Abstract

Development of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) has permitted the automatization of many tasks originally achieved with manned vehicles in underwater environments. Teams of AUVs designed to work within a common mission are opening the possibilities for new and more complex applications. In underwater environments, communication, localization, and navigation of AUVs are considered challenges due to the impossibility of relying on radio communications and global positioning systems. For a long time, acoustic systems have been the main approach for solving these challenges. However, they present their own shortcomings, which are more relevant for AUV teams. As a result, researchers have explored different alternatives. To summarize and analyze these alternatives, a review of the literature is presented in this paper. Finally, a summary of collaborative AUV teams and missions is also included, with the aim of analyzing their applicability, advantages, and limitations.

1. Introduction

Over the years, a large number of AUVs are being designed to accomplish a wide range of applications in the scientist, commercial, and military areas. For oceanographic studies, AUVs have become very popular to explore, collect data, and to create 3D reconstructions or maps [1,2]. At the oil and gas industry, AUVs inspect and repair submerged infrastructures and also have great potential in search, recognition, and localization tasks like airplane black-boxes recovery missions [3,4]. AUVs are also used for port and harbor security tasks such as environmental inspection, surveillance, detection and disposal of explosives and minehunting [5,6].

Design, construction, and control of AUVs represent such a challenging work for engineers who must face constraints they do not encounter in other environments. Above water, most autonomous systems rely on radio or spread-spectrum communications along with global positioning. In underwater environments, AUVs must rely on acoustic-based sensors and communication. Design and implementation of new technologies and algorithms for navigation and localization of AUVs—especially for collaborative work—is a great research opportunity.

