Robotic Magnetorheological Finishing Technology Based on Constant Polishing Force Control

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Error of Removal Function

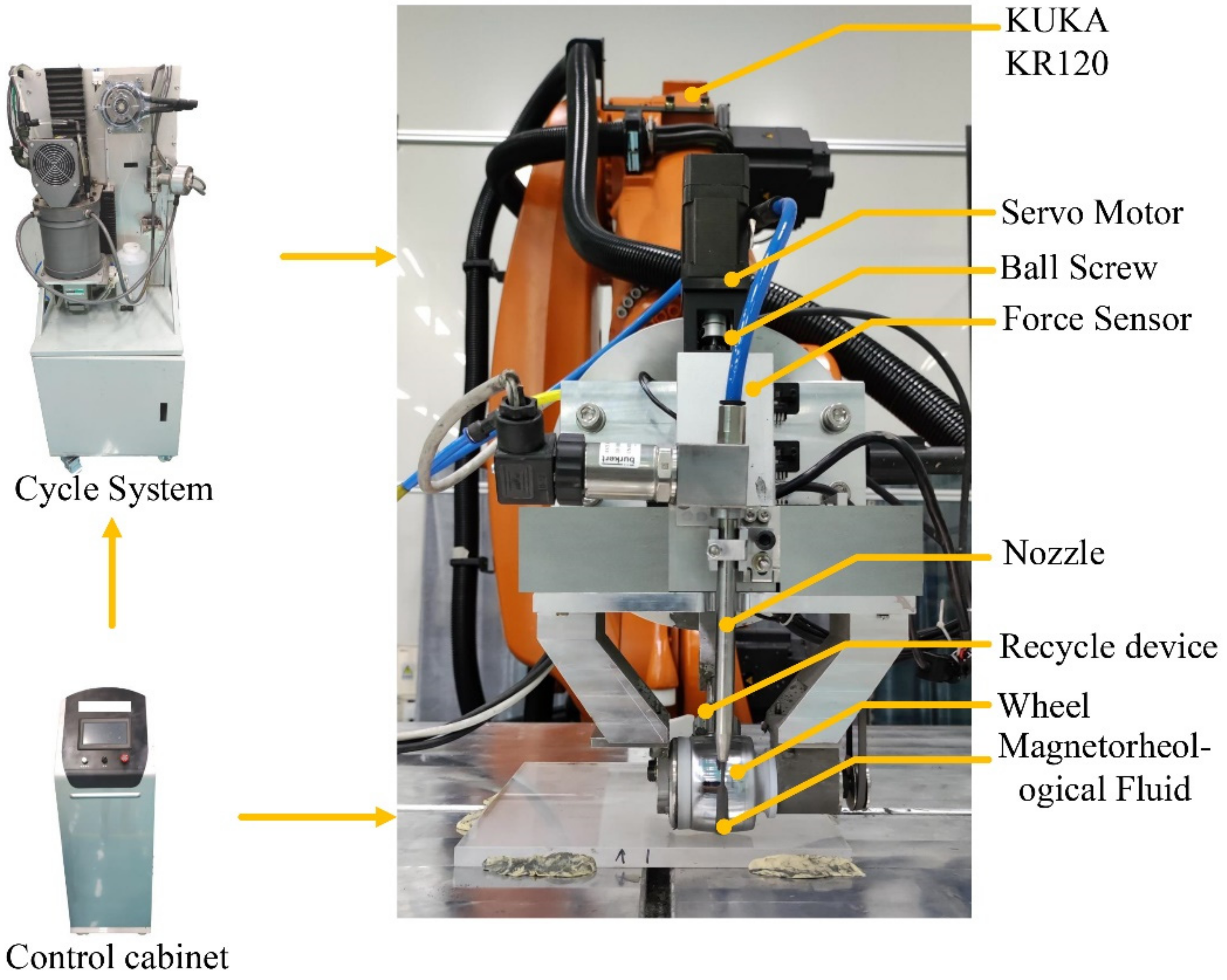

3. Force-Controlled End-Effector

3.1. Mechanical Design

3.2. Control System Modeling

3.3. Controller Design

3.4. Control Simulation

4. Experiment Setup and Results

4.1. Constant Force Control with ADRC

4.2. The Stability of Magnetorheological Polishing with Constant Force Control

4.3. Deterministic Magnetorheological Polishing with Constant Force Control

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shujing, S.; Jinfei, H.; Hequan, Z. New Progress of Magnetorheological Finishing. Mech. Eng. 2018, 7, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chunlin, M.; Lambropoulos, J.C.; Jacobs, S.D. Process parameter effects on material removal in magnetorheological finishing of borosilicate glass. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, 1951–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ci, S.; Yifan, D.; Xiaoqiang, P. Model and algorithm based on accurate realization of dwell time in magnetorheological finishing. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, 3676–3683. [Google Scholar]

