Influence of Ceramic Lumineers on Inflammatory Periodontal Parameters and Gingival Crevicular Fluid IL-6 and TNF-α Levels—A Clinical Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Lumineer Treatment

2.5. Clinical Periodontal Parameters

2.6. Collection of GCF

2.7. Assessment of Cytokine Profile

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Clinical Periodontal Parameters

3.3. Volume and Cytokine Profile of the GCF

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Clinical Significance

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Binshabaib, M.; Alharthi, S.S.; Akram, Z.; Khan, J.; Rahman, I.; Romanos, G.E.; Javed, F. Clinical periodontal status and gingival crevicular fluid cytokine profile among cigarette-smokers, electronic-cigarette users and never-smokers. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 102, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhekeir, D.F.; Al-Sarhan, R.A.; Al Mashaan, A.F. Porcelain laminate veneers: Clinical survey for evaluation of failure. Saudi Dent. J. 2014, 26, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walls, A.W. The use of adhesively retained all-porcelain veneers during the management of fractured and worn anterior teeth: Part 2. Clinical results after 5 years of follow-up. Br. Dent. J. 1995, 178, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljabbar, T.; Akram, Z.; Vohra, F.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Javed, F. Assessment of interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-Α levels in the peri-implant sulcular fluid among waterpipe (narghile) smokers and never-smokers with peri-implantitis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2018, 20, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlatanovska, K.; Dimova, C.; Zarkova-Atanasova, J. Minimally Invasive Aesthetic Solutions—Porcelain Veneers and Lumineers. Defect Diffus. Forum 2017, 376, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitthra, S.; Anuradha, B.; Pia, J.C.; Subbiya, A. Veneers−Diagnostic and Clinical Considerations: A Review. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, U.S.; Kapferer, I.; Burtscher, D.; Dumfahrt, H. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers for up to 20 years. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2012, 25, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Paek, J.; Kim, S.-Y. Splinted Porcelain Laminate Veneers with a Natural Tooth Pontic: A Provisional Approach for Conservative and Esthetic Treatment of a Challenging Case. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, E257–E265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pneumans, M. The Clinical Performance of Veneer Restorations and their Influence on the Periodontium. Influ. Periodontium 1997, 1, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kihn, P.W.; Barnes, D.M. The clinical longevity of porcelain veneers: A 48-month clinical evaluation. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1998, 129, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.H.; Shah, J.H.; Patel, S.A.; Shah, H.P. Esthetic management of fluoresced teeth with ceramic veneers and direct composite bonding—An overview and a case presentation. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZD28–ZD30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhyvotovskyi, I.V.; Sylenko, Y.I.; Khrebor, M.V.; Shlykova, O.A.; Izmailova, O.V. Dynamics of the level of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the crevicular fluid after direct and indirect restoration. Ukr. Dent. Alm. 2020, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C.J.; Wheater, M.A.; Jacobs, L.C.; Litonjua, L.A. Interleukins in gingival crevicular fluid in patients with definitive full-coverage restorations. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2014, 35, e18–e24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kourkouta, S.; Walsh, T.T.; Davis, L.G. The effect of porcelain laminate veneers on gingival health and bacterial plaque characteristics. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1994, 21, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Polizzi, A.; Patini, R.; Ferlito, S.; Alibrandi, A.; Palazzo, G. Association among serum and salivary A. actinomycetemcomitans specific immunoglobulin antibodies and periodontitis. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Anastasi, G.P.; Favaloro, A.; Milardi, D.; Vermiglio, G.; Vita, G.; Cordasco, G.; Cutroneo, G. Immunohistochemical analysis of TGF-β1 and VEGF in gingival and periodontal tissues: A role of these biomarkers in the pathogenesis of scleroderma and periodontal disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isola, G.; Giudice, A.L.; Polizzi, A.; Alibrandi, A.; Murabito, P.; Indelicato, F. Identification of the different salivary Interleukin-6 profiles in patients with periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021, 122, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, Z.; Abduljabbar, T.; Abu Hassan, M.I.; Javed, F.; Vohra, F. Cytokine Profile in Chronic Periodontitis Patients with and without Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dis. Markers 2016, 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, J.S.; Kinane, D.F.; Adonogianaki, E. Gingival health associated with porcelain veneers on maxillary incisors. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 1991, 1, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainamo, J.; Bay, I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int. Dent. J. 1975, 25, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Silness, J.; Löe, H. Periodontal Disease in Pregnancy II. Correlation Between Oral Hygiene and Periodontal Condition. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1964, 22, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamoudi, N.; Alsahhaf, A.; Al Deeb, M.; Alrabiah, M.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Effect of scaling and root planing on the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-9, IL-10, and IL-13) in the gingival crevicular fluid of electronic cigarette users and non-smokers with moderate chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2020, 50, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, F.; Akram, Z.; Bukhari, I.; Sheikh, S.; Riny, A.; Javed, F. Comparison of Periodontal Inflammatory Parameters and Whole Salivary Cytokine Profile Among Saudi Patients with Different Obesity Levels. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2018, 38, e119–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Bolay, Ş.; Hickel, R.; Ilie, N. Shear bond strength of porcelain laminate veneers to enamel, dentine and enamel-dentine complex bonded with different adhesive luting systems. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, S.; Bagis, B. Colour stability of laminate veneers: An in vitro study. J. Dent. 2011, 39 (Suppl. 3), e57–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, S.; Bagis, B. Effect of resin cement and ceramic thickness on final color of laminate veneers: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 109, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani, V.; Ibrahim, H.; Al-Harthi, L.; Lyons, K.M. The periodontal restorative interface: Esthetic considerations. Periodontology 2000 2017, 74, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.I. Laminados Cerâmicos Cimentados Sobre Dentes Não Preparados. Estudo Clínico, Prospectivo e Longitudinal Sobre a Adaptação Marginal e Avaliação do Comportamento Periodontal Pelo Uso de Biomarcadores do Fluido Gengival Crevicular. Available online: https://repositorio.unesp.br/handle/11449/180305 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Celik, N.; Askın, S.; Gul, M.A.; Seven, N. The effect of restorative materials on cytokines in gingival crevicular fluid. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 84, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennermo, M.; Held, C.; Stemme, S.; Ericsson, C.-G.; Silveira, A.; Green, F.; Tornvall, P. Genetic Predisposition of the Interleukin-6 Response to Inflammation: Implications for a Variety of Major Diseases? Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 2136–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tymkiw, K.D.; Thunell, D.H.; Johnson, G.K.; Joly, S.; Burnell, K.K.; Cavanaugh, J.E.; Brogden, K.A.; Guthmiller, J.M. Influence of smoking on gingival crevicular fluid cytokines in severe chronic periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 38, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadi, A.; Rangarajan, V.; Savadi, R.C.; Satheesh, P. Biologic Perspectives in Restorative Treatment. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2011, 11, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, P. Restorative margins and periodontal health: A new look at an old perspective. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1987, 57, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, R.; Dennison, J.B.; Garcia, D.; Yaman, P. Gingival Health of Porcelain Laminate Veneered Teeth: A Retrospective Assessment. Oper. Dent. 2019, 44, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilardi, L.F.; Soares, P.; Werner, A.; de Jager, N.; Pereira, G.K.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Rippe, M.P.; Valandro, L.F. Fatigue performance of distinct CAD/CAM dental ceramics. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 103, 103540. [Google Scholar]

