Abstract

To provide various applications in various domains, a large-scale cloud data center is required. Cloud computing enables access to nearly infinite computing resources on demand. As cloud computing grows in popularity, researchers in this field must conduct real-world experiments. Configuring and running these tests in an actual cloud environment is costly. Modeling and simulation methods, on the other hand, are acceptable solutions for emulating environments in cloud computing. This research paper reviewed several simulation tools specifically for cloud computing in the literature and presented the most effective simulation methods in this research domain, as well as an analysis of a variety of cloud simulation tools. Cloud computing tools such as CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports were evaluated. Furthermore, a parametric evaluation of cloud simulation tools is presented based on the identified parameters. Several 5-parameter tests were performed to demonstrate the capabilities of the cloud simulator. These results show the value of our proposed simulation system. CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports are used to evaluate host processing elements, virtual machine processing elements, cloudlet processing elements, userbase average, minimum, and maximum, and cloudlet ID Start Time, Finish Time, Average Start, and Average Finish for each simulator. The outcomes compare these five simulator metrics. After reading this paper, the reader will be able to compare popular simulators in terms of supported models, architecture, and high-level features. We performed a comparative analysis of several cloud simulators based on various parameters. The goal is to provide insights for each analysis given their features, functionalities, and guidelines on the way to researchers’ preferred tools.

1. Introduction

These days, smart devices have become prominent in supporting users in various ways. Smart devices have proven useful for the user regardless of location by using improved features and offering resources available wherever and whenever to support their needs [1]. Using hardware and software to provide a service over a network (typically the internet) is called CC. The CC is an Internet-based computing model that shares on-demand resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, apps, and services), software, and information with different user devices [2]. Users can access data and use the software with cloud storage from any computer that can connect to the internet. Google’s Gmail is an example of a cloud service provider [3]. In CC, users can access resources through the internet all the time. The users only have to pay for those resources based on their use. The cloud provider of cloud processing outsources each resource belonging to the client [4]. Researchers in CC need to perform actual experiments in their studies, setup, implementation, and experiments in the cloud; they often have a massive cost of creating a real CE. Using models and simulation software to replicate CEs and perform prerequisite testing is one viable alternative. CloudSim, CloudSim Plus [5], CloudAnalyst [6], iFogSim, and CloudReports are some of the existing cloud simulation tools discussed in this study. As a result, it is critical to select an efficient LB tool that meets QoS requirements [5]. An in-depth study on cloud simulators has been conducted in this article that identifies several parameters to evaluate them [7].

Current work is based on the analysis of HPEs, VM PEs, cloudlet PEs, UBs Avg, Min, Max, and cloudlet ID Start Time, Finish Time, Average Start, and Average Finish for each simulator, and cloud simulation tool reports are used, which circularly handle the requests of the customer based on power usage of hosts and VM consumptions, CDC, SB, and CPU usage with the host. The customer directly forwards the request through the internet, and the SB assigns the load to the DC. The SB keeps a record of all available DCs and the next DC to whom the next task shall be assigned when a customer’s request is submitted through the internet, then it forwards the request to the SB, and then the SB circularly selects the DC and assigns the job to the DC [8]. The most extensively used platform, OpenStack, is attracting more and more attention as it seeks to be competitive with other platforms such as AWS. Security issues are prevalent throughout the lifecycle of OpenStack, making security analysis an essential task [9]. The paper contribution is shown below:

- In this article, the setting of the simulators is carried out to examine the many metrics that the cloud client can measure, specifically the inbound and outbound HPE.

- This study has used a variety of simulators and experiments that may have an impact on future cloud simulation studies.

- The prominent simulators for experimental campaigns and analysis for productive work are mentioned in this study report.

- Based on this study and to the best of our knowledge, there is no succeeding work associated with other simulators.

1.1. Motivation

- Cloud computing is growing in popularity, and researchers need to conduct real-world experiments. Configuring and running these tests in an actual cloud environment is costly, so we need to remove these issues with the help of cloud simulators.

- This paper provides popular cloud simulators for modeling cloud computing environments, which enable scheduling VMs and evaluating different parameters, makespans, and execution times to reduce the complexity of testing cloud systems.

- The goal of this analysis is to make it easier for developers and researchers to analyze clouds and test different hypotheses in a controlled environment.

1.2. OpenStack Cloud Management Platform

With the help of NASA and Rackspace Hosting, OpenStack was created in 2010 as a production IaaS platform. In a DC, it controls the computing, storage, and networking resources as a dashboard that allows administrators management abilities while enabling users to provision resources using a web interface. It is possible to construct both private and public clouds using OpenStack. There are 22 versions of OpenStack, ranging from A (Austin) to V (Victoria). In a DC or a network of DCs, several sets of hypervisors, storage, and networking hardware are combined into resource pools by OpenStack. Additionally, OpenStack offers a cloud architecture that has enormous advantages in terms of robustness, performance, and compatibility when compared to cloud management platforms (Eucalyptus, Apache Cloud-Stack 4.18.0.0) [9].

1.3. Differences between OpenStack and Current Cloud Simulators

- OpenStack is no exception, and security issues are present in its lifecycle [9].

- Along with the OpenStack cloud, Ubuntu is available in a more advanced form [9].

- All cloud apps are compatible with OpenStack [9].

- Only a small number of resources are needed to experiment with OpenStack [9].

- Cloud simulators can be entirely changed and are completely open-source [9].

- Cloud simulators have unlimited support for testing [9].

- A simple desktop machine is sufficient to work on cloud simulators [9].

- Cloud simulators provide a graphical representation of results [9].

This paper consists of eight sections: The first section contains the introduction, and Section 2 is based on popular categories of cloud simulators for this research study. Related work regarding the research’s benefits and drawbacks is in Section 3. The research methodology and proposed work are described in Section 4. Section 5 is based on experimental results and findings that included a cloud simulator analysis, and Section 6 contains a discussion of this research study. Section 7 is based on the recommendations of real-world scenarios for the reader, and Section 8 concludes this study and makes recommendations for future work.