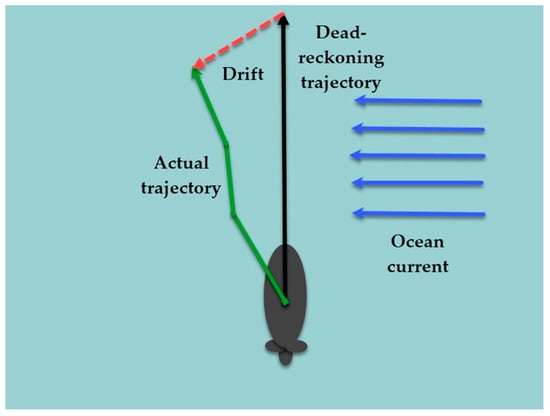

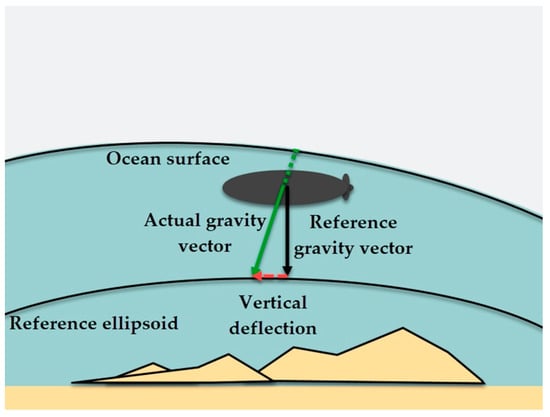

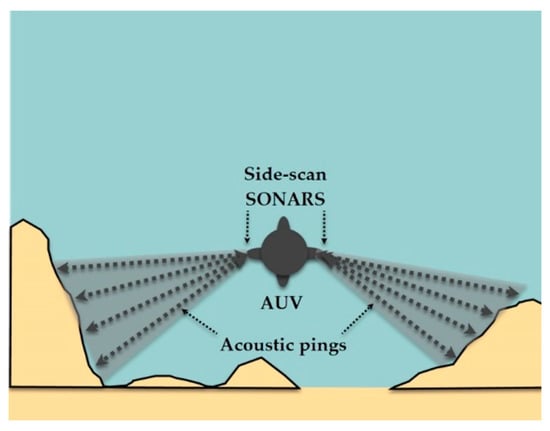

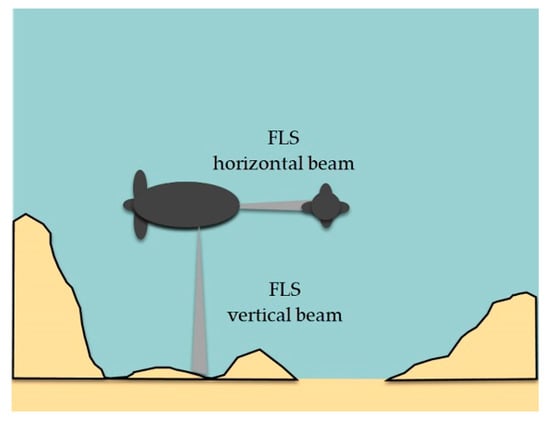

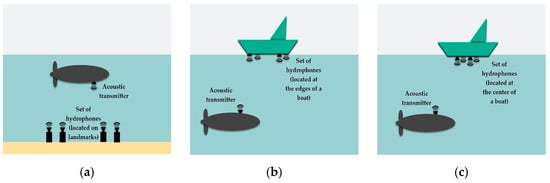

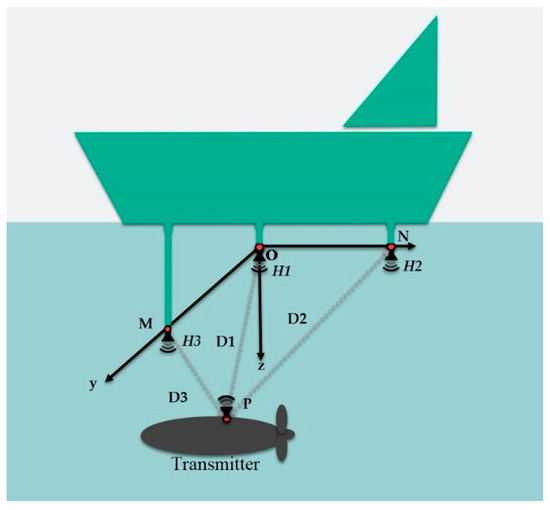

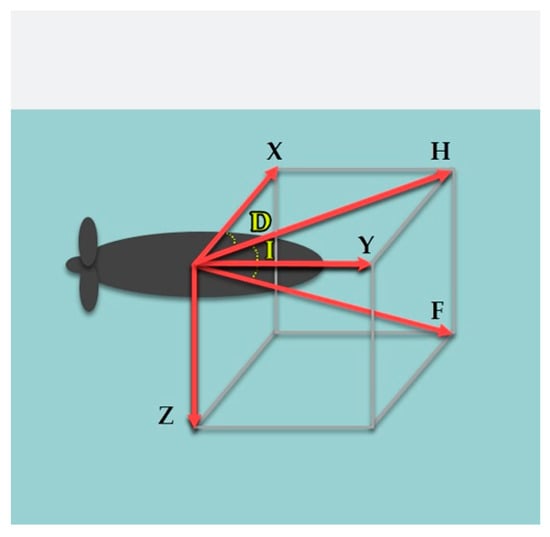

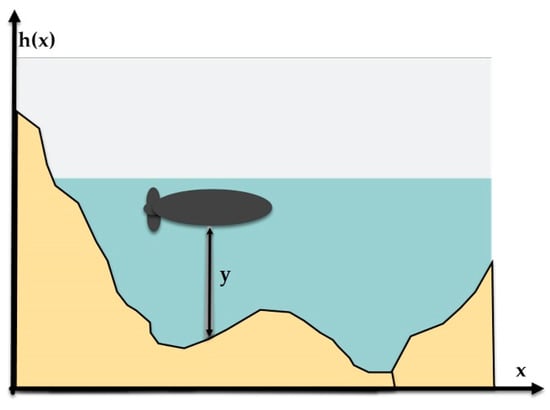

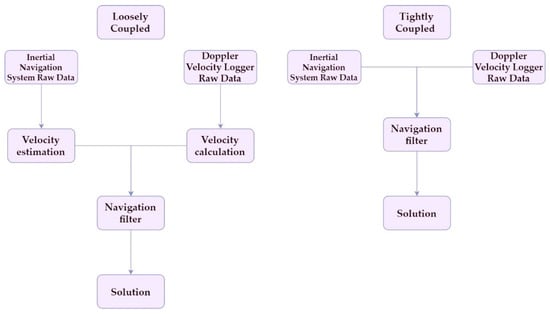

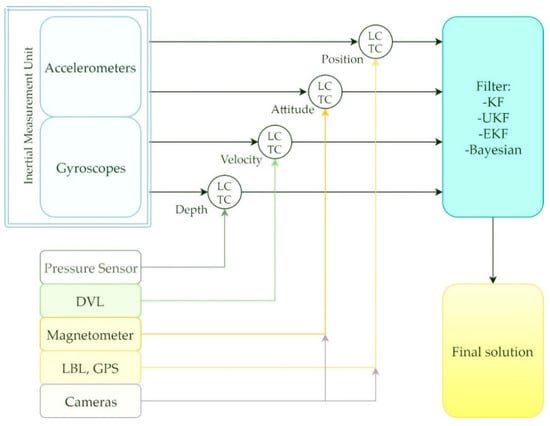

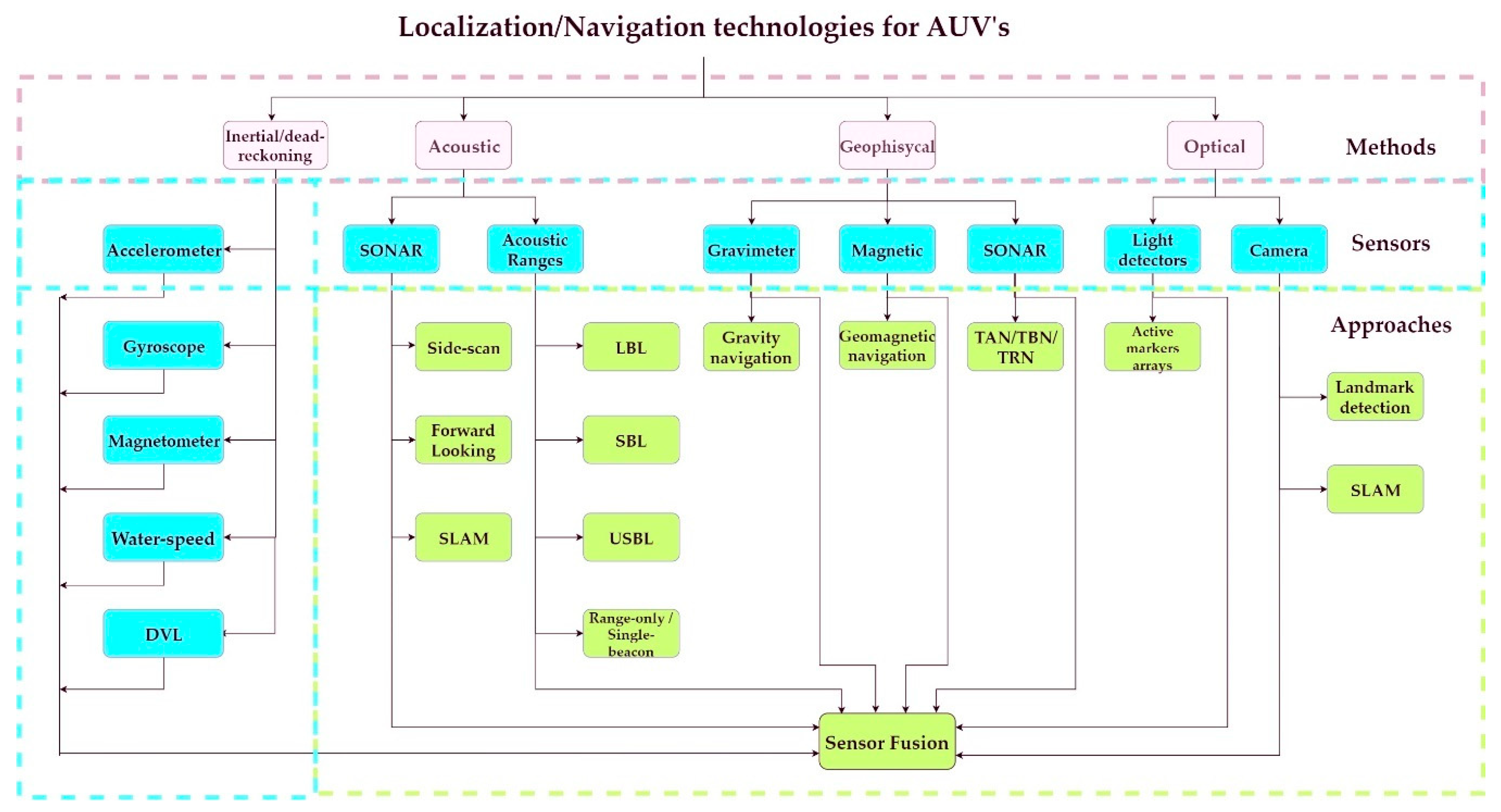

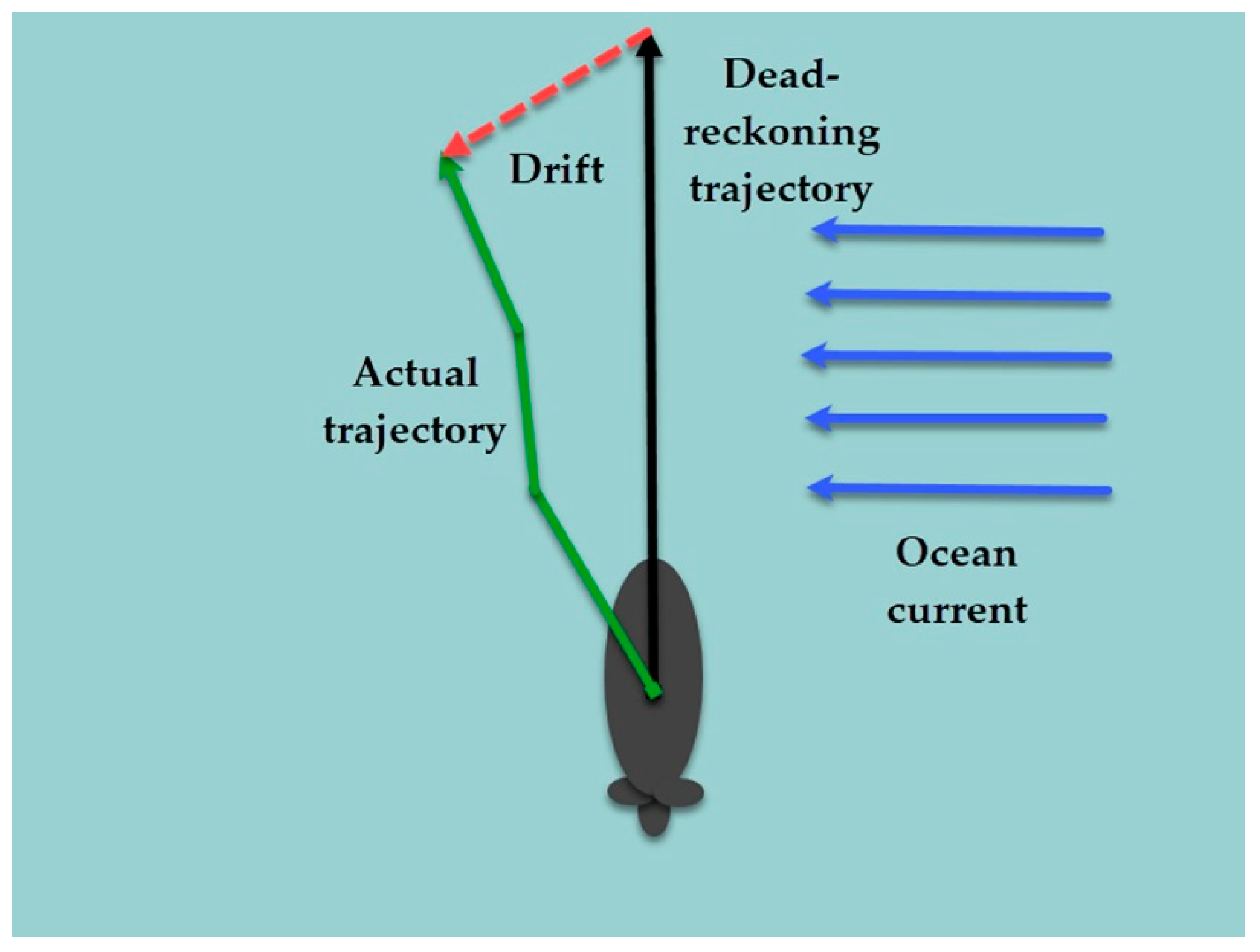

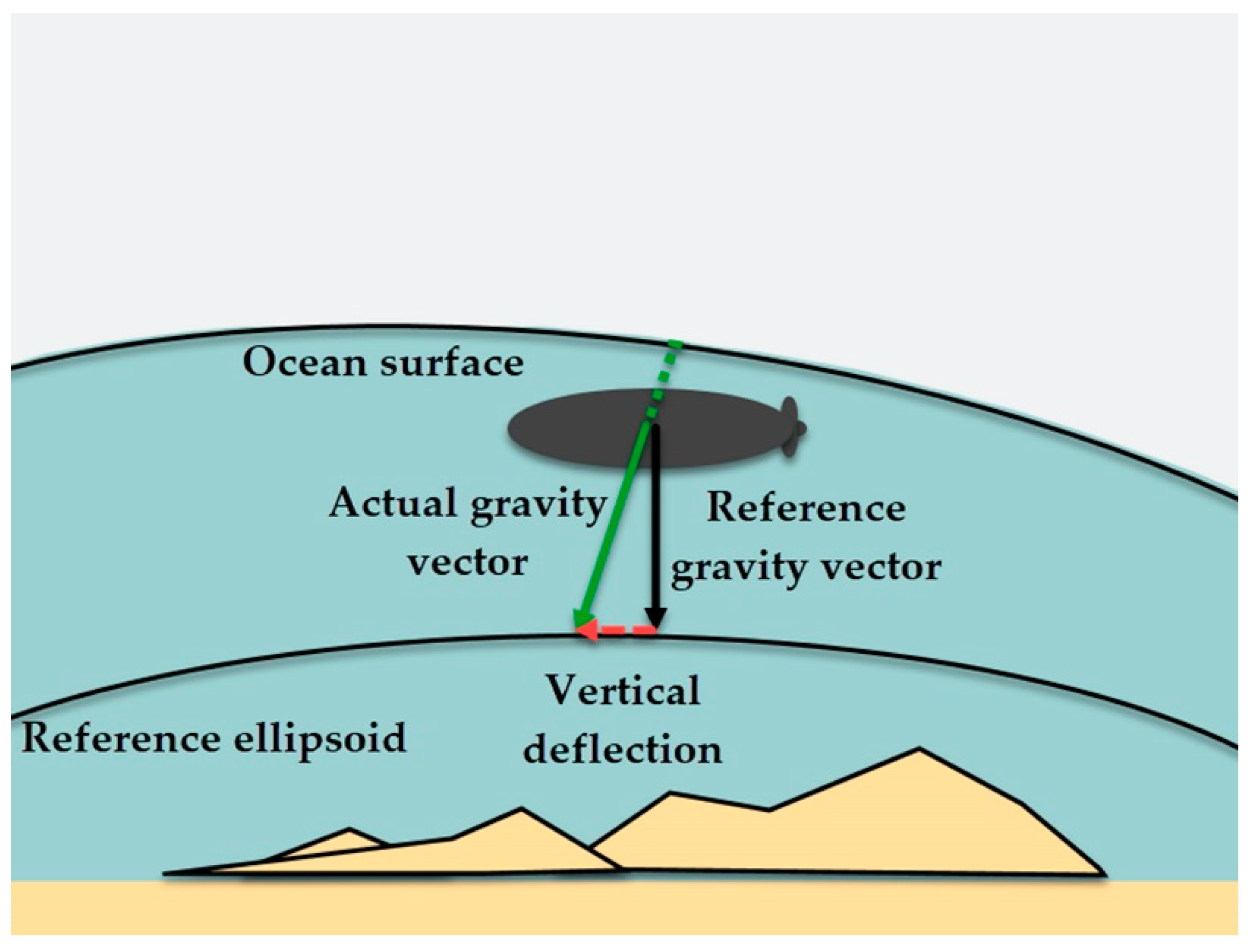

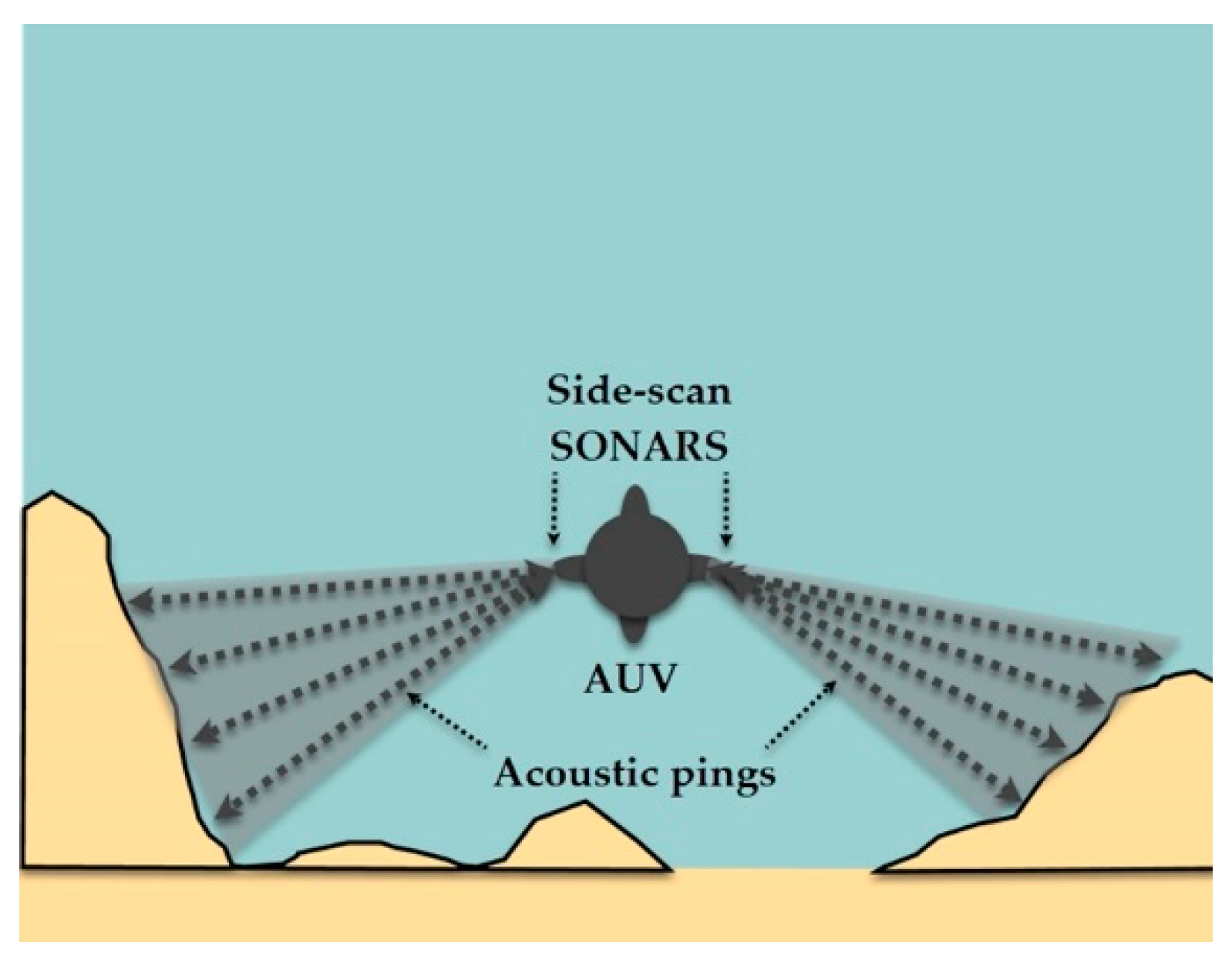

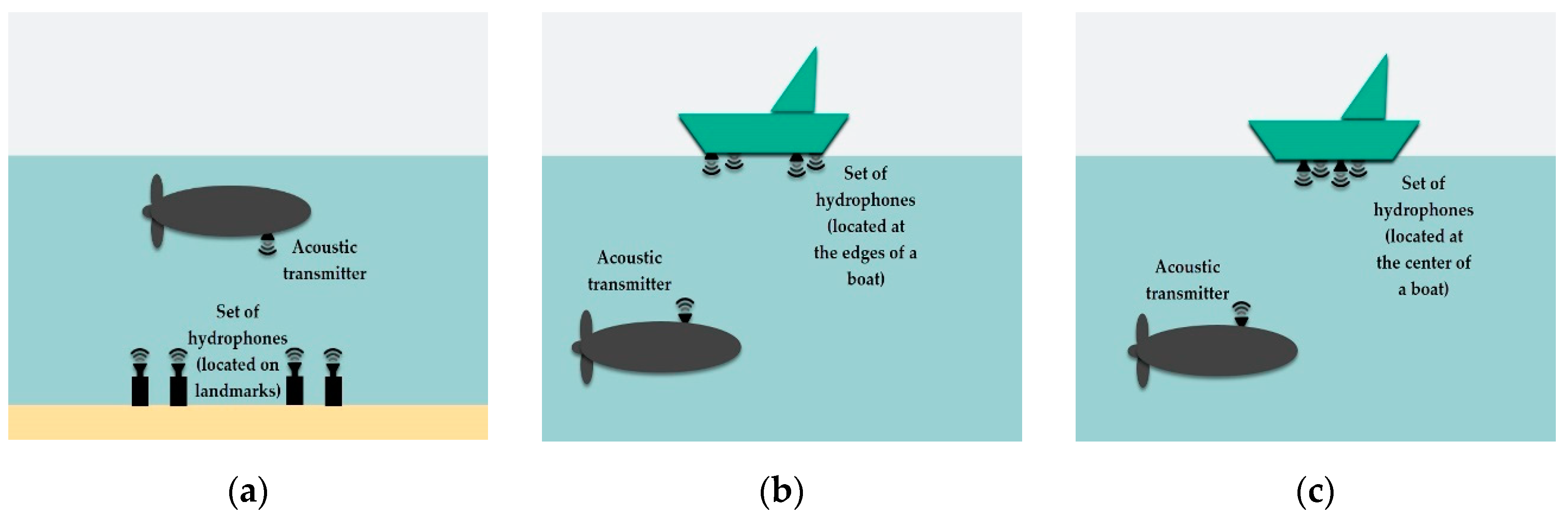

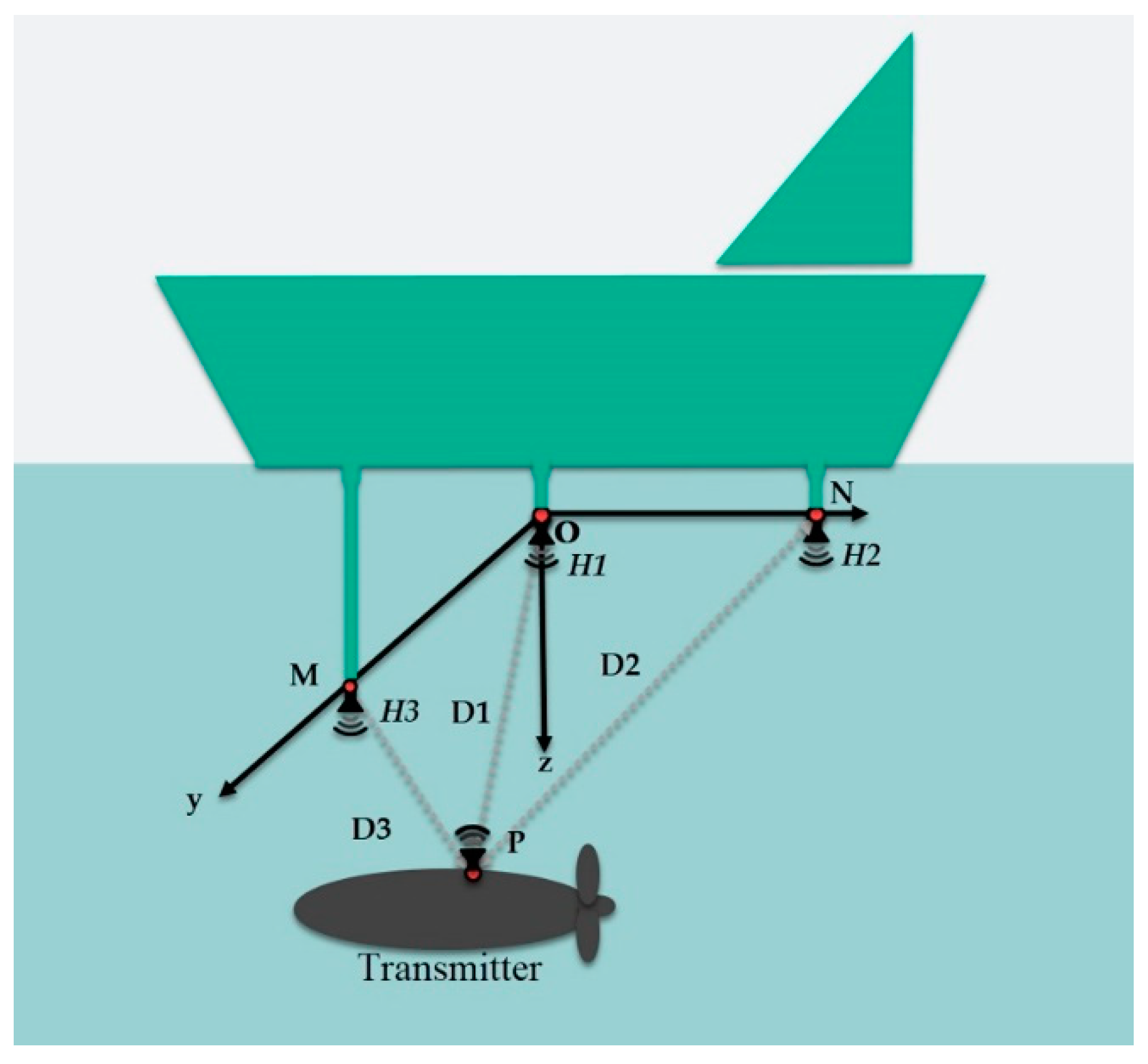

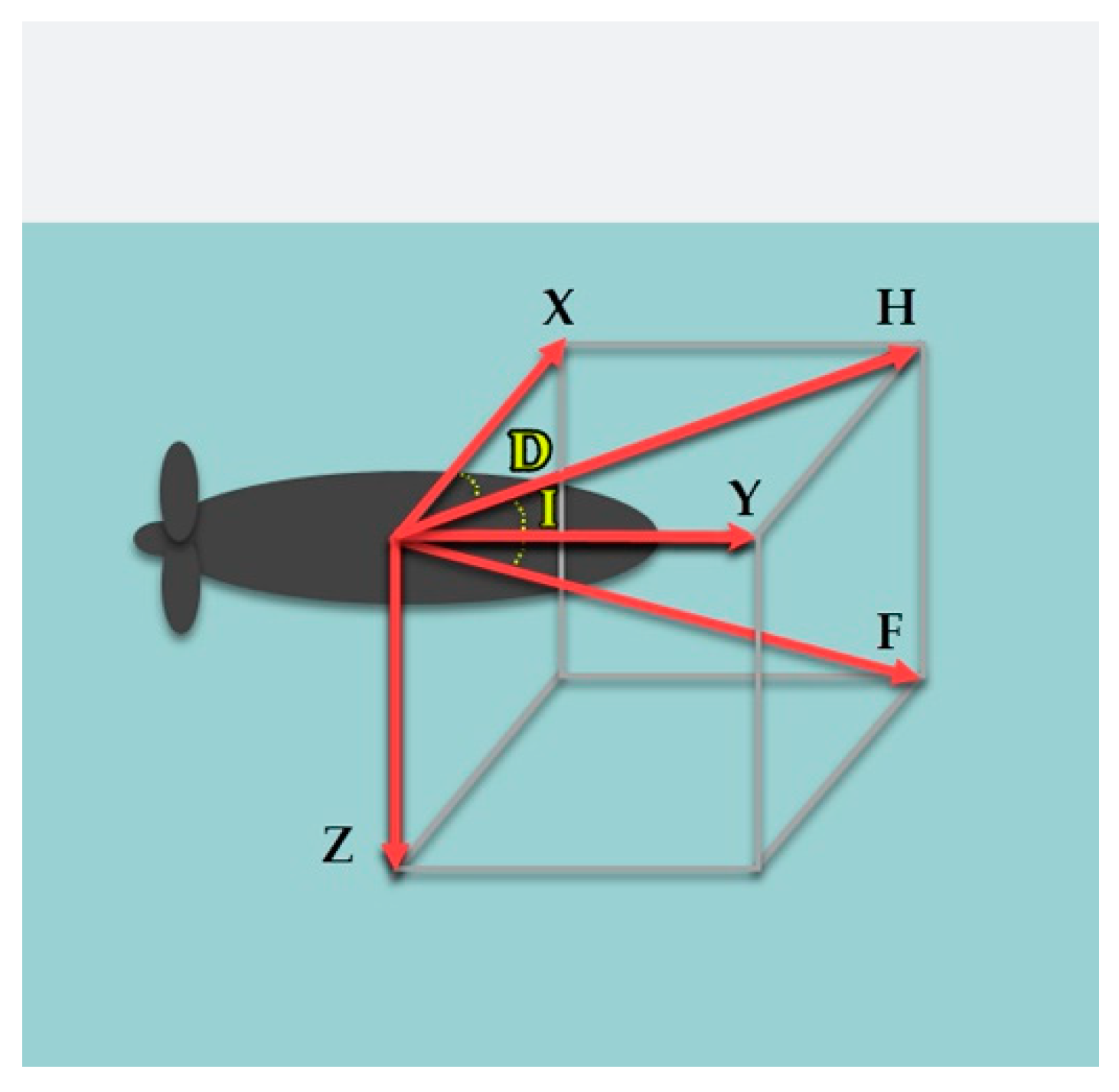

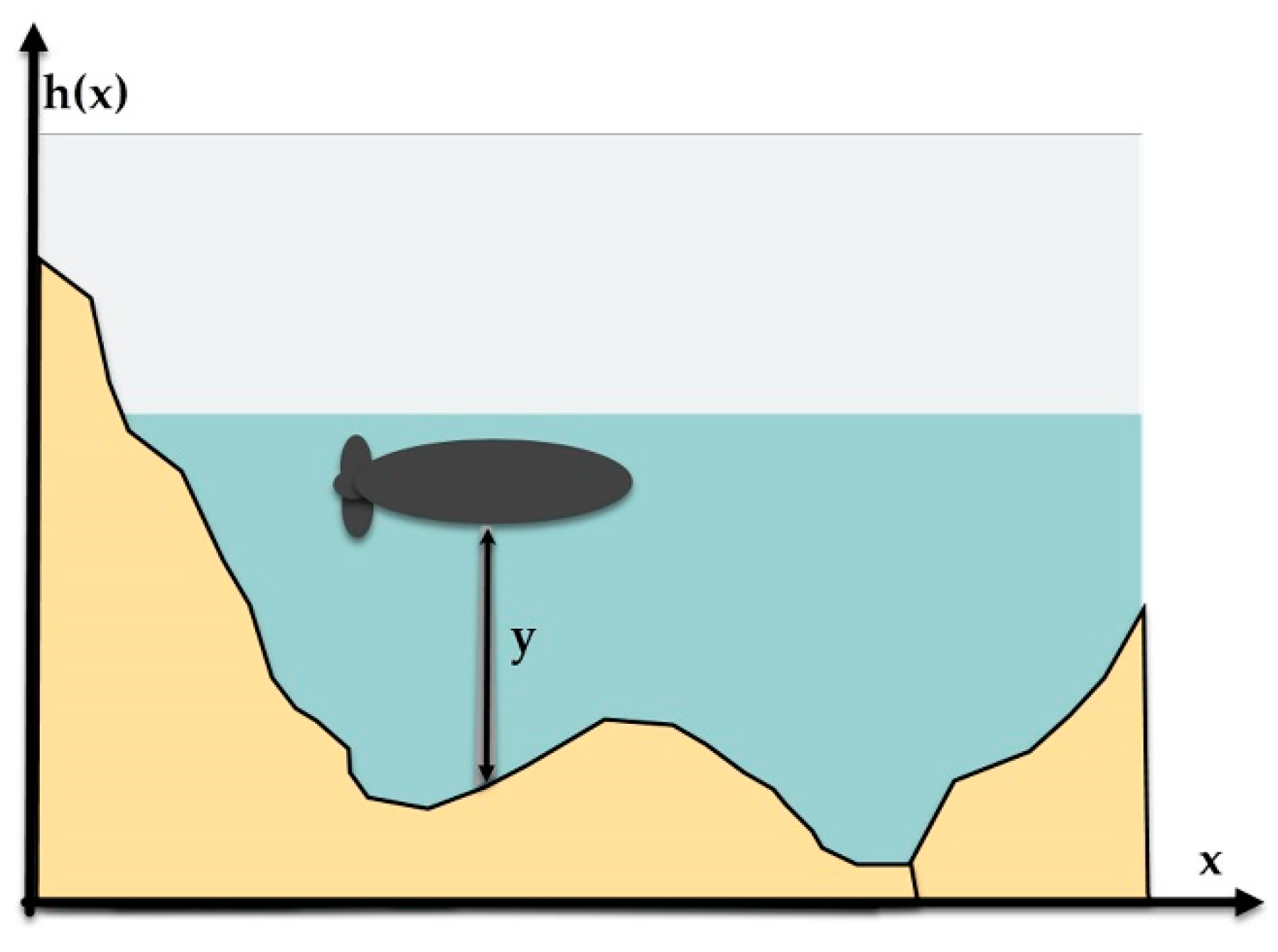

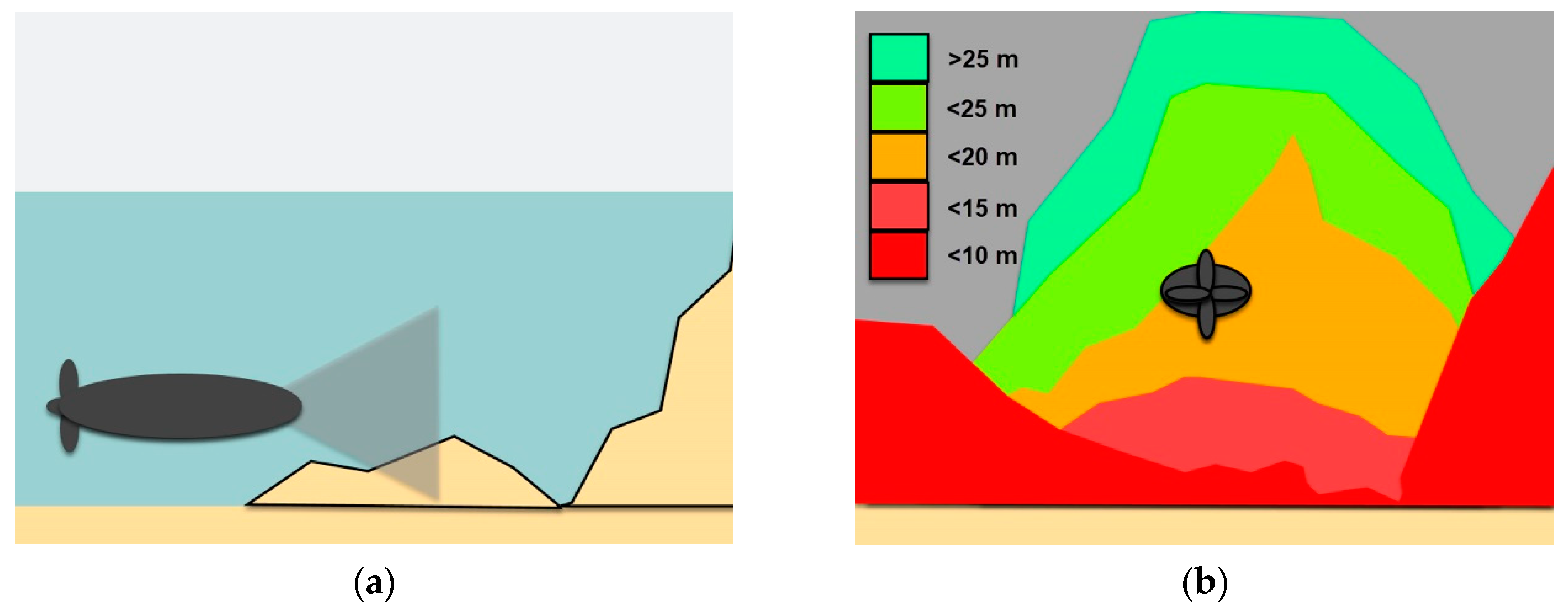

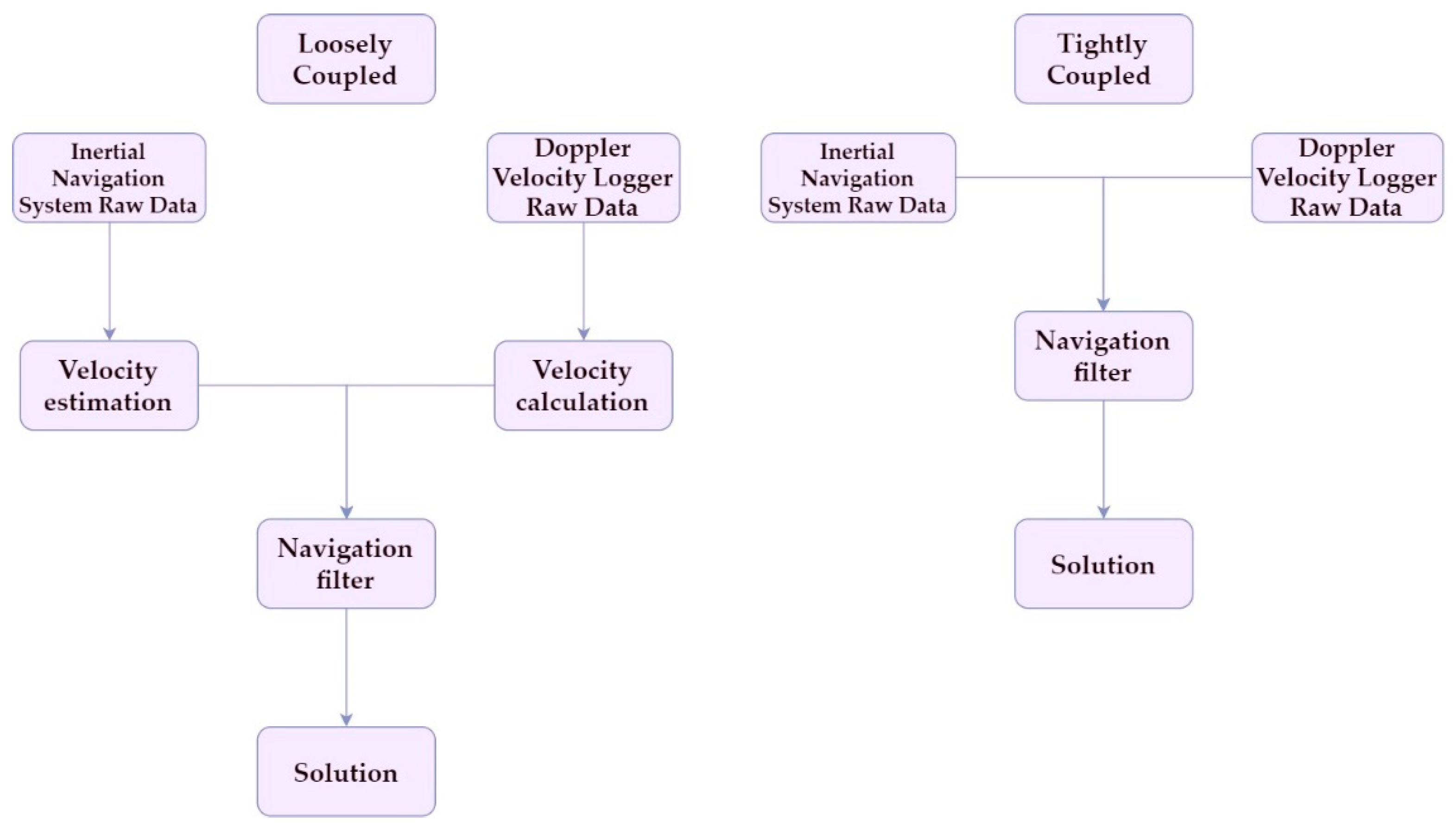

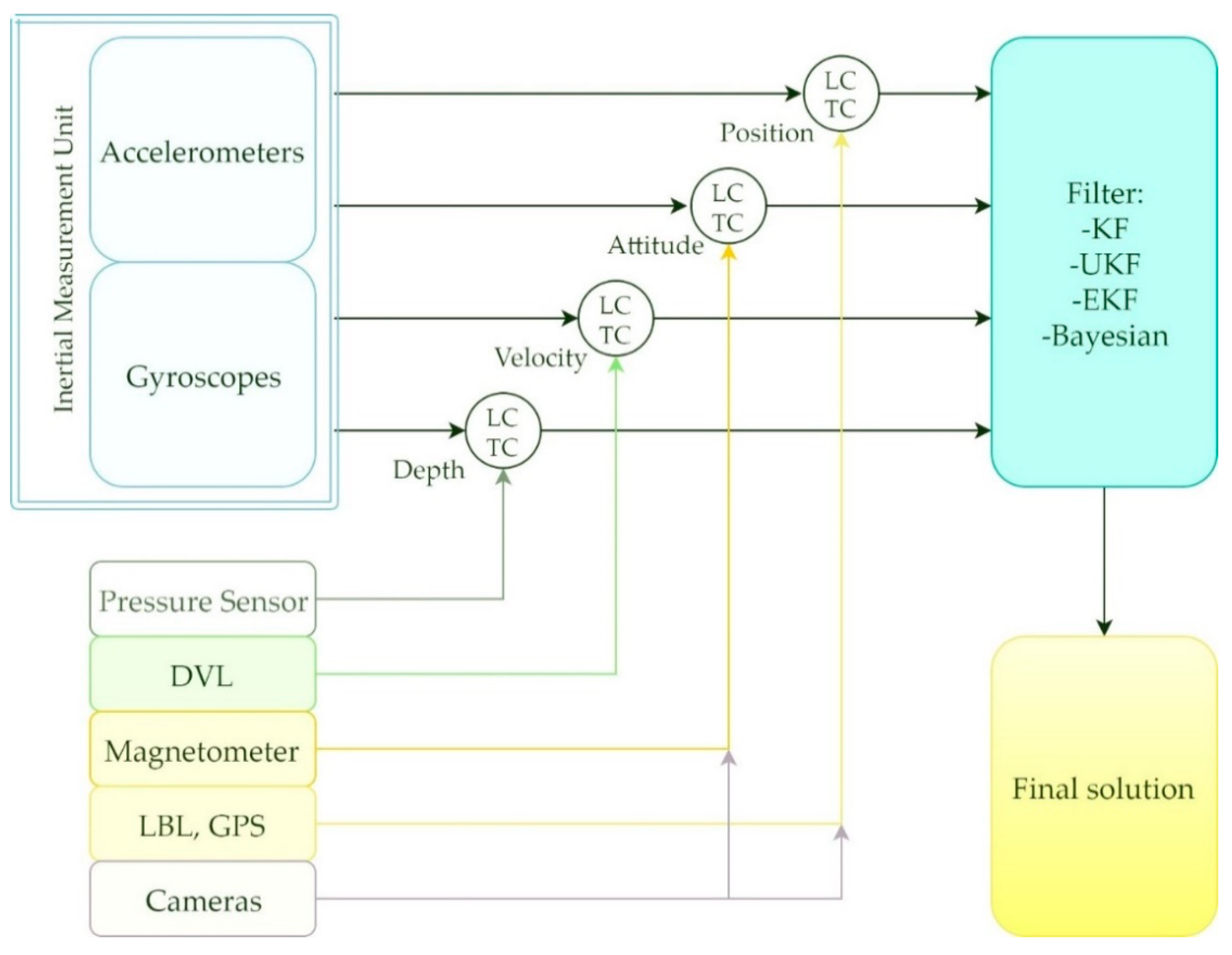

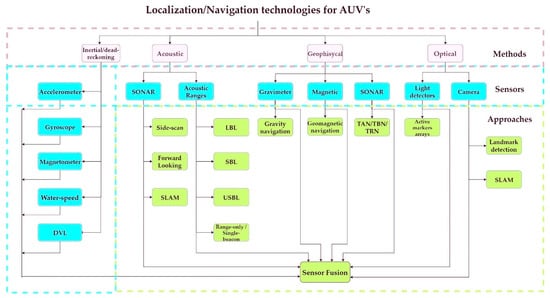

Before establishing a collaborative scheme for AUVs, the problem of localization and navigation must be addressed for every vehicle in the team. Traditional methods include Dead-Reckoning (DR) and Inertial Navigation Systems (INS) [7]. DR and INS are some of the earliest established methods to locate an AUV [8]. These systems rely on measurements of the water-speed and the vehicle’s velocities and accelerations that, upon integration, leads to the AUV position. They are suitable for long-range missions and have the advantage to be passive methods—they do not need either to send or receive signals from external systems—resulting in a solution immune to interferences. Nevertheless, the main problem of them is that the position error growths over time—which is commonly known as accuracy drift—as a result of different factors such as the ocean currents and the accuracy of the sensors itself, which are not capable of sensing the displacements produced by external forces or the effects of earth’s gravity. The use of geophysical maps to matching the sensors measurements is an alternative to deal with the accuracy drifts of the inertial systems. This method is known as Geophysical Navigation (GN) [9] and allows accomplishing longer missions maintaining a position error relatively low. However, there is a need for having the geophysical maps available before the mission, which is one the main disadvantages of GN along with the computational cost of comparing and matching the map with the sensors data. Acoustic ranging systems have been another common alternative for AUV navigation [10]. These systems can be implemented using acoustic transponders to locate an AUV in either global or relative coordinates. However, most of them require complex infrastructure and the cost of such deployments could be higher compared with other methods. In recent years, researchers are exploring new alternatives for AUV localization and navigation. Optical technologies have become very popular for robots and vehicles at land or air environments [11], but face tough conditions in underwater environments that have delayed the development of such technologies for AUVs. When the underwater conditions permit a proper light propagation and detection, visual-based systems can improve significantly the accuracy of the position estimations and reach higher data rates that acoustic systems. Finally, recent advancements in terms of sensor fusion schemes and algorithms are contributing to the development of hybrid navigation systems, which takes the advantages of different solutions to overcome their weaknesses. A sensor fusion module improves the AUV state estimation by processing and merging the available sensors data [12]. Some of the common sensors used for it are the inertial sensors of an INS, Doppler Velocity Loggers (DVL), and depth sensors. Recently, the INS measurements are also being integrated with acoustic/vision-based systems to produce a solution that, beyond reducing the accuracy drifts of the INS, will have high positioning accuracy in short-ranges. All these technologies are addressed in Section 2 of this work, which is organized as shown in Figure 1, including the main sensors used and the different approaches taken.

Figure 1.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) technologies for localization and navigation.

