1. Introduction

Sugarcane belongs to a restrict group of agricultural crops considered dominant, which, together with cotton, soy, corn, wheat, and rice, occupies millions of hectares of land [

1,

2,

3]. In addition to countries where the species originates, the main producers are Southeast Asian countries, particularly the Philippines, Thailand, India, and Brazil, which have assumed global dominance concerning the area dedicated to production and yield per hectare achieved [

4,

5,

6]. In fact, according to the information provided in 2020 by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), there is currently an annual production of 1.89 billion tons, occupying a production area of 27,000,000 hectares spread over more than 100 countries. As can be seen in

Table 1, the 20 largest world producers represent a production of 1.75 billion tons per year in an area of approximately 24,250,000 hectares, completely dominating the sector with 93% of world production in 91% of the total area occupied by sugarcane. In addition to being a food crop, sugarcane can also be considered an energy crop, since ethanol is produced from sugar. In this regard, Brazil is considered as a pioneer, mainly due to the developments achieved from the 1970s after the oil crisis [

7,

8,

9,

10].

The reality of sugarcane production in European countries is different from that in major production countries such as Brazil, India, the United States, and the Caribbean region [

13,

14,

15,

16]. In reality, production in Portugal, Spain, and Italy occurs in isolated regions, namely, in the island regions of Madeira, the Canaries, and Sicily, where sugarcane production was introduced as a subsistence culture to support colonization efforts centuries ago [

17,

18,

19].

In Portugal, according to the official website of the Institute of Wine, Embroidery, and Handicrafts of Madeira (

http://ivbam.gov-madeira.pt/cana-de-acucar-1316.aspx), sugarcane was introduced in 1425, imported from Sicily by order of D. Henrique shortly after the beginning of its colonization. The adaptability of this crop in terms of survival compared to others made it a vector for the creation of wealth [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In 1882, sugarcane was attacked by pests and almost disappeared completely in 1884, 1885, and 1886. The introduction of new varieties made it possible to rebuild the cane fields that, from 1890 onwards, expanded again, feeding the sugar industry and the manufacture of rum and alcohol on the island [

24]. For farmers, sugarcane also had the advantage of having a remarkable double aptitude: it can also be used as fodder, as its leaves are rich in nutrients for animal feed [

25]. This occurred at a time when the dairy industry was growing in Madeira [

26]. At the end of the 1930s, sugarcane, which occupied an area of 6500 hectares, was reduced due to the delimitation of agrarian areas to an estimated total area of 1420 hectares in 1952 [

27]. The average production in 1952 was considered to be limited to 30 tons per hectare. From 1952 onwards, the areas expanded a little more, and in 1955–1956, there was an appreciable increase in plantation. Until the end of the 1980s, there was a substantial decrease in the cultivation area related to the closure of several industrial units of great importance [

20]. This has led to a collapse in the crop due to the lack of outlets, with the crop limited to just over 100 hectares (in 1986, it was 119.9 hectares, and it rapidly decreased to 90.3 hectares in 1988). In addition, farmers began to have other crops, such as bananas, vegetables, tropical and subtropical fruit trees, and vines, among others [

26]. Currently, the area is around 172 hectares, which corresponds to a production of 10,830 tons. Productivity still varies, ranging from 40 t/ha in old cane fields to 120 t/ha in more recently installed cane fields. In terms of area, the most important municipalities are Ponta do Sol and Machico (with relative importance levels of 29 and 28%, respectively), followed by Santana (14%) and Calheta (8%), totaling 79% of the area of influence [

28,

29].

From this agricultural production, in addition to the main material, sugar, there are some by-products that are of interest for recovery. Of these, sugarcane bagasse stands out as a product with strong potential for energy recovery, since it is a renewable biological material that, if properly processed and densified, can be used an alternative source of carbon-neutral renewable energy [

30,

31,

32]. Sugarcane bagasse is commonly used for the generation of steam in sugar plants and in the distillation of alcohol. In Brazil during the 1970s, Pro-Alcohol was the first major program to replace fossil fuel with a renewable fuel, hydrated ethanol [

33,

34,

35]. At that time, bagasse was considered waste, and similar to any waste, it was necessary to discard it [

36]. Burning or incineration in a boiler was a means to dispose this waste, generating part of the energy consumed at production plants [

37]. Thus, over the years, bagasse has gone from a waste product to a relevant source of energy, and with each passing day, its importance increases proportionally to the evolution of energy prices in the international market [

38]. Thus, this by-product is no longer considered a waste product and has become an important type of energy input [

39]. Sugarcane bagasse presents great potential for the production of derived fuels using gasification, rapid pyrolysis, or hydrolysis followed by fermentation [

40]. For further development of these technologies, detailed knowledge of the physical and chemical characteristics of sugarcane bagasse is necessary [

41].

