Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination at Work: Gender Stereotypes and Overtime—An Exploratory Study in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. A Previous Study and an Exploratory Survey Carried Out in 2021

2.2. A Desk Review in Portugal

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adăscăliței, Dragos, Jason Heyes, and Pedro Mendonça. 2022. The intensification of work in Europe: A multilevel analysis. British Journal of Industrial Relations 60: 324–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnett, Nick, and Stephen Hardy. 2001. Reviewing the Working Time Directive: Rationale implementation and case law. Industrial Relations Journal 32: 114–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andringa, Wouter, Rense Nieuwenhuis, and Minna Van Gerven. 2015. Women’s working hours: The interplay between gender role attitudes, motherhood, and public childcare support in 23 European countries. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 35: 582–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, Lucía. 2021. Gender Inequalities in Working Time and Health in Europe. In Gender, Working Conditions and Health. What Has Changed? Brussels: ETUI. Available online: https://www.etui.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/2_Gender%20inequalities%20in%20working%20time%20and%20health%20in%20Europe.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Artazcoz, Lucía, and Anabel Gutiérrez Vera. 2012. Gender differences in the relationship between long working hours and health status in Catalonia. Archivos de Prevencion de Riesgos Laborales 15: 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Artazcoz, Lucía, Imma Cortès, Fernando G. Benavides, Vicenta Escribà-Agüir, Xavier Bartoll, Hernán Vargas, and Carme Borrell. 2016. Long working hours and health in Europe: Gender and welfare state differences in a context of economic crisis. Health & Place 40: 161–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askenazy, Philippe. 2004. Shorter work time, flexibility and intensification. Eastern Economic Journal 30: 603–14. [Google Scholar]

- Askenazy, Philippe. 2013. Working time regulation in France from 1996 to 2012. Cambridge Journal of Economics 37: 323–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, Jessica, and Annick Masselot. 2012. Gender equality law and identity building for Europe. Canterbury Law Review 18: 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Berniell, Inés, and Jan Bientenbeck. 2017. The Effect of Working Hours on Health. IZA DP 10524 IZA–Institute of Labor Economics. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/izaizadps/dp10524.htm (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Bosch, Gerhard, and Steffen Lehndorff. 2001. Working-time reduction and employment: Experiences in Europe and economic policy recommendations. Cambridge Journal of Economics 25: 209–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Alison L., Marco Francesconi, and Jeff Frank. 2002. Temporary jobs: Stepping stones or dead ends? The Economic Journal 112: 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, Brendan, and Colette Fagan. 2004. Gender and the intensification of work: Evidence from the European Working Conditions Surveys. Eastern Economic Journal 30: 627–42. [Google Scholar]

