1. Introduction

Sports coaches play a key role in the athletes’ lives. In addition to specialized support, planning activities and organizing sports training, coaches are real mentors or role models for the athletes who they work with, providing inspiration, motivation and meaning. For this reason, coaches, as trainers of athletes who will perform at national, international, or Olympic level, should enjoy a balanced mental health and a high level of well-being.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought, among other negative changes, the need for online work in most areas of activity. In this context, coaches have an extremely difficult mission; firstly, they should learn how to use specific platforms and applications for online training; secondly, they should monitor the progress of the athletes they work with. Santi et al., analyzing 2272 Italian coaches, observed how the ability of coaches to reevaluate the situation created by the pandemic period helped them reduce their stress experience [

1].

For Romanian coaches, the transition to online training was a great challenge, especially among those accustomed exclusively to working on the sports field. Difficulties caused by lack of materials or poor access to online equipment, as well as job insecurity caused by diminished sports competitions can be factors of vulnerability for the coaches’ mental health. To overcome the emotional problems that occurred during isolation at home, coaches and athletes should pay a special attention by identifying and managing these conditions and seek for social support [

2].

1.1. Difficulties Related to the Material Basis

The current situation in Romania does not bring the premises of well-being among the coaches. Beyond the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which decreased the frequency of sports competitions, Romanian coaches also face countless other problems, such as the lack of materials needed to carry out the activity in optimal conditions, the lack of properly equipped sports fields, or modern training instruments for the evaluation and monitoring of athletes, obsolete technological equipment, and limited access to technology in general. All these lead to growth of personal efforts to compensate for the shortcomings generated by the lack of sport facilities.

At the individual level during this period, the coaches also feel a lack of security at their workplace, both in terms of quality (i.e., reduction of responsibilities by reducing the number of athletes and competitions, lack of financial investment in sports clubs) and quantitative (i.e., thoughts on actual job loss).

Given this reality, coaches may be prone to symptoms of depression, anxiety, or stress with harmful effects on their activity and involvement in professional activity.

1.2. Job Insecurity

In work psychology, job insecurity is perceived as a powerful harmful factor that can lead to emotional disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Job insecurity means the discrepancy between what the employee experiences and what he actually prefers, regarding the safety of his job [

3].

The concept of job insecurity has often been operationalized as a subjective phenomenon which largely depends on the work context and the way the employee perceives the work context. Job insecurity was defined as the perceived inability to maintain a desired continuity in a threatened job situation [

4]; other authors defined it as expectations regarding continuity in a job situation [

5]; or refer to this concept as the undesirable, subjectively perceived possibility of losing a job in the future [

6].

The quantitative-qualitative job insecurity dichotomy was introduced by Hellgren, Sverke and Isaksson [

7]. The quantitative dimension is defined as the fear of losing a job, while the qualitative dimension refers to the perception of diminished quality of job characteristics, with negative implications for the quality of life as a whole.

Job insecurity in the coaching profession is also common due to high job requirements, contracts that may end too soon, or unsatisfactory results, and disappointment of athletes or supporters. Although performance is an important feature in any field of activity, coaches run the risk of losing their jobs if they fail to bring athletes and the public the satisfaction they expect (win-loss records) [

8,

9]. A study conducted in Spain on a sample of 1481, coaches showed that their job insecurity reached higher levels than in other professions [

10].

Previous studies also highlight the negative effects that job insecurity has on the individual and the organization to which they belong [

11,

12,

13]. These effects include increased levels of anxiety [

14], burnout and depression [

13,

15], psychiatric problems [

16], a decrease in self-esteem [

17], and workplace performance [

18].

Studies on the relationship between job insecurity and the mental health of sports, coaches are not very numerous, but the period of the COVID-19 pandemic brings with it the need to investigate these issues among coaches, because they are the ones who motivate and support athletes’ performance in all areas. Without the sustained effort of coaches, athletes might not achieve their goals and Bentzen, Kentta, Richter and Lemyre conducted a longitudinal study involving 299 coaches. They found that job insecurity dramatically affects the well-being of coaches [

18]. In the same direction, Olusoga and colleagues conducted a qualitative study that revealed the negative effects of job insecurity on six elite coaches [

19]. Singh conducted a study involving 25 professional coaches from South Africa, showing that job insecurity is an extremely strong stressor [

20].

