Abstract

Using mobile augmented reality games in education combines situated and active learning with pleasure. The aim of this research is to analyze the responses expressed by young, middle-aged, and elderly adults about the location-based mobile augmented reality (MAR) games using methods of content analysis, concept maps, and social network analysis (SNA). The responses to questions related to MAR game Ingress were collected from 36 adult players, aged 20–60, from Greece, and subsequently analyzed by means of content analysis, concept maps, and social network analysis. Our findings show that for question 1 (How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences?), there was a differentiation of the answers between age groups with age groups agreeing in pairs, the first two and the last two, while for question 2 (Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge?), there was an overlap in responses of participants among age groups. It was also revealed that the MAR games foster a constructivism approach of learning, as their use learning becomes an active, socially supported process of knowledge construction.

1. Introduction

Games using mobile technologies are complex mechanisms that create multifaceted relationships among players. The potential of LBMGs (location-based mobile games) can be explored in informal education settings [1,2] while addressing wide and diverse fields of research such as mobile learning (m-learning), situated learning, and game-based learning [3]. According to Schito et al. [4], LBMGs provide teachers with methods of conceptualizing classes with long-term learning impact, through ludic, flexible, and innovative approaches. According to a list of Naismith et al. [5], mobile learning tends to be an informal process that occurs over time on the basis of mobility, which is a key property characterizing people’s interactions with technology [6], combining experience of retrieving data through various media. As a consequence, a broad concept of mobility emerges: one that tends to be multifaceted in five interconnected dimensions: mobility in physical space (which refers to people on the move), mobility of technology (which refers to the portability of devices as well as the ability to transfer attention between them), mobility in conceptual space (which refers to mobility from one concept or subject to another), and mobility in social space (which refers to the various contexts in which learners operate and learning is dispersed overtime, and it describes learning as a combined experience that happens through different media and across time).As these five main features of mobility are available to LBMGs, players walk around the city with a portable device, searching for clues and content, and they can socialize with other players and non-players. As a result, mobile learning tends to be an informal method of acquiring information and experience while on the move, which is supported by personal and public technology [6].

The “situated learning model”, mainly developed by Lave and Wenger [7], is based on the relationship with the environment, whether experienced by learners/players through contextual knowledge given by the mobile device or directly exploring the real world. Following this model, learning is a dynamic process characterized by social engagement [5] that necessitates involvement and cooperation, rather than merely a personal acquisition of information. Furthermore, presenting information, and thus understanding, in a real-world sense, gains a lot of impetus.

In his essay “Augmented Learning”, Klopfer [8] argued about the potential of mobile-supported learning in real-world settings, discussing how mobile technology can enhance and augment the learning experience. He theorized that LBMGs are effective means of informal education as well as enforcement of formal education by combining the ability of mobile games to promote interaction and learning outside of formal education activities with the possibility of embedding learning in authentic environments through location-based technologies [9]. This reasoning is supported by Prensky [10], who claims that the combination of enjoyable and immersive entertainment with serious learning is at the heart of digital game-based learning—a combination that the author sees as a way of reaching out to contemporary learners in both formal and informal environments.

Previous research [9,11] found that games could help students learn the English language more effectively and be more motivated in context-aware learning environments. Avouris and Yiannoutsou [12] noted the need for more research into how the architecture of LBMGs affects user experience. The key challenge for designers of LBMGs, according to Alnuaim et al. [13] is to successfully integrate them into authentic educational activities that are important to a student’s work in order to enhance the learning experience. Hung et al. [14] found that spatial learning tools improve students’ spatial perception as well as their academic performance. Slussareff and Boháčková [15] compared the efficacy of knowledge acquisition and interaction from learning by designing and learning by playing LBMGs, and they found a positive impact on knowledge acquisition. Hwang et al. [16] found that an augmented reality mobile gaming approach involving a learning device that detects students’ locations boosts students’ learning attitudes and achievements.

Yet, despite the expansion of these technologies in education, there is a remarkable deficit in our knowledge about what adult learners think and feel about LBMGs. In adult education, quite often, it is more preferable to use qualitative research (with open questions or interviews), because it allows the researcher to delve deeper into this kind of learners’ verbal expressions, which can be more revealing of their attitudes and dispositions about the subject they learn. Furthermore, we still lack knowledge about the way adult learners of LBMGs either build on previous experiences or knowledge they may have or create new ones: we do not know how constructivism works in adult education in which MAR games are used [17,18,19].

One approach to the methodological problems of treating qualitative data of educational research is to use “concept maps” (CM). A concept map can be used to frame a research project, reduce qualitative data, evaluate themes and interconnections in a thesis, and present findings [20]. “A concept map is a schematic device for representing a set of concept meanings embedded in a framework of propositions” [21]. The larger, more inclusive concepts are placed at the top of the concepts hierarchy, with linking to sub-concepts. Concept maps are particularly useful to map out concepts from interviews and open questions. From them emerge the main concepts and sub-concepts which are mentioned repeatedly by the learners, and hence, two needs arise: the need to visualize the relationships among concepts and the need to explore quantitatively their occurrence in the participants’ responses. One possibility to address both these needs is to use networks, but this avenue has never been explored before. SNA was used by McLinden [22] to analyze concepts mentioned by individuals; the data were represented by social networks and analyzed by means of betweenness centrality. While SNA has a long history in humanities and it is also used to evaluate programs [23,24], they have never been used for content analysis before, either for educational research or not.

Thus, from the examination of the literature available so far, the following observations can be made:

- (i)

- Despite the plethora of studies that apply concept maps in education, how adult users assess MAR games (LBMGs in particular) with concept maps has hitherto never been examined or explored. Nor has learning how to play location-based MAR games been examined by using methods of network analysis.

- (ii)

- Constructivism in education in MAR games has poorly investigated so far.

- (iii)

- Networks have never been used to explore the interplay among concepts and sub-concepts as they result from content analysis (not only in education but in general).

- (iv)

- The role of constructivism in education using MAR/LBMGs has been poorly examined.

Hence, by focusing on the MAR game Ingress, the present research addressed these research gaps by concentrating on the following research issues as concerns this particular game:

- (i)

- What are the most important views and attitudes that adult learners have toward Ingress?

- (ii)

- How do these views differ depending on the user’s age?

- (iii)

- What are the advantages of using networks as models for the analysis of adult learners’ concept maps in education?

2. Materials and Methods

Qualitative research methods were applied for data collection in order to assess the educational activity that was carried out centered around the location-based MAR game Ingress, which is selected due to the fact that it is a game suitable for adults and, moreover, it is a widely used open access location-based MAR game, which can be played without ethical concerns by users of all. Two open questions were posed to the participants, which aimed to examine the impact of constructivism through game-based learning:

- Q1: How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences?

- Q2: Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge?

These questions explore the impact of a constructivist approach [25,26] to this adult education research, in which learners learn actively and construct new geography-bound knowledge and experiences by using the location-based MAR game Ingress and how these new knowledge and experiences are based on their prior knowledge.

