Abstract

Japanese firms have historically followed a country-specific model of corporate governance. Yet, Japan has had to adapt its corporate model over the last 30 years, along with the transformation of distinctive characteristics of Japanese capitalism in the same period. We review the historical evolution of Japanese corporate governance over the last three decades with a specific emphasis on the changes in the capital structure of major companies and the efforts to correct ineffective board of directors monitoring. By doing this, we investigate to what extent specific Japanese corporate governance features may explain the nation’s economic situation over this period. Thereby, we try to clarify the influences that have presided over recent corporate governance reforms in Japan despite the existence of managerial failures and corporate scandals. This paper places itself into the debate over the diversity of capitalism as it portrays the specificities, differences, and converging trends of Japanese corporate governance practices.

1. Introduction

Comparative corporate governance was initiated in the 90s with works stressing the key role of law and legal applications on a firm’s governance, market expansion and economic progress (Aguilera and Haxhi 2019). These studies provide the tools to categorize institutional frameworks and analyze their impact on firms’ financing, stakeholder relationships and economic behavior. Academic and policy discussions emerged as to whether or not an increasing globalization of economies made it necessary for the different methods of controlling and structuring corporations to become compatible, at least in order to have the corporation open to foreign investors. Despite those convergence forces, alternative models of corporate governance are still observable, especially in Europe and Asia, and have been theoretically debated in the comparative institutional analysis setting (Aoki 2001) and the regulation school (Boyer et al. 2012).

Most continental European economies have adopted a way of corporate governance known as the stakeholder model (Burger-Helmchen and Siegel 2020). The concept of stakeholder covers the individuals and constituencies of a corporation that contribute, either voluntarily or involuntarily, to its wealth-creating capacity and activities and that are, therefore, its potential beneficiaries and/or risk-bearers. The stakeholder view emphasizes long-term strategies, stable capital with blocks of shareholders and protection of not only shareholders but the broader category of stakeholders: debt holders, managers, employees, customers, governments, etc. (Feils et al. 2018). Nevertheless, within European nations, a variation of corporate governance regimes exists. On one side, Northern European countries are said to have a system of concentrated ownership and more cooperative relations with employees. On the other side, Latin countries (like France, Italy, and Spain) adopted a mixed economy, with concentrated ownership but more conflictual relations between employers and employees (Cernat 2004).

In Asia, corporate governance research gained ground in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, which was partly attributed to the weak level of corporate governance in the region. This crisis indicated that good corporate governance matters not only for individual corporations but for the whole economy to benefit from stable economic conditions. Keeping in mind that Asia is a region of various development levels and institutional frameworks, the common feature that has emerged is the prevalence of family ownership and relationship-based transactions (Songini and Gnan 2015). This implies that firms are run with a long-term vision in mind, which can be positive for the stability of the economy. Moreover, controlling families have more incentive to closely monitor firms’ actions and decisions. But if the company gets entrenched with poor management, a dual-class stock structure can make it hard for shareholders to dislodge it and hinder activist investors. The concentration of ownership in Asia is often explained as a consequence of weak legal and institutional environments and a high level of corruption in developing economies (Dinh and Calabrò 2019). The Asian system is often referred to as “insiders-centered,” meaning that a corporation is part of a broader network of stakeholders holding very long-term relations. Despite these commonalities, there is a variety of ownership structures within Asia related to different forms of control depending partly on the culture of each country (Le Corre and Burger-Helmchen 2021a, 2021b).

In this work, we examine the experience of Japan, which has had to adapt its corporate model over the past 30 years in response to the transformation of distinctive characteristics of Japanese capitalism during the same period. The landscape of Japanese capitalism and corporate culture in the early 2020s differs significantly from the initial descriptions that arose from comparative studies in the 1970s, the excesses of the 1980s bubble, and the so-called “lost decade” (1992–2004), which raised questions about the Japanese model. The financial regime under which the Japanese economy is operating has been completely transformed, global corporate structures standards have gained momentum, lifetime employment has been eroded and is only still applicable to a minority of well-trained employees, and yet Japanese capitalism has not converged into a subset of Western or American capitalism. Indeed, Boyer (2014) argues that Japanese capitalism is the result of a hybridization between some components of American capitalism and the institutional constraints inherited from the period of reconstruction between the 1950s and 1970s.

The early 1990s marked a peak in the study of the virtues of post-war Japanese economic firms, but there were also analyses highlighting the fact that the system was in need of change (Aoki and Dore 1994). Since the collapse of the so-called Bubble economy in the early 1990s, Japanese firms have been subject to fundamental pressures to change core elements of their institutional setting, such as the main bank system, stable cross-shareholding, board controlled by insiders and lifetime employment. Indeed, in the 1990s, corporate governance reforms emerged as a serious issue in Japan as the country underwent substantial changes leading to growing diversity in the situations of major companies. This discussion on the changing corporate governance practices can be seen within the broader intellectual inquiry regarding the extent to which the Japanese economy has converged towards American-style finance-led capitalism. A significant contribution in this regard has been made by Masahiko Aoki, who has played a crucial role in understanding the decision-making structure and information treatment within traditional Japanese corporations known as J-Firms (Aoki 1988). Aoki’s comparative institutional analysis of Japanese firms (Aoki 2001) shed light on the diversity of corporate governance practices among Japanese firms, as documented by Aoki et al. (2007). Aoki et al. (2007) argued that Japanese corporate governance has become more diverse since the constraints of the main bank systems have diminished, allowing for alternative forms of organization in terms of business strategy, structure, management, and employment patterns. However, as noted by Aoki et al. (2007, p. 428), “the old rules of the game can no longer be taken for granted, but new rules are still being sought and are in the process of evolving.” Similarly, Lechevalier (2014) calls for a new research program on Japanese capitalism that acknowledges the diversity of different types of capitalism. It is crucial to assess the position of the Japanese model and how it responds to the questions and tensions posed by other forms of capitalism.

Building upon this line of reasoning, the primary objective of this paper is to comprehensively examine the recent transformations in corporate Japan prompted by the neoliberal movement, internal dynamics, and the evolving nature of Japanese capitalism over the past two decades. This paper will first present notable facts about corporate governance in Japan, highlighting its unique characteristics and the challenges it faced during the two lost decades. Subsequently, we will delve into the influential factors that have shaped recent corporate governance reforms in Japan. Finally, we will conclude with a discussion that underscores the potential implications of these governance evolutions and highlights avenues for future research.

To achieve this objective, we have employed a narrative literature review methodology (Allen 2022; Guimtrandy and Burger-Helmchen 2022), wherein we have collected and analyzed highly cited and widely recognized sources on Japanese governance. Through this process, we aim to derive meaningful insights and provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

2. Governance, Economic Inefficiencies and Corporate Scandals

2.1. Corporate Governance in Japan, a Primer

The focus of this paper is contemporary corporate governance evolution in Japan, but in an attempt to escape the narrow circle of Japanese corporate governance specialists, we intend in this section to introduce some historical elements and key concepts that would help the reader to better understand some path-dependencies and evidence of hysteresis in the development of the Japanese corporate culture. Historically, traditional business conglomerates, known as zaibatsu, have played a significant role in the rapid economic growth of Japan, extending roughly from 1955 to 1980 (Nakamura 2015). The zaibatsu (literally translated into financial clique) form of doing business emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. Usually, a family would own all the shares of a main holding company (Honsha) that itself controlled and had stakes in a network of industries, financial institutions and diverse subsidiaries. This is known as cross-shareholding. The corporate culture in the network was such that employees felt a strong personal devotion to the owning family (Hoshi and Kashyap 2001). The first four families to embody this culture were the Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Yasuda. Then came, in the 1930s, the Toyoda, Suzuki, Iwai and Nomura families. After World War II, the biggest zaibatsu were dissolved, and their holding companies were banned by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers as they had actively taken part in the war effort and colonial activities. This legislation was kept in effect until 1952 when the use of old zaibatsu names and logos was again allowed. They were superseded by the keiretsu after the war, a new form of conglomerate with, at its center, a main bank that played the role of a coordinator and last-resort financer. The keiretsu structure is characterized by “stable shareholders” with reciprocally held cross-shareholdings among corporations and banks. These ownership ties often overlap with and underwrite various other cooperative business relationships within corporate groups. The keiretsu played an important role in coordinating the industrial strategies of the members of the conglomerate during the high-growth period of the Japanese economy (1950s to 1980s). Yet, the power of coordination of the keiretsu has been in decline since the 1990s (Lechevalier 2014). Moreover, the 1980s were marked by a wave of corporate privatization, notoriously in transport (Japan National Railways) and telecommunication industries (Nippon Telegraph, Telephone Public Corporation). This had the effect of further accelerating the adoption of modern company frameworks in Japanese firms and promoting the rise of professional managers (Carney et al. 2018).

