A Retrospective Study on Silent Sinus Syndrome in Cone Beam-Computed Tomography Images—Author Classification Proposal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Characteristic of Study Group

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Statistical Data

3.2. Relationship between CT/CBCT Radiological Features and Final Diagnosis of SSS/CMA Pathologies

3.3. Association between Clinical Symptoms and Final Diagnosis of SSS/CMA Pathologies

3.4. Classification Proposal

- (1)

- Type 1 SSS (pure SSS = pSSS) (Figure 2) MS four (4) wall retraction, OMC not patent, opacification present;

- (2)

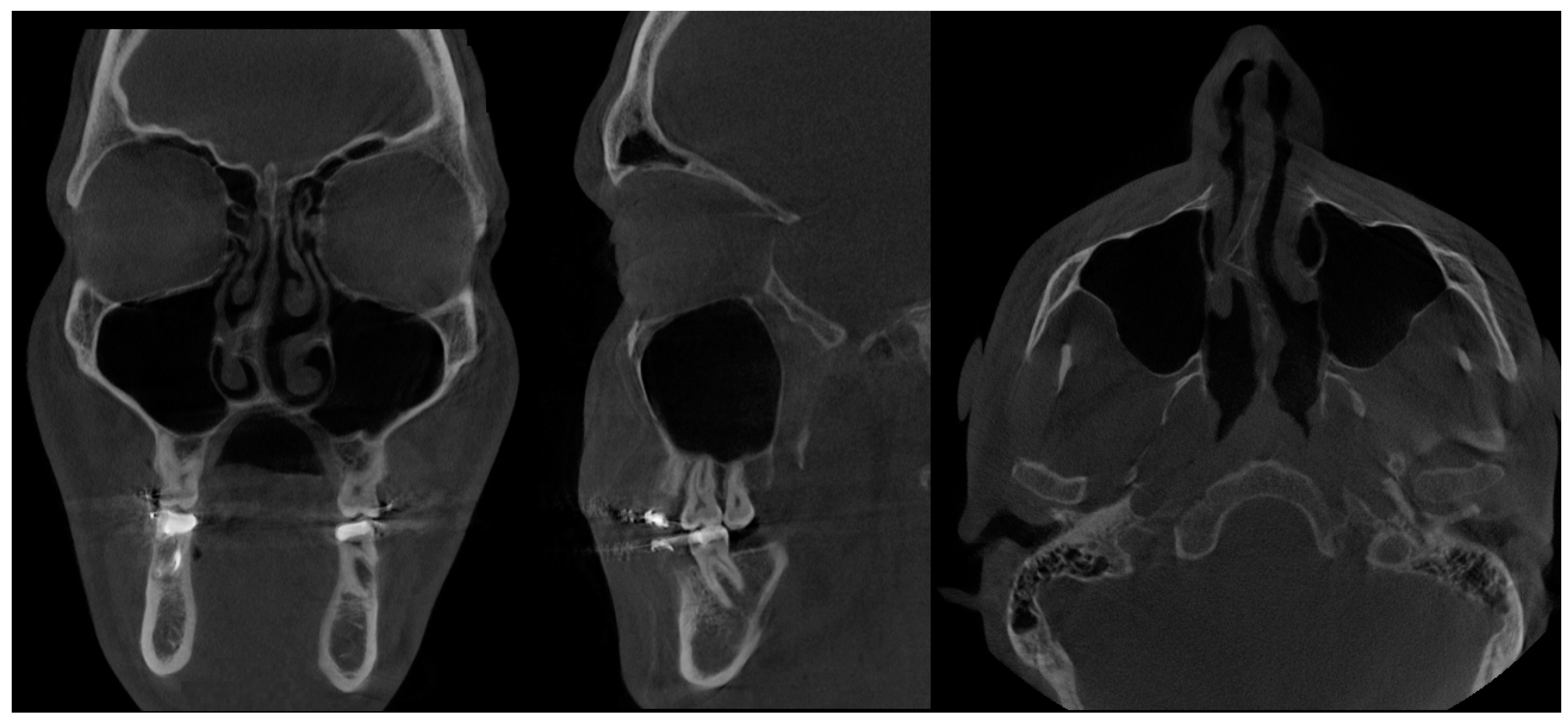

- Type 2 in-pure SSS (iSSS) (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 6) related to maxillary deformation (might be related to maxilla-mandibular skeletal class II/III deformities or others), clinically asymptomatic, not related to trauma or surgery, 1–3 MS walls retracted, OMC clear, no opacification, like suggested by Lee et al., the “not so silent sinus” [18];

- (3)

- (4)