- Calmfors, Lars. 1985. Work sharing, employment and wages. European Economic Review 27: 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, Rosemary, Suzan Lewis, and Clare Lyonette, eds. 2007. Women, Men, Work and Family in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dembe, Allard E. 2009. Ethical issues relating to the health effects of long working hours. Journal of Business Ethics 84: 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembe, Allard E., J. B. Erickson, Rachel G. Delbos, and Steven M. Banks. 2005. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: New evidence from the United States. Occupational & Environmental Medicine 62: 588–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIGE. 2018. Study and Work in the EU: Set Apart by Gender: Review of the Implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action in the EU Member States. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- EIGE. 2019. Gender Equality Index 2019: Portugal. European Institute for Gender Equality. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2019 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eurofound. 2006. Working Time Options over the Life Course: New Work Patterns and Company Strategies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_files/pubdocs/2005/160/en/1/ef05160en.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Eurofound. 2009. Working Conditions in the European Union: Working Time and Work Intensity. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2009/working-conditions-european-union-working-time-and-work-intensity (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eurofound. 2010. Stereotypes about Gender and Work. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/resources/article/2010/stereotypes-about-gender-and-work (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Eurofound. 2013a. Women, Men and Working Conditions in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2013/women-men-and-working-conditions-europe (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Eurofound. 2013b. Working Time and Work–Life Balance in a Life Course Perspective—A Report Based on the Fifth European Working Conditions Survey. Dublin: Eurofound. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2013/working-time-and-work-life-balance-life-course-perspective (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Eurofound. 2016. Working Time Developments in the 21st Century: Work Duration and Its Regulation in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2016/working-time-developments-21st-century-work-duration-and-its-regulation-eu (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eurofound. 2017. Developments in Working Time 2015–2016. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2017/developments-working-time-2015-2016 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eurofound. 2018. Striking a Balance: Reconciling Work and Life in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2018/striking-balance-reconciling-work-and-life-eu (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eurofound. 2019. Working Time in 2017–2018. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2019/working-time-2017-2018 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Eurofound. 2020. Labour Market Change: Trends and Policy Approaches towards Flexibilisation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2020/labour-market-change-trends-and-policy-approaches-towards-flexibilisation (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Eurofound. 2021a. European Jobs Monitor 2021: Gender Gaps and the Employment Structure. Joint Report by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and Eurofound. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2021/european-jobs-monitor-2021-gender-gaps-and-employment-structure (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Eurofound. 2021b. Portugal: Working life in the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2021/working-life-covid-19-pandemic-2020 (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Eurofound, and ILO (International Labour Office). 2017. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Geneva: The International Labour Office. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2017/working-anytime-anywhere-effects-world-work (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- European Commission. 2009. Gender Segregation in the Labour Market: Root Causes, Implications and Policy Responses in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/39e67b83-852f-4f1e-b6a0-a8fbb599b256 (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- European Commission. 2015. Strategic Engagement for Gender Equality 2016–2019. SWD(2015)278 Final. Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/24968221-eb81-11e5-8a81-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- European Commission. 