Exploring Shared Challenges of Empowered Patients and Entrepreneurs: Towards Diversity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Post-Crisis Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What shared challenges do chronic patients and entrepreneurs encounter, and how are these challenges addressed to empower them?

- What are the fundamental mechanisms contributing to the empowerment of patients and entrepreneurs, and how do these mechanisms intersect within their communities?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Entrepreneurship Background

2.2. Empowerment Foundations

2.2.1. Self-Efficacy

2.2.2. Social Support

2.2.3. Collaboration and Cooperation

2.2.4. Education

2.3. Empowerment Factors

2.3.1. Autonomy and Self-Determination

2.3.2. Active Participation and Engagement

2.3.3. Collective Action

2.3.4. Opportunities and Innovation

2.4. Empowerment in Personal Health Management and Entrepreneurship

2.5. Empowerment through Human Capital and Intellectual Capital

2.6. Empowerment Through Knowledge-Based Drivers for Diversity and Innovation

3. Methods

3.1. Literature Review

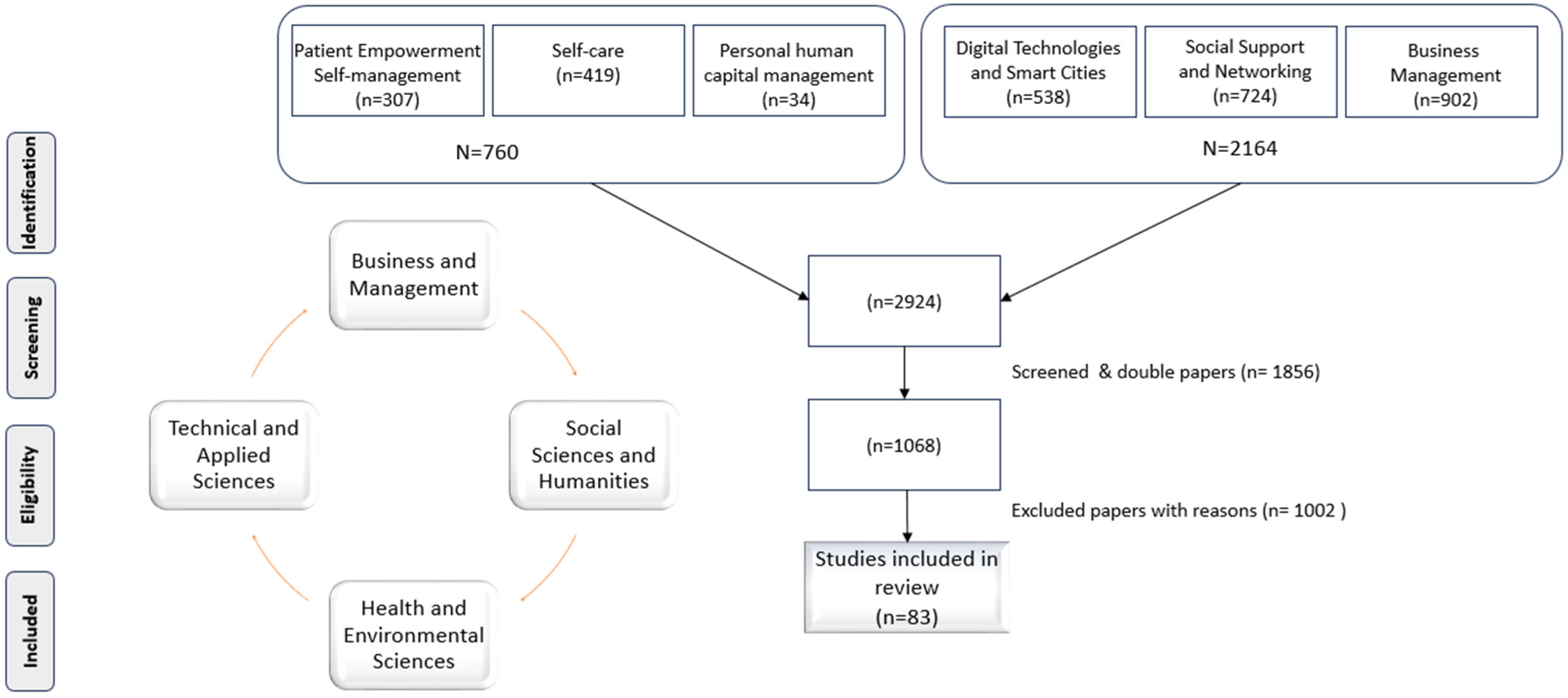

3.1.1. Scoping Literature Review

- Methodology Designs: Excluded research articles primarily focused on methodological approaches, study designs, or methodological critiques.

- Clinical Skills and Healthcare Interventions: Excluded studies that primarily focused on clinical skills training, medical procedures, or specific healthcare interventions unless they directly addressed empowerment in PHM or entrepreneurship.

- Environmental Issues: Excluded studies primarily focused on environmental conservation, climate change, or ecological sustainability unless they explicitly discussed their impact on empowerment in healthcare or entrepreneurship contexts.

- Technological Advancements: Excluded studies solely focused on technological innovations or advancements in healthcare or entrepreneurship unless they specifically addressed their role in empowering individuals or communities.

- Socioeconomic Aspects: Excluded studies primarily focused on socioeconomic factors such as poverty, inequality, or economic development unless they were directly related to empowerment in PHM or entrepreneurship.

