1. Introduction

According to data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (

CISE 2018), in Spain in 2017, total entrepreneurial activity (TEA) was 6.2%, below the overall European rate of 8.2%, and much lower than the U.S. rate of 13.6% and the Canadian rate of 18.8%.

In Spain, risk aversion was traditionally three times higher than in the United States; fear of failure was higher; the Spanish did not see themselves as creative; and the media paid insufficient attention to entrepreneurial initiative (

Alemany 2011). These characteristics have improved in recent years. According to the latest GEM (

CISE 2018), risk aversion in Spain is now 10% higher than in the U.S.

From 2011 to the present, as a consequence of the economic crisis, Spain has witnessed a scenario where the national and European public authorities have launched new strategies to mitigate the effects of the recession. In this sense, the European employment and growth strategy (

European Commission 2010) promoted entrepreneurship as one of the primary measures to promote employment and so alleviate the effects of the crisis. Entrepreneurship is considered to be able to generate significant benefits in growth, employment, development and innovation (

Acs et al. 2005;

Gómez et al. 2007;

Nabi et al. 2010;

Oosterbeek et al. 2010).

This concern to promote entrepreneurship also spread to education. The Law for the Improvement of Education (

BOE 2013) included the need to foster entrepreneurial values from the lowest levels of education. At regional level, in Castilla-La Mancha, Law 15/2011 on Entrepreneurs, the Self-employed and SMEs established a series of measures to encourage self-employment. The European authorities have prioritized the integration of entrepreneurship education in primary, secondary and higher education (

Yemini and Haddad 2010). Thus, the university system, as part of its mission to transfer knowledge to companies and society in general, cannot neglect its responsibility to foster entrepreneurship in students and to investigate the profile of the most entrepreneurially-oriented students, to be ready to advise and guide them once they finish their studies so they may find self-employed work as an option to earn a living. Entrepreneurship education at university level may be the key to success in the process of new venture creation (

Barba-Sánchez and Atienza-Sahuquillo 2018;

Hu et al. 2018).

In this context, the University of Castilla-La Mancha is committed to promoting entrepreneurship among students, although it has been doing for a long time through the central unit configured by the Center for Information and Employment Promotion. These activities consisting of encouraging training, guidance and accompaniment of students in the process of job search had not been previously done using actively the figure of the teacher as a dynamic element among students in the promotion of entrepreneurship. This constitutes the main gap that leads us to propose this research.

Thus, in 2016, the University of Castilla-La Mancha, as part of an initiative by the office of the vice-chancellor for transfer and innovation and under the UCLM entrepreneurship program, created the Entrepreneurial Teachers Network (ETN), with the main aim of promoting entrepreneurship in all the disciplines and the degree and post-degree courses delivered at the UCLM, with the support of all the teaching staff involved. The inclusion of teachers from the courses in the project means the content can be personalised in accordance with the professional profiles and competences of each undergraduate degree or master’s program, thus permitting a more intense and effective impact on the students as regards business creation. The ETN has the following objectives: to promote activities in the different faculties that educate and motivate students about entrepreneurship; to support the organization and dissemination of entrepreneurship activities promoted by the office of the vice-chancellor for transfer and innovation; to identify final year projects or master’s theses that should reach a broader public; to identify final year projects or master’s theses that could be implemented as business projects; and to support and supervise student associations that wish to perform activities related to entrepreneurship. More than 70 members of the teaching staff from across the four UCLM campuses participate in the ETN. Since 2016, five training days have been held for academic staff, addressing topics such as diagnosis of entrepreneurship characteristics in students, encouraging creativity, design thinking and the analysis of students’ cross-curricular competences. In 2017, a group of teachers from the ETN worked on a teaching innovation project under the auspices of the office of the vice-chancellor for teaching. Called “Entrepreneurship in Class”, the aim was to determine the profile of UCLM students and to analyse this profile in relation to their intention to create new enterprises as a career opportunity. The ultimate aim of the project is to provide advice to identify, supervise and train potential entrepreneurs, leveraging this potential to generate a vocation for entrepreneurship among young adults in Castilla-La Mancha, thus helping them to create employment.

This initiative demands proactiveness in the sense of searching for students who are inclined towards business creation, and if none are found, they must be mobilised through seminars to raise awareness and stimulate entrepreneurial spirit. Counselling here does not consist of waiting for consultation but of mobilising possible entrepreneurs at an early stage. This means devoting time to studying students’ profiles, contacting them and actively offering them advice on entrepreneurial activities for self-employment or business creation.

