Relationship between Leadership and Characteristics of Learning Organizations in Deployed Military Units: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Learning Organizations

| Shared Vision | The discipline of creating a shared picture of the future that fosters genuine commitment and engagement. In an organization, a shared vision binds people together around a common identity and a sense of destiny, giving a sense of purpose and coherence to all activities undertaken. |

| Team Learning | The discipline of raising the collective IQ of a group and capitalizing on the greater knowledge and insights of the collectivity. This implies dialogue and overcoming patterns of defensiveness that undermine group learning. |

| Personal Mastery | The discipline of continually clarifying and deepening employees’ personal visions, and focusing their energies. This includes awareness of personal weaknesses and growth areas as well as humility, objectivity and the persistent willingness to pursue self-development. |

| Mental Models | The discipline of clarifying deeply ingrained assumptions, pictures/images that influence employees’ understanding of the world and the actions they take. Change in organizations rarely takes place in the absence of systematic attempts at unearthing these internal pictures, bringing them to surface and holding them rigorously to scrutiny. |

| Systems Thinking | A framework for identifying patterns and inter-relationships, seeing the big picture, avoiding over-simplification, overcoming linear thinking and dealing with issues holistically and comprehensively. |

2.2. Leadership

| Transformational | The leader tries to increase followers’ awareness of what is right and important and to motivate them to perform “beyond expectation.” |

| Idealized Influence (behavior and attributed) is described when a leader is being a role model for his/her followers and encouraging the followers to share common visions and goals by providing a clear vision and a strong sense of purpose. Inspirational Motivation represents behaviors when a leader tries to express the importance of desired goals in simple ways, communicates a high level of expectations and provides followers with work that is meaningful and challenging. Intellectual Stimulation refers to leaders who challenge their followers’ ideas and values for solving problems. Individualized Consideration refers to leaders who spend more time teaching and coaching followers by treating followers on an individual basis. | |

| Transactional | A process that is mainly based on contingent reinforcement. |

| Contingent Reward refers to an exchange of rewards between leaders and followers in which effort is rewarded by providing rewards for good performance or threats and disciplines for poor performance. Management by-Exception (Active) leaders are characterized as monitors who detect mistakes. | |

| Passive-Avoidant | Absent, unavailable leader |

| Management-by-Exception (Passive) leader intervenes with his or her group only when procedures and standards for accomplishing tasks are not met. Laissez-faire or non-leadership exhibits when leaders avoid clarifying expectations, addressing conflicts, and making decisions. |