- Peumans, M.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Lambrechts, P.; Vanherle, G. Porcelain veneers: A review of the literature. J. Dent. 2000, 28, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daood, U.; Abduljabbar, T.; Al-Hamoudi, N.; Akram, Z. Clinical and radiographic periodontal parameters and release of collagen degradation biomarkers in naswar dippers. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabir Hussain, A. Oral Health and Dental Veneers: Clinical Tips. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Dastidar, R.; Gillam, D.G.; Islam, S.S. Socio-Demographic and Oral Health Related Risk Factors for Periodontal Disease in Inner North East London (INEL) Adults: A Secondary Analysis of the INEL Data. Int. J. Dent. Oral Health 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östberg, A.-L.; Halling, A.; Lindblad, U. Gender differences in knowledge, attitude, behavior and perceived oral health among adolescents. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1999, 57, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omari, Q.D.; Hamasha, A.A.-H. Gender-Specific Oral Health Attitudes and Behavior among Dental Students in Jordan. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2005, 6, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, A.H. Determination of Interleukin-1β (IL-1 β) and Interleukin-6(IL6) in Gingival Crevicular Fluid in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2015, 14, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, P.A.; Wilson, N.H. Preparations for porcelain laminate veneers in general dental practice. Br. Dent. J. 1998, 184, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowashi, Y.; Jaccard, F.; Cimasoni, G. Sulcular polymorphonuclear leucocytes and gingival exudate during experimental gingivitis in man. J. Periodontal Res. 1980, 15, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, S.L. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings from NHANES III Tobacco control View project Global Adult Tobacco Survey View project. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, M.A. Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2002, 60, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campus, G.; Salem, A.; Uzzau, S.; Baldoni, E.; Tonolo, G. Diabetes and Periodontal Disease: A Case-Control Study. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 27 |