Personal counselling is there to provide information related to the situation of the potential beneficiaries of the scheme, generating an individualized diagnosis of each of the users of the guidance service. This diagnosis will lead to an offer of training actions, if necessary, or will go directly to the phase of assisting the students in the procedures to be undertaken in order to start the business venture.

The main aim of this study, apart from presenting the university’s ETN, is to describe the first results obtained through the “Entrepreneurship in the Classroom” Project. These results stem from the proposal of two objectives: on one hand, to analyse the potential profiles that can be determined by the analysis of students’ cross-curricular competences, focusing on entrepreneurship, and, on the other hand to see whether these profiles are related to the intention of creating a business once the students finish their university studies. Thus, we posit two research questions:

RQ1: Are there specific entrepreneurial competences that determine students’ attitude towards entrepreneurship?

RQ2: Do certain competences impact more clearly than others on the intention to create a business in the three years following graduation?

To answer the above research questions, we worked with a sample of 1874 second- and fourth-year undergraduates from the UCLM on degree courses in the arts and humanities, social sciences, engineering and architecture, sciences and health sciences.

The main contribution of this research lies in the realization of a detailed analysis on the degree of development of the entrepreneurship competences of the Castilla-La Mancha students, being able to identify which ones are for them a weakness compared to those in which they are more reinforced. At the same time, this paper contributes to the identification of three competency profiles that characterize these students. On the one hand, we identify a group of competences related to the way of acting that students have, we have identified them as competences related to the “Action”. A second group of competences related to the way in which students relate to others, we have identified them with the “Relationship”. In addition, a third group of skills that have to do with the emotions and emotional control of students, we have identified them as competences related to the “Emotion”. Finally, another of the contributions of this research is to see how these three groups of competences are related to the possibility of created a business venture by students. In this sense, it is concluded that the competences “Relationship” does not influence the intention to create employment, while the way of acting and the emotional state does have a significant influence on said intention.

This work is structured as follows:

Section 1 present a review of the literature.

Section 2 describes the methodology and

Section 3 outlines the results obtained.

Section 4 discusses our findings, the limitations of the study and future research lines. The study closes by presenting our main conclusions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Survey

In the 2017/2018 academic year, a total of 11,982 second- and fourth-year students were enrolled on different degree courses across the UCLM. They were all sent an anonymous on-line questionnaire with a set of 16 questions comprising 35 items intended to measure their entrepreneurial competences. These questions mainly drew on the competences analysed in the REFLEX project (

European Commission 2009). Most of the questions were closed in nature and were rated on a 7-item Likert-type scale.

The sample obtained corresponds to 15.64% of the surveyed population, having received a total of 1874 responses from students enrolled in the second and fourth years of degree courses across the campuses of the UCLM.

Table 1 shows the distribution of students surveyed by campus, year and branch of knowledge.

The analysis concentrated on nine particular competences related to capacities for planning, persuasion, creativity and innovation, teamwork, self-confidence, frustration tolerance, awareness and emotional balance, persistence and proactiveness. Each of these competences was then subdivided into different items, on which each respondent was asked. To facilitate statistical analysis, each of the items was assigned a specific code (see

Table A1).

3.2. Statistical Methodology

First, a descriptive statistical analysis was conducted using the main statistics obtained for each of the items in the questionnaire. The results of this analysis are depicted according to each of the nine competences analysed. An overall analysis was performed on the complete sample and a further segmented analysis was conducted by year group and branch of knowledge.

In order to answer the first of our research questions (RQ1), which aims to identify the specific profiles that enable the entrepreneurial competences to be described, we conducted a factor analysis to identify the items analysed according to particular factors. Each of these factors corresponds to a specific profile including competences that refer to concrete capacities of the students. Before applying the factor analysis, we verified the fit of this methodology to our sample. Although there is some debate on the sample size required to apply this analysis, according to (

Beavers et al. 2013) and (

Sánchez-Villegas et al. 2014), the sample analysed is at level 5 of 6, and can thus be considered highly appropriate for factor analysis. The correlation matrix obtained shows a high level of correlation between the variables and with the factor or factors obtained. The method of extraction used was principal component analysis.