3.1.2. Transdisciplinary Research (TDR)

3.1.3. Methodological Rigor

3.2. Qualitative Study

3.2.1. Study Setting and Participants

3.2.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Empowerment Experiences and Shared Challenges

4.2. Contributions of Empowerment to Economic Progress

4.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

4.4. Qualitative Analysis: Insights from Virtual Patient Communities

- BA Support Group

- Description: The BA support group emphasized health, well-being, and information exchange, promoting knowledge sharing and mutual support for health-related matters.

- VCBA Support Group

- Description: The VCBA support group focused on group dynamics, providing support, faith, and discussions related to health and emotional well-being.

- Empowerment Through Effective Information:

- Description: Effective information played a pivotal role in shaping empowerment dynamics within online support groups.

- Empowerment Manifestation: Access to relevant information enhances health literacy and decision-making capabilities, enabling informed choices and healthy lifestyle habits. The thematic analysis underscored the importance of “Effective information” in empowering individuals within virtual communities.

5. Theoretical Framework

5.1. Empowerment Foundations and Factors

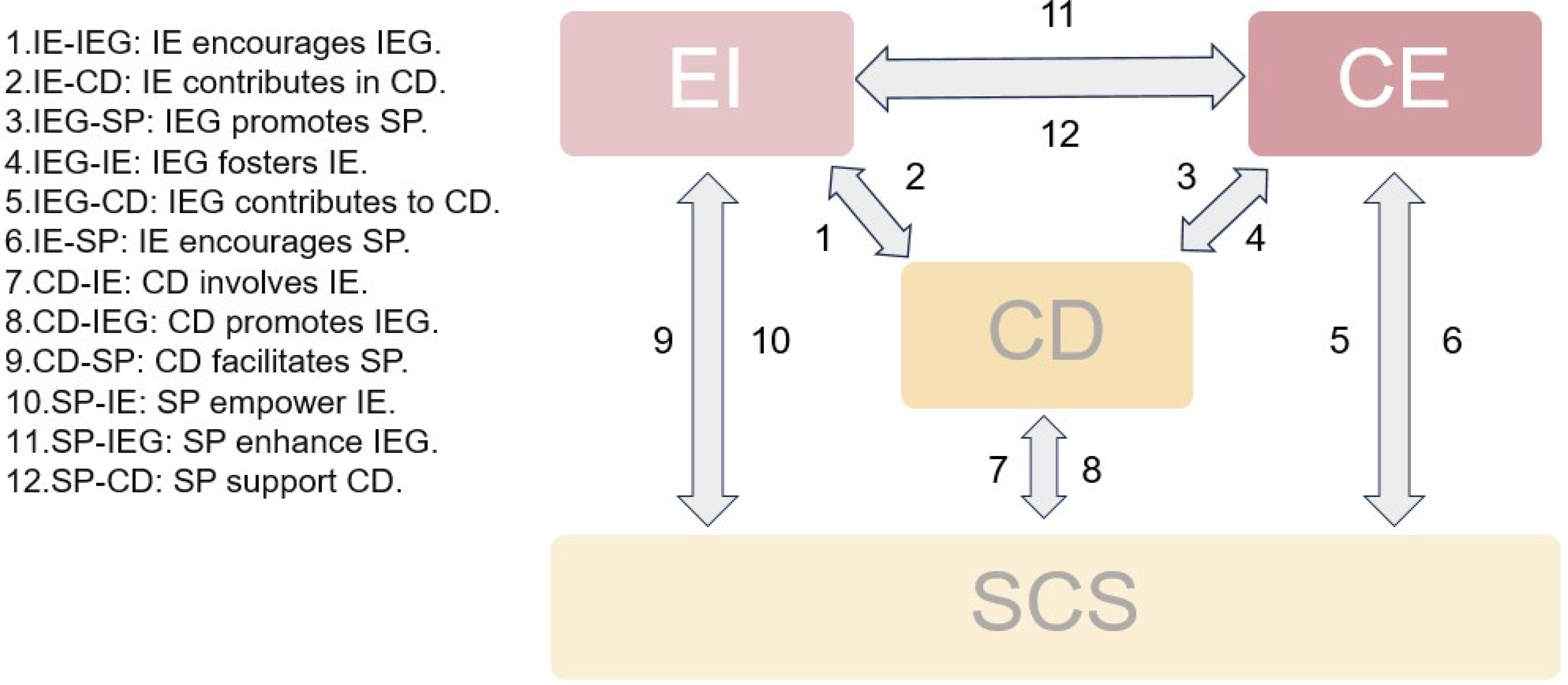

5.2. Core Components and Stages

- Individual Empowerment (IE): This stage focuses on empowering individuals, enhancing their capabilities, and fostering a sense of autonomy and control over their lives.

- Individual Engagement (IEG): After individuals are empowered, they become actively engaged in various activities within their communities. This stage involves participation, contribution, and involvement in community initiatives and projects.

- Community Development (CD): As individuals engage and collaborate with one another, the community as a whole undergoes development. This stage involves collective efforts aimed at improving the well-being, infrastructure, and overall quality of life within the community.

- Sustainable Practices (SP): Finally, sustainable practices are implemented to ensure that the development achieved is sustainable in the long term. This stage involves adopting practices that promote environmental sustainability, social equity, and economic stability within the community.

