Abstract

The hospitality and tourism (H&T) sector, marked by intense employee–customer interactions, dynamic labor shifts, and high physical and emotional labor demands, faces chronic talent acquisition and retention. Therefore, tailored employer branding (EB) strategies that address the unique characteristics of the H&T sector are essential for improving the current situation. Despite the critical need for tailored solutions, a clear and unified approach for H&T companies to effectively manage their EB strategies, including the development of a compelling employee value proposition (EVP) that resonates with targeted professionals, has yet to be established. Following the PRISMA reporting guidelines, a systematic literature review of 30 peer-reviewed articles from the Scopus and Web of Science databases was conducted to synthesize existing research on EB practices in the H&T sector. The results reveal a fragmented literature that lacks a cohesive framework for categorizing and measuring EVP. The use of varied and inconsistent EVP models and scales across studies hampers comparative analysis and limits the development of generalizable insights. Furthermore, the review highlights a concentration of research within the hotel industry, leaving other important H&T industries, such as the restaurant and cruise industries, underexplored. This SLR emphasizes the urgent need for a unified approach to EB in H&T. Based on these results, promising research avenues are suggested to further advance EB research in H&T, along with managerial implications for enhancing talent attraction and retention in the sector.

1. Introduction

While the hospitality and tourism (H&T) sector thrives on delivering exceptional customer experiences, which are crucial for its business model, it often overlooks the employee experience. This oversight contributes to the sector’s well-known unfavorable reputation for poor working conditions, exemplified by its weak employee value proposition (EVP), characterized by low wages and long, unpredictable work schedules that hinder work/life balance. Consequently, this has resulted in high employee turnover rates and, more recently, worker shortages, further complicating the situation for employers (Azimi et al., 2024; Innerhofer et al., 2024; King et al., 2021).

The H&T sector’s success hinges on exceptional customer experiences, directly influenced by employee performance, skills, and emotional well-being (Innerhofer et al., 2024; Michael et al., 2023; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022; Thao et al., 2024). Thus, attracting and retaining skilled and engaged employees is paramount for sustainable growth. Hence, a deeper understanding of how to enhance employer attractiveness is essential (Kar & Phuong, 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Muisyo et al., 2022; Näppä et al., 2023).

Employer branding (EB), defined as the strategic process of creating a compelling employment proposition to attract and retain targeted employees (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004), emerges as a critical approach for improving H&T’s employer appeal (Azimi et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Kar & Phuong, 2023; Kilson et al., 2024; Manoharan et al., 2023; Näppä et al., 2024; Zografou & Galanaki, 2024). Investments in EB enable H&T companies to refine their EVP and effectively communicate their value to both potential and current employees. EB may also significantly improve job advertising by highlighting the positive aspects of employment, including unique benefits, such as company culture, while clearly outlining job requirements and responsibilities. This targeted approach contributes to attracting candidates who align with both the role and the company culture, thereby increasing the likelihood of long-term retention. Moreover, effective EB fosters a positive and inclusive work environment, directly enhancing the experience of current employees and further strengthening retention. Consequently, ongoing research into EB advancements within the H&T sector is essential for overcoming challenges related to employee attraction and retention, ultimately driving sustainable growth.

Since the seminal work by Ambler and Barrow (1996), employer branding research has evolved into a dynamic field, significantly expanding each year (Saini et al., 2022). Among the key insights gleaned from years of research into employer branding is the necessity of considering the unique characteristics of each sector and company (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Dabirian et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2025; Kim & Legendre, 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Plaikner et al., 2023). In other words, there is no one-size-fits-all approach for all companies. Just as companies exhibit diverse characteristics, such as organizational values and job development policies, so too do professionals’ employment preferences within those organizations (Kilson et al., 2024; Plaikner et al., 2023), highlighting the need for segmentation of the professional market (Moroko & Uncles, 2009).

The travel and tourism sector accounted for 9.1% of the global gross domestic product, equating to nearly USD 10 trillion, and supported 10% of jobs worldwide, approximately 330 million positions (WTTC, 2024). These figures illustrate the sector’s significance as both an employer and a research context that necessitates design-specific studies addressing its unique employment conditions.

Driven by hospitable interactions, the diverse H&T sector (hotels, restaurants, airlines, etc.) presents unique employment characteristics: physically demanding work (Kilson et al., 2024), high customer interaction (Innerhofer et al., 2024), irregular hours (Guo et al., 2025), low pay (Coaley, 2021; Guo et al., 2025), a socially diverse workforce, and limited qualification requirements (Kilson et al., 2024). Some of these characteristics result in high emotional demands (Kilson, 2021), challenges in achieving work/life balance (Guo et al., 2025), increased employee turnover rates (King et al., 2021), and difficulties in attracting and retaining qualified employees (Brown et al., 2015; Kilson, 2021), necessitating a sector-specific employer branding approach (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; King et al., 2021; Näppä et al., 2024).

Recognizing the importance of segmentation in successfully implementing an EB strategy, researchers have examined the effects of employer branding on employee attraction and retention in the H&T sector, offering insights into critical components of EVP and effective communication strategies (e.g., Coaley, 2021; Kar & Phuong, 2023; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025). However, the literature lacks standardization. The application of various EVP scales and inconsistent terminology across studies resulted in a fragmented landscape, impeding the creation of a unified framework for practical EB strategies that H&T managers can adopt. Therefore, closing the gap between research findings and practical application is essential for the H&T sector to effectively address employee attraction and retention challenges, requiring the development of precise, consistent terminology and frameworks that enhance research progress and facilitate EB practices adoption among managers.

To help synthesize key EB insights and organize the literature, a systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted on employer branding practices in the H&T sector. The SLR aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of H&T employer branding research, focusing on the following:

- -

- The data collection context.

- -

- The data collection methods adopted.

- -

- The theory adopted.

- -

- The best employer branding practices to attract and retain talented employees.

While other employer branding SLRs have been conducted (e.g., I. Reis et al., 2021; Saini et al., 2022; Theurer et al., 2018), this SLR uniquely focuses on the H&T sector. This targeted approach offers crucial theoretical insights for future research, assists researchers in clarifying conclusions, and provides valuable managerial insights, including a detailed list of key EVP components, to enhance employer branding strategies and tackle talent challenges in the H&T sector.

2. Methods

This systematic literature review adhered to the process outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline (PRISMA, 2020).

2.1. Data Collection

Studies were selected from the Scopus and Web of Science databases, two commonly used standard article databases for systematic literature reviews (SLRs), including prior research on employer branding (e.g., I. Reis et al., 2021; Saini et al., 2022). Journals included in both databases have their published content evaluated to ensure the quality of the information in their articles (Clarivate, n.d.; Elsevier, n.d.). Additionally, both databases allow researchers to apply relevant filters, such as peer-reviewed journals and keywords, enabling a more precise search and excluding non-relevant content.

As King et al. (2021) discuss, the H&T sector is complex and challenging to describe accurately. Indeed, studies often utilize various terms to refer to it, including the hospitality industry, hospitality sector, and H&T industry, among others. This sector is a broad field comprising various industries where meaningful human interaction is essential for business success. These industries include, but are not limited to, restaurants and hotels. To initiate the search, a set of keywords was established along with their corresponding combinations (e.g., “Employer Branding” and “Hospitality”). Table 1 presents the list of keyword combinations.

Table 1.

List of keyword combinations.

These keyword combinations were initially searched in the titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles on Scopus. Subsequently, they were tested again on Web of Science. The aim of searching for keywords within these three components was to ensure the articles’ relevance to this research. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included. No specific time frame was established. Articles were retrieved in November 2024. On 3 February and 1 April 2025, both databases were checked for updates, resulting in the inclusion of a few new studies.