Once the factors had been identified, it was necessary to determine the number of factors to conserve, for which there are various norms and criteria. Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a chi-square value of 0.45 with a p value of 0.000, meaning the null hypothesis of non-correlation between variables was rejected. These aspects are usually checked by applying the KMO test of sampling adequacy, which must yield a value between 0 and 1. Low measures (less than 0.5) show that factor analysis is unadvisable, given that the correlations between pairs of variables cannot be explained by other variables. A value close to 1 indicates that the data are fully adequate for a model of factor analysis is obtained. In our study, the KMO statistic was 0.904. The scree plot shows the factors obtained, distinguishing between those that explain a large part of the variance and those that do not.

Finally, in order to answer the second of the research questions (RQ2), which considers the relationship between the entrepreneurial competences identified in the previously defined factors and the students’ intention to create a business venture in the three years following their graduation, we applied the analysis derived from the binary linear regression, in which our dependent variable was the dichotomous variable of “intention to create a business” with values of “0 = No” y “1 = Yes”. The factors obtained from the application of the factor analysis were taken as the independent variables. The significance of the chi-square model was less than 0.05, which indicates the model helps to explain the event; in other words, the independent variables explain the dependent variable. The overall predicted percentage is 87.7%, suggesting the number of cases the model is able to correctly predict; with a value of over 50% the model is considered acceptable.

Although the values of Cox and Snell’s R squared and Nagelkerke’s R squared explain no more than 3% of the model, and knowing that these statistics frequently yield low values, the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test reflects whether the linear regression model fits well to the data, by means of the following hypotheses: H0: “the model fits well” vs. H1: “the model does not fit well”. If the result of the test is significant (p < 0.10), none of the calculations are valid. In our case, p = 0.256, and thus it can be said that the model is adequate for a 95% confidence interval.

All our analyses were conducted using SPSS V.24.0, 2018.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Descriptive Analysis

Table A2 (

Appendix A) shows the values for the main descriptive statistics in our study. Among the highest rated items, we find the ability to express points of view and stand by a position, taking responsibility for the outcomes of actions and complying with commitments despite having to make sacrifices. Among the lowest rated items setting dates to complete tasks and keeping to these dates, fostering a climate which facilitates the circulation of information and mutual trust and facilitating a climate of open communication, motivating and encouraging the members of the team.

Below,

Table 2 shows the aggregate results obtained for each of the new competences under study, divided by year group and branch of knowledge.

