Conducting an International, Exploratory Survey to Collect Data on Honey Bee Disease Management and Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Disease impact parameters | Weight |

| Very severe | 5 |

| Severe | 4 |

| Moderate | 3 |

| Low impact | 2 |

| No impact | 1 |

3. Results

3.1. Part A. “General Information about the Honey Bee Diseases, the Proper Management of the Hives and the Use of Medicines”

3.2. Part B. “Assessment of Specific Knowledge about the Prevention and Control Measures Adopted for Varroa, AFB and EFB”

3.3. Part C. “The Kind of Assistance Beekeepers Receive, Their Impressions of the Efficacy of Treatments and the Need for New VMPs”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Qin, H.; Wu, J.; Sadd, B.M.; Wang, X.; Evans, J.D.; Peng, W.; Chen, Y. The Prevalence of Parasites and Pathogens in Asian Honeybees Apis cerana in China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zee, R.; Pisa, L.; Andonov, S.; Brodschneider, R.; Charriere, J.; Chlebo, R.; Coffey, M.F.; Crailsheim, K.; Dahle, B.; Gajda, A.; et al. Managed honey bee colony losses in Canada, China, Europe, Israel and Turkey, for the winters of 2008–2009 and 2009–2010. J. Apic. Res. 2012, 51, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, N.A.; Rennich, K.; Wilson, M.E.; Caron, D.M.; Lengerich, E.J.; Pettis, J.S.; Rose, R.; Skinner, J.A.; Tarpy, D.R.; Wilkes, J.T.; et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2012–2013 annual colony losses in the USA: Results from the Bee Informed Partnership. J. Apic. Res. 2014, 53, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, R.; Brodschneider, R.; Brusbardis, V.; Charriere, J.; Chlebo, R.; Coffey, M.F.; Dahle, B.; Drazic, M.M.; Kauko, L.; Kretavicius, J.; et al. Results of international standardised beekeeper surveys of colony losses for winter 2012–2013: Analysis of winter loss rates and mixed effects modelling of risk factors for winter loss. J. Apic. Res. 2014, 53, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.V.; Steinhauer, N.; Rennich, K.; Wilson, M.E.; Tarpy, D.R.; Caron, D.M.; Rose, R.; Delaplane, K.S.; Baylis, K.; Lengerich, E.J.; et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2013–2014 annual colony losses in the USA. Apidologie 2015, 46, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higes, M.; Martin, R.; Meana, A. Nosema ceranae, a new microsporidian parasite in honeybees in Europe. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2006, 92, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Conte, Y.; Ellis, M.; Ritter, W. Varroa mites and honey bee health: Can Varroa explain part of the colony losses? Apidologie 2010, 41, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rortais, A.; Villemant, C.; Gargominy, O.; Rome, Q.; Haxaire, J.; Papachristoforou, A.; Arnold, G. A New Enemy of Honeybees in Europe: The Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina. In Atlas of Biodiversity Risks—From Europe to the Globe, from Stories to Maps; Settele, J., Grabaum, R., Grobelnick, V., Hammen, V., Klotz, S., Penev, L., Kühn, I., Eds.; Atlas of Biodiversity Risk; Pensoft: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2010; p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.J.; Highfield, A.C.; Brettell, L.; Villalobos, E.M.; Budge, G.E.; Powell, M.; Nikaido, S.; Schroeder, D.C. Global Honey Bee Viral Landscape Altered by a Parasitic Mite. Science 2012, 336, 1304–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutinelli, F.; Montarsi, F.; Federico, G.; Granato, A.; Ponti, A.M.; Grandinetti, G.; Ferre, N.; Franco, S.; Duquesnes, V.; Riviere, M.; et al. Detection of Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae.) in Italy: Outbreaks and early reaction measures. J. Apic. Res. 2014, 53, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatridou, D.; Pohl, L.; Tlak Gajger, I.; De Briyne, N.; Bravo, A.; Saunders, J. Mapping the teaching of honeybee veterinary medicine in the European union and European free trade area. Vet. Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettis, J. A scientific note on Varroa destructor resistance to coumaphos in the United States. Apidologie 2004, 35, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkevich, F.D. Detection of amitraz resistance and reduced treatment efficacy in the Varroa Mite, Varroa destructor, within commercial beekeeping operations. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, H.; Brown, M. Is contact colony treatment with antibiotics an effective control for European foulbrood? Bee World 2001, 82, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genersch, E. American Foulbrood in honeybees and its causative agent, Paenibacillus larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, P.; Aumeier, P.; Ziegelmann, B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S96–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisder, S.; Genersch, E. Identification of Candidate Agents Active against N. ceranae Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium Throughput Screening Assay Based on N. ceranae Infected Cultured Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TECA—Technologies and Practices for Small Agricultural Producers. Available online: http://www.fao.org/teca/categories/beekeeping/en/ (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Apicoltura, Produzioni e Patologie Delle Api. Available online: http://www.izslt.it/apicoltura/en/ (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Gray, A.; Adjlane, N.; Arab, A.; Ballis, A.; Brusbardis, V.; Charriere, J.; Chlebo, R.; Coffey, M.F.; Cornelissen, B.; Amaro da Costa, C.; et al. Honey bee colony winter loss rates for 35 countries participating in the COLOSS survey for winter 2018–2019, and the effects of a new queen on the risk of colony winter loss. J. Apic. Res. 2020, 59, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulhanek, K.; Steinhauer, N.; Rennich, K.; Caron, D.M.; Sagili, R.R.; Pettis, J.S.; Ellis, J.D.; Wilson, M.E.; Wilkes, J.T.; Tarpy, D.R.; et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2015–2016 annual colony losses in the USA. J. Apic. Res. 2017, 56, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, R.; Brown, M.; Thompson, H.; Bew, M. Controlling European foulbrood with the shook swarm method and oxytetracycline in the UK. Apidologie 2003, 34, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thompson, H.; Waite, R.; Wilkins, S.; Brown, M.; Bigwood, T.; Shaw, M.; Ridgway, C.; Sharman, M. Effects of European foulbrood treatment regime on oxytetracycline levels in honey extracted from treated honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies and toxicity to brood. Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.; Waite, R.; Wilkins, S.; Brown, M.; Bigwood, T.; Shaw, M.; Ridgway, C.; Sharman, M. Effects of shook swarm and supplementary feeding on oxytetracycline levels in honey extracted from treated colonies. Apidologie 2006, 37, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, G.E.; Barrett, B.; Jones, B.; Pietravalle, S.; Marris, G.; Chantawannakul, P.; Thwaites, R.; Hall, J.; Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Brown, M.A. The occurrence of Melissococcus plutonius in healthy colonies of Apis mellifera and the efficacy of European foulbrood control measures. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 105, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colin, M.; Vandame, R.; Jourdan, P.; Di Pasquale, S. Fluvalinate resistance of Varroa jacobsoni oudemans (Acari: Varroidae) in Mediterranean apiaries of France. Apidologie 1997, 28, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Elzen, P.; Baxter, J.; Spivak, M.; Wilson, W. Amitraz resistance in Varroa: New discovery in North America. Am. Bee J. 1999, 139, 362. [Google Scholar]