Sugarcane bagasse is also used in the pulp and paper industry, as documented in several studies, such as those presented by Samariha and Khakifirooz (2011) investigating the production of pulp from bagasse for the manufacture of corrugated board [

42], the work of Lois-Correa (2012) studying the correlation between bagasse fiber quality and its influence on the final quality of the paper produced [

43], and the research conducted by Hemmasi et al. (2011) analyzing the chemical and anatomical properties of sugarcane bagasse used in paper production [

44]. However, as described in the referred works, it can be concluded that sugarcane bagasse presents a set of limitations—for example, its low bulk density and high moisture content, and the speed with which it starts its biological degradation process, similar to those identified in cereal straw, although it offers greater versatility [

45].

This work aims to characterize the use of sugarcane bagasse for energy generation in a way that allows both its storage and the possibility of exporting it as an energy product due to the energy densification process using a thermochemical conversion process. To carry out this work, a bibliographical review of the processing of sugarcane bagasse was prepared when the sugarcane samples were acquired, which were characterized and subjected to the thermochemical conversion process of torrefaction as a way to achieve preservation for long periods of time, allowing safer storage without biological activity and becoming hydrophobic. These new thermally treated and energy densified products can be transported, offsetting the logistical problems associated with high transportation costs. As a result, the main parameters for the use of sugarcane bagasse as an energy source were identified. This review and analytical study brings together data obtained by previous research works in order to present and consolidate important information related to the physical and chemical characterization of sugarcane bagasse for energy purposes, as well as to compare the results obtained by the characterization, in order to indicate another option for creating a potential value chain for the energy recovery of this product.

2. Raw Material Characterization

Sugarcane bagasse is the solid residue produced in sugar mills after the extraction of juice, and over the years, it has become an important energy input [

46]. Thus, it is necessary to know its characteristics in order to use it efficiently with adequate drying performance for the generation of steam, pyrolysis, or gasification, or for hydrolysis [

47]. Sugarcane,

Saccharum officinarum L. (Poaceae), has been known since 8000 BC and is one of six species of the genus

Saccharum, which is a group of tall grasses from Southeast Asia. The stems are the parts from which sugar juice and bagasse are produced [

46]. However, leaves and other parts can also play an important role in the generation of energy, mainly in co-generation systems, as described by Sampaio et al. (2019) [

48]. The composition of sugarcane is approximately 86 to 92% juice and 8 to 14% fibrous material [

46]. This depends not only on the composition of stems, but also on other factors, such as the plant variety, number of tips and leaves, maturation, harvesting period, whether it was burned or not before harvesting, whether the harvest was mechanized or manual, and climatic factors such as whether it rained or not during the plant growth period [

49]. Physical and chemical characteristics of sugarcane bagasse have a direct influence on its use as an energy source. The commonly used method is bagasse combustion in steam generators, and knowledge of bagasse characteristics is necessary for the design of steam generation equipment [

46].

