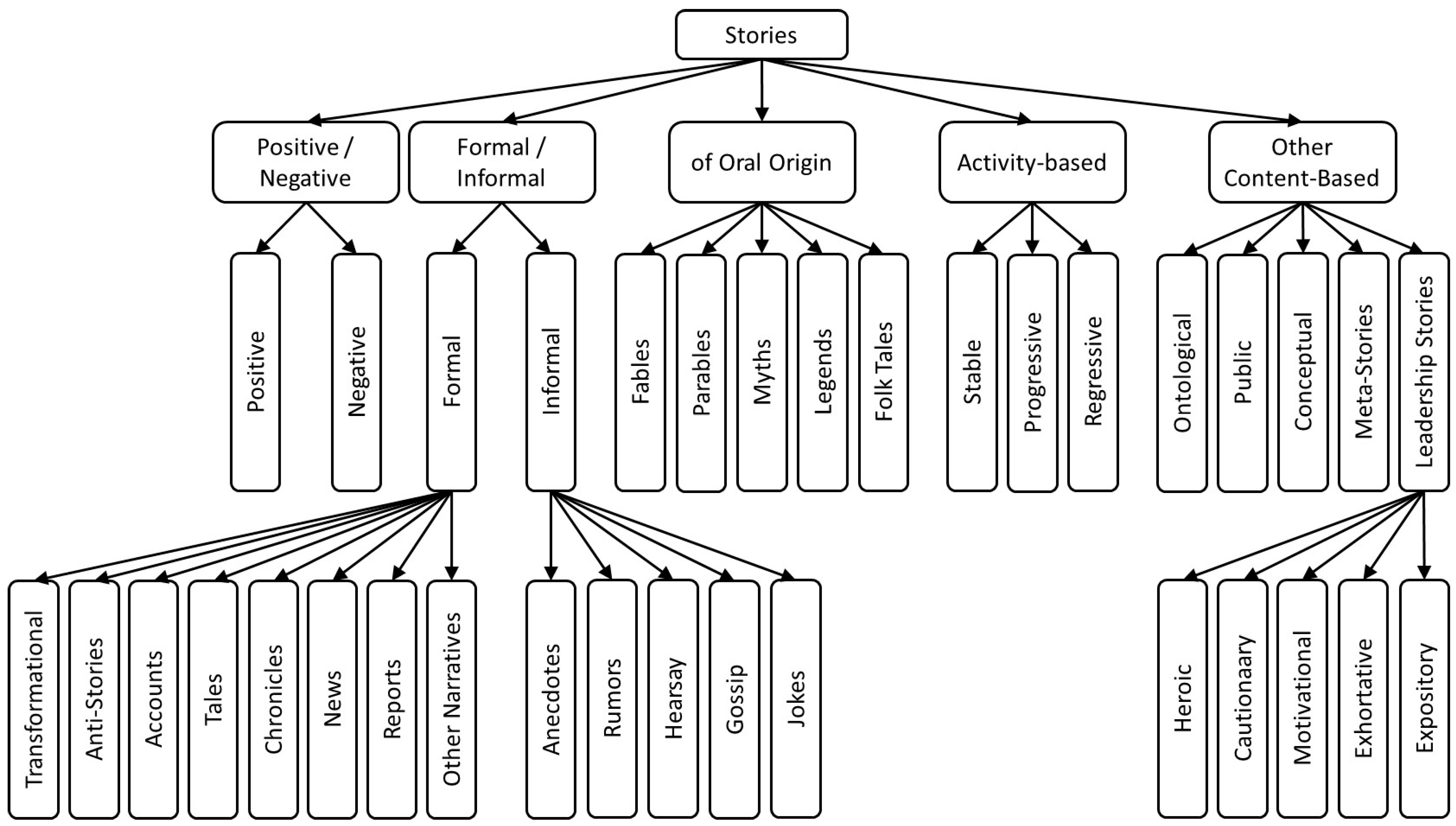

2.2.2. Types of Stories in Storytelling

- Positive and Negative stories. Both types are present in any organization (Denning 2004; Mládková 2013):

- Positive stories are about victories, fulfilled desires, and wishes. They help in the creation and sharing of vision and objectives, to create new organizations, states, families, teams, and communities, and to create an understanding of the standpoints of others.

- Negative stories are about danger, problems (solved or unsolved), and defeat. They help us to acquire new knowledge, as well as understand and change the terms of present reality, and ultimately enable us to learn through the description of mistakes, moments of ignorance, and difficulties people had to overcome in the past.

- Formal and Informal stories (Mládková 2013):

- Formal stories are used in formal communication and feature a number of different sub-types:

- Transformational stories: Also known as springboard stories, they are powerful enough to enable the sharing of very complex tacit knowledge and change people’s perceptions of reality. They also have high potential in management (Denning 2004).

- Anti-stories: Stories created in response to another story with the aim of negating it. Their usage is risky, as they may have a negative impact on their creators if they are inaccurate or based on lies.

- Accounts: Brief descriptions of a situation.

- Tales: They may contain both true and fictive events.

- Chronicles: Historical accounts of facts and events in the order in which they occurred.

- News: They carry new information (e.g., news in the media).

- Reports: They periodically provide information on the actual state in connection with specific activities or phenomena.

- Other Narratives: Whatever is said in the form of a story (not in any of the previous categories)

- Informal Stories:

- Anecdotes: Short, entertaining stories, usually with regard to the adventures of one or more individuals.

- Rumors: Stories that are not based on knowledge or proven by facts.