After solving the problem of self-localization and navigation, other challenges must be addressed to implement a collaborative team of AUVs. Since there is a need for sharing information between the vehicles, communication is an important concern. The amount and size of the messages will depend on the collaborative scheme used, the number of vehicles and the communication system capabilities. Acoustic-based performs better than light-based communication in terms of range, but not in data rates. It also suffers from many other shortcomings such as small bandwidth, high latency and unreliability [13]. Despite its notable merits in the terrestrial wireless network field, radio-based communication has had very few practical underwater applications to date [14]. The collaborative navigation scheme is also a mandatory issue to be considered. The underwater environment is complex by itself to navigate at, and now multiple vehicles have to navigate among each other. A proper formation has to ensure safe navigation for every single vehicle. These topics are analyzed in Section 3, which also includes a review on the main collaborative AUV mission: surveillance and intervention. Since there is no need to interact with the environment, survey missions are simpler to implement and have been performed successfully for different applications, such as mapping or object searching and tracking. Intervention missions are usually harder due to the complexity of the manipulators or actuators needed. In either case, since an experimental set up is difficult to be reached, many of the efforts made are being tested in simulation environments.

3. Collaborative AUVs

Once the navigation and localization problem for the AUVs is solved, a scheme for collaborative work between a group of robots can be proposed. Collaborative work refers to an interaction of two or more AUVs to perform a common task which can be collaborative navigation, exploration, target search, and object manipulation. Using a team of AUVs navigating on a certain formation has the potential to significantly expand the applications for underwater missions; such as those that require proximity to the seafloor or to cover a wide area for search, recovery, or reconstruction. At first, researchers focused their work on how multiple vehicles could obtain data simultaneously from the same area of interest. Nowadays, their focus has moved to the trajectory design and operation strategies for those multi-vehicle systems [99].

3.1. Communication

The rapid attenuation of higher frequency signals and the unstructured nature of the undersea environment make difficult to establish a radio communication system for AUVs. For those reasons, wireless transmission of signals underwater—especially for distances longer than 100 m—relies almost only on acoustic waves [14,100]. Underwater acoustic communication using acoustic modems consists of transforming a digital message into sound that can be transmitted under water. The performance of these systems changes dramatically depending on the application and the range of operation [101]. The main factors to choose an underwater acoustic modem are:

- Application: Consider the type and length of message (Command and control messages, voice messages, image streaming, etc.) frequency of operation and operating depth.

- Cost: Depending on the complexity and performance, from some hundreds up to $50,000 (USD).

- Size: Usually cylindrical, with lengths from 10 cm to 50 cm.

- Bandwidth: Acoustic modems can perform underwater communication at up to some kb/s. Length of the message and time limitations must be considered

- Range: Range of operation for the vehicle’s communication has impact on the cost of the system. Acoustic modems are suitable from short distances up to tens of km. Considerer than a longer range will increase the latency and power consumption of the system.

- Power consumption: Depending on the range and modulation, the power consumption is in the range of 0.1 W to 1 W in receiving mode and 10 W to 100 W in transmission mode.

Table 5 contains a few options of acoustic modems commercially available.

Table 5.

Commercial acoustic modems.

The working principles of underwater acoustic communication can be described as follows [110]: First, information is converted into an electrical signal by an electrical transmitter. Second, after digital processing by an encoder, the transducer converts the electrical signal into an acoustic signal. Third, the acoustic signal propagates through the medium of water and propagates the information to the receiving transducer. In this case, the acoustic signal is converted into an electrical signal. Finally, after the digital signal is deciphered by the decoder, the information is converted to an audio, text or picture by the electrical receiver.

Acoustic communications face many challenges, such as, small bandwidth, low data rate, high latency, and ambient noise [111]. These shortcomings might provoke that a cycle of communication in a collaborative mission take several seconds, or even more than a minute. Considering these, Yang et al. [112] analyzed formation control protocols for multiple underwater vehicles in the presence of communication flaws and uncertainties. The error Port-Hamiltonian model about the desired trajectory was introduced and then, with the existence of relative information constraints or uncertainties, the formation control law was achieved by solving specific limitations of the linear matrix inequality problem. Abad et al. [113] introduced a communication scheme between the AUVs and a unique representation of the overall