2. Highly Prominent and Extensible Categories of Cloud Simulators

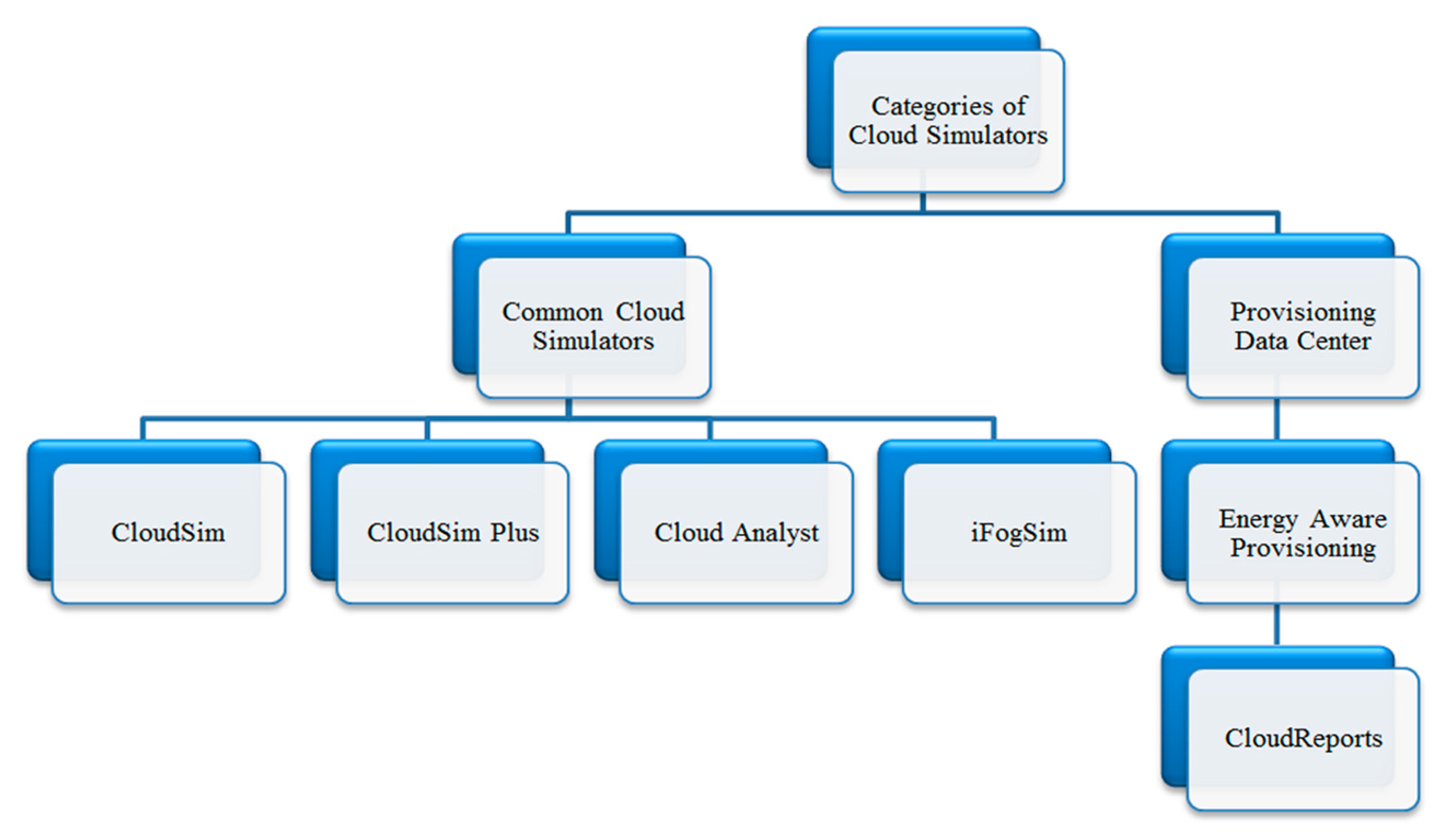

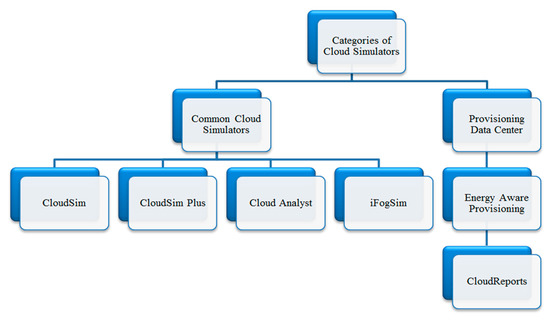

Cloud simulators are based on two popular categories: (A) common cloud simulators and (B) provisioning datacenters. Common cloud simulators include CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, and iFogSim. Provisioning DCs have energy-aware provisioning with a CloudReport simulator. Figure 1 demonstrates the popular categories of cloud simulators [10].

Figure 1.

Categories of cloud simulators [10].

2.1. Prominent Cloud Simulators

These tools are easy to expand and extremely versatile to use. Thereafter, only the characteristics that are of concern are expanded, while those contradictions are neglected. The resources that are described in this segment fall under this group [10].

2.1.1. CloudSim

According to Mansouri et al. [11], CloudSim is a toolkit for modeling CEs proposed by the CLOUD Laboratory, University of Melbourne, Australia. CloudSim models DCs, VMs, SBs, and resource methods to model provisioning. It provides a flexible transition between space-shared and time-shared resource allocations for processing components. Researchers can deploy cloud-based apps in a variety of environments with minimal effort and time spent evaluating the results. According to Sundas and Narayan Panda [12], CloudSim provides simulation, smooth modeling, and functional design within the context of the CC. It is a forum for the design of SBs, DCs, and large-scale allocation policies and scheduling. It has some extended features, such as a virtualization engine, to design the development and monitoring of the lifecycle of this system in the DC. The GridSim architecture developed in the lab for power systems serves as the foundation for CloudSim’s infrastructure. Puhan et al. [13] proposed IaaS (Service Infrastructure) layer modeling for cloud facilitation DCs that can be defined in CloudSim. With CloudSim, one can build various models to explain energy consumption in CEs. Users can simulate VM migration, host machine termination, and energy models. According to Hassaan [14], CloudSim’s simulation framework is a Java-based simulation toolkit that can design extremely large-scale clouds and support communication among cloud system components, as suggested. It is an event-focused simulator that has a unique feature known as a federated strategy. A federated cloud is a collection of internal and external cloud services that are distributed to meet business needs. Ismail [15] suggested that CloudSim is a virtualization and multi-tenant infrastructure simulation environment. CloudSim’s architecture was inspired by the limitations of true testbeds (such as Amazon EC2) in terms of scaling and replication of test results. As a result, CloudSim provides a generalized and extensible simulation framework that includes modeling, simulation, and testing aspects, which is especially useful for large-scale DCs in the cloud. It enables a cost-free, reproducible, and manageable environment and adjusts for success bottlenecks before deployment on real clouds.

2.1.2. CloudSim Plus

According to Filho et al. [16], CloudSim Plus is a Java 8 simulation system that allows various CC services to be modeled and simulated, ranging from IaaS to SaaS. It enables the introduction of simulation scenarios for the research, evaluation, and validation of algorithms for a variety of purposes. CloudSim Plus is an open-source simulation framework that aims to provide a tool that is extendable, modular, and accurate by adhering to software engineering principles and an object-oriented architecture. According to Naik and Mehta [7], CloudSim Plus, an object-oriented simulation application that is an extension of CloudSim, was proposed as free software. The CloudSim Plus API is the main component representing the simulation system API and the use of cloud simulation experiments must be permitted according to the API. According to Markus and Kertesz [17], CloudSim Plus is a redesigned and rebranded version of CloudSim that aims to make simulation easier to use and more accurate. Additionally, it is available on GitHub.

2.1.3. CloudAnalyst

Anusooya et al. [18] reported that the CloudAnalyst simulation tool compares the output of different algorithms to the total response time. The CloudAnalyst tool looks uncomplicated, as it has a graphical environment that seems easy to apply. The visual outcome allows users to interpret findings more efficiently and readily. CloudAnalyst features include: (1) Being easy to apply; (2) defining simulation features with wide configuration points and flexibility; (3) generating results based on graphics; (4) allowing for experiment repetitions; and (5) having the capacity to store the output. Nandhini and Gnanasekaran [19] listed CloudAnalyst features such as: (1) Integrating cloud application analytics units into CloudSim; (2) geographically dispersing computer servers and client workloads for assessment using simulation in a large-scale cloud framework; (3) SBs maximizing the efficiency of software and service suppliers; and (4) the main units being composed of the datacenter, server, server broker, host, VM, and cloud coordinator. Desyatirikova and Khodar [20] indicated that CloudAnalyst would include a collection of elements that will provide the basis for CC, such as VMs, Cloudlets (Jobs and User Requests), DCs, SBs, and Hosts.