- Hearsay: A story that the storyteller has become the recipient of but has not yet confirmed its validity.

- Gossip: Sharing personal, unverified information with regard to other people.

- Jokes: Humorous anecdotal stories usually aimed at entertaining but also able to effectively serve as transformational stories under the right circumstances.

- Stories of Oral Origin/Fables, parables, myths legends, and folk tales stories originally told verbally, later transferred to a written form) (Mládková 2013):

- Fables: Fictive stories where the protagonists are usually animals who represent people and usually contain a moral lesson.

- Parables: Brief accounts of well-known events that carry moral or religious meaning.

- Myths: Popular stories from unknown authors, explaining nature, human nature, institutions, and religious habits, describing heroic acts of good performed by famous heroes, and inspiring the reader to improve their mental and physical abilities.

- Legends: Stories passed from generation to generation, outlining a historical background that cannot be proven.

- Folk tales: Mythical stories characteristic of a nation or a large population therein that differ from culture to culture and have become embedded in the cultural heritage of other nations. They usually discuss relationships between cause and effect, good and evil, and are given huge attention in tough times and during national uprisings.

- Activity-Based/Stable, Progressive, and Regressive stories, based on the activity of the protagonist (Gergen and Gergen 1986; Mládková 2013):

- Stable Stories: The protagonist tries to journey through the story and remain unchanged. When he succeeds, he is the same as he was at the beginning of the story.

- Progressive Stories: The protagonist develops to improve himself or his situation.

- Regressive Stories: The protagonist develops for the worse, or his situation worsens.

- Other/Content-Based:

- Ontological stories help co-create the identity and social position of an individual (e.g., the clichéd story about the role of sexes in a family, where the mother cooks and the father repairs things) (Mládková 2013; Somers 1994).

- Public stories are related to institutional and cultural forms and are related to human life and activity (Mládková 2013; Somers 1994).

- Conceptual stories are analytical models that explain something, like scientific theories (Mládková 2013; Somers 1994).

- Meta stories are widely known myths, ideologies, and cosmologies from which other types of stories are derived. They influence the culture and behavior of all types of human groups and organizations (Mládková 2013; Somers 1994).

- Leadership stories (Harris and Barnes 2006): In the context of leadership, the stories used by leaders to inspire and motivate may, in many cases, also be:

- heroic (you probably couldn’t do this)

- cautionary (never do this)

- motivational (you should try to do this)

- exhortative (always do this)

- expository (I did this, and this is what I learned)

