Enterprises’ Servitization in the First Decade—Retrospective Analysis of Back-End and Front-End Challenges †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

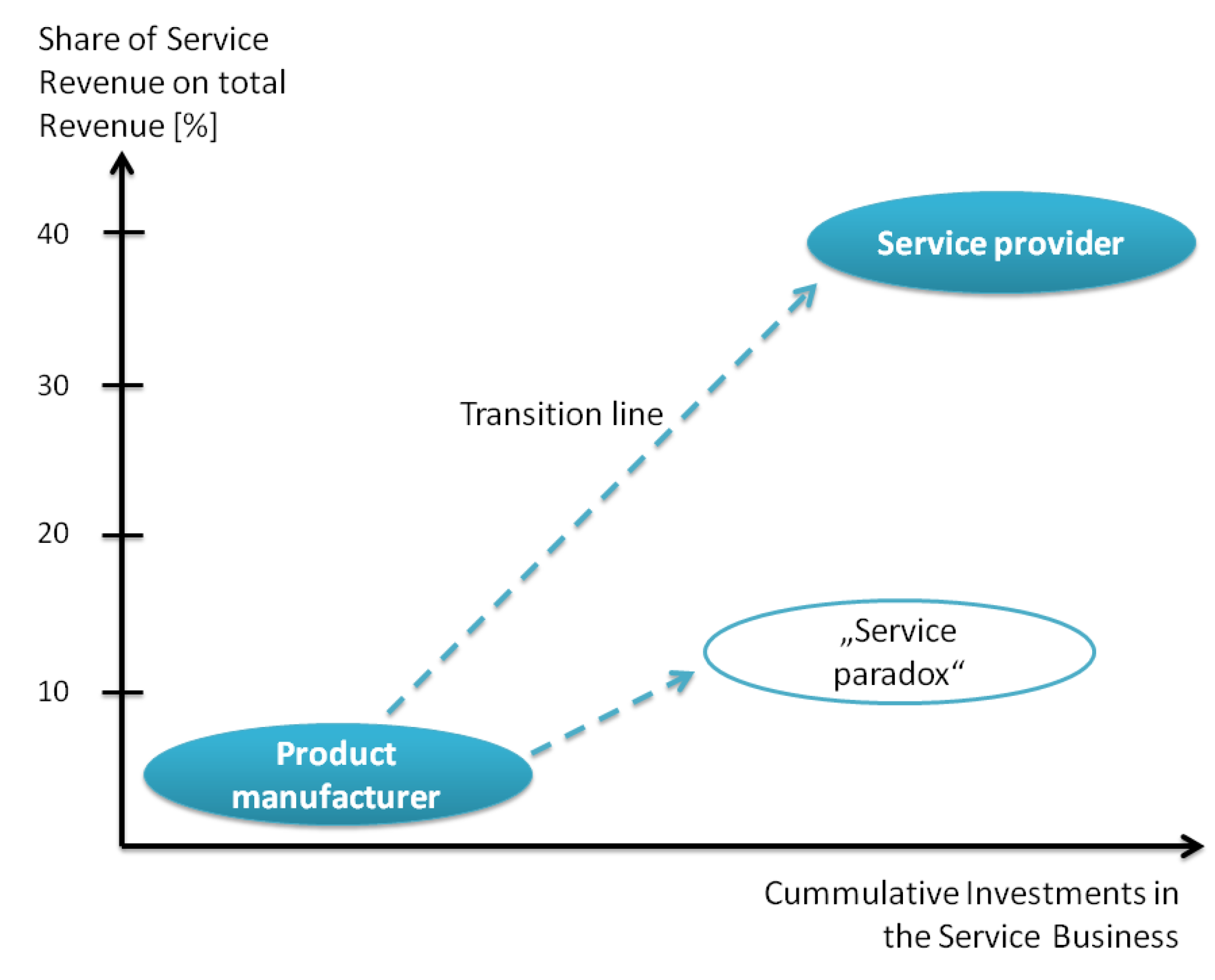

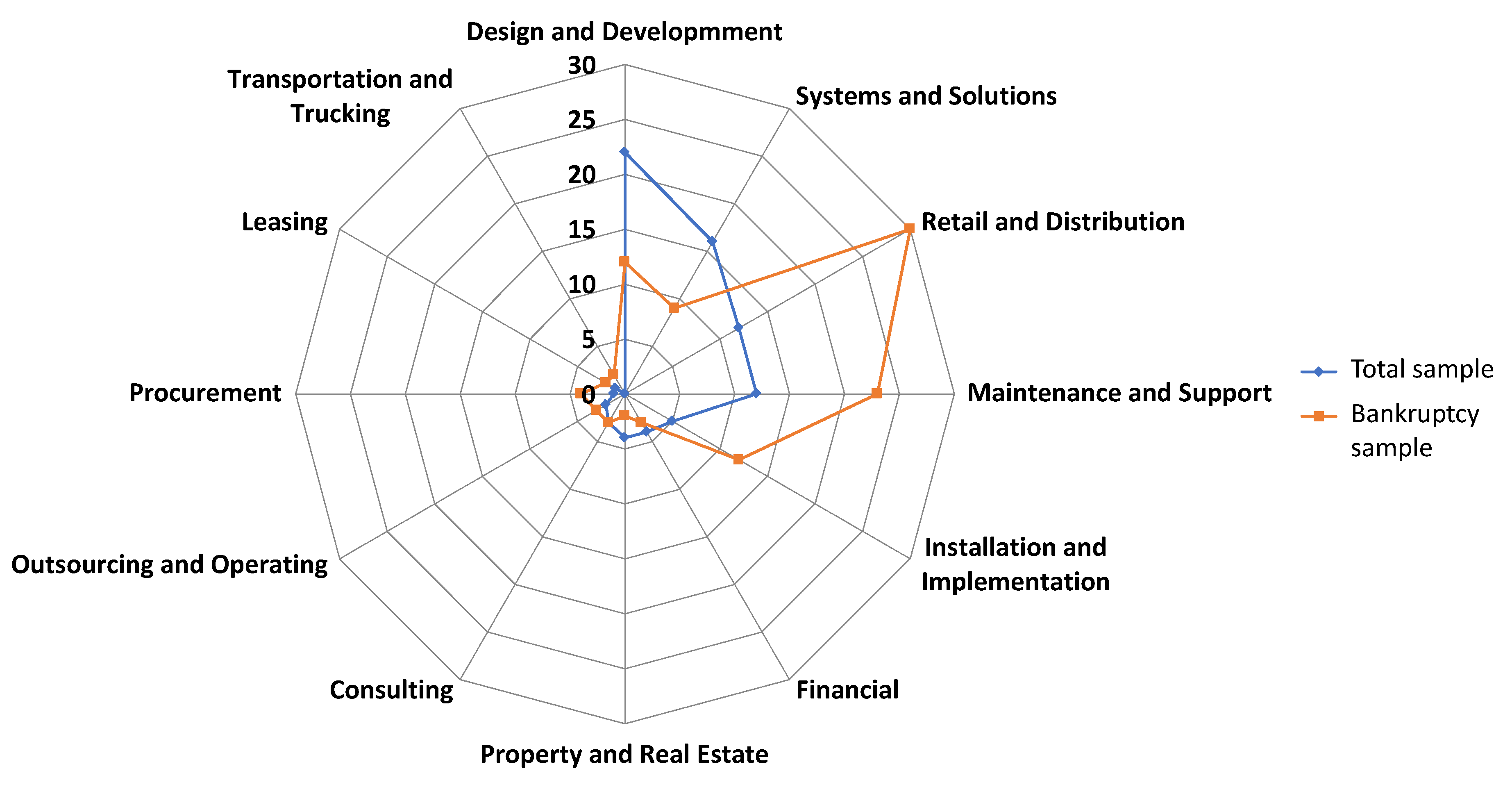

1.1. The Service Paradox

1.2. Management Issues

1.3. Classification of Challenges

2. Back-End Challenges

2.1. Organizational Structure

2.2. Costs and Infrastructure Issues

2.3. Supplier Relationships

3. Front-End Challenges

3.1. Derivation and Assessment

3.2. Pricing

3.3. Shifting Risks

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frank, A.G.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Ayala, N.F.; Ghezzi, A. Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product firms: A business model innovation perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo-Basáez, M.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O.F. Uncovering Productivity Gains of Digital and Green Servitization: Implications from the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raddats, C.; Kowalkowski, C.; Benedettini, O.; Burton, J.; Gebauer, H. Servitization: A contemporary thematic review of four major research streams. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servitization and Digitalization in Manufacturing: The Influence on Firm Performance|Emerald Insight. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JBIM-12-2018-0400/full/html (accessed on 9 November 2019).

- Silva, L.M.; Viagi, A.F.; Giacaglia, G.E.O. The servitization in industry 4.0, facing challenges and tendencies. Eng. Res. Tech. Rep. 2018, 9, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczor, S.; Kryvinska, N.; Strauss, C. Pitfalls in Servitization and Managerial Implications. In Proceedings of the Global Conference on Services Management (GLOSERV 2017), Volterra, Italy, 3–7 October 2017; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Adrodegari, F.; Saccani, N. Business models for the service transformation of industrial firms. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlborg, P.; Kindström, D.; Kowalkowski, C. The evolution of service innovation research: A critical review and synthesis. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Lee, S. Strategic planning using service roadmaps. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellal, F.; Gallouj, F. The productivity challenge in services: Measurement and strategic perspectives. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenonen, S.; Ahvenniemi, O.; Martinsuo, M. Image risks of servitization in collaborative service deliveries. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 1307–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaccini, M.; Saccani, N.; Pezzotta, G.; Burger, T.; Ganz, W. Service development in product-service systems: A maturity model. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Bustinza, O.F.; Shi, V.G.; Baldwin, J.; Ridgway, K. Servitization: Revisiting the state-of-the-art and research priorities. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Benedettini, O.; Kay, J.M. The servitization of manufacturing: A review of literature and reflection on future challenges. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2009, 20, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neely, A. The servitization of manufacturing: An analysis of global trends. In Proceedings of the 14th European Operations Management Association Conference, Ankara, Turkey, 17–20 June 2007; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, R.; Kallenberg, R. Managing the transition from products to services. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2003, 14, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services. Eur. Manag. J. 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, T.; Lightfoot, H.W. Servitization of the manufacturing firm: Exploring the operations practices and technologies that deliver advanced services. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 34, 2–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Evans, S.; Neely, A.; Greenough, R.; Peppard, J.; Roy, R.; Shehab, E.; Braganza, A.; Tiwari, A.; et al. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2007, 221, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basner, K.; Frandsen, T.; Raja, J.Z. Creating Markets for Servitization: Exploring Qualification Processes, Devices and Agencements. In Academy of Management; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2017, p. 15596. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, M.; Peng, F. The increasing service intensity of European manufacturing. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 1686–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, M.H.; Davies, P.; Ng, I.C.L. Two strands of servitization: A thematic analysis of traditional and customer co-created servitization and future research directions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, V. Product services: From a service supporting the product to a service supporting the client. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2001, 16, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, V. Service strategies within the manufacturing sector: Benefits, costs and partnership. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2001, 12, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tether, B.; Bascavusoglu-Moreau, E. Servitization-the extent of and motivation for service provision amongst UK based manufacturers. AIM Res. Work. Pap. Ser. 2011. Available online: http://ukirc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Tether_servitization1.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2011).