According to Hoshi and Kashyap (2001), before the military build-up of the 1930s, Japan’s corporate governance was essentially led by shareholders, and boards of directors were yet to be influenced by bank representatives. Yet in the early post-war period, “lifetime employment,” a norm for regular in large companies, became institutionalized in tandem with the emergence of cooperative enterprise-based unions (Gordon 1998). In concomitance with the rise of professional managers who came to executive positions, the situation shifted. Indeed, lifetime employment in Japan made for a strong corporate culture and loyalty from employees that would have their whole careers within the same company. Because of the cross-shareholding culture, Japanese boards of directors are mainly composed of insider directors that also hold top management posts. Traditionally, the Japanese corporate governance model is characterized by a stakeholder-oriented system with a weak market for corporate control, as cross-shareholding practices favor stable shareholding. Management and employees are at the center of the Japanese corporate governance. However, recently, the Japanese model has seen reforms toward a more shareholder-oriented form of capitalism that may alter the way Japanese firms act and perform, as we will see in the next sections.

2.2. Corporate Governance Inadequacies and the First “Lost Decade” (1990–2000)

This section will provide an analysis of the ongoing divergence of corporate governance in Japan from international standards and its potential impact on the country’s economic underperformance since the 1990s. As aptly stated by Kato et al. (2017, p. 486), “the Japanese economy has persistently performed poorly over the last two decades, with one of the alleged culprits being Japan’s unconventional and, some argue, ineffective corporate governance.” In their study, Kato et al. (2017) highlight two key aspects of Japanese corporate governance that are perceived as inadequate when compared to international standards. First, they emphasize the role of banks, which not only provide loans but also frequently hold significant blocks of shares, occupy board seats, and tend to align closely with management. Second, they shed light on the prevalence of corporate share cross-holdings, particularly among companies within the same group. The tightly held nature of these shares has posed substantial obstacles to mechanisms that facilitate change, such as hostile takeovers or shareholder activism, thereby solidifying the position of Japanese managers. These characteristics have created significant challenges, limiting the effectiveness of external pressures to drive transformative actions within Japanese corporations.

This has been notably exemplified by Schembera et al.’s (2023) approach to local governance and sensemaking. They emphasize that certain governance arrangements, which may diverge from external regulations or activities, facilitate local sensemaking and thereby facilitate corporate governance for specific activities.

We will first analyze the impact of ownership structure and the importance of governance imposed by banks. Then we will take a look at the insufficiencies of board monitoring in Japanese firms. A final sub-section will discuss the overall ranking of Japanese firms on the Governance Index at the end of the first lost decade.

2.2.1. Capital Structure of Japanese Firms and Non-Performing Loan

The key factor of corporate governance in Japan has long been banks and financial institutions. Indeed, in order to catch up with developed and modern countries, the model of Japanese capital structure has been based on an accumulation of capital through a solid banking system. For Hoshi and Kashyap (2001), the bank-dominated system truly emerged after 1945. This is a product of the economic war effort undertaken by banks when the securities market was shut down by the military government. At this time, loan evaluation and monitoring were not subjects of concern. This situation of few controls went on after the war and was kept intact by the Occupation forces to assure financing capacities in a capital-starved economy (Miwa and Ramseyer 2002; Morck and Nakamura 1999). Moreover, despite zaibatsu being dissolved after the Second World War, corporate groups remained a key part of Japanese business. Kigyo shudan (horizontally diversified groups) and keiretsu consisted of groups of companies linked by close financial relationships. Usually, and similar to the former zaibatsu system, a Japanese main bank is at the center of a network that links companies by cross-shareholding. Up until the 1980s, the equity market in Japan was weak as the equity capital ratio of manufacturers never topped more than 30 percent (Okumura 2004). Therefore, banks were urged to hold equity shares in Japanese firms so as to keep capital injection at high levels. Banks and financial institutions were incentivized through an unprecedented easy monetary policy. Additionally, it could be argued that one of the main reasons for the banks to make the equity investment in their clients was not to enhance their capital adequacy but to gain a good relationship with those corporate clients, which were eager to find “stable and quiet” shareholders. Banks competed with each other’s to increase lending at that time, which was one of the major reasons that created the condition for a financial bubble. As explained by Okumura (2004), investment risks were protected by a book-value accounting system by which banks could bear a hidden reserve resulting from a positive trend in the increase of stock prices. This system was successful as it was backed by powerful state interventions. This procedure is opposite to the regulatory state that avoids intervention in the private field. In this sense, some researchers often draw a parallel between Japan’s economy and the Coordinated Market Economies like Germany, the Netherlands or Sweden. In the 1980s, the Japanese economy was at its best, with capital supply exceeding demand and the development of an affluent Japanese society enjoying accessible consumer goods. But this excess of capital sponsored by the Bank of Japan, which even reinforced its easy monetary policies, led to less discipline in its allocation. New financial technologies and credit expansion at a fast pace led to negligent lending standards and created a friendly environment for a financial bubble that burst in the early 1990s. Okumura (2004) argues that the lack of supervision by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and the silence of minority shareholders out of fear of losing business relationships with banks were some of the reasons for this crisis. Fukao (2003) backs this reasoning by blaming the lost decade on the weak governance of Japanese banks and insurance companies. Finally, Morck et al. (2001) argue that Japanese corporate governance helps explain the poor economic performance of its corporate sector during this period.

2.2.2. Ineffective Board of Directors Monitoring

An independent board of directors to oversee management and represent the interests of shareholders is widely recognized as a central point of good corporate governance (Krause et al. 2017). Its prime tasks are to hire and replace the CEO, oversee performance, evaluate corporate strategy, and judge financial reporting and risk management. In a common firm, most of this effort is done through board meetings and specific board committees. A hierarchical structure is central in Japanese bureaucratic established firms. Top executives represent the elders of the community, and they are primarily concerned with the reputation of the community more than its performance (Dore 1998, 2005). The internal promotion system is highly elaborate and is more designed to preserve job security than to promote new or external talents. Indeed, large manufacturers and, in general, traditional Japanese firms reward loyalty to the community with lifetime employment within the company to employees with core competencies. Therefore, corporate managers tend to have long careers in firms in which they control the day-to-day operations. Top management in the Japanese public company is organized and supervised by a board of directors and a board of auditors, both appointed by shareholders. The board of directors selects the representative director (daihyo torishimari yaku)—in many cases, the president is designated as a representative director, but the chairperson is not necessarily designated as a representative director—that represents the firm and manages the business. Ballon and Tomita (1989) have shown that around 45% of Japanese firms had no independent directors. Hence the criticism around Japanese boards of directors not fulfilling their monitoring and controlling functions. Kato and Kubo (2006) indeed describe the annual shareholder meeting of Japanese companies as being a mere formality. Moreover, the president’s decisions are usually influenced by a board of senior managing directors (jomukai) and are never confronted with complaints unless business performance declines.

