1. Introduction

Disruptive innovation is a widely applied concept that describes how innovation disrupts an existing industry. First introduced by Christensen in 1997, this concept has received popular attention from managers across industries as well as several scholars. In particular, incumbent responses to disruptive innovation have garnered much attention from both managers and scholars, as a simple act of innovation can shift the dynamics of an entire extant industry. However, several aspects of incumbent responses have not been sufficiently investigated. Among the numerous case studies on the success or failure of incumbent responses to disruptive innovation, studies have tended to focus on the phenomenon of disruptive innovation itself to analyze the outcome of the firm’s decision, leaving out the implications of the decision-making processes undertaken by the firm. However, each firm possesses various characteristics that lead to different outcomes. Thus, this study aims to identify the factors influencing the decision-making processes of incumbent firms when responding to disruptive innovation, with a focus on the role of CEOs.

This study narrows the scope of the investigation to a subset of the South Korean retail industry, wherein a few traditional retail incumbents have dominated the market over years. This domination by a select group of retail conglomerates has resulted in firms sharing a stable expansion in the market. However, the South Korean retail industry has also demonstrated dynamic evolution. With the advent of technology, the e-commerce market has grown exponentially, taking over the growth of the traditional retail market. Along with changing markets, a new kind of disruptive innovation has emerged, with the retail startup Coupang shifting the market paradigm to focus on faster delivery and logistics. With such rapid changes in the market, traditional retail conglomerates, who enjoyed great success in the offline retail era, have now become burdened with the task of responding to innovation. Considering this dynamic environment, studying the South Korean retail industry in the context of disruptive innovation is particularly relevant. In particular, this study explores the response of Lotte, a traditional retail giant in the South Korean retail industry. While other incumbents and competitors responded to Coupang’s disruptive innovation by adapting to provide faster delivery, Lotte, as an incumbent, attempted to differentiate itself from the innovation in question. Therefore, Lotte launched Lotte-ON in an attempt to survive in an ever-changing environment. In this regard, Lotte’s counter-move led to the following question: “What are the sources of varied incumbent responses to disruptive innovation?” To that end, this study analyzes this phenomenon and the specific aspects that led to Lotte’s decision-making process.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section explores the existing literature on disruptive innovation and strategies for incumbent responses. The subsequent section briefly outlines the methodology used in this research. Next, the history of Lotte is explained to establish how it became an incumbent. Disruptive innovation in the South Korean retail industry is analyzed to illustrate the changing paradigms in the industry. This study further conducts a qualitative case analysis of Lotte and uses an in-depth case study approach to explore the causes of Lotte’s challenges in responding to disruptive innovation. Based on this analysis, this study argues that a key factor that influences the incumbent’s responses to disruptive innovation is CEO attention: the discretion of the CEO leads to the overall decision of the firm. Therefore, this research contributes to the understanding of how CEO attention shapes incumbent responses to disruptive innovation and has implications for managerial decision making in the face of rapidly changing market dynamics.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Understanding Disruptive Innovation

Disruptive innovation refers to the process by which a smaller, inferior company, usually with fewer resources, moves upmarket and challenges larger, established businesses (

Christensen 1997). Christensen explains that the process of disruptive innovation starts with innovators finding a niche and emerging market and then making it appealing to mainstream consumers, thus establishing a new market (

Bower and Christensen 1995). As a result, their value proposition is usually considered inferior to that of existing incumbents, who already have a strong presence in existing markets. However, when the entrant improves its innovation’s performance over time, it can easily attack incumbents, as existing incumbents downplay the threat from downmarket at first (

Bower and Christensen 1995). Disruption occurs when mainstream customers begin to accept and purchase the entrant’s offering in volume (

Petzold et al. 2019).

Not all groundbreaking and radical innovations are disruptive. For one, radical innovations originate from fresh knowledge and the introduction of entirely new ideas or products into the market. Consequently, studies on radical innovation concentrate on understanding the organizational behaviors and structures that elucidate and forecast the successful implementation of groundbreaking concepts (

Hopp et al. 2018). Yet, the more radical the innovation, estimating its market acceptance and potential becomes more difficult (

Assink 2006). Instead of directly comparing the innovations, two different types of technological innovation are suggested. First, sustaining technologies improve the performance of existing products, keeping them close to the needs of current customers (

Christensen 1997). On the other hand, disruptive innovation introduces different sets of attributes in a low-end or new market (

Christensen et al. 2015). Equipped with high-cost structures, disruptive technologies look unattractive to incumbents at first, as incumbents more widely implement sustainable technologies and opt to enter into markets with higher profit margins (

Bower and Christensen 1995). Incumbents want their resources to be allocated to their primary activities that promise higher profits. The difference between the two technologies is further emphasized when observing the early adopters of each technology. Early adopters of disruptive innovations possess more in-depth knowledge of the product category, whereas early adopters of sustaining products do not feel any more knowledgeable than late adopters (

Reinhardt and Gurtner 2015).

Disruptive innovation is not a definite process; rather, it depends on the business structure of each firm, suggesting that a given instance of disruptive innovation can be disruptive to some but sustainable to others (

Christensen et al. 2018).

Danneels (

2004) perceives the process of disruptive innovation differently, stating that disruptive technology changes the way firms compete by changing performance metrics.

Danneels (

2004) offers a similar definition of new innovations as having different attributes to existing products and services that have lower performance in the mainstream market but higher performance in the emerging market. Over time, entrants’ performances meet the minimum demand of the mainstream market, introducing a new dimension of competition to incumbents in the mainstream market (

Danneels 2004).

Despite its widespread popularity, there has been much criticism of disruptive innovation, with many using the term in an inaccurate way by applying the concept in a vague manner to refer to any new threat (

Christensen et al. 2018). Christensen addressed this issue and clarified the popular theory by clearly stating that disruptive innovation does not apply to every act of innovation, but that it starts out as a process. He also points out two important factors that define the disruptive innovation process: (1) disruptive innovation starts from a low-end or an emerging market and (2) disruptive innovation only enters the mainstream market when quality catches mainstream consumers (

Christensen et al. 2015). Further, he notes that not every innovation is inherently disruptive (

Christensen et al. 2018) and not every disruptive product or service is innovative. For example, Uber, a popular transportation application that is well associated with being innovative, does not fit the category of disruptive innovation, as it neither started from a low-end or emerging market nor was it inferior compared to the mainstream market when it was first launched (

Christensen et al. 2015).