5.2.1. Individual Empowerment

- IE-IEG: Individual empowerment encourages individual engagement by instilling individuals with the confidence and resilience necessary to actively participate and engage meaningfully in their communities or organizations.

- IE-CD: Individual empowerment contributes to community development by empowering individuals to actively participate in collaborative efforts and collective action aimed at enhancing community well-being and development.

- IE-SP: Individual empowerment promotes sustainable practices by empowering individuals to advocate for and adopt sustainable behaviors, contributing to environmental, social, and economic sustainability.

5.2.2. Individual Engagement

- IEG-IE: Individual engagement fosters individual empowerment by providing opportunities for individuals to assert control over their lives and make informed decisions, thereby enhancing their sense of autonomy and self-determination.

- IEG-CD: Individual engagement contributes to community development by mobilizing individuals to collaborate and cooperate, thereby driving collective progress and addressing common challenges within communities.

- IEG-SP: Individual engagement encourages sustainable practices by promoting active involvement in initiatives that promote environmental, social, and economic sustainability.

5.2.3. Community Development

- CD-IE: Community development involves individual empowerment by providing opportunities for individuals to assert their autonomy and contribute to the collective progress and resilience of their communities.

- CD-IEG: community development promotes individual engagement by creating environments conducive to active participation and fostering a sense of belonging and commitment among community members.

- CD-SP: community development facilitates sustainable practices by establishing frameworks for collaborative action and collective problem-solving, which in turn promotes the adoption of environmentally friendly technologies and methods within communities.

5.2.4. Sustainable Practices

- SP-IE: Sustainable practices enhance individual empowerment by providing opportunities for personal growth and success through the adoption of sustainable behaviors and initiatives.

- SP-IEG: Sustainable practices enhance individual engagement by providing meaningful opportunities for individuals to engage in activities that contribute to the well-being and sustainability of their communities.

- SP-CD: Sustainable practices support community development by promoting initiatives that enhance community resilience, social cohesion, and well-being, ultimately fostering long-term community development.

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Understanding Empowerment Dynamics and Implications

6.2. Synthesis of Findings

6.3. Utilization of Virtual Communities for Diversity and Innovation

- Diverse Participants: Virtual communities attract a diverse range of individuals managing chronic health conditions and involved in entrepreneurship, enhancing research diversity.

- Innovation Hubs: Virtual communities foster creativity and innovation, enabling researchers to identify novel solutions through interactions and collaborations.

- Intersectionality Exploration: Researchers can analyze how factors like gender, race, and socioeconomic status intersect within virtual communities, informing inclusive approaches.

- Inclusive Empowerment Strategies: Engaging with community members allows researchers to co-create culturally sensitive interventions, ensuring they meet diverse needs.

- Cross-disciplinary Collaboration: Virtual platforms bring together individuals with diverse expertise, fostering collaborative problem-solving and innovative ideas.

- Cultural Competence: Researchers adopt culturally sensitive communication strategies, building trust and rapport with community members from diverse backgrounds.

- Promotion of Inclusive Entrepreneurship: Virtual communities support underrepresented groups in entrepreneurship, enabling researchers to develop initiatives that address barriers and promote diversity.