- Elzen, P.; Baxter, J.; Spivak, M.; Wilson, W. Control of Varroa jacobsoni oudemans resistant to fluvalinate and amitraz using coumaphos. Apidologie 2000, 31, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, N.; Della Vedova, G. Decline in the proportion of mites resistant to fluvalinate in a population of Varroa destructor not treated with pyrethroids. Apidologie 2002, 33, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.; Brown, M.; Ball, R.; Bew, M. First report of Varroa destructor resistance to pyrethroids in the UK. Apidologie 2002, 33, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stara, J.; Pekar, S.; Nesvorna, M.; Erban, T.; Vinsova, H.; Kopecky, J.; Doskocil, I.; Kamler, M.; Hubert, J. Detection of tau-fluvalinate resistance in the mite Varroa destructor based on the comparison of vial test and PCR-RFLP of kdr mutation in sodium channel gene. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2019, 77, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M.; Mortarino, M.; Formato, G. The nightmare before Christmas: First cases of thymol resistance in Varroa destructor. In Proceedings of the 11th COLOSS Conference, Lukovica, Slovenia, 21–23 October 2015; pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus Gracia, M.; Moreno, C.; Ferrer, M.; Sanz, A.; Angel Peribanez, M.; Estrada, R. Field efficacy of acaricides against Varroa destructor. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171633. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, C. Thymol—Varroa control. Bee Culture—The Magazine of American Beekeeping; Eastern Apicultural Society, 2018. Available online: https://www.beeculture.com (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Mutinelli, F. Veterinary medicinal products to control Varroa destructor in honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera) and related EU legislation—an update. J. Apic. Res. 2016, 55, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Letter/Number | Question, (Type of Question) | Part/Section |