2.2. Incumbent Responses to Innovation

The literature on disruptive innovation has great significance for managers because it studies potential changes in an organization. Incumbents often overlook such changes, as their primary interest and investments are directed towards the needs and wants of current and existing customers (

Christensen et al. 2015). However, as disruptive innovators enter the mainstream market, sometimes becoming superior, established incumbents notice the emergent changes and begin finding ways to respond to it (

Markides 2006). Christensen argues that to respond to change, incumbents first need to assess their organizational capabilities and incapability and then choose to either sustain or destroy their existing resources, processes, and values (

Christensen and Overdorf 2000). As such, disruptive innovation poses a crucial dilemma: adapting to a new change or sustaining existing business practices (

Markides 2006). In

The Innovator’s Dilemma,

Christensen (

1997) offers frameworks for guiding managers for when they are responding to disruptive innovation.

In his first approach, Christensen (

Christensen and Overdorf 2000) suggested creating new capabilities internally, forming what is called a “heavyweight team” (

Clark and Wheelwright 1992) within the existing mainstream organization. Requiring different people, interactions, and activities, such teams are suitable when the new change does not fit the existing process of the organization (

Christensen and Overdorf 2000). If the innovation requires a completely different set of processes and values, then a separate spinout organization is more suitable, as large, established firms are incapable of allocating resources to emerging markets where disruption first begins. It is important to note that a spin-off needs to be an entirely separate unit from the existing businesses; thus, an incumbent must run two businesses simultaneously, being careful enough to prevent one business from cannibalizing the other (

Christensen and Overdorf 2000). The last framework suggested by Christensen involves paying for new capabilities through mergers and acquisitions, where the new organization’s integration into the parent company’s existing process and values can create another challenge (

Christensen and Overdorf 2000).

However, the response to change can take several forms when approaching disruptive innovation. Markides and Charitou do not restrict incumbents’ responses to adoption only; rather, they set out a broader response level than Christensen (

Markides and Charitou 2004). By setting motivation and ability to respond to disruptive innovation as the two factors that influence an incumbent firm’s response, Markides and Charitou showcase five responses that firms take when faced with innovation. The first response is for firms to focus on their existing core businesses by making traditional practices more competitive and attractive when competing with innovators (

Markides and Charitou 2004). Second, incumbents can simply ignore innovation when the innovator is not in the same target market, thus not recognizing it as a threat (

Markides and Charitou 2004). Incumbents can play a “third game”, developing a different set of business attributes to attack disruptive innovators. Other responses include adopting or embracing innovation internally, either by creating a separate spinoff unit while keeping the existing business, or by completely embracing the innovation and abandoning the existing business (

Markides and Charitou 2004). Gilbert provides further support for this analysis, as his study of newspaper firms shows that one newspaper incumbent was able to remain in market leadership by launching a structurally differentiated venture (

Gilbert 2005).

Another aspect of this dilemma is whether to explore or exploit. Based on the concept of exploration and exploitation in organizational learning, Osiyevskyy and Dewald state that incumbent managers have two general ways of responding to disruptive innovation: (1) exploring new innovations and adopting them; or (2) exploiting existing business practices by making them more competitive (

Osiyevskyy and Dewald 2015). Within the two generic ways of responding, he further divides exploration and exploitation into four typologies: (1) pure exploration, wherein a firm adopts innovation; (2) integration, wherein the company integrates the innovation internally or creates a spinoff unit while maintaining existing practices; (3) defiant resistance to innovation, wherein managerial positions defend existing business routines; and (4) pure exploitation to strengthen existing routines without adapting to change (

Osiyevskyy and Dewald 2015).

In the mentioned approaches, responding to disruptive innovation begins with first assessing the firm’s internal capacity, that is, the core competencies of the firm. In doing so, however, firms need to consider once again if their core competency is fit to respond to the innovation. Core competency of an incumbent may turn into core rigidity in a new environment presented by disruptive innovation. Existing business practices that led to the incumbent’s previous success may become a static business model that hinders innovation (

Yang et al. 2022). Accordingly, timely response to disruptive innovation plays a key success factor. According to Yang, Kim, and Choi, the “routine rigid” approach that the incumbent takes results in the firm falling behind. Similarly, Florian, Juan, and Abhinav also suggest that incumbent firms need to act fast in efforts to adapt to disruptive innovation in the tourism industry. While incumbents have taken diligence in responding to disruptive innovation, this has led to a negative impact on the market value, strongly implying that more resources needed to be allocated to respond faster to disruptive innovation (

Zach et al. 2020).

2.3. CEO Attention in Responding to Disruptive Innovation

An important question arises with respect to the direction that incumbents need to take when responding to disruptive innovation. According to the existing theories on incumbent responses, organizations need to carefully calculate what method to choose. This study then argues that CEO decisions play a key role in deciding which method is selected to respond to disruptive innovation. According to Hambrick and Mason’s upper echelon theory (UET), the personal perception and cognition of the CEO are highly influential in determining a firm’s strategic choice (

Hambrick 2007). CEOs are more than just the support structure for a project; their primary role includes setting the firm’s general agenda. More importantly, their focus and attention play a key role in directing the attention of organizational members to a particular area of endeavor. Thus, the decision making of a CEO, particularly where the CEO’s attention lies, is an important matter for a firm’s future direction. This concept is relevant when determining the direction an incumbent firm requires to respond to disruptive innovation. Successful innovation requires a firm to focus on a particular series of tasks, each of which further needs specific attentional resources (

Yadav et al. 2007). These tasks include detection, development, and deployment. In such cases, CEOs have a direct impact on how a firm can “detect, develop, and deploy new technologies over time”. The CEO decides to focus his or her attention on becoming a key provider of direction for the entire firm. Therefore, the way a CEO exercises discretion in allocating attentional resources has significant implications for the firm’s future.

The importance of CEO attention is further amplified in South Korea’s retail environment, where incumbents consist mostly of chaebols. Chaebols are a specific type of business found in South Korea, wherein a single wealthy family controls all parts of the firm, including subsidiaries and affiliates, through a chain of ownership relations (

Park et al. 2020). Chaebols then act as both owners and managers of conglomerates. Accordingly, a chaebol CEO’s decision making is emphasized in a chaebol organization system, especially because chaebol firms lack external monitoring. A chaebol conglomerate’s organizational structure follows a centralized hierarchy controlled by the chaebol family. All chaebol affiliates, called kyeyols, are under the direct control of the chaebol firm’s central planning office, which is virtually controlled by the firm’s owners, who belong to the chaebol family. This makes the chaebol family responsible for the majority of internal monitoring and decision making in the top management (

Park and Yuhn 2012). Owing to the lack of external monitoring, a chaebol CEO’s decisions have more power to influence the future of the firm. Thus, the CEO’s attention becomes the firm’s overarching influencer of direction.