2.1.4. iFogSim

Bala and Chishti [21] suggest that iFogSim is a popular fog computing simulator. iFogSim has been established, and all CloudSim elements and features have been incorporated into iFogSim. The research community has overwhelmingly supported iFogSim, which can identify various performance parameters such as energy consumption, latency, response time, cost, and so on. It also allows for the replication of research in a stable environment. It employs a stream processing model in which sensors continuously generate data that fog devices evaluate, allowing users to quickly compare the results of various placement algorithms. Seo [22] suggested that iFogSim is one of the most popular CloudSim simulators. iFogSim can model IoT and fog conditions to calculate latency, network congestion, and device energy consumption. However, a simplified approach to modeling latency workloads is used. iFogSim will simulate a three-layer IoT fog system in various configurations. Although the simulator is used to test a variety of workloads, it fails in three-layer IoT fog systems because it fails to accurately model the computation schedule when processing items. It is well known that multi-core CPU efficiency interactions between device components do not expand sequentially. Markus and Kertesz [17] indicated that there are also more advanced iFogSim extensions. MyiFogSim (available on GitHub) helps mobile users handle VM migration. A key feature is the ability to replicate user mobility and its relationship to the VM migration policy. The iFogSimWithDataPlacement tool (available on GitHub) is another extension that proposes a method for data management studies into how data is stored in a fog system. For data location, it also analyzes latency, network utilization, and energy expenditure. Unfortunately, many simulators (such as Fog-Torch, OPNET, or SpanEdge) are designed to represent a single aspect of computing, making them less productive for general simulations.

2.2. Energy-Aware Provisioning

For the supplier, the energy supply is the most important because it can produce substantial savings. Initially, energy efficiency can be achieved both at the level of the network devices and at the level of the host. The normal parameter for estimating energy usage is primarily the processor fee. As this aspect is a significant contributor to the energy bill, more advanced simulators provide savings because they concentrate on modeling energy usage [10].

CloudReports

Zaidi [8] reported that CloudReports are a powerful and flexible simulation tool for computing DCs and resource energy using a GUI in a CC environment; with high-level data, it produces reports and organizes simulation results. The central enterprises of CloudReports are composed of clients, DCs, physical computers, VMs, network and network area space, and so on. These organizations work to run a simulation environment with the simulation administrator. Fairouz Fakhfakh et al. [23] proposed several changes to the top of the architecture of CloudSim. The proposal introduces a GUI that offers several features. First, it enables the simultaneous running of several simulations. With detailed information and the ability to export simulation data, it can produce reports. This data is linked to the usage costs of services, energy usage, ET, and so on.

Table 1 lists all of the key questions associated with the review’s subtopics, while Table 2 [24] shows the clear benefits and drawbacks of the reviewed simulators. Table 3 summarizes the key models of cloud simulation presented in this section I-A (CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports) for various parameters such as simulator type, simulation time, availability, hardware/software associated, programming language, basic policy, repetition of analysis, GUI, user expectations, and dynamic run. The energy-consuming parameters in the selected cloud simulators are listed in Table 4 [15].

Table 1.

A list of key questions.

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of cloud simulators [16,16,25,26,27,28].

Table 3.

Selection of cloud simulators: a simulation-based assessment of the specifications [26,29,31,32,33].

Table 4.

The following is a list of the energy-consuming parameters found in the selected cloud simulators [11,15,26,31].

3. Related Work

There has been a lot of research conducted on cloud simulation tools for CC. This review focuses on CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports. Table 5 summarizes the literature review, and Table 6 shows a comparative analysis of the literature review based on various factors.

According to Bahwaireth et al. [1], CloudSim, CloudAnalyst, CloudReports, CloudExp, GreenCloud, and iCanCloud are among the most effective simulation tools in the field of research. Some of these instruments are used to conduct experiments that demonstrate the cloud simulator’s capabilities. According to Mishra et al. [2], the simulation is carried out in the CloudSim simulator to analyze the performance of heuristic-based algorithms, and the results are presented. Rashid and Chaturvedi [3] tried to explore different CC services, apps, and features in this paper and provide unique examples of cloud services provided by the most popular cloud services, such as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon, with models of CC services and advantages. According to Prajapati and Sariya [4], load changes are spread across multiple hubs to ensure that no single hub is overburdened, which assists in the legitimate use of properties and also enhances the framework’s execution. Many current calculations offer stack changes and better use of properties. Bambrik [10] proposed that a detailed survey of the current CC simulators be undertaken to explore the characteristics, software design, and ingenuity behind these frameworks.

According to Motlhabane et al. [24], several cloud simulators have been developed over the years as cost-effective ways of performing cloud research tasks. Based on different measures, the authors conducted a comparative analysis of thirteen cloud simulators. Given the cloud simulator’s design, strengths, shortcomings, and recommendations, the aim was to provide insights into each of them to direct researchers on the choice of suitable instruments. T. Lucia Agnes Beena and Lawanya [34] introduced numerous cloud simulators that have been developed over the years to perform cloud testing tasks in an energy-efficient way. Almost ten cloud simulators based on energy-efficient parameters were evaluated in their paper, and a report was presented. Suryateja [35] suggested that different cloud simulators, which have been developed over the years, are a cost-effective way of performing tasks in cloud research. The paper compares cloud simulators based on different parameters and presents the findings and explanations that enable new researchers to select an acceptable cloud simulator. Khurana and Bawa [36] proposed that the quality metrics of cloud simulators be discussed and that the quality indicators addressed by them be integrated into each simulator. In the end, the authors conclude that there is a need to build a simulator that addresses acceptable quality metrics.

Sajjad et al. [37] suggested a comparative assessment of the most popular state-of-the-art energy-conscious cloud simulators, such as GreenCloud, CloudSim, iCanCloud, CloudAnalyst, NetworkCloudSim, and CloudReports. Khalil et al. [26] suggested that the common architecture of cloud simulators should be addressed and that cloud simulators should be evaluated based on various parameters. The outcomes were discussed and illustrated the various capabilities, problem suitability, and extensibility of the cloud simulators studied. Sumitha J. and Priya [38] proposed that CC has the principles of DCs, which are distributed or dispersed worldwide with single or multiple DCs, and virtualization over the internet with on-demand services. Shakir and Razzaque [39] suggested that a simulation be carried out using the CloudAnalyst framework to see the contrast of results between them. Among the frameworks being compared, the round-robin is the best.

Vashistha and Sholliya [40] suggested the availability of many open-source simulators for CC, such as CloudSim, CloudAnalyst, GreenCloud, iCanCloud, EMUSIM, GroudSim, and DCSim environments, and noted that a few principles of CC cannot be satisfactorily simulated by any of these simulators. Kumar et al. [41] conducted a basic and similar investigation of the current simulation tools in distributed computing. Based on the results of this study, further inquiries began to emerge. Malhotra [42] conducted a comparative analysis of current cloud simulators with the aim of helping end-users select the appropriate simulator. Maarouf et al. [43] investigated the different CC simulation platforms and tools and identified their strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, the paper notes the challenges and future directions for research. Pagare and Koli [44] propose an expandable simulation system called CloudSim that supports simulation, CC modeling, the development of one or more VMs on a simulated DC node, jobs, and the mapping to appropriate VMs, service management capacity, and cloud infrastructure modeling. CloudSim can also manage cloud storage mechanisms and enable the simulation of several DCs.

