Coping with Dark Leadership: Examination of the Impact of Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Dark Leaders and Employees’ Basic Need Satisfaction in the Workplace

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Dark Triad of Personality and Destructive Leadership

2.2. Self-Determination Theory and Basic Need Satisfaction

2.3. Psychological Capital

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dark Triad of Personality

3.2.2. Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction

3.2.3. Psychological Capital

3.3. Avoidance of Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

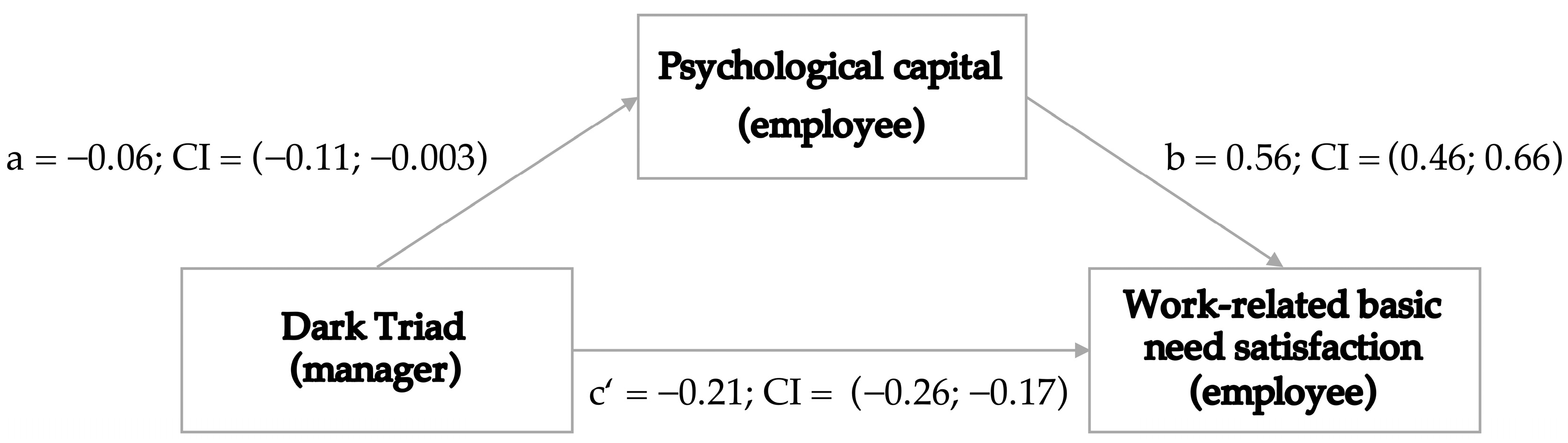

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

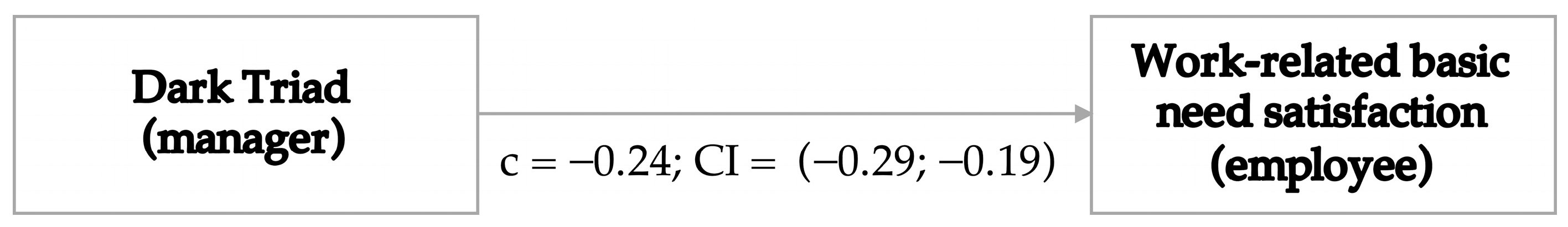

| Predictors | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta (β) | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 5.88 | 0.08 | 71.22 | <0.001 | |

| Dark Triad (manager) | −0.24 | 0.03 | −0.41 | −9.68 | <0.001 |

| Predictors | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta (β) | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 5.58 | 0.09 | 71.80 | <0.001 | |

| Dark Triad (manager) | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −2.45 | 0.04 |

