Mechanisms of Organizational Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Engagement: A Multi-Level Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mindfulness

2.2. Employee Engagement

2.3. Mindfulness and Engagement

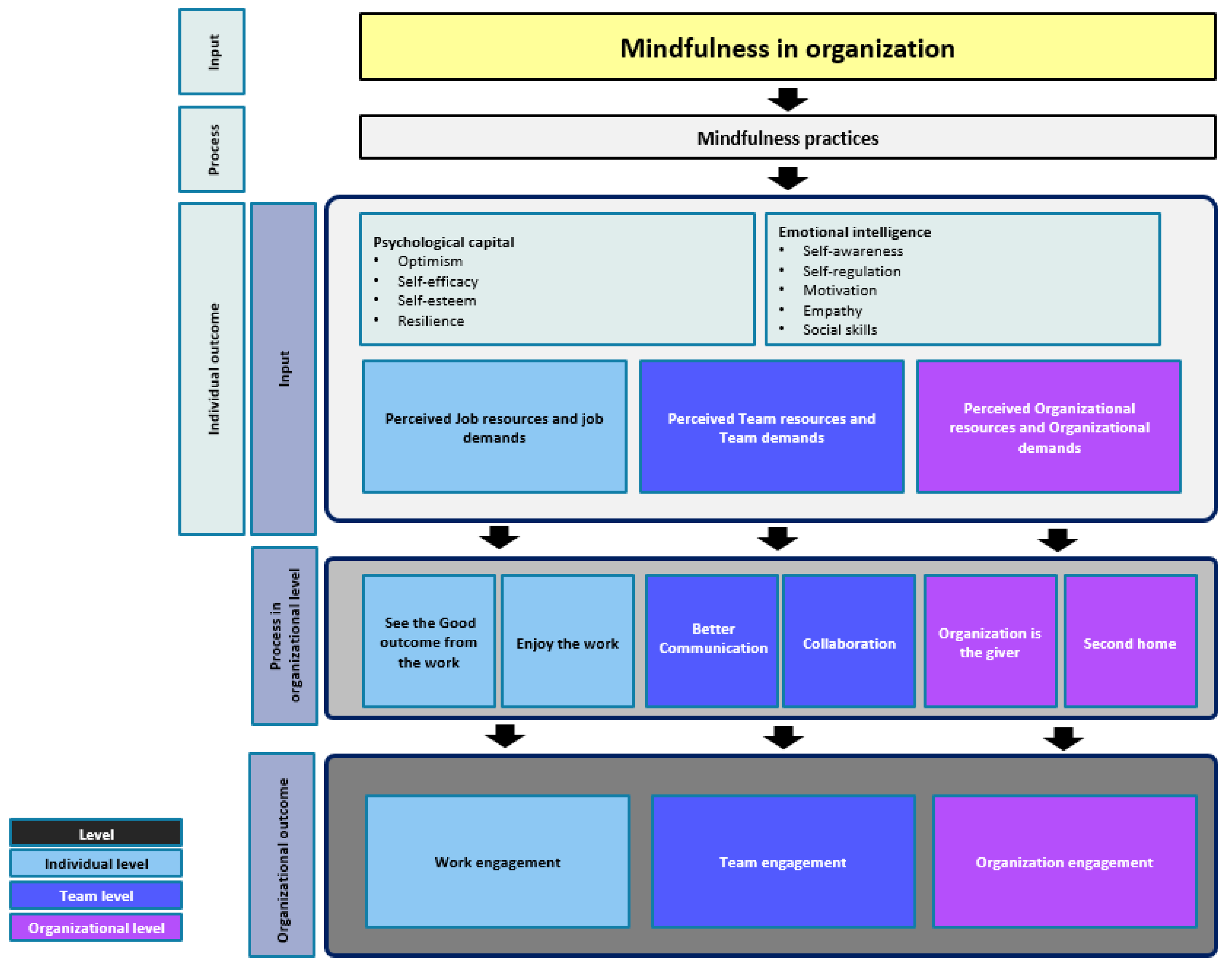

2.4. Mindfulness in Organizations (MIO) Development Program

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitation and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adair, Kathryn C., Barbara L. Fredrickson, Laura Castro-Schilo, Sumi Kim, and Stephania Sidberry. 2018. Present with You: Does Cultivated Mindfulness Predict Greater Social Connection Through Gains in Decentering and Reductions in Negative Emotions? Mindfulness 9: 737–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, Kimberly A., John Astin, Kenneth R. Pelletier, Kristin Levanovich, Catherine M. Baase, Yeo Yung Park, and Catherine M. Bodnar. 2014. Mindfulness Goes to Work: Impact of an Online Workplace Intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56: 721–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, Jagannathan. 2014. Determinants of Employee Engagement and Their Impact on Employee Performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 63: 308–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antanaitis, Arunas. 2015. Mindfulness in the Workplace Benefits and Strategies to Integrate Mindfulness-Based Programs in the Workplace. Journal: The Official Publication of the Ontario Occupational Health Nurses Association 34: 39. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, Katherine M., Aiden Cope, and Alison Liebling. 2017. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Yoga and Mindfulness Meditation in Prison: Effects on Psychological Well-Being and Behavioural Functioning. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 61: 689–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2017. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Patrícia L. Costa. 2014. Chronic Job Burnout and Daily Functioning: A Theoretical Analysis. Burnout Research 1: 112–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Yiqing Wang. 2020. Self-undermining behavior at work: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Int. J. Stress Manage. 27: 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and Ana Isabel Sanz-Vergel. 2014. Burnout and Work Engagement: The JD–R Approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1: 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and Ana Sanz-Vergel. 2023. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 10: 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2003. The Socially Induced Burnout Model. Leading Edge Research in Cognitive Psychology 25: 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, Louis, Véronique Rouleau, Simon Grégoire, and Charles Baron. 2018. Mindfulness and Leadership Flexibility. Journal of Management Development 37: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Dana. 2013. One Nation under Stress: The Trouble with Stress as an Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Daniel R., Athena H. Cairo, Robert J. Goodman, Jordan T. Quaglia, Jeffrey D. Green, and Kirk Warren Brown. 2018. Mindfulness increases prosocial responses toward ostracized strangers through empathic concern. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 147: 93. [Google Scholar]

- Bränström, Richard, Pia Kvillemo, Yvonne Brandberg, and Judith Tedlie Moskowitz. 2010. Self-Report Mindfulness as a Mediator of Psychological Well-Being in a Stress Reduction Intervention for Cancer Patients—A Randomized Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 39: 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, William, Sarah Hankerson, Sangwon Byun, and Birdie Cunningham. 2016. Cultivating Leadership Dharma: Measuring the Impact of Regular Mindfulness Practice on Creativity, Resilience, Tolerance for Ambiguity, Anxiety and Stress. Journal of Management Development 35: 1056–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kirk Warren, and Richard M. Ryan. 2003. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kirk Warren, Richard M. Ryan, and J. David Creswell. 2007. Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for Its Salutary Effects. Psychological Inquiry 18: 211–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Annemaree, Emma Sanders-O’Connor, Kylee Forrest, Samuel Fynes-Clinton, Ashley York, Maryam Ziaei, Libby Flynn, Julie Majella Bower, and David Reutens. 2022. Improving Emotion Regulation, Well-Being, and Neuro-Cognitive Functioning in Teachers: A Matched Controlled Study Comparing the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Health Enhancement Programs. Mindfulness 13: 123–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Vickie Y., Oxana Palesh, Rebecca Caldwell, Nathan Glasgow, Mark Abramson, Frederic Luskin, Michelle Gill, Adam Burke, and Cheryl Koopman. 2004. The Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program on Stress, Mindfulness Self-Efficacy, and Positive States of Mind. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress 20: 141–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Yun-Chen, Chang-Fang Chiu, Chih-Kai Wang, Chen-Teng Wu, Liang-Chih Liu, and Yao-Chung Wu. 2022. Short-Term Effect of Internet-Delivered Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Mental Health, Self-Efficacy, and Body Image among Women with Breast Cancer during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 949446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, Peerayuth, and Jenette Villegas Puyod. 2022. Mindfulness and Emotional Exhaustion in Call Center Agents in the Philippines: Moderating Roles of Work and Personal Characteristics. The Journal of General Psychology 149: 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Lingwei, Chien-Chung Huang, and Sophie Sitar. 2023. Mindfulness and Job Performance in Chinese Nonprofit Workers: Mediation Effects of PANA and Work Engagement. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, Alberto, and Alessandro Serretti. 2010. A Systematic Review of Neurobiological and Clinical Features of Mindfulness Meditations. Psychological Medicine 40: 1239–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Brian, Jerry Slutsky, Julianna Raye, and John David Creswell. 2019. Mindfulness Training Reduces Stress at Work: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 10: 627–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, Michael S., Adela S. Garza, and Jerel E. Slaughter. 2011. Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Personnel Psychology 64: 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, Paul. 2017. Mindfulness, Compassion, and Prosocial Behaviour. In Mindfulness in Social Psychology. London: Routledge, pp. 132–46. [Google Scholar]

- Coo, Cristián, and Marisa Salanova. 2018. Mindfulness Can Make You Happy-and-Productive: A Mindfulness Controlled Trial and Its Effects on Happiness, Work Engagement and Performance. Journal of Happiness Studies 19: 1691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. David, Naomi Eisenberger, and Matthew Lieberman. 2008. Neural Correlates of Mindfulness during Social Exclusion. Paper presented at 3rd Annual Conference on Integrating Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Interventions into Medicine, Health Care, and Society, Worcester, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, Russell, and Marie S. Mitchell. 2005. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management 31: 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, Erik. 2011. Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in the workplace. Journal of Management 37: 997–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, Erik, and Bradley J. Brummel. 2014. Examining Workplace Mindfulness and Its Relations to Job Performance and Turnover Intention. Human Relations 67: 105–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, and Russell Cropanzano. 2010. From Thought to Action: Employee Work Engagement and Job Performance. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. Edited by A. B. Bakker and Michael P. Leiter. London: Psychology Press, vol. 65, pp. 147–63. [Google Scholar]