6.4. Theoretical Implications

6.5. Practical Implications

6.6. Implications for Intellectual Capital and Sustainable Development

6.7. Fostering Innovation, Collaborative Networks, and Inclusive Development

6.8. Addressing Potential Drawbacks of Empowerment Initiatives

7. Conclusions

7.1. Limitations

7.2. Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acs, Zoltan J., and Fiona Sussan. 2017. The Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Small Business Economics 49: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Mora, Mariela, Carina Sparud-Lundin, Philip Moons, and Ewa Lena Bratt. 2022. Definitions, Instruments and Correlates of Patient Empowerment: A Descriptive Review. Patient Education and Counseling 105: 346–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, Paul S., and Seok-Woo Kwon. 2002. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Academy of Management Review 27: 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, Teresa M. 2018. Creativity in Context: Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Robert M., and Martha M. Funnell. 2010. Patient Empowerment: Myths and Misconceptions. Patient Education and Counseling 79: 277–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, David B., and Erik Lehmann. 2006. Entrepreneurial Access and Absorption of Knowledge Spillovers: Strategic Board and Managerial Composition for Competitive Advantage. Journal of Small Business Management 44: 155–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aujoulat, Isabelle, William d’Hoore, and Alain Deccache. 2007. Patient Empowerment in Theory and Practice: Polysemy or Cacophony? Patient Education and Counseling 66: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacq, Sophie, Christina Hertel, and G. T. Lumpkin. 2022. Communities at the Nexus of Entrepreneurship and Societal Impact: A Cross-Disciplinary Literature Review. Journal of Business Venturing 37: 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcazar, Fabricio E., JoAnn Kuchak, Shawn Dimpfl, Varun Sariepella, and Francisco Alvarado. 2014. An Empowerment Model of Entrepreneurship for People with Disabilities in the United States. Psychosocial Intervention 23: 145–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2001. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Isaac, Adam Steventon, Robert Williamson, and Sarah R. Deeny. 2018. Self-Management Capability in Patients with Long-Term Conditions Is Associated with Reduced Healthcare Utilisation across a Whole Health Economy: Cross-Sectional Analysis of Electronic Health Records. BMJ Quality & Safety 27: 989–99. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Gary S. 1964. Human Capital A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belitski, Maksim, and Keith Heron. 2017. Expanding Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystems. Journal of Management Development 36: 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, Maksim, Rosa Caiazza, and Erik E. Lehmann. 2021. Knowledge Frontiers and Boundaries in Entrepreneurship Research. Small Business Economics 56: 521–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaique, Lama, Hussein Nabil Ismail, and Hazem Aldabbas. 2023. Organizational Learning, Resilience and Psychological Empowerment as Antecedents of Work Engagement during COVID-19. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 72: 1584–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, Rachel, Christian Le Bas, Caroline Mothe, and Nicolas Poussing. 2019. Strategic CSR for Innovation in SMEs: Does Diversity Matter? Long Range Planning 52: 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolisani, Ettore, and Constantin Bratianu. 2017. Knowledge Strategy Planning: An Integrated Approach to Manage Uncertainty, Turbulence, and Dynamics. Journal of Knowledge Management 21: 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzakhem, Najib, Panteha Farmanesh, Pouya Zargar, Muhieddine Ramadan, Hala Baydoun, Amira Daouk, and Ali Mouazen. 2023. Rebuilding the Workplace in the Post-Pandemic Age through Human Capital Development Programs: A Moderated Mediation Model. Administrative Sciences 13: 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, Constantin, and Ruxandra Bejinaru. 2020. Knowledge Dynamics: A Thermodynamics Approach. Kybernetes 49: 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, Paulina, Adrian Edwards, Paul James Barr, Isabelle Scholl, Glyn Elwyn, and Marion McAllister. 2015. Conceptualising Patient Empowerment: A Mixed Methods Study. BMC Health Services Research 15: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajaiba-Santana, Giovany. 2014. Social Innovation: Moving the Field Forward. A Conceptual Framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 82: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, Elias G., David F. J. Campbell, and Evangelos Grigoroudis. 2022. Helix Trilogy: The Triple, Quadruple, and Quintuple Innovation Helices from a Theory, Policy, and Practice Set of Perspectives. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 13: 2272–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2000. Toward a Sociology of the Network Society. Contemporary Sociology 29: 693–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Eva Marie, Tine Van Regenmortel, Kris Vanhaecht, Walter Sermeus, and Ann Van Hecke. 2016. Patient Empowerment, Patient Participation and Patient-Centeredness in Hospital Care: A Concept Analysis Based on a Literature Review. Patient Education and Counseling 99: 1923–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champenois, Claire, Vincent Lefebvre, and Sébastien Ronteau. 2020. Entrepreneurship as Practice: Systematic Literature Review of a Nascent Field. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 32: 281–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chandna, Vallari, and Manjula S. Salimath. 2020. When Technology Shapes Community in the Cultural and Craft Industries: Understanding Virtual Entrepreneurship in Online Ecosystems. Technovation 92: 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Chun Wei, and Nick Bontis. 2002. The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Sheldon, and Thomas Ashby Wills. 1985. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 98: 310–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S. 2009. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. In Knowledge and Social Capital. London: Routledge, pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- De Bem Machado, Andreia, Silvana Secinaro, Davide Calandra, and Federico Lanzalonga. 2022. Knowledge Management and Digital Transformation for Industry 4.0: A Structured Literature Review. Knowledge Management Research & Practice 20: 320–38. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, Ed. 2012. New Findings and Future Directions for Subjective Well-Being Research. American Psychologist 67: 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, Robert. 1976. Theory Building in Applied Areas. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 17: 39. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, Robert. 1978. Theory Development. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, Angela L., Christopher Peterson, Michael D. Matthews, and Dennis R Kelly. 2007. Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, Carol S. 2006. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, Jeffrey H., and Kentaro Nobeoka. 2000. Creating and Managing a High-performance Knowledge-sharing Network: The Toyota Case. Strategic Management Journal 21: 345–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, Leif, and Patrick Sullivan. 1996. Developing a Model for Managing Intellectual Capital. European Management Journal 14: 356–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Jeffrey A. Martin. 2000. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strategic Management Journal 21: 1105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, Anim, Imam Syairozi, and Lailatur Rohimah. 2021. Youth Creative Entrepreneur Empowerment (YOUTIVEE): Solutions for Youth to Contribute to the Economy and Reduce Unemployment. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research (IJEBAR) 5: 1689–97. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Jeana, and Michael Massagli. 2008. Social Uses of Personal Health Information within PatientsLikeMe, an Online Patient Community: What Can Happen When Patients Have Access to One Another’s Data. Journal of Medical Internet Research 10: e1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, Lia Paola, Giovanni Radaelli, Emanuele Lettieri, and Cristina Masella. 2015. Patient Empowerment and Its Neighbours: Clarifying the Boundaries and Their Mutual Relationships. Health Policy 119: 384–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallant, Mary P. 2003. The Influence of Social Support on Chronic Illness Self-Management: A Review and Directions for Research. Health Education & Behavior 30: 170–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gratton, Lynda, and Sumantra Ghoshal. 2003. Managing Personal Human Capital: New Ethos for the ‘Volunteer’Employee. European Management Journal 21: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurău, Călin, and Léo Paul Dana. 2018. Environmentally-Driven Community Entrepreneurship: Mapping the Link between Natural Environment, Local Community and Entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 129: 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Stuart L., and Mark B. Milstein. 2003. Creating Sustainable Value. Academy of Management Perspectives 17: 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzler, Andrea, and Wanda Pratt. 2011. Managing the Personal Side of Health: How Patient Expertise Differs from the Expertise of Clinicians. Journal of Medical Internet Research 13: e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, Nile W., and Jeffrey H. Dyer. 2004. Human Capital and Learning as a Source of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management Journal 25: 1155–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, Christine A. 2005. Personal Values as a Catalyst for Corporate Social Entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics 60: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Zapata, Daniel, and José M. Peiró. 2018. The Importance of Empowerment in Entrepreneurship. In Inside the Mind of the Entrepreneur: Cognition, Personality Traits, Intention, and Gender Behavior. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, Judith, and Jessica Greene. 2013. What the Evidence Shows about Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes and Care Experiences; Fewer Data on Costs. Health Affairs 32: 207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Timothy B. Smith, and J. Bradley Layton. 2010. Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review. Edited by Carol Brayne. PLoS Medicine 7: e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, Jacqueline N., and John E. Young. 