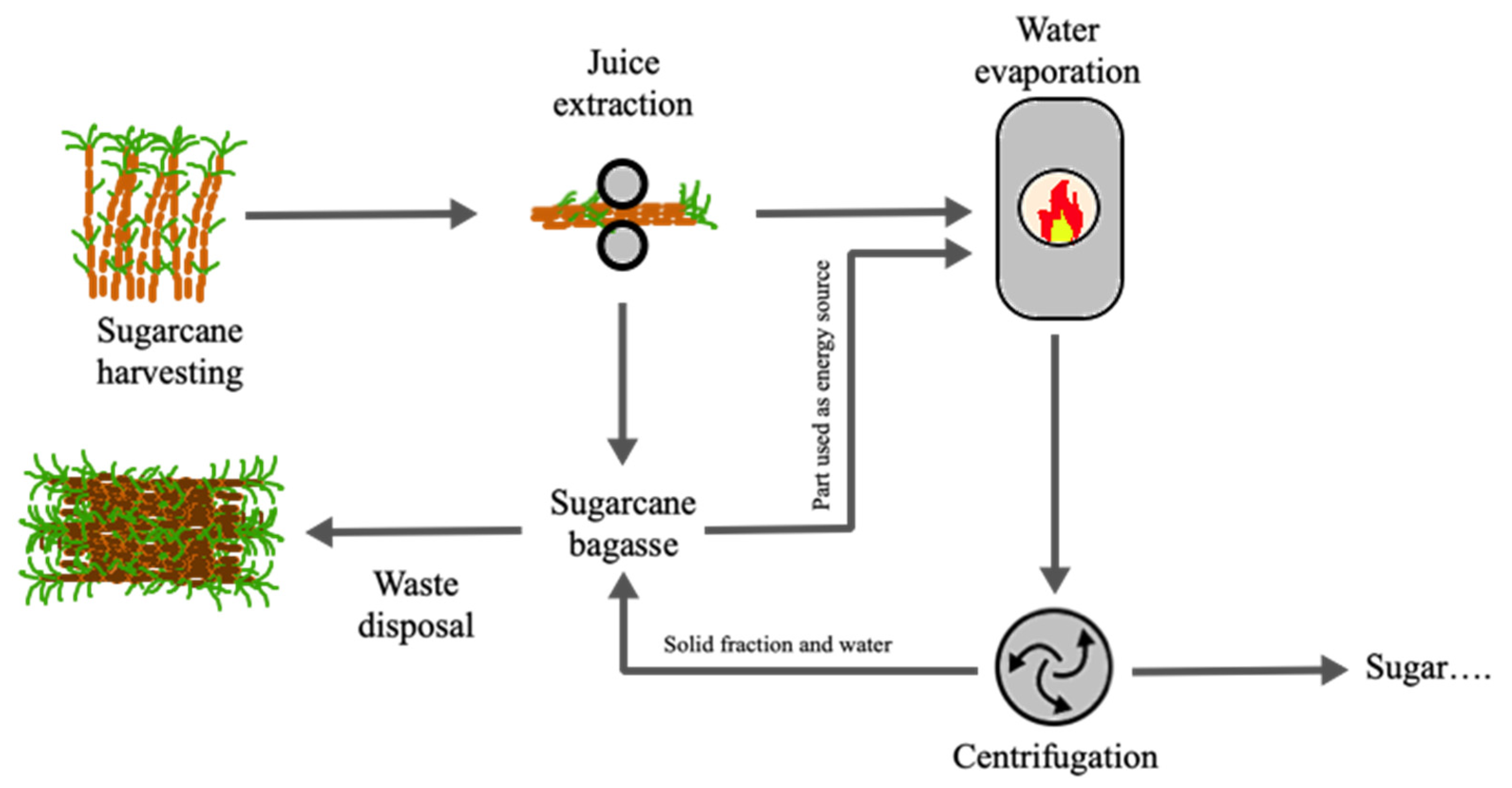

Figure 1 shows a scheme of the sugar and sugarcane bagasse production process. As can be seen from the process diagram shown in the figure, after cutting the sugarcane, the materials are successively processed through a set of roller mills, where the cane juice is extracted. This juice subsequently undergoes an evaporation process in order to eliminate excess water and concentrate the sugar. In the end, the juice also undergoes a centrifugation process to eliminate all remaining water and any solid particles, namely fibrous remains of the cane. After the pressing process by the roller mills, the sugarcane gives way to bagasse. This is partly consumed to feed the furnace that provides the heat for the evaporation of water from the cane juice, while another part is left over as final waste [

50].

Sugarcane bagasse is a complex mixture of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which make up the cells of the walls in vascular bundles [

51]. The amount of fiber in the stems depends on the length and diameter of the stems. The number of nodes and the distance between nodes influence the amount of fiber obtained in the extraction [

46]. Cellulose is a high-molecular-weight polymer composed largely of glucose units. Hemicellulose is largely composed of xylose units with small parts of arabinose, both with five carbons in the molecular structure (pentose), as opposed to glucose, which has six carbons in its molecular structure (hexose). Lignin is a complex substance composed largely of aromatic phenolic compounds that generally give the sugarcane fiber its stiffness [

52,

53,

54]. The relative amounts of these compounds depend on the variety of the cane, the age, and the size of the stems. There are also small amounts of inorganic compounds, such as calcium and silica, present in the cellular structures, but these do not have a significant effect on the overall fiber composition [

55]. Ash is an inorganic compound found in the bagasse structure, and its composition depends on the plant species, soil, type of fertilization, and inorganic materials dragged during harvesting, which can be mechanized or manual. The main elements are silica, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and other inorganics [

56,

57,

58].