2.2.3. Japanese Corporate Governance Performance vs. the Rest of the World

Is Japanese traditional corporate governance fundamentally less efficient than Western-like governance? Researchers have long tried to prove a global causality effect between corporate governance and Japanese corporate performance (Bauer et al. 2008; Hirota et al. 2010; Luo and Hachiya 2005). This research shows solid relations between aspects of corporate governance practices (independent board of directors, executive compensation, audit committee, etc.) and economic performance. Based on those results, governance indexes can be created reflecting a firm’s global corporate governance and its effect on its performance. It has been done among others in Europe (Bauer et al. 2004), France (Hamza and Mselmi 2017), the United States, and Canada (Bozec and Bozec 2012). Governance Metrics International (GMI) offers a global governance index (GOV) based on more than 500 corporate governance features categorized into six governance indices: board accountability, financial disclosure and internal controls, shareholder’s rights, remuneration, market control, and corporate behavior (El-Helaly et al. 2018; Vig and Datta 2018). Japan ranked second to last when its corporate governance is measured relatively from international standards. When divided into sectors of activity, it is interesting to note that Japanese banks have the lowest governance rating. Using stock price as a criterion, on average El-Helaly et al. (2018) found that Japanese firms with a high rating significantly outperform Japanese firms with a low rating by up to 15.12% a year.

To resume this section, a lack of external board oversight, prevalent cross-shareholding and insufficient disclosure were some of the explaining factors for the two lost economic decades from the 1990s to 2010. Japan has been plagued by over-investment, excessive conglomeration and over-indebtedness. These tendencies have been, to a large extent, a result of poor corporate governance (Aronson and Kim 2019). In the next part, we will determine to what extent those flaws in Japanese corporate governance can explain the wave of corporate fraud and scandals Japan saw during the 2010s.

2.3. Governance and Corporate Scandals during the 2010s

During the 1970 and 1980s, Japanese corporations were looked upon worldwide for their manufacturing efficiency, their models of business strategy and innovation capabilities (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). New management techniques such as kaizen, target costing and flexible production influenced the global economy. But recently, the country has known a wave of corporate scandals that tarnish its legacy. This phenomenon is usually linked directly to what we have explored in the preceding section. Corporate scandals in Japan can indeed be explained by two main factors, a slumping economic environment and an idiosyncratic Japanese corporate culture.

2.3.1. Japanese Corporate Culture

Japanese corporate culture is characterized by a strong hierarchical structure and an emphasis on putting the harmony of the company above individual opinions (Kimura and Nishikawa 2018). Moreover, as in the broader Japanese society, the shame of losing face and admitting failures is particularly strong. Dutta and Lawson (2018) explain that this can mean having executives do everything they can to achieve or exceed their goals regardless of the economic setback Japan’s economy was facing. The authors claim that “While the CEOs didn’t necessarily instruct their subordinates to commit fraud, they created an environment conducive to fraud and relied on the Japanese culture of obedience and loyalty that led employees to do whatever was necessary to meet these targets, including fraud” (Dutta and Lawson 2018, p. 42). This environment is further emphasized by the long-term orientation that embodies Japanese companies. Lifetime employment schemes for core employees inevitably builds a strong sense of camaraderie within the workplace and thus does not give much space for individual to challenge inappropriate corporate behaviour.

2.3.2. The Olympus and Toshiba Cases

One of the most notorious recent corporate scandals was the Olympus case that broke in 2011 and revealed that a total of $1.7bn worth of losses had been hidden by the company management for over two decades. The fraud at Olympus is directly linked to the changing economic environment of the late 1980s. The camera manufacturer was heavily reliant on the exportation of its products to global markets. But the appreciation of the yen in the mid-1980s reduced its sales income. To compensate for this loss, Olympus started to participate in speculative investments, which at the time were highly profitable given the steep rise of asset prices. After the burst of the asset bubble, Olympus tried avoiding losses on its portfolio by investing in significantly riskier financial instruments but failed dramatically. According to a thorough investigatory report led by independent lawyers, the fraudulent financial reporting was part of the vortex of frantic efforts into which many companies were drawn when the bubble economy reached its peak (Olympus Corporation 2011). However, despite a high turnover of executives, all the CEO resisted disclosing the losses, which at the end of the 1990s, topped 100 billion yen. They did so in compliance with the Japanese Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) until it was harmonized with the US GAAP in April 2001. It is especially required for companies to disclose the value of their investment with a mark-to-market methodology that records, on a day-to-day basis, the value of an asset according to its market price. Through a complex scheme of shell companies organized by the CEO, CFO, Chairman of the board, and some executive vice presidents, the losses were meant to be diluted and hidden from Olympus’ financial reports. Eventually, soon after a newly appointed British CEO (Michael Woodford) tried to ring the alarm on the situation, the board of directors fired him. Eventually, the Tokyo District Court found Olympus guilty of the violation of both the Securities and Exchange Act and the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act for fraudulent financial reporting. In April 2012, in a special Annual General Meeting (AGM), the shareholders appointed a new management team while the old team resigned. For many observers, this case managed to show how some Japanese corporations are still mired in a strong inward mentality, meaning that top managers could sacrifice personal principles and creeds in order to protect the corporate name. As reported by Shoji (2018), no one seemed to be interested in getting rich themselves; they just wanted to preserve the honor of the company name. Furthermore, no one questioned that motive or debated whether it was right or wrong. Indeed, the three top corporate managers arrested on suspicion of falsifying financial reports never stole money from the company. To Tetsuhiro (2013), who studied the tacit power of established firms in Japan, “the ultimate purpose of their wrongdoings was apparently not the pursuit of personal profits, but the protection of their company and the management team to which they belonged” (p. 423).

As in the Olympus case, the fraud at Toshiba similarly started in the aftermath of a crisis, this time the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, and lasted for seven years. The major Japanese technology company manipulated its earnings in two sectors, the building of nuclear power plants and the sale of personal computers (PC). The first fraud consisted in underestimating and falsifying contract costs in order to make it seems like the project was profitable. Dutta and Lawson (2018) take the example of a 2012 government contract with Toshiba for a price of 7.1 billion yen that was estimated to cost the company 9 billion yen. Through anticipated cost reductions in their accounting, the company set the contract cost at 7 billion yen. The fraud was only revealed three years later. The company’s PC division also manipulated its operating profit through vast overestimations of transfer prices with its contract manufacturer. In a culture where meeting or exceeding targets is a duty, economic crises can push executives to try to hide losses or falsify earnings, but only a failing corporate governance could let such misbehavior go unchallenged for so many years.

Within the realm of corporate governance, instances of accounting fraud and financial window-dressing practices have often been rationalized and justified by the desire to maintain harmony within the company. Furthermore, the opportunity for fraud, which enables executives to execute their schemes without detection, has been identified as a significant contributing factor (Brown et al. 2016). In these cases, the opportunity for fraudulent activities arises from multiple corporate governance failures and a clear lack of effective internal control and regulation over executives’ decisions. While the Toshiba and Olympus cases have received considerable attention as prominent examples, they are accompanied by a broader range of corporate wrongdoing. For instance, the keiretsu Kanebo also became embroiled in an accounting fraud scandal that implicated their auditors, PricewaterhouseCoopers Chuo Aoyama, in their role in the fraudulent activities (Numata and Takeda 2010). Numerous other examples of such misconduct exist (Semba and Kato 2019; Skinner and Srinivasan 2012).

2.3.3. Corporate Governance Failures

Nakashima (2017) explored in an article the reasons and motivations of reported fraud in Japan over the period 2007–2015. To him, institutional incentives existed and were used to protect established firms’ authority and organization. Let’s explore some of the corporate governance failures that were revealed by Olympus and Toshiba’s frauds.

The main corporate governance frailties put forward by Dutta and Lawson (2018) are a lack of internal control, a weak system of audit caused by blurry separations of duties and emphasized by low workforce turnover. The researchers underline the fact that there was minimal job rotation at both Olympus and Toshiba, especially in key finance positions. This is justified by the companies by the fact that those top responsibilities post required highly qualified skills that only a few persons mastered. At both companies, Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) were also regularly appointed as heads of the Audit Office of Olympus, which once did not conduct a single audit of the finance department in 7 years. Moreover, the internal audit function in Japanese companies tends to only recommend changes in firms’ operational organization rather than correcting financial irregularities.