vehicle state that limits message size. To limit data sent, every reported position and path plan is encoded using a grid encoding scheme. Authors implemented a decentralized model predictive control algorithm—centralized schemes are typical for swarms of AUVs—to control teams of AUVs that optimizes vehicle control inputs to account for the limitations of operating in an underwater environment. They simulate their proposal and showed the effectiveness of their approach in a Mine/Countermine mission. Other way to deal with acoustic communication issues was presented by Hallin et al. [114]. They proposed that enabling the AUVs to anticipate acoustic messages would improve their ability to successfully complete missions. They outlined an approach to AUV message anticipation in AUVish-BBM (BBM suffix includes the initials of the researchers directly involved in dialect development: Beidler, Bean and Merrill [115]), an acoustic communications language for AUVs [116], based on a University of Idaho-developed paradigm called Language-Centered Intelligence (LCI). They demonstrated a new application of LCI in the field of cooperative AUV operations and argued that message anticipation can be effectively deployed to correct message errors. The structure, content, and context of individual messages of AUVish-BBM, together with its associated communication protocol, supply a systematic framework that can be utilized to anticipate messages expressed by AUVs performing collaborative missions.

The absence of an underwater communication standard has been a problem for collaborative teams of AUVs. In 2014, Potter et al. presented the JANUS underwater communication standard [117], a basic and robust tool for collaborative underwater communications designed and tested by the NATO Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation. This opened the possibilities for simple integration of different robots using this standard [118,119,120,121] for collaborative tasks as underwater surveillance.

To improve the performance of underwater communication, optical technologies have been tested either stand-alone [122,123] or as a complement for an acoustic system [100]. Laser submarine communication has some advantages such as a high bit rate, higher security and broad bandwidth. Blue-green light (whose wavelength is 470–580 nm) penetrates water better and its energy attenuation is less than any other wavelength light [124]. Thus, researchers have explored optical underwater communication systems based in blue-green light, to allow an underwater vehicle to receive a message from an aerial/spatial system at any depth despite its actual speed, course and distance from the transmitter. Wiener et al. [122] were seeking for a system to deliver a message from a satellite to a submarine, avoiding the need for the submarine to navigate close to the surface for retrieving the message as happened with the radio-frequency systems used at the time. Authors stated that blue light has the potential to accomplish the result expected in the future. However, their research was only a brief representation of what could be expected when working in such a difficult environment. Puschell et al. [123] performed the first demonstration of a two-way laser communication between a submarine vehicle and an aircraft; and concluded that a blue-green laser communication system could, someday, reach operational requirements. Sangeetha et al. [125] made experiments to study the optical communication between an underwater body and a space platform using a red laser with a 635 nm wavelength. Results showed that the performance of the red-light system was lower than the expected for a blue-light system in terms of the attenuation coefficient observed. Corsini et al. [126] worked on an optical wireless communication system where both, transmitter and receiver, where at underwater. The optical signal with a 470 nm wavelength was obtained modulating two LED arrays and received by an avalanche photodiode module. Error free transmission was achieved in the three configurations under test (6.25 Mbit/s, 12.5 Mbit/s, and 58 Mbit/s) through 2.5 m clean water.

Despite some authors as Wiener and Puschell have claimed that laser communication systems for underwater vehicles could be a possibility, recent studies showed that technology still limited. Laser-based systems cannot reach a target with a more than a few tens of meters depth under ideal conditions [127]. Thus, Farr et al. [100] developed an optical communication system that complements and integrates an acoustic system. The result was an underwater communication system capable to offer high data rates and low latency when within optical range; combined with long range and robustness of acoustics when outside of optical range. Authors have demonstrated robust multi-point, low power omnidirectional optical communications over ranges of 100 m at data rates up to 10 Mb/s using blue-green emitters.