In a study, de Moraes Rocha et al. (2015) collected 60 samples of sugarcane bagasse from industrial sugar and alcohol production units located in São Paulo and northeastern Brazil [

60]. These bagasse samples were selected to include different varieties of sugarcane, and to be representative of the types of soils and climates in different geographical regions and with different harvesting methods. It is a common practice to plant mixed varieties of sugarcane, which grow side-by-side and are harvested simultaneously, as a way to avoid the proliferation of pests. Collected samples were later ground and analyzed in the laboratory.

Table 1 shows the results obtained for all samples, summarizing the representative composition of sugarcane, as well as the results obtained in a previous study conducted by Triana et al. (1990). As can be seen from the results, sugarcane bagasse is, on average, made up of 42.2% cellulose, 27.6% hemicellulose, 21.6% lignin, 5.63% extractive compounds, and 2.84% ash, with a standard deviation of 1.93, 0.88, 1.67, 2.31, and 1.22, and a coefficient of variation of 4.6, 3.2, 7.7, 41.0, and 43.0, respectively. As can also be inferred from the statistical analysis presented in

Table 2, in general, the composition of main components did not differ significantly between samples. These results are in line with previous studies by the same authors [

61,

62], but also with other studies [

55]. They are also in agreement with those presented by Triana et al. (1990), who classified the average values as being in the range of 40% to 50% for cellulose, 25% to 30% for hemicellulose, and 20% to 25% for lignin [

63]. The extractables and ash content obtained in the study show a dispersion trend, which is justified by the fact that these parameters are dependent on the conditions where the plants grow [

60].

4. Results

The results obtained in the laboratory analysis are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 for the dried samples, samples processed at 200 °C, and samples processed at 300 °C, respectively. All analyses were conducted in triplicate, and average values and standard deviation for all tests and calculations were determined.

Table 4 presents the results obtained for samples after drying. As can be seen in the results of elementary analysis, the average values obtained for carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen were 47.40%, 6.59%, 0.11%, and 45.99%, with standard deviations of 0.58, 0.39, 0.02, and 0.53, respectively. Thermogravimetric analysis gave mean values for fixed carbon, volatiles, ash, and moisture of 16.38%, 81.25%, 1.36%, and 3.31%, with standard deviations of 0.13, 1.30, 0.10, and 0.51, respectively. The HHV, calculated using Equation (2), presented an average value of 18.17 MJ·kg

−1 with a standard deviation of 0.55.

Table 5 presents the results obtained for the samples after thermal treatment at 200 °C. As can be seen in the results of elementary analysis, average values obtained for carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen were 53.16%, 6.44%, 0.12%, and 40.28%, with standard deviations of 2.42, 0.19, 0.01, and 2.32, respectively. Thermogravimetric analysis gave mean values for fixed carbon, volatiles, ash, and moisture of 20.79%, 77.74%, 1.48%, and 1.03%, with standard deviations of 0.60, 1.35, 0.38, and 0.22, respectively. The HHV, calculated using Equation (2), presented an average value of 20.75 MJ·kg

−1 with a standard deviation of 1.03. The average weight of samples used in this test at 200 °C was 505.83 g, with a standard deviation of 3.85, and the average weight of samples after the test was 415.62 g, with a standard deviation of 5.17. This difference indicates an average loss of mass of 17.83%, with a standard deviation of 1.21. The calculation of EDR, MY, and EY presented average values of 1.14%, 82.17%, and 93.95%, with standard deviations of 0.08, 1.21, and 5.84, respectively.

Table 6 presents the results obtained for the samples after thermal treatment at 300 °C, according to the procedure presented in

Section 3.2. As can be seen in the results of the elementary analysis, the average values obtained for carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen were 78.61%, 6.54%, 0.43%, and 14.42%, to standard deviations of 1.21, 0.14, 0.04, and 1.15, respectively. Thermogravimetric analysis gave mean values for fixed carbon, volatiles, ash, and moisture of 68.52%, 27.10%, 4.39%, and 3.79%, with standard deviations of 1.56, 1.90, 0.37, and 0.30, respectively. The HHV, calculated using Equation (2), presented an average value of 33.36 MJ·kg

−1, to a standard deviation of 0.47. The average weight of the samples used in this test at 300 °C was 507.86 g, with a standard deviation of 4.60, and the average weight after the test was 156.45 g, with a standard deviation of 4.99. This difference indicates an average loss of mass of 69.20%, with a standard deviation of 0.77. The calculation of EDR, MY, and EY presented average values of 1.84%, 30.80%, and 56.69%, with standard deviations of 0.08, 0.77, and 3.80, respectively.