Ogawa (2017) states that boards of directors are usually organized into specific different committees in most of the developed economies, yet Japanese boards are mainly composed of company insiders that have often worked during the entirety of their career within the firm. In Toshiba’s case, some corporate governance best practices had been implemented. Independent directors even accounted for a quarter of the boards of directors that adopted US-style structures with distinct committees to control compensation, nomination, and auditing. However, the fact that those checks and balances did not work as intended was mainly because of the silence of most shareholders and little to no attention given to the few who raised issues. Activist funds are perceived as undesirable overseas organizations that risk disrupting the harmony of Japanese society. If external control was impossible, so was internal control, as no one from inside the company raised concerns. Lifetime employment is seen as a trade-off between job security and loyal obedience to the managers and the hierarchy. As reforms in Japan’s traditional corporate governance became increasingly necessary, Ogawa (2017) aptly concludes that governance is more about substance than mere form. Following the revelation in 2015 of Toshiba’s benefit overstatement, Japan took action by implementing a new Corporate Governance Code. In the next section, we will delve into some of these reforms and their implications.

3. Governance Reforms in Japan toward a Global Convergence?

Japan’s gradual adaptation of corporate governance ‘international standards’ has been scrutinized by both researchers and practitioners. Those different actors were commonly interested in knowing if Japan was doing progress in introducing more independent directors to its boards, improving its accounting standards and enabling more transparency in corporate behaviors or persevering in its traditional ways of doing business that we’ve reviewed earlier. For Hayashi (2013), while ownership and board structure certainly converge toward the Anglo-American style through reforms, the influence of the reforms on corporate governance is still limited.

3.1. Japan’s Recent Corporate Governance Evolution

3.1.1. A Wave of Corporate Governance Reforms and a Shift of Influence

As Passador (2016) explains it, corporate governance laws in Japan, and Japanese Law in general, is a hybrid adaptation of Roman-Germanic models with parts of US legal systems that were transplanted after the Second World War. In addition to that mix comes singular features related to the country’s historical, social, philosophical and economic heritage. The first Commercial Code was written in 1899 and significantly borrowed principles from the German equivalent of 1861, the Allgemeines Deutsches Handelsgesetzbuch. It was only after numerous corporate frauds and conflicts that several reforms were introduced to the country’s corporate governance. This time the influence came from Anglo-Saxon systems, notably with the redaction of the Corporate Governance Code in 2002–2003, the Corporate Law Reform of 2006 and the more recent reforms of 2014 and 2015.

In 2003, Japanese corporate law permitted businesses to select for the first time their governance system between four different structures: a general partnership (Gomei Gaisha), a limited partnership (Goshi Gaisha), a structure with limited liability based on the German model of GmbH divided into stocks and managed by both a board of directors and of auditors (Yugen Gaisha) and finally, a joint-stock company (Kabushiki Gaisha). This explanation is applicable to the corporate structure types before the Commercial Code amendment to create the current Corporate Law in 2006. After 2006, Yugen Gaisha was incorporated into Kabushiki Gaisha, and the new type Godo Gaisha, or Limited Liability Company, was introduced. In 2003, another reform aimed at producing incentives for firms to opt for a system of governance with boards composed of committees. Conform to Anglo-Saxon standards; committees are meant to improve the knowledge of the board in a certain area by focusing the responsibility for decisions in those areas on a smaller number of people (Gilson and Milhaupt 2005). Finally, and once again aligning itself to international best practices, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) presented in 2004 the “Principles of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies.” It was amended twice, in 2009 and 2015, and requires listed firms to explain and provide reasons for not respecting its principles.

After the Kanebo or Olympus scandal broke out, Japanese legislators became aware that firms did not have boards capable of checking and avoiding fraudulent conduct by their executives. Those scandals also brought to light the fact that strong conflict between minority shareholders and block shareholders, often members of the founding family, existed and were persistent. To tackle those issues, the Companies Act was introduced in 2015 as part of the ‘Japan Revitalization Strategy.’ It confirmed that the priorities for corporate governance reforms were both to review a firm’s ownership structure and to push for more independence and diversity of boards.

Let us have a closer look at the reforms in two main subject areas: ownership structure and board composition.

3.1.2. Ownership Structure in Japan

Japanese corporate governance first experienced a significant change in its ownership structure after the 1990s, when cross-shareholding began to diminish. Cross-shareholding was indeed one of the features that hindered Japan’s system from adopting corporate governance international best practices. Cross-shareholding, while enabling stable shareholding, prioritize corporate benefits over the maximization of dividend, which characterizes US-style governance. There are two frequent criticisms around cross-shareholding. The first is that it creates a non-efficient allocation of capital. The idea is that companies that sometimes hold a significant number of shares in an affiliated firm’s stock could invest their money with higher returns elsewhere on the market, hence participating in a better distribution of capital. A second reproach is that cross-holders generally compose a large part of voting shares that will almost always be in line with management. This provides unfair security to executives that can constantly underperform or ignore minority shareholders’ interests in their management, hence deepening agency costs (Dicko 2020). In fact, cross-shareholding renders a push for better management difficult and can deter tentative investor activism or hostile takeovers. An activist shareholder tries to take control of a company so as to push its management into making changes or simply replacing it. A hostile takeover occurs when one “acquirer” tries to buy a “target” company despite opposition from its board of directors. In 2016, around a third of Japanese listed companies’ stock was owned by “allegiant” investors, usually affiliated firms, banks, insurers, or founder’s families (Gedajlovic and Shapiro 2002; Limpaphayom et al. 2019).

The 2018 revised version of the Corporate Governance Code strongly urges cross holdings to be lowered. Lowering cross-shareholding is hoped to open Japan to institutional and foreign investors and to give stockholders a better chance of holding management accountable for either executive misdemeanors or poor company performance. Under the Corporate Governance Code, firms are compelled to disclose their cross-shareholding as the text states that boards should examine the mid to long-term rationale and future outlook of major cross-shareholdings on an annual basis, taking into consideration both associated risks and returns. The annual examination should result in the board’s detailed explanation of the objective and rationale behind cross-shareholdings (Tokyo Stock Exchange 2018). This measure is a consequence of the inclination to link management performance to economic performance and especially focus on return on equity (ROE) which is a key indicator from the shareholder perspective. Institutional and foreign investors, which compose a growing part of shareholders in Japan, are pushing for the unwinding of cross-shareholding ties. They advocate for companies to be more aware and careful of their balance sheet efficiencies. Indeed, comparative studies show that cross-shareholding is linked to poor governance and shareholder protection (Nguyen and Rahman 2020) as investors assume that companies would make suboptimal use of their capital and would rather have it distributed through dividends (for conceptual work and recent application to other countries see (Jiang 2019; Lee 2003)).