Therefore, this study adds to the discourse on incumbent responses to disruptive innovation by carefully examining the response of the incumbent, Lotte, in the South Korean retail industry. Disruptive innovation does not occur overnight; it takes several years for incumbents to realize this. Lotte was also a late responder to disruptive innovation. This study utilizes previous literature on strategies that incumbents adopt when responding to disruptive innovation to analyze the strategies that Lotte-ON adopted. After further examining why it was doomed to fail, this study reveals that Lotte, in fact, took on an inappropriate approach when responding to disruptive innovation. Thus, this study also acts as a cautionary tale for existing incumbents.

3. Methodology

This case study examines and analyzes incumbent responses to disruptive innovation in the South Korean e-commerce market. Lotte was chosen for this case study because Lotte Group is a prominent retail incumbent in South Korea. Lotte, the largest distribution network in South Korea, recently launched an e-commerce platform in an attempt to respond to the shifting dynamics of the South Korean retail industry, reflecting the emergence of a disruptive innovator. The platform, Lotte-On, was launched in 2020 to high expectations, but was met with unexpected results that did not meet Lotte’s status as a successful incumbent. Thus, Lotte was selected for analysis as an example of an incumbent’s inappropriate response to disruptive innovation in the South Korean retail industry’s competitive environment.

The research employs a case study method that aims to focus on understanding a phenomenon within a single-setting environment (

Eisenhardt 1989). The case study method was deemed appropriate for this research because this study deals with finding answers to technical questions on how and why a phenomenon occurred, based on the research question posed above (

Yin and Aberdeen 2014). In particular, this study utilizes a descriptive case study framework. A descriptive case study describes phenomena within the data being questioned and sets a goal to describe the data as the phenomenon occurs (

Ong et al. 2007). Accordingly, a descriptive case study was considered appropriate for describing an in-depth contemporary phenomenon that occurred in the context of the data being analyzed. Therefore, this study used a single in-depth case of Lotte, allowing for a detailed analysis of the situation experienced by the incumbent firm in response to disruptive innovation. According to

Edmondson and McManus (

2007), these methods are well-suited in answering our research questions because they facilitate exploration by allowing us to initiate a deep dive into the phenomenon (

Edmondson and McManus 2007).

Case studies typically combine data collection methods such as archives, interviews, questionnaires, and observations (

Eisenhardt 1989). To develop the case study, this study used an extensive collection of secondary data by assembling information from various sources. These sources include the company’s investor relations, news articles from various time periods, and business reports gathered from the Data Analysis, Retrieval and Transfer System (DART). This case study also utilized forms of archival data by collecting CEO interviews from various eras, including government agency briefs. Naver and Google search engines were used with assorted search keywords to collect relevant data. By incorporating various sources of data, this study aimed to increase the validity and reliability of the case study. Data triangulation was utilized, in which multiple sources were used in the data-collecting process to examine the research question from different angles. The collected data were then compared and cross-checked by all the authors to promote the credibility of the secondary data sources. With these, the research accumulated pieces of information and data into an organized format and revealed the relevance of disruptive innovation in the South Korean retail industry, and accordingly, the incumbent’s inappropriate response to disruptive innovation. Therefore, the methodology above provides a holistic and meaningful description of the case study of Lotte as an incumbent in the South Korean retail industry.

4. Lotte Shopping’s History and Background

Lotte Group was established by Shin Kyuk-ho, who initially established his business in Japan. Lotte Group is currently one of Korea’s top five conglomerates and operates multiple business units, including confectioneries, food and beverages, petrochemicals, distribution, movies, hotels, leisure, and construction. Among them, Lotte Shopping is Lotte’s distribution business, which operates discount stores, electronics stores, department stores, supermarkets, home shopping, movie sales, and e-commerce. Lotte Shopping has more than 13,000 offline stores in South Korea (

D. Kim 2022).

Lotte Shopping bases its business on Hyeopwoo Industrial Co., Ltd., established on 2 July 1970. The company changed its name to Lotte Shopping on 15 November 1979 to begin operating the distribution business. Lotte Shopping officially established its name with the opening of the Lotte Department Store in Sogong-dong, Jung-gu, Seoul. The headquarters of all Lotte Department Stores opened in December 1979, a month after the launch of Lotte Shopping (

D. Kim 2022). Lotte Shopping further expanded its business to include discount stores and supermarkets at the end of the 1990s. As of the second quarter of 2022, it operates 60 department stores (including the Lotte Shopping Mall and Outlets), 4 overseas department stores, 112 Lotte Marts, 63 overseas Lotte Marts, and 391 Lotte Supers in Korea. The company is also in charge of Lotte Shopping e-commerce, and even merged with Lotte.com in 2018 to strengthen online performance (

Lotte Shopping 2022b).

Lotte-ON was launched in April 2020 in an attempt to bring together Lotte Shopping’s retail affiliates. It launched as an online shopping platform that integrates seven retail affiliates: Lotte Department Store, Lotte Mart, Lotte Super, LOHBs (H&B store), Hi-Mart, Lotte Home Shopping, and Lotte.com (

