Geminated Maxillary Incisors: The Success of an Orthodontic Conservative Approach: 15 Years Follow-Up Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

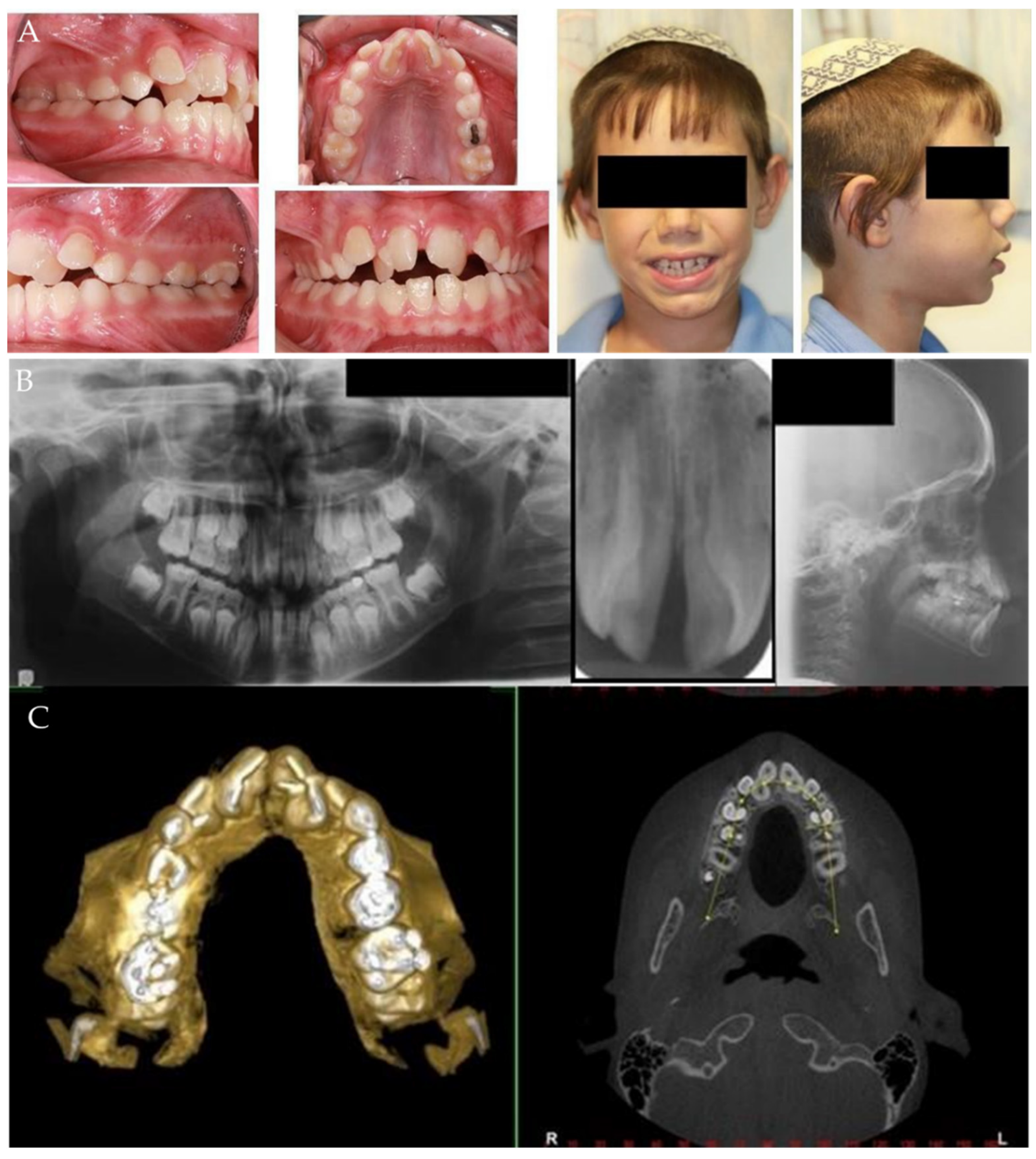

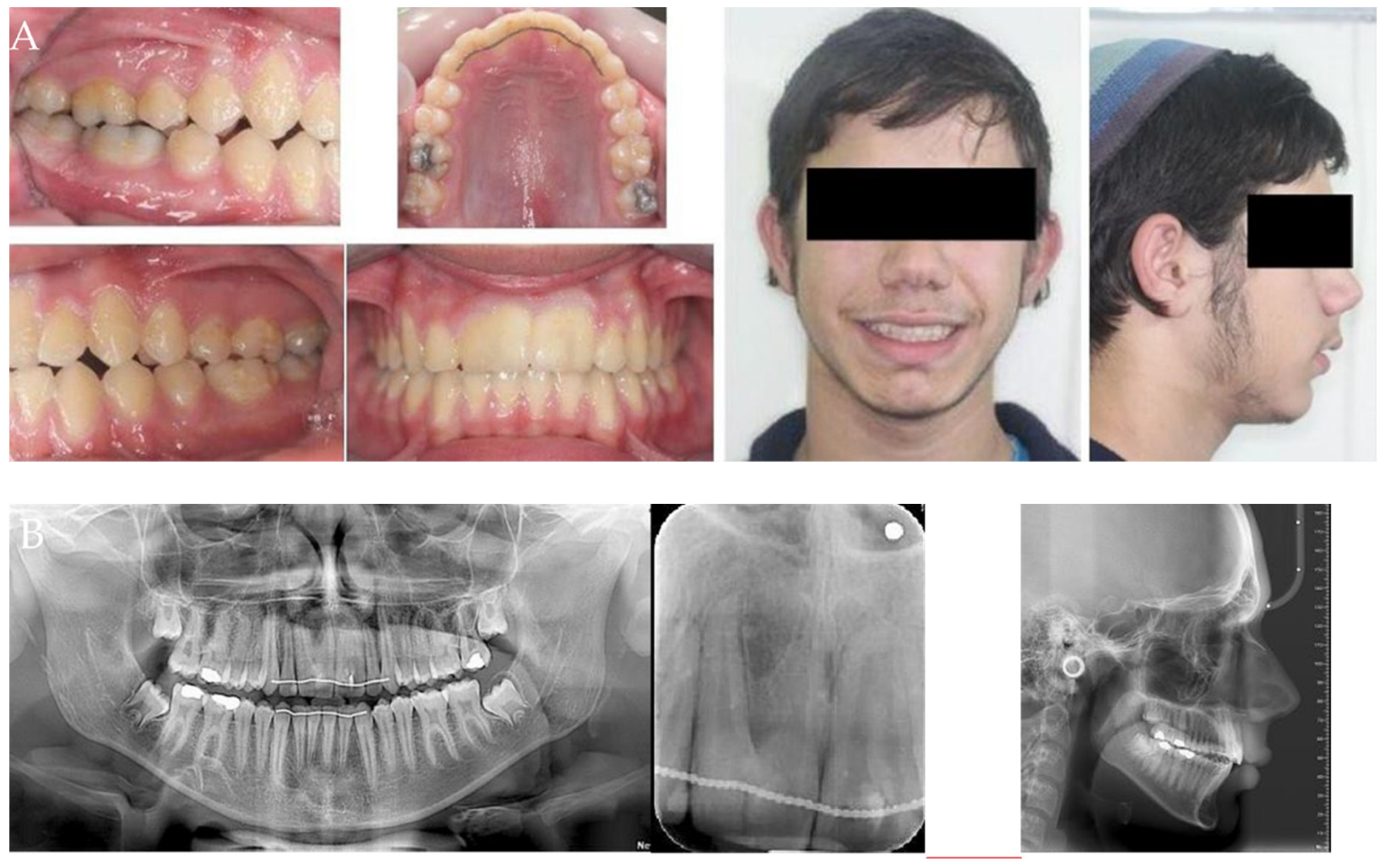

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- Patients

- (b)

- Gemination Characteristics

- (1)

- SNA (Sella, Nasion, A point) indicates the position of the maxilla mandible (whether or not it is normal, prognathic, or retrognathic);