- Type 4 CMA (an in-pure form of chronic maxillary atelectasis—iCMA) (Figure 8), corresponding to the clinical presentation of CRS, pain, and symptomatic sinus manifestation, however lacking a complete sinus opacification; OMC function might not be disturbed, 1–4 MS walls can be retracted;

- (5)

- Type 5 Mixed form SSS-CMA on both MCs (Figure 9)—present asymmetrically, combines both forms of SSS and CMA in pure or in-pure forms;

- (6)

- Type 6 atypical SSS or CMA (tsoSSS/tsoCMA—trauma, surgery, or other related SSS/CMA) of post-traumatic occurrence, post-surgical, or other iatrogenic related, such as suggested by Araslanova et al. [30];

- (7)

- Type 7 MSH = maxillary sinus hypoplasia (Figure 10 and Figure 11)—a very rare, probably somehow atypical case of complete symmetrical MS retraction and atrophy, without CRS. Possible relation to bilateral MSH—bilateral maxillary sinus hypoplasia should be considered and requires further studies [33].

3.5. Final Considerations

3.6. Commentary on the Classification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| SSS | silent sinus syndrome |

| CMA | chronic maxillary atelectasia |

| MS | maxillary sinus |

| CRS | chronic rhinosinusitis |

| OMC | osteomeatal complex |

| CBCT | cone beam-computed tomography |

| MSH | maxillary sinus hypoplasia |

| MR | magnetic resonance imaging |

| p | pure form |

| i | in-pure form |

| tso | trauma/surgery or other related form |

References

- Montgomery, W.W. Mucocele of the maxillary sinus causing enophthalmos. Eye Ear Nose Throat 1964, 43, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Soparkar, C.N.; Patrinely, J.R.; Cuaycong, M.J.; Dailey, R.A.; Kersten, R.C.; Rubin, P.A. The silent sinus syndrome: A rare cause of spontaneous enophthalmos. Ophthalmology 1994, 101, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovancevic, L.; Canadanovic, V.; Savovic, S.; Zvezdin, B.; Komazec, Z. Silent sinus syndrome-one more reason for an ophthalmologist to have a rhinologist as a good friend. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2017, 74, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaudino, S.; Di Lella, G.M.; Piludu, F.; Martucci, M.; Schiarelli, C.; Africa, E.; Salvolini, L.; Colosimo, C. CT and MRI diagnosis of silent sinus syndrome. Radiol. Med. 2013, 118, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahdani, K.; Rose, G.E. Bilateral Silent Sinus (Imploding Antrum) Syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 35, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.K.; Soparkar, C.N.; Williams, J.B.; Patrinely, J.R. Negative sinus pressure and normal predisease imaging in silent sinus syndrome. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1999, 117, 1653–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, E.S.; Salman, S.; Montgomery, W.W. Manometric study of complete ostial occlusion in chronic maxillary atelectasis. Laryngoscope 1996, 106, 1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.M.; Tami, T.A. Sinusitis-induced enophthalmos: The silent sinus syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000, 79, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, R.D.; Graham, S.M.; Carter, K.D.; Nerad, J.A. Management of the orbital floor in silent sinus syndrome. Am. J. Rhinol. 2003, 17, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, L.M. The silent sinus syndrome: Maxillary sinus atelectasis with enophthalmos and hypoglobus. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2004, 15, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, O.K.; Onaran, Z.; Muluk, N.B.; Yilmazbaş, P.; Yazici, I. Enophthalmos due to atelectasis of the maxillary sinus: Silent sinus syndrome. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2009, 20, 2156–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annino, D.J., Jr.; Goguen, L.A. Silent sinus syndrome. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2008, 16, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F. Rare Diseases of the Nose, the Paranasal Sinuses, and the Anterior Skull Base. Laryngorhinootologie 2021, 100, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G.E.; Lund, V.J. Clinical features and treatment of late enophthalmos after orbital decompression: A condition suggesting cause for idiopathic “imploding antrum” (silent sinus) syndrome. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.E.; Sandy, C.; Hallberg, L.; Moseley, I. Clinical and radiologic characteristics of the imploding antrum, or “silent sinus,” syndrome. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monos, T.; Levy, J.; Lifshitz, T.; Puterman, M. The silent sinus syndrome. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 7, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brandt, M.G.; Wright, E.D. The silent sinus syndrome is a form of chronic maxillary atelectasis: A systematic review of all reported cases. Am. J. Rhinol. 2008, 22, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Murr, A.H.; Kersten, R.C.; Pletcher, S.D. Silent sinus syndrome without opacification of ipsilateral maxillary sinus. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 2004–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albadr, F.B. Silent Sinus Syndrome: Interesting Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2020, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hura, N.; Ahmed, O.G.; Rowan, N.R. Atypical Presentation of Silent Sinus Syndrome: A Case Report and Literature Review. Allergy Rhinol. Provid. 2020, 11, 2152656719899928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosso, C.; Saibene, A.M.; Felisati, G.; Pipolo, C. Silent sinus syndrome: Systematic review and proposal of definition, diagnosis and management. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2022, 42, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar-Craig, H.; Kayhanian, H.; De Silva, D.J.; Rose, G.E.; Lund, V.J. Spontaneous silent sinus syndrome (imploding antrum syndrome): Case series of 16 patients. Rhinology 2011, 49, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, E.H.; Nesi, F.A.; Gladstone, G.J.; Levine, M.R. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1048. [Google Scholar]