1993. Entrepreneurship’s Requisite Areas of Development: A Survey of Top Executives in Successful Entrepreneurial Firms. Journal of Business Venturing 8: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Hsiu Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Shih-Wei, and Peter Lamb. 2020. Still in Search of Learning Organization? Towards a Radical Account of The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. The Learning Organization 27: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado Illanes, Marisol. 2019. Inclusiveness in Healthcare: Knowledge Ecosystems Innovation in Oncology and Chronic Disease. In European Conference on Knowledge Management. Reading: Academic Conferences International Limited, pp. 1182–92. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, Barbara A., Barry Checkoway, Amy Schulz, and Marc Zimmerman. 1994. Health Education and Community Empowerment: Conceptualizing and Measuring Perceptions of Individual, Organizational, and Community Control. Health Education Quarterly 21: 149–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius Onakoya, Adebiyi, and Adegbemi Babatunde. 2013. Entrepreneurship, Economic Development and Inclusive Growth. International Journal of Social Sciences and Entrepreneurship 1: 375–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, Stefan, and Rod B. McNaughton. 2018. Resilience and Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 24: 1129–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, David P. M., Maria E. Freund, Josefa Kny, Oskar Marg, Melanie Mbah, Lena Theiler, Matthias Bergmann, Bettina Brohmann, Daniel J. Lang, and Martina Schäfer. 2021. Transdisciplinary Research: Towards an Integrative Perspective. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 30: 243–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K O’brien. 2010. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implementation Science 5: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, Eric, and Christoph Winkler. 2020. From Offline to Online: Challenges and Opportunities for Entrepreneurship Education Following the COVID-19 Pandemic. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy 3: 346–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, Kate R., and Halsted R. Holman. 2003. Self-Management Education: History, Definition, Outcomes, and Mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 26: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Carolyn M. Youssef-Morgan. 2017. Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 4: 339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Elina S. Ibrayeva. 2006. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy in Central Asian Transition Economies: Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses. Journal of International Business Studies 37: 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, Suniya S. 2015. Resilience in Development: A Synthesis of Research across Five Decades. In Developmental Psychopathology: Volume Three: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 739–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Colin, and Ross Brown. 2014. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD, Paris 30: 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, M. Travis, Lucy L. Gilson, and John E. Mathieu. 2012. Empowerment—Fad or Fab? A Multilevel Review of the Past Two Decades of Research. Journal of Management 38: 1231–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, Kate K., Sejin Paik, Briana Trifiro, and James E. Katz. 2023. Coping during COVID-19: How Attitudinal, Efficacy, and Personality Differences Drive Adherence to Protective Measures. Journal of Communication in Healthcare 17: 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, Marion, Graham Dunn, Katherine Payne, Linda Davies, and Chris Todd. 2012. Patient Empowerment: The Need to Consider It as a Measurable Patient-Reported Outcome for Chronic Conditions. BMC Health Services Research 12: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, Sachin A., and A. M. Rawani. 2019. Understanding Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD) 10: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Yi, and Carolyn A. Lin. 2017. The Impact of Online Social Capital on Social Trust and Risk Perception. Asian Journal of Communication 27: 563–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Pablo, and Boyd Cohen. 2018. Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead. Business Strategy and the Environment 27: 300–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, Janine, and Sumantra Ghoshal. 2009. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. In Knowledge and Social Capital. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis Inc, pp. 119–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, Satish. 2017. Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 41: 1029–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, Satish, and Robert A. Baron. 2013. Entrepreneurship in Innovation Ecosystems: Entrepreneurs’ Self-Regulatory Processes and Their Implications for New Venture Success. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37: 1071–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolopoulou, Katerina, Mine Karataş-Özkan, Frank Janssen, and John M. Jermier. 2017. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group Earthscan from Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, Branda, and Neil M. Boyd. 2014. Sense of Community Responsibility in Community Collaboratives: Advancing a Theory of Community as Resource and Responsibility. American Journal of Community Psychology 54: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okojie, Glory, Ida Rosnita Ismail, Halima Begum, A. S. A. Ferdous Alam, and Elkhan Richard Sadik-Zada. 2023. The Mediating Role of Social Support on the Relationship between Employee Resilience and Employee Engagement. Sustainability 15: 7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagioti, Maria, Gerry Richardson, Nicola Small, Elizabeth Murray, Anne Rogers, Anne Kennedy, Stanton Newman, and Peter Bower. 2014. Self-Management Support Interventions to Reduce Health Care Utilisation without Compromising Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Health Services Research 14: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Douglas D., and Marc A. Zimmerman. 1995. Empowerment Theory, Research, and Application. American Journal of Community Psychology 23: 569–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah D. J., Christina M. Godfrey, Hanan Khalil, Patricia McInerney, Deborah Parker, and Cassia Baldini Soares. 2015. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 141–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigg, Kenneth E. 2002. Three Faces of Empowerment: Expanding the Theory of Empowerment in Community Development. Community Development 33: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ramoglou, Stratos, William B. Gartner, and Eric W. K. Tsang. 2020. “Who Is an Entrepreneur?’ Is (Still) the Wrong Question. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 13: e00168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, Julian. 1995. Empowerment Meets Narrative: Listening to Stories and Creating Settings. American Journal of Community Psychology 23: 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Lubna. 2019. Entrepreneurship Education and Sustainable Development Goals: A Literature Review and a Closer Look at Fragile States and Technology-Enabled Approaches. Sustainability 11: 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridings, Catherine M., and David Gefen. 2004. Virtual Community Attraction: Why People Hang out Online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10: JCMC10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissel, Christopher. 1994. Empowerment: The Holy Grail of Health Promotion? Health Promotion International 9: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. 2015. The Age of Sustainable Development. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi, Negin. 2022. How Does the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Contribute to the Performance of Entrepreneurial Start-Up Firms? In Advances in Best-Worst Method: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Best-Worst Method (BWM2021). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bayón, Antonio, Esther González-Arnedo, and Ángel Andreu-Escario. 2022. Spanish Healthcare Sector Management in the COVID-19 Crisis under the Perspective of Austrian Economics and New-Institutional Economics. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 801525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Bayón, Antonio, F. Javier Sastre, and Luis Isasi Sánchez. 2024. Public Management of Digitalization into the Spanish Tourism Services: A Heterodox Analysis. Review of Managerial Science 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, Theodore W. 1961. Investment in Human Capital. The American Economic Review 51: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A., and Richard Swedberg. 2021. The Theory of Economic Development. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 2017. Well-Being, Agency and Freedom the Dewey Lectures 1984. In Justice and the Capabilities Approach. London: Routledge, pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, Scott, and Sankaran Venkataraman. 2000. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Academy of Management Review 25: 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, Scott Andrew. 2003. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, Dean A., and Holger Patzelt. 2011. The New Field of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Studying Entrepreneurial Action Linking ‘What Is to Be Sustained’ with ‘What Is to Be Developed’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindakis, Stavros, and Fotis Kitsios. 2016. Entrepreneurial Dynamics and Patient Involvement in Service Innovation: Developing a Model to Promote Growth and Sustainability in Mental Health Care. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 7: 545–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaridis, Ioannis, and Fotis Kitsios. 2024. Digital Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurship Education: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 30: 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Nicola, Peter Bower, Carolyn A. Chew-Graham, Diane Whalley, and Joanne Protheroe. 2013. Patient Empowerment in Long-Term Conditions: Development and Preliminary Testing of a New Measure. BMC Health Services Research 13: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithson, Rachael, Elisha Roche, and Christina Wicker. 2021. Virtual Models of Chronic Disease Management: Lessons from the Experiences of Virtual Care during the COVID-19 Response. Australian Health Review 45: 311–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, Charles C., Dorthe Døjbak Håkonsson, and Børge Obel. 2017. A Smart City Is a Collaborative Community. California Management Review 59: 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, David, David Pauleen, and Sally Jansen van Vuuren. 2016. Managing Your Own Knowledge: A Personal Perspective. In Personal Knowledge Management: Individual, Organizational and Social Perspectives. Edited by G. E. Gorman. London: Routledge, pp. 121–36. [Google Scholar]