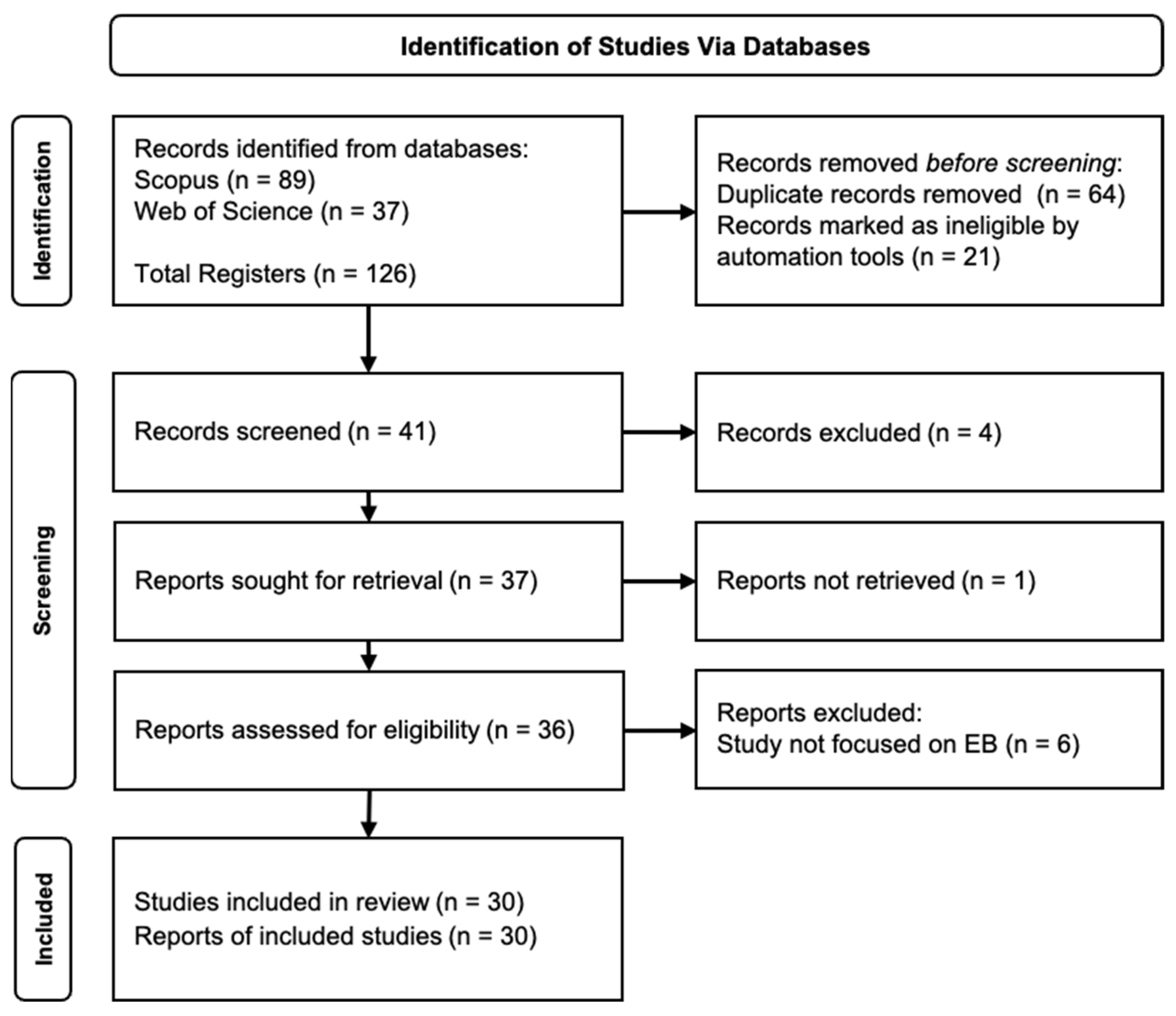

The search in the Scopus and Web of Science databases yielded 126 results. Of these, 21 were automatically filtered out by the platforms for not being published in peer-reviewed journals, while another 64 were duplicates; these appeared in searches with different keyword selections or across both databases. After removing duplicate articles, the abstracts were reviewed to assess their alignment with the objectives of this study. This study aimed to understand the implications of employer branding for the H&T sector and to compare the findings of these studies, so only articles focused exclusively on this sector were included, resulting in the exclusion of four articles.

Subsequently, the remaining articles were retrieved for further review. However, since one of the 37 remaining articles was no longer accessible on the journal’s website, and it was not possible to contact the corresponding author, only 36 articles were retrieved. Six of the 36 articles reviewed did not concentrate on EB despite containing the keywords. These six studies did not discuss the concept, only briefly mentioning it compared to other topics or indicating potential implications for employer branding. In the end, 30 articles were included in this study. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA Flow Diagram containing all the steps and results of the study selection process used in this review.

Figure 1.

Study selection process. Source: based on the PRISMA flow diagram (PRISMA, 2020).

2.2. Data Analysis

Given the substantial amount of data generated, the first step in interpretation involved organizing and summarizing it. To achieve this, the method chosen was thematic analysis. This method is used to systematically identify and interpret recurring patterns in the data, ultimately structuring them into meaningful themes. This process was guided by the six-step framework outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006).

Data familiarization, the first step, involved thoroughly reviewing all articles and, simultaneously, initial notetaking. Following this, an initial list of codes was developed (Step 2). The definition of code labels followed a bottom-up approach. This means that, despite considering the research objectives—namely, to identify the studies’ data collection methods and context, the theories adopted, and best employer branding practices—no codes were applied a priori. Instead, all code labels were generated during Step 2. Following this initial coding phase, the codes were then organized into broader themes (Step 3). As Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 82) articulate, “A theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” Consequently, the significance of a theme is judged by its relevance to the central research question, rather than solely by quantifiable measures. To ensure the integrity of the themes, their content was reanalyzed to confirm their internal coherence and distinctiveness in relation to one another (Step 4). Once their suitability was established, names that best encapsulated their essence were selected (Step 5). The final step (Step 6) involved writing the concluding report, which presented the most significant findings for each theme and discussed the relationships observed between them.

To illustrate this coding process, consider extracts that explicitly mention the EVP scale or model, such as “[…] a widely recognized and established categorization in marketing is instrumental and symbolic attributes […] (Lo et al., 2025, p. 3).” These were labeled with the code “EVP Scale/Model”.

Subsequently, these individual codes were grouped into broader categories to facilitate a visual understanding of their connections. It was from these categories that the initial themes began to emerge and were subsequently refined. Furthermore, subthemes were identified within each theme. The subthemes offer a more detailed and nuanced understanding of each main insight developed from the themes. Table 2 provides a comprehensive list of the codes used in the analysis, along with illustrative examples of the extracts that informed their labels.

Table 2.

List of codes.

3. Results

Before presenting the themes and subthemes, Table 3 provides an overview of the 30 studies included in this SRL. Notably, the oldest identified studies date back to 2018, indicating that EB research focusing on the H&T sector took over 20 years to develop since the concept was introduced. Since then, EB research in H&T has significantly expanded, particularly in 2022, possibly revealing a growing recognition of the relevance of EB in reducing employment challenges in H&T.

Table 3.

List of studies.