Gupta and Beri [45] suggested that the conceptual cost of purchasing the services of different providers could lead to an increase in money and time budgets or wastage. The solution to this problem is to test out the numerous simulation tools that are available on the market. The article lists some of the simulation methods used for simulation and modeling purposes. Asir Antony Singh et al. [46] proposed using simulation methods to test CC performance before building the cloud. They used CloudSim as a platform for modeling and simulating the CC world. Andrade and Nogueira [47] proposed the Stochastic Petri Net (SPN) approach to evaluate cloud-based DR solutions for IT environments. This approach enables different performance metrics to be evaluated (e.g., response time, throughput, availability, and others) and can therefore assist DR coordinators in choosing the most suitable DR solution and also validate the analytical approach’s accuracy by comparing analytical results with those obtained from the CloudSim Plus cloud simulator. Dogra and Singh [27] demonstrate the capabilities of the three well-known cloud simulators: (a) CloudSim, (b) CloudAnalyst, and (c) CloudReport. As with other cloud simulations, the difference is predicated on capacity and flexibility, as well as nearly identical systems and functionalities. These cloud simulators are software-based simulation tools that are assessed to determine their capabilities depending on a variety of parameters. An experimental evaluation of this equipment has been performed to determine the optimal method for cloud simulation. Ahmed and Zaman [48] reported that CloudSim Plus has a new, up-to-date, fully-featured, and fully-recorded simulation structure. CC infrastructure and application services are easy to use and develop, allowing for modeling, simulation, and experimentation. This enables developers to concentrate on particular system design problems to be explored without taking into consideration the low-level knowledge relevant to cloud-based infrastructures and services.

Gupta et al. [29] proposed iFogSim as an API based on the jJava programming language that inherits CloudSim’s existing API to handle its underlying discrete event-based simulation and for effective network-related workload handling. Researchers can first understand the project structure using CloudSim’s API before implementing it in iFogSim. Jena et al. [31] suggested the basic differences between cloud-based simulators in this research paper: CloudSim, CloudAnalyst, CloudReports, CloudSched, and GreenCloud. Based on the following parameters, such as extension, correlation, and classification, researchers carried out an extensive investigation with different groups and also took some of the essential open-source cloud resources for comparative analysis for better utility. Esparcia and Singh [32] suggested comprehensively exploring cloud simulation tools. Specifically, because each simulator has its own purpose, it is to suggest which simulator can fit one’s preferences. The four traditional and modern tools for modeling and studying the true cloud were discussed, and the simulation models, features, and simulation results of each of the simulation tools were also identified. Ashalatha R. et al. [33] described the popular simulation tools for large CEs that take care of computing resources and user workloads. Depending on the specifications, a variety of simulators can perform different simulations in the CE. Bhatia and Sharma [49] conducted a critical study and analysis of the different simulators available in the computer world for CC. The analysis will serve as an excellent source of reference for cloud simulators that might be required by researchers and academics. Results show that CloudSim is the core of many simulation algorithms for CC and is commonly used by most researchers. Simulators can perform different simulations in the CE. Shahid et al. [50] proposed that existing load-balancing techniques also explore the challenges of LB in the CC environment and identify the necessity for a novel load-balancing algorithm that uses FT metrics. Shahid et al. [51] proposed that the major goal of LB is to efficiently control load across numerous cloud nodes such that a node is under or overloaded. LB can help save time and money and improve the performance of a system by optimizing the entire system’s performance. Najat Tissir et al. [9] investigated the current state of the components, subcomponents, and interactions with OpenStack. The examination of the most prevalent OpenStack vulnerabilities is therefore the focus of their study based on ten years’ worth of security reports analysis. Alberto Nunez et al. [52] suggested using Cloud Expert, an intelligent system built on metamorphic testing that chooses the best simulator to cover the user’s desired characteristics and also analyzes the fundamental characteristics of some well-known cloud simulators to produce metamorphic rules that are then used to represent the simulator’s qualities. Harvinder Singh et al. [53] suggested that six cloud simulators be examined to develop and test various cloud apps. The study discusses various cloud simulators and contrasts them based on many factors, such as programming languages, support for availability and SLAs, and so forth. Youssef Saadi and Said El Kafhali [54] proposed an energy-efficient strategy (EES) for VM consolidation in a CE to lower energy consumption and increase job throughput. The performance-to-power ratio is used in the proposal to establish upper criteria for overload detection. Additionally, EES takes into account the total workload usage in the DC when establishing lower criteria, which can reduce the number of VM migrations. Daniel G. Lago et al. [55] suggested the use of SinergyCloud to assess DCs in hybrid clouds with a precise level of abstraction that enables the evaluation of various cloud situations, such as energy consumption, workflow makespan, the complete duration of tasks, and VM migrations. The simulation of hybrid clouds with numerous DCs and millions of devices is possible with SinergyCloud. It also has a less challenging learning curve than other simulators because it is a Java-based, event-driven, and packet-level simulator.

Table 5.

The summary of the related work.

Table 5.

The summary of the related work.

| Ref | Name | Year | Simulator | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Khadijah Bahwaireth et al. | 2016 |

|

|

|

| [2] | Sambit Kumar Mishra et al. | 2018 | CloudSim |

| Not assessing the suggested algorithms for cloud deployment in the real world. |

| [3] | Aaqib Rashid and Amit Chaturvedi | 2019 | CloudSim | With a broad range of apps, it offers cost-effective services. |

|

| [4] | Priyanka Prajapati and Amit Kumar Sariya | 2019 | CloudAnalyst | Provides flexibility, better use of assets, and better response times. |

|

| [10] | Ilyas Bambrik | 2020 |

|

|

|

| [11] | N. Mansouri et al. | 2020 |

|

|

|

| [12] | Amit Sundas and Surya Narayan Panda | 2020 | CloudSim | Provides simulation capability for performing several duplications at the same interval. |

|

| [13] | Sharmistha Puhan et al. | 2020 |

|

| With fewer machines, the DC does not have an improved response time, and higher energy is consumed for higher-frequency memory configurations. |

| [14] | Muhammad Hassaan | 2020 |

|

|

|

| [15] | Azlan Ismail | 2020 |

|

|

|

| [16] | Manoel C. Silva Filho et al. | 2017 | CloudSim Plus |

|

|

| [7] | Niti Naik and Mayuri A. Mehta | 2018 |

| Provides a catalog of cloud simulators available to assist researchers and developers in choosing the most suitable method for cloud simulation. |

|

| [17] | Andras Markus and Attila Kertesz | 2020 | iFogSim |

|

|

| [18] | G. Anusooya et al. | 2020 | CloudSim | It offers cloud energy, power savings, and DC workload management. | Lack of consistency and performance in simulation. |

| [19] | J.M.Nandhini and T.Gnanasekaran | 2019 | CloudSim | Help in measuring costs and the use of assets. | Insufficient storage problems and VM failures with variable ability. |

| [20] | Elena N. Desyatirikova and Almothana Khodar | 2019 | CloudAnalyst |

|

|

| [21] | Mohammad Irfan Bala and Mohammad Ahsan Chishti | 2020 | iFogSim | By distributing the application modules between fog devices and cloud DCs, efficient utilization of the Cloud-Fog resources is achieved. | There is a need for further improvements in algorithms for LB. |

| [22] | Dongjoo Seo et al. | 2020 | iFogSim | In this framework, the controller module is integrated. |

|

| [8] | Taskeen Zaidi | 2020 | CloudReports |

|

|

| [23] | Fairouz Fakhfakh et al. | 2017 |

|

|

|

| [24] | Neo Motlhabane et al. | 2018 |

|

|

|

| [34] | T. Lucia Agnes Beena and J. Jenifer Lawanya | 2018 |

|

| There is no GUI in CloudSim. |

| [35] | Pericherla S Suryateja | 2016 |

|

|

|

| [36] | Ravi Khurana and Rajesh Kumar Bawa | 2016 | CloudSim |

|

|

| [25] | James Byrne et al. | 2017 |

|

|

|

| [37] | Ammara Sajjad et al. | 2018 |

|

|

|

| [26] | Khaled M. Khalil et al. | 2017 |

| CloudSim and CloudAnalyst are cost-effective simulators. |

|

| [56] | Soumya Ranjan Jena et al. | 2020 | CloudAnalyst | In comparison to the other two models, Space-Shared and Dynamic-Workload, it uses fewer resources (CPU, RAM, and bandwidth). |