2.2.3. Storytelling in Leadership and Politics

2.3. The Use of Metaphors and Storytelling by Leaders and Politicians in Practice

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Aim

3.2. Research Methodology

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Methodology

3.4. Characteristics of The Two Cases

3.4.1. The Greek “Success Story” during the COVID-19 Health Crisis

3.4.2. Ukraine’s Communication Success during the Ongoing (2022–2023) Conflict with Russia

4. Results

4.1. Usage of Metaphors and Storytelling by the PM of Greece during the COVID-19 Health Crisis

4.1.1. Identification of Metaphors and Storytelling Instances in the Greek PM’s Speeches

4.1.2. Types of Metaphors and Stories in the Greek PM’s Speeches

4.1.3. Intensity of Usage of Metaphors and Storytelling by the Greek PM during the Crisis

4.2. Usage of Metaphors and Storytelling by the President of Ukraine during the Ongoing Conflict

4.2.1. Identification of Metaphors and Storytelling Instances in the Ukraine President’s Addresses

4.2.2. Types of Metaphors and Stories in the Ukrainian President’s Addresses

4.2.3. Intensity of Usage of Metaphors and Storytelling by the Ukrainian President during the Crisis

4.3. Cumulative and Comparative Findings from Both Cases

5. Discussion & Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical & Practical Contribution

5.2. Study Limitations & Suggestions for Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaltio-Marjosola, Iiris. 1994. From a “grand story” to multiple narratives? Studying an organizational change project. Journal of Organizational Change Management 7: 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Paul. 2022. “Shame on you”: How President Zelensky Uses Speeches to Get What He Needs. BBC News. March 24. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60855280 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Akin, Gib, and Emily Schultheiss. 1990. Jazz Bands and Missionaries: OD through Stories and Metaphor. Journal of Managerial Psychology 5: 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amernic, Joel, Russell Craig, and Dennis Tourish. 2007. The transformational leader as pedagogue, physician, architect, commander, and saint: Five root metaphors in Jack Welch’s letters to stockholders of General Electric. Human Relations 60: 1839–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Carina, and Per Runeson. 2007. A spiral process model for case studies on software quality monitoring—Method and metrics. Software Process: Improvement and Practice 12: 125–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Dee H., Thomas D. Hull, and Jennifer A. Donahue. 2009. Storytelling as an Instructional Method: Definitions and Research Questions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning 3: 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. 2023. Metaphor. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/metaphor (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Archer, Allison M. N., and Cindy D. Kam. 2022. She is the chair(man): Gender, language, and leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 33: 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Chris, Robert Putnam, and Diana McLain Smith. 1985. Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, Joshua. 2023. Ukraine War: A Month-By-Month Timeline of the Conflict 2022–2023. Euronews. January 30. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2023/01/30/ukraine-war-a-month-by-month-timeline-of-the-conflict-in-2022 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Auvinen, Tommi, Iiris Aaltio, and Kirsimarja Blomqvistt. 2013a. Constructing leadership by storytelling—The meaning of trust and narratives. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 34: 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvinen, Tommi P., Anna-Maija Lämsä, Teppo Sintonen, and Tuomo Takala. 2013b. Leadership Manipulation and Ethics in Storytelling. Journal of Business Ethics 116: 415–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, John. 2003. Great Communication Secrets of Great Leaders. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Benjamin R. 2004. Audiences, metaphors, and the Persian Gulf war. Communication Studies 55: 447–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbasat, Izak, David K. Goldstein, and Melissa Mead. 1987. The case research strategy in studies of information systems. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems 11: 369–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björninen, Samuli, Mari Hatavara, and Maria Mäkelä. 2020. Narrative as social action: A narratological approach to story, discourse and positioning in political storytelling. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 23: 437–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenberg, Hans. 1960. Paradigmen Zu Einer Metaphorologie. Archiv Für Begriffsgeschichte 6: 7–142. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24355810 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Boal, Kimberly B., and Patrick L. Schultz. 2007. Storytelling, time, and evolution: The role of strategic leadership in complex adaptive systems. The Leadership Quarterly 18: 411–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boje, David M. 2001. Narrative Methods for Organizational and Communications Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bougher, Lori D. 2012. The Case for Metaphor in Political Reasoning and Cognition. Political Psychology 33: 145–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubich, Alen. 2022. Here’s What Leaders Can Learn from Zelensky’s Communication Style. Fortune. April 19. Available online: https://fortune.com/2022/04/19/leadership-zelensky-communication-style-media-war-social-leader-strategy-international-ukraine-invasion-alen-bubich/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Burke, W. Warner. 1992. Metaphors to Consult by. Group & Organization Management 17: 255–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammaerts, Bart. 2012. The strategic use of metaphors by political and media elites:The 2007–11 Belgian constitutional crisis. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 8: 229–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charteris-Black, Jonathan. 2006a. Britain as a container: Immigration metaphors in the 2005 election campaign. Discourse & Society 17: 563–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charteris-Black, Jonathan. 2006b. Politicians and Rhetoric. The Persuasive Power of Metaphor. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, Paul Anthony. 2003. Analysing Political Discourse: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ciulla, Joanne B. 1995. Leadership Ethics: Mapping the Territory. Business Ethics Quarterly 5: 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, Joanne B. 2005. The state of leadership ethics and the work that lies before us. Business Ethics: A European Review 14: 323–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleverly-Thompson, Shannon. 2018. Teaching Storytelling as a Leadership Practice. Journal of Leadership Education 17: 132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, Jay A. 1991. Inspiring others: The language of leadership. Academy of Management Perspectives 5: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, Jay A., and Rabindra N. Kanungo. 1987. Toward a Behavioral Theory of Charismatic Leadership in Organizational Settings. Academy of Management Review 12: 637–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, David. 2020. Pandemic and its metaphors: Sontag revisited in the COVID-19 era. European Journal of Cultural Studies 23: 1025–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Fernández, Eliecer. 2013. Words as weapons for mass persuasion: Dysphemism in Churchill’s wartime speeches. Text & Talk 33: 311–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, Michael F., and Dietram A. Scheufele. 2018. (Escaping) the paradox of scientific storytelling. PLoS Biology 16: e2006720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Landtsheer, Christ. 2009. Collecting Political Meaning from the Count of Metaphor. In Metaphor and Discourse. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, Stephen. 2001. The Springboard: How Storytelling Ignites Action in Knowledge-Era Organizations. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2004. Telling Tales. Harvard Business Review 82: 122–29. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2005. The Leader’s Guide to sTORYTELLING: Mastering the Art and Discipline of Business Narrative. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2006. Effective storytelling: Strategic business narrative techniques. Strategy & Leadership 34: 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, Stephen. 2011. The Leaders Guide to Storytelling, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, Larry M. 2002. Case Study Research and Theory Building. Advances in Developing Human Resources 4: 335–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, Anne Haas, and Celia Genishi. 1994. The Need for Story: Cultural Diversity in Classroom and Community. Illinois: The National Council of Teachers of English. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review 14: 532–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Melissa E. Graebner. 2007. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Academy of Management Journal 50: 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellet, William. 2007. The Case Study Handbook: How to Read, Discuss, and Write Persuasively about Cases. Brighton: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, A. E. 2009. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: Echoes of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer. Carbondale: South Illinois University (SIU) Press. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2023. Metaphor. Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/art/metaphor#ref159366 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Engel, Alison, Kathryn Lucido, and Kyla Cook. 2018. Rethinking Narrative: Leveraging storytelling for science learning. Childhood Education 94: 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlanger, Steven. 2020. Macron Declares France ‘at War’ with Virus, as E.U. Proposes 30-Day Travel Ban. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/16/world/europe/coronavirus-france-macron-travel-ban.html?searchResultPosition=3 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Fallon, Katy. 2020. How Greece Managed to Flatten the Curve. Independent (UK Edition). April 8. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/coronavirus-greece-cases-deaths-flatten-curve-update-a9455436.html (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Fryer, Bronwyn. 2003. Storytelling that moves people. Harvard Business Review. June. Available online: https://hbr.org/2003/06/storytelling-that-moves-people (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Gallo, Carmine. 2022. Zelensky’s Audience-Centered Speeches Connect To Shared Values. Forbes. March 17. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/carminegallo/2022/03/17/zelenskys-audience-centered-speeches-connect-to-shared-values/?sh=e6f96ed68846 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Gergen, Kenneth J., and Mary M. Gergen. 1986. Narrative form and the construction of psychological science. In Narrative Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Conduct. Edited by Theodore R. Sarbin. Westport: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, Mary M., and Kenneth J. Gergen. 2006. Narratives in action. Narrative Inquiry 16: 112–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 1994. The Poetics of Mind: Figurative Thought, Language, and Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 2011. Evaluating Conceptual Metaphor Theory. Discourse Processes 48: 529–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond W., Jr. 2015. Counting Metaphors: What Does this Reveal about Language and Thought? Cognitive Semantics 1: 155–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Rob. 2011. Using Storytelling to Maintain Employee Loyalty during Change. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Nicole A., and Leon Mann. 2004. Transformational leadership and shared values: The building blocks of trust. Journal of Managerial Psychology 19: 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Trends. 2023. Storytelling—Explore—Google Trends. Available online: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=today5-y&q=storytelling&hl=en (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Gov.UK. 2020. Prime Minister’s Statement on Coronavirus (COVID-19). March 17. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-17-march-2020 (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Graesser, A. C., J. Mio, and K. K. Millis. 1989. Metaphors in persuasive communication. In Comprehension of Literary Discourse: Results and Problems of Interdisciplinary Approaches. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, William. 2000. Metaphor and Meaning. Minerva, November 4. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs, Francis E. 2013. Citizenship, Character, and Leadership: Guidance from the Words of Theodore Roosevelt. Leadership and Management in Engineering 13: 230–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Alan G. 2004. Lincoln’s Use of Constitutive Metaphors. Rhetoric & Public Affairs 7: 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Craig. 2009. Book Review: Jonathan Charteris-Black, Politicians and Rhetoric. Lexis [Online], Book Reviews, Online since 26 March 2009, connection on 05 February 2023. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/lexis/1691 (accessed on 20 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Cynthia, Ian Palmer, and Nelson Phillips. 2000. Discourse as a Strategic Resource. Human Relations 53: 1227–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Jack, and B. Kim Barnes. 2006. Leadership storytelling. Industrial and Commercial Training 38: 350–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIT. 2020. Online Survey Conducted by the Institute of Communication and Literacy in Health and the Media (hit.org.gr) in Collaboration with the Healthpharma.Gr Portal’, 23–28 April 2020. Available online: https://www.in.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/eyuer1588602317474.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Inns, Dawn. 2002. Metaphor in the Literature of Organizational Analysis: A Preliminary Taxonomy and a Glimpse at a Humanities-Based Perspective. Organization 9: 305–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, Cindy D. 2019. Infectious Disease, Disgust, and Imagining the Other. The Journal of Politics 81: 1371–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Jin-Ae, Sookyeong Hong, and Glenn T. Hubbard. 2020. The role of storytelling in advertising: Consumer emotion, narrative engagement level, and word-of-mouth intention. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 19: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaszewski, Robert, and Rafał Drewniak. 2021. The Leading Traits of the Modern Corporate Leader: Comparing Survey Results from 2008 and 2018. Energies 14: 7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Albert N. 1996. On interpreting statements as metaphor or irony: Contextual heuristics and cognitive consequences. In Metaphor: Implications and Applications. London: Psychology Press, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Keizer, Jimme A., and G. J. J. Post. 1996. The metaphoric gap as a catalyst of change. In Organisation Development, Metaphorical Explorations. London: Pitman, pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- KelloggInsight. 2022. What Makes Zelensky Such a Strong Leader? KelloggInsight. March 23. Available online: https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/newsletters/what-makes-zelensky-such-a-strong-leader (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Kimmel, Michael. 2010. Why we mix metaphors (and mix them well): Discourse coherence, conceptual metaphor, and beyond. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, James M., and Barry Z. Posner. 2012. The Leadership Challenge. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2002. Cognitive-linguistic comments on metaphor identification. Language and Literature 11: 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2010. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2016. Chapter 1. A view of “mixed metaphor” within a conceptual metaphor theory framework. In Mixing Metaphor. Edited by Raymond W. Gibbs, Jr. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2021. Standard and extended conceptual metaphor theory. In The Routledge Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. London: Routledge, pp. 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, Gitte, Michel Achard, René Dirven, and Francisco J. R. de Mendoza Ibáñez. 2008. Cognitive Linguistics: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. Cognitive Linguistics: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William, and Joshua Waletzky. 1967. Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts. Edited by June Helm. Washington: University of Washington Press, pp. 12–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ladi, Stella, Angelos Angelou, and Dimitra Panagiotatou. 2021. Regaining Trust: Evidence-Informed Policymaking during the First Phase of the COVID-19 Crisis in Greece. South European Society and Politics, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George. 1987. The Death of Dead Metaphor. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 2: 143–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, R. T. 1990. Talking Power: The Politics of Language in Our Lives. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1993a. How metaphor structures dreams: The theory of conceptual metaphor applied to dream analysis. Dreaming 3: 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George. 1993b. The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor. In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cognitive Science 4: 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 2008. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lucarevschi, Claudio Rezende. 2016. The role of story telling in language learneing: A literature review. Working Papers of the Linguistics Circle of the University of Victoria 26: 24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lumby, Jacky, and Fenwick W. English. 2010. Leadership as Lunacy: And Other Metaphors for Educational Leadership. London: Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magra, Iliana. 2020a. Greece Has ‘Defied the Odds’ in the Pandemic. The New York Times. April 28. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/28/world/europe/coronavirus-greece-europe.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Magra, Iliana. 2020b. Coronavirus: Greece’s Handling of Outbreak Is a Surprising Success Story, So Far. Independent (UK Edition). April 29. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/coronavirus-greece-response-success-test-economy-reopen-a9489391.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Mayer-Schoenberger, Viktor, and Thomas Oberlechner. 2002. Through Their Own Words: Towards a New Understanding of Leadership through Metaphors (October 2002). KSG Working Papers Series RWP02-043. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, Becky, Laura Shallcross, Michael Wilson, Christopher Fuller, and Andrew Hayward. 2019. Storytelling as a research tool and intervention around public health perceptions and behaviour: A protocol for a systematic narrative review. BMJ Open 9: e030597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, Bryan. 2007. Distancing and showing solidarity via metaphor and metonymy in political discourse: A critical study of American statements on Iraq during the years 2004–2005. Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines 2: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mio, Jeffery Scott. 1996. Metaphor, politics, and persuasion. In Metaphor: Implications and Applications. London: Psychology Press, pp. 127–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mio, Jeffery Scott. 2009. Metaphor and Politics. Metaphor and Symbol 12: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, Jeffery Scott, Ronald E. Riggio, Shana Levin, and Renford Reese. 2005. Presidential leadership and charisma: The effects of metaphor. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mládková, Ludmila. 2013. Leadership and Storytelling. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 75: 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, Karin S. 2000. Metaphor Analysis in Psychology—Method, Theory, and Fields of Application. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum:Qualitative Social Research FQS 1: 21. Available online: http://qualitative-research.net/fqs/fqs-e/2-00inhalt-e.htm (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- OECD. 2020. Greece’s Response to COVID-19 Has Been Swift and Effective but Tackling Long-Standing Challenges Also Key. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/economy/greeces-response-to-COVID-19-has-been-swift-and-effective-but-tackling-long-standing-challenges-also-key.htm (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Ortony, Andrew. 1975. Why Metaphors Are Necessary and Not Just Nice. Educational Theory 25: 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, Michael M., and Douglas Ehninger. 1962. The metaphor in public address. Speech Monographs 29: 223–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottati, Victor C., and Randall A. Renstrom. 2010. Metaphor and Persuasive Communication: A Multifunctional Approach. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4: 783–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, Ken W., and Hans Hansen. 2007. The Organizational Story as Leadership. Leadership 3: 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacham, Henry. 1971. The Garden of Eloquence: Conteyning the Figures of Grammar and Rhetorick Set Foorth in Englishe. London: H. Iackson. [Google Scholar]