2020. Europe’s Digital Progress Report (EDPR) 2017, Country Profile Portugal. Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://www.astrid-online.it/static/upload/port/portugaledprcountryprofile.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- European Parliament & the Council of the European Union. 2006. Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (recast). Official Journal of the European Union, L 204/23. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament & the Council of the European Union. 2024. Directive (EU) 2024/1500 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 May 2024 on standards for equality bodies in the field of equal treatment and equal opportunities between women and men in matters of employment and occupation, and amending Directives 2006/54/EC and 2010/41/EU. Official Journal of the European Union, 24/1500. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, Colette, Clare Lyonette, Mark Smith, and Abril Saldaña-Tejeda. 2012. The Influence of Working Time Arrangements on Work-Life Integration or ‘Balance’: A Review of the International Evidence. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Ann R., and Kenna Bolton Holz. 2007. Perceived discrimination and women’s psychological distress: The roles of collective and personal self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54: 154–64. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Richard B. 1998. Work-sharing to full employment: Serious option or populist fallacy? In Generating Jobs: How to Increase Demand for Less-Skilled Workers. Edited by Richard Freeman and Peter Gottschalk. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ganster, Daniel, Christopher Rosen, and Gwenith Fisher. 2018. Long working hours and well-being: What we know, what we do not know, and what we need to know. Journal of Business and Psychology 33: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnsey, Elizabeth. 1978. Women’s work and theories of class stratification. Sociology 12: 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershuny, Jonathan. 2000. Chaging Times: Work and Leisure in Postindustrial Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Lonnie. 2012. The Effects of Working Time on Productivity and Firm Performance: A Research Synthesis Paper. ILO Conditions of Work and Employment Series, WP 33. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2149325 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Haines, Victor, Alain Marchand, Émilie Genin, and Vicent Rousseau. 2012. A balanced view of long work hours. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 5: 104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, Catherine. 2005. Reconciling Work and Family Responsibilities. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://webapps.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2005/105B09_142_engl.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, and Carolyn Buck Luce. 2006. Extreme jobs: The dangerous allure of the 70-hour workweek. Harvard Business Review 84: 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hook, Jennifer L., and Becky Pettit. 2016. Reproducing occupational inequality: Motherhood and occupational segregation. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 23: 329–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. 2005. Hours of Work. From Fixed to Flexible? Report of the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (Articles 19, 22 and 35 of the Constitution), Report 93 III. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2018a. Decent Work in Portugal 2008–18: From Crisis to Recovery. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_646867.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- ILO. 2018b. Global Wage Report 2018/19: What Lies Behind Gender Pay Gaps? Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_650553.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- ILO. 2020. Global Wage Report 2020/21: Wages and Minimum Wages in the Time of COVID-19. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/global-wage-report-2020-21-wages-and-minimum-wages-time-covid-19 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Kay, Rachel. 2020. Automation and Working Time in the UK. In Work in the Future, The Automation Revolution. Edited by Robert Skidelsky and Nan Craig. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, Clare, and Deirdre Anderson. 2010. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations 63: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, Evelyn. 1998. Changing Gender Roles, State, Work and Family Lives. In Women, Work and the Family in Europe. Edited by Eileen Drew, Ruth Emerek and Evelyn Mahon. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 153–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, Hadas, and Moshe Semyonov. 