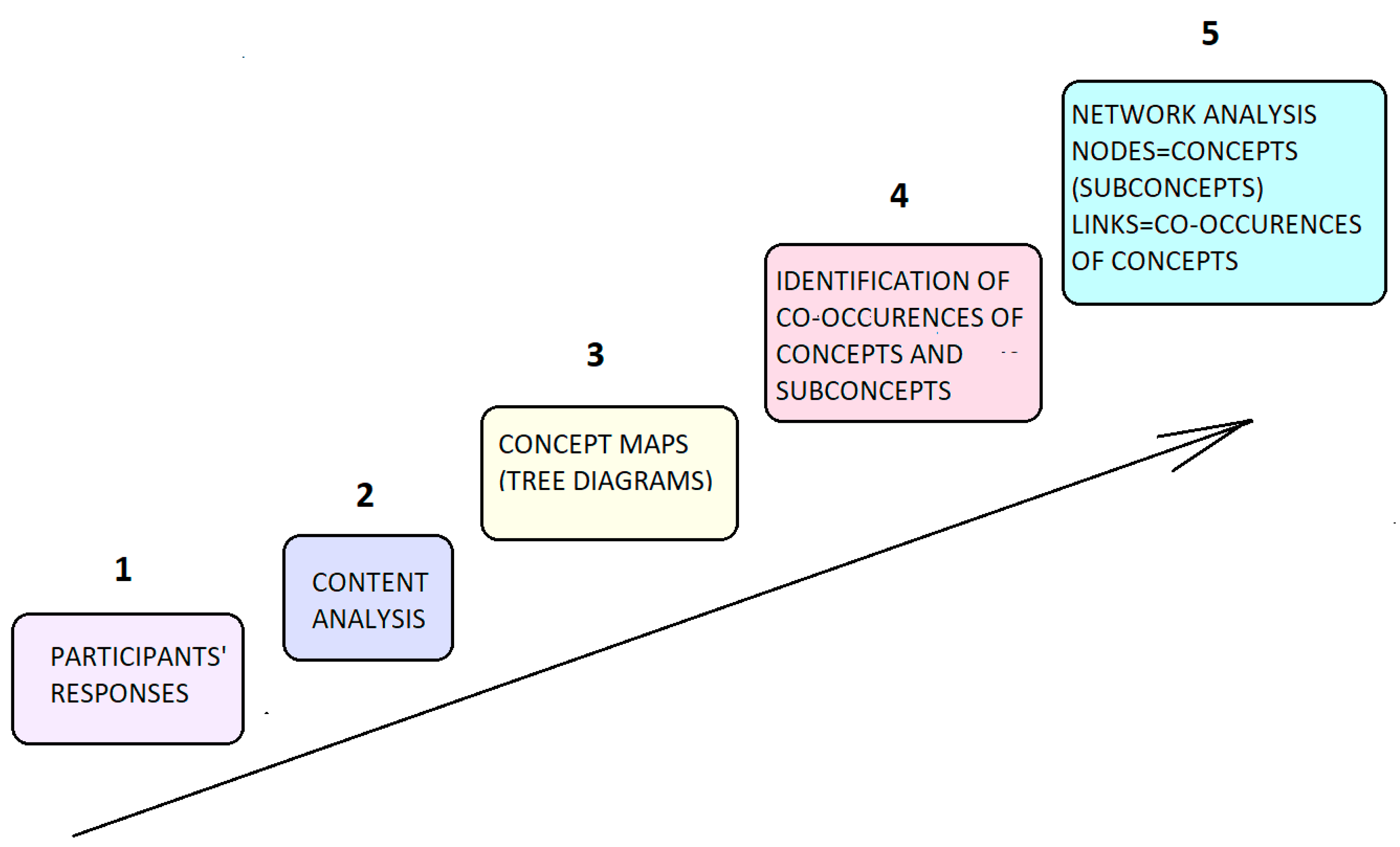

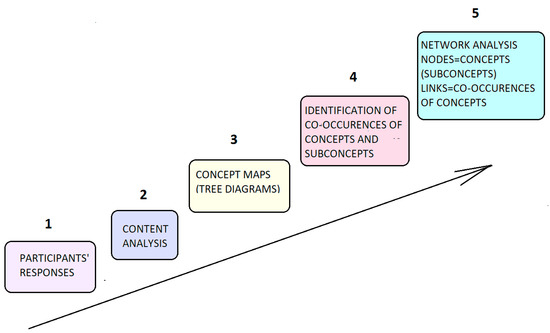

The data obtained from this qualitative research were examined in detail by means of methods of “content analysis”, “concept maps”, and “social network analysis” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The five phases of the research project.

The research involved 36 adult learners in Greece, aged 20 to 60 years old. Participants were trained for 4 h, and the following day, they played Ingress for 3 h. They visited all points of interest (Ingress portals) that were close to their neighborhood during those hours. Various usability issues affected their experience, and all voices (interviews) were recorded and analyzed with the method of content analysis. They were chosen on the basis of four characteristics: (a) they had already been using an Android smartphone, (b) they understood written and spoken English, so they could understand the directions that the game provided them (either written or orally), and (c) they were not familiar with Ingress at all. Of the participants, 19.44% were graduates of secondary education, 8.33% were university students, 44.44% were university graduates, 22.22% held a master’s degree, and 5.55% held a doctoral degree.

The 36 participants of this research were evenly distributed per age group: four age groups were defined with 9 persons in each group and at 10-year intervals: 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, and 50–60. The means and the standard deviations per age group are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age groups with number of participants per group, mean age, and standard deviation.

The research project was articulated in five phases, as shown in Figure 1.

- The first step was the recording of the participants’ responses, after they were trained in the use of Ingress and began using it.

- Their responses were analyzed following methods of content analysis, which is “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” [27]. Content analysis as a method necessitates the use of advanced techniques and is independent of the researcher’s personal authority [27]. Six steps are usually followed in content analyses: unitizing, sampling/coding, data reduction, inferring conclusions, and narrating. What results from this phase is a set of concepts and sub-concepts that correspond to each one of the two questions that were asked.

- Once the main concepts were identified from within the participants’ responses, the concepts and their sub-concepts were articulated in tree diagrams, and thus, they become suitable to create networks of concepts.

- The agreements among participants over a given concept or sub-concept were registered and formed the basis for the construction of networks of concepts: the nodes of networks represent the concepts or sub-concepts, and the links between nodes stand for the agreements among participants that some concepts (or sub-concepts) co-occurred in their responses. So, if two nodes are linked, it means the two corresponding concepts emerge together from within the content analysis, as referred to by the same person(s). Reversely, if two nodes are not connected, their concepts have not been mentioned together in any response by any participant.

- The resulting maps help us to explore the context of the participants’ words as well as their associations. Thus, the concept maps can be treated as network data, so methods of social network analysis (SNA) are applicable. For instance, once the networks were created per age and per question (also for all 36 participants), they were put in radial form to identify the central concepts that had the higher degree in the network and examine each node’s information centrality.

3. Results

3.1. Indicative Responses

Some indicative responses (exact quotations) per question, per age group follow.

- (i)

- Age group 20–30

Q1: How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences?

“Nostalgia… yes when I happen to go through the portals again; especially the ones that are not in my neighborhood I remember the phase and I like it. Exactly what I did before and after…As if it is my own creation and it is because I have given neutral buildings and neutral spaces a new personal meaning. Until now, the meaning these spaces had was either that I walked by them or went to work or that I went for a walk with friends. But now, they acquire an extra meaning for me”.

Q2: Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge?

“Undoubtedly yes, because it is like a game for elementary school, also for high school and even for high school (with a few modifications). As I teach at primary school, I am of the opinion that the geography lesson should be done outside, with the texts that appear, the maps in mountainous, lowland and coastal places, all over Greece. It would have a very positive effect on children to love geography…The answer is self-evident. Not only is it suitable for learning and teaching geography, it is also suitable because it is more lively and you participate so the lesson becomes more enjoyable if it’s done this way”.

- (ii)

- Age group 30–40

Q1: How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences?

“This is a very nice feeling; I feel like the sites I hacked belong to me now. They also express my beliefs, that is, they express my ideology because they are places that belong to my ideological group. Both groups express ideology. That is, they are also places of ideological conquest…Everything I told you before. Acquisition, conquest and possession of spaces something like property but without papers”.

Q2: Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge?

“Although, I do not think the game itself is suitable for teaching geography, what is offered here is the technology of augmented reality which opens new avenues in education. Elements of the game can be used in this direction, such as the map, but not the game itself”.