Regarding data collection methods, researchers have employed different approaches to investigate employer branding practices, such as observation, focus groups, and manual/automated online secondary data collection. However, traditional methods were the most common, with surveys being the most frequently used method; 17 (56.67%) of the studies relied on this approach, and 15 (50%) used surveys exclusively for data collection. Semi-structured interviews were the second most common data collection method, utilized by seven (23.33%) of the studies, while four (13.33%) relied solely on this type of interview. Furthermore, five (16.67%) studies, excluding those based on the academic literature, considered secondary data such as internal organizational documents, job advertisements, and employer online reviews.

The studies were conducted in very different contexts regarding geographical locations, participants, business sizes, categories, and industries. Another relevant observation is the clear emphasis on the hotel industry, with 21 (70%) of the studies including hotels, of which 15 (50%) focused exclusively on this industry. Additionally, among those who specified the hotel category, five (16.67%) concentrated on luxury hotels (4- and 5-star hotels), while one (3%) focused on mid-scale to luxury hotels (3- and 4-star hotels), indicating a greater interest in upper-scale companies. Supporting this perspective, the only study examining the restaurant industry also explored luxury establishments.

In total, 15 studies (50%) explicitly stated that they had adopted at least one of the 11 identified theories to guide their analyses. While displaying significant theoretical diversity, most studies relied on well-established theories related to EB research: signaling theory (eight studies, 26.67%), social identity theory (three studies, 10%), and social exchange theory (three studies, 10%).

Thus, the findings indicate that EB research in H&T is relatively recent but already provides a diverse perspective, offering valuable insights that are explored further in the following themes and subthemes.

3.1. Themes and Subthemes Description

Table 4 illustrates all themes and their respective subthemes developed through the analysis processes of the 30 articles considered.

Table 4.

List of themes and subthemes.

3.1.1. Employee Value Proposition

At the core of EB research is the exploration of how employers define their EVP and what constitutes a compelling EVP that differentiates a company from others, establishing it as the employer of choice (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Mohamad et al., 2018; Näppä et al., 2023). In this sense, regular conversations with employees (Guo et al., 2025; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022), employee segmentation (Guo et al., 2025; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025), the analysis of the competition’s offerings (Kilson et al., 2024), and the observation of how new trends emerge as societal needs change (Azhar et al., 2024; Bagheri et al., 2023; Santos et al., 2023) are all essential steps to ensuring that a company’s EVP is unique, updated, and relevant to targeted professionals (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Näppä et al., 2023). In this regard, researchers identified numerous employee benefits and proposed various models to categorize them.

The absence of a unified EVP scale and model. The lack of a standardized Employee Value Proposition (EVP) scale and model presents a significant challenge. While studies focusing on H&T companies have explored the impact of employer branding (EB) on employee experience and employer attractiveness, they have employed diverse EB scales (e.g., Berthon et al., 2005; Chopra et al., 2024; Bussin & Mouton, 2019; Tanwar & Prasad, 2017). This fragmented approach, where researchers often introduce new labels for existing concepts, has drawn criticism. For instance, Guo et al. (2025) argued that a single model should be adopted to enhance research consistency.

The EmpAT scale (Berthon et al., 2005), encompassing five core dimensions—Application Value, Development Value, Economic Value, Interest Value, and Social Value—has been widely adopted in general EB literature and, consequently, in H&T research (e.g., Kim & Legendre, 2023; Michael et al., 2023; Mohamad et al., 2018). Building upon the EmpAT scale, some researchers proposed expansions. In this sense, Dabirian et al. (2017) proposed a seven-dimensional model by adding Work/Life Balance and Management Value. Meanwhile, Kar and Phuong (2023) proposed the addition of the Security Value dimension.

Although not initially intended for the H&T sector, Dabirian et al.’s (2017) model has gained support among H&T researchers. Guo et al. (2025) suggested adapting the model’s content to the H&T context while keeping the original dimension labels for consistency. Likewise, Kilson et al. (2024) applied the seven-dimension model to the hotel industry, further expanding it to a nine-dimension model by incorporating Authenticity (G. G. Reis et al., 2017) and Social Diversity while preserving the seven original dimensions.

Employee value proposition components. An employer may offer its employees a variety of benefits. The specific benefits provided by each employer largely depend on various factors, including location, available resources, the profile of employees they aim to attract and retain, as well as competition, business segment, and organizational values (Kilson et al., 2024). Nonetheless, it is possible to identify trends in employee benefits within the literature that are directly related to shared characteristics of the work experience in the H&T sector, which allows for a description of the unique components of the EVP in this sector (Guo et al., 2025).

Due to varying shifts and the necessity of often working during weekends and holidays, work/life balance is one of the most emphasized employee benefits by researchers (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Azhar et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Innerhofer et al., 2024; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Plaikner et al., 2023; Santos et al., 2023; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022). Some effective methods to promote a better work/life balance include introducing flexible work hours to help employees manage personal matters (Azhar et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022), sharing workloads (Azhar et al., 2024), and providing childcare support (Lo et al., 2025; Plaikner et al., 2023). However, achieving a work/life balance can be challenging since work schedules often change due to seasonality and high employee turnover (Guo et al., 2025).

Attractive compensation packages, including a base salary, free meals at the local, health insurance, paid time off, and job security, are essential for fostering a positive employer brand (Azhar et al., 2024; Coaley, 2021; Guo et al., 2025; Innerhofer et al., 2024; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Mohamad et al., 2018; Näppä et al., 2024; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022). Nevertheless, they are among the most requested enhancements (Coaley, 2021; Guo et al., 2025; Kim & Legendre, 2023). Taweewattanakunanon and Darawong (2022) assert that these benefits should reflect the business category. Therefore, luxury businesses, which typically demand more specialized staff, should provide even more appealing compensation.

Career development opportunities rank among the most discussed benefits (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Azhar et al., 2024; Coaley, 2021; Kilson et al., 2024; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kim & Legendre, 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Mohamad et al., 2018; Näppä et al., 2024; Plaikner et al., 2023; Thao et al., 2024). These opportunities encompass learning sessions, whether through on-the-job training or formal education (Azhar et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Lo et al., 2025; Näppä et al., 2024; Thao et al., 2024), job rotation, which allows employees to grasp the relevance of the diverse activities within the H&T sector (Kilson et al., 2024; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022; Thao et al., 2024), and experiences abroad (Azhar et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kilson et al., 2024). Clearly defined promotion paths are also crucial for evaluating employer brand (Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kim & Legendre, 2023). However, like compensation, career development opportunities are frequently perceived negatively by employees (Coaley, 2021; Näppä et al., 2024), particularly due to issues related to excessive workloads and employee turnover that detract from employees’ professional growth (Guo et al., 2025).

Researchers emphasize the importance of promoting a positive work atmosphere (Coaley, 2021; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kilson et al., 2024). In this regard, aspects that employers should consider include promoting employee recognition (Guo et al., 2025; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kim & Legendre, 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Mohamad et al., 2018; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022; Thao et al., 2024), fostering a collaborative culture (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Azhar et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kim & Legendre, 2023; Plaikner et al., 2023), nurturing positive relationships among employees and managers (Coaley, 2021; Guo et al., 2025; Kilson et al., 2024; Plaikner et al., 2023; Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022), and fomenting employee communities (Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025). Additionally, employers should promote a sense of meaningful work (Kapuściński et al., 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Thao et al., 2024) and a sense of purpose (Coaley, 2021) by highlighting how their work positively impacts others (Näppä et al., 2024), such as by creating unique and memorable guest experiences (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Lo et al., 2025). Again, high employee turnover may adversely affect a company’s ability to maintain a positive work atmosphere, as remaining employees must continually adapt to new colleagues, including new managers (Guo et al., 2025).