- Zhichao, D.; Haobo, C.; Hon-Yuen, T. Modified dwell time optimization model and its applications in subaperture polishing. Appl. Opt. 2014, 53, 3213–3224. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Hua, D.; Wang, B.; Yang, C.; Hnydiuk-Stefan, A.; Królczyk, G.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. The Roles of Magnetorheological Fluid in Modern Precision Machining Field: A Review. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Jiao, J.C.; Li, B. Overview of high-precision operation equipment and technology for aerospace manufacturing robots. J. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2020, 52, 341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Belchior, J.; Guillo, M.; Courteille, E.; Maurine, P.; Leotoing, L.; Guines, D. Off-line compensation of the tool path deviations on robotic machining: Application to incremental sheet forming. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2013, 29, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klimchik, A.; Pashkevich, A.; Chablat, D.; Hovland, G. Compliance error compensation technique for parallel robots composed of non-perfect serial chains. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2013, 29, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiaojia, S.; Zhang, F.M.; Qu, X.H.; Liu, B.L.; Wang, J.L. Position and Attitude Measurement and Online Errors Compensation for KUKA Industrial Robots. J. Mech. Eng. 2017, 53, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Feng, X.; Xu, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Yan, S.; Ding, H. Robotic grinding of complex components: A step towards efficient and intelligent machining—Challenges, solutions, and applications. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 65, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Lin, H.-I. Development of robotic polishing/fettling system on ceramic pots. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 17298814211012851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecher, C.; Tuecks, R.; Zunke, R.; Wenzel, C. Development of a force controlled orbital polishing head for free form surface finishing. Prod. Eng. 2010, 4, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuejun, Z.; Longxiang, L.; Donglin, X.; Chi, S.; Bo, A. Development and Application of MRF Based on Robot Arm. EPJ Web Conf. 2019, 215, 06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, C.; Qin, S. End Position Detection of Industrial Robots Based on Laser Tracker. Instrum. Mes. Métrol. 2019, 18, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; Sparks, T.E.; Chen, X.; Liou, F.W. Industrial Robot Trajectory Accuracy Evaluation Maps for Hybrid Manufacturing Process Based on Joint Angle Error Analysis. Adv. Robot. Autom. 2018, 7, 1000183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M.; Qi, B.C.; Li, F.C.; Shen, Z.Q.; Li, X.R. Measurement of and Reverse Compensation for Spatial Position Error of Industrial Robots. J. Test. Eval. 2014, 43, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, F.W. The theory and design of plate glass polishing machines. J. Soc. Glass Technol. 1927, 11, 214–256. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, A.B. Mechanisms of Material Removal in Magnetorheological Finishing (MRF) of Glass. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Mechancial Engineering, Materials Science Program, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chunlin, M.; Shafrir, S.N.; Lambropoulos, J.C.; Mici, J.; Jacobs, S.D. Shear stress in magnetorheological finishing for glasses. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, B.; Gupta, B.K. Friction, wear, and lubrication. In Handbook of Triboloty: Materials, Coatings, and Surface Treatments; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Chapter 2; p. 2.11, Table 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Yu, P.; Yan, Q. Experimental Investigations on the Polishing Forces Characteristics of Dynamic Magnetic Field Magnetorheological Effect Polishing Pad. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 54, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schinhaerl, M.; Vogt, C.; Geiss, A.; Stamp, R.; Sperber, P.; Smith, L.; Smith, G.; Rascher, R. Forces acting between polishing tool and workpiece surface in magnetorheological finishing. In Optical Engineering + Applications; SPIE: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 7060. [Google Scholar]

- Chunlin, M. Frictional Forces in Material Removal for Glasses and Ceramics Using Magnetorheological Finishing. PhD Thesis, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, N. Impedance Control; An Approach to Manipulation, Parts I, II, III, ASME. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1985, 107, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Q. From PID to Active Disturbance Rejection Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 900–906. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.; Xu, L. Transfer Function Identification. Part A: Two-Point and Three-Point Methods Based on the Step Responses. J. Qingdao Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2018, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Fan, W. Robotic Magnetorheological Finishing Technology Based on Constant Polishing Force Control. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12083737

Zhang L, Zhang C, Fan W. Robotic Magnetorheological Finishing Technology Based on Constant Polishing Force Control. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(8):3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12083737

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lin, Chunlei Zhang, and Wei Fan. 2022. "Robotic Magnetorheological Finishing Technology Based on Constant Polishing Force Control" Applied Sciences 12, no. 8: 3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12083737