|

| [38] | Sumitha. J, and S.Manju Priya | 2018 |

|

|

|

| [39] | Muhammad Sohaib Shakir, and Abdul Razzaque | 2017 | CloudAnalyst |

|

|

| [40] | Avneesh Vashistha and Shourabh Sholliya | 2017 | CloudAnalyst |

|

|

| [41] | K. Arun Kumar et al. | 2017 | CloudReports |

|

|

| [42] | Manisha Malhotra | 2017 |

|

| The resource provisioning mechanisms in CloudSim are limited, and it lacks a GUI. |

| [43] | Adil Maarouf et al. | 2015 | CloudSim | The transition between space-shared and time-shared assignment of processing cores to virtualized services provides great versatility. |

|

| [44] | Jayshri Damodar Pagare and Nitin A Koli | 2015 | CloudSim |

|

|

| [45] | Kiran Gupta and Rydhm Beri | 2016 | CloudSim |

|

|

| [46] | Asir Antony Gnana Singh et al. | 2018 | CloudSim | Get the system’s ET under different CC organizations. | Lack of performance. |

| [47] | Ermeson Andrade and Bruno Nogueira | 2018 | CloudSim Plus |

|

|

| [27] | Shobhna Dogra and A.J Singh | 2020 |

|

|

|

| [16] | Manoelcampos | 2020 | CloudSim Plus |

| Specific system design. |

| [29] | Harshit Gupta | 2017 |

|

| Lack of inadequate infrastructure. |

| [28] | David Abreu Perez et al. | 2019 | iFogSim | Best ET. |

|

| [31] | Soumya Ranjan Jena et al. | 2020 |

|

| None of them is suitable for all experiences and agreements. |

| [32] | Jay Ar P. Esparcia and Monisha Singh | 2017 | CloudAnalyst | Extensible, scalable, versatile, fast, open-source, user-friendly, and result-oriented resources are available. |

|

| [33] | Ashalatha R. et al. | 2016 |

|

| The simulation framework does not provide a federated CE. |

| [49] | Mandeep S. Bhatia and Manmohan Sharma | 2016 |

|

| Selecting one over many others is a tough job. |

| [50] | Muhammad Asim Shahid et al. | 2020 | CloudAnalyst | Meet the deadline for the makespan. | Unable to predict when the burst will occur. |

| [51] | Muhammad Asim Shahid et al. | 2021 | CloudSim | FT is a feature of load-balancing algorithms, which means the researchers can provide standardized LB despite arbitrary node or connection errors. | Lack of availability of key resources, as well as the installation of apps, is a concern. |

| [9] | Najat Tissir et al. | 2020 | OpenStack | Identify the tendencies associated with its vulnerability. | It can fail due to security issues. |

| [52] | Alberto Nunez et al. | 2022 | Cloud Expert |

| Lack of graphical representation of results. |

| [53] | Harvinder Singh et al. | 2021 |

| They provided effective simulators. | Lack of providing a view of all simulators. |

| [54] | Youssef Saadi and Said El Kafhali | 2020 | Energy-Efficient Simulator |

| Lack of real-time CE for variable factors. |

| [55] | Daniel G. Lago et al. | 2021 | SinergyCloud |

|

|

Table 6.

A comparative analysis of the literature review based on various factors.

Table 6.

A comparative analysis of the literature review based on various factors.

| Ref | Data Storage | QOS | Cost- Effectiveness | Network Model | Security | SLA | GUI | Flexibility | Availability | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [2] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [3] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [4] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [10] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [11] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [12] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [14] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [15] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [16] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [7] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [17] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [18] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [20] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [21] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [8] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [23] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [24] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [34] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [35] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [36] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [37] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [26] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [56] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [38] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [39] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [40] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [41] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [42] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [43] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [44] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| [45] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [46] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [48] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [29] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [28] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [32] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [33] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [49] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [51] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

4. Problem Statement

Because it is difficult to test new mechanisms in a real cloud computing environment and because researchers frequently cannot access a real cloud computing environment, using a simulation to model the mechanism and evaluate the results is required. Simulating a data center saves time and effort spent configuring a real testing environment.

5. Research Methodology

This section focuses on the cloud simulator architectures and proposes a selection strategy for the simulator based on research gaps. The architecture of the cloud simulators is incorporated and explained.