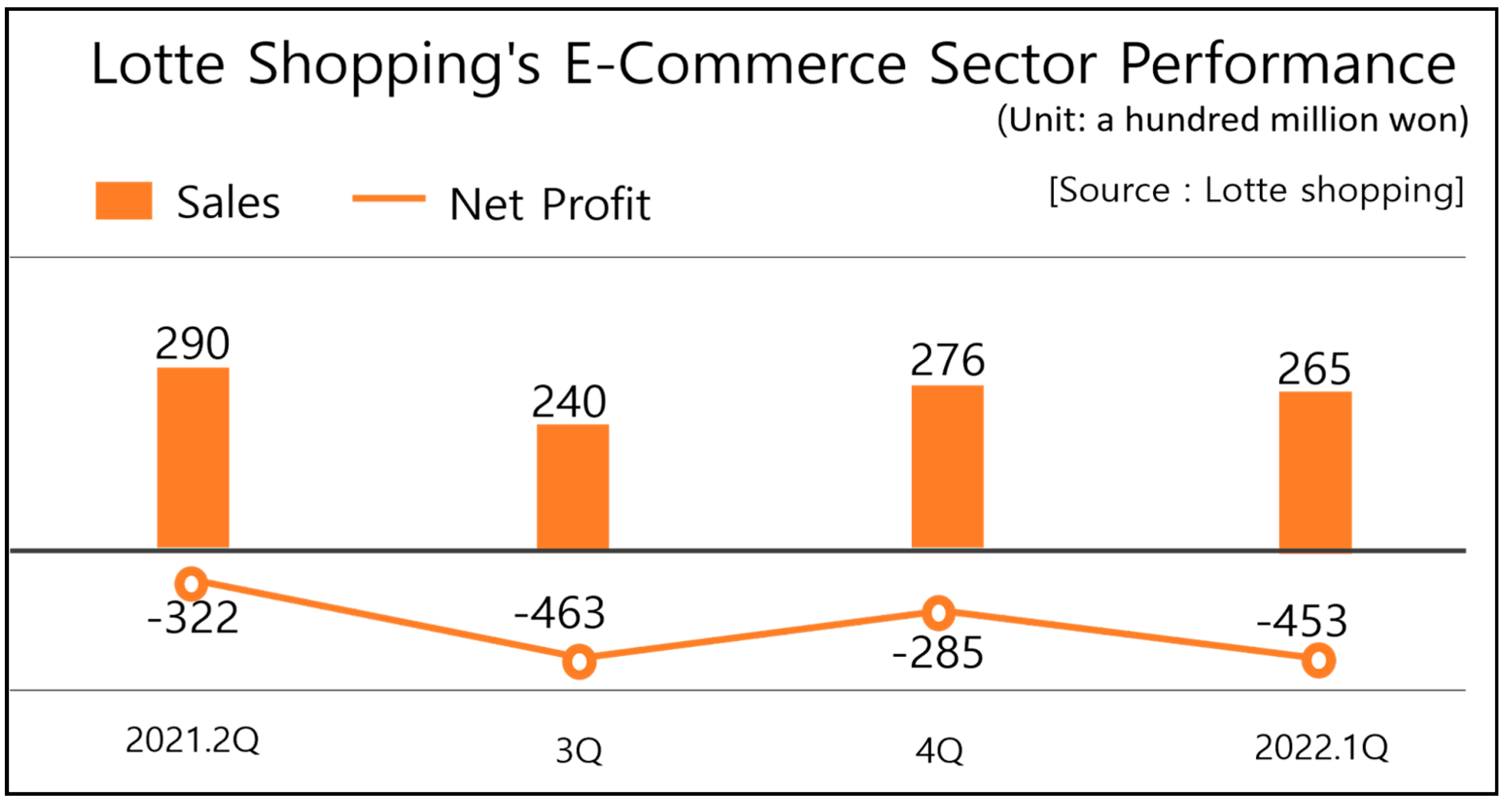

J. Park 2020). Unfortunately, since the launch of Lotte-ON, Lotte Shopping’s e-commerce division has suffered from a continuous operating profit deficit (

Kang 2022). This is further evidenced by Lotte Shopping’s declining performance as shown in

Figure 1 (

Lotte Shopping 2022a). As of 2022, Lotte-ON has withdrawn its early morning delivery service for fresh produce due to continuous and cutthroat competition (

Cho 2022) and decided to focus on boosting competitiveness in fashion, including cosmetics and luxury goods (

B.-k. Shin 2022).

5. Disruptive Innovations in South Korea’s Retail Industry

Disruptive innovation is a process, not a rapid disruption. It follows the path of an emerging inferior firm gradually moving upmarket to reach mainstream status. Thus, disruptive innovation is often difficult to spot and is easily overlooked by incumbents. However, once realized, disruptive innovation may threaten incumbent firms. In the case of disruptive innovation in the South Korean retail industry, it took several years for incumbents to realize that disruption had occurred.

5.1. The Emergence of E-Commerce Marketplace

5.1.1. Shift from Offline to Online Market

There have been two major turning points in South Korea’s retail industry. First, the e-commerce shopping market era shifted the retail paradigm from offline to online. Emerging in 1995, television (TV) home shopping became a boom, enabling consumers to experience shopping without face-to-face interaction when visiting an offline retail store. Various e-commerce shopping sites were also introduced around this time, including the launch of ‘Lotte.com.’ This led to other shopping sites forming hybrid channels with TV home shopping. However, as TV home shopping started to decline in 2002, it paved the way for e-commerce shopping sites to grow (

Lee and Gu 2010).

The second turning point was the advent of the mobile shopping era. With the introduction of smartphone devices, mobile shopping began to rise, soon replacing the popularity of online shopping sites, accounting for 75.5% of all online shopping transactions in January of 2022 (

Statistics Korea 2022). Moreover, online shopping has accelerated because of the increased online shopping activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a survey conducted by the Korea Consumer Agency from May to June 2021, 82% of respondents said they shopped online, which was twice the number found by the same survey conducted two years prior (

B. J. Lee 2021).

5.1.2. Changing Online Market

Online Marketplace

The retail industry in South Korea has evolved into online malls, and accordingly, various forms of online malls have emerged. An overarching trend dominates the South Korean online retail industry, wherein most online commerce is shifting to online marketplaces (

E.-y. Kim 2020). The online marketplace, also described as an online platform, is a digital service that allows interdependence between two or more users and facilitates transactions between users. Thus, suppliers and buyers become customers of an online marketplace, creating a “supplier market”.

Currently, excluding auctions and G-markets, which both started out as online marketplaces in the early 2000s (

Kwon 2012), most online shopping platforms that provide online marketplaces started out with a different business model. Naver, the leading online marketplace, started as a search engine, and other shopping platforms started as either an online shopping site or a social commerce platform. The primary reason for this shift to an online marketplace is to increase product competitiveness by achieving economies of scale (

E.-y. Kim 2020). Here, economies of scale do not equate to traditional supply-side economies of scale. Rather, in an online market context, demand-side economies of scale or network effects are more applicable. The more users use an online marketplace, the more valuable it is to users (

C.-S. Lee 2001). Thus, the network effect allows for stable profit in the online retail market, and achieving it is especially important in an online market environment, as the online marketplace has a significantly lower profit margin than the offline market. Online shopping platforms that are faster to implement in online marketplaces have an advantage in achieving network effects. For example, although SSG.com and Lotte-ON were both launched by traditional retail giants in South Korea, because Lotte-ON implemented the online marketplace faster, it handled more than seven times more products than SSG.com (

E.-y. Kim 2020). Given the current situation of online marketplaces, the strategic position many competitors are taking is to shift towards strengthening logistics (

Oh 2021).