| Age range (Years) | 23.5–40.6 |

| Gender (F/M) | 16/11 |

| Number of Lumineers | 288 |

| Maxilla/Mandible | 196/92 |

| Parameters | Baseline (Control) | 4 Weeks | 12 Weeks | 24 Weeks | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean PI (%) | 15.2 ± 4.3 A | 25.4 ± 6.7 B | 17.8 ± 7.3 A | 17.1 ± 4.5 A | <0.05 |

| Mean BOP (%) | 12.8 ± 5.6 A | 28.6 ± 7.8 B | 16.1 ± 8.3 A | 16.5 ± 5.5 A | <0.05 |

| Mean PPD (mm) | 2.4 ± 0.5 A | 2.6 ± 0.7 A | 2.8 ± 0.9 A | 2.7 ± 0.6 A | >0.05 |

| Mean CAL (mm) | 1.1 ± 0.5 A | 1.1 ± 0.8 A | 1.3 ± 0.5 A | 1.3 ± 0.7 A | >0.05 |

| Mean GCF volume (μL) | 0.6 ± 0.2 A | 1.3 ± 0.6 B | 0.8 ± 0.3 A | 0.8 ± 0.5 A | <0.05 |

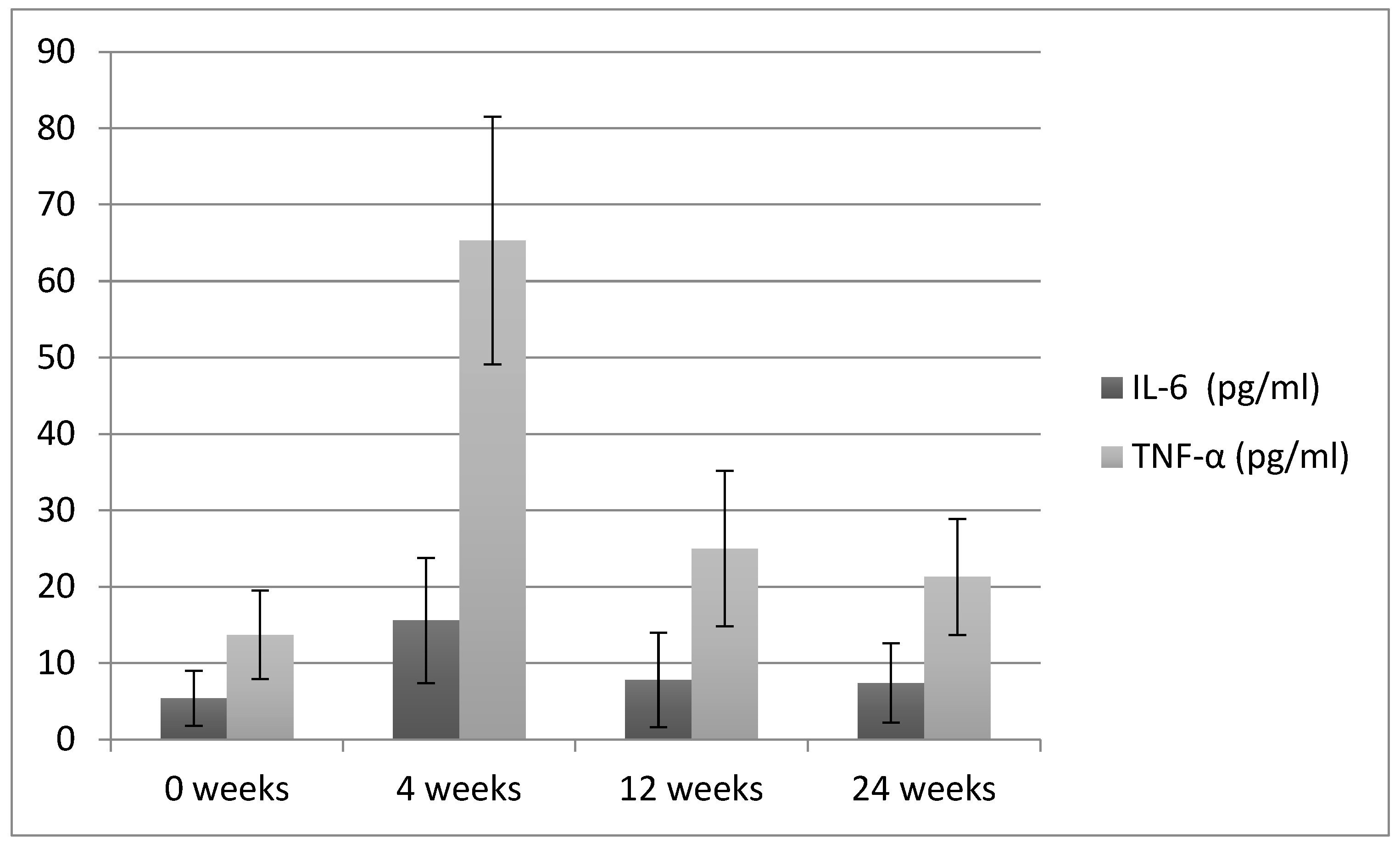

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 5.4 ± 3.6 A | 15.6 ± 8.2 B | 7.8 ± 6.2 A | 7.4 ± 5.2 A | <0.05 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 13.7 ± 5.8 A | 65.3 ± 16.2 B | 25 ± 10.2 C | 21.3 ± 7.6 C | <0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alrahlah, A.; Altwaim, M.; Alshuwaier, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Alzahrani, K.M.; Attar, E.A.; Alshahrani, A.; Abrar, E.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Influence of Ceramic Lumineers on Inflammatory Periodontal Parameters and Gingival Crevicular Fluid IL-6 and TNF-α Levels—A Clinical Trial. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062829

Alrahlah A, Altwaim M, Alshuwaier A, Eldesouky M, Alzahrani KM, Attar EA, Alshahrani A, Abrar E, Vohra F, Abduljabbar T. Influence of Ceramic Lumineers on Inflammatory Periodontal Parameters and Gingival Crevicular Fluid IL-6 and TNF-α Levels—A Clinical Trial. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(6):2829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062829

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrahlah, Ali, Manea Altwaim, Abdulaziz Alshuwaier, Malik Eldesouky, Khaled M. Alzahrani, Esraa A. Attar, Abdullah Alshahrani, Eisha Abrar, Fahim Vohra, and Tariq Abduljabbar. 2021. "Influence of Ceramic Lumineers on Inflammatory Periodontal Parameters and Gingival Crevicular Fluid IL-6 and TNF-α Levels—A Clinical Trial" Applied Sciences 11, no. 6: 2829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062829