3.2. Collaborative Navigation

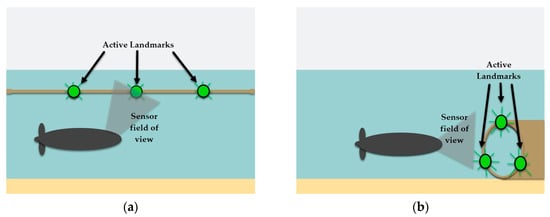

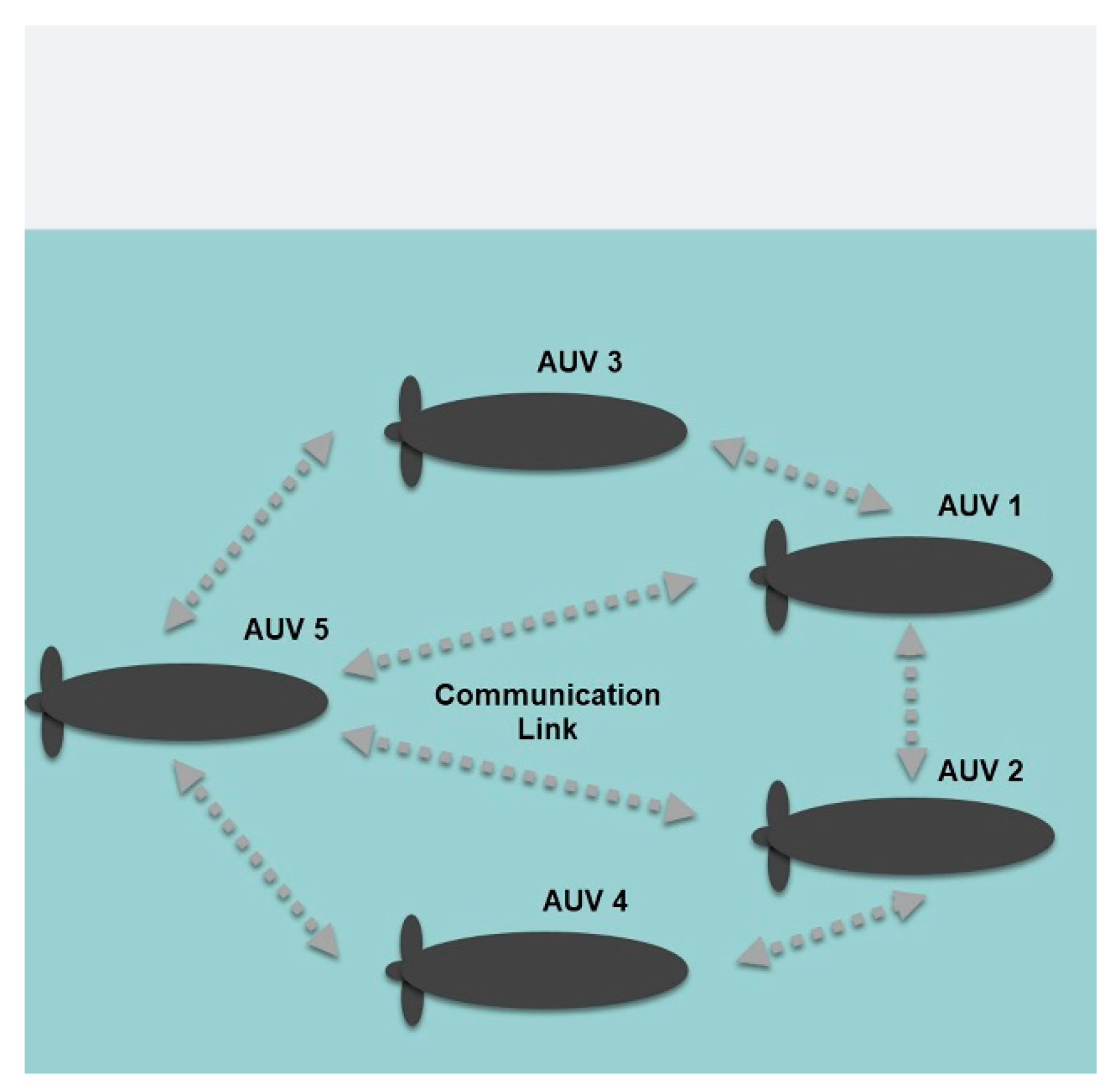

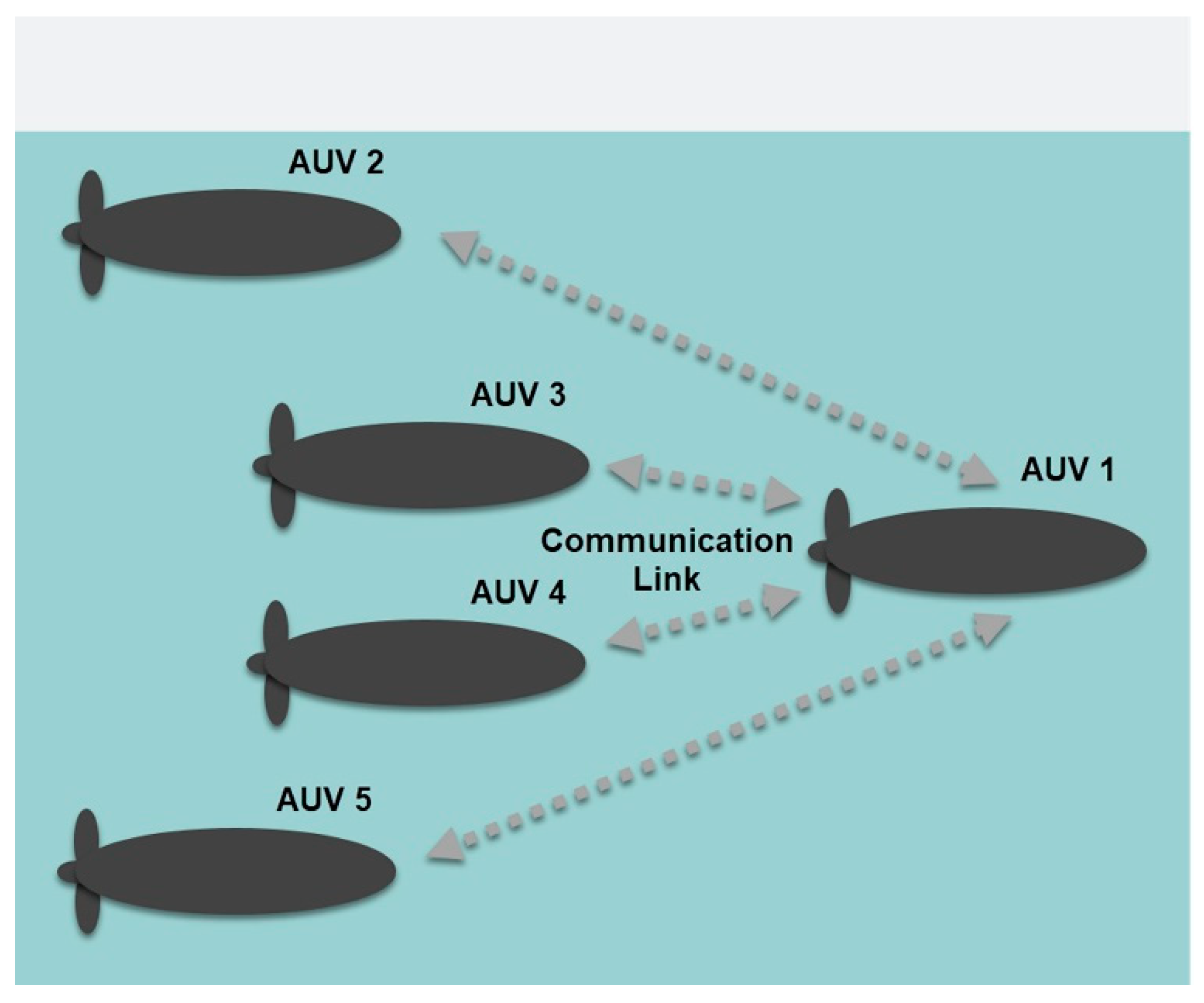

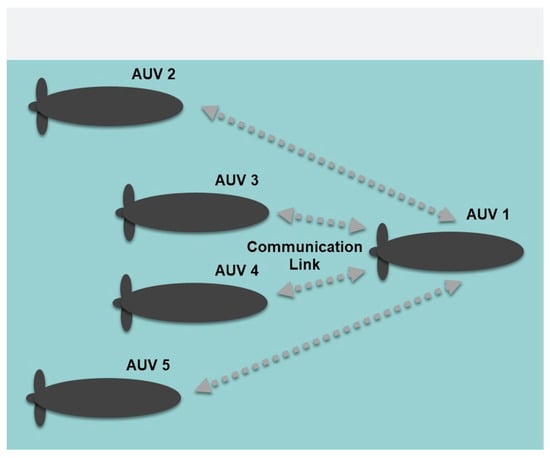

Groups of AUVs can work together under different navigation schemes, which are generally parallel or leader-follower [110]. On a parallel formation (shown in Figure 15), all AUVs are equipped with the same systems and sensors, to locate and navigate themselves precisely and to communicate with its neighbor AUVs.

Figure 15.

Parallel navigation of AUVs.

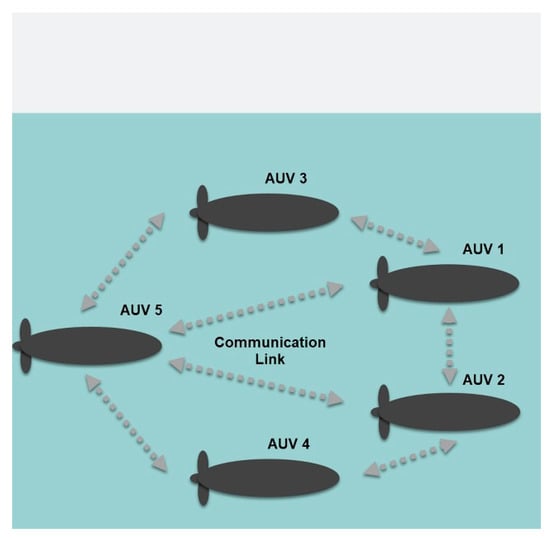

In a leader-follower scheme (shown in Figure 16), leader AUV is equipped with high-precision instruments meanwhile follower AUVs are equipped with low-precision equipment [128]. Communication is only required between the vehicle leader and its followers, there is no need for the followers to communicate with each other.

Figure 16.

Leader-follower navigation of AUVs with AUV 1 as a leader of the formation.

The lower cost and the reduced communications needs make the leader-follower scheme the main navigation control method of AUVs. Its basic principles and algorithms are relatively mature [110]. However, unstable communications and communication delays are still challenging problems and need to be addressed. Since there are problems with signals when multiple systems emit at the same time, co-localization of AUVs is mostly based on time synchronization. However, time synchronization methods have some shortcomings such as the need for AUVs to go to surface to receive the synchronization signal. As an alternative, Zhang et al. [129] studied multi-AUVs collaborative navigation and positioning without time synchronization. Authors established a collaborative navigation positioning model for multi-AUVs and designed an EKF for collaborative navigation. This design only needs the time delay of the AUV itself and does not need to consider whether the AUV has synchronized with others. In simulated experiments, they compared the precision of their algorithm with a prediction model and results showed that, even when error increases over time, the precision of co-localization without time synchronization was higher. Yan et al. [130] addressed the problems of leader-follower AUV formation control with model uncertainties, current disturbances, and unstable communication. The effectiveness of the method is simulated by tracking a spiral helix curve path with one leader AUV and four follower AUVs. Considering model uncertainties and current disturbances, a second-order integral AUV model with a nonlinear function and current disturbances was established. The simulation results showed that leader-follower AUV formation controllers are feasible and effective. After an adjustment period, all follower AUVs can converge to the desired formation structure, and the formation can keep tracking the desired path.

Cui et al. [131] focused on the problem of tracking control for multi-AUV systems and proposed an adaptive fuzzy-finite time control method. In this algorithm, algebraic graph theory is combined with a leader-follower architecture for describing the communication of the system. Then, the error compensation mechanism is introduced. Finally, the application of finite time and fuzzy logic system improves the convergence rate and the robustness of multi-AUV system. The effectiveness of the proposed algorithm was illustrated by simulation. Choosing the architecture of 4 AUVs including 1 leader and 3 followers. In order to avoid the unknown internal and external interferences, the algebraic graph theory and a fuzzy logic system technique are integrated into the distributed controllers. The simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm and robustness of the multi-AUV system with a faster convergence speed compared with others algorithms.

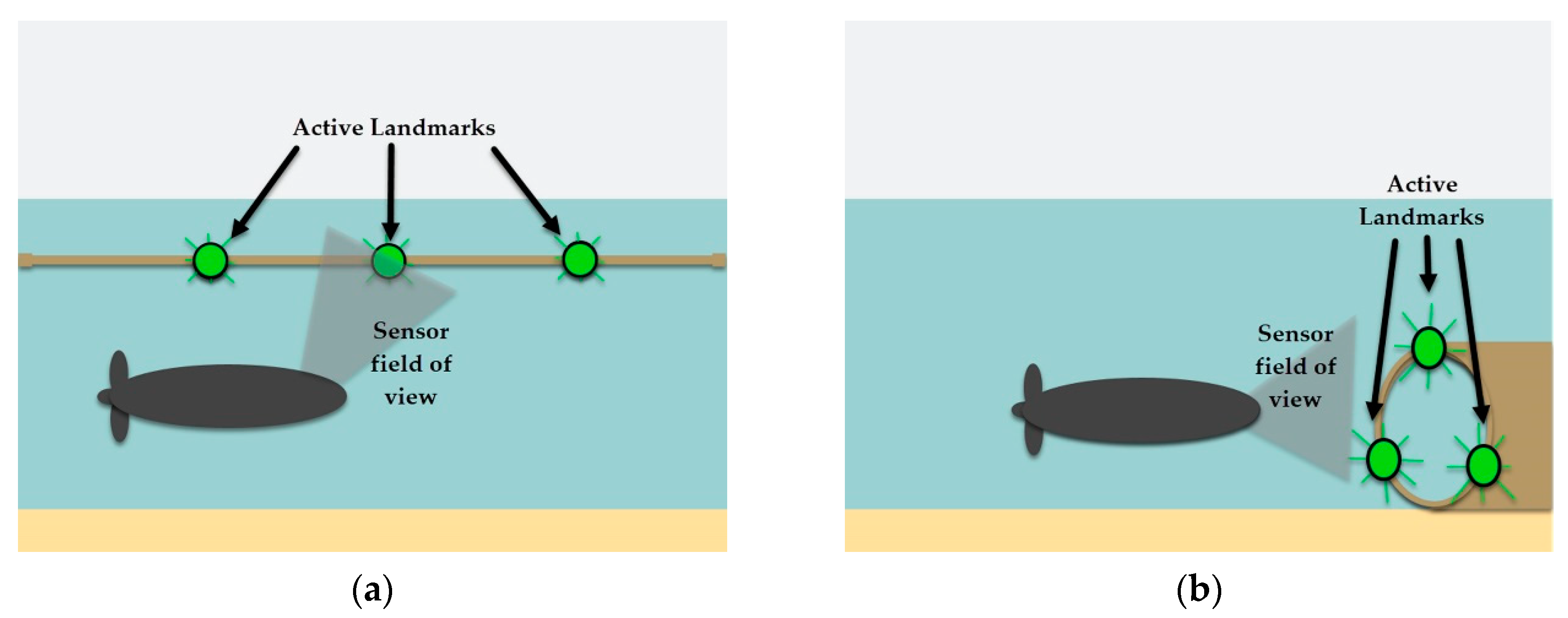

When AUVs navigate in closed formations, the delay between the transmission and reception of the acoustic signals represents a high risk. Therefore, a solution with a response time significantly faster must be explored. Bosh J. et al. [11] developed an algorithm for AUVs navigating on a close formation, where light markers and artificial vision are used to allow the estimation of the pose of a target vehicle at short ranges with high accuracy and execution speed. In the experiments presented, the filtered pose estimates were updated at approximately 16 Hz, with a standard deviation lower than 0.2 m in the distance uncertainty between vehicles, at distances between 6 m and 12 m. As expected, the results showed that the system performs adequately for vehicle separations smaller than 10 m, while the tracking becomes intermittent for longer distances due to the challenging visibility conditions underwater.

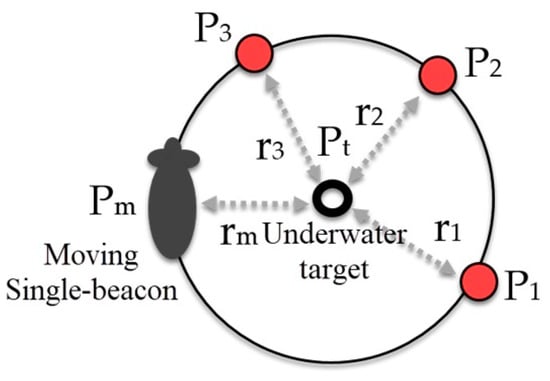

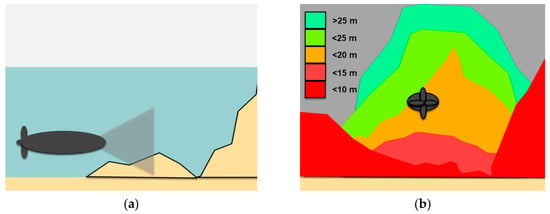

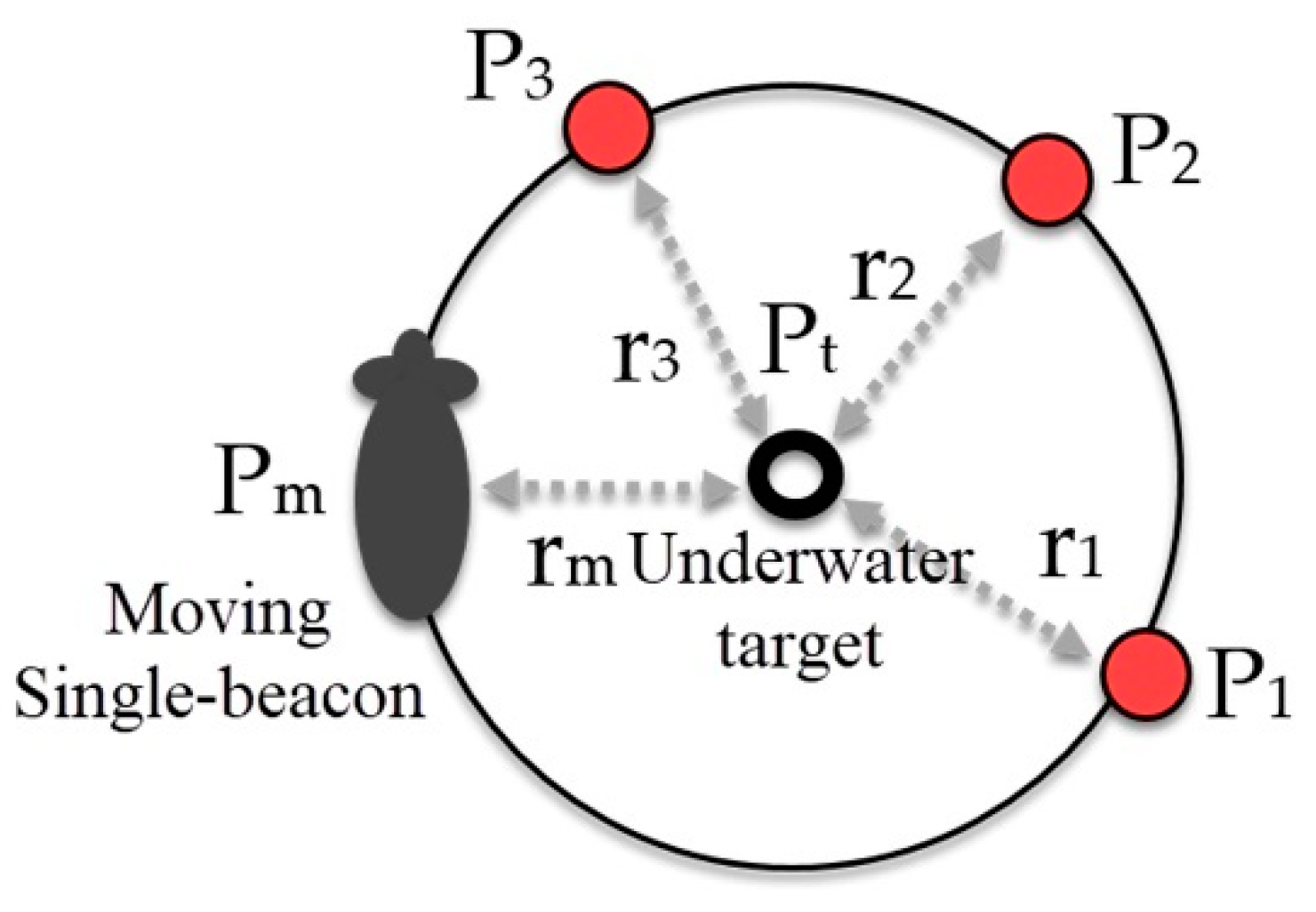

Other alternatives for cooperative navigation of AUVs is the use of systems that allow the vehicles within a team to help each other with their localization. Teck et al. [132] proposed a TBN system for cooperative AUVs. The approach consists on an altimeter and acoustic modem equipped on each vehicle and a bathymetric terrain map. The localization is performed via decentralized particle filtering. The vehicles in the team are assumed to have their system time synchronized. A simple scheduling is adopted so that each vehicle in the team broadcasts its local state information sequentially using acoustic communication. This information includes the vehicle current position, the filter estimated covariance matrix, and the latest water depth measurement. When the acoustic signal is received by another vehicle the time-of-arrival can be calculated to determine the inter-vehicle distance. Results showed that localization performance improves as the number of the vehicles in the team increase, at least up to four, and when they are in range for a proper acoustic communication. The average positioning error was in the range of a few meters in those conditions. Tan et al. [133] developed a cooperative path planning for range-only localization. Authors explored the use of a single-beacon vehicle for range-only localization to support other AUVs. Specifically, they focused on cooperative path-planning algorithms for the beacon vehicle using dynamic programming formulations. These formulations take into account and minimize the positioning errors being accumulated by the supported AUV. Implementation of the cooperative path-planning algorithms was in a simulated environment. The simulations were conducted with different types of ranging aids, each transmitted from a single beacon. The ranging aids used were: single fixed beacon, circularly moving beacon, and cooperative beacon. Experimental results were also obtained by a field trial was conducted near Serangoon Island, Singapore. Average error was reduced up to 19.1 m over a traveled distance of 1.5 km. De Palma et al. [134] made a similar approach. The problem addressed by the authors consisted of designing a relative localization solution for a networked group of vehicles measuring mutual ranges. The aim of the project was to exploit inter-vehicle communications to enhance the range-based relative position estimation. Vehicles are considered capable to know their own position, orientation, and velocity regarding a common frame. Such vehicles share their own information through their communication channel and they can obtain measurements of their relative Euclidean distance with respect to several other agents. The connection topology of the agents was represented through a relative position measurement graph and a simulation, relative to a group of 4 agents, was performed with different connection topologies. During the simulation, z error remained in the range of ± 1 m after a time-lapse of 3000 s.