2.3. Leadership and Learning Organization

2.4. Leadership Outcomes and Learning Organization

3. Hypotheses

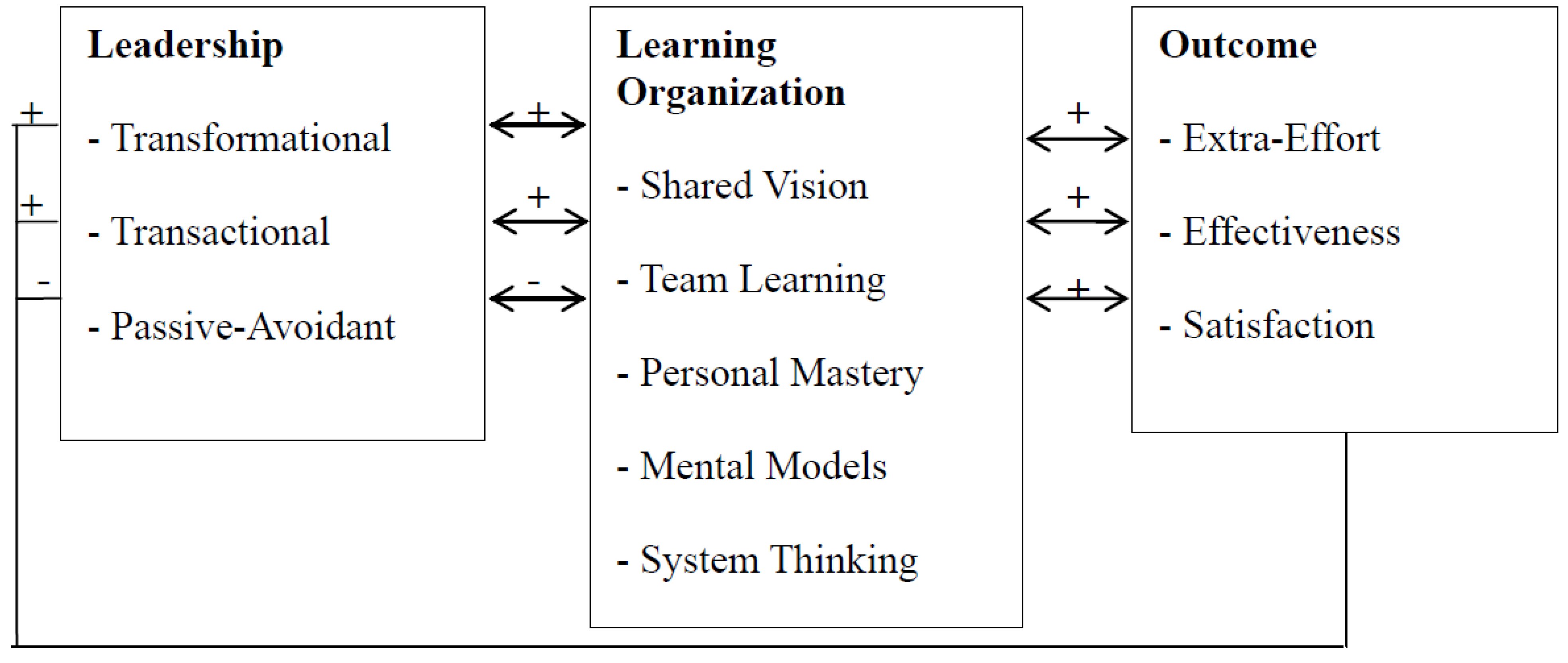

- H1.

- First, we expect Learning Organization characteristics to be positively related to the dimensions of Transformational leadership.

- H2.

- We also expect Learning Organization characteristics to be positively related to Transactional leadership dimensions.

- H3.

- On the contrary, we hypothesize a negative association between Passive-Avoidant leadership and Learning Organization characteristics.

- H4.

- A positive association is expected between Transformational leadership dimensions and leadership outcomes.

- H5.

- Transactional leadership dimensions are expected to have a positive association with leadership outcomes, although to a lesser extent than Transformational leadership.

- H6.

- A negative association is expected between Passive-Avoidant leadership dimensions and outcomes.

- H7.

4. Research Method

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

| Aspects investigated | Dimension | Median (Range) | Percentile * | Scale range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO

Characteristics | Shared Vision | 4.42 (2.3) | 1 to 6 | |

| System Thinking | 4.30 (1.9) | 1 to 6 | ||

| Personal Mastery | 4.67 (1.8) | 1 to 6 | ||

| Team Learning | 4.21 (2.3) | 1 to 6 | ||

| Mental Models | 4.64 (1.8) | 1 to 6 | ||

| Transformational Leadership | Ideal. Infl. (B.) | 3.50 (1.8) | (80) | 0 to 4 |

| Ideal. Infl. (A.) | 2.75 (1.5) | (40) | 0 to 4 | |

| Inspir. Motivat. | 3.00 (1.5) | (50) | 0 to 4 | |

| Intell. Stim. | 3.25 (1.3) | (70) | 0 to 4 | |

| Individ. Consider. | 3.00 (1.5) | (40) | 0 to 4 | |

| Passive-Avoidant

Leadership | Laissez-faire | 0.25 (1.0) | (30) | 0 to 4 |

| Management-by-Exception (Passive) | 1.00 (2.3) | (50) | 0 to 4 | |

| Transactional

Leadership | Management-by-Exception (Active) | 2.00 (2.8) | (70)

| 0 to 4 |

| Contingent Reward | 3.25 (2.5) | (70) | 0 to 4 | |

| Leadership Outcomes | Extra Effort | 3.00 (2.0) | (60) | 0 to 4 |

| Effectiveness | 3.25 (2.3) | (50) | 0 to 4 | |

| Satisfaction | 3.00 (2.0) | (50) | 0 to 4 |

5.2. Correlation Analyses

5.3. Associations between Learning Organization Characteristics and the Dimensions of Transformational Leadership

| Transformational Leadership | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal. Infl. (B.) | Ideal. Infl. (A.) | Inspir. Motivat. | Intell. Stim. | Individ. Consider. | |

| Shared Vision | 0.032 | 0.475 * | 0.048 | 0.025 | 0.287 |

| Systems Thinking | 0.147 | 0.146 | 0.187 | 0.382 * | 0.412 * |

| Personal Mastery | 0.196 | 0.244 | 0.114 | 0.358 | 0.387 * |

| Team Learning | 0.335 | 0.382 * | 0.262 | 0.228 | 0.489 ** |

| Mental Models | 0.229 | 0.480 * | 0.391 * | 0.150 | 0.412 * |

5.4. Associations between Transactional and Passive-Avoidant Leadership and Learning Organization Dimensions

| Transactional Leadership | Passive Avoidant Leadership | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management-by-Exception (Active) | Contingent Reward | Laissez-faire | Management-by-Exception (Passive) | |