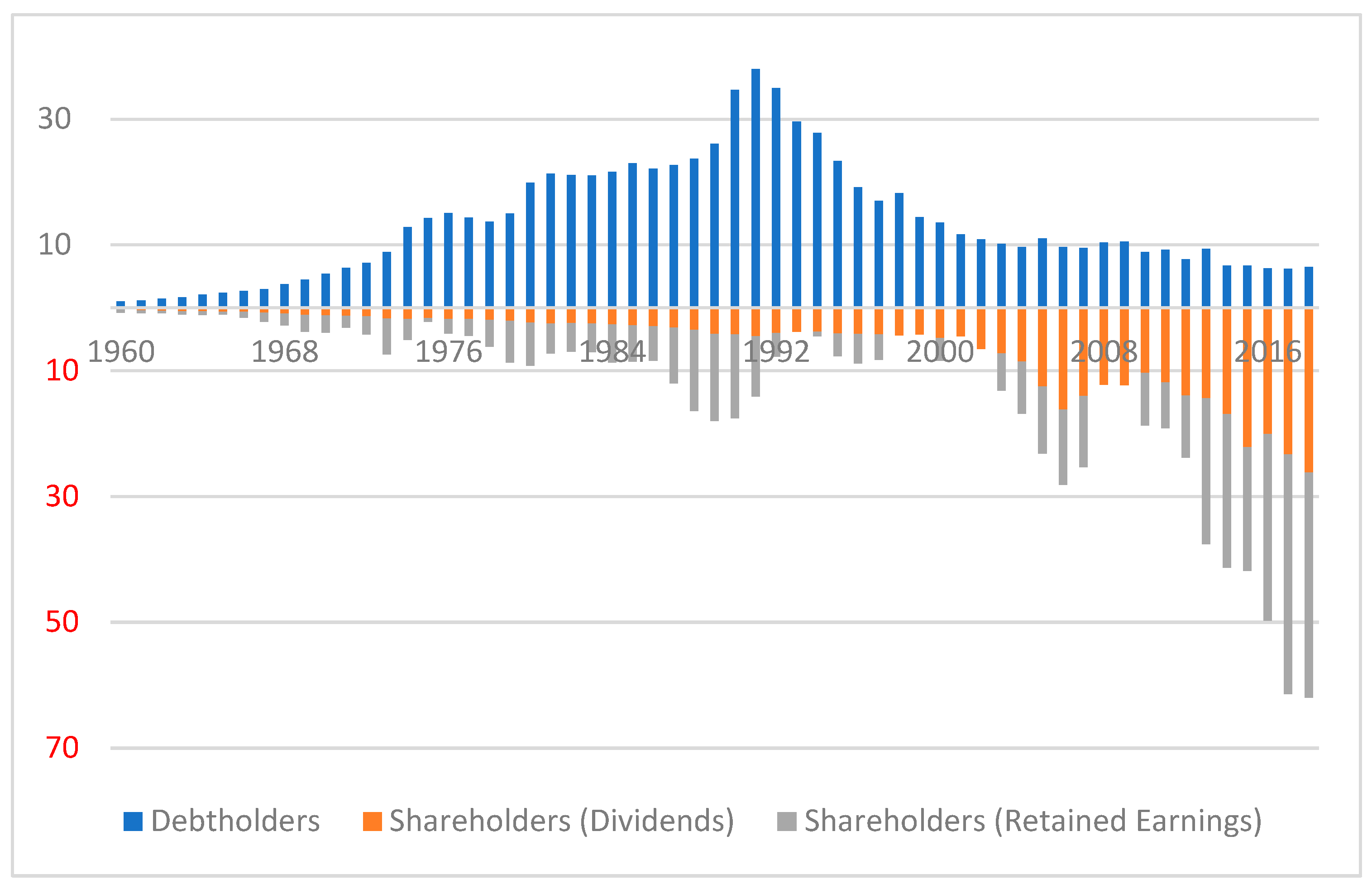

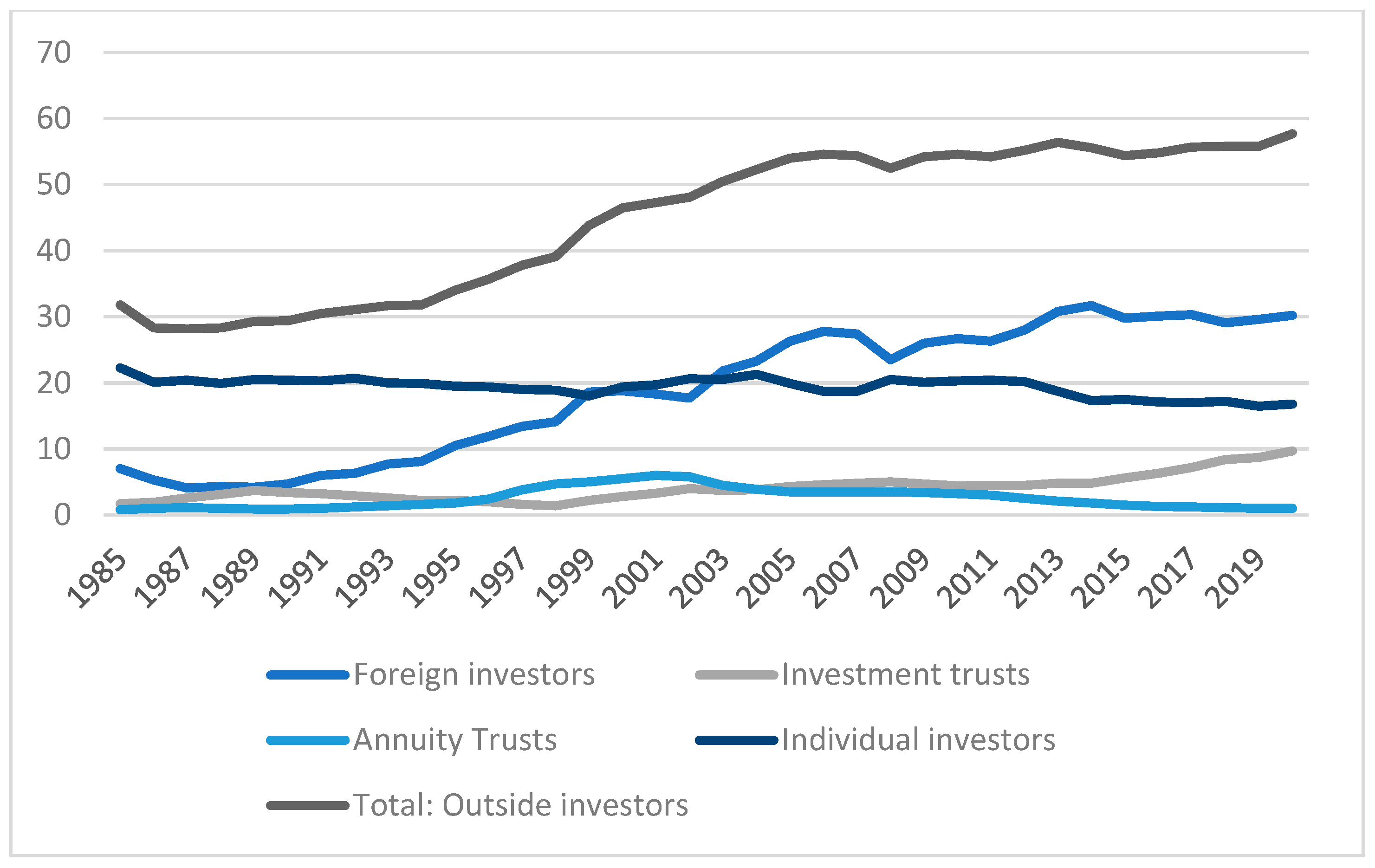

Another interesting trend in Japan’s corporate governance, from the financial perspective, is that equity stakeholders have taken the place of banks since the 1990s. Figure 1 shows the amount of corporate value added by the Japanese companies paid to the financial stakeholders (1 trillion yen); in 1991, around 32 trillion yen was paid to debtholders, mostly banks, and around 4 trillion was paid to shareholders, while in 2018, 6.5 trillion yen was paid to debtholders, and around 62 trillion to shareholders, a total inversion of the proportion. Banks, which historically have played an important role as the main source of external corporate financing until the 1990s, have seen their role diminish with the increasing importance of equity stakeholders providing financing and control. Traditionally, in a relationship-based financial system, main banks have long-term relationships with their clients that involve providing credit, maintaining equity stakes, and offering financial services and advice, but with a decreasing return on financing activities, their role has weakened since the early 1990s. Additionally, if we look at the ownership structure of listed companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, a similar pattern emerges. Figure 2 shows the holding ratios of foreign investors, individuals, investment trusts, and annuity trusts. We collectively name them outside investors, as opposed to banks and corporations, whose holding objective is to maximize investment returns. One of the most remarkable developments in ownership structure has been the sharp increase in foreign ownership, raising from 4.7% in 1985 to 30.2% in 2020, while the proportion of outside investors rose from 29.4% in 1990 to 57.7% in 2020. Institutional investors, especially foreigners, have played a more important role recently, while a bank-dominated structure and cross-shareholding are no longer defining characteristics of Japanese firms.

Figure 1.

The amount of corporate value added by the Japanese companies paid to the financial stakeholders (trillion yen). Source: Nozaki (2021) based on MoF corporate statistics.

Figure 2.

Ownership structure in Japan (percentage). Source: Adapted from the Share Ownership Survey, Japan Exchange Group, various years.

