Featured Application

Authors are encouraged to provide a concise description of the specific application or a potential application of the work. This section is not mandatory.

Abstract

The Madzaringwe Formation in the Vele colliery is one of the coal-bearing Late Palaeozoic units of the Karoo Supergroup, consisting of shale with thin coal seams and sandstones. Maceral group analysis was conducted on seven representative coal samples collected from three existing boreholes—OV125149, OV125156, and OV125160—in the Vele colliery to determine the coal rank and other intrinsic characteristics of the coal. The petrographic characterization revealed that vitrinite is the dominant maceral group in the coals, representing up to 81–92 vol.% (mmf) of the total sample. Collotellinite is the dominant vitrinite maceral, with a total count varying between 52.4 vol.% (mmf) and 74.9 vol.% (mmf), followed by corpogelinite, collodetrinite, tellinite, and pseudovitrinite with a count ranging between 0.8 and 19.4 vol.% (mmf), 1.5 and 17.5 vol.% (mmf), 0.8 and 6.5 vol.% (mmf) and 0.3 and 5.9 vol.% (mmf), respectively. The dominance of collotellinite gives a clear indication that the coals are derived from the parenchymatous and woody tissues of roots, stems, and leaves. The mean random vitrinite reflectance values range between 0.75% and 0.76%, placing the coals in the medium rank category (also known as the high volatile bituminous coal) based on the Coal Classification of the Economic Commission for Europe (UN-ECE) coal classification scheme. The inertinite content is low, ranging between 4 and 16 vol.% (mmf), and it is dominated by fusinite with count of about 1–7 vol.% (mmf). The high amount of inertinite, especially fusinite, with empty cells and semi-fusinite in the coals will pose a threat to coal mining because it aids the formation of dust.

1. Introduction

The Permian stratigraphy of the Tuli Coalfield from the base to the top comprises the Tshidzi Formation, Madzaringwe Formation, Mikambeni Formation, and Fripp Formation [1]. The Madzaringwe Formation in the Limpopo Province of South Africa is a coal-bearing late Paleozoic units of the Karoo Supergroup [2]. Coal is an important organic sedimentary rock because it is used or serves as a source of electricity generation in most countries, especially South Africa. Coal is formed or usually reproduces over millions of years [2]. In general, coal is formed under different degrees of temperature and pressure over long periods. A progressive increase in pressure and temperature will, among others, form different types of coal. Coal type is related to the type of plant material in the peat and the extent of its biochemical and chemical alteration. Coal petrology deals with the microscopic identification of the different components of coal and measurement of vitrinite reflectance to determine the coal rank or quality. Hence, coal petrology is a very vital tool in the classification of coal deposits as well as coal products [3].

The classification and characterization of coal for coke-making is significant because it allows for the selection of coals of a definite quality for specific coking operations and/or for estimating the quality of the coke that will be produced under certain conditions [3]. In the coke-making industry, “the strength of metallurgical coke is one of its most essential properties, and possibly one of the most vital uses of applied coal petrography is the ability to predict coke strength (ASTM stability) from single coals and coal blends” [4]. The coal rank and maceral constituent of coal affect the strength of the coke produced, and the ratio of reactive to inert macerals is of high importance when predicting the stability coke [5]. The reactive macerals are made up of vitrinite, liptinite, and semi-fusinite. The semi-fusinite is often used for South African coals to define a low-reflecting form of inertinite alleged to be reactive and which can increase or add to the reactivity of coal during carbonization [6]. The appraisal of South African coals for their coking characteristics entails a separate evaluation of the quantity of reactive semi-fusinite in the potential coal [7].

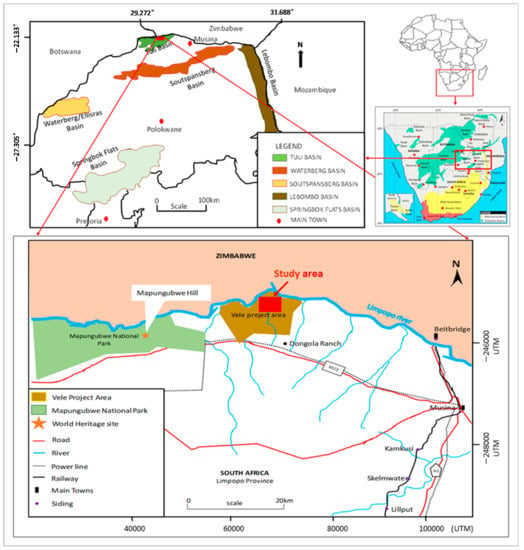

The Madzaringwe Formation, which is the focus of this study, has about 120 m coal-bearing unit and is the lowermost part of the Ecca Group in the Tuli Basin [5]. According to [8], the Madzaringwe Formation comprises three well-defined coal seams contained or hosted in a 150 m thick Main Coal Zone. These coal seams of the Madzaringwe Formation in the Vele Colliery are presently being mined. The Vele Colliery, which is the focus of this study, is geographically located between longitudes 29.56° E and 29.66° E and latitudes 22.15° S and 22.22° S (Figure 1 and Figure 2). About 10% of the Vele Colliery core yard is underlain by coal-bearing strata, containing a valuable proportion of coking coal in South Africa [9]. However, up to date, the organic petrological aspects of these coal seams have not been taken into consideration. In this study, an effort has been made to carry out an organic petrological study on some selected coal samples from the exploitable coal seams phase (mature and economic) in the Vele Colliery to assess coal quality, thermal maturity/rank, and other intrinsic characteristics of the coal.

Figure 1.

Map showing the Limpopo Karoo basins and location of the study area within the Vele Colliery (after [10,11]).

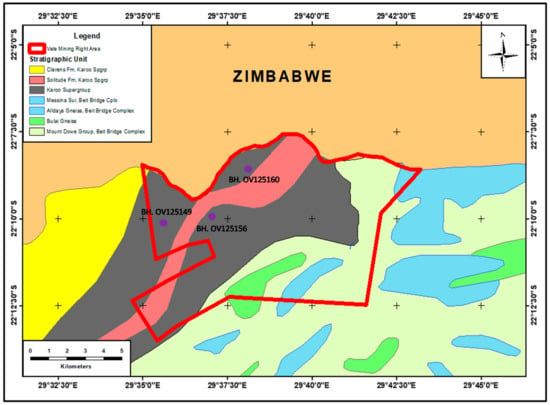

Figure 2.

Local geology of Vele Mining Right area (after [8]).