- Spigel, Ben. 2017. The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41: 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, Erik. 2015. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique. European Planning Studies 23: 1759–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Thomas A. 2007. The Wealth of Knowledge: Intellectual Capital and the Twenty-First Century Organization. Melbourne: Crown Currency. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, Michael. 2005. Society, Community, and Economic Development. Studies in Comparative International Development 39: 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Tanya Ya, Gregory J. Fisher, and William J. Qualls. 2021. The Effects of Inbound Open Innovation, Outbound Open Innovation, and Team Role Diversity on Open Source Software Project Performance. Industrial Marketing Management 94: 216–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, David J., Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen. 1997. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal 18: 509–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, Christina, Karim Messeghem, and Mark P. Rice. 2018. A Social Capital Approach to the Development of Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: An Explorative Study. Small Business Economics 51: 153–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, Peggy A. 2011. Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52: 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, Tuukka. 2016. What Is the Social Innovation Community? Conceptualizing an Emergent Collaborative Organization. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 7: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, Jens M., Andreas Rauch, Michael Frese, and Nina Rosenbusch. 2011. Human Capital and Entrepreneurial Success: A Meta-Analytical Review. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 341–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainauskienė, Vestina, and Rimgailė Vaitkienė. 2021. Enablers of Patient Knowledge Empowerment for Self-Management of Chronic Disease: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma Martí, José María, and Maria do Rosário Cabrita. 2012. Entrepreneurial Excellence in the Knowledge Economy: Intellectual Capital Benchmarking Systems. Palgrave Macmillan. Available online: https://books.google.es/books/about/Entrepreneurial_Excellence_in_the_Knowle.html?id=ckayDNucIE0C&redir_esc=y (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Viedma Martí, José María, and Maria do Rosário Cabrita. 2023. Advancing the Intellectual Capital Theory: Some Ways Forward. In ECKM 2023 24th European Conference on Knowledge Management. Reading: Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Von Krogh, Georg, Ikujiro Nonaka, and Lise Rechsteiner. 2012. Leadership in Organizational Knowledge Creation: A Review and Framework. Journal of Management Studies 49: 240–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadichar, Rahul Krushnaji, Prashant Manusmare, and Mukul Abasaheb Burghate. 2024. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: A Systematic Literature Review. Vision 28: 143–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Casey A., and Morhaf. Al Achkar. 2021. A Qualitative Study of Online Support Communities for Lung Cancer Survivors on Targeted Therapies. Supportive Care in Cancer 29: 4493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Sascha G., and Simon Heinrichs. 2015. Who Becomes an Entrepreneur? A 30-Years-Review of Individual-Level Research. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 22: 225–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Etienne. 2010. Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept. In Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. London: Springer, pp. 179–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, Etienne, Richard McDermott, and William M. Snyder. 2002. Seven Principles for Cultivating Communities of Practice. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge 4: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, Matthias, Sarah Stanske, and Marvin B. Lieberman. 2020. Strategic Responses to Crisis. Strategic Management Journal 41: 3161. [Google Scholar]