Other less frequent benefits include cultivating a sense of pride in being part of a reputable company by sharing positive feedback from external stakeholders and recognizing awards received (Lo et al., 2025; Thao et al., 2024). Companies can also enhance their reputation by promoting environmental responsibility and ethical workplace relationships (Lo et al., 2025; Santos et al., 2023; Thao et al., 2024) while nurturing supportive connections with stakeholders, including local communities, especially during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (Bagheri et al., 2023). Furthermore, by allowing employees to express their personal preferences about appearance, such as hairstyle, tattoos, and piercings, companies promote authenticity among their staff (Kilson et al., 2024). Finally, promoting a socially diverse organization can enhance a company’s employer brand by encouraging the exchange of varied life perspectives and establishing a welcoming environment for diverse employees (Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025).

3.1.2. Job Opportunities Promotion

In addition to developing an attractive EVP, it is crucial to communicate the company’s employer positioning clearly and appealingly, enabling potential candidates to assess their fit with the organization’s demands, values, and benefits. Consequently, as a key element of any EB strategy, the way companies promote their job opportunities has been extensively examined (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Jerez-Jerez et al., 2021; Kilson et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2018; Lo et al., 2025). Beyond merely announcing their intention to hire new employees, employers must consider the signals that their job offering messages convey and how potential candidates perceive these signals (Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Manoharan et al., 2023). Thus, defining a communication strategy is vital for attracting the right professionals; otherwise, the EB strategy may prove ineffective (Manoharan et al., 2023).

The relevance of the match between the employee and the employer. One of the primary objectives of a successful EB strategy is to ensure a match between employees’ and employers’ expectations regarding job requirements, activities, organizational values, and the EVP. Just as customers seek the product or service that best meets their needs and desires, the same applies to employment. Both employees and employers want to ensure they make the right decision when selecting candidates or hiring for a position (Kilson et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2018; Lo et al., 2025).

In this context, research has shown that EB is essential for ensuring potential candidates evaluate their person–job fit (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2018). This is pertinent because, the greater the perception of fit, the stronger the candidate’s intention to apply for a job. Consequently, this contributes to establishing a company as the employer of choice among targeted professionals. This is particularly significant when attracting candidates with no prior experience, such as H&T undergraduate students, who represent a valuable pool of skilled professionals. These individuals often leave the sector due to a mismatch between their employment expectations and the realities of the industry (Lin et al., 2018). Additionally, a high person–job fit enhances employee performance and satisfaction, fostering a mutually beneficial relationship (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024).

In addition to hiring employees who meet job demands, employers must ensure that potential candidates align with the company’s values (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Jerez-Jerez et al., 2021; Kilson et al., 2024; Näppä et al., 2023) since this alignment is also relevant to employees’ loyalty, comfort, enthusiasm, and performance (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Jerez-Jerez et al., 2021; Näppä et al., 2023), contributing to the development of employer brand equity and positively influencing customer experience (Näppä et al., 2023). Therefore, regardless of the communication methods employed, employers must ensure that their job offerings are attractive and precise (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Kilson et al., 2024).

Designing attractive and precise job offering communications. Companies must be cautious with their job offerings to ensure they are hiring suitable employees. Therefore, all job advertisements should highlight the positive aspects of the employment experience and provide clear and sufficient information to enable potential candidates to determine if they are a good fit for the company (Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025). Given the increasing importance of online communication, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic (Bagheri et al., 2023), researchers have investigated how online platforms can be used to showcase a company’s employer brand and attract candidates (Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Oncioiu et al., 2022; Zografou & Galanaki, 2024).

Employers should take advantage of online communication channels (Bagheri et al., 2023; Lo et al., 2025), such as the company’s website and platforms like LinkedIn, to enhance their employer brand awareness and positively shape their reputation (Oncioiu et al., 2022; Zografou & Galanaki, 2024). To achieve this, employers should share comprehensive information about their employer brands on their websites, including detailed descriptions of their EVP, such as CSR activities, development opportunities, and workplace environments, among others. Additionally, employers should utilize these platforms to showcase their brands, organizational values, and how these are integrated into the company’s operations, alongside employee testimonials and third-party certifications that bolster the credibility of the information. When announcing job opportunities, employers must avoid vague descriptions. They should provide sufficient information regarding the technical and social requirements, a description of the company, the brand segment, the job location, the work team, and, whenever possible, the specific work schedule (Kilson et al., 2024).

Employers should pay attention to what current and former employees say about their work experiences. In addition to directly asking employees, managers can also follow online conversations on employer review websites, where they can find valuable, spontaneous feedback to improve their EB strategy (Coaley, 2021).

Researchers have also highlighted the importance of current and former employees as ambassadors for their employers (Bagheri et al., 2023; Näppä et al., 2023; Plaikner et al., 2023; Thao et al., 2024). Employees share their work experiences within their networks and inform others about job vacancies at their company. In this way, employees serve as a valuable source of potential candidates (Thao et al., 2024). Since employees are familiar with the company’s working conditions, they can identify professionals who are likely to be a good fit, aiding the company in promoting job opportunities to the targeted audience (Näppä et al., 2023).

Employees must be viewed as essential EB partners who help shape and promote the employer brand, thereby contributing to brand equity (Näppä et al., 2023; Plaikner et al., 2023). Therefore, employers should encourage employees’ participation in the recruiting process, as their involvement can enhance recruiting effectiveness (Bagheri et al., 2023). This requires that employees comprehend the organizational values, how they influence their work, and the unique aspects of the company’s EVP (Näppä et al., 2023).

In the end, employers must ensure that their external communications align with the company’s reality (Manoharan et al., 2023). Misalignment can damage a company’s employer brand among potential and current employees (Coaley, 2021). Therefore, employers must ensure transparent and regular communication both internally and externally (Jerez-Jerez et al., 2021).

3.1.3. Employer Branding as a Remedy for the H&T’s Employment Challenges

The H&T sector has a notoriously unfavorable reputation as an employer, mainly offering job positions that do not require specific skills (Kilson et al., 2024). As a result, it is prone to high employee turnover rates and shortages (Azimi et al., 2024; Innerhofer et al., 2024). In this context, most researchers argue that improving EB practices is essential for addressing the challenges of employee attraction and retention in the H&T sector (Azhar et al., 2024; Azimi et al., 2024; Jerez-Jerez et al., 2021; Kar & Phuong, 2023; Kilson et al., 2024; Kim & Legendre, 2023; Lo et al., 2025; Manoharan et al., 2023; Michael et al., 2023; Näppä et al., 2023; Näppä et al., 2024; Santos et al., 2023; Thao et al., 2024).

Employer branding effects on employees’ work experience. Developing a strong employer brand rooted in a positive relationship between employers and employees can reduce turnover and enhance employee satisfaction, retention, identification, and loyalty. Specifically, offering financial benefits, fostering a safe, secure, respectful, and supportive environment, and providing career growth opportunities are crucial in decreasing employees’ intention to leave (Kar & Phuong, 2023). Additionally, positive relationships among employees, career advancement opportunities, and particularly competitive salaries may increase employees’ brand love by enhancing their perceived value congruence with the company (Kim & Legendre, 2023).

Additionally, Azimi et al. (2024) found that enhancing the appeal of the employer brand personality through investments in CSR can positively influence employee satisfaction and turnover intention. Accordingly, the sector’s reputation is linked to its attractiveness as an employer, which affects employees’ intention to remain in the sector (Näppä et al., 2024).