The conjunction between material difficulties and job insecurity accentuates the state of ill-being, putting coaches in a position to find solutions of compromise in the exercise of their profession. Thus, although their foreign colleagues use video applications and modern instruments to evaluate and monitor the evolution of athletes, most Romanian coaches still use the observation sheets or the simple stopwatch. In the context of a precarious material base and lack of access to technology, job insecurity can accentuate the intensity of ill-being. To maintain an optimal psychological balance, coaches can compensate for the lack of materials and instruments using their own experience and trying to adapt the old instruments to the new training requirements. If job insecurity is added to this effort, it is more likely that they will lose their energy resources and implicitly the enthusiasm to exercise their profession with major negative implications on their mental health.

Taking into account the above, we formulate the question whether the difficulties experienced by coaches in their professional activity and job insecurity could be predictors of the deterioration of their mental health. For this study, the following hypotheses were established:

Hypothesis 1. Material difficulties are positively associated with mental health issues (depression, anxiety, stress).

Hypothesis 2. Material difficulties are positively associated with job insecurity (qualitative and quantitative).

Hypothesis 3. Job insecurity (qualitative and quantitative) mediates the relationship between material difficulties and mental health (depression, anxiety, stress).

1.3. Work Meaning

The work of a coach has a direct impact not only on the physical and mental well-being of the athletes he trains, but also on the results obtained by athletes following participation in national, international, or Olympic competitions. Therefore, this type of work has not only an individual meaning, but much more general significance. The performances obtained by the athletes become emblematic for the whole society and represent the image in the world of the respective athlete or team. The meaning of work, in general, is a multidimensional construct that includes the meaning generated by work itself, but also the perception that work provides benefits for oneself and the environment [

21].

Meaningful work is seen as a way to bring harmony and balance into the lives of those who work, offering well-being, but also productivity, performance and dedication. Experts believe that people transcend their own immediate and self-centered concerns, orienting themselves towards others, which leads to experiencing a greater meaning in their lives [

22,

23]. The model developed by Steger and colleagues can be represented by three concentric circles that indicate the degree of people transcendence. In the central circle, there is the degree to which the person considers his work to be significant and meaningful. In the second circle, there is the degree to which work is in harmony with meaning and purpose in the person’s life. In the third circle, there is the degree to which work helps the person to contribute or to positively impact those around them or society as a whole.

Meaningful work occurs when people have jobs that require the use of skills, talents, and competences, having the ability to work so as to significantly impact the lives or work of their colleagues or others [

24].

Studies on work meaning have shown that it is positively associated with the well-being of employees, both hedonic (job satisfaction, life satisfaction) and eudemonic (life meaning, flourishing) [

25,

26]. People who consider their work to be significant report more frequent positive emotions [

27], more satisfaction with their lives [

28], and more meaning in life [

22]. At the same time, people who engage in meaningful work have lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress [

21].

Taking into account the above, we aim to verify whether the work meaning mediates the relationship between material difficulties and the mental health of coaches. We formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4. Work meaning mediates the relationship between material difficulties and mental health (depression, anxiety, stress).

3. Results

Data organization and statistical analysis for hypothesis testing were performed through SPSS 24 [

32] and Jamovi [

33]. The results were reported in mean values ± standard deviation. The normal distribution of the dependent variable was tested with the values for skewness and kurtosis which had acceptable limits (−3, 3) for skewness and (−10, 10) for kurtosis: −0.12 and −0.27 for material difficulties, 50 and −0.94 for qualitative job insecurity, 0.87 and 0.07 for quantitative job insecurity, −0.84 and 6.67 for work meaning, 2.07 and 6.62 for depression, 1.92 and 4.23 for anxiety, 1.27 and 1.68 for stress.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, Cronbach Alpha coefficients, and correlation coefficients among variables are presented in

Table 1 and means and standard deviations for specific difficulties in trainers’ activity are presented in

Table 2.

It was found that coaches showed higher levels of qualitative job insecurity (M = 9.38, SD = 5.02) than quantitative job insecurity (M = 7.29, SD = 3.49). At the same time, the level of work meaning showed relatively high (M = 45.57, SD = 4.82). For depression, anxiety and stress, the highest score was obtained for stress, M = 4.67, SD = 4.31, followed by anxiety, M = 3.19, SD = 3.93 and finally depression, M = 3.10, SD = 3.47. Skewness and kurtosis values showed adequate distributions, respectively (−0.12, 2.07) for skewness and (−0.94, 6.67) for kurtosis.

Regarding the difficulties faced by the coaches, they reported that they benefit from modern equipment for the evaluation and monitoring of athletes, and that they benefit from an adequate sport facilities, reporting results lower for the elements related to remote communication, so that for Internet access, M = 2.11, and for the difficulties encountered in providing information online, M = 2.54. Regarding the equipment used by coaches, 121 (61%) of them state that they do not use modern equipment in the training, evaluation and monitoring of athletes, and 79 (39%) use laptops, tablets, phone and video applications, observation sheets, laser, or stopwatch.