2. Geological Settings

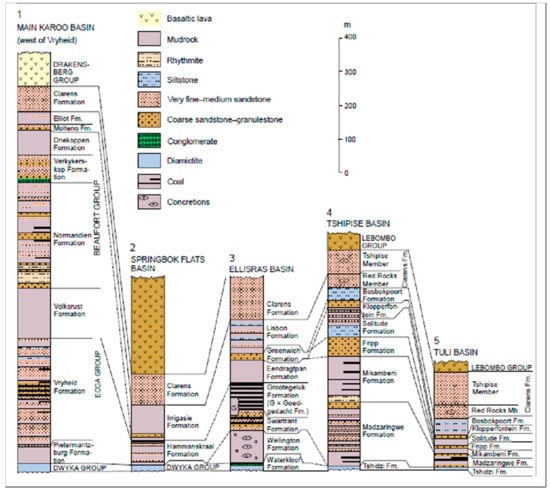

The Tuli Basin is thought to be a small intracratonic, east–west-trending fault-controlled basin with a preserved width of approximately 80 km [1]. The basin is present in the northernmost part of the Limpopo Province in South Africa, extending into Eastern Botswana and Southeastern Zimbabwe (Figure 1). These sediments of the Tuli Basin form part of the Limpopo Karoo Supergroup, and they were deposited contemporaneously with the main Karoo Basin sediments, forming an isolated and fault-controlled basin. The Tuli Basin was formed from approximately Late Carboniferous to Middle Jurassic in a continental tectonic setting [12]. According to [2], two broadly different tectonic settings were involved in the deposition of the Karoo Supergroup. The Tuli Basin forms the Limpopo part of Karoo-age basins. It has been proposed that the Limpopo area forms the western arm of a failed rift triple-junction [13], which later extended in a north–south direction and from the Save Basin in Zimbabwe to the Lebombo Formation in South Africa. Two distinct tectonic regimes that were sourced from the southern and northern margins of Gondwana led to the advancement of the Karoo Supergroup [14]. The authors of [15] reported that the Limpopo area, Karoo-age basins are made up of the following basins: Tuli Basin, Tshipise Basin (South Africa, partly Zimbabwe), and Nuanetsi Basin (Zimbabwe). According to the Tuli Basin, which trends approximately 1300 km east–west in the shared border region of South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Botswana, preserves an estimated thickness of 450–500 m of strata [2,12]. It has been interpreted as the down-dropped western arm of a failed triple junction related to the break-up of Gondwana [16,17]. However, an episode of Middle-Jurassic rifting and associated subsidence fails to accommodate the substantial record of pre-Jurassic strata preserved in the basin.

According to [18], the main Karoo Basin consists of four major groups, which are Dwyka Group (Late Carboniferous-Early Permian), Ecca Group (Permian), Beaufort Group (Late Permian–Triassic), and the Stormberg Group (Late Triassic–Early Jurassic). About 183 Ma, the Karoo sedimentary sequence was intruded by the Early Jurassic dolerites. The Tuli Basin consists of three formations, namely, the Madzaringwe Formation, Mikambeni Formation, and Fripp Formation. The aforementioned formations are the equivalents of the Ecca Group in the main Karoo Basin [2] (Figure 3). The sedimentary succession of the Tuli Coalfield consists of the Tshidzi Formation at the base and is mostly composed of diamictite and sandstones. The Tshidzi Formation is equivalent to the Dwyka Group in the main Karoo Basin. The Madzaringwe Formation forms the base of the Ecca Group and overlies the diamictites of the Tshidzi Formation [19]. It consists of sandstone, siltstone, and shale with thin coal seams with a maximum stratigraphic thickness of nearly 120 m [19].

Figure 3.

Stratigraphy and correlation of the main Karoo Basin and the northern sub-basins [21].

As documented by [20], the Madzaringwe Formation in Tuli Basin, which is the focus of this study, consists of an alternating succession of feldspathic, cross-bedded conglomerates, sandstone, siltstone, and shale comprising some coal seams [20]. Furthermore, they reported that this formation was deposited on top of the Tshidzi Formation. The coal series found in the Madzaringwe Formation are located at a depth of less than 50 m along the southern margin. The coal series can reach a depth of over 300 m close to the Limpopo River [2]. The two major seams which are represented as flat-lying coal have a thickness of about 1.6 m and 1.2 m [2]. These seams are overlain by mudstones and minor sandstones. The economically important coal succession in Madzaringwe Formation is interbedded with mudstones [12]. Succeeding the Madzaringwe Formation is the Mikambeni Formation, which is about 60 m thick, consisting of shale, sandstone, and coal. The Flipp Formation overlies the Mikambeni Formation and is composed of about 5–10 m thick successions of sandstones and conglomerates [2]. The Fripp Formation is overlain by the Solitude Formation, which is the equivalent of the Beaufort Group in the main Karoo Basin [12].

3. Materials and Methods

Three coal seam horizons occur in the Madzaringwe Formation within the Vele colliery. These seams are termed bottom seams, middle seams, and top seams based on the Coal Africa nomenclature [8]. It is important to highlight that only the middle coal seam is mined or of economic interest due to its coalification degree. Hence, the middle coal seam was further differentiated into upper middle, middle middle, and bottom middle coal seams for mine identification. The three existing boreholes of OV125149, OV125156, and OV125160 intersected the middle coal seams. Three samples were collected from borehole OV125156 and two samples each were collected from boreholes OV125146 and OV125160, and these samples were labeled as per mine identification (Table 1). A total of seven representative coal samples were collected from the Madzaringwe Formation for maceral group analysis. The sample selection was based on the lithological changes. The maceral group analysis was carried out at the Coal Petrography Laboratory, University of Johannesburg. Sample lumps, approximately 15 mm × 20 mm in size, were cut and placed in 30 mm cups, set in epoxy resin, and placed under vacuum for 24 h. The hardened block was polished as per the ISO 7404 (part 2) [22] guidelines, with a final stage polish using a 0.05 µm OPS lubricant with a Struers Tegraforce polisher. The polished sample (Table 1) blocks were analyzed using a Zeiss AxioImager reflected light petrographic microscope fitted with a Hilgers Diskus-Fossil system for vitrinite reflectance determination (ISO 7404, part 5) [22]. A detailed macerals analysis (in accordance with ISO 7404 (part4)) [22] was conducted at a magnification of ×500 under oil immersion. To precisely determine the coaly matter, the samples were viewed under white light (monochromatic and color cameras), fluorescent mode (to determine the degree of fluorescence), and under crossed polars (to determine the degree of anisotropy). Each sample was photographed at ×100 (air lens) and ×500 (oil immersion lens). The maceral analysis was calculated in terms of total reactive (vitrinite + exinite + semi-fusinite) and total inerts ( semi fusinite + other inertinite macerals + mineral matter) [23]. The organic fragments in coal were classified into three groups (vitrinite, inertinite, and liptinite maceral groups) based on their petrographic characteristics [21,23]. Each of the group is further subdivided into macerals and sub-macerals. The coal petrographic results are reported on a % volume basis, including and excluding mineral matter (mmf) for macerals analysis and micrographs. Thereafter, the vitrinite reflectance analysis results were plotted on the Coal Classification of the Economic Commission for Europe (UN-ECE) coal classification scheme to classify it in terms of coal rank.

Table 1.

Description of the coal samples analyzed for the maceral group.

4. Results

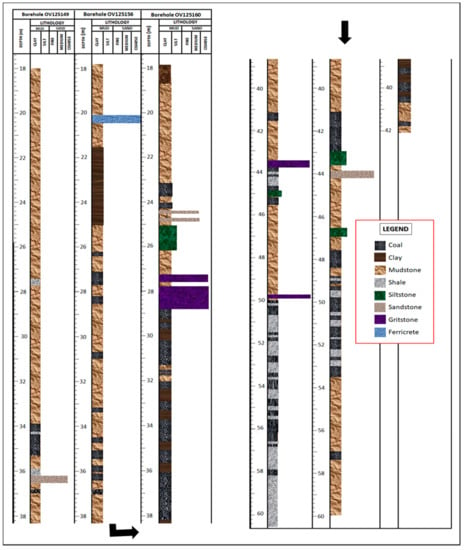

The stratigraphic sequence of the Madzaringwe Formation in the Vele colliery consists mostly of mudstone and carbonaceous shale with thin layers of coal seams, siltstone, and sandstones (medium and coarse-grained sandstones). The Madzaringwe Formation has a thickness of about 61 m, 60 m, and 42 m in boreholes OV125149, OV125156, and OV125160, respectively (Figure 4). The black coal is commonly interlayered with shaly coal (immature coal). The color of coal is black with a type of vitrinite coal that varies from dull heavy coal, bright coal, and combination of bright and heavy coal, with the occurrence of pyrite and sometimes calcite nodules. Samples TM-1, TM-2, and TM-3 are dull and heavy vitrinite coal, whereas samples MM-1, MM-2, BM-1, and BM-2 are bright coal with a combination of both bright and dull color. The result of the maceral group is presented in Table 2. The petrographic characterization revealed that vitrinite is the dominant maceral group in the coals, representing up to 81–92 mmf vol.% of the total sample. Collotellinite is the dominant vitrinite maceral, followed by corpogelinite, pseudovitrinite, and tellinite (Table 2). The inertinite content is very low in the studied samples, ranging from 4 to 16 mmf vol.%, and it is dominated by fusinite. Liptinite ranges from extremely low in the top samples (0.5 mmf vol.% in sample TM-1) to high in the bottom sample (12 mmf vol.% in sample BM-2). The sedimentary rock partings within the coal seams show some induration or alteration along with minerals such as iron oxides, calcite veins, calcium carbonates, siderite, and pyrite nodules. Some of the coal seams and partings are highly fractured, and they sometimes exhibit slickensides.