3.1.3. A Push toward More Independence on Boards of Directors

The Corporate Governance Code gives the board of directors a mission to hire and remove the management, to adopt business strategies, to assess risks taken, and to validate and oversee the choices of the managing team. Adopted in 2015, the code adopts a “comply or explain” rule that has been the standard in many corporate governance systems in developed countries. It is noticeable to see that the Council of Experts, which wrote the code, has been advised and monitored by the Financial Service Agency (FAS) and the TSE, which are both investor-protection-focused regulators (Litt 2015). The code requires companies to have at least two outside directors instead of one, as was the case previously. More importantly, it provides a range of guidance and advice to ensure the effectiveness of independent directors. Indeed, outside directors were present at Olympus but failed to prevent the scandal as they did not have the right support to fully achieve their supervising tasks. Ultimately it is the whole board that needs to be properly trained in order to give access to information and hear outsiders’ opinions. In fact, one of the weaknesses of the insider-dominated system was the lack of internal information sharing.

According to Litt (2015), a major proxy advisor, the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), has recommended to their members to vote against management decisions if the board of directors lacks at least one independent director. The ISS position has since been enforced, stipulating that members should reject the decision from the board lacking multiple outside directors. This willingness by institutional investors to play a more active role as shareholders was backed by the Abe government (2012–2020), which feared macroeconomic issues arising from mismanagement. Indeed, Japanese corporations tend to hoard cash and often fail to maximize their investment returns. Japanese pension funds are concerned that close to zero rates on debt instruments and poor returns on equities may obstruct them in meeting their commitments to pensioners as the country’s population is aging fast. In regard to that matter, a Stewardship Code for Japanese Institutional Investors was put in place in 2014. It aims at reallocating pension funds into Japanese equities to boost their performance. Corporate Governance reforms are proof of the acknowledgment by regulators that poor governance deters investments and lower share prices. Indeed, results from Nguyen and Rahman (2020) show that institutional investors have a prominent role in a company’s governance. However, Tasawar and Nazir (2019) found that some traditional business groups are trying to resist change, arguing that adding outside directors should not be mandatory and that there is no evidence of any link between corporate governance and corporate performance.

3.2. Limited and Difficult Compliance with International Standards

In this subsection, we investigate how the specific network/ecosystem organization of Japanese companies influenced the governance reforms.

3.2.1. A Persistent Differentiation on Corporate Governance Understanding

Many of Japan’s corporate governance reforms are being challenged by multiple resistances and oppositions, which could limit their concrete impact. A central reason for the reticence of Japanese corporations in applying the new principles may lie in a fundamentally different understanding of the core concept of corporate governance in comparison to Anglo-American companies. In 2019, when asked to explain in their annual reports their intentions for corporate governance, the TSE White Paper on Corporate Governance reported that “many companies expressed that the objective of corporate governance is the enhancement of corporate value,” reflecting a strong persistence of the stakeholder and an insider-centered view of corporate governance (Tokyo Stock Exchange 2019). Besides, only a few companies (6.4%) specified that shareholder value was an essential purpose of corporate governance, while 59.4% included serving stakeholders as a key objective. In an ever more globalized world, resistance to embracing standardized principles and behaviors is rare. The rather unique mindset of Japanese companies may be linked to what some observers have named the “Toyota effect.” During the 2000s, the Japanese car manufacturer was a symbol of the traditional keiretsu system and a fervent opponent of its reform. The group was advocating that the reason it was outperforming Sony was because the video game company had adopted an “American-style” corporate governance. Yoshimori (2005) explained that while holding on to the traditional lifetime employment model and despite having large-size and insider boards, Toyota outperformed General Motors even in the midst of the crisis of the 1990s. His research participated in anchoring the belief that corporate governance alone does not assure corporate performance and that values and culture might have played a bigger role. This argument is corroborated by recent empirical studies that challenge the legitimacy of adopting a one-size-fits-all approach in terms of corporate governance (Borah and James 2020).

3.2.2. Arising New Difficulties: Executive Remuneration

In Japan, both for managers and boards, the success of the corporation is a priority over the accumulation of individual or shareholder wealth. This rather unique feature of Japanese corporate governance is particularly reflected in the management of executive compensation. When Anglo-Saxon and European firms dedicate an increasing amount of time to looking for compensation packages that will maximize executives’ performance incentives, this issue is relatively irrelevant to Japanese firms.

However, the recent reforms in Japan have opened the country to more foreign executives who expect high compensation. To stick to the vision of the company community, newly internationalized boards sometimes use strategies to reduce executives’ pay on their annual reports, which raises concerns for all investors. The Nissan case is emblematic of the difficulties of modernizing the country’s governance procedures.

Following the arrest of C. Ghosn in November 2018, Nissan’s corporate governance practices came under fire and brought to light that despite the reforms, the country needed a stronger system of checks and balances to avoid governance failures and corporate scandals. The fact that Nissan can be seen as a laggard in complying with good governance principles is emblematic of the difficult compliance of Japan’s listed firms. The scandal also brought to light that introducing parts of the shareholder perspective, like trying to align incentives between stockholders and executives by raising their compensation, can lead to even more misbehaviors when done without proper internal controls. After the 2009 amendment of Japan’s ‘Principles of Corporate Governance,’ all listed companies became compelled to disclose executive compensation that went over 100 million yen. The focus of the controversy at Nissan is over the remuneration of former chairman C. Ghosn. The issue is whether or not Nissan violated Japan’s law by omitting to report his deferred compensation. Those deferred incomes were supposed to be received by C. Ghosn after his retirement and totaled 44 million US$. The Japanese Financial Services Agency stated that any fixed-amount payments, even deferred, were to be disclosed. Japanese prosecutors argue that internal Nissan documents proved that payments were fixed but not disclosed for at least 8 years, raising concerns regarding internal controls over public disclosures and the existence of an independent auditor monitoring those procedures.

Ultimately, the Ghosn affair demonstrated the need and value of boards structured into different committees and composed mainly of truly independent and competent directors. According to Pozen (2018), the nominating committee should find and recommend new directors; the audit committee should appoint the external auditor and review the company’s internal controls; and the compensation committee should set the criteria for executive pay in advance and explain the results to shareholders, “If Nissan’s governance procedures had followed these recommendations, it likely could have avoided the recent scandal” (Pozen 2018).

4. Conclusions

The globalization of corporate governance practices has undoubtedly influenced recent corporate reforms in Japan. But the complexity of its legal, societal, and cultural systems implies that the results of those reforms shaped a unique model rather than a copy of the Anglo-Saxon shareholder perspective. Too simplistic comparisons with the United Kingdom or the United States have led to erroneous assumptions about corporate Japan’s evolution. This paper showed that Japan’s corporate governance is an interesting case of a corporate system that proved to be capable of conducting technical prowess and manufacturing success during the country’s high-growth period but now seems to be dissonant in regard to an ever more globalized and standardized economy. Some researchers have proposed, as a reason for some of the current sluggish economic performances, a comparatively weak corporate governance system. Compared to other highly developed economies like the US or some European Union economies, corporate Japan is behind in almost all corporate governance features that aim at reducing agency costs, board independence, executive compensations, and shareholder activism.

Japanese firms are still structured more like families than profit machines, hence the prevalence of long-term, harmonious, and stable ownership. Corporate culture in Japan is strongly associated with group identity, and the concept of lifetime employment, even if it is receding, is still impregnated in the board of directors’ mindset. Despite far-reaching reforms, this unique perspective is still vivid, and Japan’s corporate culture proved to be far more resilient than what convergence theorists anticipated. In a global free-market logic, the inefficiencies that undermine Japan’s economy, such as low returns on investment or weak board oversight on management, should be instantly fixed. But the case of Japan highlights the fact that context and people matter and that convergent principles and frameworks don’t automatically give the same results everywhere. To witness an actual transformation in Japan, a change in mindset is as important as efforts to reform the regulatory framework. Therefore, authors like Nonaka and Takeuchi advocate for a wise company approach in Japan (Nonaka and Takeuchi 2019), recognizing the importance of knowledge creation and dissemination within organizations. On the other hand, Schembera et al. (2023) demonstrate through an impressive longitudinal study that improving the situation requires not only localized efforts but also nationwide changes in storytelling. Especially Schembera et al.’s research underscores the crucial role of storytelling in effecting broader changes in corporate governance. Storytelling serves as a powerful tool for shaping organizational culture, influencing decision-making processes, and fostering a shared understanding of governance principles. Their study highlights the need for coordinated efforts at both the local and national levels to implement storytelling practices that promote transparency, accountability, and ethical behavior within Japanese companies. Combining the insights from Nonaka’s wise company approach and Schembera et al.’s findings on storytelling, it becomes evident that a comprehensive transformation in corporate governance practices requires a multifaceted approach that encompasses knowledge creation, sharing, and communication strategies at various organizational and societal levels.