| Shared Vision | 0.070 | 0.342 | −0.017 | 0.279 |

| Systems Thinking | −0.087 | 0.329 | −0.234 | 0.086 |

| Personal Mastery | 0.024 | 0.297 | −0.147 | 0.071 |

| Team Learning | −0.031 | 0.424 * | −0.296 | 0.130 |

| Mental Models | −0.157 | 0.321 | −0.217 | −0.008 |

5.5. Associations between Leadership Outcomes, Leadership Dimensions and Learning Organization

| Extra Effort | Effectiveness | Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal. Infl. (B.) | 0.687 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.408 | |

| Ideal. Infl. (A.) | 0.37 | 0.614 ** | 0.271 | |

| Transformational Leadership | Inspir. Motivat. | 0.496 * | 0.407 * | 0.250 |

| Intell. Stim. | 0.376 | 0.305 | 0.458 * | |

| Individ. Consider. | 0.458 * | 0.453 * | 0.207 | |

| Transactional Leadership | Management-by-Exception (Active) | 0.215 | 0.104 | 0.212 |

| Contingent Reward | 0.658 ** | 0.754 ** | 0.443 * | |

| Passive-Avoidant Leadership | Laissez-faire | −0.282 | −0.301 | −0.100 |

| Management-by-Exception (Passive) | 0.272 | 0.104 | 0.181 |

| Extra Effort | Effectiveness | Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared Vision | 0.324 | 0.260 | 0.040 |

| Systems Thinking | 0.328 | 0.255 | 0.080 |

| Personal Mastery | 0.419 * | 0.279 | 0.220 |

| Team Learning | 0.513 ** | 0.327 | −0.029 |

| Mental Model | 0.287 | 0.239 | 0.060 |

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary and Interpretation of Findings

6.2. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DiBella, A.J. Can the army become a learning organization? A question reexamined. Joint Force Q. 2010, 56, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret, J.; Wheatley, G. Can the U.S. Army become a learning organization? J. Qual. Particip. 1994, 17, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gerras, S.J. The Army as a Learning Organization; Army War College: Carlisle, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.D. Is the US Army a Learning Organization? Army War College: Carlisle, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stothard, C.; Talbot, S.; Drobnjak, M.; Fischer, T. Using the DLOQ in a military context: Culture trumps strategy. Adv. Dev. Hum. Res. 2013, 15, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Schiena, R.; Letens, G.; Farris, J.; van Aken, E. Learning Organization in Crisis Environments: Characteristics of Deployed Military Units. In Proceedings of the 2012 Industrial and Systems Engineering Research Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 20–22 May 2012.

- Letens, G.; di Schiena, R.; Farris, J.; van Aken, E. Characteristics of Learning Organization within the Military. In Proceedings of the 2012 American Society of Engineering Management Conference, Virginia Beach, VI, USA, 19–21 October 2012.

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Full Range Leadership Development: Manual for the Multi-Factor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday-Currency: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D.; Khoury, G.; Sahyoun, H. From bureaucratic organizations to learning organizations: An evolutionary roadmap. Learn. Org. 2006, 13, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoghiorghes, C.; Awbrey, S.; Feurig, P. Examining the relationship between learning organizations dimensions and change adaptation, innovation as well as organizational performance. Hum. Res. Dev. Quart. 2005, 16, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recardo, R.; Molloy, K.; Pellegrino, J. How the learning organization manages change. Nat. Product. Rev. 1995, 15, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenjohn, N.; Armstrong, A. Evaluating the structural validity of the multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ), capturing the leadership factors of transformational-transactional leadership. Cont. Manag. Res. 2008, 4, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational Leadership: A Response to Critiques. In Leadership Theory and Research: Perspectives and Directions; Chemers, M.M., Ayman, R., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, Leadership in the Canadian Forces: Doctrine; Canadian Defence Academy: Kingston, Jamaica, 2005.