Figure 4.

Stratigraphy of the Madzaringwe Formation in boreholes OV125149, OV125156, and OV125160. Note: No core recovery from the surface down to a depth of 18 m.

Table 2.

Result of the maceral group analysis.

5. Interpretation and Discussion

5.1. Maceral Group

5.1.1. Vitrinite

The vitrinite maceral group is with a reflectance generally between the range of the darker liptinites and lighter inertinites. The vitrinite group consists of three subgroups and six macerals. These macerals are derived from different humic materials with varying pathways of transformation within the peats. The different types of maceral groups, as well as their origin, are presented in Table 3. Molecular components of plants do not produce macerals and maceral groups but constitute lithotypes, which later formed the coal. For instance, vitrinite, with or without small amounts of liptinite and inertinites, consists of vitrain, durain, and clarain. The durain is made up of three maceral groups in approximately equal proportions. The fusain dominates the inertinite group, whereas the clarain is a blend of vitrain and durain [23].

Table 3.

Maceral groups and their origin [23].

Collotellinite is the dominant vitrinite maceral with 38.5 to 57.7 inc. mm vol.% in the samples. The dominance of collotellinite gives a clear indication that the coal in the Vele colliery is derived from the parenchymatous and woody tissues of roots, stems, and leaves, composed of cellulose and lignin, and originating from herbaceous and arborescent plants [23]. By geochemical gelification (vitrinitization), the primary structures disappear. The precursor of collotellinite in low-rank coals is ulminite. At higher rank levels, collotelinite is also formed from telinite and its vitrinitic cell fillings. According to the vitrinite classification scheme [24], collotelinite is very common in shaly coals, and it is kerogen Type III.