In the paper, we have defined some configurations of the Japanese model of governance and followed the changes that came in the last two decades as a result of long economic trends. But rather than looking at a de facto good or bad model of governance, especially through the prism of American-style standards, what is interesting is to understand the pressure for change and the feasibility of an alternative model of governance that might be quite difficult to initiate because of past institutional compromises. The facts and corporate scandals cited in this paper may be only illustrative, but we think that they point to considerable changes in the landscape of Japan’s corporate world. It is still difficult to see in which direction it is heading, but we could see two trends. First, there is an alignment on international best practices in terms of a firm’s ownership structure, and in pushing for more independence and diversity of boards, stable cross-shareholding is decreasing, and the role of independent auditors has been reinforced. Nevertheless, despite much talk about the importance of shareholders and the increase of dividends to the shareholders (Figure 1), the basic notion of stakeholder-oriented corporate governance still seems pervasive. For instance, the Keidanren, the Japanese Business Federation, in its 2017 revised Charter of Corporate Behaviour, urged its member companies to deliver on the SDGs by realizing Society 5.0, a government, business and academia plan to integrate new technological systems across various fields to the benefit of society (Carraz and Harayama 2019; Holroyd 2022). Since then, several researchers have proposed new ways of training students as well as senior managers in their understanding of corporate governance and control, as well as in utilizing financial documents and official statements effectively (Kinchin and Correia 2021; Le Corre and Burger-Helmchen 2022). Other scholars have proposed linking governance and control to knowledge management (Bollinger 2020) or utilizing the rise of sustainable development to drive new governance mechanisms (Neukam and Bollinger 2022).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R.; methodology, T.B.-H.; validation, R.C., T.B.-H.; formal analysis, T.R.; investigation, T.R.; resources, R.C.; data curation, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R.; writing—review and editing, R.C.; visualization, R.C.; supervision, T.B.-H.; project administration, T.B.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Partnership for the Organization of Innovation and New Technologies, funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada: 895-2018-1006.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilera, Ruth V., and Ilir Haxhi. 2019. Comparative Corporate Governance in Emerging Markets. In The Oxford Handbook of Management in Emerging Markets. Edited by Robert Grosse and Klaus K. Meyer. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Mike. 2022. Narrative Literature Review. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Masahiko. 1988. Information, Incentives, and Bargaining in the Japanese Economy, 1. paperback ed. Repr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, Masahiko. 2001. Toward a Comparative Institutional Analysis. Comparative Institutional Analysis. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, Masahiko, and Ronald Dore, eds. 1994. The Japanese Firm: The Sources of Competitive Strength. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, Masahiko, Gregory Jackson, and Hideaki Miyajima, eds. 2007. Corporate Governance in Japan: Institutional Change and Organizational Diversity. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, Bruce, and Joongi Kim, eds. 2019. Corporate Governance in Asia: A Comparative Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ballon, Robert J., and Iwao Tomita. 1989. Financial Behavior of Japanese Corporations. New York: Kodansha America. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Rob, Bart Frijns, Rogér Otten, and Alireza Tourani-Rad. 2008. The Impact of Corporate Governance on Corporate Performance: Evidence from Japan. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 16: 236–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Rob, Nadja Guenster, and Rogér Otten. 2004. Empirical Evidence on Corporate Governance in Europe: The Effect on Stock Returns, Firm Value and Performance. Journal of Asset Management 5: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, Sophie Raedersdorf. 2020. Creativity and Forms of Managerial Control in Innovation Processes: Tools, Viewpoints and Practices. European Journal of Innovation Management 23: 214–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, Nilakshi, and Hui James. 2020. Board Leadership Structure and Corporate Headquarters Location. Journal of Economics and Finance 44: 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, Robert. 2014. From ‘Japanophilia’ to Indifference? Three Decades of Research on Contemporary Japan. In The Great Transformation of Japanese Capitalism. Edited by Sebastien Lechevalier. Nissan Institute/Routledge Japanese Studies. London: Routledge, pp. xii, xxv. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, Robert, Hiroyasu Uemura, and Akinori Isogai. 2012. Diversity and Transformations of Asian Capitalisms. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bozec, Richard, and Yves Bozec. 2012. The Use of Governance Indexes in the Governance-Performance Relationship Literature: International Evidence: The Use of Governance Indexes in the Governance-Performance. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration 29: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Owen, Jerry Hays, and Martin T. Stuebs, Jr. 2016. Modeling Accountant Whistleblowing Intentions: Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Fraud Triangle. Accounting & The Public Interest 16: 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Helmchen, Thierry, and Erica J. Siegel. 2020. Some Thoughts On CSR in Relation to B Corp Labels. Entrepreneurship Research Journal 10: 20200231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, Michael, Marc Van Essen, Saul Estrin, and Daniel Shapiro. 2018. Business Groups Reconsidered: Beyond Paragons and Parasites. Academy of Management Perspectives 32: 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraz, Rene, and Yuko Harayama. 2019. Japan’s Innovation Systems at the Crossroads: Society 5.0. In Panorama: Insights into Asian and European Affairs. Singapore: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cernat, Lucian. 2004. The Emerging European Corporate Governance Model: Anglo-Saxon, Continental, or Still the Century of Diversity? Journal of European Public Policy 11: 147–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicko, Saidatou. 2020. Does Ownership Structure Influence the Relationship between Firms’ Political Connections and Financial Performance? International Journal of Corporate Governance 11: 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, Trung Quang, and Andrea Calabrò. 2019. Asian Family Firms through Corporate Governance and Institutions: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research. International Journal of Management Reviews 21: 50–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, Ronald. 1998. Asian Crisis and the Future of the Japanese Model. Cambridge Journal of Economics 22: 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, Ronald. 2005. Deviant or Different? Corporate Governance in Japan and Germany. Corporate Governance: An International Review 13: 437–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Saurav K., and Raef Lawson. 2018. Accouting Fraud at Japanese Companies: Ethical and Governance Failings Have Contributed to a Large Outbreak of Corporate Scandals in Japan. Strategic Finance 11: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- El-Helaly, Moataz, Nermeen F. Shehata, and Reem El-Sherif. 2018. National Corporate Governance, GMI Ratings and Earnings Management. Asian Review of Accounting 26: 373–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feils, Dorothee, Manzur Rahman, and Florin Şabac. 2018. Corporate Governance Systems Diversity: A Coasian Perspective on Stakeholder Rights. Journal of Business Ethics 150: 451–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukao, Mitsuhiro. 2003. Japan’s Lost Decade and Its Financial System. World Economy 26: 365–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedajlovic, Eric, and Daniel M. Shapiro. 2002. Ownership Structure and Firm Profitability in Japan. Academy of Management Journal 45: 565–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, Ronald J., and Curtis J. Milhaupt. 2005. Choice as Regulatory Reform: The Case of Japanese Corporate Governance. The American Journal of Comparative Law 53: 343–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. 1998. The Wages of Affluence: Labor and Management in Postwar Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guimtrandy, Fabien, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2022. The Pitch: Some Face-to-Face Minutes to Build Trust. Administrative Sciences 12: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, Taher, and Nada Mselmi. 2017. Corporate Governance and Equity Prices: The Effect of Board of Directors and Audit Committee Independence. Gobierno Corporativo y Precios de Las Acciones: Efecto de La Independencia de La Consejo de Administración y El Comité de Auditoría 21: 152–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Mizuki. 2013. Corporate Ownership and Governance Reforms in Japan: Influence of Globalization and U.s. Practice. Columbia Journal of Asian Law 26: 315–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, Shinichi, Katsuyuki Kubo, Hideaki Miyajima, Paul Hong, and Young Won Park. 2010. Corporate Mission, Corporate Policies and Business Outcomes: Evidence from Japan. Management Decision 48: 1134–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, Carin. 2022. Technological Innovation and Building a ‘Super Smart’ Society: Japan’s Vision of Society 5.0. Journal of Asian Public Policy 15: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, Takeo, and Anil Kashyap. 2001. Corporate Financing and Governance in Japan: The Road to the Future. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Huiqin. 2019. The Positions of the Stock Exchanges towards Listing with the Weighted Voting Rights Structure: A Comparative Study. Paper presented at the Corporate Law Teachers Association’ Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, February 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Kazuo, Meng Li, and Douglas J. Skinner. 2017. Is Japan Really a ‘Buy’? The Corporate Governance, Cash Holdings and Economic Performance of Japanese Companies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 44: 480–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Takao, and Katsuyuki Kubo. 2006. CEO Compensation and Firm Performance in Japan: Evidence from New Panel Data on Individual CEO Pay. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 20: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Takuma, and Mizuki Nishikawa. 2018. Ethical Leadership and Its Cultural and Institutional Context: An Empirical Study in Japan. Journal of Business Ethics 151: 707–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, Ian M., and Paulo R. M. Correia. 2021. Visualizing the Complexity of Knowledges to Support the Professional Development of University Teaching. Knowledge 1: 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Ryan, Michael C. Withers, and Matthew Semadeni. 2017. Compromise on the Board: Investigating the Antecedents and Consequences of Lead Independent Director Appointment. Academy of Management Journal 60: 2239–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Corre, Jean-Yves, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2021a. Rethinking Managerial Control in the Contemporary Context. In Integrated Science. Edited by Nima Rezaie. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 419–38. [Google Scholar]