Social Commerce

Social commerce is a combination of e-commerce and social network services (SNS) (

Zhou et al. 2013). As mobile shopping has grown rapidly in South Korea, social commerce usage has grown along with it. According to the status of mobile shopping app usage in the first half of 2013, social commerce users topped the list with 6.6 million users (

S.-h. Ahn 2014b). Social commerce grew rapidly as a curated business model that showed recommended products at the cheapest prices for a specific period of time. First appearing as an online shopping site in 2010 by Ticketmonster (TMON), social commerce later moved to mobile shopping applications and was subsequently considered optimal for the limited screen size of mobile devices (

S.-h. Ahn 2014b). Three prominent social commerce companies dominated the market at that time: TMON, WeMakePrice, and Coupang. However, since 2017, social commerce has lost its original identity and begun to shift to an online marketplace platform. For example, in February 2017, Coupang officially announced that it would switch to an online marketplace-oriented e-commerce company (

Hong 2017). Around the same time, TMON said that it would take the form of a managed marketplace (MMP) that combines the advantages of social commerce and an open market (

Jin 2016).

Naver

Naver was originally South Korea’s largest search engine. Naver started Naver Shopping in 2003 (

Jung and Yoo 2021) and is now the leading online shopping market in South Korea (

A. Lee 2022). Starting out as a search engine, Naver has a unique business model compared to other online marketplaces. Naver allows consumers to search for and pay for a product. It utilizes Naver Pay, a self-owned payment system that offers high membership benefits when subscribed to (

Jang 2021). Naver currently operates two shopping platforms: Naver Smart Store and Shopping Search. As a result, the Fair Trade Commission in South Korea describes Naver as a “platform operator with a ‘double status’ that plays the role of intermediary (shopping search) and is in a position to compete directly with platform entry companies (online marketplace).” (

A. Lee 2022).

5.2. Disruptive Innovation in South Korea’s Retail Industry: Coupang

The South Korean retail industry is constantly evolving. Recently, the industry went through a major shift from an offline to an online marketplace, with online retail sales growing faster than offline retail sales in recent years (

Figure 2). Within this dynamic environment, Coupang became a disruptive innovator. Coupang first started as social commerce in the low-end emerging market. By offering flash sales and lower prices, Coupang engaged in price competition with other social commerce platforms, heavily risking a profit deficit. Due to this risk, Coupang appeared unattractive to existing incumbents, but slowly increased its performance to eventually penetrate the mainstream market.

The direct purchase model was the primary driver of Coupang’s disruptive innovation. Direct purchase is a form of transaction wherein a large-scale distributor mass-purchases products from a supplier, bearing the responsibility for unsold products (

Fair Trade Commission Korea 2022). Coupang was the first to implement such a business model as an online marketplace. Its business practices shifted from providing cheap prices as a social commerce platform to constructing large-scale fulfillment centers (

Dinh 2018). Coupang directly purchased products from suppliers, built its own logistic bases, and controlled its own distribution system. With this business model, the company launched Rocket Delivery as their main differentiation factor (

M.-s. Kim 2021). Starting in 2014, Rocket Delivery was the first to provide fast, one-day delivery of a wide variety of products. This was possible due to its direct purchase model. Coupang was relieved from having to deal with complex affiliate relationships with third-party logistics firms (

Seo et al. 2018). Risking a deficit worth billions of won, Coupang invested heavily in fulfillment and logistics centers to improve Rocket Delivery and overall shipping. Many believed that Coupang’s direct purchase model would ultimately fail due to an increasing deficit; yet, Coupang’s performance only grew. Eventually, Coupang entered the mainstream market by becoming one the top ten e-commerce shopping sites, just three years after the introduction of Rocket Delivery.

At the time when Rocket Delivery was introduced, delivery was not the main focus in the South Korean retail industry. Traditional incumbents did not deem delivery as important either, since they were busy shifting towards e-commerce marketplaces. However, over the course of three years, customers became accustomed to the fast delivery of Coupang. Coupang aggressively invested more in logistics and enlarged the scope of domestic delivery. This led to the launch of faster delivery services from firms that previously only offered regular deliveries, and the industry started to shift focus towards faster logistics, as shown in

Figure 3. As a result, delivery became the key factor in the success of an e-commerce business, with many firms competing to acquire a competitive advantage in logistics, even engaging in cut-throat competition with heavy investments in logistics. Following Coupang, the top e-commerce market leaders all owe their success to their overwhelming logistics infrastructure (

H.-w. Kim 2022).

6. Lotte’s Response to Disruptive Innovation

6.1. CEO Discretion in Lotte

Lotte Group, as a chaebol corporation, relies heavily on its CEO. The decisions and statements of CEO Shin Dong-Bin dictate the direction and future of the firm. This is evidenced by CEO Shin’s interviews and remarks aligning with Lotte’s business decisions, as evidenced by

Figure A1.

First, CEO Shin’s constant push for omnichannel strategies drove Lotte Shopping to strive towards integrating multiple channels into its business. In 2014, CEO Shin recognized the importance of online e-commerce. At the “2014 Lotte Marketing Forum”, he emphasized that Lotte, as an offline retail giant, needed to put more attention on omnichannel strategies to respond to the changing business environment (

S.-h. Ahn 2014a). Accordingly, the following month, the “Omni-channel Promotion Committee” was launched under CEO Shin (

J.-H. Park 2020b). Moreover, Lotte introduced various services that integrated offline and online services. One of them included Lotte’s “Smart Pick” services, which allow customers to pick up online-bought goods at offline stores (

H.-S. Yoon 2016). This service was further strengthened when Lotte introduced the “Pick-up Desk” system, in which customers can receive products directly by visiting the pick-up desk at the Lotte Department store lobby without having to go to the actual store when using the “Smart Pick” service (

Maeil Business 2015).

With this heightened importance on e-commerce, Lotte at first recognized Coupang’s existence in the beginning stages. At the value creation meeting (VCM) in December 2015, CEO Shin mentioned Coupang as a keyword in striving for innovation (

J.-C. Kim 2015). Considering that Coupang was only in its initial stages at the time, introducing Coupang as a benchmarking case for innovation was an unusual move for CEO Shin. He even conducted a case study on Coupang in the same year, further highlighting that Lotte needed to take an open, innovative approach, as seen in Coupang (

J.-C. Kim 2015).

However, as Coupang’s deficit grew, Lotte’s attention to Coupang faded and Lotte no longer acknowledged Coupang as an innovator. Rather, Lotte overlooked Coupang and its threat as a disruptive innovator. This was because despite Coupang garnering attention by creating a new, low-end market with Rocket Delivery at its forefront, its increasing deficit deemed the business model unattractive to traditional retail incumbents. CEO Shin even went on to criticize Coupang’s business model in a March 2020 interview, stating, “Companies with annual deficits of 1 trillion won are not our competitors (

J.-H. Park 2020a)”. This comment reflected CEO Shin’s judgement of being an incumbent, favoring reaping profit from existing businesses. It also revealed Shin’s willingness to enter the e-commerce business with a different approach from Coupang. In fact, in the same year as the interview, CEO Shin emphasized that Lotte needed to take a different direction from Coupang (

Choi 2020). Instead of adopting and following Coupang to focus on investing in fulfillment and logistics, Shin suggested a new type of innovation that would integrate Lotte’s various businesses into one platform. Extending his emphasis on omnichannel strategies, this was the introduction of CEO Shin’s ambitious footsteps towards the e-commerce industry.