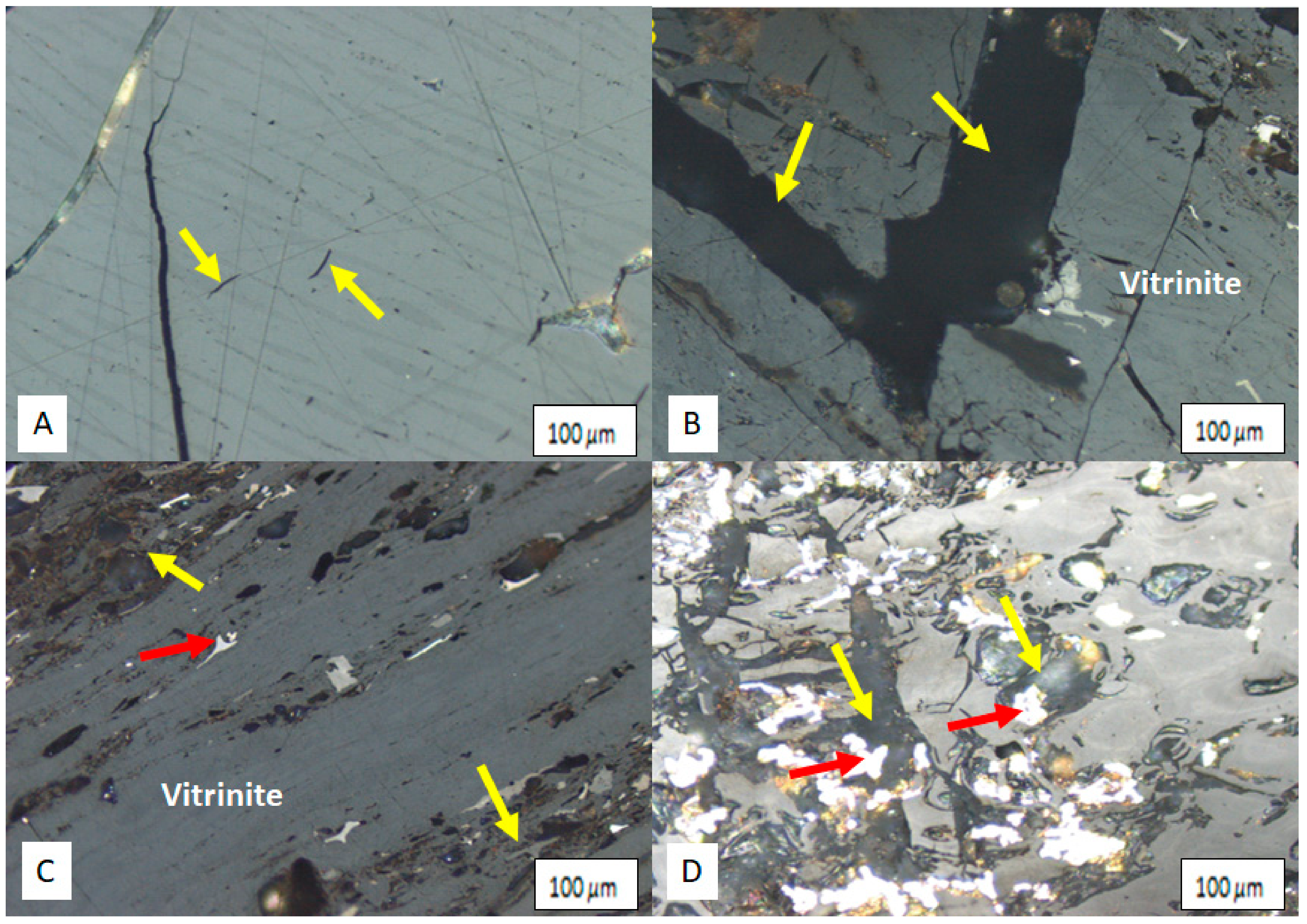

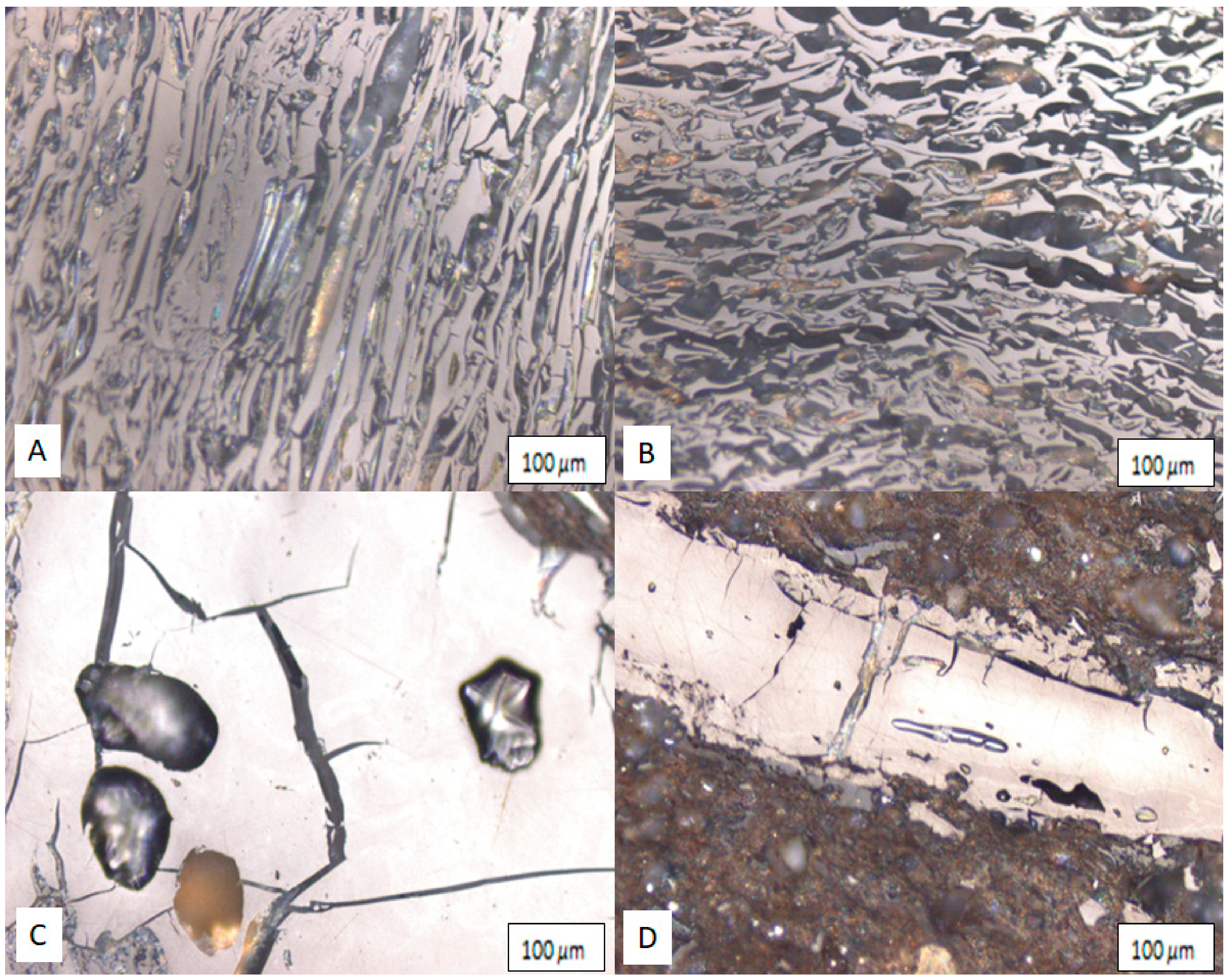

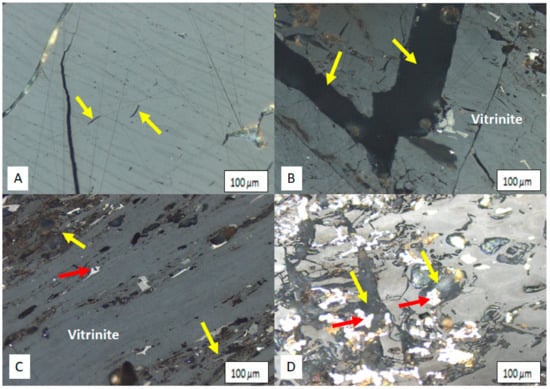

In the analyzed samples, collodetrinite ranges from 1.2 to 8.9 mmf vol.%. According to the vitrinite classification [24], it is derived from parenchymatous and woody tissues of roots, stems, and leaves, composed of cellulose and lignin. The original plant tissues are crushed by strong decomposition at the beginning of the peat stage. The small particles are cemented by humic colloids within the peat and successively homogenized by geochemical gelification (vitrinitization). Cellulose-derived substances may be the main source of collodetrinite rather than lignin-rich wood precursors of collodetrinite in low-rank coals such as attrinite and densinite [25]. The corpogellinite in the samples ranges from 1.0 to 19.4 maceral mmf vol.%. Corpogellinite belongs to the gelovitrinite subgroup within the vitrinite maceral group and is made up of homogeneous and discrete bodies, signifying cell infillings. Corpogelinite may be of a primary source corresponding to cell contents, derived from the tannin in part; it may also have been derived from secretions of the cell walls. Instead, it may contain secondary infillings of tissue cavities by humic solutions, which consequently precipitates as gels during peatification and early stages of coalification. All the analyzed samples tend to have pseudovitriite (Figure 5 and Figure 6), which according to [26] is a sub-maceral of vitrinite [27]. Pseudovitriite is considered to be an alteration product of collotelinite derived by devolatilization and desiccation or oxidation or combination of the processes [23]. Therefore, it is clear that pseudovitriite is known to affect the swelling properties of the coals despite the very high vitrinite content [2]. The observed vitrinite in coals is formed as an outcome of anaerobic preservation of lingo-cellulosic material in swamps. It also occurs in the shaly coal where organic and mineral matter were deposited rapidly. Vitrinite is the main component of bright coal encompassing the microlithotypes vitrinite, vitrinertite, and clarite.