- Perrigo, Billy, and Joseph Hincks. 2020. Greece Has an Elderly Population and a Fragile Economy. How Has It Escaped the Worst of the Coronavirus So Far? TIME. April 23. Available online: https://time.com/5824836/greece-coronavirus/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Perry, Dewayne E., Susan Elliott Sim, and Steve M. Easterbrook. 2004. Case studies for software engineers. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Software Engineering. Edinburgh: ACM, pp. 736–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Tom. 1991. Get Innovative or Get Dead. California Management Review 33: 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilyarchuk, Kateryna, and Alexander Onysko. 2018. Conceptual Metaphors in Donald Trump’s Political Speeches: Framing his Topics and (Self-)Constructing his Persona. Colloquium: New Philologies 3: 98–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, Rod. 2013. Using Metaphor Analysis: MIP and Beyond. The Qualitative Report 18: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polletta, Francesca, and Jessica Callahan. 2017. Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump era. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 5: 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polletta, Francesca, Pang Ching Bobby Chen, Beth Gharrity Gardner, and Alice Motes. 2011. The Sociology of Storytelling. Annual Review of Sociology 37: 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragglejaz Group. 2007. MIP: A Method for Identifying Metaphorically Used Words in Discourse. Metaphor and Symbol 22: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prorata. 2020. Greece in the Coronavirus Era. The Third Survey. (Η Ελλάδα στην εποχή του κορονοϊού. Η τρίτη έρευνα.). Prorata—The Hub of Public Opinion. April 26. Available online: https://prorata.gr/2020/04/26/i-ellada-stin-epoxi-koronoiou-i-triti-ereyna/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Rafoss, Tore Witsø. 2019. Enemies of freedom and defenders of democracy: The metaphorical response to terrorism. Acta Sociologica 62: 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, Saggoo. 2020. Master of The Art of Public Speaking—Greatest Lessons from the Greatest Speeches in History. Edited by Saggoo Raj and K. Singh. New Delhi: Pep Talk India. Available online: https://www.peptalkindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/master-the-art-of-public-speaking.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Rajandran, Kumaran. 2020. ‘A Long Battle Ahead’: Malaysian and Singaporean Prime Ministers Employ War Metaphors for COVID-19. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 20: 261–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaie, Elisabeth El. 2003. Understanding visual metaphor: The example of newspaper cartoons. Visual Communication 2: 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. 2020. Greece Has Won a Battle against COVID-19 but War Is Not Over: PM. Reuters.com. April 13. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-greece-pm-idUSKCN21V1U2 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Richardson, Julia, and Michael B. Arthurs. 2013. “Just Three Stories”: The Career Lessons Behind Steve Jobs ‘ Stanford University Commencement Address. Journal of Business Management 19: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert, William E. 1977. Winston Churchill’s archetypal metaphors: A mythopoetic translation of World War II. Central States Speech Journal 28: 106–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, Hans G. 2017. The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research 10: 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. 2002. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rossolatos, George. 2020. A brand storytelling approach to COVID-19’s terrorealization: Cartographing the narrative space of a global pandemic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 18: 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosteck, Thomas. 1992. Narrative in Martin Luther King’s I’ve been to the mountaintop. Southern Communication Journal 58: 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runeson, Per, and Martin Höst. 2009. Guidelines for conducting and reporting case study research in software engineering. Empirical Software Engineering 14: 131–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, Carolyn B. 1999. Qualitative methods in empirical studies of software engineering. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 25: 557–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring. 2008. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research. Political Research Quarterly 61: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Edward. 2022. As Ukraine Resists Russian Invasion, Zelensky Demonstrates These Leadership Lessons. Forbes. March 1. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/edwardsegal/2022/03/01/as-ukraine-resists-russian-invasion-zelenskyy-demonstrates-these-leadership-lessons/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Semino, Elena. 2021. “Not Soldiers but Fire-fighters”—Metaphors and COVID-19. Health Communication 36: 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semino, Elena, and Michela Masci. 1996. Politics is Football: Metaphor in the Discourse of Silvio Berlusconi in Italy. Discourse & Society 7: 243–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D. J. 2001. Narrative Patterns, the Perils and Possibilities of Using Story in Organisations. Knowledge Management 4: 1–12. Available online: https://cdn.cognitive-edge.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2001/01/02060254/41-narrative-patterns-perils-and-possibilities-final.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Somers, Margaret R. 1994. The narrative constitution of identity: A relational and network approach. Theory and Society 23: 605–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, Gerard. 2002. Towards a procedure for metaphor identification. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 11: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, Gerard. 2008. The Paradox of Metaphor: Why We Need a Three-Dimensional Model of Metaphor. Metaphor and Symbol 23: 213–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, Gerard J., Aletta G. Dorst, J. Berenike Herrmann, Anna A. Kaal, and Tina Krennmayr. 2010. Metaphor in usage. Cogl 21: 765–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetser, Eve. 1990. From Etymology to Pragmatics: Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Steven S., Dalmar Fisher, and Ronald L. Dufresne. 2002. The Aesthetics of Management Storytelling. Management Learning 33: 313–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To Vima. 2019. Remembering Zolotas: A Speech in English with All Greek Words. To Vima (International). Available online: https://www.tovima.gr/2019/03/28/international/remembering-zolotas-a-speech-in-english-with-all-greek-words/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Toader, Florenţa, and Cătălina Grigoraşi. 2016. Storytelling in Online Political Communication during the Presidential Elections Campaign in Romania. Journal of Media Research 26: 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- US National Archives. 2013. US President Obama Whitehouse Archives. Available online: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Vail, Mark. 2006. The “Integrative” Rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” Speech. Rhetoric & Public Affairs 9: 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laer, Tom, Stephanie Feiereisen, and Luca M. Visconti. 2019. Storytelling in the digital era: A meta-analysis of relevant moderators of the narrative transportation effect. Journal of Business Research 96: 135–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mulken, Margot, Andreu van Hooft, and Ulrike Nederstigt. 2014. Finding the Tipping Point: Visual Metaphor and Conceptual Complexity in Advertising. Journal of Advertising 43: 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl E. 2000. Making Sense of the Organization. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, John. 2015. Political Discourse. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 775–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Deirdre, and Robyn Carston. 2006. Metaphor, relevance and the “emergent property” issue. Mind and Language 21: 404–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Deirdre, and Robyn Carston. 2007. Metaphor and the “Emergent Property” Problem: A Relevance-Theoretic Approach. Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication 3: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Qiang. 2016. A Rhetorical Identification Analysis of English Political Public Speaking: John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address. International Journal of Language and Linguistics 4: 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subtypes of Conceptual Metaphors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Structural | Orientational | Ontological | Absolute | Extended | Dead (Cliché) | Sum (All) |