- Velamuri, V.K.; Neyer, A.-K.; Möslein, K.M. Hybrid value creation: A systematic review of an evolving research area. J. Für Betr. 2011, 61, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H.; Fleisch, E.; Friedli, T. Overcoming the Service Paradox in Manufacturing Companies. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastalli, I.V.; Van Looy, B. Servitization: Disentangling the impact of service business model innovation on manufacturing firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowalkowski, C.; Gebauer, H.; Kamp, B.; Parry, G. Servitization and deservitization: Overview, concepts, and definitions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A. Exploring the financial consequences of the servitization of manufacturing. Oper. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visnjic, I.; Wiengarten, F.; Neely, A. Only the brave: Product innovation, service business model innovation, and their impact on performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makri, C.; Neely, A. Barriers and Facilitators to Incident Reporting in Servitized Manufacturers. 2017. Available online: https://cambridgeservicealliance.eng.cam.ac.uk/resources/Downloads/Monthly%20Papers/2017JulyPaperCMIncidentReporting.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Kowalkowski, C.; Gebauer, H.; Oliva, R. Service growth in product firms: Past, present, and future. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Brady, T.; Hobday, M. Organizing for solutions: Systems seller vs. systems integrator. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez, V.; Bastl, M.; Kingston, J.; Evans, S. Challenges in transforming manufacturing organisations into product-service providers. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 21, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez, V.; Neely, A.; Velu, C.; Leinster-Evans, S.; Bisessar, D. Exploring the journey to services. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, R.; Plessis, J. du Servitization: Developing a business model to translate corporate strategy into strategic projects. In Proceedings of the 2011 Proceedings of PICMET ’11: Technology Management in the Energy Smart World (PICMET), Portland, OR, USA, 31 July–4 August 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, R.; Benade, S. Servitization: An integrated strategic and operational systems framework. In Proceedings of the Management of Engineering & Technology (PICMET), 2014 Portland International Conference, Kanazawa, Japan, 27–31 July 2014; pp. 3272–3280. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M.; Malek, W.A.; Levitt, R.E. Executing Your Strategy: How to Break It Down and Get It Done. Available online: https://hbr.org/product/executing-your-strategy-how-to-break-it-down-and-get-it-done/9564-HBK-ENG (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Brax, S. A manufacturer becoming service provider—Challenges and a paradox. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2005, 15, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brax, S.A.; Jonsson, K. Developing integrated solution offerings for remote diagnostics: A comparative case study of two manufacturers. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2009, 29, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brax, S.A.; Visintin, F. Meta-model of servitization: The integrative profiling approach. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoto, S.; Brax, S.A.; Kohtamäki, M. Critical meta-analysis of servitization research: Constructing a model-narrative to reveal paradigmatic assumptions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, C.; Bazoun, H.; Zacharewicz, G.; Ducq, Y.; Boye, H. Information models and transformation principles applied to servitization of manufacturing and service systems design. In Proceedings of the 2014 2nd International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development (MODELSWARD), Lisbon, Portugal, 7–9 January 2014; pp. 657–665. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, R.; Benade, S. The development of a generic servitization systems framework. Technol. Soc. 2015, 43, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, Z.; Inohara, T.; Kamoshida, A. The Servitization of Manufacturing: An Empirical Case Study of IBM Corporation. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 4, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, Z.; Kamoshida, A.; Inohara, T. Servitization of Business: An Exploratory Case Study of Customer Perspective. In The 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management in Organizations; Springer Proceedings in Complexity; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-94-007-7286-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Banerji, S. Challenges of servitization: A systematic literature review. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 65, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finne, M.; Brax, S.; Tanskanen, M. Ghosts from the Past: Path-Dependent Effects on Servitisation. Strateg. Chang. Future Ind. Serv. Bus. Tamp. Univ. Technol. 2015, 106–123. Available online: https://tutcris.tut.fi/portal/files/4274023/strategic_change_towards_future_industrial_service_business.pdf#page=115 (accessed on 14 December 2015).