- (2)

- SNB (Sella, Nasion, B point) Indicates the position of the mandible (whether or not it is normal, prognathic, or retrognathic);

- (3)

- ANB (A point, Nasion, B point) indicates whether the skeletal relationship between the maxilla and mandible is a normal skeletal class I (+2 degrees), a skeletal class II (+4 degrees or more), or skeletal class III (0 or negative) relationship;

- (4)

- Lower facial height to indicate facial proportions;

- (5)

- Angle between Frankfort horizontal line and the line intersecting Gonion–Menton;

- (6)

- Upper incisors inclination;

- (7)

- Lower incisors inclination.

- (c)

- Treatment Protocol and Technique

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Finkelstein, T.; Shapira, Y.; Bechor, N.; Shpack, N. Surgical and orthodontic treatment of a fused maxillary central incisor and supernumerary tooth. J. Clin. Orthod. JCO 2014, 48, 654–658. [Google Scholar]

- Gazit, E.; Lieberman, A.M. Macrodontia of maxillary central incisors: Case reports. Quintessence Int. 1991, 22, 883–887. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall, M.; Philip, C.; Aboudharam, G. Orthodontic treatment of bilateral geminated maxillary permanent incisors. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, F.N.; Hazz’a, A.M. An unusal case of talon’s cusp on geminated tooth. J. Can Dent. Assoc. 2001, 67, 263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Altug-Atac, A.T.; Erdem, D. Prevalence and distribution of dental anomalies in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 131, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, C.O.; Mourino, A.P. Management of a supernumerary tooth fused to a permanent maxillary central incisor. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1986, 61, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, L.A.G.; Firoozmand, L.M.; Almeida, J.D. Double teeth in primary dentition: Report of two clinical cases. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2008, 13, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock, N.; Wigler, R.; Kaufman, A.Y.; Lin, S.; Naaj, I.A.-E.; Aizenbud, D. Fusion of Central Incisors with Supernumerary Teeth: A 10-year Follow-up of Multidisciplinary Treatment. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. Macrodontic Incisors Aetiology, Clinical features and Management. Synopses 2006, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shokri, A.; Baharvand, M.; Mortazavi, H. The largest bilateral gemination of permanent maxillary central incisors: Report of a case. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2013, 5, e295–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohenca, N.; Stabholz, A. Decoronation? A conservative method to treat ankylosed teeth for preservation of alveolar ridge prior to permanent prosthetic reconstruction: Literature review and case presentation. Dent. Traumatol. 2007, 23, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einy, S.; Kridin, K.; Kaufman, A.Y.; Cohenca, N. Immediate post-operative rehabilitation after decoronation. A systematic review. Dent. Traumatol. 2019, 36, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, S.; Shapira, J. Decoronation for the management of an ankylosed young permanent tooth. Dent. Traumatol. 2008, 24, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chércoles-Ruiz, A.; Sánchez-Torres, A.; Gay-Escoda, C. Endodontics, Endodontic Retreatment, and Apical Surgery Versus Tooth Extraction and Implant Placement: A Systematic Review. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, N.; Souza-Flamini, L.E.; Mendonça, I.L.; Silva, R.G.; Cruz-Filho, A.M. Geminated Maxillary Lateral Incisor with Two Root Canals. Case Rep. Dent. 2016, 2016, 3759021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, D.A.; Johnson, K.; Maroli, R.K.; James, E.P. Management of geminated maxillary lateral incisor using cone beam computed tomography as a diagnostic tool. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, E.B.; Yildirim, M.; Seymen, F.; Gencay, K.; Ozgen, M. Fused teeth: A review of the treatment options. J. Dent. Child. 2009, 76, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- David, H.T.; Krakowiak, P.A.; Pirani, A.B. Nonendodontic coronal resection of fused and geminated vital teeth: A new technique. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 1997, 83, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.F.; Festa, P.; Cantile, T.; D’Antò, V.; Ingenito, A.; Martina, R. Multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of double bilateral upper permanent incisors in a young boy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Korayem, M.; Flores-Mir, C.; Nassar, U.; Olfert, K.D.G. Implant Site Development by Orthodontic Extrusion. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, W.A. The clinical application of a tooth-size analysis. Am. J. Orthod. 1962, 48, 504–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strujic, M.; Anić-Milošević, S.; Meštrović, S.; Šlaj, M. Tooth size discrepancy in orthodontic patients among different malocclusion groups. Eur. J. Orthod. 2009, 31, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, J.E.; Maskeroni, A.; Lorton, L. Frequency of Bolton tooth-size discrepancies among orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1996, 110, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanova-Kostova, G.R.; Grancharov, M.V.; Gurgurova, G.D. Abnormality in the Morphogenesis of Tooth Development and Relationship with Orthodontic Deformities and Treatment Approaches. Case Rep. Dent. 2021, 2021, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigge, E.; Roberts, R.M.; Jamieson, L.; Dreyer, C.W.; Sampson, W.J. The psycho-social impact of malocclusions and treatment expectations of adolescent orthodonticpatients. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 38, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.D. Fusion and duplication: Orthodontic, treatment of a developmental anomaly. Eur. J. Orthod. 1987, 9, 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi, M.; Kaufman, A.; Einy, S. The diagnostic and treatment challenges associated with traumatized intruded permanent incisors: A case report. Quintessence Int. 2015, 46, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Einy, S.; Kaufman, A.Y.; Yoshpe, M.; Philosoph, N.; Aizenbud, D.; Lin, S. Decoronation of an ankylosed tooth: Postoperative restoration by means of an intermediate fixed orthodontic laboratory device. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pair, J. Movement of a maxillary central incisor across the midline. Angle Orthod. 2011, 81, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashim, H.A. Orthodontic Treatment of Fused and Geminated Central Incisors: A Case Report. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2004, 5, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Procedures | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosthetic+Surgical (non-conservative) | Extraction Anterior alveolar augmentation Implant placement | Superior aesthetics | Age 18 and older Anterior alveolar bone loss Multi-disciplinal All life management Expensive |