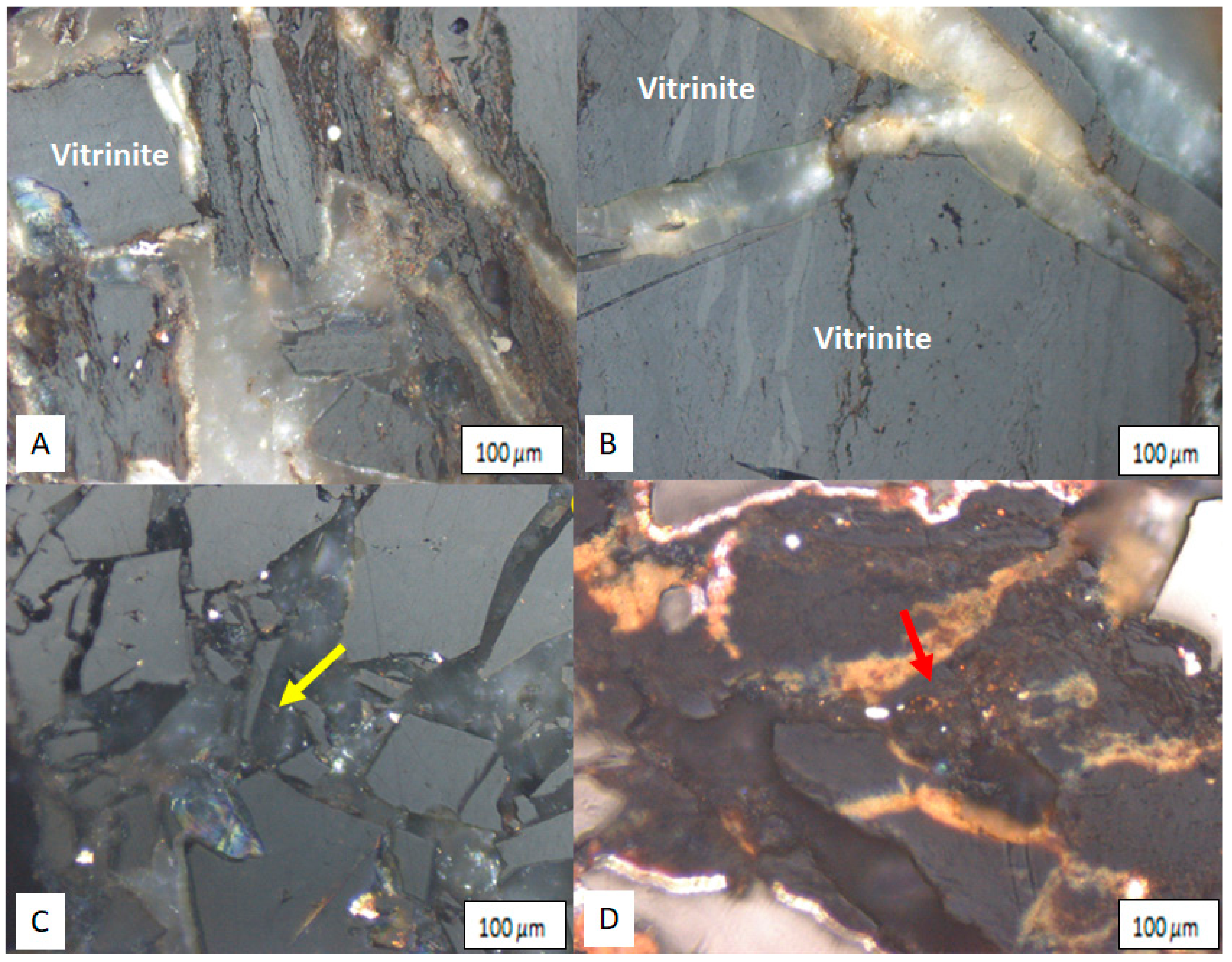

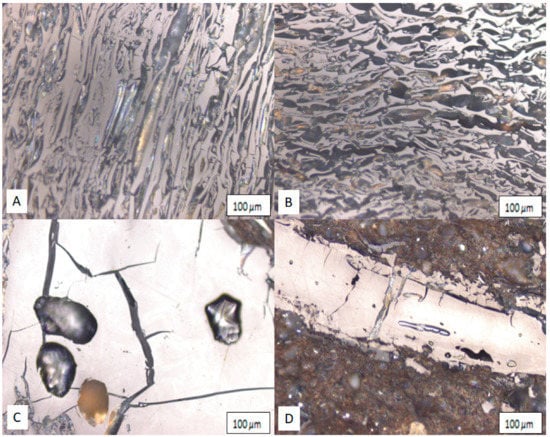

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of coal showing: (A) pseudovitriite; (B) vitrinite and sporinite (yellow arrows); (C) vitrinite, clay minerals (yellow arrows), and inertodetrinite (red arrow); and (D) quartz (red arrows) fillings in vitrinite (yellow arrows).

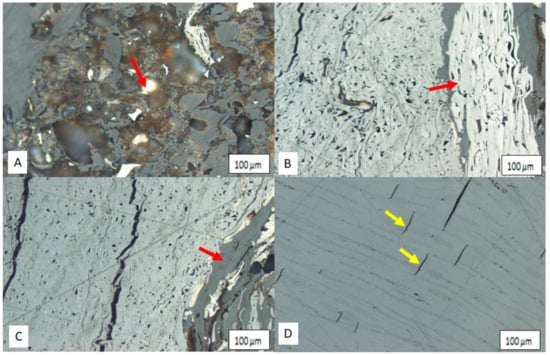

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of coal showing: (A) vitrinite with clay and carbonates (red arrow); (B) fusinite and semi-fusinite (red arrow) with small layers of vitrinite; (C) semi-fusinite with dark grey vitrinite (red arrow) and cracks called pseudovitriite; and (D) pseudovitriite (yellow arrows) in light grey collotellinite.

5.1.2. Inertinite

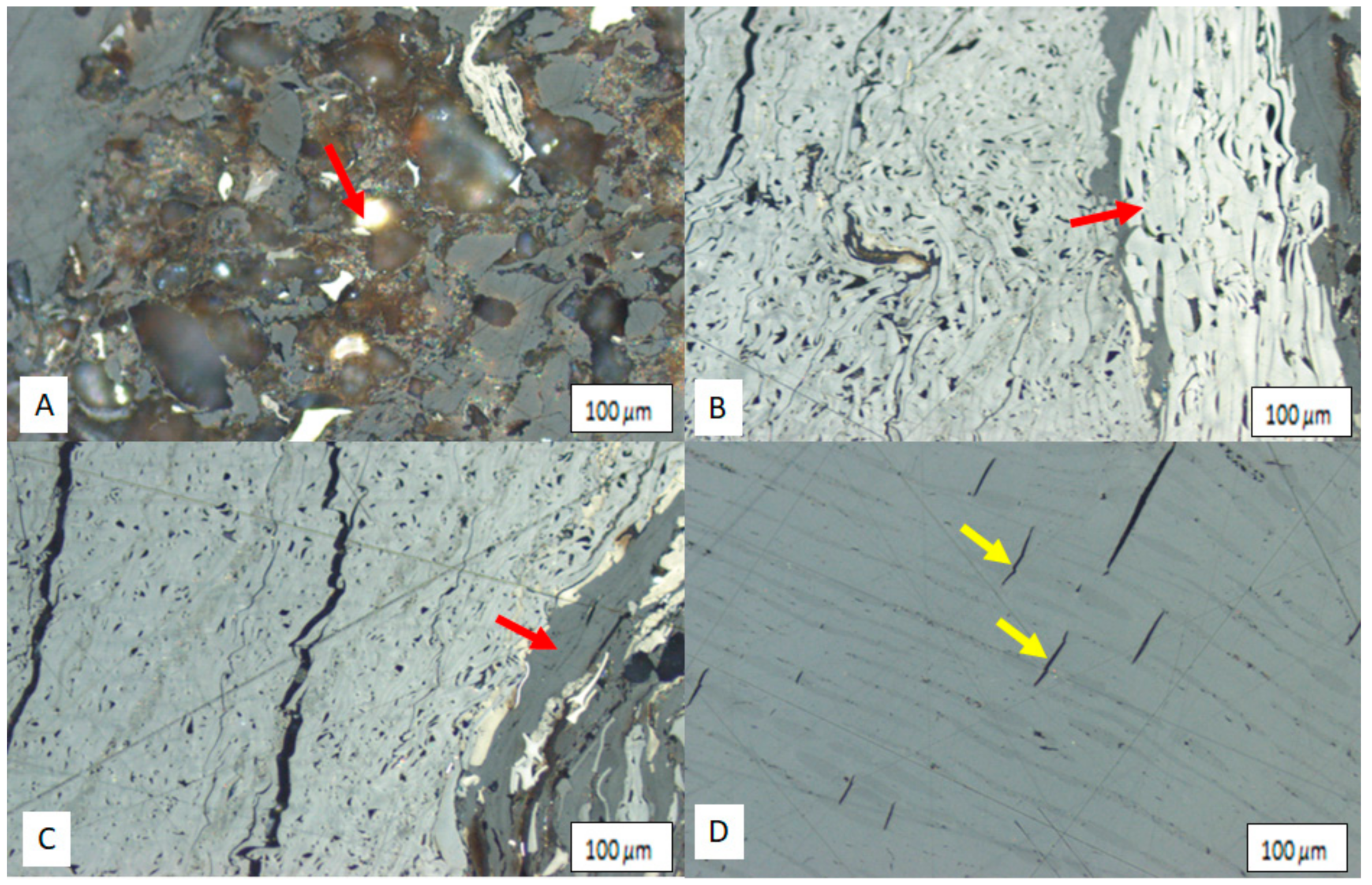

The Inertinite content is very low in the studied samples, ranging from 4 to 16 mmf vol.%, and it is dominated by fusinite and semi-fusinite (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The higher amount of inertinite, particularly fusinite with empty cells and semi-fusinite (Figure 7) in coals, supports the formation of dust during mining. It is also believed that the partly fusible and infusible inertinite acts as learning material in coal blends, but it improves the coke strength when dispersed. In the analyzed samples, the middle coal seam appears to have a lesser amount of inertinite. Fusinite is believed to occur in discrete lenses, thin partings of bands, and it may be transported by water or air into the mire sedimentary basin, but it may also have originated from in situ burning. Fusinite is a characteristic composition identified as kerogen IV (dead carbon).