- (iii)

- Age group 40–50

Q1: How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences?

“The memory always has nostalgia. And when I go through the streets in which I played and hacked portals, I remember the whole phase, I recall it quite a bit…I felt an extra familiarity with the spaces I visited and had a feeling that Ingress players have a secret that others do not know. I also thought that the spaces around me could be something else that I do not know so far and so, I became more interested in history. That is, I want to know what was there in the past, how it was changed, what happened next, and why what happened”.

Q2: Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge?

“Technology, maps, texts are all offered and needed to be integrated into geography education. Certainly not the plot of the game! I think it is the modern way of teaching geography which (as usually happens) is not applied in today’s schools.”

- (iv)

- Age group 50–60

Q1: How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences?

“This game gives me the opportunity to feel something that was neutral is now mine. It is a sense of “ownership” of a building, a fountain, a feel of possession and intimacy together…I feel the space is mine, that I have enriched it with my thoughts, my feelings. I have left my mark and I can put myself in the shoes of the people who made what I see, whether they are just buildings or works of art”.

Q2: Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge?

“Not only does it offer opportunities, but in my opinion, geography needs to be taught today with games like Ingress, because our children like technology, whether we like it or not. They learn easier and most importantly thank them.

It could be used for geographical training (with some modifications of course). This made me think about the texts he displays with information. And it responds even better to today’s children who have grown up with technology. Education needs radical change and Ingress combines education with pleasure”.

3.2. Content Analysis

The content analysis of the responses to Q1 identified eight main concepts (Table 2) and six main concepts for Q2 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Table showing the concepts and sub-concepts of Q1.

Table 3.

Table showing the concepts and sub-concepts of Q2 (see text for explanation).

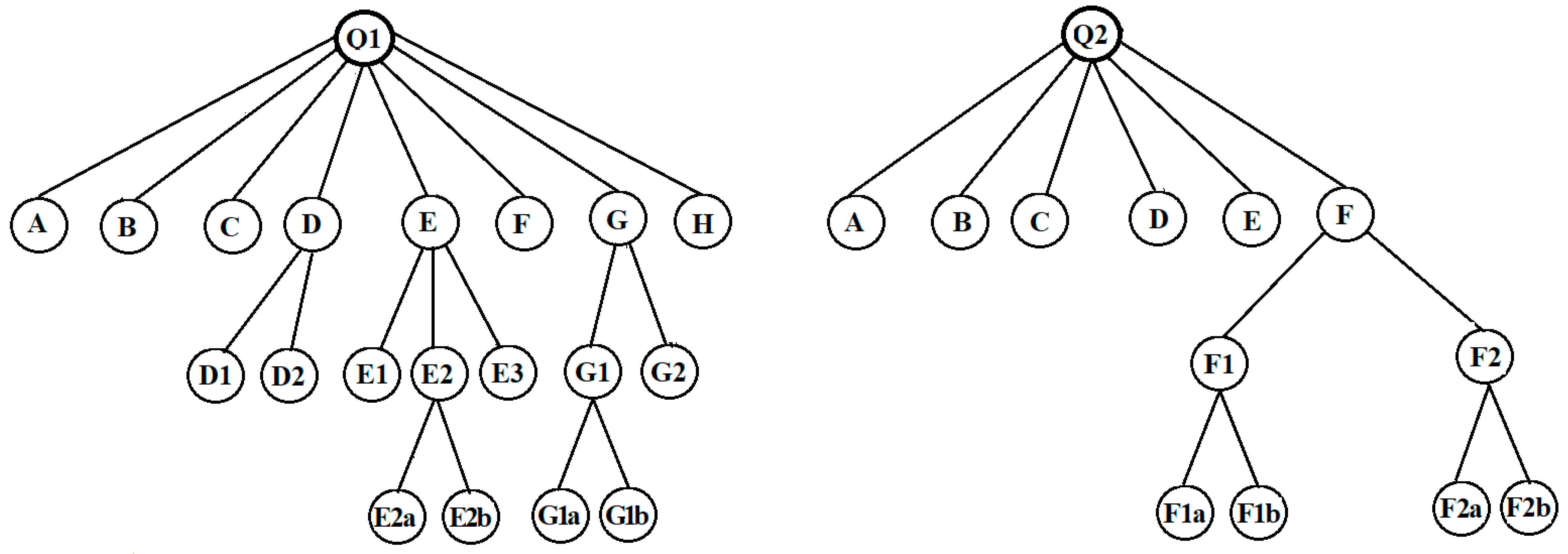

3.3. Concept Maps

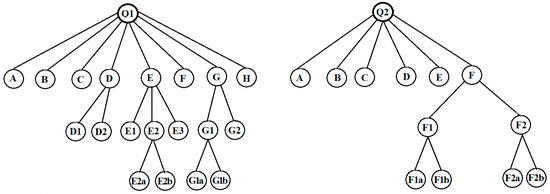

The concept and sub-concepts are articulated in tree-like structures (Figure 2). The structure of concepts of responses to Q1 is significantly more complex than those for Q2. From these tree-like concept maps, it is also possible to identify which concepts are more “critical” in each concept map: they are those that are modeled by a node that has the higher number of links. For question Q1, it is the concept E (the users feel a kind of nostalgia, which is specified by sub-concepts of E) followed by the concept G (the users consider portals as personal creations). In the case of question Q2, the most critical node is F (the participants believe that the game Ingress offers entirely new opportunities for education in geography, compared with their previous experiences).

Figure 2.

Concept maps (tree diagrams) showing the structure of the concepts and sub-concepts that have emerged from the content analysis of participants’ responses to questions Q1 and Q2.