3.2. Hypotheses Testing

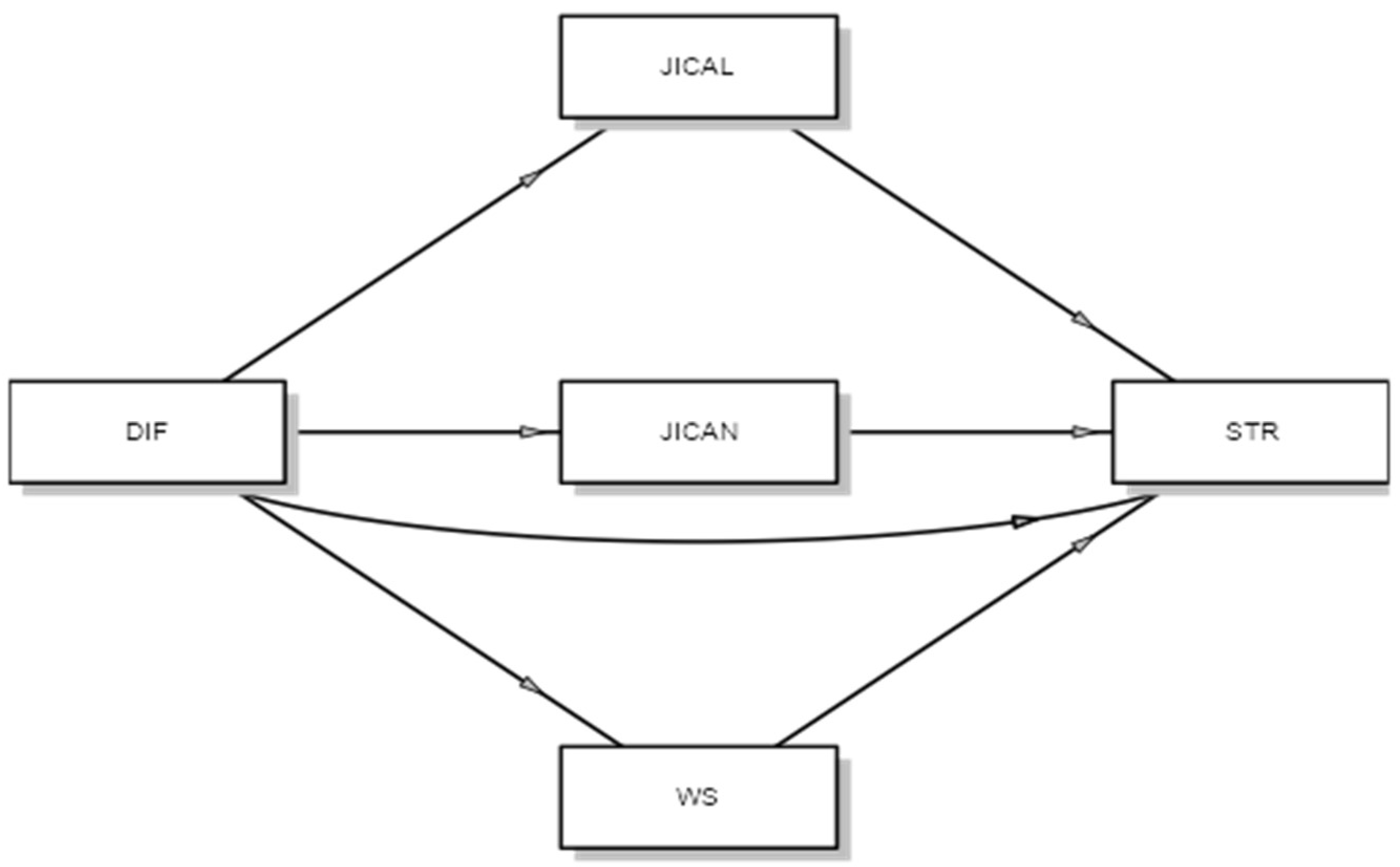

To test the hypotheses, three mediations were performed through medmod module of Jamovi (The Jamovi project, 2021) [

32]. Material difficulties were used as a predictor, qualitative and quantitative job insecurity were used as mediators, work meaning was also used as a mediator, and mental health, respectively depression, anxiety, stress were used as dependent variables.

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present the mediation diagrams.