- Wigger, Karin Andrea, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2020. We’re All in the Same Boat: A Collective Model of Preserving and Accessing Nature-Based Opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44: 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Chris. K., Julian Thomas, and Jo Barraket. 2019. Measuring digital inequality in Australia: The Australian digital inclusion index. Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy 7: 102–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Bronwyn P., Poh Yen Ng, and Bettina Lynda Bastian. 2021. Hegemonic Conceptualizations of Empowerment in Entrepreneurship and Their Suitability for Collective Contexts. Administrative Sciences 11: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, Hasnain, Yvonne Breyer, and John Dumay. 2019. Digital Entrepreneurship: An Interdisciplinary Structured Literature Review and Research Agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 148: 119735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., and Mike Wright. 2016. Understanding the Social Role of Entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies 53: 610–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zautra, Alex J., Anne Arewasikporn, and Mary C. Davis. 2010. Resilience: Promoting Well-Being through Recovery, Sustainability, and Growth. Research in Human Development 7: 221–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shaodian, Erin O’ Carrol Bantum, Jason Owen, Suzanne Bakken, and Noémie Elhadad. 2017. Online Cancer Communities as Informatics Intervention for Social Support: Conceptualization, Characterization, and Impact. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 24: 451–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Zhe. 2019. Sustained Participation in Virtual Communities from a Self-Determination Perspective. Sustainability 11: 6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Yingqin, and Geoff Walsham. 2008. Inequality of What? Social Exclusion in the E-society as Capability Deprivation. Information Technology & People 21: 222–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, Marc A. 1995. Psychological Empowerment: Issues and Illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology 23: 581–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Key Themes | Relevant Theories, Models, and Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Empowerment | Self-efficacy, autonomy and self-determination | (Bandura 1997; Maynard et al. 2012) |

| Community Support and Engagement | Social support, active participation and engagement | (Cohen and Wills 1985; Nahapiet and Ghoshal 2009) |

| Human and Intellectual Capital | Collaboration and cooperation, collective action, knowledge-based drivers and dynamics | (Becker 1964; Gratton and Ghoshal 2003) |

| Sustainable Practices | Sustainable practices, opportunities, and innovation | (Putnam 2000; Shepherd and Patzelt 2011) |

| Perspective | Focus | Key Findings | Relevant Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| EE | Role of Empowerment in Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurship fosters personal growth and empowerment. | (Bacq et al. 2022; Balcazar et al. 2014; Henao-Zapata and Peiró 2018) |

| EPH | Role of Empowerment in PHM | Empowered patients take active roles in health decisions. | (Acuña Mora et al. 2022; Anderson and Funnell 2010; Castro et al. 2016; Lorig and Holman 2003) |

| Similarities | Commonalities between Entrepreneurs and Empowered Patients | Both involve individuals taking control of decisions, leading to personal growth and autonomy. | (Bandura 1997; Bandura 2001; Sen 2017; Ryan and Deci 2000) |

| Perspective | Focus | Key Findings | Relevant Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPH | Role of Empowerment in Health Decision-Making | Empowered patients contribute to the overall efficiency and effectiveness of health management. | (Acuña Mora et al. 2022; Anderson and Funnell 2010; Castro et al. 2016; Lorig and Holman 2003) |

| EE | Role of Entrepreneurship in Economic Development | Entrepreneurship significantly contributes to growth and development. | (Bacq et al. 2022; Hart and Milstein 2003; Nambisan 2017; Zahra and Wright 2016) |

| Commonalities | Similarities between Empowered Patients and Entrepreneurs | Individual-driven innovation ecosystems emphasize the transformative potential of empowered individuals in shaping the future of service delivery and driving positive outcomes for individuals and society as a whole. | (Barker et al. 2018; Nambisan and Baron 2013; Cajaiba-Santana 2014; Shane 2003) |