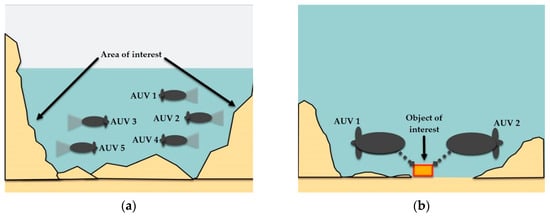

3.3. Collaborative Missions

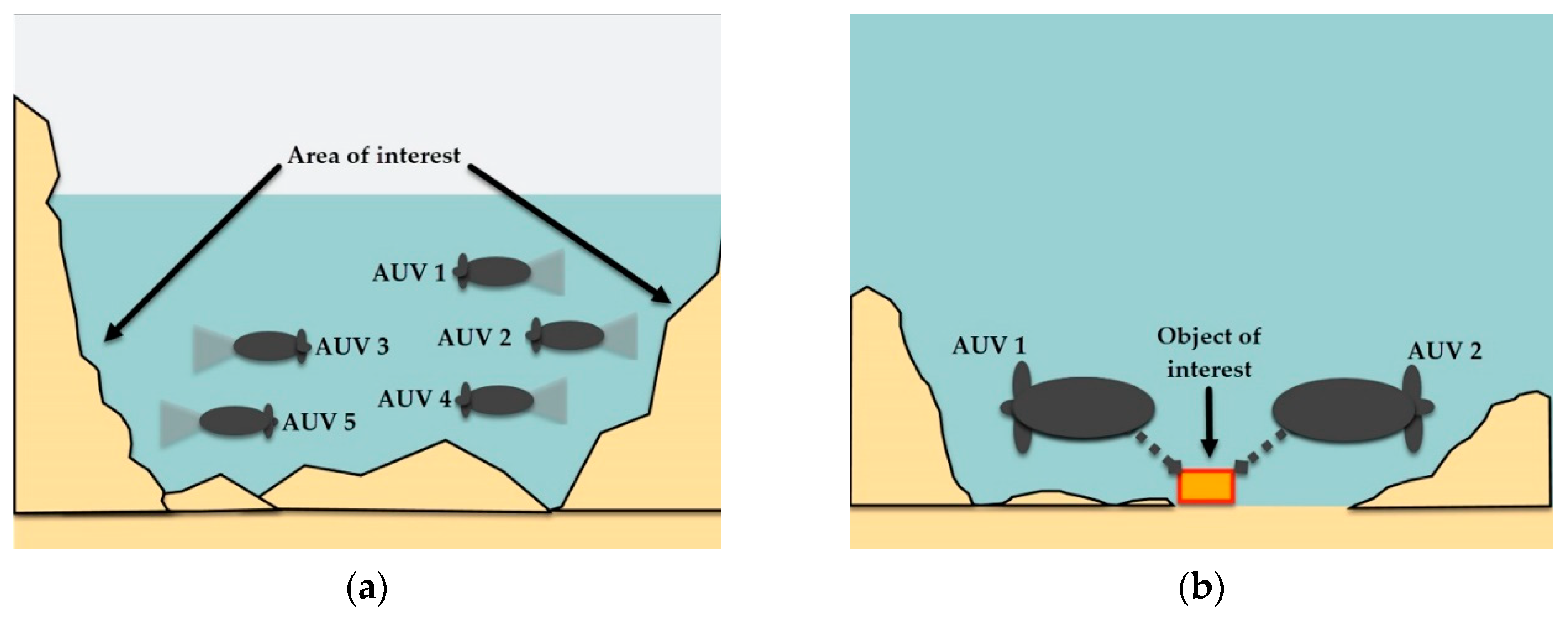

Surveillance and intervention are typically the kinds of missions designed for teams of AUVs. Surveillance missions require the AUVs to detect, localize, follow, and classify targets, inspect or explore the ocean. Meanwhile, intervention missions require the AUVs to interact with objects within the environment. Examples of both missions are represented in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Collaborative missions for AUVs. (a) Cooperative inspection of subsea formations. (b) Cooperative object recovery.

3.3.1. Search Missions

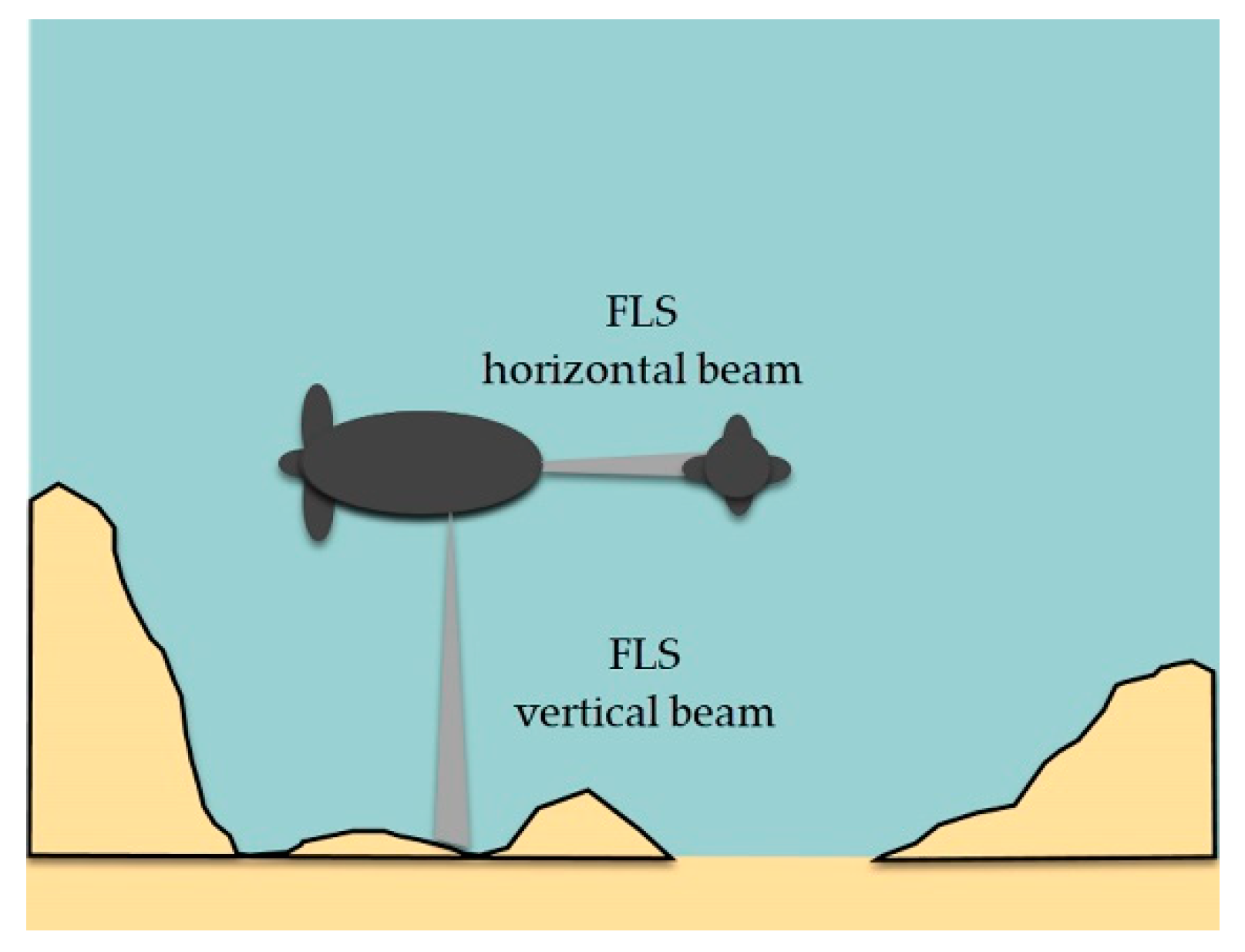

A good search mission needs to minimize the number of vehicles required and maximize the efficiency of the search. Oceanic, biologic, and geologic variability of underwater environments impact in the search performance of teams of AUVs. To address search planning in these conditions, where the detection process is prone to false alarms, Baylog J. et al. [135] applied a game theoretic approach to the optimization of a search channel characterization of the environment. The search space is partitioned into discrete cells in which objects of interest may be found. The game theory approach seeks to find the equilibrium solution of the game rather than the optimal solution to a fixed objective of maximizing the value-over-cost. To demonstrate effectiveness in achieving the game objective, a sequence of searches by four search agents over a search region was planned and simulated. Li et al. [136] proposed a sub-region collaborative search strategy and a target searching algorithm based on a perceptual adaptive dynamic prediction. The reality of the local environment is obtained by using the FLS of the multi-AUV system. The simulation experiments verified that the algorithm proposed successfully searched and tracked the target. Moreover, in the case of an AUV failure, it can also ensure that other AUVs cooperate to complete the remaining target search tasks. Algorithms for collaborative search based on Neural Networks (NN) are being designed to overcome the variability of the environment and the presence of obstacles. Iv et al. [137] presented a region search algorithm based on a Glasius Bio-inspired Neural Network (GBNN), which can be used for AUVs to perform target search tasks in underwater regions with obstacles. In this algorithm, the search area is divided into several discrete sub-areas and connections are made between adjacent neurons. AUVs and obstacles are introduced to the network as sources of excitation in order to avoid collisions during the search process. By constructing hypothetical targets and introducing them into the NN as stimulating sources of excitation, the AUVs are guided to quickly search for areas where the target is likely to exist and they can efficiently complete the search task. Sun et al. [138] designed a new strategy for collaborative search with a GBNN algorithm. In the algorithm, a grid map is set up to represent the working environment and NN are constructed where each AUV corresponds to a NN. All the AUVs must share information about the environment and, to avoid collision between the vehicles, each AUV is treated as a moving obstacle in the region. Simulation was conducted in MATLAB to confirm that through the proposed algorithm, multi-AUVs can plan reasonable and collision-free coverage path and reach full coverage on the same task area with division of labor and cooperation. Yan et al. [139] addressed a control problem for a group of AUVs tracking a moving target with varying velocity. For this algorithm, at least one AUV is assumed to be capable of obtaining information about the target, and the communication topology graph of the vehicle is assumed to be undirected connected. Simulations were made using MATLAB to demonstrate the efficiency and effectiveness of the proposed control algorithm, considering a system with three vehicles.

3.3.2. Intervention Missions

There is much more in the underwater environment for AUVs beyond survey missions. Manipulating objects, repairing structures or pipes, recovering black-boxes, extracting samples, among other tasks, make it necessary to have a platform with the capacity of autonomously navigate and perform them, since nowadays these are mostly done by manned or remotely operated vehicles. Researchers have worked in recent years in the design and development of such platforms, which results difficult even for a single Intervention AUV (I-AUV) due to the complexity of the vehicle itself plus the manipulator system. The Girona 500 I-AUV is an example of a single vehicle platform for intervention missions. This vehicle is used to autonomously dock into an adapted subsea panel and perform the intervention task of turning a valve and plugging in/unplugging a connector [140]. The same vehicle was also equipped with a three-fingered gripper and an artificial vision system to locate and recover a black-box [141]. Other projects, such as the Italian national project MARIS [142] have been launched to produce theoretical, simulated and experimental results for intervention AUVs either standalone or for collaborative teams. The aim of the MARIS project was the development of technologies that allow the use of teams of AUVs for intervention missions, in particular: reliable guidance and control, stereovision techniques for object recognition, reliable grasp, manipulation and transportation of objects, coordination and control methods for large object grasp and transportation, high-level mission planning techniques, underwater communication, and the design and realization of prototype systems, allowing experimental demonstrations of integrating the results from the previous objectives. The open-frame fully actuated robotic platform R2 ROV/AUV was used for the MARIS project, and the Underwater Modular Manipulator (UMA); none of them developed within the project. A vision system and a gripper were designed for the autonomous execution of manipulation tasks. Tests were performed to assess the correct integration of all the components, with a success rate of a grasping operation of up 70% [143]. This project was an important achievement in terms of autonomous underwater manipulation, and the theoretical studies for multi-vehicle localization and collaborative underwater manipulation systems will be the next step to be demonstrated in field trials. For collaborative I-AUVs, Simetti et al. [144,145] described a novel cooperative control policy for the transportation of large objects in underwater environments using two manipulator vehicles. The cooperative control algorithm takes into account all mission stages: grasping, transportation, and the final positioning of the shared object by two vehicles. The cooperative transportation of the object is carried out to deal with limitations of acoustic communication, this was achieved successfully by exchanging just the tool frame velocities. A simulation was done, with the UwSim dynamic simulator, using two vehicles of 6 degrees of freedom in order to test the control algorithms. The simulation consisted of completing the following tasks: keeping away from joint limits, keeping the manipulability measure above a certain threshold, maintaining the horizontal attitude of the vehicles, maintaining a fixed distance between the vehicles, reaching the desired goal position. The system managed to accomplish the final objective of the mission successfully, by transporting the object to the desired goal position. Conti et al. [146] proposed an innovative decentralized approach for cooperative mobile manipulation of intervention AUVs. The control architecture deals with the simultaneous control of the vehicles and robotic arms, and the underwater localization. Simulations were made in MATLAB Simulink to test the potential of the system. The cooperative mobile manipulation was performed by four AUVs placed at the four corners of the object and obstacles were introduced as spheres. According to authors, results were very encouraging because the AUV swarm keeps both, the formation during the manipulation phase and the object, during an avoiding phase performed due to the presence of obstacles. Cataldi et al. [147] worked in cooperative control of underwater vehicle-manipulator systems. An architecture is proposed by authors which take into account most of the underwater constraints: uncertainty in the model, low sensor bandwidth, position-only arm control, geometric-only object pose estimation. The simulated system, designed in MATLAB and adapted with SimMechanics, consisted of two AUVs transporting a bar. Results on bar position and applied forces on end effectors provided promising results on its possible real applications. Heshmati-alamdari et al. [148] worked on a similar system. Nonlinear model predictive control approach was proposed for a team of AUVs transporting an object. The model has to deal with the coupled dynamics between the robots and the object. The feedback relies only on each AUV local measurements to deal with communication issues, and no data is exchanged between the robots. A real-time simulation, based on UwSim dynamic simulator and running on the Robot Operating System (ROS), was performed to validate the proposed approach, where the aim for the team of AUVs was to follow a set of pre-defined waypoints while avoiding obstacles within the workspace which was successfully achieved.

A summary of collaborative AUVs missions is presented in Table 6, as well as the potential applications and the strategies proposed in recent years.

Table 6.