- Le Corre, Jean-Yves, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2021b. Rethinking Managerial Control in the Contemporary Context: What Can We Learn from Recent Chinese Indigenous Management Research? In Engines of Economic Prosperity: Creating Innovation and Economic Opportunities through Entrepreneurship. Edited by Meltem Ince-Yenilmez and Burak Darici. London: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 303–21. [Google Scholar]

- Le Corre, Jean-Yves, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2022. Managerial Control in an Online Constructivist Learning Environment: A Teacher’s Perspective. Knowledge 2: 572–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Pey-Woan. 2003. Serving Two Masters—The Dual Loyalties of the Nominee Director in Corporate Groups. Journal of Business Law 9: 449. [Google Scholar]

- Lechevalier, Sébastien. 2014. The Great Transformation of Japanese Capitalism. Nissan Institute/Routledge Japanese Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Limpaphayom, Piman, Daniel A. Rogers, and Noriyoshi Yanase. 2019. Bank Equity Ownership and Corporate Hedging: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Corporate Finance 58: 765–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, David G. 2015. Japan’s New Corporate Governance Code: Outside Directors Find a Role Under ‘Abenomics’. Corporate Governance Advisor 23: 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Qi, and Toyohiko Hachiya. 2005. Corporate Governance, Cash Holdings, and Firm Value:: Evidence from Japan. Review of Pacific Basin Financial Markets & Policies 8: 613–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, Yoshiro, and J. Mark Ramseyer. 2002. Banks and Economic Growth: Implications from Japanese History. The Journal of Law and Economics 45: 127–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, Randall, and Masao Nakamura. 1999. Banks and Corporate Control in Japan. The Journal of Finance 54: 319–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, Randall, Masao Nakamura, and M. Frank. 2001. Japanese Corporate Governance and Macroeconomic Problems. In The Japanese Business and Economic System. Edited by M. Nakamura. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 325–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Masao. 2015. Economic Development and Business Groups in Asia: Japan’s Experience and Implications. International Advances in Economic Research 21: 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, Masumi. 2017. Can The Fraud Triangle Predict Accounting Fraud? Evidence from Japan 2017. Paper present at the 8th International Conference of the Japanese Accounting Review, Kobe, Japan, January 6. [Google Scholar]

- Neukam, Marion, and Sophie Bollinger. 2022. Encouraging Creative Teams to Integrate a Sustainable Approach to Technology. Journal of Business Research 150: 354–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Pascal, and Nahid Rahman. 2020. Institutional Ownership, Cross-shareholdings and Corporate Cash Reserves in Japan. Accounting & Finance 60: 1175–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Hiro Takeuchi. 1995. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, Ikujiro, and Hiro Takeuchi. 2019. The Wise Company: How Companies Create Continuous Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki, Hironari. 2021. Chiiki Kinyu No Yukue (Outlook of Regional Finance), Keizai Kyoshitsu. Nikkei Newspaper, December 27. [Google Scholar]

- Numata, Shingo, and Fumiko Takeda. 2010. Stock Market Reactions to Audit Failure in Japan: The Case of Kanebo and ChuoAoyama. International Journal of Accounting (World Scientific Publishing Company) 45: 175–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Alicia. 2017. Toshiba and the Myth of Corporate Governance. Columbian Business School Working Paper. New York: Center on Japanese Economy and Business. [Google Scholar]

- Okumura, Ariyoshi. 2004. A Japanese View on Corporate Governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 12: 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olympus Corporation. 2011. Olympus Corporation Third Party Committee, 2011. Investigation Report. Available online: https://www.olympus-global.com/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Passador, Maria Lucia. 2016. Corporate Governance Models: The Japanese Experience in Context. DePaul Business & Commercial Law Journal 15: 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pozen, Robert C. 2018. Carlos Ghosn, Nissan, and the Need for Stronger Corporate Governance in Japan. Harvard Business Review Digital Articles 12: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Schembera, Stefan, Patrick Haack, and Andreas Georg Scherer. 2023. From Compliance to Progress: A Sensemaking Perspective on the Governance of Corruption. Organization Science 34: 1184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, Hu Dan, and Ryo Kato. 2019. Does Big N Matter for Audit Quality? Evidence from Japan. Asian Review of Accounting 27: 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, Kaori. 2018. Hyoe Yamamoto Dives into Japan’s Culture of Corporate Corruption in ‘Samurai and Idiots: The Olympus Affair’. The Japan Times. May 16. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2018/05/16/films/hyoe-yamamoto-dives-japans-culture-corporate-corruption-samurai-idiots-olympus-affair/ (accessed on 2 February 2023.).

- Skinner, Douglas J., and Suraj Srinivasan. 2012. Audit Quality and Auditor Reputation: Evidence from Japan. Accounting Review 87: 1737–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songini, Lucrezia, and Luca Gnan. 2015. Family Involvement and Agency Cost Control Mechanisms in Family Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management 53: 748–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasawar, Anam, and Mian Sajid Nazir. 2019. The Nexus between Effective Corporate Monitoring and CEO Compensation. International Journal of Corporate Governance 10: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuhiro, Kishita. 2013. Corporate Governance in Established Japanese Firms: Will the Olympus Scandal Happen Again? Journal of Enterprising Culture 21: 421–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokyo Stock Exchange. 2018. Japan’s Corporate Governance Code Seeking Sustainable Corporate Growth and Increased Corporate Value over the Mid- to Long-Term. Tokyo: Tokyo Stock Exchange. [Google Scholar]

- Tokyo Stock Exchange. 2019. White Paper on Corporate Governance. Tokyo: Tokyo Stock Exchange. [Google Scholar]

- Vig, Shinu, and Manipadma Datta. 2018. Reviewing and Revisiting the Use of Corporate Governance Indices. International Journal of Corporate Governance 9: 227–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimori, Masaru. 2005. Does Corporate Governance Matter? Why the Corporate Performance of Toyota and Canon Is Superior to GM and Xerox. Corporate Governance: An International Review 13: 447–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).