Lotte-ON was introduced in April 2020 as an ambitious attempt to differentiate itself in the changing environment of the South Korean retail industry (

Beom 2020). This was Lotte’s alternative option to Coupang. Lotte-ON aimed to become an “integrated e-commerce shopping platform”, bringing together Lotte’s scattered business units into one e-commerce shopping platform (

Beom 2020). Lotte-ON also had a new strategy to introduce a “hyper-personalized and mass customized service”. The service promised to provide recommendations based on analyzing shopping behaviors of the 39 million existing Lotte members, who accounted for 75% of the entire South Korean population (

Han 2019). Under this initiative, the promise was to provide a “customer-centric shopping platform”, a concept similar to Netflix’s recommendation system (

Y.-s. Park 2020). Lotte-ON’s endeavors of creating differentiation aligned with CEO Shin’s approach in not following Coupang’s footsteps. Again, rather than strengthening logistics, Lotte-ON focused on personalization. Even in 2021, CEO Shin repeatedly stated that Lotte-ON would take a different approach from Coupang, as he emphasized to Lotte’s board members with the comment, “We have to take a different route from Coupang.” (

Moon 2021).

6.2. Lotte-ON’s Performance

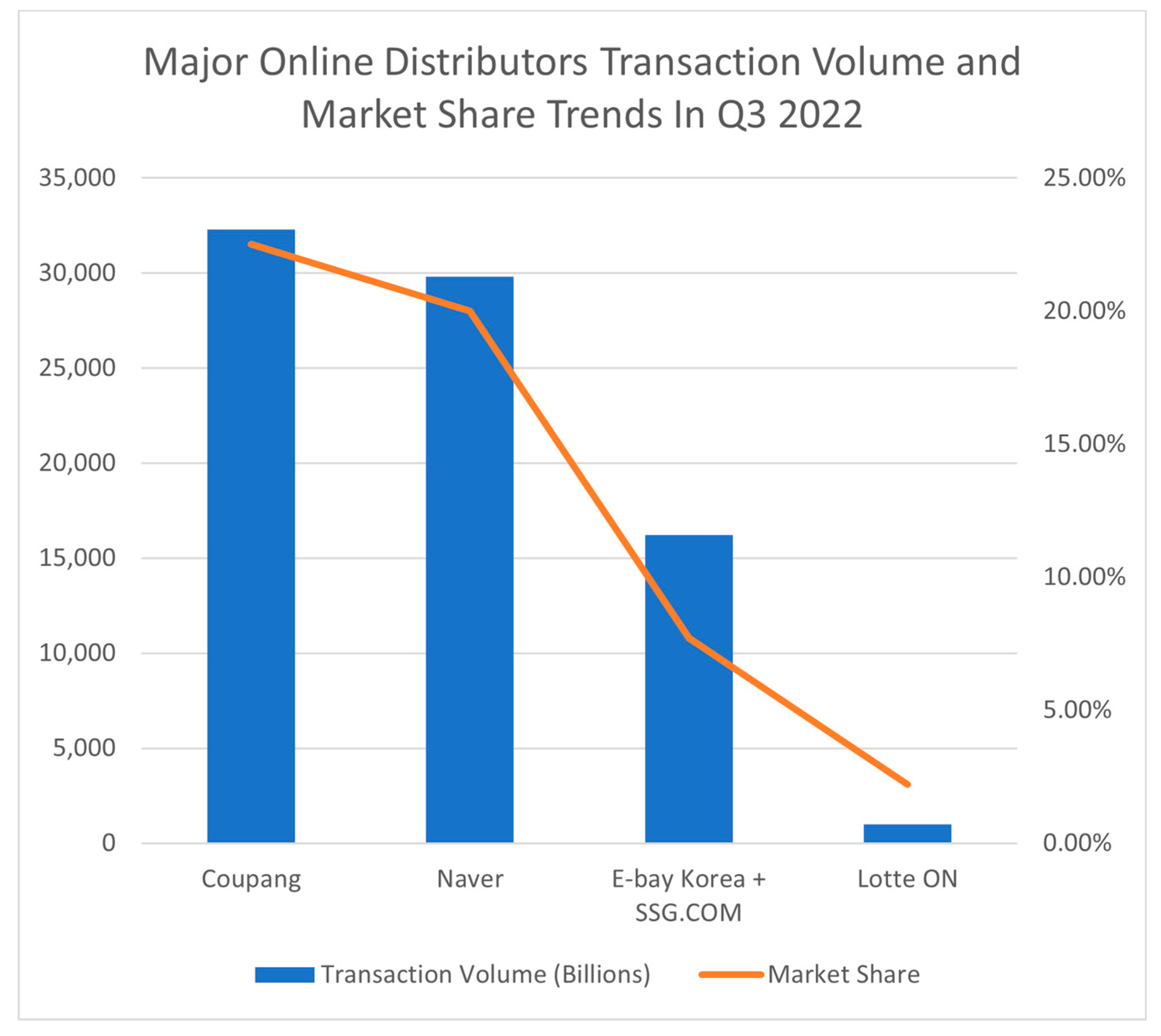

Lotte-ON initially had high expectations for success. Lotte was, in fact, an established retail giant possessing advantageous resources and core competencies in the retail market. With numerous offline stores and a large customer base, Lotte-ON claimed to be the next-generation e-commerce giant. However, Lotte-ON showed lackluster performance, even after the growth of the e-commerce sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lotte-ON’s total transaction volume growth rate reached just 18.1% in 2021, while Coupang showed 72% growth. Other competitors, including Naver Shopping and SSG, showed 40% and 22% growth, respectively. Moreover, although the number of monthly active users (MAU) and third-party sellers increased, the number of buyers still decreased from 1.6 million at the end of 2021 to 1.4 million in March 2022 (

Lotte Shopping 2022a). The gap only increased in 2022. As shown in

Figure 4, while Coupang’s total transaction volume reached more than KRW 30 trillion, Lotte-ON reached less than KRW 5000 billion.