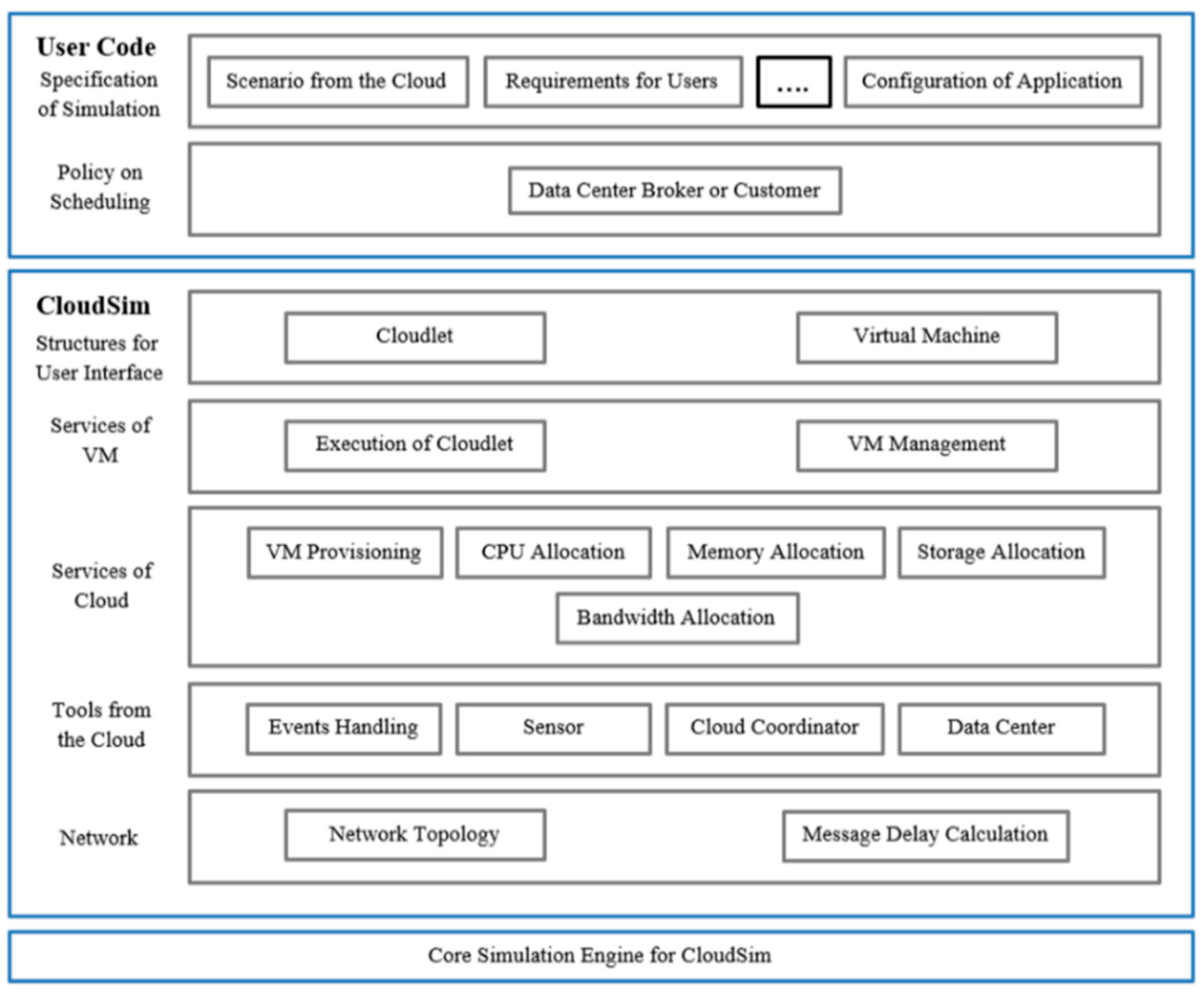

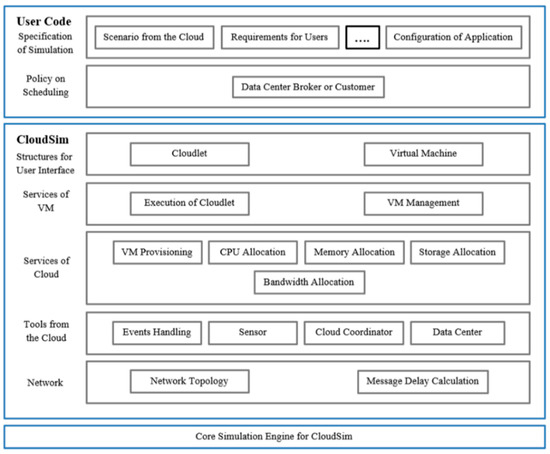

5.1. CloudSim Architecture

CloudSim was proposed in 2009 [43]. Figure 2 depicts the multifaceted software system scheme and structural components of CloudSim. The CloudSim simulation layer allows for the creation and simulation of virtualized cloud-based [24] and DC [38] environments with clear organizational boundaries for VMs, memory, storage, and bandwidth. This layer’s critical issues include, for example, assigning hosts to VMs, controlling request execution, and observing robust method states. The layer cost for memory and space use is reasonable [24]. There is no GUI [40], and it has a small prototype declaration that does not fund TCP/IP [24]. The CloudSim layer handled the initialization and operation of main identities (VMs, hosts, DCs, and apps) during the simulation test [44]. Many library functions written in the Java programming language are included in CloudSim [46].

Figure 2.

The architecture of CloudSim [34,42].

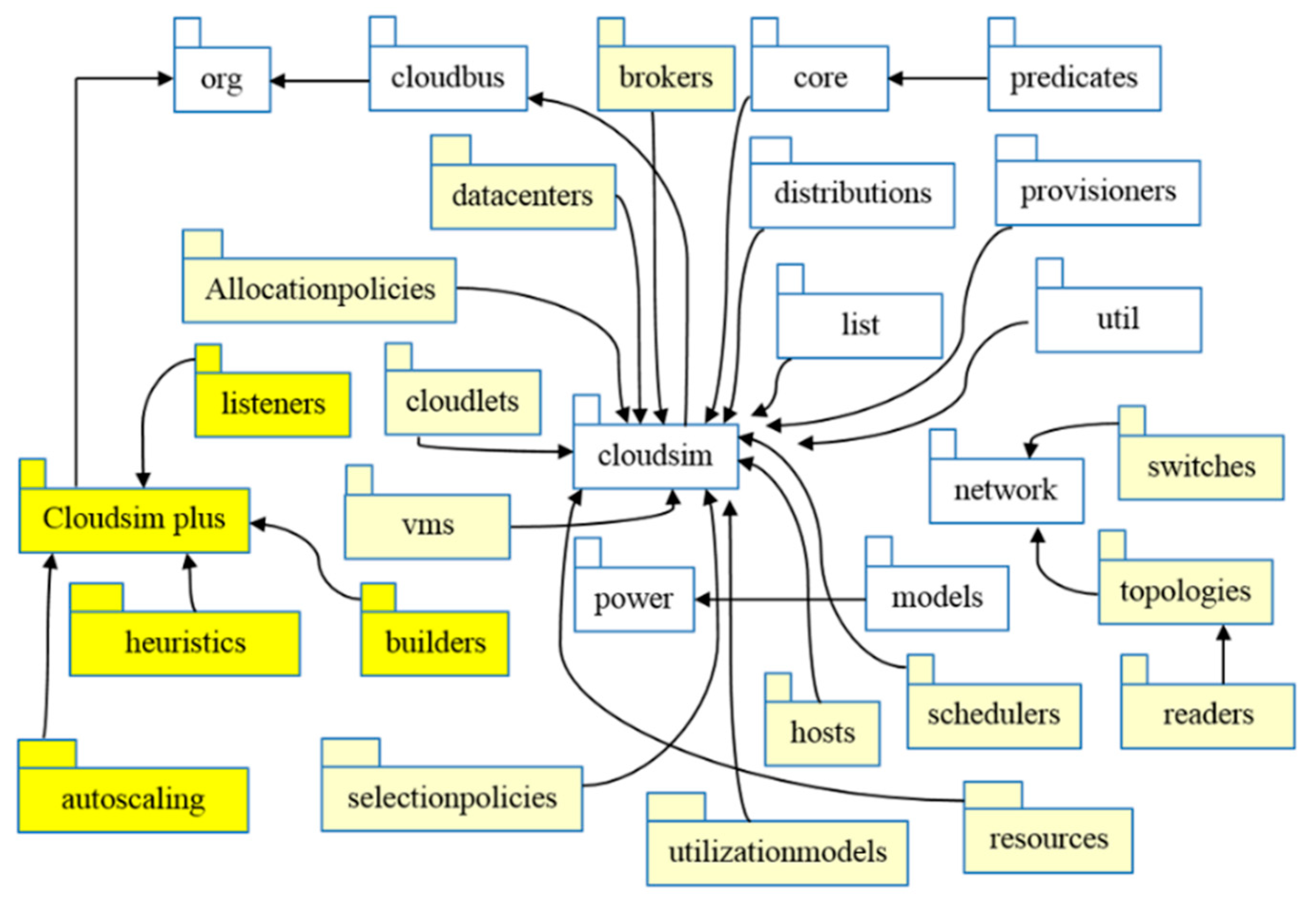

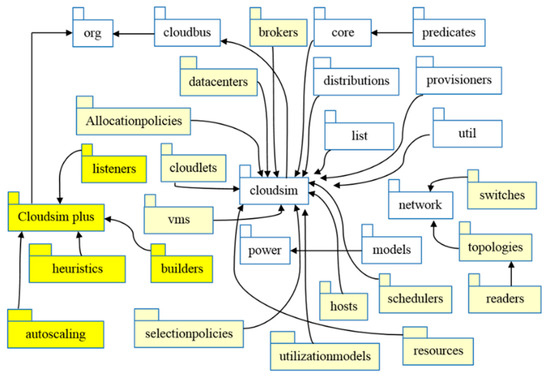

5.2. CloudSim Plus Architecture

CloudSim Plus is a mix of various components. The principal component representing the simulation system API is the CloudSim Plus API. It is the single module needed to allow cloud simulation experiments to be implemented [16]. For the modeling and simulation of CC infrastructures and facilities, CloudSim Plus is an extensible simulation platform [47]. A condensed overview of its package structure is shown in Figure 3. Packages with a darker color include CloudSim Plus’s unique functionality. The most important CloudSim Plus bundles and classes are listed below [16]:

Figure 3.

CloudSim Plus API package kit [16].

- Distributions: Groups that produce pseudo-random numbers after many statistical distributions that are also used by the simulation API and the developers creating the simulations [16].

- Network: Classes for building internet infrastructure for data centers that enable network simulations [16].

- Power: Groups that allow power-aware simulations, namely models of energy usage that developer can expand in the simulations [16].