|---|---|---|

| a | In which region are you located? | - |

| b | Select your profession among the following: | - |

| c | How many beehives do you have? | - |

| 1 | What diseases have you already heard about? (Sm) | A |

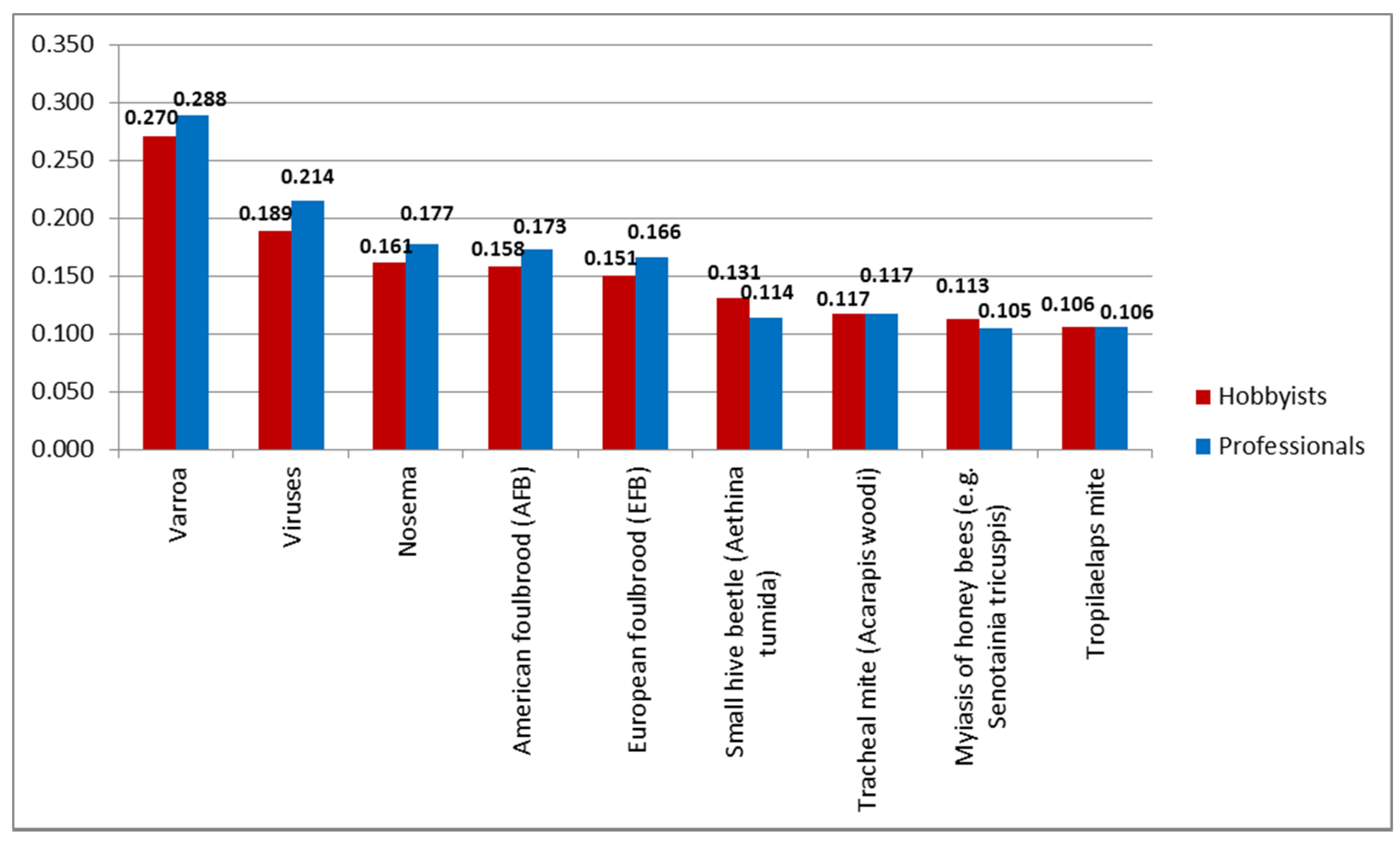

| 2 | Can you give a score to each disease according to its impact on the honeybee health in your apiary? (Sm) | A |

| 3 | Do you have other information you want to share about diseases affecting beekeeping in your country (personal experience, global impact, evolution in the last years, etc.)? (Oe) | A |

| 4 | Do you think that observing good beekeeping practices alone, without the use of active ingredients or medicines, could guarantee the health of your hives (regarding the following diseases)? (Sm) | A |

| 5 | Do you think that veterinary medicines are necessary in apiculture to guarantee the health of your hives (regarding the following diseases)? (Sm) | A |

| 6 | Have you ever seen a Varroa mite? (Cl) | B |

| 7 | Which are the active ingredients you normally use in your apiary in the treatment against Varroa? (Sm) | B |

| 8 | Before treating your hives against Varroa, do you check the level of infestation (mite count)? (Cl) | B |