| 29/2/2020 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 11/3/2020 | - | - | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 14/3/2020 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 17/3/2020 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 6 | - | 25 |

| 19/3/2020 | 5 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 9 |

| 22/3/2020 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | - | 16 |

| 27/3/2020 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | - | 3 | 7 |

| 13/4/2020 | 5 | - | 4 | 1 | 1 | - | 11 |

| 19/4/2020 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| 28/4/2020 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 5 |

| 24/9/2020 | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| 20/10/2020 | 2 | - | 2 | - | 2 | - | 6 |

| 31/10/2020 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 13 |

| 17/11/2020 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 31/12/2020 | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| 9/2/2021 | 3 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 6 |

| 4/3/2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 25/3/2021 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| 21/4/2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| 1/5/2021 | - | - | - | 2 | 3 | - | 5 |

| 23/9/2021 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Total * | 43 | 6 | 37 | 18 | 30 | 19 | 153 |

| Average ** | 2.05 | 0.29 | 1.76 | 0.86 | 1.43 | 0.90 | 7.29 |

| % *** | 28.1% | 3.9% | 24.2% | 11.8% | 19.6% | 12.4% | 100% |

| Subtypes of Theme-Based Metaphors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | War | Religious | Game & Sport | Sum (All) |

| 29/2/2020 | - | - | - | - |

| 11/3/2020 | 1 | 2 | - | 3 |

| 14/3/2020 | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| 17/3/2020 | 15 | - | - | 15 |

| 19/3/2020 | 5 | - | - | 5 |

| 22/3/2020 | 3 | - | - | 3 |

| 27/3/2020 | - | - | - | - |

| 13/4/2020 | 2 | 5 | - | 7 |

| 19/4/2020 | - | 5 | - | 5 |

| 28/4/2020 | 2 | - | - | 2 |

| 24/9/2020 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| 20/10/2020 | 2 | - | - | 2 |