2006. A welfare state paradox: State interventions and women’s employment opportunities in 22 countries. American Journal of Sociology 111: 1910–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melby, Kari, Anna-Birte Ravn, and Christina Carlsson Wetterberg. 2008. A Nordic Model of gender equality? Introduction. In Gender Equality and Welfare Politics in Scandinavia—The Limits of Political Ambition? Edited by Kari Melby, Anna-Birte Ravn and Christina Carlsson Wetterberg. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MTSSS. 2016. Livro Verde Sobre as Relações Laborais 2016. MTSSS. Available online: https://www.portugal.gov.pt/download-icheiros/ficheiro.aspx?v=%3d%3dBAAAAB%2bLCAAAAAAABAAzNjI0BwAQG9WaBAAAAA%3d%3d (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- MTSSS. 2021. Livro Verde Sobre o Futuro do Trabalho. MTSSS. Available online: https://www.portugal.gov.pt/download-ficheiros/ficheiro.aspx?v=%3d%3dBQAAAB%2bLCAAAAAAABAAzNLQwMQMAqSscTAUAAAA%3d (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Neschen, Albena, and Sabine Hügelschäfer. 2021. Gender Bias in Performance Evaluations: The Impact of Gender Quotas. Journal of Economic Psychology 85: 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2015. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/deliver/9789264235120-en.pdf?itemId=/content/publication/9789264235120-en&mimeType=pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- OECD. 2016. New Forms of Work in the Digital Economy. OECD Digital Economy Papers 260. Paris: OCDE. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5jlwnklt820x-en.pdf?expires=1707245325&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=E7329FAE1002319B41F9B6CB6D585633 (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- OECD. 2017. Hours Worked. Paris: OECD. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Parry, Jane, Zoe Young, Stephen Bevan, Michail Veliziotis, Yehuda Baruch, Mina Beigi, Zofia Bajorek, Emma Salter, and Chira Tochia. 2021. Working from Home under COVID-19 Lockdown: Transitions and Tensions, Work after Lockdown. Swindon: Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC). Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/446405/1/Work_After_Lockdown_Insight_report_Jan_2021_1_.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Rebelo, Glória. 2019. Working Time Organization: Influences in Work-family Balance and Career. International Journal on Working Conditions 18: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, Sheila. 1981. Women and working time. Equal Opportunities International 1: 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rubery, Jill, and Isabel Tavora. 2021. The COVID-19 crisis and gender equality: Risks and opportunities. In Social Policy in the European Union: State of Play 2020: Facing the Pandemic. Edited by B. Vanhercke, S. Spasova and B. Fronteddu. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) and European Social Observatory (OSE), pp. 71–96. Available online: https://www.etui.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/06-Chapter4-The%20Covid%E2%80%9119%20crisis%20and%20gender%20equality.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Rubery, Jill, Mark Smith, and Colette Fagan. 1998. National Working-Time Regimes and Equal Opportunities. Feminist Economics 4: 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, Jill, Mark Smith, and Colette Fagan. 1999. Women’s Employment in Europe: Trends and Prospects. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Helen, Philip J. O’Connell, and Frances McGinnity. 2009. The impact of flexible working arrangements on work–life conflict and work pressure in Ireland. Gender, Work and Organization 16: 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scase, Richard, Jonathan Scales, and Colin Smith. 1999. Long working hours hurt health and family. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, Andrew, Zara Lipsey, and Jane Wardle. 1998. Stress, hassles and variations in alcohol consumption, food choice and physical exercise: A diary study. British Journal of Health Psychology 3: 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Trzcinski, Eileen, and Elke Holst. 2011. Why Men Might “Have It All” While Women Still Have to Choose between Career and Family in Germany. The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) Papers, WP 356. Available online: https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.367187.de/diw_sp0356.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- UN. 2006. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2006. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/zh/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDGReport2006.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- UN. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