| HCED | Contributions to Economic Progress | Empowered patients ultimately contribute to the healthcare system’s efficiency and contribute to sustainable economic growth through improved health outcomes. Entrepreneurs drive economic growth by fostering innovation, job creation, and competitiveness. | (Acuña Mora et al. 2022; Anderson and Funnell 2010; Hart and Milstein 2003; Panagioti et al. 2014) |

| Perspective | Human Capital and Personal Growth (EPG) | Intellectual Capital and Community Development (ICED) |

|---|---|---|

| Empowerment | Individuals gaining control over their lives and circumstances (Zimmerman 1995) | Empowering individuals within the community (Perkins and Zimmerman 1995) |

| Skills and competences | Skills, knowledge, and abilities of individuals (Becker 1964) | Tangible and intangible assets contributing to intellectual wealth (Stewart 2007) |

| Dynamic learning capability | Adaptability and capacity for acquiring new knowledge and skills (Dweck 2006) | Processes facilitating knowledge creation and utilization (Teece et al. 1997) |

| Self-efficacy | Beliefs in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations (Bandura 1997) | Confidence in one’s capacity to contribute effectively (Bandura 2001; Mou and Lin 2017) |

| Psychological constructs | Factors contributing to well-being and quality of life (Diener 2012) | Collective well-being and resilience factors (Putnam 2000) |

| Collaboration | Working together towards common goals (Wenger 2010 ) | Cooperative efforts for community advancement (Wenger et al. 2002) |

| Active community engagement | Involvement and participation in community initiatives (Small et al. 2013; Zhang 2019) | Participation in community decision-making processes (Snow et al. 2017; Zhang 2019) |

| Inclusive development | Ensuring equal opportunities for all community members (Sen 2017) | Ensuring participation and benefits for all members (Nowell and Boyd 2014) |

| Sustainable development | Promoting economic, social, and environmental progress (Sachs 2015) | Balanced progress supporting long-term well-being (Shepherd and Patzelt 2011; Zautra et al. 2010) |

| Blog Support | Virtual Community and Blog Support | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| information | 16.00 | group (community) | 17.27% |

| health | 14.00 | faith/God | 7.55% |

| diet | 12.00 | support | 4.32% |

| treatment | 10.00 | Advice | 3.24% |

| food | 7.00 | Food | 2.52% |

| blog | 5.00 | Diet | 2.16% |

| advice | 4.00 | Illness | 2.52% |

| care | 4.00 | treatment | 2.16% |

| pain | 4.00 | Health | 2.16% |

| situation | 4.00 | Care | 1.80% |

| therapy | 4.00 | strength | 1.80% |

| time | 4.00 | healing | 1.44% |

| body | 3.00 | recovery | 1.44% |

| condition | 3.00 | challenge | 1.08% |

| habit | 3.00 | depression | 1.08% |

| help | 3.00 | Pain | 1.08% |

| life | 3.00 | Change | 0.72% |

| nutrition | 3.00 | Habit | 0.72% |

| support | 2.00 | Hope | 0.72% |

| Empowerment Foundations | Empowerment Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy | Autonomy and Self-Determination | ||

| Personal control | 6% | Acceptance, adaptability | 6% |

| Decision making | 3% | Strong sense of purpose | 1% |

| Positive attitude | 6% | Spiritual beliefs | 4% |

| Personal traits | 4% | Active Participation and Engagement | |

| Psychological strength | 5% | Lurking | 6% |

| Resilience | 3% | Emotional engagement | 4% |

| Social Support: | Collective Action | ||

| Relational support | 2% | Social impact | 5% |

| Strong social support | 7% | Psychological impact | 7% |

| Collaboration and Cooperation | Physical and intellectual impact | 8% | |

| Enabling others | 6% | Opportunities and Innovation | |

| Empowerment Group | 3% | Healthy lifestyle | 5% |

| Education | |||

| Access to information | 4% | ||

| Health literacy | 2% | ||

| Effective information | 10% | ||

| Process | Foundation | Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Empowerment (IE) | Self-efficacy | Autonomy and self-determination |

| Individual Engagement (IEG) | Social Support | Active Participation and Engagement |

| Community Development (CD) | Collaboration and cooperation | Collective Action |

| Sustainable Practices (SP) | Education | Opportunities and innovation |

| Overall stages | Resource management | Access to resources |

| Overall stages | Information | Knowledge and understanding |

| Stage | Interrelated SDGs |

|---|---|

| Individual Empowerment (IE) | SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 4 (Quality Education) |

| Individual Engagement (IEG) | SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) |

| Community Development (CD) | SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) |

| Sustainable Practices (SP) | SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 15 (Life on Land) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hurtado Illanes, M. Exploring Shared Challenges of Empowered Patients and Entrepreneurs: Towards Diversity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Post-Crisis Contexts. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080164

Hurtado Illanes M. Exploring Shared Challenges of Empowered Patients and Entrepreneurs: Towards Diversity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Post-Crisis Contexts. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(8):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080164

Chicago/Turabian StyleHurtado Illanes, Marisol. 2024. "Exploring Shared Challenges of Empowered Patients and Entrepreneurs: Towards Diversity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Post-Crisis Contexts" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 8: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080164

APA StyleHurtado Illanes, M. (2024). Exploring Shared Challenges of Empowered Patients and Entrepreneurs: Towards Diversity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Post-Crisis Contexts. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080164