- Forjan, Danielle N., Michelle R. Tuckey, and Yiqiong Li. 2020. Problem Solving and Affect as Mechanisms Linking Daily Mindfulness to Task Performance and Job Satisfaction. Stress and Health 36: 338–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, Theresa M., Michelle K. Duffy, Joyce E. Bono, and Tao Yang. 2011. Mindfulness at Work. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 30: 115–57. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1996. Emotional Intelligence. Why It Can Matter More than IQ. Learning 24: 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel. 2013. Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- González-Palau, Fátima, and Leonardo Adrián Medrano. 2022. A Mini-Review of Work Stress and Mindfulness: A Neuropsychological Point of View. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 854204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, Darren J., Christopher J. Lyddy, Theresa M. Glomb, Joyce E. Bono, Kirk Warren Brown, Michelle K. Duffy, Ruth A. Baer, Judson A. Brewer, and Sara W. Lazar. 2016. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work: An Integrative Review. Journal of Management 42: 114–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecucci, Alessandro, Edoardo Pappaianni, Roma Siugzdaite, Anthony Theuninck, and Remo Job. 2015. Mindful Emotion Regulation: Exploring the Neurocognitive Mechanisms behind Mindfulness. BioMed Research International 2015: 670724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Arnold B. Bakker, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2006. Burnout and Work Engagement among Teachers. Journal of School Psychology 43: 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, Silja, Matthias Weiss, Alexander Newman, and Martin Hoegl. 2020. Resilience in the Workplace: A Multilevel Review and Synthesis. Applied Psychology 69: 913–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, Fereshteh, Fariborz Dortaj, Noorali Farrokhi, and Bita Nasrollahi. 2020. Effectiveness of Mindfulness Training on Components of Students’ Academic Optimism (Social Confidence, Academic Emphasis and Identity Sense). Scientific Journal of Social Psychology 7: 101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2002. Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Review of General Psychology 6: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Robert J. Johnson, Nicole Ennis, and Anita P. Jackson. 2003. Resource Loss, Resource Gain, and Emotional Outcomes among Inner City Women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 632–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivtzan, Itai, Tarli Young, Janis Martman, Allison Jeffrey, Tim Lomas, Rona Hart, and Francisco Jose Eiroa-Orosa. 2016. Integrating Mindfulness into Positive Psychology: A Randomised Controlled Trial of an Online Positive Mindfulness Program. Mindfulness 7: 1396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, Stephanie D., and Michelle R. Tuckey. 2017. Mindfulness Interventions in the Workplace: A Critique of the Current State of the Literature. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22: 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbehdar Nourafkan, Nadia, Cem Tanova, and Korhan K. Gokmenoglu. 2023. Can Mindfulness Improve Organizational Citizenship and Innovative Behaviors Through Its Impact on Well-Being Among Academics? Psychological Reports 126: 2027–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 1990. Full Catastrophe Living: The Program of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York: Delta. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, William A. 1990. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Academy of Management Journal 33: 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katan, Naama, Shay Tzafrir, and Enosh Guy. 2019. Effect of Mindfulness Practice on Self-Efficacy Among Employees in an Organization. Academy of Management Proceedings 2019: 13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, Maryanna D., Janet Buckworth, and William B. Malarkey. 2009. Effects of Low-Dose Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR-Ld) on Working Adults. Health Education & Behavior 36: 601–14. [Google Scholar]