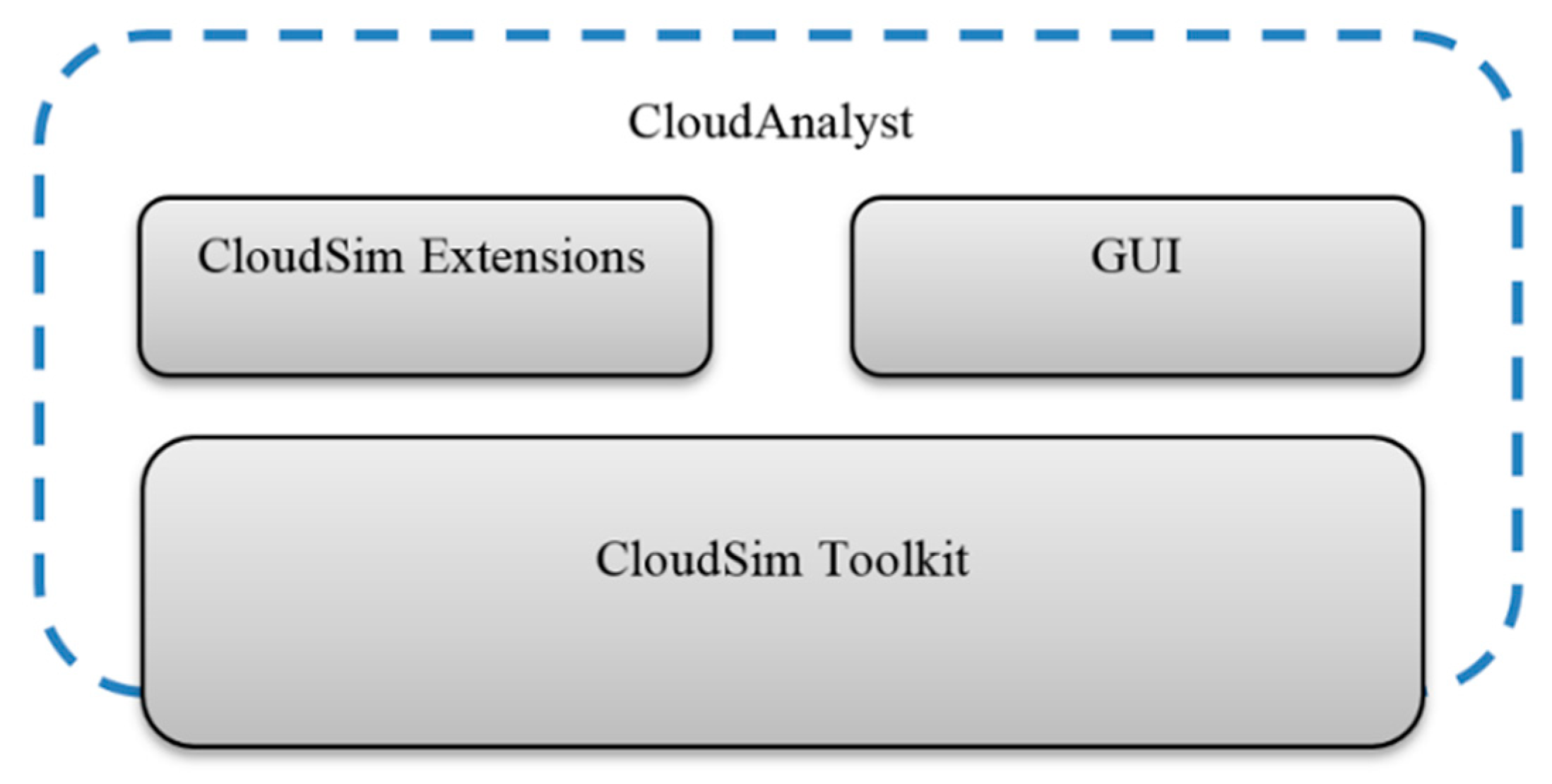

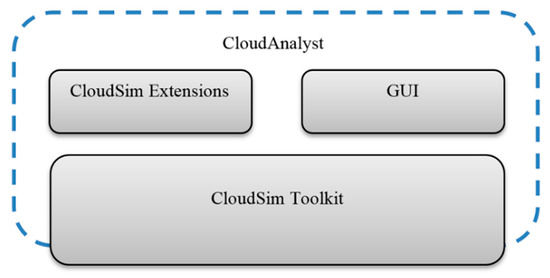

5.3. CloudAnalyst Architecture

The CloudAnalyst architecture is shown in Figure 4. CloudAnalyst offers an [35] easy-to-use GUI [39] to manage any geographically dispersed device, such as application workload definition, user location information, creating traffic, DC location, number of customers per DC, and number of DC resources. In the form of a map or table, CloudAnalyst may produce output that summarizes the massive number of users and device states during the simulation period [35]. It distinguishes between the environment for programming and the environment for simulation [45].

Figure 4.

CloudAnalyst architecture [25,36].