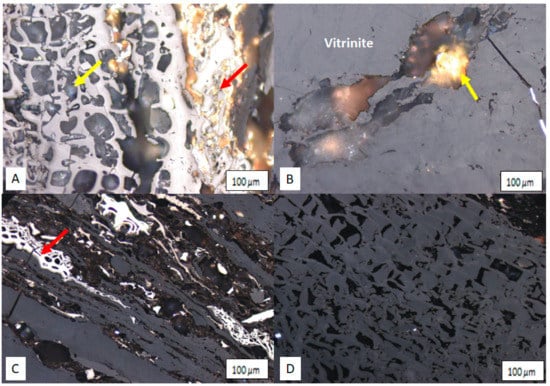

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of coal showing: (A) fusinite with pyrite inclusions; (B) semi-fusinite with pyrite inclusions; (C) pseudovitriite with detrital vitrinite particles; and (D) fusinite maceral surrounded by clay minerals.

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph of coal showing: (A) semi-fusinite (yellow arrow) with pyrite (red arrow); (B) vitrinite maceral with pyrite minerals; (C) fusinite (yellow arrow); and (D) semi-fusinite maceral.

5.1.3. Liptinite

Liptinite ranges from extremely low in the top samples (0.5 mmf vol.% in sample 1675) to relatively high in the bottom sample (12 mmf vol.% in sample TM-1). Sample number TM-1 is dominated by cutinite. Cutinite comprises fossil cuticles which form protective layers of cromophyte epidermal cells. Cuticles arise from leaves and stems. Moreover, endodermal matter and ovular embryo sacs are present in the initial materials of cutinite. Nonetheless, most cuticle fragments are derived from leaves because these are produced and shed in great number [28]. Cuticle analysis in combination with spore analysis may aid the correlation of coal seams [29]. Additionally, it plays a significant role in the assessment of facies and stratigraphic questions and the reconstruction of plant communities of brown-coal paleo mires [30]. The occurrence of cutinite in contrast to the very low proportion of liptinite in the top samples indicates different depositional and preservation environments through the sequence.

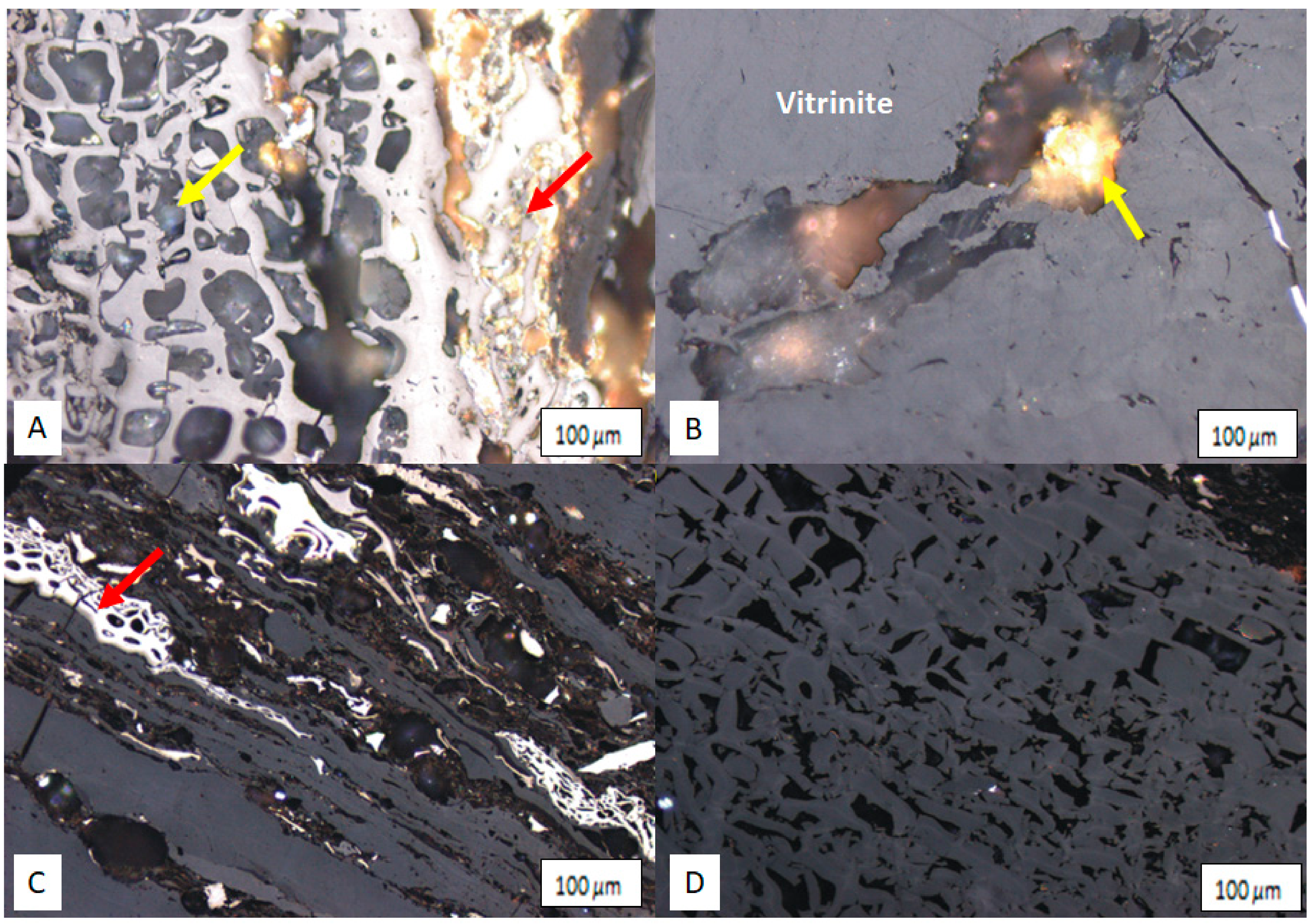

5.2. Mineral Matter in the Coal

Common minerals in the coal samples are calcium-iron minerals such as calcite, ankerite, and siderite and pyrite, and also silica in the form of quartz and silicate of clay minerals. The latter minerals are frequently derived from groundwater passing through cracks and fissures in the hardening or hardened coal seams. When saturated, the ions and elements in the groundwater precipitate out, resulting in the formation of mineral, which often takes the shape of the cracks or fissures in which they are precipitated/deposited. The minerals could have formed by water passing through the xylem phloem or cortical cells (supportive and “feeding” cellular tissue) in the tree trunks and also led to the precipitation of minerals in those cellular cavities, thereby locking the mineral into those cell structures.

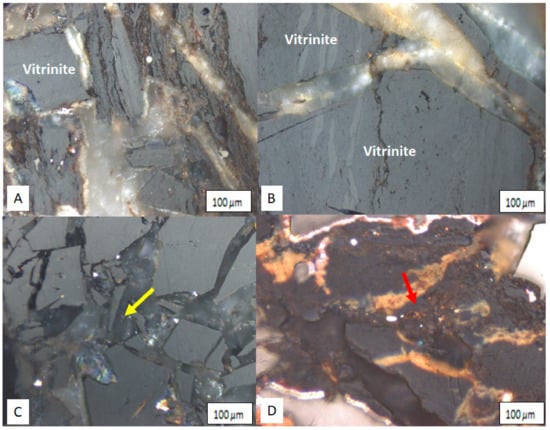

The observed mineral matter ranges from 21 to 26 vol.% in the top samples (Figure 9). The results show that sample MM-1 (Middle middle seam) has the lowest silica mineral percentage of about 2.8 vol.%. Silicate minerals (which can be quartz or clay) are the most abundant and represent an average of approximately 21.7 vol.% of the total mineral matter associated with coal in the upper-middle seam. Mineral genesis is complex; they may have a detrital origin or may be a secondary product from aqueous solutions [31]. Additionally, the top samples have a high amount of epigenetic carbonate minerals, which are minerals deposited after peat formation at any time during coalification. Carbonate minerals in the samples appear to have shattered the vitrinites with the lowest effect in sample BM-2 (Bottom middle seam) and highest with 8.6 vol.% in sample TM-1 (Top middle seam). It is supposed that the secondary carbonate minerals precipitate from magma-derived fluids percolating through the coal following the emplacement of the intrusion. The textures and distribution of carbonate minerals suggest that the temperatures and pressures of the fluids may be just as significant in the developing fractures near dykes, particularly those that have multiple phases of geometries [27]. The pyrite content is also high in sample TM-1, with a concentration of about 5.4 vol.%, which is a contrast to the other samples where pyrite content is less than 1 vol.% or completely absent/not observed under the microscope. Sulfur is commonly present in the organic fraction of the coal, whereas inorganic or mineral sulfur is in the form of pyrite. Pyrite may be present as a primary as authigenic minerals in coal and black shale or as secondary pyrite as a result of the reduction of sulfur in marine waters (pyrite framboids are mostly identified in marine anoxic sediments).