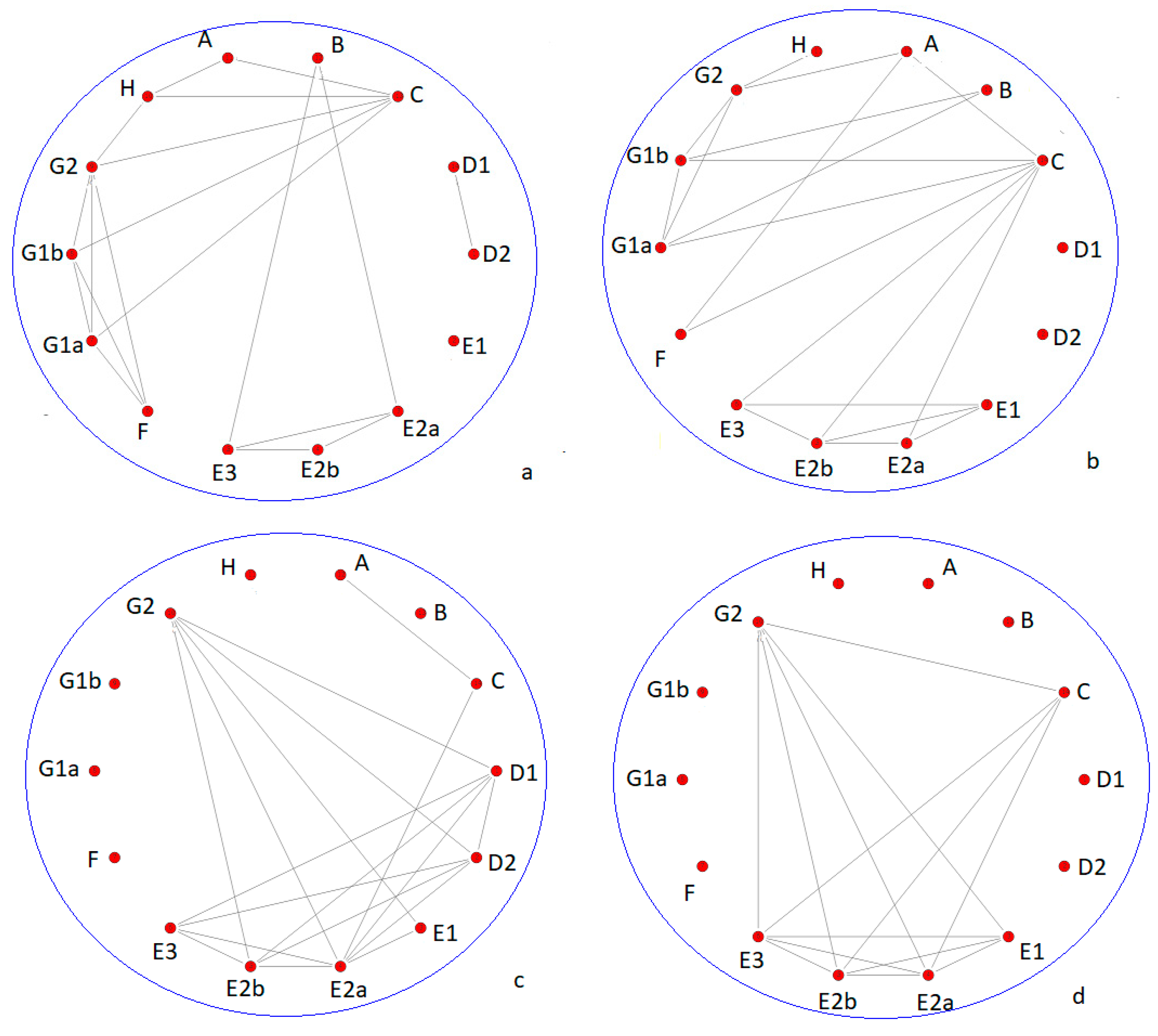

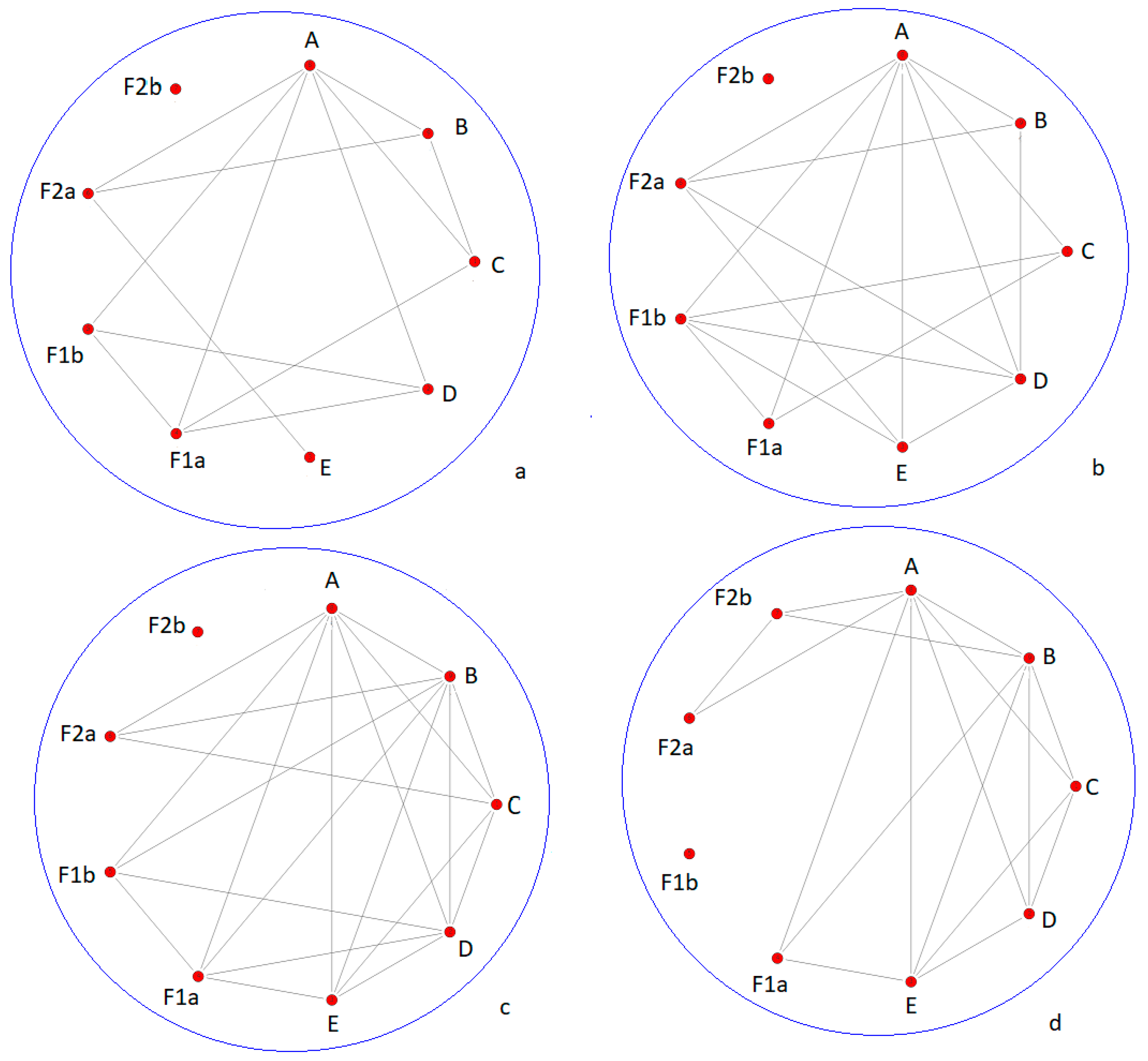

3.4. Network Representation of Concepts and Sub-Concepts

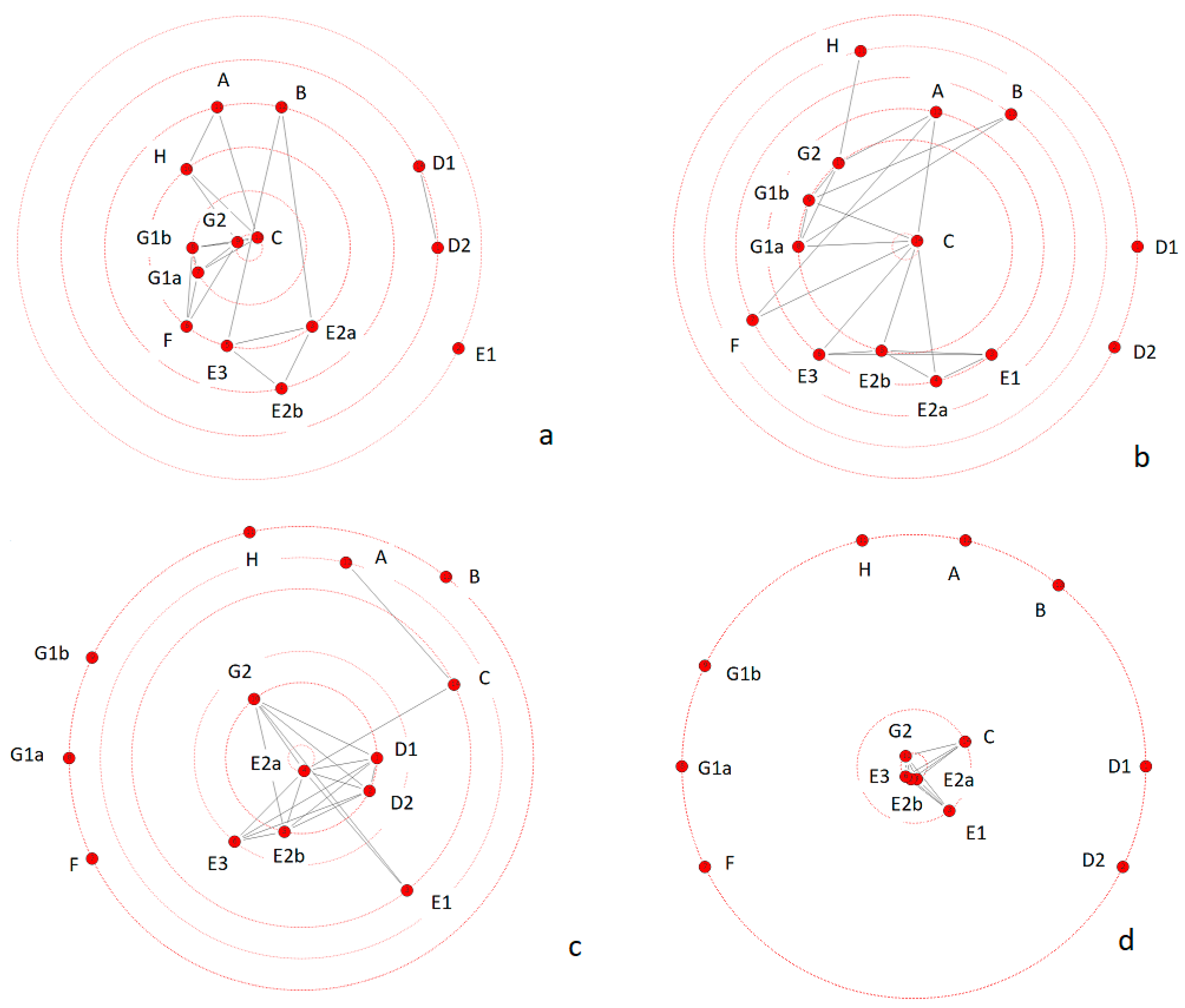

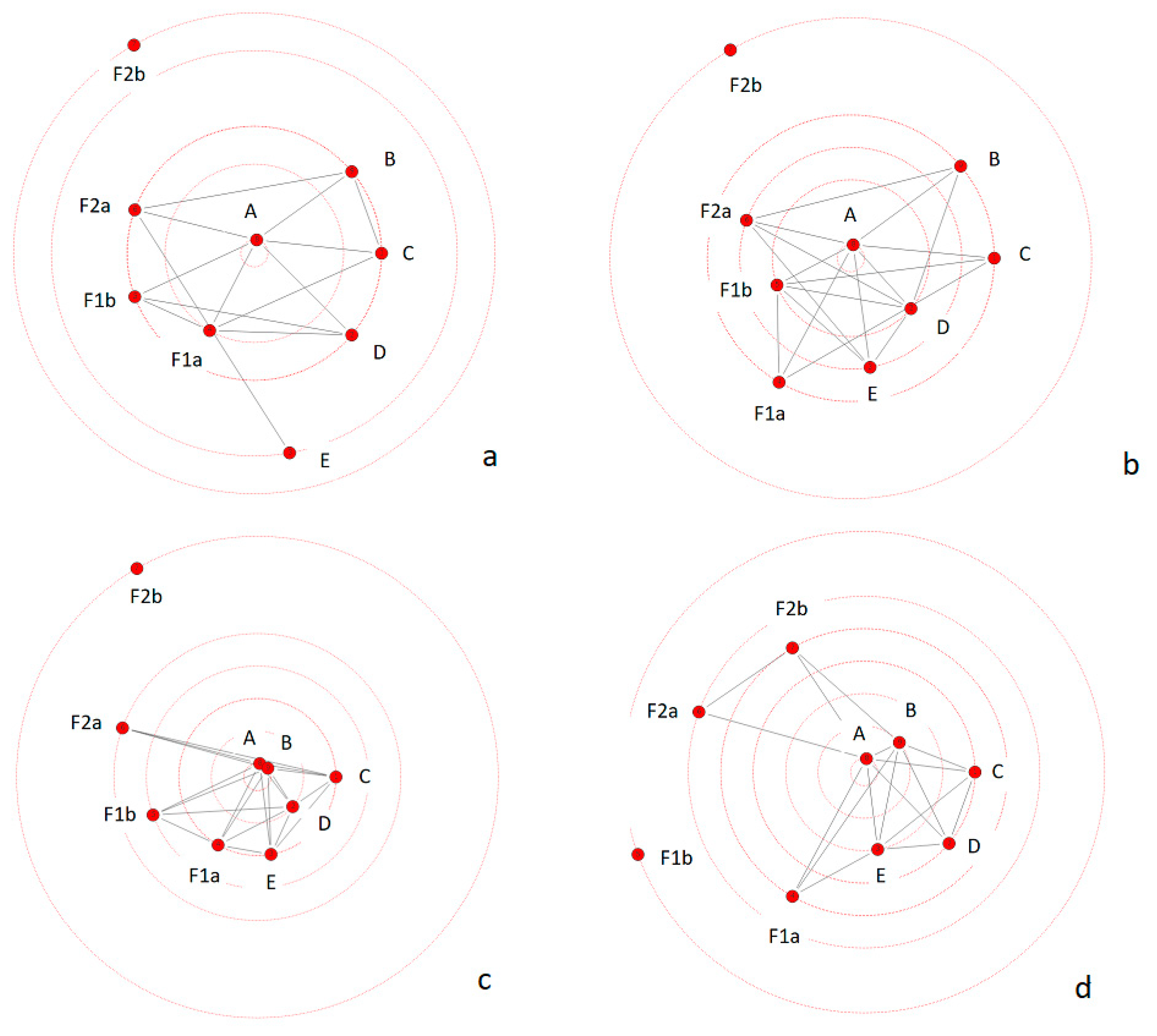

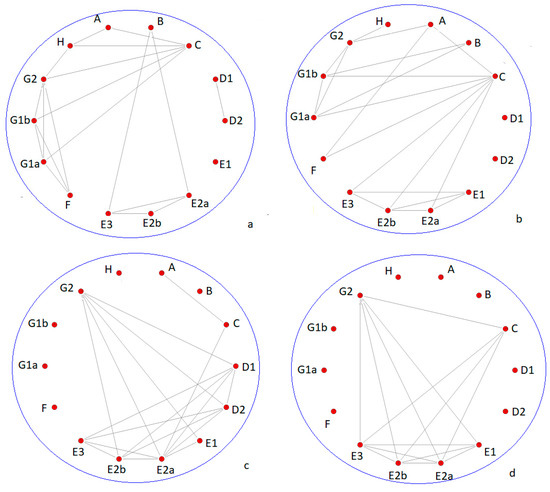

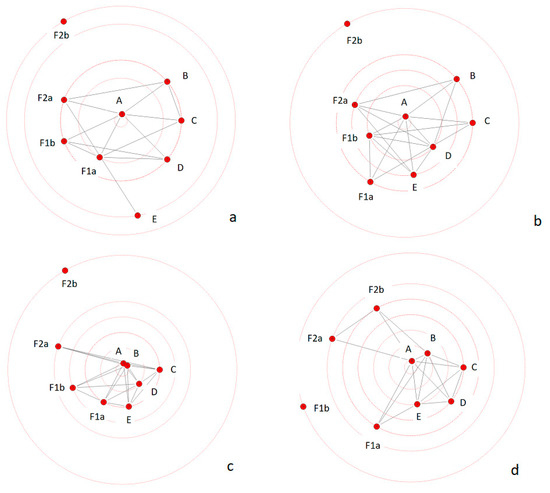

The agreements among participants for the concepts and sub-concepts of Q1 per age group (Figure 3) and Q2 (Figure 4) are presented in the form of networks, of which the nodes represent the concepts or sub-concepts and the edges (links) represent the agreements among participants (the occurrence of concepts).