5. Discussion

Biomass has lower density, higher moisture content, and lower heating value compared with fossil fuels [

68]. The diversity of sources and seasonality of some raw materials introduce challenges related to logistics that hinder their use on a larger scale [

69]. In an attempt to address these drawbacks, we need to homogenize raw materials in order to produce more energy-dense fuel [

70].

Torrefaction is a process that subjects materials to temperatures from 220 to 320 °C in the absence of oxygen [

71]. The thermal decomposition of biomass begins with the evaporation of water and extractives up to 150 °C. Between 150 and 220 °C, there is a slow process of depolymerization of hemicellulose with the emission of certain lipophilic compounds, and the material starts to show structural deformity in the plant tissue [

72]. Between 220 and 320 °C, torrefaction is carried out, involving the volatilization of hemicellulose and depolymerization and partial volatilization of lignin and cellulose [

73]. The release of hydrophilic extractives such as oxygenated compounds, carboxylic acids with high molecular weight, alcohols, and aldehydes, among other gases, with the complete destruction of the plant cell structure, results in a more brittle material [

74]. Above 300 °C, the other compounds present in the biomass volatilize, resulting in the beginning of the pyrolysis process [

75].

In general, the composition of torrefied biomass shows an increase in the fixed carbon content as torrefaction severity increases [

76]. Since it has a lower O/C due to the volatilization and transformation of chemical components, the proportion of carbon in the elemental chemical composition is increased, and this directly contributes to the increased heating value [

77].

The ultimate analysis of a fuel characterizes its chemical composition in terms of its main chemical elements, which are normally represented by C, H, O, and N. The performance of biomass as a fuel is directly related to its chemical composition. The work of de Moraes Rocha et al. (2015) presented the results of the ultimate analysis of 60 samples of sugarcane bagasse, of which the average values are shown in

Table 7 [

60].

Table 7 shows that the carbon content of biomass is about 45%, with a standard deviation of 1.1%. This deviation is acceptable considering the heterogeneity of the sample and the final objective of this material: thermal conversion. According to the results presented in

Table 7, these samples had an average carbon/hydrogen ratio of 7:1, an average carbon/oxygen ratio of 1:1, an average carbon/nitrogen ratio of 166:1, and an average oxygen/hydrogen ratio of 8:1 [

60]. The decreased atomic ratios of O/C and H/C in relation to untreated biomass make it possible to compare the characteristics of torrefaction biomass with other solid fuels, such as mineral coal and charcoal, using the Van Krevelen diagram (

Figure 5). Calculating the H/C and O/C ratios for the analyzed samples, the results shown in

Table 8 were obtained; then, they were projected onto the Van Krevelen diagram shown in

Figure 5. The black dots represent the analyzed samples. As can be seen, although one of the samples, produced at 200 °C, already had a higher HHV, it was still projected into the area of untreated biomass, indicating good potential performance with increased temperature, as seen with the heat-treated samples at 300 °C, which were projected into an area corresponding to bituminous coal.

When evaluating the use of torrefied biomass as raw material for other thermochemical conversion processes, it was found that for combustion reactions, the solid product can be used as an industrial fuel in boilers for steam production and in co-combustion with mineral coal. In addition, the possibility of storing it for long periods can also facilitate its domestic use [

79,

80]. In the literature, torrefaction followed by densification has been reported. Densification is a compaction process that uses equipment such as presses or extruders to increase the durability and improve the physical characteristics of biomass residues [

81,

82,

83,

84]. In the case of torrefaction, it is possible to densify the material by briquetting or pelletizing in order to obtain a final product with greater hydrophobic character and high physical and energetic density [

85,

86]. With this, the material can have standard sizes that favor transportation, storage, and handling, as well as facilitate the feeding of raw materials in industrial and domestic installations [

78]. Apparently, for the lowest temperature used in this test, 200 °C, there should be no problems during densification, since even the color of the material is still light to dark brown and not black, as seen in samples treated at lower temperatures. Most likely, the state of lignin and cellulose did not change during the test at 200 °C, but it most certainly did at 300 °C, making it more difficult without the use of binders.