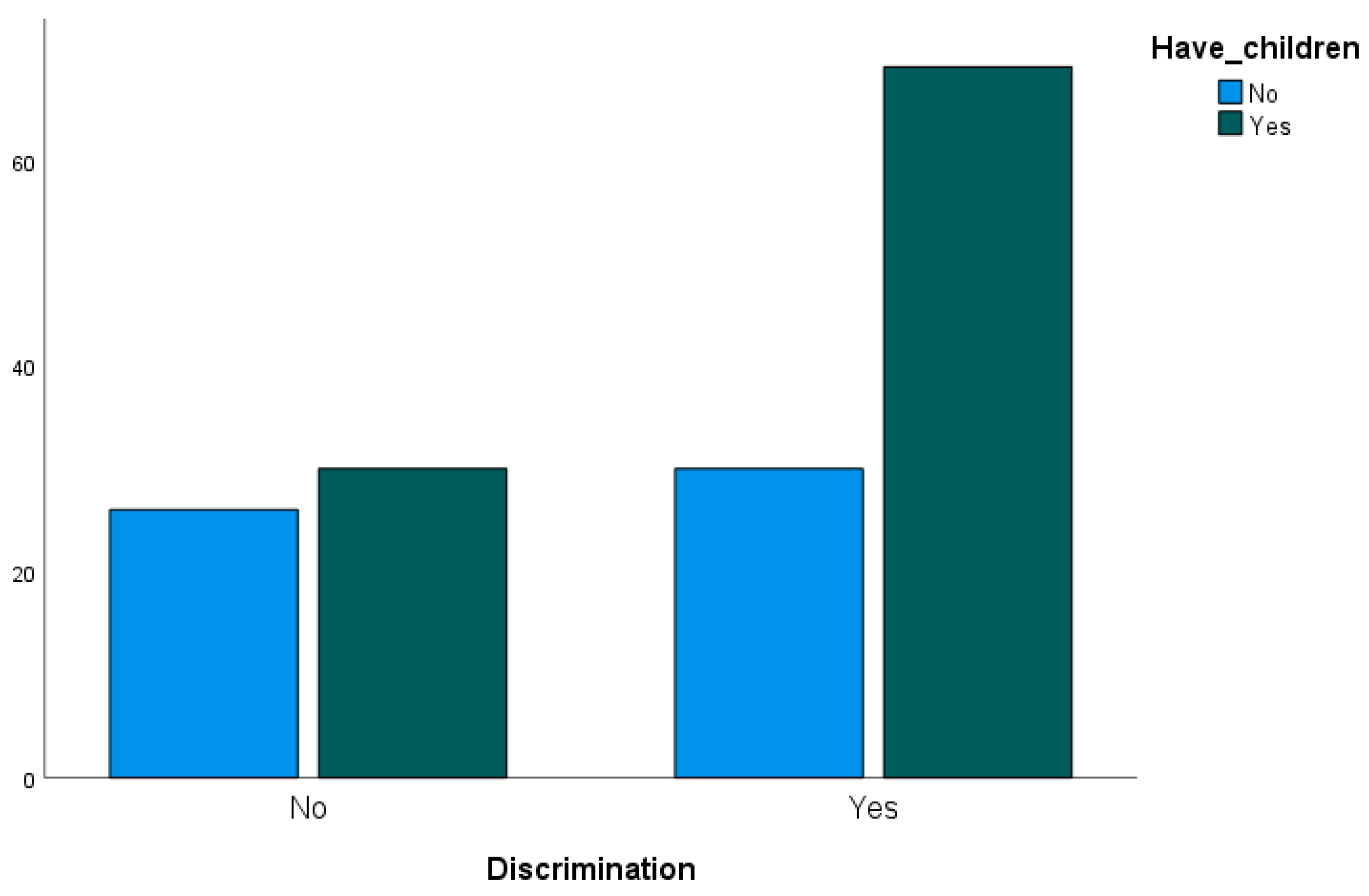

| Q.9 (n = 155) | Age Group | n (%) | N.º of Children | n (%) | Education Level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–35 | 11 (11.1) | None | 30 (30.3) | Up to the 9th grade | 2 (0.02) | |