- Baines, T.; Shi, V.G. A Delphi study to explore the adoption of servitization in UK companies. Prod. Plan. Control 2015, 26, 1171–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niemi, A.; Burén, M. Business Model Generation for a Product-Service System: A Case Study. 2012. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1021857 (accessed on 15 January 2015).

- Barnett, N.J.; Parry, G.; Saad, M.; Newnes, L.B.; Goh, Y.M. Servitization: Is a Paradigm Shift in the Business Model and Service Enterprise Required? Strateg. Chang. 2013, 22, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batista, L.; Davis-Poynter, S.; Ng, I.; Maull, R. Servitization through outcome-based contract—A systems perspective from the defence industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benedettini, O.; Neely, A.; Swink, M. Why do servitized firms fail? A risk-based explanation. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 946–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedettini, O.; Swink, M.; Neely, A. Firm’s Characteristics and Servitization Performance: A Bankruptcy Perspective. Univ. Camb. Camb. Serv. Alliance Work. Pap. 2013, 1–11. Available online: https://cambridgeservicealliance.eng.cam.ac.uk/resources/Downloads/Monthly%20Papers/2013MayAlliancePaper_BankruptcyPerspective.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2013).

- Bennett, D. Future challenges for manufacturing. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2014, 25, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdeli, A.Z.; Bustinza, O.F.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Baines, T. Network positioning and risk perception in servitization: Evidence from the UK road transport industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2169–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burton, J.; Story, V.; Zolkiewski, J.; Raddats, C.; Baines, T.S.; Medway, D. Identifying Tensions in the Servitized Value Chain. Res. Technol. Manag. 2016, 59, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bustinza, O.F.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Baines, T.; Elliot, C. Servitization and Competitive Advantage: The Importance of Organizational Structure and Value Chain Position. Res. Technol. Manag. 2015, 58, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, A. Moving base into high-value integrated solutions: A value stream approach. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2004, 13, 727–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozet, M.; Milet, E. Should everybody be in services? The effect of servitization on manufacturing firm performance. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2017, 26, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinges, V.; Urmetzer, F.; Martinez, V.; Zaki, M.; Neely, A. The Future of Servitization: Technologies That Will Make a Difference. Camb. Serv. Alliance Exec. Brief. Pap. 2015. Available online: https://cambridgeservicealliance.eng.cam.ac.uk/resources/Downloads/Monthly%20Papers/150623FutureTechnologiesinServitization.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2015).

- Gotsch, M.; Hipp, C.; Erceg, P.J.; Weidner, N. The Impact of Servitization on Key Competences and Qualification Profiles in the Machine Building Industry. In Servitization in Industry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 315–330. ISBN 978-3-319-06934-0. [Google Scholar]