| Predictors | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta (β) | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 2.14 | 0.28 | 8.36 | <0.001 | |

| Psychological capital (employee) | 0.56 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 11.95 | <0.001 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avey, James B., Fred Luthans, and Carolyn M. Youssef. 2010. The Additive Value of Positive Psychological Capital in Predicting Work Attitudes and Behaviors. Journal of Management 36: 430–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avey, James B., Rebecca J. Reichard, Fred Luthans, and Ketan H. Mhatre. 2011. Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Positive Psychological Capital on Employee Attitudes, Behaviors, and Performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly 22: 127–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baard, Paul P., Edward L. Deci, and Richard M. Ryan. 2004. Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of Performance and Well-Being in Two Work Settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34: 2045–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, Richard W. 1970. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1: 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, William Keith, Brian J. Hoffman, Stacy M. Campbell, and Gaia Marchisio. 2011. Narcissism in Organizational Contexts. Human Resource Management Review 21: 268–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, Richard, and Florence L. Geis. 1970. Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cribari-Neto, Francisco. 2004. Asymptotic Inference under Heteroskedasticity of Unknown Form. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 45: 215–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drory, Amos, and Uri M. Gluskinos. 1980. Machiavellianism and Leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology 65: 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, Ståle, Merethe Schanke Aasland, and Anders Skogstad. 2007. Destructive Leadership Behaviour: A Definition and Conceptual Model. Leadership Quarterly 18: 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbers, Alina, Stephan Kolominski, and Pablo Salvador Blesa Aledo. 2022. Destructive Leadership in Organizations: Studies on the Impact of the Dark Triad of Personality Using an Employee-Centered Approach. Paper presented at VIII Jornadas de Investigación y Doctorado “Ética En La Investigación Científica, Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), Murcia, Spain, June 24. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, Adrian, Steven C. Richards, and Delroy L. Paulhus. 2013. The Dark Triad of Personality: A 10 Year Review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 7: 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, Marylène, Jacques Forest, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Laurence Crevier-Braud, Anja Van den Broeck, Ann Kristin Aspeli, Jenny Bellerose, Charles Benabou, Emanuela Chemolli, Stefan Tomas Güntert, and et al. 2014. The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale: Validation Evidence in Seven Languages and Nine Countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 24: 178–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2022. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Li Cai. 2007. Using Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Standard Error Estimators in OLS Regression: An Introduction and Software Implementation. Behavior Research Methods 39: 709–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hogan, Robert, and Robert B. Kaiser. 2005. What We Know about Leadership. Review of General Psychology 9: 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, Joshua, Marylène Gagné, Alexandre J. S. Morin, and Anja Van den Broeck. 2016. Motivation Profiles at Work: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior 95–96: 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jonason, Peter Karl, and Gregory D. Webster. 2010. The Dirty Dozen: A Concise Measure of the Dark Triad. Psychological Assessment 22: 420–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, Daniel Nelson, and Delroy L. Paulhus. 2014. Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A Brief Measure of Dark Personality Traits. Assessment 21: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, Barbara. 2004. Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Krasikova, Dina V., Stephen G. Green, and James M. LeBreton. 2013. Destructive Leadership: A Theoretical Review, Integration, and Future Research Agenda. Journal of Management 39: 1308–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küfner, Albrecht C. P., Michael Dufner, and Mitja D. Back. 2014. Das Dreckige Dutzend Und Die Niederträchtigen Neun: Kurzskalen Zur Erfassung von Narzissmus, Machiavellismus Und Psychopathie. Diagnostica 61: 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kibeom, Michael C. Ashton, Jocelyn Wiltshire, Joshua S. Bourdage, Beth A. Visser, and Alissa Gallucci. 2013. Sex, Power, and Money: Prediction from the Dark Triad and Honesty-Humility. European Journal of Personality 27: 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, Dominik J. 2019. Too Fast, Too Straight, Too Weird: Non-Reactive Indicators for Meaningless Data in Internet Surveys. Survey Research Methods 13: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, Timo, Clemens Beer, Jan Pütz, and Kathrin Heinitz. 2016. Measuring Psychological Capital: Construction and Validation of the Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12). PLoS ONE 11: e0152892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luthans, Fred. 2002. The Need for and Meaning of Positive Organizational Behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 23: 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, Fred, Carolyn M. Youssef, and Bruce J. Avolio. 2007. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, Fred, Steven M. Norman, Bruce J. Avolio, and James B. Avey. 2008. The Mediating Role of Psychological Capital in the Supportive Organizational Climate—Employee Performance Relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior 29: 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathieu, Cynthia, Craig S. Neumann, Robert D. Hare, and Paul Babiak. 2014. A Dark Side of Leadership: Corporate Psychopathy and Its Influence on Employee Well-Being and Job Satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences 59: 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Alexander, Deniz Ucbasaran, Fei Zhu, and Giles Hirst. 2014. Psychological Capital: A Review and Synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35: S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, Ernest Hugh, Donelson Ross Forsyth, George C. Banks, and Michael A. McDaniel. 2012. A Meta-Analysis of the Dark Triad and Work Behavior: A Social Exchange Perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology 97: 557–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, Art, Robert Hogan, and Robert B. Kaiser. 2007. The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers, and Conducive Environments. Leadership Quarterly 18: 176–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, Delroy L., and Kevin M. Williams. 2002. The Dark Triad of Personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality 36: 556–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Suzanne J., and Fred Luthans. 2003. The Positive Impact and Development of Hopeful Leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 24: 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip Michael, Scott B. MacKenzie, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2012. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 539–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rauthmann, John F., and Gerald P. Kolar. 2012. How ‘Dark’ Are the Dark Triad Traits? Examining the Perceived Darkness of Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences 53: 884–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, Derek D., Kristopher J. Preacher, Zakary L. Tormala, and Richard E. Petty. 2011. Mediation Analysis in Social Psychology: Current Practices and New Recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5: 359–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, Birgit, and Jan Schilling. 2013. How Bad Are the Effects of Bad Leaders? A Meta-Analysis of Destructive Leadership and Its Outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly 24: 138–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, Nicola, Niamh Hickey, Nicolaas Blom, Liam O’Mahony, and Patricia Mannix-McNamara. 2021. An Exploration of Leadership in Post-Primary Schools: The Emergence of Toxic Leadership. Societies 11: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, Seth M., Peter Harms, and James M. Lebreton. 2014. The Dark Side of Personality at Work. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35: S41–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stajkovic, Alexander D., and Fred Luthans. 1998. Self-Efficacy and Work-Related Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin 124: 240–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Mark. 2013. When Does Narcissistic Leadership Become Problematic? Dick Fuld at Lehman Brothers. Journal of Management Inquiry 22: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, Bennett J. 2000. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Academy of Management Journal 43: 178–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, Anja, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Hans de Witte, Bart Soenens, and Willy Lens. 2010. Capturing Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness at Work: Construction and Initial Validation of the Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83: 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webster, Vicki, Paula Brough, and Kathleen Daly. 2016. Fight, Flight or Freeze: Common Responses for Follower Coping with Toxic Leadership. Stress and Health 32: 346–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, Carolyn M., and Fred Luthans. 2007. Positive Organizational Behavior in the Workplace: The Impact of Hope, Optimism, and Resilience. Journal of Management 33: 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dark Triad (manager) | 2.95 | 1.49 | (0.95) | ||

| 2. Psychological capital (employee) | 5.41 | 0.76 | −0.11 * | (0.86) | |

| 3. Work-related basic need satisfaction (employee) | 5.17 | 0.88 | −0.41 ** | 0.48 ** | (0.89) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elbers, A.; Kolominski, S.; Blesa Aledo, P.S. Coping with Dark Leadership: Examination of the Impact of Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Dark Leaders and Employees’ Basic Need Satisfaction in the Workplace. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040096

Elbers A, Kolominski S, Blesa Aledo PS. Coping with Dark Leadership: Examination of the Impact of Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Dark Leaders and Employees’ Basic Need Satisfaction in the Workplace. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(4):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040096

Chicago/Turabian StyleElbers, Alina, Stephan Kolominski, and Pablo Salvador Blesa Aledo. 2023. "Coping with Dark Leadership: Examination of the Impact of Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Dark Leaders and Employees’ Basic Need Satisfaction in the Workplace" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 4: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040096

APA StyleElbers, A., Kolominski, S., & Blesa Aledo, P. S. (2023). Coping with Dark Leadership: Examination of the Impact of Psychological Capital on the Relationship between Dark Leaders and Employees’ Basic Need Satisfaction in the Workplace. Administrative Sciences, 13(4), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040096