Remuneration, task significance, work/life balance, and workplace relationships positively contribute to employee job satisfaction. Satisfied employees demonstrate higher loyalty levels to their employers and are more likely to recommend them (Taweewattanakunanon & Darawong, 2022). Similarly, a strong company’s reputation, job rotation, and training programs can also positively influence employee job satisfaction. Furthermore, the company’s reputation and providing challenging and meaningful jobs contribute to increased organizational identification. Research shows that both job satisfaction and organizational identification predict employees’ intentions to refer their employer to potential candidates (Thao et al., 2024). Furthermore, environmentally responsible companies may enjoy enhanced employer attractiveness, increased job pursuit intentions, and higher job offer acceptance (Muisyo et al., 2022). Finally, EB is positively related to improved person–job fit, which, in turn, enhances employee performance and engagement (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024), consequently boosting organizational performance (Azhar et al., 2024).

To reap these benefits, managers must see EB as an ongoing strategy that requires consistency. This strategy begins long before employees join the company. It starts when organizations define and present their employer positioning to potential candidates (Kilson et al., 2024) and continues even after employees end their formal relationship with the organization. This sustained strategy is essential for attracting temporary employees back to the company during peak seasons and converting former employees into employer ambassadors (Näppä et al., 2023).

From single employers to a sectoral collaboration to repositioning the H&T sector. Given the well-known reputation of the H&T sector as an employer, some studies suggest that EB should extend beyond individual company boundaries to address the sector’s employment challenges (Manoharan et al., 2023; Näppä et al., 2024). This broader perspective necessitates that employers cultivate closer relationships with diverse stakeholders. In this context, employers should collaborate with H&T schools, enabling students to gain early exposure to the sector’s realities, including its employment opportunities and challenges. This strategy helps students evaluate their person–job fit before applying, increasing the likelihood of alignment with future employers and their intentions to seek employment in the H&T sector (Lin et al., 2018).

Furthermore, while it is crucial for each employer to develop its own EB strategy, including a compelling EVP, employers must recognize that their company’s appeal is closely linked to the sector’s overall attractiveness (Näppä et al., 2024). As a result, even if a company cultivates a strong employer reputation, it may still find it challenging to attract talented employees since many professionals might be hesitant to seek employment in the H&T sector due to its negative reputation (Manoharan et al., 2023). Therefore, employers and relevant sector entities should collaborate to establish standard practices related to working conditions and effectively promote their unique benefits that are unparalleled in other sectors (Näppä et al., 2024). In other words, to tackle its talent shortage and high employee turnover, the H&T sector should set long-term goals to enhance its talent branding (Manoharan et al., 2023).

Michael et al. (2023) note that providing appealing employment conditions can also positively affect customers’ experiences and perceptions of the broader context, thereby increasing the destination’s appeal and promoting the sustainability of businesses. Nevertheless, to be effective, EB must be prioritized by employers (Santos et al., 2023) and integrated into the overall business strategy (Oncioiu et al., 2022). Ultimately, beyond offering employees positive experiences, employers contribute to their communities by investing in their EB strategies.

The employment context and employee segmentation. Finally, some researchers addressed the nuances that large international or small family businesses may need to consider when defining their EB strategy (Japutra et al., 2024; Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025; Plaikner et al., 2023; Zografou & Galanaki, 2024), highlighting the importance of taking the broader context into account (Al-Romeedy et al., 2024; Kim & Legendre, 2023; Lo et al., 2025).

In terms of company size, some studies indicate that, while large internal hotel chains have fully embraced employer branding (EB) practices, demonstrating clear and formal EB strategies (Kilson et al., 2024), small, often family-owned businesses typically adopt a more informal approach to these practices (Plaikner et al., 2023; Zografou & Galanaki, 2024).

For instance, Plaikner et al. (2023) found that small family businesses often adopt a more informal approach to managing their EB practices. While they recognize the significance of creating a positive employment experience to retain employees, small business managers generally lack a cohesive EB strategy. Indeed, these managers frequently perceive the implementation of a formal EB strategy as a complicating factor in business management, which seems appropriate only for large companies. Despite this informality, small employers actively invest in EB to enhance their attractiveness (Zografou & Galanaki, 2024). Likewise, Lo et al. (2025) found that hotel chains tend to showcase their EVP in job advertisements more frequently than independent hotels. The authors also discovered that hotel chains present a more diverse range of EVP components compared to their independent counterparts.

Meanwhile, Kilson et al. (2024) identified several signals on the recruitment websites and job advertisements of large international companies that reflect a clear EB strategy. These signals included job postings that highlight the company’s global reputation, mentions of best employer awards, and comprehensive lists of potential employee benefits on their recruiting websites. However, with numerous business units spread across various locations, challenges related to EB communications may arise, such as significant variability in how the employer is represented in different regions. In this regard, Japutra et al. (2024) emphasize the difficulties in implementing a cohesive EB strategy across all locations due to cultural differences. By adopting a one-size-fits-all approach, employers risk overlooking relevant contextual employment factors, which hampers their ability to become the employer of choice. At the same time, employers must be cautious not to lose their identity, facing the challenge of balancing their core identity elements with the local context.

As Plaikner et al. (2023) point out, both large and small businesses face unique challenges and opportunities. Factors that significantly affect employees’ experiences, such as the employer–employee relationship and salary range, are greatly shaped by a company’s size. In this context, while larger companies may provide higher salaries, smaller businesses often foster stronger social connections with their employees (Kapuściński et al., 2023; Plaikner et al., 2023).

Employers should also consider the differences among employee segments and company characteristics (Kapuściński et al., 2023; Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025). Employees may be segmented by education level, gender (Kilson et al., 2024), work experience (Guo et al., 2025; Kapuściński et al., 2023), and generation (Klumaier et al., 2024).

To illustrate, Klumaier et al. (2024) found that employees from Generations X, Y, and Z attribute different levels of importance to career opportunities, instrumental and symbolic characteristics, task attractiveness, and work ethics and values. More specifically, employees from Generation X value mentoring programs more than their Generation Y and Z counterparts. Meanwhile, Generation Y employees generally seek less feedback. Concerning instrumental and symbolic characteristics, Generation Z employees are more interested in team activities than their Generation Y counterparts. Additionally, Generation X employees tend to be more influenced by sustainable practices than Generation Y and Z employees.

Work experience may also influence employees’ preferences. By segregating employer reviews based on the number of years employees held their positions, Guo et al. (2025) found that those who had held their positions for less than three years often cited benefits such as friendly colleagues, which contribute to a family atmosphere, flexible schedules, and positive experiences for guests. Meanwhile, those who worked in the same role for three or more years often mentioned benefits related to career development, like job promotions and international transfers, health insurance, tips, free meals, and good leadership. Additionally, current and former employees expressed notable differences in their comments, with former employees typically showing more positive sentiments toward expanding their skills and work experience and negative sentiments regarding providing excellent customer service and career advancement.

3.2. Complementary Results

This section outlines the complementary results that were not produced through the coding process. Table 5 presents several insights developed during the analysis based on the theoretical frameworks employed by the researchers. Although presented separately, these insights are meant to be understood as mutually reinforcing. The interconnectedness of specific theories, such as the resource-based view and market-based view, or image theory and brand equity theory, makes this complementarity particularly apparent.

Table 5.

Theoretical insights for employer branding in hospitality and tourism.

4. Discussion

This SLR objective was to provide a comprehensive perspective on employer branding research within the H&T sector. Although the earliest studies date back to 2018, with most published since 2022—indicating emerging research—the results revealed otherwise. Supporting this view, the majority of studies relied on quantitative surveys designed to assess the potential effects of EB on various employee outcomes, such as job satisfaction, turnover intention, and organizational identification. The use of theories commonly associated with the general EB literature, such as signaling and social identity theories, along with the application of widely adopted EB scales, further reinforces this perspective. This can primarily be explained by the fact that the general EB literature has developed over the last three decades. Thus, while it took two decades for EB studies dedicated to the H&T sector to emerge, the core EB concepts and models were already established. Therefore, a significant portion of these studies incorporates insights from the general EB literature as they are, occasionally making minor adjustments to better suit their purpose and context.