Summary on collaborative AUV missions.

3.4. Collaborative AUVs Overview

Nature of underwater environments makes the use of communication systems with high-frequency signals difficult. This due to the rapid attenuation that permits propagation only at very short distances. Acoustic signals have a better performance, but face many challenges such as signal interferences and small bandwidth, which results in the need for time synchronization methods and hence, produce a high latency in the system. Another option is a light-based system, which offers a higher bandwidth but at short/medium ranges. Blue/green light has better propagation in underwater than any other light; but, when the range for communication is increased, the power consumption, weight, and volume of the equipment required also increase.

If the inter-vehicle communication system is good enough in terms of range, bandwidth and rate, range-only/single-beacon can be an effective method for target localization and collaborative navigation of teams of AUVs. Vision-based systems are also an option that has the potential to control AUV formations without the need of relying on inter-vehicle communications, but only if the environmental conditions are favorable for light propagation and sensing.

Collaborative missions are quite difficult to implement in real conditions. Assembling a team of AUVs with the proper technology to overcome localization, navigation, and communication shortcomings results difficult for researchers who have to limit their proposals to numerical simulations. Most of the authors use MATLAB Simulink to perform their simulations and some tools such as the former SimMechanics (now called Simscape Multibody). Another simulation environment commonly used for underwater robotics is the UnderWater Simulator (UWSim) [149]. With those tools, researches are working in pushing the state-of-the-art in terms of control, localization, and navigation algorithms. Within them, machine learning algorithms are gaining quite an attention. They are being employed in different aspects such as navigation [150,151], obstacle avoidance and multi-AUVs formation control.

4. Conclusions

A review of different alternatives for underwater localization, communication, and navigation of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles is addressed in this work. Although Section 2 discusses single-vehicle localization and navigation, the aim of this work is to show that those technologies are being applied to multi-vehicles systems, or can be implemented in the future. Every underwater mission is different and has its own limitations and challenges. For that reason, it is not possible to state which localization or navigation system has the best performance. For a long-range mission (kilometers) an accuracy of tens or hundreds of meters from an inertial-based navigation system can be acceptable, as the main characteristic wanted for it is the long-range capacity. In a small navigation environment, i.e., a docking station or a laboratory tank, there is a need for much better accuracy to avoid collisions with the tank’s walls. In that situation, an SBL/USBL system at an operation frequency of 200 kHz can perform with errors in centimeters range or, if the water conditions are favorable, a visual-based system can perform even better at a lower cost.

Current achievements in the field of collaborative AUVs have been also presented, including communication, collaborative localization and navigation, surveillance, and intervention missions. The use of a hybrid (acoustic and light-based) system is a promising option for the communication of collaborative AUVs. The acoustic sub-system can handle the long-range communications meanwhile the light-based takes care of the inter-vehicle communication where a high rate is critical for collision avoidance. A hybrid system can be an interesting alternative also for collaborative navigation. Acoustic methods can be implemented in a team of AUVs for medium/long-range navigation meanwhile a visual-based method is used to maintain the formation and avoid collisions between the vehicles. In terms of algorithms, machine learning seems to be one of the best approaches to achieve collaborative navigation and to give a team the capacity to perform complex surveillance and intervention missions. Relating to collaborative intervention missions, which mostly have been addressed with numerical simulations, the next step is to test the algorithms in real experiments. Such experimentation can be done in controlled conditions, such as a laboratory tank, where the vehicles would not have to deal with the changing conditions of the sea, so researches can focus on the collaborative task algorithms such as the carrying of an object by two vehicles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-G., A.G.-E., L.G.G.-V., and T.S.-J.; methodology, J.G.-G., A.G.-E, E.C.-U., L.G.G.-V., and T.S.-J.; investigation, J.G.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.-G.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, J.G.-G.; supervision, A.G.-E., E.C.-U., L.G.G.-V., and T.S.-J.; funding acquisition J.A.E.C.; project administration, J.G.-G., A.G.-E., L.G.G.-V., and T.S.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of Tecnologico de Monterrey, in the production of this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from CONACyT for PhD studies of first author (scholarship number 741738).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AFRB | Autonomous Field Robotics Laboratory |

| AHRS | Attitude and Heading Reference System |

| AUV | Autonomous Underwater Vehicle |

| BITAN | Beijing university of aeronautics and astronautics Inertial Terrain-Aided Navigation |

| BK | Bandler and Kohout |

| CRNN | Convolution Recurrent Neural Network |

| DR | Dead-Reckoning |

| DSO | Direct Sparse Odometry |

| DT | Distance Traveled |

| DVL | Doppler Velocity Logger |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| ELC | Extended Loosely Coupled |

| FLS | Forward-Looking SONAR |

| FTPS | Fitting of Two Point Sets |

| GBNN | Glasius Bio-inspired Neural Network |

| GN | Geophysical Navigation |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HSV | Hue Saturation Value |

| I-AUV | Intervention AUV |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INS | Inertial Navigation Systems |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| LBL | Long Baseline |

| LC | Loosely Coupled |

| LCI | Language-Centered Intelligence |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical System |

| NRT | Near-Real-Time |

| NN | Neural Networks |

| PF | Particle Filter |

| PL-SLAM | Point and Line SLAM |

| PMF | Point Mass Filter |

| PS | Pressure Sensor |

| PTAM | Parallel Tracking And Mapping |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square Error |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| ROS | Robot Operating System |

| SBL | Short Baseline |

| SINS | Strapdown Inertial Navigation System |

| SITAN | Sandia Inertial Terrain Aided Navigation |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Location And Mapping |

| SoG | Sum of Gaussian |

| SONAR | Sound Navigation And Ranging |

| SVO | Semi-direct Visual Odometry |

| TAN | Terrain-Aided Navigation |

| TBN | Terrain-Based Navigation |

| TC | Tightly Coupled |

| TERCOM | TERrain COntour-Matching |

| TERPROM | TERrain PROfile Matching |

| TRN | Terrain-Referenced Navigation |

| UKF | Unscented Kalman Filter |

| USBL | Ultra-Short Baseline |

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vehicle |

| VIO | Visual Inertial Odometry |

| VO | Visual Odometry |

References

- Petillo, S.; Schmidt, H. Exploiting adaptive and collaborative AUV autonomy for detection and characterization of internal waves. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2014, 39, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massot-Campos, M.; Oliver-Codina, G. Optical sensors and methods for underwater 3D reconstruction. Sensors 2015, 15, 31525–31557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Song, X.; Li, H. Target recognition and location based on binocular vision system of UUV. Chin. Control Conf. CCC 2015, 2015, 3959–3963. [Google Scholar]

- Ridao, P.; Carreras, M.; Ribas, D.; Sanz, P.J.; Oliver, G. Intervention AUVs: The next challenge. Annu. Rev. Control 2015, 40, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, N.; Matos, A. Minehunting Mission Planning for Autonomous Underwater Systems Using Evolutionary Algorithms. Unmanned Syst. 2014, 2, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Wood, J.; Haworth, C. The detection and disposal of IED devices within harbor regions using AUVs, smart ROVs and data processing/fusion technology. In Proceedings of the 2010 International WaterSide Security Conference, Carrara, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, M. Research on geomagnetic-matching localization algorithm for unmanned underwater vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Information and Automation, Zhangjiajie, China, 20–23 June 2008; pp. 1025–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, J.J.; Bennett, A.A.; Smith, C.M.; Feder, H.J.S. Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Navigation. MIT Mar. Robot. Lab. Tech. Memo. 1998, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, H.; Kelmenson, S.; Mendelsohn, L. Geophysical navigation technologies and applications. In Proceedings of the PLANS 2004 Position Location and Navigation Symposium (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37556), Monterey, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2004; pp. 618–624. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, M.F.; Kaess, M.; Johannsson, H.; Leonard, J.J. Efficient AUV navigation fusing acoustic ranging and side-scan sonar. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 2398–2405. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, J.; Gracias, N.; Ridao, P.; Istenič, K.; Ribas, D. Close-range tracking of underwater vehicles using light beacons. Sensors 2016, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicosevici, T.; Garcia, R.; Carreras, M.; Villanueva, M. A review of sensor fusion techniques for underwater vehicle navigation. In Proceedings of the Oceans ’04 MTS/IEEE Techno-Ocean ’04 (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37600), Kobe, Japan, 9–12 November 2005; pp. 1600–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Paull, L.; Saeedi, S.; Seto, M.; Li, H. AUV navigation and localization: A review. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2014, 39, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Wells, I.; Dickers, G.; Kear, P.; Gong, X. Re-evaluation of RF electromagnetic communication in underwater sensor networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2010, 48, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dosso, S.E.; Sun, D. Motion-compensated acoustic localization for underwater vehicles. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2016, 41, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Zheng, C.; Sun, D. Underwater target localization using long baseline positioning system. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 111, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zheng, C.; Sun, D. Accurate underwater localization using LBL positioning system. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2015-MTS/IEEE Washington, Washington, DC, USA, 19–22 October 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.; Luo, H. Study of underwater positioning based on short baseline sonar system. Int. Conf. Artif. Intell. Comput. Intell. AICI 2009, 2, 343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.M.; Kronen, D. Experimental results of an inexpensive short baseline acoustic positioning system for AUV navigation. Ocean. Conf. Rec. 1997, 1, 714–720. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzi, R.; Monnini, N.; Ridolfi, A.; Allotta, B.; Caiti, A. On field experience on underwater acoustic localization through USBL modems. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2017, Aberdeen, UK, 19–22 June 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Morgado, M.; Oliveira, P.; Silvestre, C. Experimental evaluation of a USBL underwater positioning system. In Proceedings of the ELMAR-2010, Zadar, Croatia, 15–17 September 2010; pp. 485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ding, X.; Lv, P.; Feng, C.; He, B.; Yan, T. USBL positioning system based Adaptive Kalman filter in AUV. In Proceedings of the 2018 OCEANS-MTS/IEEE Kobe Techno-Oceans (OTO), Kobe, Japan, 28–31 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, J.; Morgado, M.; Batista, P.; Oliveira, P.; Silvestre, C. Design and experimental validation of a USBL underwater acoustic positioning system. Sensors 2016, 16, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petillot, Y.R.; Antonelli, G.; Casalino, G.; Ferreira, F. Underwater Robots: From Remotely Operated Vehicles to Intervention-Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2019, 26, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaman, D. TRN history, trends and the unused potential. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/AIAA 31st Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), Williamsburg, VA, USA, 14–18 October 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, J.; Matos, A. Survey on advances on terrain based navigation for autonomous underwater vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2017, 139, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekeli, C. Gravity on Precise, Short-Term, 3-D Free- Inertial Navigation. J. Inst. Navig. 1997, 44, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, M.; Robin, L. High-performance, low cost inertial MEMS: A market in motion! In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Myrtle Beach, SC, USA, 23–26 April 2012; pp. 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Jekeli, C. Precision free-inertial navigation with gravity compensation by an onboard gradiometer. J. Guid. Control. Dyn. 2007, 30, 1214–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, H.; Mendelsohn, L.; Aarons, R.; Mazzola, D. Next generation marine precision navigation system. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2000 Position Location and Navigation Symposium (Cat. No.00CH37062), San Diego, CA, USA, 13–16 March 2000; pp. 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- ISM3D-Underwater AHRS Sensor-Impact Subsea. Available online: http://www.impactsubsea.co.uk/ism3d-2/ (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Underwater 9-axis IMU/AHRS sensor-Seascape Subsea BV. Available online: https://www.seascapesubsea.com/product/underwater-9-axis-imu-ahrs-sensor/ (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Inertial Labs Attitude and Heading Reference Systems (AHRS)-Inertial Labs. Available online: https://inertiallabs.com/products/ahrs/ (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Elipse 2 series-Miniature Inertial Navigation Sensors. Available online: https://www.sbg-systems.com/products/ellipse-2-series/#ellipse2-a_miniature-ahrs (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- DSPRH-Depth and AHRS Sensor | TMI-Orion.Com. Available online: https://www.tmi-orion.com/en/robotics/underwater-robotics/dsprh-depth-and-ahrs-sensor.htm (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- VN-100-VectorNav Technologies. Available online: https://www.vectornav.com/products/vn-100 (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- XSENS-MTi 600-Series. Available online: https://www.xsens.com/products/mti-600-series (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Hurtos, N.; Ribas, D.; Cufi, X.; Petillot, Y.; Salvi, J. Fourier-based Registration for Robust Forward-looking Sonar Mosaicing in Low-visibility Underwater Environments. J. Field Robot. 2014, 32, 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Galarza, C.; Masmitja, I.; Prat, J.; Gomariz, S. Design of obstacle detection and avoidance system for Guanay II AUV. 24th Mediterr. Conf. Control Autom. MED 2016, 5, 410–414. [Google Scholar]

- Braginsky, B.; Guterman, H. Obstacle avoidance approaches for autonomous underwater vehicle: Simulation and experimental results. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2016, 41, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wang, H.; Yuan, J.; Yu, D.; Li, C. An improved recurrent neural network for unmanned underwater vehicle online obstacle avoidance. Ocean Eng. 2019, 189, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LBL Positioning Systems | EvoLogics. Available online: https://evologics.de/lbl#products (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- GeoTag. Available online: http://www.sercel.com/products/Pages/GeoTag.aspx?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI5sqPkY3S5gIV2v_jBx0apwTAEAAYAiAAEgILm_D_BwE (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- MicroPAP Compact Acoustic Positioning System-Kongsberg Maritime. Available online: https://www.kongsberg.com/maritime/products/Acoustics-Positioning-and-Communication/acoustic-positioning-systems/pap-micropap-compact-acoustic-positioning-system/ (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Subsonus | Advanced Navigation. Available online: https://www.advancednavigation.com/product/subsonus?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI5sqPkY3S5gIV2v_jBx0apwTAEAAYASAAEgJNpfD_BwE (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Underwater GPS-Water Linked AS. Available online: https://waterlinked.com/underwater-gps/ (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Batista, P.; Silvestre, C.; Oliveira, P. Tightly coupled long baseline/ultra-short baseline integrated navigation system. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2016, 47, 1837–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilijević, A.; Nad, D.; Mandi, F.; Miškovi, N.; Vukić, Z. Coordinated navigation of surface and underwater marine robotic vehicles for ocean sampling and environmental monitoring. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarda, E.I.; Dhanak, M.R. Launch and Recovery of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle from a Station-Keeping Unmanned Surface Vehicle. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 44, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmitja, I.; Gomariz, S.; Del Rio, J.; Kieft, B.; O’Reilly, T. Range-only underwater target localization: Path characterization. In Proceedings of the Oceans 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, M.; Crasta, N.; Aguiar, A.P.; Pascoal, A.M. Range-Based Underwater Vehicle Localization in the Presence of Unknown Ocean Currents: Theory and Experiments. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallicrosa, G.; Ridao, P. Sum of Gaussian single beacon range-only localization for AUV homing. Annu. Rev. Control 2016, 42, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Tong, J. A passive acoustic positioning algorithm based on virtual long baseline matrix window. J. Navig. 2019, 72, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Sun, M.; Yan, M.; Yang, D. Simulation study of underwater passive navigation system based on gravity gradient. Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. 2004, 5, 3111–3113. [Google Scholar]

- Meduna, D.K. Terrain Relative Navigation for Sensor-Limited Systems with Applications to Underwater Vehicles; Doctor of Philisophy, Standford University,: Stanford, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, E.; Dong, C.; Yang, Y.; Tang, S.; Liu, J.; Gong, G.; Deng, Z. A Robust Solution of Integrated SITAN with TERCOM Algorithm: Weight-Reducing Iteration Technique for Underwater Vehicles’ Gravity-Aided Inertial Navigation System. Navig. J. Inst. Navig. 2017, 64, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hung, J.C. BITAN-II: An improved terrain aided navigation algorithm. IECON Proc. Ind. Electron. Conf. 1996, 3, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Wang, B.; Deng, Z.; Fu, M. A combined matching algorithm for underwater gravity-Aided navigation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, A.; Cai, H.; Yang, H. Algorithm for geomagnetic navigation and its validity evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Computer Science and Automation Engineering, Shanghai, China, 10–12 June 2011; pp. 573–577. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, A. Study on underwater navigation system based on geomagnetic match technique. In Proceedings of the 2009 9th International Conference on Electronic Measurement & Instruments, Beijing, China, 16–19 August 2009; pp. 3255–3259. [Google Scholar]