| 31/10/2020 | 2 | - | 1 | 3 |

| 17/11/2020 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| 31/12/2020 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| 9/2/2021 | - | - | - | - |

| 4/3/2021 | - | - | - | - |

| 25/3/2021 | - | - | - | - |

| 21/4/2021 | 2 | - | - | 2 |

| 1/5/2021 | - | - | - | - |

| 23/9/2021 | - | - | - | - |

| Total * | 37 | 13 | 1 | 51 |

| Average ** | 1.76 | 0.62 | 0.05 | 2.43 |

| % *** | 24.2% | 8.5% | 0.7% | 33.3% |

| Metaphors | Storytelling | Total (Metaphors & Stories) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Theme-Based | Non-Theme-Based | Sum | Negative | Positive | Sum | |

| 29/2/2020 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| 11/3/2020 | 3 | 3 | 6 | - | - | - | 6 |

| 14/3/2020 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 17/3/2020 | 15 | 10 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 27 |

| 19/3/2020 | 5 | 4 | 9 | - | - | - | 9 |

| 22/3/2020 | 3 | 13 | 16 | - | - | - | 16 |

| 27/3/2020 | - | 7 | 7 | 1 | - | 1 | 8 |

| 13/4/2020 | 7 | 4 | 11 | - | - | - | 11 |

| 19/4/2020 | 5 | 4 | 9 | - | - | - | 9 |

| 28/4/2020 | 2 | 3 | 5 | - | - | - | 5 |

| 24/9/2020 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | - | 2 | 10 |

| 20/10/2020 | 2 | 4 | 6 | - | - | - | 6 |

| 31/10/2020 | 3 | 10 | 13 | - | - | - | 13 |

| 17/11/2020 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | 3 |

| 31/12/2020 | 1 | 10 | 11 | - | 3 | 3 | 14 |

| 9/2/2021 | - | 6 | 6 | - | - | - | 6 |

| 4/3/2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 25/3/2021 | - | 6 | 6 | - | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| 21/4/2021 | 2 | 3 | 5 | - | - | - | 5 |

| 1/5/2021 | - | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 23/9/2021 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Total | 51 | 102 | 153 | 6 | 8 | 14 | 167 |

| Average * | 2.43 | 4.86 | 7.29 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 7.95 |

| % ** | 30.5% | 61.1% | 91.6% | 3.6% | 4.8% | 8.4% | 100% |

| Date | Containment Measures |

|---|---|

| 27 February 2020 | Cancellation of all (Clean Monday/Halloween) carnival festivities |

| 9 March 2020 | Cancellation of big events of more than 1000 people, sports events, and school trips; suspension of all flights to and from northern Italy |

| 10 March 2020 | Closure of all educational establishments |

| 12 March 2020 | Closure of all lawcourts, theatres, cinemas, clubs, gyms, and playgrounds |

| 13 March 2020 | Closure of all museums, archaeological sites, sports facilities, shopping centers, cafes, bars, and restaurants—except for supermarkets, pharmacies, and food stores offering take-away or delivery |

| 14 March 2020 | Suspension of all flights to and from Italy; closure of all organized beaches and ski resorts |

| 16 March 2020 | Suspension of all services in areas of religious worship of any religion or dogma; closure of retail shops; closure of borders with and suspension of all flights to and from Albania and North Macedonia; suspension of all flights to and from Spain; prohibition on all cruise ships and sailboats docking in Greek ports; imposition of 14-day home quarantine on those entering the country |

| 18 March 2020 | Imposition of special restrictions on migrant camps and facilities in regard to movement and visitors; ban on public gatherings of more than ten people and imposition of 1000 euros fine on violators; closure of external borders—in common with EU member-states—to non-EU nationals |

| 21 March 2020 | Restriction on travel to the islands—except for permanent residents and supply trucks |

| 22 March 2020 | Closure of all hotels—except three each in Athens and Thessaloniki and one per regional unit; closure of all parks, recreation areas, and marinas |

| 23 March 2020 | Imposition of total lockdown and restriction on all non-essential movement throughout the country—the imposition of 150 euros fine on violators; suspension of all flights to and from the UK and Turkey |

| 28 March 2020 | Suspension of all flights to and from Germany and the Netherlands |

| 4 April 2020 | Extension of lockdown until 27 April |

| 23 April 2020 | Extension of lockdown until 4 May |

| 20 October 2020 | The use of masks becomes mandatory everywhere and there is a prohibition of standing in indoor halls |

| 31 October 2020 | The territory is divided into two zones: Surveillance and Increased Risk. Use of masks everywhere, indoors, and outdoors. Restriction of traffic from 12:00 at night to 5:00 in the morning. Implement teleworking 50% in the public and private sectors. And full tele-education in universities. In the Increased Risk Zone Suspension of the operation of all catering premises, places of entertainment, culture, and sport |

| 28 February 2021 | Additional measures in high-risk zones with the closure of all retail outlets and distance learning at all levels. |

| 3 May 2021 | Gradual lifting of the measures. Outdoor dining reopens |

| 10 May 2021 | Secondary and primary schools reopen |

| 15 May 2021 | Tourism opens |

| Subtypes of Conceptual Metaphors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place & Title of Speech | Structural | Orientational | Ontological | Absolute | Extended | Dead (Cliché) | Sum (All) |

| 8/3/2022 | Address by the President of Ukraine to the Parliament of the United Kingdom | 3 | - | 2 | - | - | - | 5 |