| Prosthetic+Endodontic (fairly conservative) | Reshaping Root canal tx. Restoration Decoronation | Fast Superior aesthetics? | Age 18 and older Possible root canal failure Multi-disciplinal All life management Expensive |

| Orthodontic (very conservative) | Distalization Maxillary expansion Minor incisor proclination Interproximal reduction (possibly) | Younger age Tooth material conservation No surgical intervention Orthodontic involvement only Stable Reasonable Cost | A minor aesthetic defect Prolonged treatment No class I relationship |

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at start of treatment | 10 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 11 |

| Sex | M | F | M | F | F |

| Geminated tooth | 11,21 | 11,21 | 11,21 | 22 | 42 |

| Angle classification | class II div 1 | class II div 1 | class I | class II div 1 | class II div 1 |

| M-D width of geminated incisors | 14/14 | 10.5/12 | 11.5/12 | 11.5 | 9 |

| Transverse relationship | bilateral X-bite | normal | normal | bilateral X-bite | normal |

| Parameters | Pre | Post | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SNA * | 890 | 930 |

| 2 | SNB ** | 810 | 860 |

| 3 | ANB *** | 80 | 70 |

| 4 | Lower facial height | 58% | 55% |

| 5 | Mandibular plane angle | 200 | 250 |

| 6 | Upper 1 to SN | 1100 | 1100 |

| 7 | Lower 1 to MP | 1000 | 920 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Einy, S.; Avezov, K.; Aizenbud, D. Geminated Maxillary Incisors: The Success of an Orthodontic Conservative Approach: 15 Years Follow-Up Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031389

Einy S, Avezov K, Aizenbud D. Geminated Maxillary Incisors: The Success of an Orthodontic Conservative Approach: 15 Years Follow-Up Study. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(3):1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031389

Chicago/Turabian StyleEiny, Shmuel, Katia Avezov, and Dror Aizenbud. 2022. "Geminated Maxillary Incisors: The Success of an Orthodontic Conservative Approach: 15 Years Follow-Up Study" Applied Sciences 12, no. 3: 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031389