- Dvir, T.; Eden, D.; Avolio, B.J.; Shamir, B. Impact of transformational leadership on follower development and performance: A field experiment. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.; Arthur, C.A.; Jones, G.; Shariff, A.; Munnoch, K.; Isaacs, I.; Allsopp, A.J. The relationship between transformational leadership behaviors, Psychological, and training outcomes in élite military recruits. Lead. Quart. 2010, 21, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Bass, B.M.; Yammarino, F.J. Adding to contingent-reward behavior: The augmenting effect of charismatic leadership. Group Organ. Stud. 1990, 15, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, T.D.; Tremble, R.T. Transformational leadership effects at different levels of the army. Mil. Psych. 2000, 12, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The leader’s New Work: Building learning organizations. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.; Lee, M. A study on relationship among leadership, organizational culture, the operation of learning organization and employees’ job satisfaction. Learn. Org. 2007, 14, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, R.; Shabbir, M.F.; Shabbir, M.S.; Hafeez, S. The role of leadership in developing an ICT based educational institution into learning organization in Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, D.A.; Edmondson, A.C.; Gino, F. Is yours a learning organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Martinette, C.V. Learning organization and leadership style. 2002; unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P.; Saunders, B. Ten Steps to a Learning Organization, 2nd ed.; Great Oceans Publishers: Arlington, VA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rijal, S. Leadership style and organizational culture in learning organization: A comparative study. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 14, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Nont, S.A. Learning organization as a mediator of leadership style and firms “financial performance”. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, K.E.; Marsick, V.J. Sculpting the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and Science of Systemic Change; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, P. Developing transformational leaders: The full range leadership model in action. Ind. Comm. Train. 2006, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, P.D. Leadership behaviors of principals in inclusive educational settings. J. Educ. 1997, 35, 411–427. [Google Scholar]

- Medley, F.; Larochelle, D.R. Transformational leadership and job satisfaction. Nurs. Manag. 1995, 26, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, K.B.; Kroeck, K.G.; Sivasubramaniam, N. Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. Lead. Quart. 1996, 7, 385–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dum dum, U.R.; Lowe, K.B.; Avolio, B.J. A Meta-Analysis of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Correlates of Effectiveness and Satisfaction: An Update and Extension. In Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead; Avolio, B.J., Yammarino, F.J., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 35–66. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J. Appl. Psych. 2004, 89, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.; Waddell, D. The link between self-managed work teams and learning organizations using performance indicators. Learn. Org. 2004, 11, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishamudin, M.S.; Mohamad Nasir, S.; Shukri, S.Md.; Mohamad Faisol, K.; Mohd Na’eim, A.; Theng Nam, R.Y. Learning organization elements as determinants of organizational performance of non-profit organizations (NPOs) in Singapore. Int. NGO J. 2010, 5, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership and organizational learning. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 222–240. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, T.R. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Avolio, B.J.; Sivasubramaniam, N. Context and leadership: An examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the multi-factor leadership questionnaire (MLQ Form SX). Lead. Quart. 2003, 14, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanste, O.; Miettunen, J.; Kyngäs, H. Psychometric properties of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda, M.J.; Scandura, T.A.; Pillai, R. The MLQ revisited: Psychometric properties and recommendations. Lead. Quart. 2001, 12, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, G.A.; Nelsen, R.B. On the relationship between Spearman’s rho and Kendall’s tau for pairs of continuous random variables. J. Stat. Plan. Infer. 2007, 137, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, R.B. Kendall’s Tau. In Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Supplement III; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 226–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.A. New Measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, J.D. Nonparametric Methods for Quantitative Analysis; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Strahan, R.F. Assessing magnitude of effect from rank-order correlation coefficients. Educ. Psych. Meas. 1983, 42, 763–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, W.L. Statistics for the Social Sciences; Holt, Rinehart, and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, S.; Turvey, C.; Andreasen, N.C. Correlating and predicting psychiatric symptom ratings: Spearman’s rho versus Kendall’s tau correlation. J. Psych. Res. 1999, 33, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Senge’s many faces: Problem or opportunity? Learn. Org. 2007, 14, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsick, V.J.; Watkins, K.E. Demonstrating the value of an organization’s learning culture: The dimensions of learning organizations questionnaire. Adv. Dev. Hum. Res. 2003, 5, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, K.E.; Dirani, K.E. A meta-analysis of the dimensions of a learning organization questionnaire looking across cultures, ranks, and industries. Adv. Dev. Hum. Res. 2013, 15, 2148–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J. Full Range Leadership Development, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Schiena, R.; Letens, G.; Van Aken, E.; Farris, J. Relationship between Leadership and Characteristics of Learning Organizations in Deployed Military Units: An Exploratory Study. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 143-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci3030143

Di Schiena R, Letens G, Van Aken E, Farris J. Relationship between Leadership and Characteristics of Learning Organizations in Deployed Military Units: An Exploratory Study. Administrative Sciences. 2013; 3(3):143-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci3030143

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Schiena, Raffaella, Geert Letens, Eileen Van Aken, and Jennifer Farris. 2013. "Relationship between Leadership and Characteristics of Learning Organizations in Deployed Military Units: An Exploratory Study" Administrative Sciences 3, no. 3: 143-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci3030143

APA StyleDi Schiena, R., Letens, G., Van Aken, E., & Farris, J. (2013). Relationship between Leadership and Characteristics of Learning Organizations in Deployed Military Units: An Exploratory Study. Administrative Sciences, 3(3), 143-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci3030143