Figure 3.

Network models of the co-occurrences of concepts and sub-concepts per age group: 20–30 (a), 30–40 (b), 40–50 (c), and 50–60 (d) for question Q1.

Figure 4.

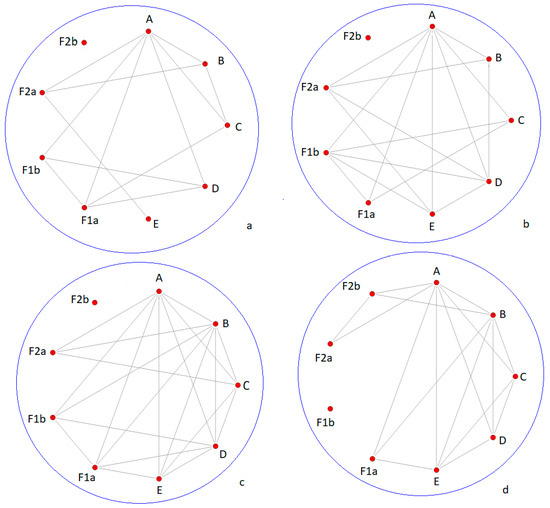

Network models of the co-occurrences of concepts and sub-concepts per age group: 20–30 (a), 30–40 (b), 40–50 (c), and 50–60 (d) for question Q2.

3.5. Network Analysis

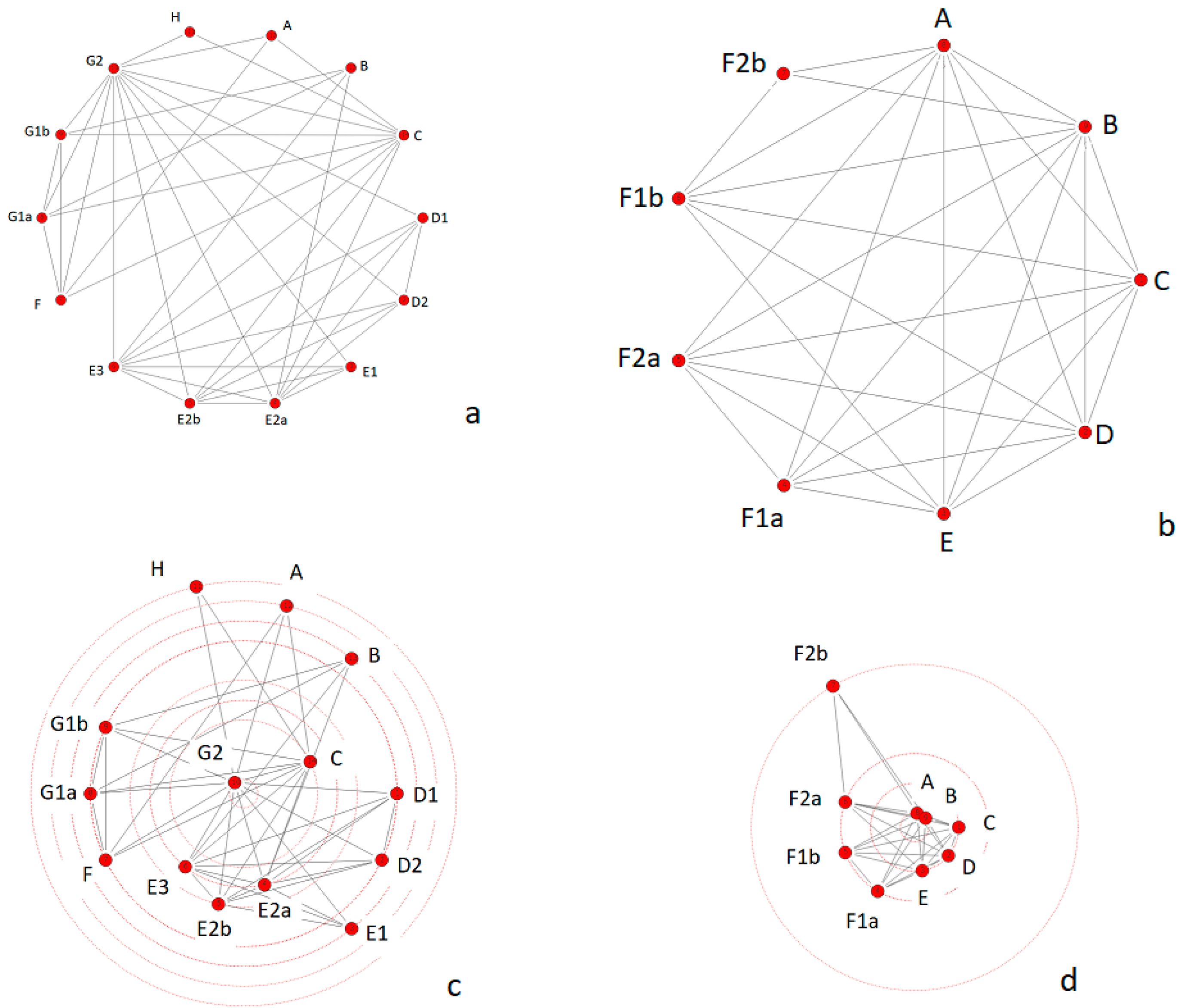

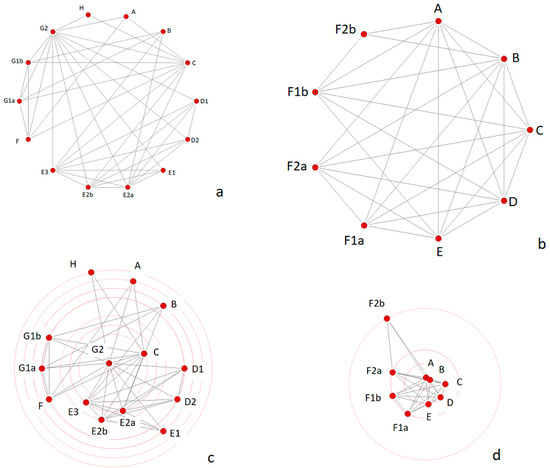

3.5.1. Node Centrality Analysis

A representation of the node degree of each concept (or sub-concept) in a way that highlights its centrality (per age group and per question) can also be created for Q1 (Figure 5) and for Q2 (Figure 6). These representations show the degree centrality of each concept or sub-concept in the network: the higher the degree of a concept, the more centrally located in the circle it is (and hence, the more inter-related it is with other concepts in the participants’ responses).

Figure 5.

Radial representation of the networks showing the node centrality of concepts and sub-concepts per age group: ages 20–30 (a), 30–40 (b), 40–50 (c), and 50–60 (d) for question Q1.

Figure 6.

Radial representation of the networks showing the node centrality of concepts and sub-concepts per age group: ages 20–30 (a), 30–40 (b), 40–50 (c), and 50–60 (d) for Q2.

Regarding the changes in a concept’s node centrality in Q1 as age progresses from 20 to 60, the following conclusions were drawn: personal footprint (C) → “personal footprint” (C) → “sights-texts” (E2a) → “route planning” (E3), “hack portals” (E2b), “sights-texts” (E2a). There are overlaps of preferred concepts/sub-concepts: in age groups 20–30 and 30–40 with “personal footprint” (C) as the central concept and another overlap in the age groups 40–50 and 50–60 with E2a (sights-texts) as the central concept.

For Q2, for the changing central concepts per age groupthe following conclusions were drawn: “augmented reality” (A) →“augmented reality” (A) →“augmented reality” (A), “texts” (B) →“augmented reality” (A), and so there was a persistent overlap of the participants’ responses among all age groups. For all age groups, the central concept in Q1 is “part of myself” (G2), and the central concepts in Q2 are “augmented reality” (A) and “texts” (B).