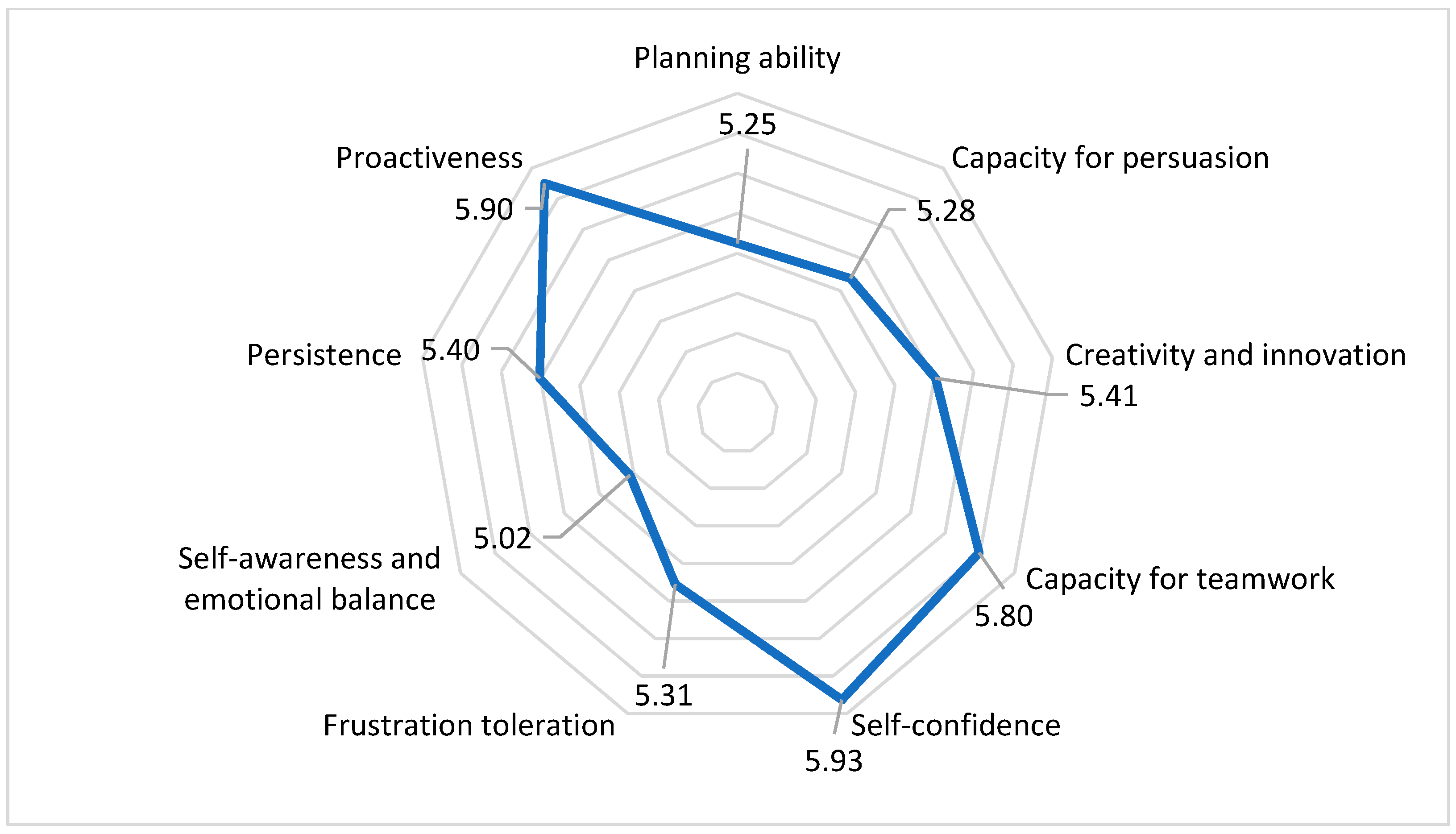

In general,

Figure 1 shows the assessment that students make about their competences. In this sense, the competence related to self-awareness and emotional balance reaches the lowest values (mean = 5.02), being therefore the competence in which the students are less prepared with regard to stress management, the way they respond to unexpected situations, the management of fear of failure or the assumption of risks. Regarding the competence for which the students are better prepared, the self-confidence stands out (mean = 5.93). In this sense, students are in accordance with their ability to work autonomously and to remain firm in their positions.

Both in

Table 2 and

Figure 2 can be observed in the same way that the self-awareness and emotional balance and self-confidence are the least and most valued competences, respectively, by the students classified according to the year group. However, the values of all the competences for the fourth-year students are higher than the values obtained for the second-year students. This leads us to think of a greater maturity of the fourth-year student, who sees his exit to the working market soon, better prepared in competences towards entrepreneurship. This improvement can be the result of the actions for the promotion of entrepreneurial skills that are carried out in the university and that are focused with greater emphasis on students who are close to finishing their undergraduate studies.

Table 2 shows the results according to the area of knowledge. It can be observed that the self-awareness and emotional balance is the competence least valued by students of all branches of knowledge. Of all of them, Science students have the lowest values (mean = 4.87). Regarding the best-valued competence, the self-confidence is valued in all branches, with Arts and Humanities students who value this competence better (mean = 6.17). Students of Social Sciences are considered better prepared in Proactivity (mean = 5.94). This last competence is also valued by Science students.

4.2. Factor Analysis Results

Further to the descriptive analysis within each dimension, we conducted a factor analysis taking into account the 35 items included in nine competences, in order to identify the profiles related to cross-curricular skills that might characterise students when conducting entrepreneurial activities. This statistical technique yielded six factors which, overall, explained 59.49% of the variance, with the first factor explaining almost 36%. The analysis of these factors did not suggest that the competences grouped under a single factor might define a specific entrepreneurial behaviour as most of the items were located in the first factor.

Table A12,

Table A13 and

Table A14 (

Appendix A) present the results of this first factor analysis, showing the distribution of commonalities, the explanation of variance and the component matrix by each factor.

Figure 3 presents the scree plot of the six factors. Although the KMO statistic is almost 95% and the results of Bartlett’s test are significant, we believe this analysis does not permit any conclusions to be drawn. The explanation of the items is mainly to be found in the first component and hence no valid conclusion can be made. The same result was found when the maximum number of factors was reduced to three.

The scree plot of the three factors is shown in

Figure 3.

This analysis served to select 15 items from the original 35 in order to repeat the factor analysis. Thus, from the table of commonalities obtained using all 35 items, we selected the 15 factors that had the largest effect in the sample, selecting those with the greatest impact and with the condition that at least one item was included from each competence.

Table A12 shows these items, being PL2, PER2, CI1, CI2, CTW2, CTW4, SC2, FT2, SAEB1, SAEB2, SAEB4, PST1, PST2, CPRO1 and PRO4.