In addition to Lotte-ON’s performance, the platform also faced many difficulties. First, Lotte-ON was subjected to multiple errors and crashes from its launch day. Lotte was originally scheduled to launch Lotte-ON at 10 a.m. on the 28th of April; yet, it was not able to open at the notified time owing to delays in server relocation (

D.-e. Park 2020). Lotte-ON also came under criticism for poor customer service. Many customers made complaints, stating that the platform was purposefully avoiding communication with customers (

Na 2020). Most importantly, the platform encountered multiple challenges when integrating its business units under one platform. Since business practices in each unit were conducted differently, even simple tasks such as unifying product codes were a challenge. Lotte-ON had to spend months unifying products under a single code. There was also a problem with recording sales under the Lotte-ON platform (

D.-h. Park 2021). Moreover, Lotte-ON did not integrate all business units of Lotte Shopping. Affiliates such as Lotte Hi-Mart—an electronics retail mall—and Lotte Home Shopping still operated separate online shopping sites, even when Lotte-ON was advertised as a one-stop integrated shopping platform for all Lotte Shopping (

Jeong 2022). All these incompetencies created confusion for both existing Lotte employees and customers.

6.3. Reasons for Lotte-ON’s Slow Performance

Despite Lotte-ON being CEO Shin’s ambitious attempt, the platform demonstrated slow growth and low market share, especially compared to Coupang. Not only did it fail to properly utilize Lotte’s existing resources, but there was also no synergy between the integration of existing business units and the new platform. This poor performance of Lotte-ON can be explained in two ways.

First, Lotte-ON was a latecomer to the e-commerce platform market. The platform was launched in April 2020, long after competitors had already established a strong presence in the market. For one, Coupang had already established itself as the market leader by strengthening its Rocket Delivery service (

Figure 5). It was apparent that Lotte neglected to respond to disruptive innovation in the South Korean retail industry at the right time.

According to

Caillaud and Jullien (

2001), in a market with fierce price competition and well-established market leadership, new entrants are highly discouraged because of high entry barriers. This is because the best-established market leader, the winner, takes most of the customers. Further, when network effect is combined with disruptive innovation, the market becomes even more impenetrable (

Caillaud and Jullien 2001). Coupang, as the new market leader, shifted its industry standard to fast delivery time of Rocket Delivery. In this sense, Lotte-ON had limitations in creating a competitive advantage from its launch. However, instead of responding to Coupang’s faster delivery services, Lotte-ON tried to implement a hybrid integration solution following CEO Shin’s remarks on Coupang and omnichannel strategies. Yet, Coupang failed to acknowledge that customers had become accustomed to fast delivery systems. Following Coupang’s success with Rocket Delivery, competitors responded to the success by implementing Coupang’s fast delivery, as shown in

Figure 3. With this, fast delivery became a standard for customers, even proclaiming a new “age of quick shipping” (

H. Lee 2022). Thus, not recognizing Coupang as a disruptive innovation at the right time became a detrimental factor that was influential to Lotte-ON’s lackluster performance.

There was a reason for CEO Shin overlooking Coupang as a disruptive innovator. Disruptive innovation does not start with a noticeably large performance. Instead, it deals with the process of a smaller company encroaching on some of the market share by prioritizing lower price, not performance. Over time, the inferior company eventually beats market-dominating incumbents (

J. H. Lee 2018). Likewise, Coupang started at the low-end, emerging market, swallowing a large sum of deficit in its initial stages. This was enough for Coupang to avoid being noticed as a threat to incumbents. Most incumbents, including CEO Shin of Lotte, deemed Coupang’s deficit model as unsustainable. However, its performance grew over the years, eventually overthrowing the existing market leadership. This left CEO Shin no choice but to not respond to the new threat.

Another aspect to consider is the passive response of Lotte-ON. For Lotte to not lose its position in the retail market, new breakthroughs were needed. Yet, following CEO Shin’s approach on taking a different route from Coupang’s deficit business model, Lotte-ON decided to take a conservative investment approach. In 2020, Lotte-ON declared that it would not conduct business that risks a deficit and would not participate in destructive, cutthroat competition with its competitors (

J. Shin 2020). Following this statement, Lotte-ON adopted a low-risk, passive strategy. This was the direct opposite of Coupang, which was infamous for its aggressive investment strategy in logistics. However, SSG, another retail incumbent, made heavy investments in response to Coupang. With efforts in forming joint ventures with Naver, acquiring eBay Korea, and constructing logistics centers (NEO003), SSG showed focused endeavors to grow its logistics bases and strengthen last-mile services (

S.-h. Ahn 2019). Compared to this intense competition in the South Korean e-commerce market, Lotte-ON pursued a passive strategy, leading to the firm’s lackluster performance.

6.4. Lotte’s Late Response to Disruptive Innovation

The exact point at which CEO Shin recognized Coupang as a form of disruptive innovation is unclear. However, as Coupang improved its performance and became market leader, it was clear that Coupang was a new threat to existing retail incumbents. In January 2021, CEO Shin, reflecting on the sorry performance of Lotte Shopping and Lotte-ON, stated, “The reason for slow business, despite being the first in the industry, is due to implementation, not the strategy itself.” (

J.-Y. Kim 2021). Though this statement is not a confirmation of CEO Shin’s recognition of Coupang, it reveals his recognition of the weak implementation of Lotte-ON.

Lotte-ON’s actions further reveal that CEO Shin was conscious of Coupang’s disruptive innovations. In July 2020, the dawn delivery service “ON at dawn” was launched under the Lotte-ON platform. The “ON at dawn” service enabled fast delivery of fresh produce and side dishes from Lotte Mart. When customers ordered the products by 9 p.m. the day before, the delivery was made early the next morning (

Han 2020). However, even with the launch of such a service, it was not enough to garner Lotte-ON success. Logistics competition was already dominated by existing players, most prominently by the disruptive innovator Coupang. As mentioned above, competitors had already made heavy investments in fulfilment centers to achieve faster delivery. Lotte-ON soon recognized the limitation, as it withdrew from all dawn delivery services in April 2022. It also withdrew from other fast delivery services, including the “right-away delivery service,” (

J.-y. Lee 2022).

However, Lotte made a surprising decision to invest KRW 1 trillion in Ocado in November 2022 (

Jung 2022). Ocado is a retail technology firm and a leader in online grocery delivery solutions. Ocado utilizes the Ocado Smart Platform (OSP) as a key feature for forecasting inventory management based on data and artificial intelligence (AI) (

Jung 2022). This lowers the disposal rate, which is the biggest disadvantage of online food delivery. Moreover, at Ocado’s Automated Logistics Center (CFC), robots freely move around grid-shaped rails that store products and pick and pack products, storing more than 45,000 items (

Jung 2022).