| Yes | 36–50 | 52 (52.5) | One | 28 (28.3) | Up to the 12th grade | 19 (19.2) |

| 99 (63.9%) | ≥51 | 36 (36.4) | Two | 37 (37.4) | Degree | 31 (31.3) |

| Three or more | 4 (0.04) | P-grad./master’s/doct. Degree | 47 (47.5) | |||

| 18–35 | 21 (0.4) | None | 26 (46.4) | Up to the 9th grade | 0 (0) | |

| No | 36–50 | 24 (42.9) | One | 20 (35.7) | Up to the 12th grade | 9 (16.1) |

| 56 (36.1%) | ≥51 | 11 (19.6) | Two | 7 (0.1) | Degree | 31 (55.4) |

| Three or more | 3 (0.05) | P-grad./master’s/doct. Degree | 16 (26.6) |

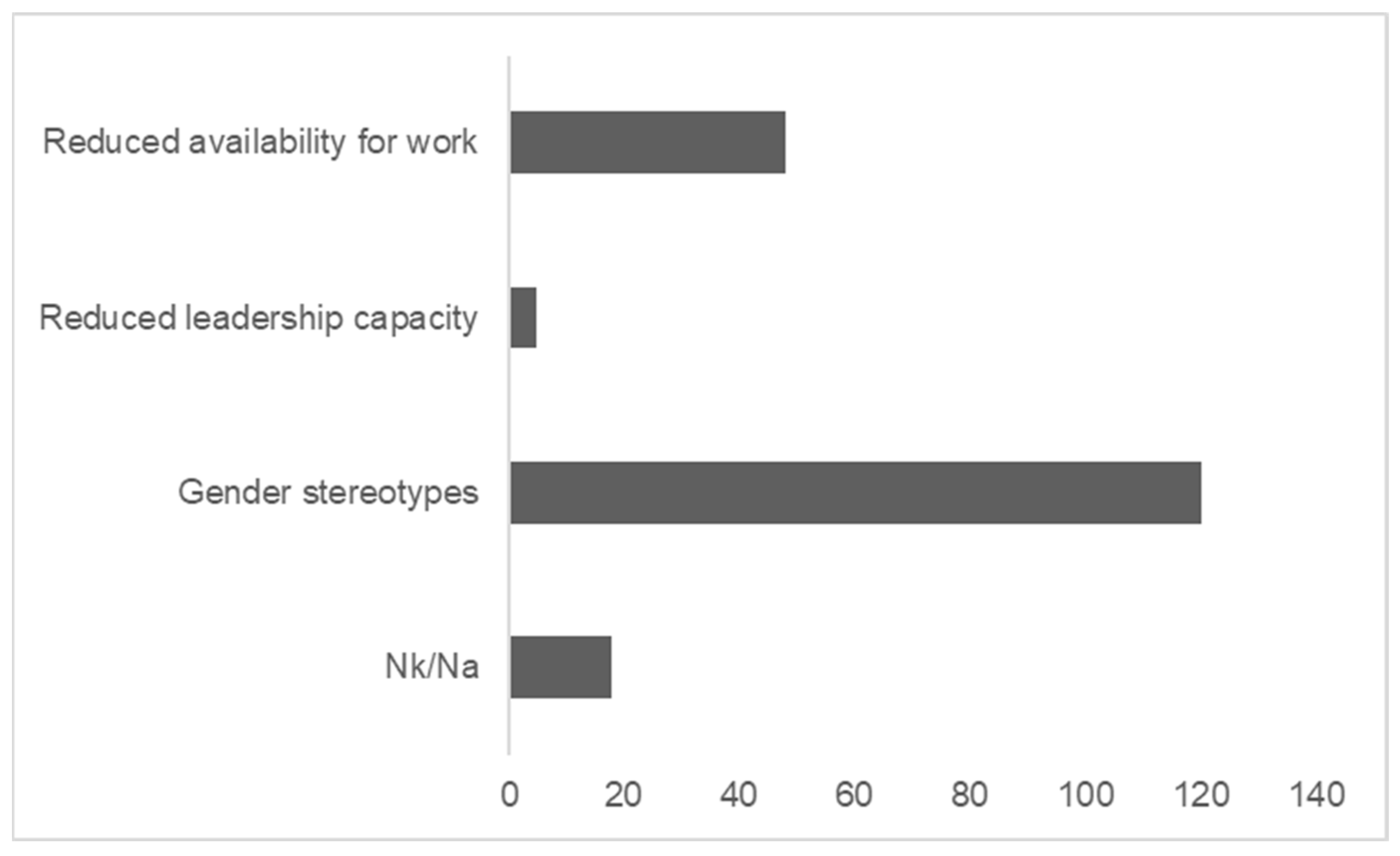

| Q.10 (Yes, n = 99) | Age Group | n (%) | N.º of Children | n (%) | Education Level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–35 | 7 (10.1) | None | 23 (33.3) | Up to the 9th grade | 2 (2.9) | |

| “gender stereotypes” | 36–50 | 40 (58.0) | One | 16 (23.2) | Up to the 12th grade | 14 (20.3) |

| 69 (69.7%) | ≥51 | 22 (31.9) | Two | 27 (39.1) | Degree | 20 (29.0) |

| Three or more | 3 (4.4) | P-grad./master’s/doct. Degree | 33 (47.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rebelo, G.; Delaunay, C.; Martins, A.; Diamantino, M.F.; Almeida, A.R. Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination at Work: Gender Stereotypes and Overtime—An Exploratory Study in Portugal. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080188

Rebelo G, Delaunay C, Martins A, Diamantino MF, Almeida AR. Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination at Work: Gender Stereotypes and Overtime—An Exploratory Study in Portugal. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(8):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080188

Chicago/Turabian StyleRebelo, Glória, Catarina Delaunay, Alexandre Martins, Maria Fernanda Diamantino, and António R. Almeida. 2024. "Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination at Work: Gender Stereotypes and Overtime—An Exploratory Study in Portugal" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 8: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080188

APA StyleRebelo, G., Delaunay, C., Martins, A., Diamantino, M. F., & Almeida, A. R. (2024). Women’s Perceptions of Discrimination at Work: Gender Stereotypes and Overtime—An Exploratory Study in Portugal. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080188