- Sesenna, E.; Oretti, G.; Anghinoni, M.L.; Ferri, A. Simultaneous management of the enophthalmos and sinus pathology in silent sinus syndrome: A report of three cases. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2010, 38, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbehani, R.; Vacareza, N.; Bilyk, J.R.; Rubin, P.A.; Pribitkin, E.A. Simultaneous endoscopic antrostomy and orbital reconstruction in silent sinus syndrome. Orbit 2006, 25, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stryjewska-Makuch, G.; Goroszkiewicz, K.; Szymocha, J.; Lisowska, G.; Misiołek, M. Etiology, Early Diagnosis and Proper Treatment of Silent Sinus Syndrome Based on Review of the Literature and Own Experience. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 113.e1–113.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kass, E.S.; Salman, S.; Rubin, P.A.; Weber, A.L.; Montgomery, W.W. Chronic maxillary atelectasis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1997, 106, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vander Meer, J.B.; Harris, G.; Toohill, R.J.; Smith, T.L. The silent sinus syndrome: A case series and literature review. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, R.R.; Kingdom, T.T.; Hwang, P.H.; Smith, T.L.; Alt, J.A.; Baroody, F.M.; Batra, P.S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Bhattacharyya, N.; Chandra, R.K.; et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 22–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Araslanova, R.; Allen, L.; Rotenberg, B.W.; Sowerby, L.J. Silent sinus syndrome after facial trauma: A case report and literature review. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 1520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A.; Basyuni, S.; Santhanam, V. Not so silent sinus syndrome: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 23, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, N.; Rosenstein, J.; Dym, H. Silent Sinus Syndrome: Interesting Clinical and Radiologic Findings. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 2040–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindakhil, M.; Mupparapu, M. Cone Beam CT Evaluation of Bilateral Maxillary Sinus Hypoplasia with Unilateral Mandibular Hypertrophy. J. Orofac. Sci. 2020, 12, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Darghal, K.; Borki, R.; Essakalli, L.; Lecanu, J.-B.B. Silent Sinus Syndrome: A Retrospective Review of 11 Cases. Int. J. Med. Surg. 2014, 1, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariba, I.; Lazard, D.S.; Sain-Oulhen, C.; Lecanu, J.B. Correlation between the rate of asymmetry volume of maxillary sinuses and clinical symptomatology in the silent sinus syndrome: A retrospective study about 13 cases. Rev. Laryngol. Otol. Rhinol. 2014, 135, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Farneti, P.; Sciarretta, V.; Macrì, G.; Piccin, O.; Pasquini, E. Silent sinus syndrome and maxil-lary sinus atelectasis in children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 98, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.; Jensen, P.N.; Lopez, F.L.; Chen, L.Y.; Psaty, B.M.; Folsom, A.R.; Heckbert, S.R. Association of sick sinus syndrome with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study and Cardiovascular Health Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 109662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Typical Clinical Symptoms SSS | Typical Radiological Features in CT/CBCT of SSS |

|---|---|

| spontaneous unilateral enophthalmos | unilateral MS opacification |

| hypoglobus | MS volume reduction |

| facial asymmetry | blockage of the osteomeatal complex |

| asymptomatic maxillary sinusitis | MS walls deformation |

| diplopia in severe cases | maxillary sinus asymmetry |

| Additional Clinical Alterations in SSS | Additional Radiological Variations in SSS |

|---|---|

| disturbed eye movements | unilateral MS hypoventilation |

| asymmetry of pupillary midline | OMC with or without blockage |

| mid-face asymmetry | most MS walls retraction |

| deviated maxillary cant | MS opacification: full volume, not full volume |

| symptomatic maxillary sinusitis | ipsilateral maxillary sinus retraction |

| MS pain | collapse with/without inferior bowing of the orbital floor |

| CRS | osteomeatal complex without obstruction |

| occurrence of skeletal class II maloclusion | lateralization (lateral deviation) of the uncinate and middle turbinate, and infundibular occlusion |