The heating value tends to be higher for torrefied biomass than non-torrefied biomass. However, in contrast to this increase, there is mass loss of the material, as seen in

Table 8, and the need to obtain a mass and energy balance to verify the technical–economic application of the thermochemical conversion process to check its feasibility is evident.

From the thermogravimetric analysis, it can be inferred that there is an increased concentration of fixed carbon, which is associated with the loss of hydrogenated compounds, in line with the results presented in the work of Quiroga et al. (2020) [

87]. The moisture content decreases from an average value of 3.31% for dry material to an average of 1.03% in material processed at 200 °C. This follows the normal trend, since it is a process of forced drying of nonstructural water, but it is still present in the material. However, when assessing the moisture content of materials processed at 300 °C, it appears that it rises again to 3.79%. This rise should be associated with the release of water contained in the material structure and/or the release of hydroxyl radicals, as was portrayed in the work of Chew and Doshi (2011) [

88].

The results presented in

Table 5 indicate that a simple heat treatment at 200 °C leads to an average energy densification of 1.14, with MY of 82.17% and EY of 93.85%. That is, even without entering the torrefaction zone, still in the over-drying zone, there was already energy densification in the materials under study. Analyzing the results presented in

Table 6, for the materials processed at 300 °C, the energy densification is even more significant, since the EDR reaches an average value of 1.84, with a MY of 30.80% and EY of 56.69%. These values are in line with the values calculated for materials most commonly used in the production of energy from biomass in Europe, such as the maritime pine (

Pinus pinaster), which has EDR, MY, and EY values of, respectively, 1.55%, 30.50%, and 47.41% [

89]. With the results related to the direct increase of heating value, but mainly with the EDR values, there is an energetic densification of the materials. This increase in energy density allows an evaluation of the possibility of exporting materials, especially if they are subjected to a densification process, for example, through the production of pellets [

90]. This can contribute to the optimization of logistical processes, which still need to be evaluated and quantified [

91]. The combination of the improvement of properties related to logistics, namely the increase in energy density, is in accordance with the properties found in commercial coals, namely bituminous and sub-bituminous coals. In fact, with the energy content above 25 MJ·kg

−1, the heat-treated sugarcane bagasse approaches the values that these coals normally present. Thus, the torrefied sugarcane bagasse presents itself as a real alternative for the replacement of coal in the thermoelectric plants, especially because, as presented in the work of Nunes et al. (2020), in addition to the energy properties, most of the torrefied biomasses have other properties that allow this substitution, namely the Hardgrove Grindability Index (HGI), which also presents similar values to those of coal [

92].

6. Conclusions and Future Developments

The sugarcane industry presents environmental problems, since it generates large amounts of waste that are normally valued energetically in sugar mills. However, growth in the industry has also led to increased production of waste, making it impossible to discharge the quantities generated. These residues have the potential to be exported for energy recovery in other areas, namely in Europe, where the demand for and consumption of biomass for energy has assumed particular importance. However, the low density of the material, associated with other problems common to biomass such as fermentation of the product, make export very difficult and costly.

The possibility of using thermochemical conversion technologies such as torrefaction to improve the energy potential of sugarcane bagasse presents itself as a highly promising alternative, as demonstrated by the results obtained in the tests performed. The improved energetic properties associated with energy densification make heat-treated sugarcane bagasse an asset to the energy market, mainly regarding the replacement of coal in the large-scale generation of energy.

Further studies are still needed, mainly to define the optimal temperature to be used in torrefaction, since high mass loss can hinder the economic viability of projects, by using, for example, a response surface methodology (RSM), which explores the relationships between several explanatory variables and one or more response variables. It is also necessary to carry out new tests with a larger number of samples, so that the results can be statistically validated, since in the present study, it was not possible to carry out a statistical study of the results, because, as previously mentioned, the tests were only conducted in triplicate. An assessment of the supply chain factors, namely those related to transport costs and cargo conditioning in long-distance transport, similar to what already happens with wood pellet supply chains, should be carried out as well. Associated with this issue, there is also a need to carry out studies on the potential for mechanical densification through the production of pellets or briquettes of the resulting torrefied material.