Material difficulties were not directly associated with depression but were significantly and positively associated with qualitative job insecurity (β = 0.40, Z = 6.11,

p < 0.01) and quantitative job insecurity (β = 0.32, Z = 4.84,

p < 0.01). Qualitative job insecurity is positively associated with depression (β = 0.35, Z = 5.02,

p < 0.01), but quantitative job insecurity is not associated with depression. Work meaning is negatively associated with depression (β = −0.20, Z = −3.07,

p < 0.01. Qualitative job insecurity mediates the relationship between material difficulties and depression (β = 0.14, Z = 3.88,

p < 0.01). Neither quantitative job insecurity, nor work meaning mediates this relationship. The results are presented in

Table 3.

Material difficulties were not directly associated with anxiety, but were significantly and positively associated with qualitative and quantitative job insecurity, as we already reported in

Table 3. Qualitative job insecurity is positively associated with anxiety (β = 0.43, Z = 6.32,

p < 0.01), and quantitative job insecurity is weaker and negatively associated with anxiety (β = −0.14, Z = −2.08,

p < 0.05). Work meaning is negatively associated with anxiety (β = −0.18, Z = −2.90,

p < 0.01. Qualitative job insecurity mediates the relationship between material difficulties and anxiety (β = 0.17, Z = 4.39,

p < 0.01). Neither quantitative job insecurity, nor work meaning mediates this relationship. The results are presented in

Table 4.

Material difficulties were not directly associated with stress, but were significantly and positively associated with qualitative and quantitative job insecurity, as we already reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Qualitative job insecurity is positively associated with stress (β = 0.40, Z = 6.11,

p < 0.01), but quantitative job insecurity is not associated with stress. Work meaning is not associated with stress. Qualitative job insecurity mediates the relationship between material difficulties and stress (β = 0.14, Z = 3.89,

p < 0.01). Neither quantitative job insecurity, nor work meaning mediates this relationship. The results are presented in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

Descriptive statistical analysis shows that coaches have higher levels of qualitative job insecurity than quantitative job insecurity. These results reflect the coaches’ fear that their positions will change negatively, either by reduced number of athletes trained, or by participating in fewer competitions, or by the increased work demands caused by the conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The conditions for carrying out the activity are hampered by the lack of means of communication, access to the Internet, technical equipment necessary for the remotely evaluating and monitoring the athletes. At the same time, quantitative job insecurity shows the coaches’ fear that they will lose their job, which is less significant, but existing. The financiers of the sports clubs can order the dismissal of a coach if he does not obtain remarkable results with the athletes he trains, and the coaches are aware of this reality.

At the same time, the coaches consider that they have sufficient material resources to carry out their activity, mostly the scores obtained by them being above average. Their dissatisfaction with working conditions mainly refers to Internet access and online communication with the athletes they train.

Through the H1 hypothesis, we aimed to test whether material difficulties are associated with increased levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, but our results showed that there is no significant association between these variables. This result can be caused by the fact that coaches are accustomed to the material shortcomings, and they face them due to their level of experience that they have accumulated over time. They often use rudimentary methods for monitoring and evaluating athletes, but with satisfactory results.

Through the H2 hypothesis, we tested if material difficulties are associated with qualitative and quantitative job insecurity. The results showed that material difficulties have strong positive associations with both qualitative and quantitative job insecurity. This result can be caused by the fact that the material difficulties faced by coaches cause them to realize that their work with athletes suffers and therefore the performance they will achieve could be below the expectations of others (club owners, the public, the athletes themselves), which may endanger their job. From a qualitative point of view, they may be paid less or their rights may be withdrawn, and from a quantitative point of view, they may be replaced by other coaches at any time. Often, the lack of high performance from athletes, leads even to the abolition of the sports club.

Through the H3 hypothesis, we aimed to test if qualitative and quantitative job insecurity mediate the relationships between material difficulties and depression, anxiety, stress. Our results showed that only qualitative job insecurity mediates these relationships. It is possible that qualitative job insecurity mediates the relationship between material difficulties and depression, anxiety, stress through the pressure it puts on coaches. In the case of quantitative job insecurity, when they feel the danger of losing their job, it is possible to start a mobilization process, to move to another club or to search for another job, so the effects on their mental health are not so strong and negative. Instead, in the case of qualitative job insecurity, coaches continue to work hard, to hope that things will get better, to accept working conditions as they are. All this affects mental health and causes dysfunctional emotional states. In this situation, there is no question of giving up the job, but of continuing the efforts regardless of the conditions.