On the one hand, maintaining a consistent approach and language that reflects the broader EB literature is essential. This enables the comparison of conclusions from these H&T studies with those from non-H&T studies and allows their insights to be considered by a wider range of researchers and practitioners, thereby contributing to a more extensive and cohesive body of literature.

On the other hand, relying on general assumptions derived from the broader EB literature, particularly the EVP models and their associated scales, may not be the most appropriate approach since they were not designed with the unique employment characteristics of the H&T sector in mind, as noted by Guo et al. (2025) and discussed by other researchers after conducting their data analysis (e.g., Mohamad et al., 2018).

Therefore, it is essential to strike a balance between consistency and adaptation, as some researchers have achieved by relying on established EVP models while keeping an open perspective on how the previously described EVP dimensions manifest in the H&T sector (e.g., Guo et al., 2025). In some cases, this has led to the proposal of new dimensions that were not previously identified (e.g., Kilson et al., 2024).

The results also indicated that researchers utilized various EVP models and scales to categorize EVP components and assess their impact on companies. While most scholars relied on the well-established work of Berthon et al. (2005), a few referenced its expanded version proposed by Dabirian et al. (2017). Although there is no single correct method to categorize the various employee benefits that employers may offer, this diversity complicates efforts to compare these studies and hinders future research. This raises the question of whether it is time to develop an EVP model and scale specifically designed for the H&T sector. In this regard, the description of the main EVP components in this study serves as a relevant starting point. In alignment with Guo et al.’s (2025) call for consistency in EVP terminology and building upon the foundational five-dimension EmpAT model (Berthon et al., 2005)—Application Value, Development Value, Economic Value, Interest Value, and Social Value—this research proposes an expanded and adapted version of the EmpAT model for the H&T sector.

This model incorporates dimensions identified by subsequent researchers, including Management Value and Work/Life Balance (Dabirian et al., 2017), Authenticity (G. G. Reis et al., 2017), Security Value (Kar & Phuong, 2023), and Social Diversity (Kilson et al., 2024). Crucially, unlike alternative models that introduce entirely new labels (e.g., Coaley, 2021), this proposed model preserves established terminology, enhancing clarity and facilitating comparative research within the H&T sector. This new H&T EVP model is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

H&T EVP model.

Another notable aspect is the emphasis on the hotel industry. Over half of the studies examined focus on hotels, suggesting that many other H&T industries remain underexplored. For instance, only one study specifically related to the restaurant industry was identified (Jerez-Jerez et al., 2021). Even within the hotel industry, among the studies that explicitly mentioned the hotels category, most focused on luxury establishments. In terms of the business category, which is a significant contextual factor for EB, many studies neglect to mention this information. Often, researchers analyze various businesses without providing additional details (e.g., company size, business category, and type) (e.g., Näppä et al., 2023). While examining diverse businesses collectively is acceptable, as it may aim to uncover patterns among them, providing more contextual details can reveal further insights, such as whether the business category might moderate the relationship between specific EVP components and desired employee outcomes.

As expected, since EB focuses on shaping how employers position themselves to enhance their attractiveness to targeted professionals, most studies have concentrated on the perspectives of H&T employees, including current and former employees as well as potential candidates. In contrast, only a few studies have considered employers (business owners) and/or HR managers (e.g., Zografou & Galanaki, 2024), while just two examined employers brand’s communications (Kilson et al., 2024; Lo et al., 2025). While employees are the central focus, understanding how to develop strong employer brands requires including other relevant information sources. These sources can include company owners, HR managers, H&T schools, experts, sector entities, and employer brand communications from companies, such as job advertisements and websites (Kilson et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2018; Lo et al., 2025; Manoharan et al., 2023; Näppä et al., 2024). Therefore, researchers should expand their data collection efforts to include additional perspectives that enrich employees’ viewpoints.

Finally, results indicate that no universal EB strategy exists. It will be greatly influenced by how companies position themselves as employers and the types of professionals they aim to attract and retain. Even within the H&T sector, significant differences may arise, as work in the aviation industry is substantially different from that in the cruise or restaurant industries. Therefore, as the H&T EB literature evolves with more studies exploring a diverse range of industries, it may be relevant to conduct an SLR targeting specific H&T industries.

5. Conclusions

Despite the importance of the H&T sector as a global employer, it continues to experience high employee turnover and shortages due to its working conditions, thus perpetuating its unfavorable reputation. One solution to this challenge is to invest in EB to enhance employees’ experiences and, in turn, improve the sector’s attractiveness. Although the EB literature has expanded significantly, researchers have highlighted the need to consider the employment context to better understand how specific contextual factors influence companies’ employer brands and the overall image of the sector in which they operate. While many insights into EB have been developed, some may not apply specifically to the H&T sector, as most studies have not focused on it. Consequently, an SLR was conducted to provide a comprehensive perspective on the evolution of EB research in the H&T sector. It focused on the data collection contexts and methods of these studies, the theories adopted, and the findings regarding best practices in employer branding to attract and retain talented employees.

The results revealed significant diversity across geographical contexts. Studies were conducted across four continents, primarily in Asia and Europe, and encompassed a range of markets (e.g., restaurants, tourist retail) and business sizes (e.g., family-owned companies and global chains). The findings also indicated that most participants who explicitly identified the business category focused on the luxury segment. Similarly, the hotel industry was the most frequently considered among the various industries comprising the H&T sector.

Regarding the data collection methods used, the most common approach was quantitative surveys, followed by semi-structured interviews. Other data methods included manual and automated online secondary data collection, focus groups, literature reviews, and observations. In most cases, the primary data sources were the current employees and managers of H&T companies; very few alternative sources, such as online employer reviews and recruiting websites, were considered.

Half of the studies explicitly indicated that they adopted a specific theory to guide their data analysis. Eleven theories were mentioned, with some studies employing more than one. The three most commonly used theories—signaling theory, social identity theory, and social exchange theory—are also prevalent in general EB literature, with signaling theory being the most frequently adopted, alone or in conjunction with other theories.

Lastly, the results revealed several employer branding practices that help H&T companies attract and retain talented employees. Key practices include listening to employees when defining their EVP and enabling them to co-create the company’s employer brand. Additionally, employers should thoughtfully promote their job opportunities to ensure that job advertisements clearly outline the job description and highlight the unique aspects of the employment experience.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first EB SLR focused on H&T studies. By pursuing this goal, we hope to establish a new direction in EB research tailored to the H&T sector, enhance clarity and managerial utility in future research, and thereby improve the sector’s appeal for employment.

This SLR enhances clarity and managerial utility in future research on EB in H&T by reinforcing the necessity for clear research contextualization (e.g., describing the type and category of businesses). While insights from research on EB practices in luxury restaurants may be relevant to other restaurant segments, specific details may not apply to, for example, fast-food restaurants. The same applies to studies encompassing businesses from different industries, such as hotels and restaurants. It is crucial for researchers to explicitly state which businesses they are considering in their study, avoiding generic descriptions, such as hospitality businesses.

Moreover, despite extensive exploration of the H&T sector, it is demonstrated that most of our knowledge concerns the hotel industry. In contrast, other sectors, such as the restaurant, aviation, and cruise industries, are still underexplored, limiting our understanding of how investments in EB might benefit H&T companies and the best approaches to implementing EB strategies. Similarly, most studies focus on employees’ perspectives, leaving the other side, the employers, underexplored. Since EB aims to enhance employers’ ability to attract and retain targeted employees, it is crucial to consider the employer’s perspective.