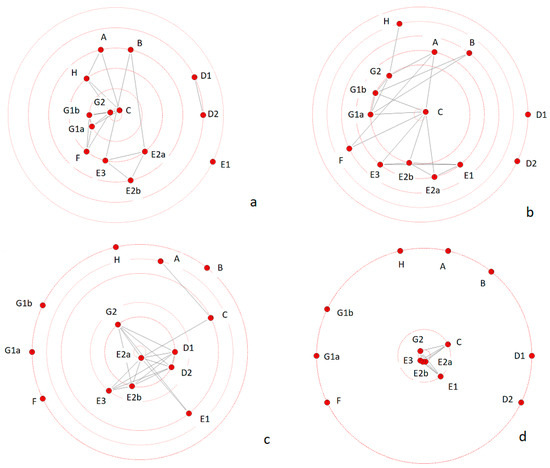

Yet, for all age groups (Figure 7), the concept G2 is central for Q1 while concepts A and B are more so for Q2.

Figure 7.

Agreements among concepts for Q1 (a) and Q2 (b) and radial representations of the respective networks showing the central concepts in each case ((c) for Q1 and (d) for Q2) for all participants (all age groups).

In fact, some common constructivist-based teaching and learning strategies that can be employed in constructivist-oriented learning environments emerge from these patterns. Playing Ingress involves problem-solving activities, provides visual formats and interesting mental models, provides rich learning environments, involves cooperative or collaborative group learning, and promotes learning through exploration. Constructivism emphasizes problem-solving and inquiry-based learning rather than instructional sequences for learning of certain content skills. Constructivist approaches to assessment generally assume that by actively engaging in each of the stages of the inquiry process, learners will construct a meaningful understanding of the research experience. Using Ingress is perhaps one of the best ways to achieve this advanced kind of learning and to observe the emerging new mental constructs, even with respect to age differences.

3.5.2. Information Centrality of Concepts

The information centrality index [28] measures the information flow through all paths between nodes (concepts and sub-concepts) weighted by strength of tie and distance. If there are i = 1, 2, 3, …, n nodes in the network, then the information centrality (Ii) of node i is calculated from the centrality of the node i with respect to all other nodes j and is defined by Stephenson and Zelen [28]:

The analysis of information centrality for all concepts and sub-concepts for both questions and per age group is shown in Table 4. It can be verified that the information centrality of the two questions coincides with their radial representation.

Table 4.

Highest values of the information centrality index for the concepts of questions Q1 and Q2.

4. Discussion

Our study showed how adult learners focus on different issues, which are ideally revealed through content analysis (“sub-concepts”) using networks. These findings support the theory that adult learners have a fully developed self-concept as a result of successful completion of a social task and can recall information from long-term memory [29]. From the participants’ responses to the questions, it is noticeable that Ingress highlights the fact that the game relates to constructivism. Adult students create their own subjective interpretations and meanings of what they have learned and they connect it to objective reality [30]. AR games offer excellent opportunities for working with physical materials and concepts to construct new knowledge. Taking images, recording movies, and/or sound, editing, and integrating perceptual information across various sensory modalities with the user’s environment in real time are examples of AR game-based constructivist activities. Previous studies [31,32,33] confirm that educational methods fostering constructivism, when appropriately used, can enhance the adult learners’ sense of belonging and can also foster their confidence and participation. According to Price [34], constructivism is a way of teaching adults that allows them to absorb information by building meaningful, concrete concepts and long-term understandings of reality through active experience and critical reflection. Brown et al. [35] stated that students should engage in problem solving within contexts that are familiar and valuable to them. Learning, according to the constructivism theory of “situated learning”, is not only the transmission of abstract and contextualized knowledge between individuals but also a social process that takes place within specified conditions such as activity, context, and culture [36]. The essential premise of “scaffolding” in learning, which is a distinguishing feature of this theory, is that tutors (or instructors) provide support as if they were creating a “scaffold” for the learners until they become able to assimilate the supplied new knowledge into their own cognitive frameworks. This could be the case with urban mobile games such as Ingress, in which the game play is affected by the sociocultural and material circumstances of the unique urban location in which it is played, but, at the same time, the game creates a new shared understanding of urban surroundings [37].

Content analysis and concept maps may be a better way to find out what they believe about the subject they are studying. Since each investigation is unique and the outcomes are determined by the investigator’s talents, insights, observational abilities, and style [38], content analysis is more complex than quantitative analysis [39]. One of the difficulties of content analysis is that it is very adaptable, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Researchers must figure out which combinations are best for their particular challenges [40], making the study process both challenging and exciting. In the literature on ICTs in education, this research method has received minimal attention. Backman and Kyngäs [41] regarded the beginning of the categorization process as chaotic, because researchers must deal with and classify many seemingly unconnected pieces of knowledge. Another problem is that the narrative content is rarely ever “linear”, and interview paragraphs can contain elements from numerous categories [39,42]. For this reason, network models were used.

However, there were certain limitations to our research. One is the small number of game players, and another is that some of the findings of this study may be skewed by specific geographical settings (i.e., different cities, cityscapes within the same city) or by the demographics of the participants, necessitating additional research under different conditions and with different participants. In addition, various findings may be obtained using alternate classifications of the four age groups, although this particular classification in four classes has revealed certain similarities and variations among age groups. Content analysis, on the other hand, is an excellent tool for analyzing such qualitative data, particularly those produced from adult education research [27].

Using concept maps in qualitative research presents several advantages for educational research. First, concept maps assist researchers to keep track of the meanings as they come out from within the interviews. When reading an interview transcript, it is easy to underestimate the depth of the concepts to which participants refer. The meanings associated to the concepts can be maintained thanks to the relationships represented by a concept map. Transcripts tend to represent spoken language in a linear format, whereas concept maps convey interview data in a hierarchical and interconnected manner. Graphical representations of concept maps are more akin to how we think and how we really communicate issues in an interview setting. In addition, concept maps assist us with minimizing data volume, illustrating links, and making (cross-group or other) comparisons easier. Possibly, the reader may find it difficult to distinguish which concepts are vital and which ones are secondary due to the intricacy of the interview that was carried out [43].

It is precisely for these reasons that the present research introduced the use of SNA, for first time, in two fields simultaneously: in education and in MAR games. From this application, SNA turned out to be a particularly useful and innovative approach to education for the following reasons:

- -

- The use of SNA to model concept maps opens up excellent opportunities to create visualizations of concepts and their inter-relationships.

- -

- Quantitative aspects of SNA analysis (i.e., by using radial centrality and information centrality) provide suitable mechanisms to measure internal relationships in concept maps (in addition to visual inspection) that would not otherwise be visible (or even perceptible) at all.

- -

- Using SNA enabled the classification of users’ responses with respect to their interaction with the game and therefore was a fruitful approach for education that involves MAR games

- -

- Furthermore, with this method, it is shown how texts derived from interviews or from responses to open questions by different individuals can be analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively with SNA.

While research findings relating to MAR games and videogames are only partially comparable, research in the latter type of games showed that younger adults up to 35 years old are more likely to enjoy such games [44,45]. However, the negativity of elder generations toward such games that has been identified in other research [46] may progressively disappear once they become more familiar with these games [47,48]. This lack of negativity in attitudes of elder adults (52+) was also observed in previous research with Ingress [49,50].

5. Conclusions

This study examined the responses of 36 adult learners in using the location-based MAR game Ingress to the two following questions: (i) How do you feel when you endow the geographical space with personal preferences? and (ii) Do you think that the game offers opportunities for learning and teaching geography, building on your previous geographical knowledge? The results were analyzed by means of content analysis, concept maps, and social network analysis.