Table 3 shows the total explained variance of 57.92% and the extraction of three factors identified in the rotated component matrix from

Table 4.

The three factors can be defined as follows:

Factor 1 “ACTION”: This factor includes the factors related to task performance and effectiveness in management and actions. The following items were identified:

I foresee the resources needed to perform my tasks

I can find solutions to complex problems

I can bring together different ideas to generate new ones and solutions to problems

I am able to work independently

I develop and execute action plans until I reach the expected outcomes

I take control of my work efficiently

I seek opportunities and take initiatives to turn opportunities into results

Factor 2 “EMOTION”: This factor included competences related to management of uncertainty and emotional control. It comprises the following items:

I am able to redirect and take the positives from an unexpected situation

I am able to cope with stress and maintain my emotional balance in critical situations

I am able to identify my emotional state and adapt it to particular contexts

I can manage my fear of failure, seeing situations as learning opportunities

Factor 3 “RELATIONSHIPS”: This factor includes competences related to leadership and teamwork. It includes the following items:

I visualise and easily manage key points in negotiations with my colleagues

I am open to suggestions and proposals from the team

I facilitate a climate of open communication, motivating and encouraging the members of my team

Based on this factor analysis, we grouped the 15 items under three factors identified with groups of competences. We called the first factor “ACTION”. It explains 40.8% of the variance and encompasses students who consider that competences associated with planning, execution, problem-solving and management of actions are determinants when undertaking entrepreneurial activity. The items with the greatest weight in this factor are the ability to work independently and taking control of work efficiently.

The second factor, “EMOTION”, explains 9.41% of the variance and includes the competences associated with risk management and emotional control. The items with the greatest impact in this factor are being able to cope with stress and maintain one’s emotional balance in critical situations and being able to identify one’s emotional state and adapt it to particular contexts.

The third factor, “RELATIONSHIPS”, explains 7.6% of the variance and included competences connected with teamwork. The most representative item in this factor are delegating and supporting without generating conflicts or rivalries and facilitating a climate of open communication, motivating and encouraging the members of the team.

These findings mean we can answer the first research question (RQ1), as we have identified three groups of entrepreneurial competences at the university, where the most important group is that based on individual competences associated with working independently and problem solving.

4.3. Results of the Binary Logistic Regression

The results of the binary logistic regression, which analyses the relationship between the dependent variable of “intention to create a company” and the independent variables represented by the three factors identified in the previous section, are presented according to two steps. In Step 0, the variables are not included and in Step 1, they are. The results of these two steps are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6, respectively.

It can be seen that the profiles related to efficient management and action and risk management and emotional control are significant factors. However, while ACTION is positively associated with the intention to create a company in the three years after graduation, for EMOTION this association is negative. In other words, the higher the score on emotion, the lower is the intention to start an enterprise in the next three years. ACTION is the variable that most influences the intention to start a company (Exp [B] de 1362), while “RELATIONSHIPS” has no significant impact on the intention of starting an enterprise in the three years following graduation.

Thus, in response to Research Question (RQ2), we can say that the competences related to planning, management and control of activities are positively related to the intention to create a company, while the competences associated with emotional control and risk management are negatively related to entrepreneurial intention.

5. Discussion

The descriptive analysis of competences shows that self-confidence and proactiveness are the competences most highly rated by students. This is consistent with the studies by (

DeTienne and Chandler 2004) and (

Muñoz and Martínez 2011), who highlighted the importance given to taking responsibility for the outcomes of actions and following through with commitments despite having to make sacrifices. The students in the sample also consider themselves ready to work independently, in line with the findings of (

Robinson et al. 1991).

With regard to the competences the students consider less important, we find the capacity for self-awareness and emotional balance. This is in line with (

Gibb 1987), who presented similar findings on the capacity to manage fear of failure and see situations as learning opportunities and the ability to cope with stress and maintain emotional balance in the face of critical situations. In contrast, (

Allison et al. 2000) found that this item was considered one of the most important to define students’ entrepreneurial behaviour. Furthermore, in the same line as (

Brettel et al. 2015), the students at UCLM do not consider among the most important competences that of setting a date to complete a tasks and keeping to it. Students also consider capacity for persuasion to be one of the most difficult competences to achieve.