Figure 9.

Photograph showing: (A) carbonate minerals with pyrites shattering vitrinite, with more clay minerals surrounding the shattering; (B) carbonate minerals with pyrites shattering vitrinite with specific example to collotelinite in darker grey shades; (C) carbonate mineral shattering vitrinite; and (D) pyrite mineral in darker yellowish-orange.

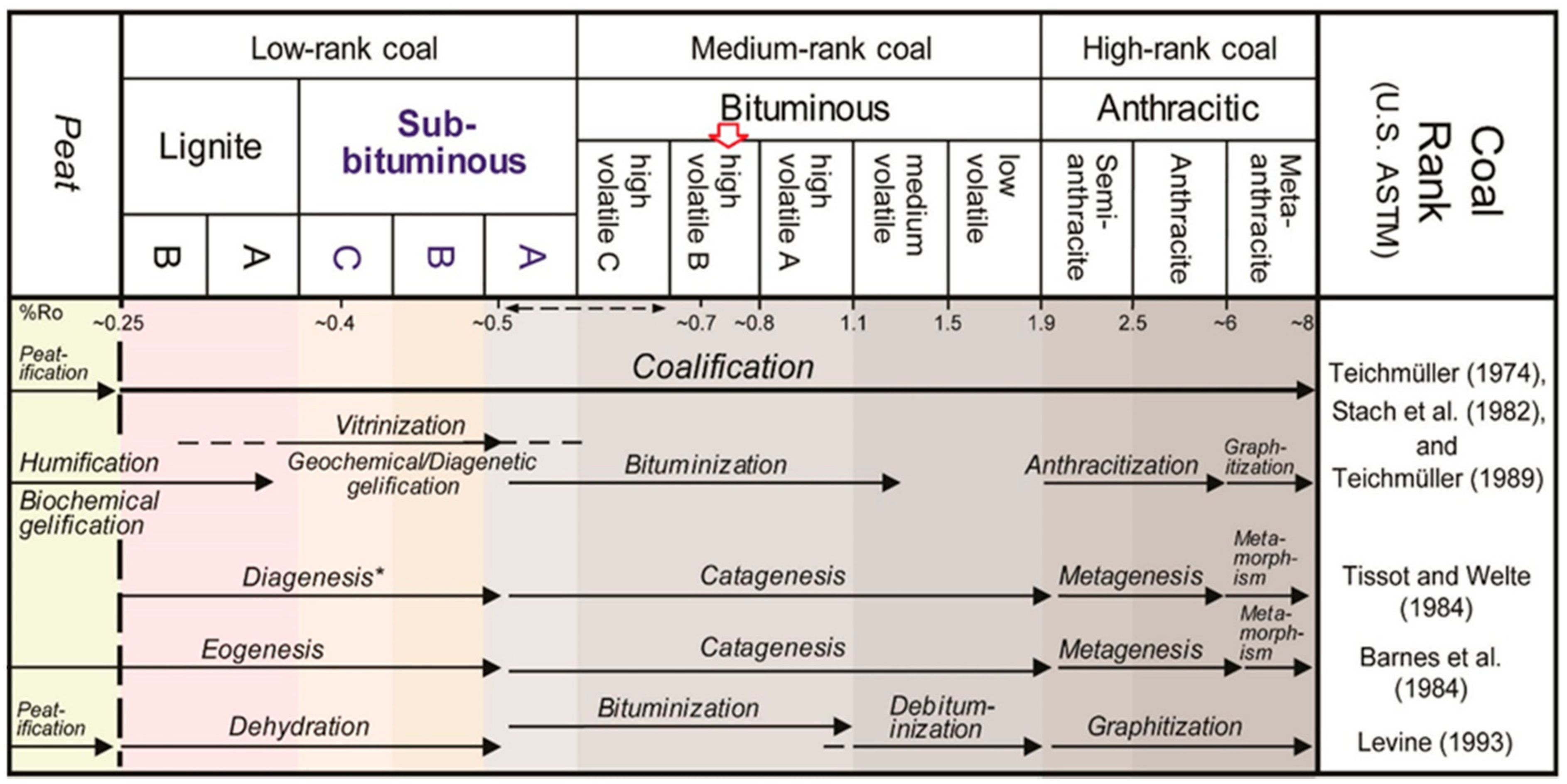

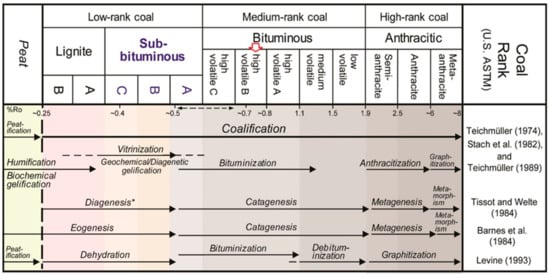

5.3. Coal Rank Determination

As indicated earlier, coal is a complex mixture of organic matter and inorganic mineral matter formed over eons from successive layers of vegetation. Based on the degree of temperature and pressure, coal is classified into four main types, or ranks: anthracite, bituminous, subbituminous, and lignite. Coal rank displays variation in the volatile matter, fixed carbon, inherent moisture, and oxygen. The percentage of carbon in coal is used to identify the rank of the coal and its position in the coal series, although no single parameter defines the rank. Typically, coal rank increases as the amount of fixed carbon increases and the amount of volatile matter and moisture decreases. Rank is the stage reached by coal in the course of its coalification. The rank depends on the maximum temperature to which the organic matter has been exposed during burial and the time it has been subjected to this temperature. Even though the heat flow from nearby intrusions may have contributed to the coalification, it is in general related to the depth of burial and the geothermal gradient [32]. The rank of the studied samples was determined using their vitrinite reflectance as shown in Table 4. The mean random vitrinite reflectance values obtained for the analyzed samples range between 0.75% and 0.80% RoVmr (mean random vitrinite reflectance), placing the samples in the medium rank C category, as per the UN-ECE in seam classification scheme (Figure 10). The medium rank C category is also referred to as the high volatile bituminous coal category. The standard deviation values are low, indicating a single population, with no blending or heat effect determined. In general, the high amount of inertinite, especially fusinite with empty cells and semi-fusinite in the coals, will pose a threat to coal mining because it aids the formation of dust during mining.

Table 4.

Interpretation of the vitrinite reactance values for the analyzed coal samples.

Figure 10.

Position of the analyzed samples in the Coal Classification of the Economic Commission for Europe (UN-ECE) in coal classification scheme.