- Menq, C.H.; Yau, H.; Lai, G. Automated precision measurement of surface profile in CAD-directed inspection. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1992, 8, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Kun, Y.; Tian, C. Study on the underwater geomagnetic navigation based on the integration of TERCOM and K-means clustering algorithm. In Proceedings of the OCEANS’10 IEEE SYDNEY, Sydney, Australia, 24–27 May 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jaulin, L. Isobath following using an altimeter as a unique exteroceptive sensor. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2018, 2331, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, M.; Wilkinson, N.; Powlesland, R. Latest Development of the TERPROM ® Digital Terrain System ( DTS ). In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Monterey, CA, USA, 5–8 May 2008; pp. 219–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Gao, N.; Huang, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J. A novel terrain-aided navigation algorithm combined with the TERCOM algorithm and particle filter. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavasidis, G.; Munafò, A.; Harris, C.A.; Prampart, T.; Templeton, R.; Smart, M.; Roper, D.T.; Pebody, M.; McPhail, S.D.; Rogers, E.; et al. Terrain-aided navigation for long-endurance and deep-rated autonomous underwater vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meduna, D.K.; Rock, S.M.; McEwen, R.S. Closed-loop terrain relative navigation for AUVs with non-inertial grade navigation sensors. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles, Monterey, CA, USA, 1–3 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nootz, G.; Jarosz, E.; Dalgleish, F.R.; Hou, W. Quantification of optical turbulence in the ocean and its effects on beam propagation. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, F.; Pe’Eri, S.; Thein, M.W.; Rzhanov, Y.; Celikkol, B.; Swift, M.R. Position, orientation and velocity detection of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) using an optical detector array. Sensors 2017, 17, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, D.; Lin, M.; Lin, R.; Yang, C. A fast binocular localisation method for AUV docking. Sensors 2019, 19, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, H.; Lin, Y.; Gao, L. Visual navigation for recovering an AUV by another AUV in shallow water. Sensors 2019, 19, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroy-Anieva, J.A.; Rouviere, C.; Campos-Mercado, E.; Salgado-Jimenez, T.; Garcia-Valdovinos, L.G. Modeling and control of a micro AUV: Objects follower approach. Sensors 2018, 18, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prats, M.; Ribas, D.; Palomeras, N.; García, J.C.; Nannen, V.; Wirth, S.; Fernández, J.J.; Beltrán, J.P.; Campos, R.; Ridao, P.; et al. Reconfigurable AUV for intervention missions: A case study on underwater object recovery. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2012, 5, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant-Whyte, H.; Bailey, T. Simultaneous localization and mapping: Part I. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2006, 13, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Song, D. Visual Navigation Using Heterogeneous Landmarks and Unsupervised Geometric Constraints. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, H.; Dames, P.; Kumar, V.; Castellanos, J.A. Autonomous robotic exploration using occupancy grid maps and graph SLAM based on Shannon and Rényi Entropy. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzoli, M.; Forster, C.; Scaramuzza, D. REMODE: Probabilistic, monocular dense reconstruction in real time. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 2609–2616. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, C.; Schuster, M.J.; Hirschmüller, H.; Suppa, M. Stereo-vision based obstacle mapping for indoor/outdoor SLAM. IEEE Int. Conf. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2014, 1846–1853. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.D.; Istenič, K.; Gracias, N.; Palomeras, N.; Campos, R.; Vidal, E.; García, R.; Carreras, M. Autonomous underwater navigation and optical mapping in unknown natural environments. Sensors 2016, 16, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomer, A.; Ridao, P.; Ribas, D. Multibeam 3D underwater SLAM with probabilistic registration. Sensors 2016, 16, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, C.; Singh, H. Consistency based error evaluation for deep sea bathymetric mapping with robotic vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 May 2006; pp. 3568–3574. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ojeda, R.; Moreno, F.A.; Zuñiga-Noël, D.; Scaramuzza, D.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. PL-SLAM: A Stereo SLAM System Through the Combination of Points and Line Segments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2019, 35, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Lin, Y. Application of a Real-Time Visualization Method of AUVs in Underwater Visual Localization. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; Moras, J.; Trouvé-Peloux, P.; Creuze, V.; Dégez, D. The Aqualoc Dataset: Towards Real-Time Underwater Localization from a Visual-Inertial-Pressure Acquisition System. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.07076. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, B.; Rahman, S.; Kalaitzakis, M.; Cain, B.; Johnson, J.; Xanthidis, M.; Karapetyan, N.; Hernandez, A.; Li, A.Q.; Vitzilaios, N.; et al. Experimental Comparison of Open Source Visual-Inertial-Based State Estimation Algorithms in the Underwater Domain; IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS): Macau, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Allotta, B.; Chisci, L.; Costanzi, R.; Fanelli, F.; Fantacci, C.; Meli, E.; Ridolfi, A.; Caiti, A.; Di Corato, F.; Fenucci, D. A comparison between EKF-based and UKF-based navigation algorithms for AUVs localization. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2015-Genova, Genoa, Italy, 18–21 May 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Sun, F.; Yang, L.; Chen, M.; Li, Y. Alignment calibration of IMU and Doppler sensors for precision INS/DVL integrated navigation. Optik (Stuttg) 2015, 126, 3872–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Pasquali, M.; Pastore, M. Performance analysis of an inertial navigation algorithm with DVL auto-calibration for underwater vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2014 DGON Inertial Sensors and Systems (ISS), Karlsruhe, Germany, 16–17 September 2014; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Li, J.; Zhou, G.; Li, Q. Adaptive Kalman filtering with recursive noise estimator for integrated SINS/DVL systems. J. Navig. 2015, 68, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, B.; Deng, Z.; Fu, M. INS/DVL/PS Tightly Coupled Underwater Navigation Method with Limited DVL Measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 2994–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A.; Klein, I.; Katz, R. Inertial navigation system/doppler velocity log (INS/DVL) fusion with partial dvl measurements. Sensors 2017, 17, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shi, H.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Tong, J. AUV positioning method based on tightly coupled SINS/LBL for underwater acoustic multipath propagation. Sensors 2016, 16, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. AUV underwater positioning algorithm based on interactive assistance of SINS and LBL. Sensors 2016, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanilla, A.; Reyes, S.; Garcia, M.; Mercado, D.; Lozano, R. Autonomous navigation for unmanned underwater vehicles: Real-time experiments using computer vision. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ji, D.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y. A Multi-Model EKF Integrated Navigation Algorithm for Deep Water AUV. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, D.; Miller, P.A.; Farrell, J.A. Underwater Inertial Navigation with Long Baseline Transceivers: A Near-Real-Time Approach. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; Creuze, V.; Moras, J.; Trouvé-Peloux, P. AQUALOC: An underwater dataset for visual–inertial–pressure localization. Int. J. Rob. Res. 2019, 38, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autonomous Fiel Robotic Laboratory-Datasets. Available online: https://afrl.cse.sc.edu/afrl/resources/datasets/ (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Hwang, J.; Bose, N.; Fan, S. AUV Adaptive Sampling Methods: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, N.; Bowen, A.; Ware, J.; Pontbriand, C.; Tivey, M. An integrated, underwater optical/acoustic communications system. In Proceedings of the OCEANS’10 IEEE SYDNEY, Sydney, Australia, 24–27 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovic, M.; Beaujean, P.-P.J. Acoustic Communication. In Springer Handbook of Ocean Engineering; Dhanak, M.R., Xiros, N.I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 359–386. ISBN 978-3-319-16649-0. [Google Scholar]

- 920 Series ATM-925-Acoustic Modems-Benthos. Available online: http://www.teledynemarine.com/920-series-atm-925?ProductLineID=8 (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Micromodem: Acoustic Communications Group. Available online: https://acomms.whoi.edu/micro-modem (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- LinkQuest. Available online: http://www.link-quest.com/html/uwm1000.htm (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- 48/78 Devices | EvoLogics. Available online: https://evologics.de/acoustic-modem/48-78 (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Mats 3G, Underwater Acoustics-Sercel. Available online: http://www.sercel.com/products/Pages/mats3g.aspx (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- L3Harris | Acoustic Modem GPM300. Available online: https://www.l3oceania.com/mission-systems/undersea-communications/acoustic-modem.aspx (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Micron Modem | Tritech | Outstanding Performance in Underwater Technology. Available online: https://www.tritech.co.uk/product/micron-data-modem (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- M64 Acoustic Modem for Wireless Underwater Communication. Available online: https://bluerobotics.com/store/comm-control-power/acoustic-modems/wl-11003-1/ (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Yan, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Yang, Z.; Chen, T.; Xu, J. Polar cooperative navigation algorithm for multi-unmanned underwater vehicles considering communication delays. Sensors 2018, 18, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giodini, S.; Binnerts, B. Performance of acoustic communications for AUVs operating in the North Sea. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Yu, S.; Yan, Y. Formation control of multiple underwater vehicles subject to communication faults and uncertainties. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 82, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A.; DiLeo, N.; Fregene, K. Ieee Decentralized Model Predictive Control for UUV Collaborative Missions. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2017-Anchorage, Anchorage, AK, USA, 18–21 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hallin, N.J.; Horn, J.; Taheri, H.; O’Rourke, M.; Edwards, D. Message anticipation applied to collaborating unmanned underwater vehicles. In Proceedings of the OCEANS’11 MTS/IEEE KONA, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 19–22 September 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Beidler, G.; Bean, T.; Merrill, K.; O’Rourke, M.; Edwards, D. From language to code: Implementing AUVish. In Proceedings of the UUST07, Kos, Greece, 7–9 May 2007; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rajala, A.; O’Rourke, M.; Edwards, D.B. AUVish: An application-based language for cooperating AUVs. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2006, Boston, MA, USA, 18–21 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, J.; Alves, J.; Green, D.; Zappa, G.; Nissen, I.; McCoy, K. The JANUS underwater communications standard. Underw. Commun. Networking, UComms 2014, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Petroccia, R.; Alves, J.; Zappa, G. Fostering the use of JANUS in operationally-relevant underwater applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Third Underwater Communications and Networking Conference (UComms), Lerici, Italy, 30 August–1 September 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.; Furfaro, T.; Lepage, K.; Munafo, A.; Pelekanakis, K.; Petroccia, R.; Zappa, G. Moving JANUS forward: A look into the future of underwater communications interoperability. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Petroccia, R.; Alves, J.; Zappa, G. JANUS-based services for operationally relevant underwater applications. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2017, 42, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, K.; Djapic, V.; Ouimet, M. JANUS: Lingua Franca. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, T.F.; Karp, S. The Role of Blue/Green Laser Systems in Strategic Submarine Communications. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1980, 28, 1602–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschell, J.J.; Giannaris, R.J.; Stotts, L. The Autonomous Data Optical Relay Experiment: First two way laser communication between an aircraft and submarine. In Proceedings of the National Telesystems Conference, NTC IEEE 1992, Washington, DC, USA, 19–20 May 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Enqi, Z.; Hongyuan, W. Research on spatial spreading effect of blue-green laser propagation through seawater and atmosphere. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on E-Business and Information System Security, Wuhan, China, 23–24 May 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha, R.S.; Awasthi, R.L.; Santhanakrishnan, T. Design and analysis of a laser communication link between an underwater body and an air platform. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Next Generation Intelligent Systems (ICNGIS), Kottayam, India, 1–3 September 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cossu, G.; Corsini, R.; Khalid, A.M.; Balestrino, S.; Coppelli, A.; Caiti, A.; Ciaramella, E. Experimental demonstration of high speed underwater visible light communications. In Proceedings of the 2013 2nd International Workshop on Optical Wireless Communications (IWOW), Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 21–21 October 2013; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Luqi, L. Utilization and risk of undersea communications. In Proceedings of the Ocean MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yue, L.; Wang, L.; Jia, H.; Zhou, J. Discrete-time coordinated control of leader-following multiple AUVs under switching topologies and communication delays. Ocean Eng. 2019, 172, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichuan, Z.; Jingxiang, F.; Tonghao, W.; Jian, G.; Ru, Z. A new algorithm for collaborative navigation without time synchronization of multi-UUVS. Ocean. Aberdeen 2017, 2017, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Xu, D.; Chen, T.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Leader-follower formation control of UUVs with model uncertainties, current disturbances, and unstable communication. Sensors 2018, 18, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Y.; Yu, J. Adaptive consensus tracking control for multiple autonomous underwater vehicles with uncertain parameters. ICIC Express Lett. 2019, 13, 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Teck, T.Y.; Chitre, M.; Hover, F.S. Collaborative bathymetry-based localization of a team of autonomous underwater vehicles. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 2014, 2475–2481. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.T.; Gao, R.; Chitre, M. Cooperative path planning for range-only localization using a single moving beacon. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2014, 39, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, D.; Indiveri, G.; Parlangeli, G. Multi-vehicle relative localization based on single range measurements. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 28, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylog, J.G.; Wettergren, T.A. A ROC-Based approach for developing optimal strategies in UUV search planning. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 43, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, B. An adaptive prediction target search algorithm for multi-AUVs in an unknown 3D environment. Sensors 2018, 18, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, S.; Zhu, Y. A Multi-AUV Searching Algorithm Based on Neuron Network with Obstacle. Int. Symp. Auton. Syst. 2019, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bing Sun, D.Z. Complete Coverage Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Path Planning Based on Glasius Bio-Inspired Neural Network Algorithm for Discrete and Centralized Programming. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2019, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, D. Coordinated Target Tracking Strategy for Multiple Unmanned Underwater Vehicles with Time Delays. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 10348–10357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomeras, N.; Peñalver, A.; Massot-Campos, M.; Negre, P.L.; Fernández, J.J.; Ridao, P.; Sanz, P.J.; Oliver-Codina, G. I-AUV docking and panel intervention at sea. Sensors 2016, 16, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, D.; Ridao, P.; Turetta, A.; Melchiorri, C.; Palli, G.; Fernandez, J.J.; Sanz, P.J. I-AUV Mechatronics Integration for the TRIDENT FP7 Project. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 2583–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, G.; Caccia, M.; Caselli, S.; Melchiorri, C.; Antonelli, G.; Caiti, A.; Indiveri, G.; Cannata, G.; Simetti, E.; Torelli, S.; et al. Underwater intervention robotics: An outline of the Italian national project Maris. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2016, 50, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simetti, E.; Wanderlingh, F.; Torelli, S.; Bibuli, M.; Odetti, A.; Bruzzone, G.; Rizzini, D.L.; Aleotti, J.; Palli, G.; Moriello, L.; et al. Autonomous Underwater Intervention: Experimental Results of the MARIS Project. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 43, 620–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simetti, E.; Casalino, G.; Manerikar, N.; Sperinde, A.; Torelli, S.; Wanderlingh, F. Cooperation between autonomous underwater vehicle manipulations systems with minimal information exchange. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2015-Genova, Genoa, Italy, 18–21 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simetti, E.; Casalino, G. Manipulation and Transportation with Cooperative Underwater Vehicle Manipulator Systems. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2017, 42, 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, R.; Meli, E.; Ridolfi, A.; Allotta, B. An innovative decentralized strategy for I-AUVs cooperative manipulation tasks. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2015, 72, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, E.; Chiaverini, S.; Antonelli, G. Cooperative Object Transportation by Two Underwater Vehicle-Manipulator Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 26th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Zadar, Croatia, 19–22 June 2018; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati-alamdari, S.; Karras, G.C.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. A Distributed Predictive Control Approach for Cooperative Manipulation of Multiple Underwater Vehicle Manipulator Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 4626–4632. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, M.; Perez, J.; Fernandez, J.J.; Sanz, P.J. An open source tool for simulation and supervision of underwater intervention missions. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 2577–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Alvarado, R.; García-Valdovinos, L.G.; Salgado-Jiménez, T.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Fonseca-Navarro, F. Neural network-based self-tuning PID control for underwater vehicles. Sensors 2016, 16, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Valdovinos, L.G.; Fonseca-Navarro, F.; Aizpuru-Zinkunegi, J.; Salgado-Jiménez, T.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Cruz-Ledesma, J.A. Neuro-Sliding Control for Underwater ROV’s Subject to Unknown Disturbances. Sensors 2019, 19, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).