The fourth-year students scored all items higher than their second-year counterparts did. This supports the idea, in coherence with (

Gibb 2002) and (

Lazear 2004), of the effectiveness of the process of education in entrepreneurship at universities. Both fourth- and second-year students attach greater importance to self-confidence and proactiveness and less importance to self-awareness and emotional balance and capacity for persuasion. However, the fourth-year students feel themselves to be better prepared in competences related to teamwork, planning, persistence and creativity than those in the second year.

As regards the analysis by branches of knowledge, students of arts and humanities and health sciences are those who better prepared in planning skills, while those who study engineering and architecture and health sciences score themselves highest on the capacity for persuasion. The students of engineering and architecture and arts and humanities scored highest on creativity and innovation. Arts and humanities students scored highest on persuasion. Students enrolled on health science degrees scored highest on self-confidence and persistence. Engineering and architecture students ranked highest on self-awareness and emotional balance and frustration tolerance. Finally, social science students considered themselves the most proactive.

With respect to the relationship between the above factors and the entrepreneurial intention of business creation as an employment opportunity and as an answer to RQ2, this work shows a positive relationship between the option of a business venture and the factor linked to action and efficiency in management and activities. This coincides with the findings of (

Hong and Yang 2014). Our study also underlines a negative relationship between the intention of business creation and competences linked to the management of uncertainty and emotional balance, which coincides with the findings of (

Souitaris et al. 2007). No relationship was found between the third factor referring to teamwork competences and entrepreneurial intention, coinciding with the work by (

Oosterbeek et al. 2010).

With regard to the limitations of this work, while also indicating an objective for future lines of research, we can mention the fact that the study focuses on a survey with only one moment of data collection, that of the 2017/2018 academic year. This rendered it impossible to conduct a longitudinal analysis, and hence, our aim is to repeat the survey in the second semester of the 2018/2019 academic year, working again with students enrolled in the second and fourth years of degree courses at the UCLM. Moreover, we consider it necessary to delve deeper into the relationship between competences and entrepreneurial outcomes, defining student profiles by means of cluster analysis including other outcome variables.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to highlight the role of higher education in generating entrepreneurial competences. To this end, the UCLM created the entrepreneurial teachers network (ETN) in 2016 with the aim of promoting entrepreneurship in the university’s students and analysing their entrepreneurial competences. It is also intended to deliver training oriented towards entrepreneurial activity for both students and the teaching staff involved in the ETN, in order to detect weaknesses and bolster the strengths identified in the profile of our students’ entrepreneurial competences.

The study presents an analysis of the students’ perception of nine competences examined across 35 items, having administered the same overall survey to second- and fourth-year students, but differentiating between year group and branch of knowledge. The fact that the students in the fourth year rate their entrepreneurial competences higher compared to those in the second year supports the notion that the entrepreneurship education delivered at the UCLM may be having a positive effect in improving the education of students in this field.

Three different factors were identified. The factor with the highest impact was found to be that comprising foreseeing the resources needed to perform tasks, the ability to find solutions to complex problems, the ability to bring together ideas to generate new ideas and solutions to problems, the ability to work independently, developing and executing action plans until the expected outcome is reached, efficient task management and the search for opportunities and the adoption of initiatives to turn such opportunities into results.

Finally, we examined the relationship between these factors and students’ intention to create a business venture after finishing their degree, leveraging entrepreneurial intention as an employment opportunity. A significant positive relation was found between entrepreneurial intention and the highest evaluated factor, that of efficiency in management and actions, while a negative relationship was found between such intention and the lowest rated factor of emotion management and emotional balance. No relationship was found between business incubation intention in the three years following graduation and the capacity for collaborative teamwork.

To conclude, we explicitly highlight the implications that the results of this research can have both at a practical and at a theoretical level. On the one hand, the conclusions obtained in relation to the study of transversal competences of students will allow the University to define its policy of action in relation to the promotion of entrepreneurship. As a result, those competences in which students are less prepared will be reinforced and the University could act on those that may have the greatest influence on the intention to create a business venture when students finish their university studies. Undoubtedly, these actions carried out by the University, through the teachers, will imply the adjustment of the teaching methodologies and the complementary training to be able to contribute to the identification of the most entrepreneurial profiles within the classroom.

On the other hand, the creation of working groups such as the Entrepreneurial Teachers Network (ETN) of the University of Castilla-La Mancha, will revert in the benefit of the students. More enterprising students who will create their own company or students who, working as an employee, will develop entrepreneurial activities in the organization for which they are working. In this case, we are talking about the concept of “intrapreneur”. All of this, without a doubt, will finally revert to a benefit for society that will have better prepared entrepreneurs, professionals and employees.