- Klatt, Maryanna, Beth Steinberg, and Anne-Marie Duchemin. 2015. Mindfulness in Motion (MIM): An Onsite Mindfulness Based Intervention (MBI) for Chronically High Stress Work Environments to Increase Resiliency and Work Engagement. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE, e52359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlbacher, Florian. 2006. The Use of Qualitative Content Analysis in Case Study Research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 7: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfield, Jack. 2012. Teachings of the Buddha. Boulder: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kwarteng, Samuel, Samuel Oti Frimpong, Richard Asare, and Twumasi Jacob Nana Wiredu. 2024. Effect of Employee Recognition, Employee Engagement on Their Productivity: The Role of Transformational Leadership Style at Ghana Health Service. Current Psychology 43: 5502–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, Emily J., Michelle R. Tuckey, and Maureen F. Dollard. 2018. Job Design for Mindful Work: The Boosting Effect of Psychosocial Safety Climate. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 23: 483–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Jihyun, Kwan Hoon Kim, Craig S. Webster, and Marcus A. Henning. 2021. The Evolution of Mindfulness from 1916 to 2019. Mindfulness 12: 1849–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, Hannes, Frederik Anseel, Nicoletta G. Dimitrova, and Luc Sels. 2013. Mindfulness, Authentic Functioning, and Work Engagement: A Growth Modeling Approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior 82: 238–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Shengmin, Huanhuan Xin, Li Shen, Jianjia He, and Jingfang Liu. 2020. The Influence of Individual and Team Mindfulness on Work Engagement. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xuepeng, Qing Wang, and Zhenzhen Zhou. 2022. The Association between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 14: 10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Zihan, Kevin Hoff, Erica Baranski, Galen Snyder, Rhona Flin, Peggy Lindner, and Christiane Spitzmueller. 2023. Mindfulness and Workplace Safety: An Integrative Review. Journal of Organizational Behavior 44: 1263–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Carolyn M. Youssef-Morgan. 2017. Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 4: 339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, Peter, and Hui Jia Lim. 2015. Mindfulness at Work: Positive Affect, Hope, and Optimism Mediate the Relationship between Dispositional Mindfulness, Work Engagement, and Well-Being. Mindfulness 6: 1250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelsen, Maren M., Johannes Graser, Miriam Onescheit, Matthias P. Tuma, Lena Werdecker, Dawid Pieper, and Tobias Esch. 2023. Mindfulness-Based and Mindfulness-Informed Interventions at the Workplace: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness 14: 1271–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Motevalli, Saeid, Hannaneh Mohammadbeigi Salahshour, and Richard Peter Bailey. 2023. The Mediating Role of Cognitive Flexibility in the Relationship between Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies and Mindfulness in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Affective Disorders 339: 676–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuber, Lina, Colinda Englitz, Niklas Schulte, Boris Forthmann, and Heinz Holling. 2022. How Work Engagement Relates to Performance and Absenteeism: A Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 31: 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Cao Minh Anh, and Minh-Tri Ha. 2023. The Interplay between Internal Communication, Employee Engagement, Job Satisfaction, and Employee Loyalty in Higher Education Institutions in Vietnam. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhy, Meera, Prabhati Pati, and Sandra Roshni Monteiro. 2021. Well-Being Indices: A Role of Mindfulness and Social Support. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20210504006 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Purser, Ronald E. 2018. Critical perspectives on corporate mindfulness. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 15: 105–8. [Google Scholar]