| 11/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Sejm of the Republic of Poland | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 4 |

| 12/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to Italians and all Europeans | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 3 |

| 15/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Parliament of Canada | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 16/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to the US Congress | 4 | - | 4 | 1 | 1 | - | 10 |

| 17/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to the Bundestag | - | 4 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 |

| 19/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to the people of Switzerland | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 23/3/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine at a joint meeting of the Senate, the National Assembly of the French Republic, and the Council of Paris | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 3 |

| 23/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Parliament of Japan | 2 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 5 |

| 24/3/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine at the Riksdag in Sweden | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 29/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in Folketing (Denmark) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 3 | 5 |

| 30/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Norwegian Storting | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 31/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the States General of the Netherlands | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 5 |

| 31/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Australian Parliament | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 6 |

| 4/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Romanian Parliament | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 5/4/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine in the Cortes Generales of Spain | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 4 |

| 7/4/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine in the House of Representatives of Cyprus | - | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 3 |

| 7/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Parliament of Greece | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 3 |

| 8/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in Eduskunta, the Parliament of Finland | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2 |

| 11/4/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine in the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea | 2 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 13/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Riigikogu, Estonian Parliament | 3 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 |

| 21/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Assembly of the Republic, Parliament of Portugal | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 4 |

| 26/5/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Saeima of Latvia | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 4 |

| 27/5/2022 | President of Ukraine addressed the citizens of Belarus | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 31/5/2022 | President of Ukraine address to the Parliament of Belgium | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 4 |

| Total * | 31 | 10 | 19 | 9 | 19 | 14 | 102 | |

| Average ** | 1.24 | 0.4 | 0.76 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 4.08 | |

| % *** | 30.4% | 9.8% | 18.6% | 8.8% | 18.6% | 13.7% | 100% | |

| Metaphors | Storytelling | Total (Metaphors & Stories) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Negative | Positive | Sum | |||

| 8/3/2022 | Address by the President of Ukraine to the Parliament of the United Kingdom | 5 | 1 | - | 1 | 6 |

| 11/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Sejm of the Republic of Poland | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| 12/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to Italians and all Europeans | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| 15/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Parliament of Canada | 0 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 |

| 16/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to the US Congress | 10 | 2 | - | 2 | 12 |

| 17/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to the Bundestag | 5 | - | - | - | 5 |

| 19/3/2022 | Address by President of Ukraine to the people of Switzerland | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 23/3/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine at a joint meeting of the Senate, the National Assembly of the French Republic, and the Council of Paris | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | 4 |

| 23/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Parliament of Japan | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 24/3/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine at the Riksdag in Sweden | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| 29/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in Folketing (Denmark) | 5 | 1 | - | 1 | 6 |

| 30/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Norwegian Storting | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 31/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the States General of the Netherlands | 5 | 1 | - | 1 | 6 |

| 31/3/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Australian Parliament | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 7 |

| 4/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Romanian Parliament | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| 5/4/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine in the Cortes Generales of Spain | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| 7/4/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine in the House of Representatives of Cyprus | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | 4 |

| 7/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Parliament of Greece | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 8/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in Eduskunta, the Parliament of Finland | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | 3 |

| 11/4/2022 | Speech by the President of Ukraine in the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| 13/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Riigikogu, Estonian Parliament | 5 | - | - | 0 | 5 |

| 21/4/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Assembly of the Republic, Parliament of Portugal | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| 26/5/2022 | Speech by President of Ukraine in the Saeima of Latvia | 4 | - | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 27/5/2022 | President of Ukraine addressed the citizens of Belarus | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| 31/5/2022 | President of Ukraine address to the Parliament of Belgium | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 102 | 27 (75% **) | 9 (25% **) | 36 (100% **) | 138 | |

| Average * | 4.08 | 1.08 | 0.36 | 1.44 | 5.52 | |

| % *** | 73.9% | 19.6% | 6.5% | 26.1% | 100% | |

| Date | Progress and Events of the Conflict |

|---|---|

| February 2022 | The invasion begins:

|

| March 2022 | Shockwaves from the invasion reverberate around the world:

|

| April 2022 | A new phase of war:

|

| May 2022 | NATO grows:

|

| June 2022 | 100 days of war:

|

| July 2022 | Russia advances in the East:

|

| August 2022 | Gas exports to Europe stop:

|

| September 2022 | Mobilization:

|

| October 2022 | Sabotage:

|

| November 2022 | Kherson recaptured by Ukraine troops:

|

| December 2022 | Grim warnings for spring:

|

| January 2023 | Tanks, tanks, tanks:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkalitsiou, K.; Kotsopoulos, D. When the Going Gets Tough, Leaders Use Metaphors and Storytelling: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Communication in the Context of COVID-19 and Ukraine Crises. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040110

Gkalitsiou K, Kotsopoulos D. When the Going Gets Tough, Leaders Use Metaphors and Storytelling: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Communication in the Context of COVID-19 and Ukraine Crises. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(4):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040110

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkalitsiou, Katerina, and Dimosthenis Kotsopoulos. 2023. "When the Going Gets Tough, Leaders Use Metaphors and Storytelling: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Communication in the Context of COVID-19 and Ukraine Crises" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 4: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040110

APA StyleGkalitsiou, K., & Kotsopoulos, D. (2023). When the Going Gets Tough, Leaders Use Metaphors and Storytelling: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Communication in the Context of COVID-19 and Ukraine Crises. Administrative Sciences, 13(4), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040110