This SLR also corroborated Guo et al.’s (2025) critique regarding the lack of standardization in EVP categorization, highlighting the resulting challenges in comparing research findings. To address this issue, this study proposes an expanded, ten-dimensional version of the widely adopted EmpAT EVP model (Berthon et al., 2005). This model integrates new insights from prior H&T employer branding research while maintaining the original EmpAT dimension labels. This approach fosters a more consistent framework for future studies, facilitating comparative analysis and advancing the field. These contributions are further translated into concrete suggestions for future research.

Lastly, the 11 theories in Table 5 provide a rich foundation for future exploration of the EB phenomenon within the H&T sector. By drawing on these theories, either individually or in combination, researchers can generate novel insights into EB. For instance, future research could investigate the synergy between the Market-Based View and Means–End Chain Theory to understand how H&T employers might strategically adapt their EVP and its communication to resonate with evolving societal priorities, such as sustainability. This could reveal how to effectively convey that the organization supports career progression while contributing to a sustainable future, thereby enhancing employee attraction and retention. Furthermore, the integration of Image Theory and Social Influence Theory holds promise for understanding how changes in H&T job requirements (e.g., requiring a university degree for intermediate positions) could reshape the perceptions of influential figures like parents and friends of H&T students regarding the sector’s attractiveness as an employer, subsequently influencing the students’ inclination to apply for H&T positions.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Attracting and retaining talented employees in the competitive H&T sector demands a strategic approach to building a compelling employer image. This requires managers to meticulously consider all facets of the employment experience, from location and business focus to performance evaluations and uniforms. These elements collectively shape current and potential employees’ perceptions of the company.

Therefore, managers must clearly define their business positioning, including their target customer segment. This clarity is crucial for aligning their employer brand with the professionals they aim to attract and retain, ultimately contributing to positive organizational performance. To achieve this alignment, Human Resource and Marketing managers need consistent communication. They should share insights on evolving customer and employee preferences and perceptions, and collaboratively determine necessary company adjustments to align these with the value proposition. For example, if customers increasingly desire personalized service, managers should actively solicit employee input on how to tailor experiences. Furthermore, providing employees with the necessary resources, such as enhanced training, is vital to equip them for delivering unique customer experiences. Consequently, managers may need to revise their performance evaluation processes and job advertising to reflect these employer brand adaptations.

However, overcoming talent challenges in H&T extends beyond individual company efforts. Collaboration with key partners, including H&T schools, competitors, and industry organizations, is essential for establishing a broadly appealing sector employer brand. For instance, partnering with H&T schools to facilitate in-person student visits can offer firsthand sector experience. Joint efforts could also focus on developing engaging internship programs that present students with real-world challenges, demonstrating the practical value of their skills. Similarly, collaboration with competitors to establish minimum working conditions ensures that H&T employees have multiple attractive employment options within the sector, mitigating employee shortages if they leave their current employers.

Regarding the EVP composition, while a wide range of benefits (as detailed in Table 6, from career stability to flexible dress codes) are relevant, managers should prioritize addressing well-known sources of employee dissatisfaction: low salaries, heavy workloads, lack of work/life balance, and limited career development opportunities.

Given the large workforce in H&T, small and independent businesses often face difficulties offering significant salary increases. Therefore, managers can strategically enhance employees’ perception of their compensation by providing valuable economic benefits. These can include free workplace meals, health insurance, product discounts, matching contribution retirement plans, performance-based bonuses, paid time off, and tips. Incorporating some or all of these benefits can strengthen the EVP and differentiate the company, often proving more cost-effective than direct salary increases.

Addressing heavy workloads requires managers to analyze and revise internal routines to identify and eliminate bottlenecks that cause delays and employee stress. For example, implementing mobile ordering systems can reduce the need for waiters to manually take orders at each table. Investing in job rotation programs allows for the swift redistribution of staff to areas with the highest demand. Furthermore, providing regular breaks and comfortable break rooms alleviates employee fatigue. It is important to note that many employee benefits are interconnected. By offering, for example, healthy free meal options, employers are not only enhancing employees’ perceptions regarding their remuneration but also alleviating problems related to work fatigue associated with heavy workloads.

Managers should focus on work schedule planning to improve work/life balance. Whenever feasible, employees should have at least one day off per week, including both weekdays and weekends, to attend to personal activities. Offering paid time off also significantly contributes to employees’ perception of work-life balance. Recognizing that many H&T employees are also students, providing a degree of autonomy in managing their schedules to accommodate academic commitments is vital for retention. The same principle applies to employees with childcare responsibilities who may require flexibility.

Investing in career development opportunities is also crucial. This includes communicating potential career paths and outlining the necessary steps for growth. As previously mentioned, job rotation programs facilitate the development of broader skill sets. Regular training sessions are also essential to make employees feel valued and up-to-date. Beyond traditional training, programs should incorporate how employees can leverage new digital technologies, such as AI and augmented reality, in their daily tasks.

Furthermore, managers should consider other important EVP components unique to the sector, such as providing opportunities for culturally diverse experiences and enabling employees to create memorable moments for guests. This can be achieved by fostering a culture of social diversity and inclusion, where employees from various backgrounds share their experiences. Empowering employees to share insights on the personalization of guest experience and sharing positive feedback demonstrates the value of their contributions.

Despite the diverse examples of EVP components, managers must recognize the unique context of their own company, including available resources and workforce. Therefore, it is paramount to actively engage with employees to understand areas for improvement and how to achieve them. Instead of solely relying on satisfaction surveys or online reviews, managers should encourage employees to proactively propose ideas for enhancing the work experience and strengthening the company’s employer brand.

Ultimately, managers must remember that the H&T sector, being highly labor-intensive, heavily relies on employee performance for business success. Therefore, ensuring adequate working conditions, job satisfaction, and a sense of inclusion should be integral topics in their business strategy discussions.

5.3. Limitations

For all SLRs, it is essential to consider specific keyword combinations, databases, and types of studies to ensure that relevant works are included. However, this approach also risks overlooking other significant studies that may not meet these criteria. Therefore, while relying on two relevant databases that include thousands of journals and not setting a specific timeframe for the article search, this SLR did not consider other sources, such as Google Scholar, which covers a broader range of works, including articles published in journals not indexed by Scopus and Web of Science. Additionally, while various keyword combinations were included, other relevant alternatives that could generate a broader sample of articles may not have been considered.

Focusing exclusively on studies in the H&T sector enabled a more segmented view of employer branding practices that can help employers better manage their positioning and offer valuable theoretical insights for future research. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this is a highly diverse sector, comprising various industries that, while sharing specific employment characteristics, also exhibit differences. For instance, the working conditions in an airline are not equivalent to those in a theme park. Similarly, defining a comprehensive list of the industries that make up this sector is challenging, which is reflected in the keyword combinations used during data collection that focus on the hotel and restaurant industries and general H&T companies. Moreover, it is essential to note that most studies in this SLR concentrated on the hotel industry. In contrast, fewer studies have examined other relevant industries, such as the restaurant, cruise, aviation, and theme park industries, among others. Therefore, caution is necessary when generalizing these results to these other industries.

Lastly, while maintaining an open perspective on what the data analysis may reveal, the research objectives shaped the interpretation of the results, narrowing this study’s focus and influencing what was deemed relevant insights. Thus, what is presented here represents only one of many possible interpretations of the results. Different research objectives and data analysis methods could have uncovered additional relevant insights.