- Querstret, Dawn, Linda Morison, Sophie Dickinson, Mark Cropley, and Mary John. 2020. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Health and Well-Being in Nonclinical Samples: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Stress Management 27: 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, Aleksandar, Juan M. Arjona-Fuentes, Antonio Ariza-Montes, Heesup Han, and Rob Law. 2020. Job Demands–Job Resources (JD-R) Model, Work Engagement, and Well-Being of Cruise Ship Employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management 88: 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, Jochen, Jayanth Narayanan, and Zhi Wei Ho. 2015. Mindfulness at Work: Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Awareness and Absent-Mindedness. Mindfulness 6: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, Christopher S., Glen E. Kreiner, Alexandra Rheinhardt, and Christine A. Mihelcic. 2022. Your Presence Is Requested: Mindfulness Infusion in Workplace Interactions and Relationships. Organization Science 34: 722–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, Megan, Lee Waller, Michael Chaskalson, Sharon Olivier, and Silke Rupprecht. 2020. Developing Leaders through Mindfulness Practice. Journal of Management Development 39: 223–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., James N. Donald, and Emma L. Bradshaw. 2021. Mindfulness and Motivation: A Process View Using Self-Determination Theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science 30: 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M. 2006. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology 21: 600–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M. 2019. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance 6: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M. 2022. Caring Human Resources Management and Employee Engagement. Human Resource Management Review 32: 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M., and Jamie A. Gruman. 2014. What Do We Really Know about Employee Engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly 25: 155–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B. 2012. Work Engagement: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology 14: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, Wahab, and Jane Parker. 2022. Workplace Mindfulness: An Integrative Review of Antecedents, Mediators, and Moderators. Human Resource Management Review 32: 100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, Rebecca, Damien Tessier, Lionel Strub, Aurélie Gauchet, and Céline Baeyens. 2021. Improving Mental Health and Well-Being through Informal Mindfulness Practices: An Intervention Study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 13: 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, Shauna L., Margaret C. Wang, and Emily H. Peltason. 2015. What Is Mindfulness, and Why Should Organizations Care about It. In Mindfulness in Organizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Strohmaier, Sarah, Fergal W. Jones, and James E. Cane. 2022. One-Session Mindfulness of the Breath Meditation Practice: A Randomized Controlled Study of the Effects on State Hope and State Gratitude in the General Population. Mindfulness 13: 162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Li, and Chanchai Bunchapattanasakda. 2019. Employee Engagement: A Literature Review. International Journal of Human Resource Studies 9: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Sara B., Lindsay A. Kennedy, Caroline E. Lee, and Emily K. Waller. 2022. Common Humanity in the Classroom: Increasing Self-Compassion and Coping Self-Efficacy through a Mindfulness-Based Intervention. Journal of American College Health 70: 142–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Paul. 2020a. Employee Engagement in Contemporary Organizations: Maintaining High Productivity and Sustained Competitiveness. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Paul. 2020b. Why Is Employee Engagement Important? In Employee Engagement in Contemporary Organizations. Cham: Springer, pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ucok, Ozum. 2006. Transparency, Communication and Mindfulness. Edited by Tom McManus, Yair Holtzman, Harold Lazarus, and Johan Anderberg. Journal of Management Development 25: 1024–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderlin, Ruben, Miriam Biermann, Martin Bohus, and Lisa Lyssenko. 2020. Mindfulness-Based Programs in the Workplace: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Mindfulness 11: 1579–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Zack. 2016. A Meta-Critique of Mindfulness Critiques: From McMindfulness to Critical Mindfulness. In Handbook of Mindfulness. Cham: Springer, pp. 153–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpiromsanti, Yongyud. 2017. Speaker’s Manual: Course on Creating Happiness with Mindfulness in Organizations (Mindfulness in Organization: MIO) [Manual in Thai]. Available online: https://www.dmh-elibrary.org/items/show/335 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Xanthopoulou, Despoina, Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2009. Reciprocal Relationships between Job Resources, Personal Resources, and Work Engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior 74: 235–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, Nur Hani, and Michelle G. Newman. 2024. Mindfulness Enhances Cognitive Functioning: A Meta-Analysis of 111 Randomized Controlled Trials. Health Psychology Review 18: 369–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Dexing, Eric K. P. Lee, Eva C. W. Mak, Chi Y. Ho, and Samuel Y. S. Wong. 2021. Mindfulness-Based Interventions: An Overall Review. British Medical Bulletin 138: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Jingyu, and Changxu Wu. 2014. The Influence of Dispositional Mindfulness on Safety Behaviors: A Dual Process Perspective. Accident Analysis & Prevention 70: 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xiaoming, Dan Ni, Xin Liu, and Lindie H. Liang. 2023. Workplace Mindfulness: Multidimensional Model, Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Business and Psychology 38: 777–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Author | Article | Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research | Related to Occupational Setting | Work Engagement | Employee Engagement | Number of Respondents | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Aikens et al. 2014) | Mindfulness Goes to Work Impact of an On-Line Workplace Intervention | ✓ | ✓ | 89 | Mindfulness is positively related to work engagement, vigor, and resiliency, but is negatively related to stress. | |||

| 2 | (Dane and Brummel 2014 ) | Examining workplace mindfulness and its relations to job performance and turnover intention | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 102 | Mindfulness can improve job performance and reduced turnover intention, but it is not significant regarding work engagement. | ||

| 3 | (Glomb et al. 2011) | Mindfulness at Work | ✓ | ✓ | 20 | Mindfulness can enhance employee performance and well-being | |||

| 4 | (Klatt et al. 2009) | Effects of Low-Dose Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR-ld) on Working Adults | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | Mindfulness can reduce perceived stress. | |||

| 5 | (Klatt et al. 2015) | Mindfulness in Motion (MIM): An Onsite Mindfulness Based Intervention (MBI) for Chronically High Stress Work Environments to Increase Resiliency and Work Engagement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 34 | Mindfulness can increase resilience and work engagement. | ||

| 6 | (Leroy et al. 2013) | Mindfulness, authentic functioning, and work engagement: Agrowth modeling approach | ✓ | ✓ | 90 | Mindfulness is positively related with work engagement. | |||

| 7 | (Malinowski and Lim 2015) | Mindfulness at work: Positive affect, hope, and optimism mediate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, work engagement and well-being | ✓ | ✓ | 291 | Mindfulness can increase work engagement, hope, and optimism. | |||

| 8 | (Michaelsen et al. 2023) | Mindfulness-Based and Mindfulness-Informed Interventions at the Workplace: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis of RCTs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9375 | Mindfulness interventions are generally effective and serve as a valuable means to improve various aspects of employee health. | ||

| 9 | (Neuber et al. 2022) | How Work Engagement Relates to Performance and Absenteeism: A Meta-Analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 139,182 | Work engagement is positively associated with future task performance and negatively associated with future absenteeism. | ||

| 10 | (Vonderlin et al. 2020) | Mindfulness-Based Programs in the Workplace: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. | ✓ | ✓ | 5161 | It is evident that mindfulness-based programs can effectively promote good health and well-being of employees across various occupational settings. | |||

| 11 | (Zainal and Newman 2024) | Mindfulness Enhances Cognitive Functioning: A Meta-Analysis of 111 Randomized Controlled Trials. | ✓ | 9538 | Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) can consistently produce small-to-moderate, yet practically significant, effects on global cognition and six cognitive subdomains. |