Thus, Ocado is a strict logistics-focused firm that provides solutions to other global distributors. By concluding a partnership with Ocado, Lotte plans to build six Central Fulfillment Centers (CFCs) and use Ocado Smart Platforms (OSPs) to improve Lotte’s existing fulfillment systems (

S.-k. Yoon 2022). Moreover, in the partnership, Lotte plans to integrate its existing logistics systems from markets and supermarkets (

S.-k. Yoon 2022). With this, Lotte further plans to increase omnichannel synergy by strengthening its logistics and inventory management efficiency. This deal reveals that Lotte shifted its focus from personalized services to logistics, indirectly revealing Lotte’s recognition and response to Coupang.

6.5. Analyzing Lotte’s Response

With the growing threat of disruptive innovation, Lotte essentially has two options: (1) continue to focus on its existing core business or (2) accept disruptive innovation and adapt to the change (

Markides 2006).

Lotte could have accepted disruptive innovation and created new organizations to adapt to the changes. When creating a new organization, Lotte had two choices: to create within the firm or to separate entirely from its existing business. This is determined by the perceived threat of disruptive innovation, organizational capabilities, and how core competencies are utilized. SSG is an example of such an approach. Shinsegae Group, as a direct competitor of Lotte in the traditional offline retail market, noticed Coupang’s threat and responded by adopting disruptive innovation in 2019 (

Samil PWC Accountings 2021). After a careful analysis of its existing core business and resources, the Shinsegae Group created a separate, independent company, SSG.com, by combining Shinsegae and E-Mart’s existing online e-commerce departments and investing in logistics to respond to Coupang’s Rocket Delivery (

S.-y. Ahn 2019).

Lotte followed the opposite approach. Lotte, as an incumbent in the South Korean retail market, already possessed strong core competencies within its existing resources. Lotte not only had the largest offline distribution channel, but also gained brand recognition in the nation. Utilizing this core competency, Lotte’s first option was to continue building on its existing resources. According to Osiyevskyy and Dewald, incumbents choose to exploit using two methods: (1) to resist innovation, aggressively protecting and defending original business routines, and (2) to strengthen existing routines without adapting to change (

Osiyevskyy and Dewald 2015).

Lotte, at the forefront, followed the first option of continuing to focus on its core business. With the launch of Lotte-ON, Lotte attempted to strengthen its existing Lotte affiliates without adopting this change. Yet, as explained above, this implementation did not bring any synergy to Lotte and only resulted in lackluster performance. Therefore, Lotte took a loss in both accepting disruptive innovation and strengthening its core business. This led Lotte to accept a rather ambivalent approach, taking only conservative steps. Even after recognizing Coupang as a disruptive innovator, its implementation of faster delivery systems was weak and only brought minor developments.

Keeping on with the ambivalent approach, the next move for Lotte, for a moment, shifted to external partnerships. This was evidenced by Lotte’s merger and acquisition (M&A) with the furniture platform Hanssem and the used goods service platform JoongoNara in 2021 (

H.-s. Park 2021). However, this did not contribute to the development of Lotte-ON’s market share. Reflecting on Lotte’s actions, it was not until very recently that CEO Shin fully realized Coupang as a disruptive innovator, which shifted the entire industry’s focus to logistics.

7. Discussions and Conclusions

This study explores factors that can influence the response of a traditional firm in the context of the South Korean retail industry. In particular, the research entailed a case study on Lotte to reveal that the factor most strongly influencing incumbent responses was CEO attention. By aligning Lotte’s performance and actions with CEO Shin Dong-bin’s previous interviews and statements regarding the management of Lotte Shopping in chronological order, this study confirms that Lotte indeed values CEO discretion as a key determinant when making decisions, including the response to disruptive innovation. As seen in the case of Lotte-ON, CEO Shin’s focus determined the overall actions of the firm—in this case, the late and inappropriate response to disruptive innovation in the industry. This study emphasizes the importance of managerial perspectives and suggests the need for further research on the relationship between managers’ attention and innovation.

Moreover, this study is meaningful to the extent that the theory of disruptive innovation was applied to a real-life business case to specifically explore the behavior of an incumbent when responding to the threats of new disruptive innovation. This extends and complements prior studies on disruptive innovation. Furthermore, unlike previous studies that examined incumbent responses to disruptive innovation simply to apply the theory to a real-life phenomenon, this study dives further into the analysis and emphasizes the additional importance of the manager’s perspective. The need for further research on the relationship between managerial leadership and disruptive innovation is emphasized throughout the paper.

Variations exist in incumbent responses. We have shown several case examples for future investigations to follow and further allow for the development of a more nuanced view on the factors leading to incumbent firms’ responses to disruptive innovation. Further research on this issue can shed more light on CEO attention and how managerial decisions lead to specific firm’s actions, specifically concerning responses to disruptive innovation. Such studies can not only enrich incumbent responses to disruptive innovation but study the management of innovation as well. Our findings also have implications for incumbent firms. As the study emphasizes the significance of CEO attention and leadership, managers need to pay special attention to dealing with innovation. When dealing with disruptive innovation, incumbent managers must adapt to the mindset of an innovator to recognize, but most importantly, develop a timely and strong response to disruptive innovation.

There are still some key limitations in this study. First, a key limitation stems from the lack of primary sources used in the study. Although this paper relied on various sources of secondary data to increase reliability, there existed an inherent lack of control over the data collection process data, which may lack contextual information that could influence the interpretation of the findings. Moreover, as data collection was performed with a specific research objective in mind, the possibility of researcher bias was introduced in the process. Hence, future research opportunities include systematic data validation to empirically test the findings of this study. Second, because this study used qualitative analysis, the research was only conducted with empirical evidence stemming from anecdotal resources. Therefore, specific numerical comparisons and the range of analysis time were fundamentally limiting factors in the study. Third, as this study focused on CEO attention as a key factor influencing the incumbent Lotte’s response to disruptive innovation, it overlooked the analysis of other factors that may have also influenced Lotte’s decisions. This study only focused on the retail environment of South Korea, and only analyzed Lotte in terms of Lotte Shopping and e-commerce, overlooking other subsidiaries of the Lotte Group. Since CEO Shin manages across the Lotte Group, his decisions on Lotte Shopping following a conservative approach toward disruptive innovation could have been a strategic move to focus on other priorities in diversifying the overall portfolio of the Lotte Group. Fourth, the special governance structure of chaebols may be a country-specific factor in South Korea. Thus, further studies on the relationship between CEO attention and incumbent responses to disruptive innovation should be conducted in different corporate management structures in different countries. Finally, continued observations of the partnership between Lotte and Ocado are needed in the future, as the partnership is still in its early stages without any specific plans or business portfolios.