- Grubic, T. Servitization and remote monitoring technology: A literature review and research agenda. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2014, 25, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Neely, A. Case Studies: Analysing the Effects of Social Capital on Risks Taken by Suppliers in Outcome-Based Contracts; Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert, R.; McFarlane, D.; Neely, A. The Impact of Contract Type on Service Provider Information Requirements. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2012, 3, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Rust, R.T. Customer Satisfaction, Productivity, and Profitability: Differences Between Goods and Services. Mark. Sci. 1997, 16, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Neely, A. Barriers of Servitization: Results of a Systematic Literature Review. Framew. Anal. 2013, 189. Available online: https://scholar.googleusercontent.com/scholar?q=cache:HyqKpHj-cZEJ:scholar.google.com/+Barriers+of+servitization:+Results+of+a+systematic+literature+review&hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0,5&as_vis=1 (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Jovanovic, M.; Visnjic, I.; Wiengarten, F. One Step at A Time: Sequence and Dynamics of Service Capability Configuration in Product Firms. 2018. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1204140&dswid=-3696 (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Huikkola, T.; Kohtamäki, M.; Rabetino, R. Resource Realignment in Servitization. Res. Technol. Manag. 2016, 59, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedettini, O.; Clegg, B.; Kafouros, M.; Neely, A. The Ten Myths of Manufacturing: What Does the Future Hold for UK Manufacturing. Available online: https://research.aston.ac.uk/portal/en/researchoutput/the-ten-myths-of-manufacturing(3eeca435-0aff-49b4-8e03-9d24b2359780).html (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Jovanovic, M.; Engwall, M.; Jerbrant, A. Matching Service Offerings and Product Operations: A Key to Servitization Success. Res. Technol. Manag. 2016, 59, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowski, C.; Windahl, C.; Kindström, D.; Gebauer, H. What service transition? A critical analysis of servitization processes. In Proceedings of the 2013 IMP Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 30 August–2 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente, E.; Vaillant, Y.; Vendrell-Herrero, F. Territorial servitization: Exploring the virtuous circle connecting knowledge-intensive services and new manufacturing businesses. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lammi, M. Emotional service experience toolkit for servitization. Des. J. 2017, 20, S2667–S2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lay, G. Servitization in Industry; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-319-06935-7. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Hernandez, V.; Neely, A.; Ouyang, A.; Burstall, C.; Bisessar, D. Service Business Model Innovation: The digital twin technology. EUROMA Conf. Held Hung. Bp. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, H.; Baines, T.; Smart, P. The servitization of manufacturing: A systematic literature review of interdependent trends. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 1408–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milanzi, D.; Weeks, R. Understanding servitization: A resilience perspective. In Proceedings of the Management of Engineering & Technology (PICMET), 2014 Portland International Conference, Kanazawa, Japan, 27–30 July 2014; pp. 2332–2342. [Google Scholar]

- Hypko, P.; Tilebein, M.; Gleich, R. Benefits and uncertainties of performance-based contracting in manufacturing industries: An agency theory perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 460–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, G. Soniclean—Product-Oriented Servitization. In Manufacturing Servitization in the Asia-Pacific; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 155–173. ISBN 978-981-287-756-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrthianos, V.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Parry, G.; Bustinza, O.F. Firm Profitability During the Servitization Process in the Music Industry. Strateg. Chang. 2014, 23, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, M.; Sellitto, M.; Pereira, G.; Leichtweis Petry, R. A Method to Assess the Performance of After-Sales Service in a Product-Service System. 2011. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266891925_A_method_to_assess_the_performance_of_after-_sales_service_in_a_Product-Service_System (accessed on 26 March 2011).

- Nudurupati, S.S.; Lascelles, D.; Yip, N.; Chan, F.T. Eight challenges of the servitization. In Proceedings of the Spring Servitization Conference, Birmingham, UK, 20–21 May 2013; Volume 2013, pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Opresnik, D.; Zanetti, C.; Taisch, M. Servitization of the Manufacturer’s Value Chain. In Proceedings of the Advances in Production Management Systems. Sustainable Production and Service Supply Chains; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, J.Z.; Johnson, M.; Goffin, K. Uncovering the competitive priorities for servitization: A repertory grid study. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Proceedings, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–11 August 2015; Volume 2015, p. 11988. [Google Scholar]

- Tuli, K.R.; Kohli, A.K.; Bharadwaj, S.G. Rethinking Customer Solutions: From Product Bundles to Relational Processes. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabetino, R.; Kohtamäki, M.; Gebauer, H. Strategy map of servitization. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parry, G.; Tasker, P. Value and Servitization: Creating Complex Deployed Responsive Services. Strateg. Chang. 2014, 23, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddats, C.; Baines, T.; Burton, J.; Story, V.M.; Zolkiewski, J. Motivations for servitization: The impact of product complexity. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 572–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colen, P.J.; Lambrecht, M.R. Product service systems: Exploring operational practices. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccani, N.; Visintin, F.; Rapaccini, M. Investigating the linkages between service types and supplier relationships in servitized environments. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 149, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flunger, R.; Mladenow, A.; Strauss, C. The free-to-play business model. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Information Integration and Web-based Applications & Services; Association for Computing Machinery: Salzburg, Austria, 2017; pp. 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, A.; Saglam, O.; Hacklin, F. Servitization as reinforcement, not transformation. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 662–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, F.X. The Four Things a Service Business Must Get Right. Available online: https://hbr.org/2008/04/the-four-things-a-service-business-must-get-right (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Reinartz, W.; Ulaga, W. How to Sell Services More Profitably. Available online: https://hbr.org/2008/05/how-to-sell-services-more-profitably (accessed on 16 November 2017).