Through the H4 hypothesis, we aimed to test the mediating role of work meaning in the relationship between material difficulties and depression, anxiety, and stress. The results showed that work meaning associates negatively with depression and anxiety, but not with stress, and also that work meaning doesn’t mediate the relationship between material difficulties and depression, anxiety, and stress. The meaning of work is an activating mechanism that sets individuals in motion and gives them multiple possibilities to interpret reality. An unfortunate and oppressive reality in the context of work cannot be mediated by work meaning, but the emotional states determined by these contexts may be diminished when coaches consider that their work makes sense and can bring good results regardless of the conditions in which it takes place. At the same time, it is important to mention that the significance that coaches give to their work can counteract the depression and anxiety caused by the fear of losing their job or of work conditions changing. An individual who considers that his work is significant both for himself and for others (athletes, the public, club owners) will be less depressed or worried that he will lose his job. This is mainly due to his belief that being good at what he does will help him find a new job, in which he can highlight not only his professional qualities, but also the involvement in his work.

Although in the literature there are studies on the relationships between job insecurity, work meaning and mental health, there are relatively few studies that analyze these variables among coaches. However, our results are consistent with those of other researchers. A meta-analysis on the effects of job insecurity on mental health, showed that there is a close link between job insecurity and depression or the risk of depression [

34]. The same relationship was observed in the case of anxiety. A study on the factors that determine the level of well-being and mental health among coaches highlighted as risk factors competitive failures, high workload, sense of isolation, and as factors of effective protection organizational culture, transformational leadership, and perceived social support [

35]. Similar results were found in a study on job insecurity and the well-being of coaches [

18]. Thus, through a structural equation, the authors showed that experiencing a high level of job insecurity is associated with low levels of well-being, negatively impacting the professional and personal lives of coaches.

Work meaning doesn’t mediate the relationship between material difficulties and mental health but contributes to the mental health of coaches. Work meaning has in itself a series of components that contribute to maintaining well-being. The first is self-transcendence and refers to the fact that work is important not only for oneself, but also for those to whom it is addressed, in this case, not only for coaches, but also for the athletes they train and for the public that expect spectacular results from them which will make them feel proud. Another component of work meaning is that it can manifest itself in difficult moments, that only in the face of difficulties it can overcome and support the individual to counteract them, to overcome them, to go beyond them, maintaining at the same time acceptable mental health. Similar results to those obtained in this study showed that people who perceive their work as meaningful report a higher level of well-being [

36]. Work meaning has been shown to be an ameliorating variable of ill-being, helping to reduce the negative effects of working conditions on employees’ mental health, but also on turnover intentions in other studies [

37,

38].

Regarding the material difficulties that Romanian coaches face in their professional activity, they cannot be counteracted by giving a high significance to work. The coaches draw on their experience and try to use outdated equipment, with or without enthusiasm, but with the belief that this helps their athletes to achieve outstanding results in the competitions in which they participate.

5. Practical Implications

The novelty brought by this study consists in the introduction of professional (material) difficulties in coaching activity as an important factor that can have negative effects on coaches’ mental health. Material and technical difficulties will always be a challenge in the work of coaches and athletes. Moreover, job insecurity will reduce and work meaning will increase their well-being and mental health. Most of the time, the responsibility for the success or failure of athletes is placed on the shoulders of coaches, and this burden is felt both physically and mentally. An appropriate approach to this situation is to implement training programs for coaches to learn how to use online training platforms, how to evaluate and monitor athletes, how to enrich the facilities of sports clubs and how to attract funding for equipping sports fields with the necessary equipment. Coaches should also be given psychological support. Psychological support means those counseling approaches aimed at reducing the negative perception of the current context generated by the COVID-19 pandemic in sports and sports competitions, supporting coaches in maintaining the balance between professional and personal life, in adapting to current conditions, so different than the pre-pandemic conditions. Here are also included sessions for developing adaptive coping strategies, increasing resilience and frustration tolerance.

Regarding job insecurity, coaches should be trained through psycho-educational programs to carefully negotiate their rights and obligations within the sports clubs in which they work, as well as the general conditions of the workplace. Additionally, the increase of work meaning could be an essential objective of psychological counseling activities, through its development coaches can give special importance to their work, to see beyond the immediate results they achieve with the athletes they train, to understand that this is part of the general meaning of their lives.

Limitations and Further Research Directions

The results of this study must be interpreted in terms of certain limitations. The measurement of the difficulties encountered by the coaches was made with a set of seven items, specially formulated for this study. They may not capture enough of the totality and intensity of the various problems in the coaches’ professional life. In our future studies we will consider validated instruments for assessing these dimensions. At the same time, the differences between coaches who train athletes in individual and team sports were not highlighted, which might have brought interesting results. We will consider these differential aspects in our further studies. Regarding work meaning, we aim to investigate in the future how this psychological dimension of coaches impacts athletes, but also how work meaning is strengthened through the relationship between coaches and sports club managers.