5.4. Future Research

This SLR identified promising future research opportunities within the selected studies and enabled the presentation of new research suggestions in Table 7. We hope this list will inspire researchers to further explore employer branding practices in the H&T sector.

Table 7.

Future research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., El-Bardan, M. F., & Badwy, H. E. (2024). How is employee performance affected by employer branding in tourism businesses? Mediation analysis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(2), 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A., Rehman, N., Majeed, N., & Bano, S. (2024). Employer branding: A strategy to enhance organizational performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 116, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M., Sadeghvaziri, F., Ghaderi, Z., & Hall, C. M. (2024). Corporate social responsibility and employer brand personality appeal: Approaches for human resources challenges in the hospitality sector. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 33(4), 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M., Baum, T., Mobasheri, A. A., & Nikbakht, A. (2023). Identifying and ranking employer brand improvement strategies in post-COVID 19 tourism and hospitality. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(3), 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. A., Thomas, N. J., & Bosselman, R. H. (2015). Are they leaving or staying: A qualitative analysis of turnover issues for generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussin, M., & Mouton, H. (2019). Effectiveness of employer branding on staff retention and compensation expectations. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A., Sahoo, C. K., & Patel, G. (2024). Exploring the relationship between employer branding and talent retention: The mediation effect of employee engagement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(4), 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. (n.d.). Resources for librarians and administrators. Available online: https://clarivate.libguides.com/librarianresources/coverage (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Coaley, P. C. (2021). Online employer reviews: A glimpse into the employer-brand benefits of working in the Las Vegas hotel/casino industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 20(3), 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabirian, A., Kietzmann, J., & Diba, H. (2017). A great place to work!? Understanding crowdsourced employer branding. Business Horizons, 60(2), 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. (n.d.). Scopus content. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus/content (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Guo, Y., Ayoun, B., & Zhao, S. (2025). Is someone listening to me? A topic modeling approach using guided LDA for exploring hospitality value proposition through online employee reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 127, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerhofer, J., Nasta, L., & Zehrer, A. (2024). Antecedents of labor shortage in the rural hospitality industry: A comparative study of employees and employers. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(1), 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A., Situmorang, R., Mariani, M., & Pereira, V. (2024). Understanding employer branding within MNC subsidiaries: Evidence from MNC hotel subsidiaries in Indonesia. Journal of International Management, 30(1), 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez-Jerez, M. J., Melewar, T., & Foroudi, P. (2021). Exploring waiters’ occupational identity and turnover intention: A qualitative study focusing on Michelin-starred restaurants in London. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuściński, G., Zhang, N., & Wang, R. (2023). What makes hospitality employers attractive to Gen Z? A means-end-chain perspective. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 29(4), 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A., & Phuong, T. N. T. (2023). Investigating the influences of employer branding attributes on turnover intentions of hospitality workforce in the COVID-19 in Vietnam. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(5), 2173–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilson, G. A. (2021). Career opportunities in the hotel industry: The perspective of hotel management undergraduate’s students from the City of São Paulo. Marketing & Tourism Review, 6(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilson, G. A., de Lurdes Calisto, M., & Peres, R. (2024). An analysis of online employer positioning: Insights for a broader employee value proposition construct in the hotel industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 23(2), 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., & Legendre, T. S. (2023). The effects of employer branding on value congruence and brand love. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(6), 962–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C., Madera, J. M., Lee, L., Murillo, E., Baum, T., & Solnet, D. (2021). Reimagining attraction and retention of hospitality management talent—A multilevel identity perspective. Journal of Business Research, 136, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumaier, V., Zehrer, A., & Spieß, T. (2024). Generational Attitudes in SME Family Hotels: Practical Implications for Employer Brand Profiles. European Journal of Family Business, 14(1), 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M., Chiang, C., & Wu, K. (2018). How hospitality and tourism Students Choose Careers: Influences of employer branding and applicants’ customer orientation. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 30(4), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A., Huang, Z., Buhalis, D., Thomas, N., & Pang, J. M. (2025). Mapping the landscape of employer value propositions in Asian hotels through online job postings analysis. Tourism Management, 110, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, A., Scott-Young, C., & McDonnell, A. (2023). Industry talent branding: A collaborative and strategic approach to reducing hospitality’s talent challenge. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(8), 2793–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N., Michael, I., & Fotiadis, A. K. (2023). The role of human resources practices and branding in the hotel industry in Dubai. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 22(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, S. F., Sidin, S. M., Dahlia, Z., Ho, J. A., & Boo, H. C. (2018). Conceptualization of employer brand dimensions in Malaysia luxury hotels. International Food Research Journal, 25(6), 2275–2284. [Google Scholar]

- Moroko, L., & Uncles, M. D. (2009). Employer branding and market segmentation. Journal of Brand Management, 17(3), 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P. K., Qin, S., Julius, M. M., Ho, T. H., & Ho, T. H. (2022). Green HRM and employer branding: The role of collective affective commitment to environmental management change and environmental reputation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(8), 1897–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najam, Z., Nisar, Q. A., Hussain, K., & Nasir, S. (2022). Enhancing Employer Branding through Virtual Reality: The role of E-HRM Service Quality and HRM Effectiveness in the Hotel Industry of Pakistan. Asia-Pacific Journal of Innovation in Hospitality and Tourism, 11(2), 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Näppä, A., Styvén, M. E., & Foster, T. (2023). I just work here! Employees as co-creators of the employer brand. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 23(1), 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näppä, A., Styvén, M. E., & Robertson, J. (2024). Employment in the tourism and hospitality industry: Toward a unified value proposition. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(1), 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I., Anton, E., Ifrim, A. M., & Mândricel, D. A. (2022). The influence of social networks on the digital recruitment of human resources: An empirical study in the tourism sector. Sustainability, 14(6), 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaikner, A., Haid, M., Kallmuenzer, A., & Kraus, S. (2023). Employer branding in tourism: How to recruit, retain and motivate staff. Journal of Tourism and Services, 14(27), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. (2020). PRISMA flow diagram. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Reis, G. G., Braga, B. M., & Trullen, J. (2017). Workplace authenticity as an attribute of employer attractiveness. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1962–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, I., Sousa, M. J., & Dionísio, A. (2021). Employer Branding as a Talent Management Tool: A Systematic Literature revision. Sustainability, 13(19), 10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, G. K., Lievens, F., & Srivastava, M. (2022). Employer and internal branding research: A bibliometric analysis of 25 years. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(8), 1196–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V., Simão, P., Reis, I., Sampaio, M. C., Martinho, F., & Sousa, B. (2023). Ethics and Sustainability in Hospitality Employer Branding. Administrative Sciences, 13(9), 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styvén, M. E., Näppä, A., Mariani, M., & Nataraajan, R. (2022). Employee perceptions of employers’ creativity and innovation: Implications for employer attractiveness and branding in tourism and hospitality. Journal of Business Research, 141, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2017). Employer brand scale development and validation: A second-order factor approach. Personnel Review, 46(2), 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweewattanakunanon, R., & Darawong, C. (2022). The influence of employer branding in luxury hotels in Thailand and its effect on employee job satisfaction, loyalty, and intention to recommend. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 21(4), 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, H. T., Kim, L. H., & Kim, Y. (2024). Employer Branding: How current employee attitudes attract top talent and new customers. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurer, C. P., Tumasjan, A., Welpe, I. M., & Lievens, F. (2018). Employer Branding: A brand equity-based literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTTC. (2024). Travel & tourism economic impact research (EIR). Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Zografou, I., & Galanaki, E. (2024). To “talk the walk” or to “walk the talk”? Employer branding and HRM synergies in small and medium-sized hotels. EuroMed Journal of Business, 20(5), 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]