- Shi, V.G.; Baines, T.; Baldwin, J.; Ridgway, K.; Petridis, P.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Uren, V.; Andrews, D. Using gamification to transform the adoption of servitization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 63, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Maull, R.; Ng, I.C.L. Servitization and operations management: A service dominant-logic approach. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 242–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, M.; Araujo, L. Product biographies in servitization and the circular economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turunen, T.; Finne, M. The organisational environment’s impact on the servitization of manufacturers. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtakoski, A. Explaining servitization failure and deservitization: A knowledge-based perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O.F.; Parry, G.; Georgantzis, N. Servitization, digitization and supply chain interdependency. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Parry, G.; Bustinza, O.F.; O’Regan, N. Servitization as a Driver for Organizational Change. Strateg. Chang. 2014, 23, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, S.; Sesana, M.; Gusmeroli, S.; Thoben, K.-D. Requirements for Servitization in Manufacturing Service Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the Advances in Production Management Systems. Sustainable Production and Service Supply Chains; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, I.C.L.; Ding, X. Outcome-Based Contract Performance and Value Co-Production in B2B Maintenance and Repair Service. 2010. Available online: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10036/94184. (accessed on 12 March 2010).

- Zebardast, M.; Taisch, M.; Kremer, G.E.O. An investigation on servitization in manufacturing: Development of a theoretical framework. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE), Bergamo, Italy, 23–25 June 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Breidbach, C.F.; Reefke, H.; Wood, L.C. Investigating the formation of service supply chains. Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giannakis, M. Conceptualizing and managing service supply chains. Serv. Ind. J. 2011, 31, 1809–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvedere, V.; Grando, A.; Bielli, P. A quantitative investigation of the role of information and communication technologies in the implementation of a product-service system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, N. Servitization of the IT Industry: The Cloud Phenomenon. Strateg. Chang. 2014, 23, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopetzky, R.; Günther, M.; Kryvinska, N.; Mladenow, A.; Strauss, C.; Stummer, C. Strategic management of disruptive technologies: A practical framework in the context of voice services and of computing towards the cloud. Int. J. Grid Util. Comput. 2013, 4, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklič, A.; Ćirjaković, J.; Chidlow, A. Exploring the effects of international sourcing on manufacturing versus service firms. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 1193–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.H. Interactions, innovation, and services. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-4256-9. [Google Scholar]

| Approach | Front-End Activities | Back-End Activities |

|---|---|---|

| [51] | Pricing Risk Absorption Complicated Customer Demand | Organizational Culture Close Cooperation |

| [40,42] | Marketing Challenge Product-Design Challenge Communication Challenge Relationship Challenge | Production Challenge Delivery Challenge |

| [35,36] | Delivery of integrated offering Strategic Alignment | Embedded P-S Culture Internal Processes and Capabilities Supplier Relationships |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kryvinska, N.; Kaczor, S.; Strauss, C. Enterprises’ Servitization in the First Decade—Retrospective Analysis of Back-End and Front-End Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2957. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10082957

Kryvinska N, Kaczor S, Strauss C. Enterprises’ Servitization in the First Decade—Retrospective Analysis of Back-End and Front-End Challenges. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(8):2957. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10082957

Chicago/Turabian StyleKryvinska, Natalia, Sebastian Kaczor, and Christine Strauss. 2020. "Enterprises’ Servitization in the First Decade—Retrospective Analysis of Back-End and Front-End Challenges" Applied Sciences 10, no. 8: 2957. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10082957