| JD-R Component | Factors | Potential Path and Rationale | Psychological Conditions (Kahn 1990) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal resources | Hope (Strohmaier et al. 2022) | Mindfulness practice can enhance an individual’s state of hope (Strohmaier et al. 2022). | |

| Optimism (Hashemi et al. 2020) | Mindfulness decreases the focus on negative thinking and improves optimism (Hashemi et al. 2020). | ||

| Self-efficacy (Taylor et al. 2022) | Individuals can advance self-efficacy through the development of mindfulness practices (Taylor et al. 2022). | Psychological availability (Kahn 1990) | |

| Resilience (Liu et al. 2022) | Resilience is likely to be more prominent in mindful individuals since they tend to engage less in rumination and habitual worrying (Liu et al. 2022). | ||

| Resources | Autonomy (Ryan et al. 2021) | There is a positive association between autonomy and mindfulness (Ryan et al. 2021). | Meaningfulness (Kahn 1990) |

| Social support (Padhy et al. 2021) | The study results demonstrated a positive correlation between mindfulness and social support (Padhy et al. 2021). | Psychological safety (Kahn 1990) | |

| Psychological safety climate (Lawrie et al. 2018) | Mindful work could enhance psychological safety climate (Lawrie et al. 2018). | Psychological safety (Kahn 1990) | |

| Demands | Perceived stress (Querstret et al. 2020) | Mindfulness practices lessen stress (Querstret et al. 2020) and can alleviate perceived job demands. |

| Interviewee Demographics and Professional Details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Interviewees | % | ||

| Age | 20–30 Years | 1 | 4% |

| 31–40 Years | 8 | 30% | |

| 41–50 Years | 11 | 41% | |

| Over 50 Years | 7 | 26% | |

| Gender | Male | 14 | 52% |

| Female | 13 | 48% | |

| Education | Grade 6 | 1 | 4% |

| Grade 9 | 3 | 11% | |

| Grade 12 | 6 | 22% | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 12 | 44% | |

| Master’s Degree | 1 | 4% | |

| Vocational Certificate | 4 | 15% | |

| Job position | Manager | 11 | 41% |

| Employee | 16 | 59% | |

| Occupation | Production personnel and inventory | 8 | 30% |

| Financial and accounting | 6 | 22% | |

| Sales and customer service | 7 | 26% | |

| Quality assurance and diagnostic office | 2 | 7% | |

| Research and marketing planning officer | 1 | 4% | |

| Engineering manager | 1 | 4% | |

| Procurement personnel | 1 | 4% | |

| Director | 1 | 4% | |

| JD-R Component | Resultant Nodes | |

|---|---|---|

| Resources | Job level | Awareness in resources or equipment to perform the task |

| Utilizing resources | ||

| Team level | Supporting team | |

| Supporting line manager | ||

| Organization level | Supportive organizational policy | |

| Involvement of management | ||

| Personal Resources | Psychological capital | Hope |

| Optimism | ||

| Self-efficacy | ||

| Resilience | ||

| Emotional intelligence | Self-awareness | |

| Self-regulation | ||

| Motivation | ||

| Empathy | ||

| Social skills | ||

| Demands | Job level | Prioritizing |

| Reduce stress | ||

| Team level | Better communication | |

| Reduction in conflict | ||

| Organization level | Less resistance for the policy | |

| Follow the policy | ||

| Engagement | Work engagement | See the good outcome from the work |

| Enjoy the work | ||

| Team engagement | Better communication | |

| Collaboration | ||

| Organization engagement | Organization is the giver | |

| Second home | ||

| Enveloping Themes, Sub-Themes, and Sample Quotes | |

| Resources | |

| Enhancement in Perceived Resources | |

| Perceived resources at the job level Awareness of the resources or equipment needed to perform the task: “When working with machines, safety measures such as safety gloves play a crucial role in ensuring my well-being and overall protection.” (Inventory personnel #2) Utilizing resources: “Yes, it is beneficial. Sometimes, things don’t go as planned, right? In the past, I used to react aggressively with my emotions when faced with such challenges. After adopting this mindfulness approach, it’s like giving it another shot with a more positive mindset. Although it might take a bit more time, it often leads to a successful outcome and resolves the issue at hand.” (Sales personnel #5) | |

| Perceived resources at the team level Supportive team: “I find joy in my work, and it’s not stressful. Additionally, I have a positive relationship with my team, including my colleagues and line manager. If any challenges arise, I can consult with my line manager, who provides valuable advice to help us navigate and overcome any issues.” (Production personnel #2) Supportive line manager: “In my opinion, it does to a certain extent. If the tasks assigned by my line manager surpass my current capabilities, I rely on mindfulness. I can seek advice from my supervisor, gradually working on the task while considering their guidance.” (Production personnel #1) | |