| occurrence of skeletal class III maloclusion | enlarged middle meatus |

| disturbed nasal breathing | obstruction of the natural maxillary ostium |

| underdeveloped midface | retracted downward orbital floor with possible bone thickening |

| maxilary hypoplasia | demineralization of the sinus walls |

| maxillo-mandibular asymmetry | other abnormal intranasal characteristics on the affected side |

| flattening of the malar eminence | concomitant compensatory augmentation in ipsilateral orbital volume |

| deviation of the nasal septum | |

| expanded retroantral fat pad | |

| retraction of 1–3 MS walls |

| Diagnostic Criteria for SSS | Diagnostic Criteria for CMA |

|---|---|

| Enophthalmos and/or hypoglobus | Enophthalmos and/or hypoglobus |

| Maxillary sinus atelectasis or opacification on CT imaging | Maxillary sinus opacification noted on CT imaging |

| Absence of radiologic findings of CRS on CT imaging | |

| Clinical CRS not present | CRS present at examination |

| MS Pathology | MS | SSS | SSS | CMA | CMA | SSS-CMA | tsoSSS | MSH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forms | Proper Anatomy | Pure/pSSS | In-Pure/iSSS | Pure/pSSS | In-Pure/iSSS | |||

| Patients | 117 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| CBCT = 131 | 89.32% | 3.82% | 3.82% | 0.76% | 0.76% | 0.76% | 0% | 0.76% |

| SSS | CMA | SSS-CMA (n = 1) | MSH (n = 1) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure /pSSS (n = 5) | In-pure /iSSS (n = 5) | Pure /pCMA (n = 1) | In-Pure /iCMA (n = 1) | ||||

| MS atelectasis | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Unilateral MS opacification | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002 * |

| MS volume reduction | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Blockage of the osteomeatal complex | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002* |

| MS walls deformation | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| MS asymmetry | 3 (60.0) | 3 (60.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.341 |

| Unilateral MS hypoventilation | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002 * |

| Osteomeatal complex (OMC) with or without blockage | 4 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.015 * |

| SSS | CMA | SSS-CMA (n = 1) | MSH (n = 1) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure /pSSS (n = 5) | In-Pure /iSSS (n = 5) | Pure /pCMA (n = 1) | In-Pure /iCMA (n = 1) | ||||

| Spontaneous unilateral enophthalmos | 5 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.074 |

| Hypoglobus | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.821 |

| Facial asymmetry | 4 (80.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.143 |

| Asymptomatic maxillary sinusitis | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.012 * |

| Diplopia in severe cases | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| CRS presence | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.043 * |

| Mid-facial asymmetry | 5 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.029 * |

| Maxillary asymmetry | 5 (100.0) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.262 |

| Facial pain/pressure | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.089 |

| Headaches | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.042 * |

| Nasal obstruction with/without taste and smell variations | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.012 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nelke, K.; Łuczak, K.; Pawlak, W.; Łukaszewski, M.; Janeczek, M.; Pasicka, E.; Barnaś, S.; Guziński, M.; Diakowska, D.; Dobrzyński, M. A Retrospective Study on Silent Sinus Syndrome in Cone Beam-Computed Tomography Images—Author Classification Proposal. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7041. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13127041

Nelke K, Łuczak K, Pawlak W, Łukaszewski M, Janeczek M, Pasicka E, Barnaś S, Guziński M, Diakowska D, Dobrzyński M. A Retrospective Study on Silent Sinus Syndrome in Cone Beam-Computed Tomography Images—Author Classification Proposal. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(12):7041. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13127041

Chicago/Turabian StyleNelke, Kamil, Klaudiusz Łuczak, Wojciech Pawlak, Marceli Łukaszewski, Maciej Janeczek, Edyta Pasicka, Szczepan Barnaś, Maciej Guziński, Dorota Diakowska, and Maciej Dobrzyński. 2023. "A Retrospective Study on Silent Sinus Syndrome in Cone Beam-Computed Tomography Images—Author Classification Proposal" Applied Sciences 13, no. 12: 7041. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13127041

APA StyleNelke, K., Łuczak, K., Pawlak, W., Łukaszewski, M., Janeczek, M., Pasicka, E., Barnaś, S., Guziński, M., Diakowska, D., & Dobrzyński, M. (2023). A Retrospective Study on Silent Sinus Syndrome in Cone Beam-Computed Tomography Images—Author Classification Proposal. Applied Sciences, 13(12), 7041. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13127041