It was revealed that adult learners utilized some common constructivist-based learning strategies, confirming that AR games touch upon various learning theories, with the paradigm of constructivism being one of the central ones. The use of the MAR game Ingress enhanced active and authentic learning and created the opportunity for exploring experiential learner-centered learning more than the typical educator-centered learning. Another interesting point is that AR games can be applied to any learning environment, either indoors or outdoors.

By applying content analysis and concept maps as techniques of qualitative research in order to measure the users’ responses to questions related to Ingress, it was found through central concepts that the space was part of themselves; by playing Ingress, they left their personal mark in the space, while the educational use of augmented reality was also emphasized. It was also found that there was a differentiation of the answers in question 1 between age groups with age groups agreeing in pairs, the first two (20–30) and (30–40) with the last two (40–50) and (50–60), while in question 2, there was an overlap in the responses of participants among age groups. In addition, methodologically, it is shown that content analysis and concept maps present the educational researcher with several advantages as they help to better visualize the links and subfields that emerge from interviews and participants’ responses. Furthermore, these responses can best be analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively by using methods of social network analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S., J.M.M.G. and M.D.H.-A.; methodology, K.S., J.M.M.G. and M.D.H.-A.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, K.S.; data curation, K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S.; visualization, K.S.; supervision J.M.M.G. and M.D.H.-A.; project administration, K.S., J.M.M.G. and M.D.H.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the fact that all participants were adults and participated by their own will.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, C.J.; Hsu, Y. Sustainable education using augmented reality in vocational certification courses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.K.; Lin, Y.H.; Wang, T.H.; Su, L.K.; Huang, Y.M. Effects of incorporating augmented reality into a board game for high school students’ learning motivation and acceptance in health education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spallazzo, D.; Mariani, I. Location-Based Mobile Games: Design Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schito, J.; Sailer, C.; Kiefer, P. Bridging the gap between location-based games and teaching. In AGILE 2015 Workshop on Geogames and Geoplay; ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Naismith, L.; Lonsdale, P.; Vavoula, G.N.; Sharples, M. Mobile Technologies and Learning. University of Leicester. Futurelab Literature Review Series, Report No 11. 2004. Available online: http://www.futurelab.org.uk/resources/publications-reports-articles/literature-reviews/Literature-Review203 (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Sharples, M.; Milrad, M.; Arnedillo-Sánchez, I.; Vavoula, G. Innovation in mobile learning: A European perspective. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. (IJMBL) 2009, 1, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Klopfer, E. Augmented Learning: Research and Design of Mobile Educational Games; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huizenga, J.; Admiraal, W.; Akkerman, S.; Ten Dam, G. Learning history by playing a mobile city game. In Proceedings of the 1st European Conference on Game-Based Learning (ECGBL), Paisley, UK, 25–26 October 2007; pp. 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Fun, play and games: What makes games engaging. Digit. Game-Based Learn. 2001, 5, 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.Y.; Chu, Y.L. Using ubiquitous games in an English listening and speaking course: Impact on learning outcomes and motivation. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouris, N.M.; Yiannoutsou, N. A review of mobile location-based games for learning across physical and virtual spaces. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 2012, 18, 2120–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Alnuaim, A.; Caleb-Solly, P.; Perry, C. Enhancing student learning of human-computer interaction using a contextual mobile application. In Proceedings of the 2016 SAI Computing Conference (SAI), London, UK, 13–15 July 2016; pp. 952–959. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, P.H.; Hwang, G.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Su, I.H. A cognitive component analysis approach for developing game-based spatial learning tools. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slussareff, M.; Boháčková, P. Students as game designers vs. ‘just’players: Comparison of two different approaches to location-based games implementation into school curricula. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2016, 29, 284–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, G.J.; Wu, P.H.; Chen, C.C.; Tu, N.T. Effects of an augmented reality-based educational game on students’ learning achievements and attitudes in real-world observations. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, D.M.; Oltman, J.; Vallera, F.L. Inside, outside, and off-site: Social constructivism in mobile games. In Handbook of Research on Mobile Technology, Constructivism, and Meaningful Learning; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barma, S.; Daniel, S.; Bacon, N.; Gingras, M.A.; Fortin, M. Observation and analysis of a classroom teaching and learning practice based on augmented reality and serious games on mobile platforms. Int. J. Serious Games 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutromanos, G.; Styliaras, G. “The buildings speak about our city”: A location based augmented reality game. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Kerkira, Greece, 6–8 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D. Learning, Creating and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D.; Gowin, D.B.; Bob, G.D. Learning How to Learn; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McLinden, D. Concept maps as network data: Analysis of a concept map using the methods of social network analysis. Eval. Program. Plann. 2013, 36, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.E.; Dickmann, E.; Newman-Gonchar, R.; Fagan, J.M. Using mixed-method design and network analysis to measure development of interagency collaboration. Am. J. Eval. 2009, 30, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W.R.; Sussex, W.; Korbak, C.; Hoadley, C. Investigating the potential of using social network analysis in educational evaluation. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. The Culture of Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K.; Zelen, M. Rethinking centrality: Methods and examples. Soc. Netw. 1989, 11, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enesco, H.E. RNA and memory: A re-evaluation of present data. Can. Psychiatr. Assoc. J. 1967, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weerasinghe, M.; Quigley, A.; Ducasse, J.; Pucihar, K.Č.; Kljun, M. Educational augmented reality games. In Augmented Reality Games II; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.M. Toward constructivism for adult learners in online learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2002, 33, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isha, A.; Rani, E.O. Comparative analysis of the discussion and constructivism methods of teaching adult learners in adult education. J. Educ. Pract. 2011, 2, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ference, P.R.; Vockell, E.L. Adult learning characteristics and effective software instruction. Educ. Technol. 1994, 34, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Price, A. Constructivism: Theory and Application. 2002. Available online: http//trackstar.Hprtec.Org/main/display.Php3Trackid=12128 (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Brown, J.S.; Collins, A.; Duguid, P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ. Res. 1989, 18, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Reder, L.M.; Simon, H.A. Situated learning and education. Educ. Res. 1996, 25, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K. A situated approach to urban play: The role of local knowledge in playing Ingress. In The Refereed Conference Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Digital Games Research Association of Australia; 2015; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/13296463/A_Situated_Approach_to_Urban_Play_The_Role_of_Local_Knowledge_in_Playing_Ingress (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Hoskins, C.N.; Mariano, C. Research in Nursing and Health: Understanding and Using Quantitative and Qualitative Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, K.; Kyngäs, H. Challenges of the grounded theory approach to a novice researcher. Hoitotiede 1998, 10, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User Friendly Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Daley, B.J. Using concept maps in qualitative research. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Concept Mapping, Pamplona, Spain, 14–17 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taddicken, M. The ‘privacy paradox’in the social web: The impact of privacy concerns, individual characteristics, and the perceived social relevance on different forms of self-disclosure. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Hiekkanen, K.; Hussain, Z.; Hamari, J.; Johri, A. How players across gender and age experience Pokémon Go? Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Przybylski, A.K. Electronic gaming and psychosocial adjustment. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e716–e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Donnellan, M.B. Are associations between “sexist” video games and decreased empathy toward women robust? A reanalysis of Gabbiadini et al. 2016. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 2446–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrigal-Pana, J.; Gómez-Figueroa, J.; Moncada-Jiménez, J. Adult perception toward videogames and physical activity using Pokémon Go. Games Health J. 2019, 8, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdravopoulou, K.; Muñoz Gonzalez, J.M.; Hidalgo-Ariza, M.D. Assessment of a location-based mobile augmented-reality game by adult users with the ARCS model. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdravopoulou, K.; Muñoz González, J.M.; Hidalgo-Ariza, M.D. Educating αdults with a location-based augmented reality game: A content analysis approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).