6. Conclusions

The petrographic characterization revealed that vitrinite is the dominant maceral group in the coals, representing up to 81–92 vol.% (mmf) of the total sample. Collotellinite is the dominant vitrinite maceral, with a total count varying between 52.4 vol.% (mmf) and 74.9 vol.% (mmf), followed by corpogelinite, collodetrinite, tellinite, and pseudovitrinite with a count ranging between 0.8 and 19.4 vol.% (mmf), 1.5 and 17.5 vol.% (mmf), 0.8 and 6.5 vol.% (mmf), and 0.3 and 5.9 vol.% (mmf), respectively. The dominance of collotellinite gives a clear indication that the coals are derived from the parenchymatous and woody tissues of roots, stems, and leaves. The mean random vitrinite reflectance values range between 0.75 and 0.76%, placing the coals in the medium rank category (also known as the high volatile bituminous coal) based on the UN-ECE coal classification scheme. The inertinite content is low, ranging between 4 and 16 vol.% (mmf), and it is dominated by fusinite with the count of about 1–7 vol.% (mmf). The high amount of inertinite, especially fusinite with empty cells and semi-fusinite in the coals, will pose a threat to coal mining because it aids the formation of dust. This project could perhaps serve as a basis for future study on the nature and rank of coal in the Madzaringwe Formation. Since the thin coal seams in the Vele colliery are of medium rank under complex geological settings, it is recommended that further and detailed coal characterization study be carried out in the Madzaringwe Formation as well as the neighboring formations because the area could pose or holds a better opportunity for potentially exploitable coal deposits. It is also strongly suggested that detailed diagenetic study of coal (biochemical coalification) be carried on the Madzaringwe coal so as to determine the degree of the coalification. Considering the fact that different rank parameters of coal change with the degree of coalification, the character or rank of coal in any deposit is a function of the combined effect of the processes that formed it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.D. and C.B.; methodology, E.D. and C.B.; software, E.D. and C.B.; validation, E.D. and C.B.; formal analysis, E.D.; investigation, E.D. and C.B.; resources, E.D.; data curation, E.D. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.; writing—review and editing, E.D. and C.B.; visualization, E.D. and C.B.; supervision, C.B.; project administration, C.B.; funding acquisition, E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Mining Qualification Authority (MQA) South Africa for funding this research project.

Data Availability Statement

Not necessary or applicable because no additional data or supplementary data is associated with this paper.

Acknowledgments

The management of the Coal of Africa (Vele Colliery) is appreciated for the opportunity access to the boreholes and mine site for sampling. Also, Nikki Wagner of the University of Johannesburg is appreciated for the coal analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Catuneanu, O.; Wopfner, H.; Eriksson, P.G.; Cairncross, B.; Rubidge, B.S.; Smith, R.M.H.; Hancox, P.J. The Karoo basins of south-central Africa. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2005, 43, 211–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordy, E.M.; Catuneanu, O. Sedimentology and palaeontology of upper Karoo aeolian strata (Early Jurassic) in the Tuli Basin, South Africa. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2002, 35, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Ruiz, I.; Flores, D.; Mendonça Filho, J.G.; Hackley, P.C. Review and update of the applications of organic petrology: Part 1, geological applications. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 99, 54–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Ruiz, I.; Ward, C.R. Basic factors controlling coal quality and technological behavior of coal. Appl. Coal Petrol. 2008, 87, 19–59. [Google Scholar]

- Brandl, G.; McCourt, S. A lithostratigraphic subdivision of the Karoo Sequence in the north-eastern Transvaal. Ann. Geol. Surv. South Afr. 1980, 14, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Snyman, C.P. The role of coal petrography in understanding the properties of South African coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 1989, 14, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, J.G.D.; Smith, W.H. Coal petrography in the evaluation of South African coals. Coal Gold Base Miner. 1977, 102, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hancox, P.J.; Götz, A.E. South Africa’s coalfields—A 2014 perspective. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 132, 170–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.M.; Key, R.M. The Tectonic Development of the Limpopo Mobile belt and the Evolution of the Archaean Cratons of Southern Africa. Dev. Precambrian Geol. 1981, 4, 185–212. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.R.; Van Vuuren, C.J.; Hegenberger, W.F.; Key, R.; Show, U. Stratigraphy of the Karoo Supergroup in southern Africa: An overview. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 1996, 23, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordy, E.M.; Hancox, P.J.; Rubidge, B.S. The contact of the Molteno and Elliot formations through the main Karoo Basin, South Africa: A second-order sequence boundary. South Afr. J. Geol. 2005, 108, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulkeridis, T.; Clauer, N.; Kröner, A.; Reimer, T.; Todt, W. Characterization, provenance, and tectonic setting of Fig Tree greywackes from the Archaean Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. Sediment. Geol. 1999, 124, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyegunhi, C.; Liu, K.; Gwavava, O. Geochemistry of sandstones and shales from the Ecca Group, Karoo Supergroup, in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: Implications for provenance, weathering and tectonic setting. Open Geosci. 2017, 2017, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.G.; Schereiber, U.M.; Reczko, B.F.; Synman, C.P. Petrography and geochemistry of sandstones interbedded with the Rooiberg Felite Group (Transvaal, South Africa): Implications for provenance and tectonic setting. J. Sediment. Res. 1999, 64, 836–846. [Google Scholar]

- Vail, J.R.; Dodson, M.H. Geochronology of Rhodesia. South Afr. J. Geol. 1969, 72, 79–113. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, K.; Dewey, J.F. Plume-generated triple junctions: Key indicators in applying plate tectonics to old rocks. J. Geol. 1973, 81, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, L.; Woodford, A. Morpho-tectonics and mechanism of emplacement of the dolerite rings and sills of the western Karoo, South Africa. South Afr. J. Geol. 1999, 102, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wronkiewicz, D.J.; Condie, K.C. Geochemistry and mineralogy of sediments from the Ventersdorp and Transvaal Supergroups, South Africa: Cratonic evolution during the early Proterozoic. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaza, N.; Liu, K.; Zhao, B. Facies Analysis and Depositional Environments of the Late Palaeozoic Coal-Bearing Madzaringwe Formation in the Tshipise-Pafuri Basin, South Africa. Int. Sch. Res. Not. Geol. 2013, 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, W.C.; Flint, S.S.; Hodgson, D.M. Sequence stratigraphy of an argillaceous, deepwater basin-plain succession: Vischkuil Formation (Permian), Karoo Basin, South Africa. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2010, 27, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 7404-2. Methods for the Petrographic Analysis of Coals—Part 2: Methods of Preparing Coal Samples; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hower, J.C.; Wagner, N.J.; Jennifer, M.K.; Drew, J.W.; Stacker, J.D.; Richardson, A.R. International Journal of Coal Geology Maceral types in some Permian Southern African coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 100, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology. The new vitrinite classification (ICCP System 1994). Fuel 1998, 77, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology. The new inertinite classification (ICCP System 1994). Fuel 1994, 82, 459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C.R. Analysis, origin and significance of mineral matter in coal: An updated review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 165, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, R.V. Abundance of organic matter in sediments: TOC, hydrodynamic equivalence, dilution and flux effects. In Sedimentary Organic Matter; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 81–118. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.C.; Cook, A.C. Coalification paths of exinite, vitrinite and inertinite. Fuel 1980, 59, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, E.; Mackowsky, M.T.; Teichmüller, M.; Taylor, G.H.; Chandra, D.; Teichmüller, R. Coal Petrology; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1982; pp. 521–535. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.; Hornung, J.; Hinderer, M.; Garzanti, E. Petrography and geochemistry of modern river sediments in an equatorial environment (Rwenzori Mountains and Albertine rift, Uganda)—Implications for weathering and provenance. Sediment. Geol. 2016, 336, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackely, P.C.; Kolak, J.J. Petrographic and Vitrinite Reflectance Analyses of a Suite of High Volatile Bituminous Coal Samples from the United States and Venezuela US Department of the Interior; Open-File Report; U.S. Geological Survey: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2008; pp. 1–36.

- Alexander, N.; Golab, A.; Adrian, C.; Hutton, D.H. The impact of igneous intrusions on coal, cleat carbonate, and groundwater composition. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2007, 64, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bibler, C.J.; Marshall, J.S.; Pilcher, R.C. Status of worldwide coal mine methane emissions and use. Int. J. Coal Geol. 1998, 35, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).