| Perceived resources at the organization level Supportive organizational policy: “It provides support. Fostering a positive atmosphere within the organization, coupled with regular meditation or mindfulness practices, often leads to a reduction in errors. Embracing these practices helps me sustain a heightened sense of mindfulness in the workplace.” (Research and marketing planning officer #1) Involvement of management: “The management here is supportive and acts as mentors. The executives are approachable; during meetings, I actively participate by posing questions. If there’s something I don’t understand, I don’t hesitate to raise my hand, and they willingly provide answers and guidance.” (Customer service #1) | |

| Enveloping Themes, Sub-Themes, and Sample Quotes | |

| Personal Resources | |

| Psychological Capital | |

| Hope: “Success is not an individual pursuit. Hoping alone is not enough; it requires a collective effort, a team. Simply fostering personal hopes doesn’t guarantee success. It’s crucial to communicate and share aspirations with others, aligning everyone in the same direction to achieve common goals.” (Sales person #4). | |

| Optimism: “If I maintain an optimistic outlook, it can be beneficial for me. Being optimistic means less stress and not dwelling on negative thoughts. It allows me to avoid unnecessary suffering, letting go of concerns and embracing a positive mindset.” (Sales person #2) | |

| Self-efficacy: “Yes, there is. It’s a belief in my ability. There may have been times when I doubted my capabilities. However, with improved concentration and mindfulness, I’ve realized that it’s not a matter of being unable to do everything. When faced with challenging assignments that initially seem daunting, I’ve learned to be mindful and reframe my thoughts. Instead of succumbing to negativity, I program myself to believe that I can do it. I find that I am capable of accomplishing the task at hand.” (Procurement personnel #1) | |

| Resilience: “Yes, absolutely. Everything I’ve mentioned here serves as a kind of mental toolkit for dealing with challenges. When faced with difficulties, I have specific affirmations or words that help me regain mindfulness more quickly. I recognize that it’s natural for people not to be happy all the time, and having these tools allows me to navigate and overcome moments of adversity.” (Sales person #5) | |

| Enveloping Themes, Sub-Themes, and Sample Quotes | |

| Emotional Intelligence | |

| Self-awareness: “It enhances my approach. For instance, once I understand what I’m currently working on, it allows me to streamline my efforts and work more efficiently.” (Research and marketing planning officer) | |

| Self-regulation: “Managing my mindfulness is crucial. At times, anger tends to take precedence, and in those moments, I may not consider all the reasons behind it. When I’m not mindful, it becomes challenging to pinpoint the true cause, as it may originate from external factors or even within myself.” (Financial officer #1) | |

| Motivation: “I believe that having a clear goal is the key to achieving what I set out to do. It enables me to continually improve myself and stay focused on the target.” (Quality assurance officer #1) | |

| Empathy: “In our work, having a streamlined process is essential. Once we complete a task and ensure its quality through review, the next person in line can seamlessly take over without any concerns. This efficient handover allows them to continue the workflow or proceed with other tasks without the need for additional checks or delays, saving valuable time.” (Diagnostic officer #1) | |

| Social skills: “As mentioned earlier, individuals may experience a range of emotions. Dealing with this requires a strategic approach. I assess their style and preferences, allowing me to tailor my communication and interactions accordingly.” (Production personnel #5) | |

| Enveloping Themes, Sub-Themes, and Sample Quotes | |

| Demands | |

| Perceived demands at the job level Prioritizing: “Indeed, mindfulness is immensely beneficial, especially in prioritizing tasks. Without proper organization, work can become chaotic. Mindfulness enables me to discern the importance of each task, helping me prioritize effectively. By being mindful of what needs immediate attention and what can be deferred.” (Accountant #3) Reduced stress: “Mindfulness leads to better work quality and reduces stress.” (International sales person #1) | |

| Perceived demands at the team level Better communication: “It doesn’t mean I need to counter back. Instead, I choose to be a listener. In challenging situations, it’s crucial to listen first, let them express themselves, and then engage in a conversation once they’ve calmed down. Many times, people who are stressed or facing problems just need someone to listen and understand.” (Production personnel #4) Reduction in conflict: “Well, mindfulness helps me avoid comparing my workload with others. If I approach my work with a positive mindset, being content with what I accomplish, it prevents issues with colleagues and promotes a healthier work environment.” (Maintenance personnel #1) | |

| Perceived demands at the organizational level Less resistance to the policy: “When a policy is implemented, it’s essential for us to adhere to it. Following management guidelines is crucial, as these policies are designed to be beneficial and have undergone careful consideration before being introduced. Complying with policies ensures a smoother and more effective functioning of the organization.” (Inventory personnel #1) Alignment with the policy: “Absolutely, being mindful of the policies is crucial. It’s essential to consider the rationale behind each policy implementation. Policies are typically designed with specific reasons and often support compliance with standards.” (Maintenance personnel #1) | |

| Engagement | Emotional Intelligence | Emerging Themes | Cognitive Flexibility | Emotional Flexibility | Behavioral Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging Themes from the Interviews | Emerging Themes from the Interviews | Emerging Themes from the Interviews | |||