| 9 | If not yet available, which active ingredients would you like to have in your country as registered and authorized ingredients? (Sm) | B |

| 10 | Have you ever seen brood affected by AFB? (Cl) | B |

| 11 | Are you able to diagnose AFB in your hives? (Cl) | B |

| 12 | How did you diagnose AFB in you hives? (Sm) | B |

| 13 | Which method do you think is the best to manage AFB? (Sm) | B |

| 14 | What product is currently available in your country to treat AFB? (Sm) | B |

| 15 | Do you think the products currently available in your country to treat AFB are effective? (Cl) | B |

| 16 | Have you ever seen brood affected by EFB? (Cl) | B |

| 17 | Are you able to diagnose EFB in your hives? (Cl) | B |

| 18 | How did you diagnose EFB in you hives? (Sm) | B |

| 19 | Which method do you think is the best to manage EFB? (Sm) | B |

| 20 | What product is currently available in your country to treat EFB? (Sm) | B |

| 21 | Do you think the products currently available in your country to treat EFB are effective? (Cl) | B |

| 22 | How did you develop your beekeeping skills? (Sm) | C |

| 23 | Are you well informed about the organization of beekeeping courses/meetings held in your region? (Sm) | C |

| 24 | Do you think you receive appropriate technical assistance for your needs in the apiary treatments? (Sm) | C |

| 25 | What amount of assistance would you need in your apiary for honeybee diseases/apiary management? (Cl) | C |

| 26 | What amount of assistance do you actually get in your apiary for honeybee diseases/apiary management? (Cl) | C |

| 27 | Where do you get assistance about apiary treatments? (Sm) | C |

| 28 | Do you think veterinarians are sufficiently informed on the honeybee diseases and the related treatments? (Sm) | C |

| 29 | Do you think you are well informed about the good beekeeping practices to apply at the apiary level? (Sm) | C |

| 30 | Do you consider effective the veterinary products available in your country to treat the following hive diseases? (Sm) | C |

| 31 | Do you buy veterinary medicines, to treat the following diseases? (Sm) | C |

| 32 | Do you use homemade medicines to treat the following diseases? (Sm) | C |

| 33 | Have you already noticed lack of efficacy of treatments? (Cl) | C |

| 34 | Which active ingredients do you think are no longer effective (e.g., because of resistance)? (Sm) | C |

| 35 | What do you think could be done to improve the efficacy of the available treatments? (Oe) | C |

| 36 | Do you think you need new active ingredients against honeybee diseases? (Cl) | C |

| 37 | Which new active ingredients would you need against Varroa? (Sm) | C |

| 38 | Which new active ingredients would you need against AFB? (Sm) | C |

| 39 | Which new active ingredients would you need against EFB? (Sm) | C |

| 40 | Which new active ingredients would you need against Nosema? (Sm) | C |

| 41 | Which new active ingredients would you need against Tracheal mite (Acarapis woodi)? (Sm) | C |

| 42 | Which new active ingredients would you need against Small hive beetle (Aethina tumida)? (Sm) | C |

| 43 | Which new active ingredients would you need against Tropilaelaps? (Sm) | C |

| 44 | Which new active ingredients would you need against Myiasis of honeybees (e.g., Senotainia tricuspis)? (Sm) | C |

| 45 | Which new active ingredients would you need against any other diseases that were not mentioned in this survey? (Oe) | C |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mezher, Z.; Bubnic, J.; Condoleo, R.; Jannoni-Sebastianini, F.; Leto, A.; Proscia, F.; Formato, G. Conducting an International, Exploratory Survey to Collect Data on Honey Bee Disease Management and Control. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7311. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11167311

Mezher Z, Bubnic J, Condoleo R, Jannoni-Sebastianini F, Leto A, Proscia F, Formato G. Conducting an International, Exploratory Survey to Collect Data on Honey Bee Disease Management and Control. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(16):7311. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11167311

Chicago/Turabian StyleMezher, Ziad, Jernej Bubnic, Roberto Condoleo, Filippo Jannoni-Sebastianini, Andrea Leto, Francesco Proscia, and Giovanni Formato. 2021. "Conducting an International, Exploratory Survey to Collect Data on Honey Bee Disease Management and Control" Applied Sciences 11, no. 16: 7311. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11167311

APA StyleMezher, Z., Bubnic, J., Condoleo, R., Jannoni-Sebastianini, F., Leto, A., Proscia, F., & Formato, G. (2021). Conducting an International, Exploratory Survey to Collect Data on Honey Bee Disease Management and Control. Applied Sciences, 11(16), 7311. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11167311