| Work engagement | Self-awareness Self-regulation Motivation | - See the good outcomes from the work | See the good outcomes from the work - Problem-solving, which used to be complicated, has now become more streamlined. I’ve learned the importance of slowing down my thoughts, avoiding rushing, and taking a moment to consider things. This deliberate pace allows for gradual and effective problem resolution, preventing the need for repeated fixes. (Sales person #4) | See the good outcomes from the work - Feeling good about applying and expanding my knowledge is essential, as it contributes significantly to my overall satisfaction and sense of purpose in life. (Engineering manager #1) | See the good outcomes from the work - Processing tasks with focus and consideration significantly improves the quality of the work, minimizing the chances of errors or oversights. (Engineering manager #1) |

| - Enjoy the work | Enjoy the work - After I wake up in the morning, I want to come to work. Maybe it’s just me? I’m not sure. Other people? For the work that I have been assigned, I make the best of it, working like I am on the job for the first day again. (International sales person #1) | Enjoy the work - When I am calm, wisdom will arise. Wisdom is mindfulness. Once there is mindfulness, I am able to do thing happily and experience happiness. Many people can also do the same like me. (Sales person #3) | Enjoy the work - When we have month-end closings, we can complete the task correctly on the first attempt. There’s no need for additional work or wasted time on corrections because I practice mindfulness from the outset. (Accountant #3) | ||

| Team engagement | Empathy Social skills | - Better communication | Better communication - It’s common for people to have varying perspectives, and there might be instances where someone may not share the same opinion or feelings. (Engineering manager #1) - Individuals may experience a range of emotions. Adopting a strategic approach involves considering each person’s unique style and preferences. (Production personnel #5) | Better communication - Maintaining a positive mood enhances my interactions with both colleagues and outsiders. When I’m in a positive state, it is reflected in my conversations and interactions with others. (Research and marketing planning manager #1) | Better communication - Mindfulness plays a crucial role in communication, particularly when acting as the intermediary between the sender and recipient. As a procurement professional, you hold a significant responsibility in conveying the organization’s requirements to suppliers. (Procurement personnel #1) |

| - Collaboration | Collaboration - Diversity in perspectives is inevitable, and it’s common for individuals to hold differing opinions or feelings towards us. Acknowledging and respecting these varying viewpoints is essential for effectively managing interpersonal relationships. (Engineering manager #1) | Collaboration - Through mutual reminders and support, we gradually help each other think and improve. This collaborative effort fosters a positive atmosphere among friends or colleagues, enhancing our sense of camaraderie and mutual assistance. (Accountant #1) | Collaboration - This group mindfulness approach not only promotes individual well-being but also contributes to a reduction in work-related issues and conflicts among colleagues. (Accountant #1) | ||

| Organizational engagement | Self-awareness Self-regulation Motivation | - Organization is the giver | Organization is the giver - It’s a positive aspect of the organization that they provide opportunities for both work and independent thinking. The environment encourages individuals to express their ideas, and constructive criticism is welcomed to refine and improve those ideas. (Sales person #1) | Organization is the giver - I have positive feelings about the organization; it has been beneficial for me. It has played a role in enhancing my interpersonal skills, fostering better communication, and encouraging more thoughtful consideration in my work. (Production personnel #2) | Organization is the giver - I’m content with this workplace. Throughout the year, numerous training sessions are available, both internally and externally. If there’s any interesting external training, offering an open opportunity for continuous learning and skill development without any barriers. (Procurement personnel #1) |

| - Second home | Second home - This place feels like a second home; I come here every day. When I engage in activities, my thoughts connect with my family, considering the organization as a significant part of my daily life. It’s as if this is my second home. (International sales person #1) | Second home - It’s like everything here belongs to me; there’s a sense of ownership. This feeling motivates me to think about ways to improve and advance the business, contributing ideas for the continuous development and progress of our organization. (Accountant #1) | Second home - Your dedication and engagement are noticeable, as you consistently spend more time at work than at home. Beginning work as early as 6:30 or 7:00 am, instead of waiting until 8:30 am, showcases your proactive and committed approach to your responsibilities. (Inventory personnel #1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumprang, K.; Suriyankietkaew, S. Mechanisms of Organizational Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Engagement: A Multi-Level Analysis. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060121

Kumprang K, Suriyankietkaew S. Mechanisms of Organizational Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Engagement: A Multi-Level Analysis. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(6):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060121

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumprang, Kriengkrai, and Suparak Suriyankietkaew. 2024. "Mechanisms of Organizational Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Engagement: A Multi-Level Analysis" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 6: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060121

APA StyleKumprang, K., & Suriyankietkaew, S. (2024). Mechanisms of Organizational Mindfulness on Employee Well-Being and Engagement: A Multi-Level Analysis. Administrative Sciences, 14(6), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060121