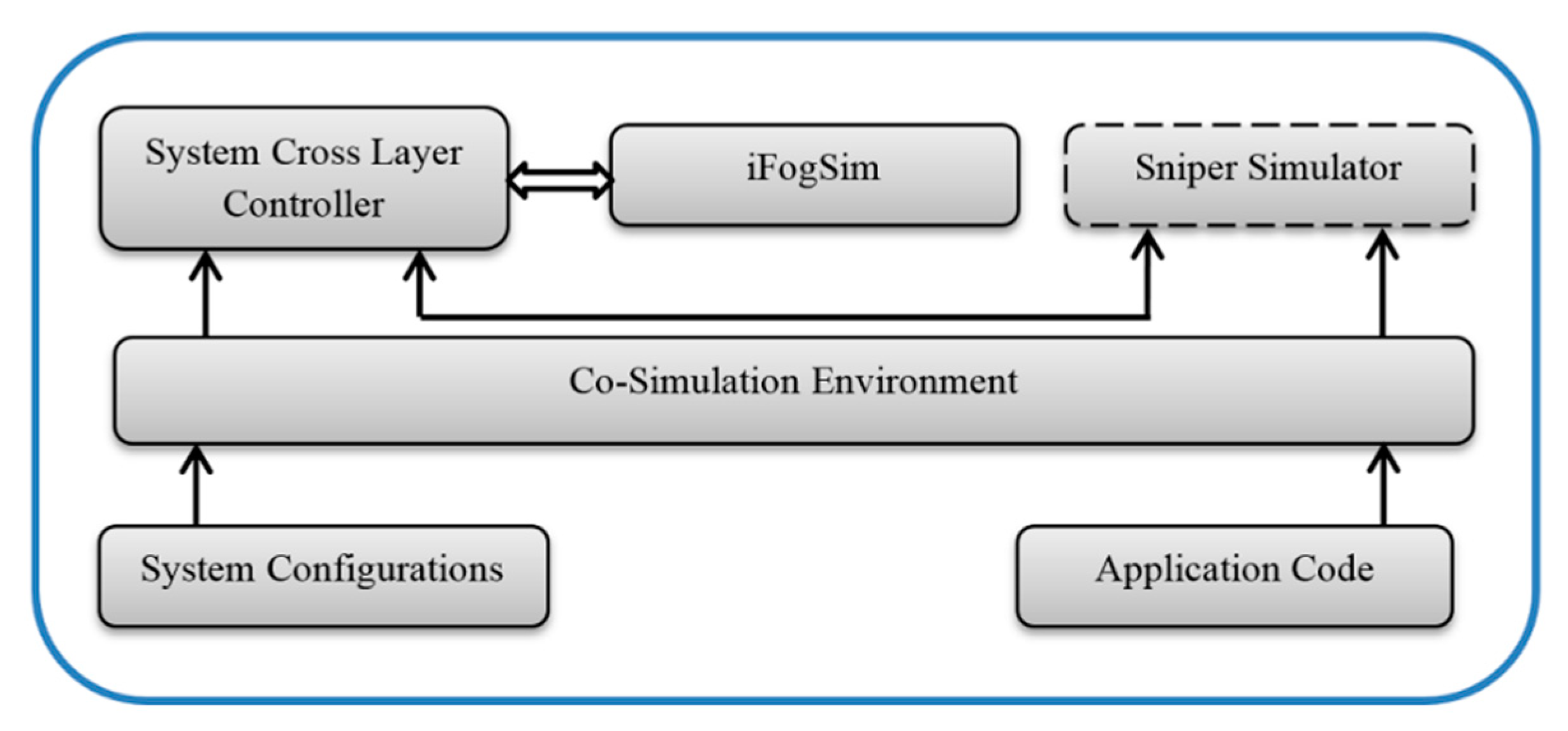

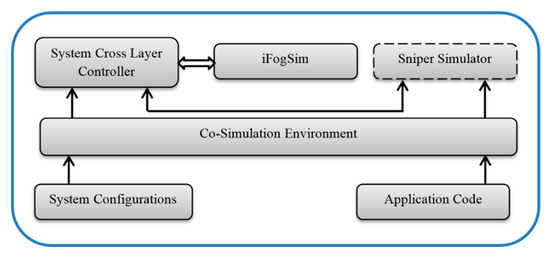

5.4. iFogSim Architecture

The iFogSim framework contains numerous components: (1) the iFogSim simulator expanded; (2) a Sniper Multi-Core simulator; (3) a System Cross-layer Controller; and (4) an Environment co-simulation module (see Figure 5). The Simulation Module Co-simulation Environment starts the simulation by configuring the loading device and application codes. Machine settings include hardware requirements for the virtual computer, the network layer, and the simulation framework. Program codes are the target programs that should be run on VMs. To begin with, the Sniper simulator runs the loaded app code on the specified system hardware configuration to generate statistics for subsequent moves. iFogSim uses the generated statistics to simulate the device and network layers based on the device specifications. The framework logs the ET and energy consumption of the application for the specified device configuration [22].

Figure 5.

iFogSim architecture [22].

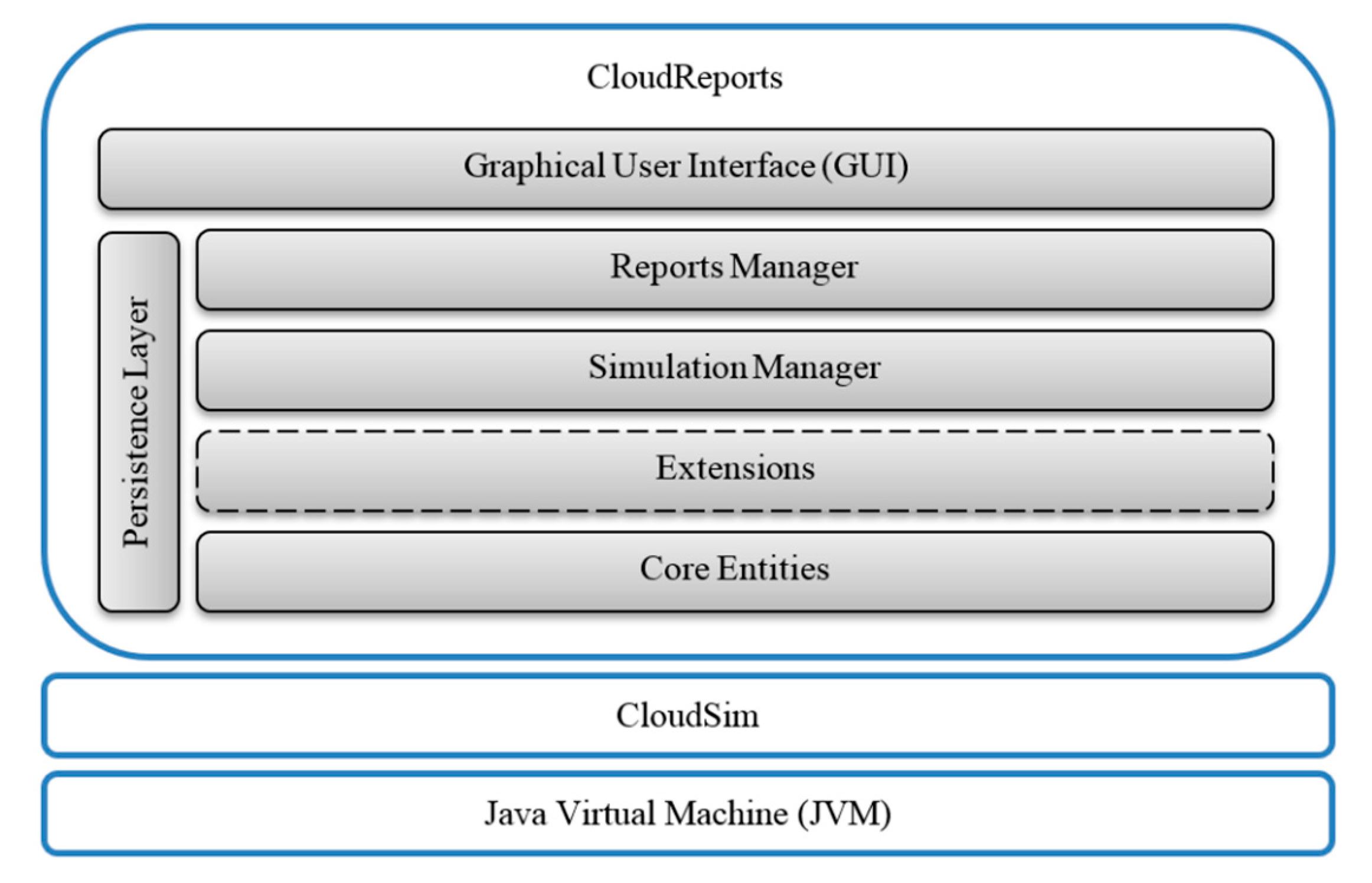

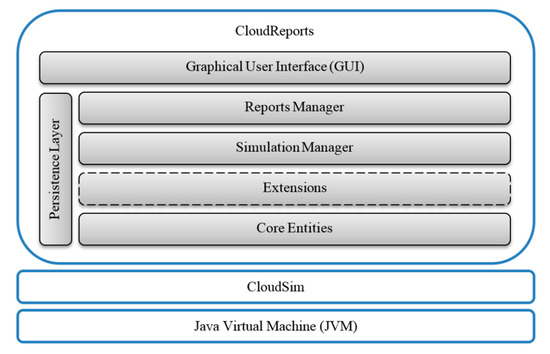

5.5. CloudReports Architecture

The CloudReports architecture is shown in Figure 6. It is an expandable simulation software for energy-aware CC environments that enables researchers to design several complicated concepts through an interface. On top of the [37] CloudSim simulation engine [56], it offers four layers: (1) Report manager; (2) Simulation manager; (3) Extensions; and (4) Core entities. The key benefit of CloudReports is its modular architecture, which enables its API to be expanded to experiment with new algorithms for scheduling and provisioning [25]. CloudReports supports modeling for restricted [37] power consumption [57] and is based on the mechanism of event-oriented simulation. CloudReports’ important features involve high accuracy and adaptive simulations based on help for auto-VM migration. It provides the Java Reflection API to build plug-in extensions [37]. It provides a GUI that offers unique characteristics [41]. Table 7 summarizes the various cloud simulator architectures.

Figure 6.

CloudReports architecture [1].

Table 7.

A summary of various cloud simulator architectures [1,16,22,35,49].

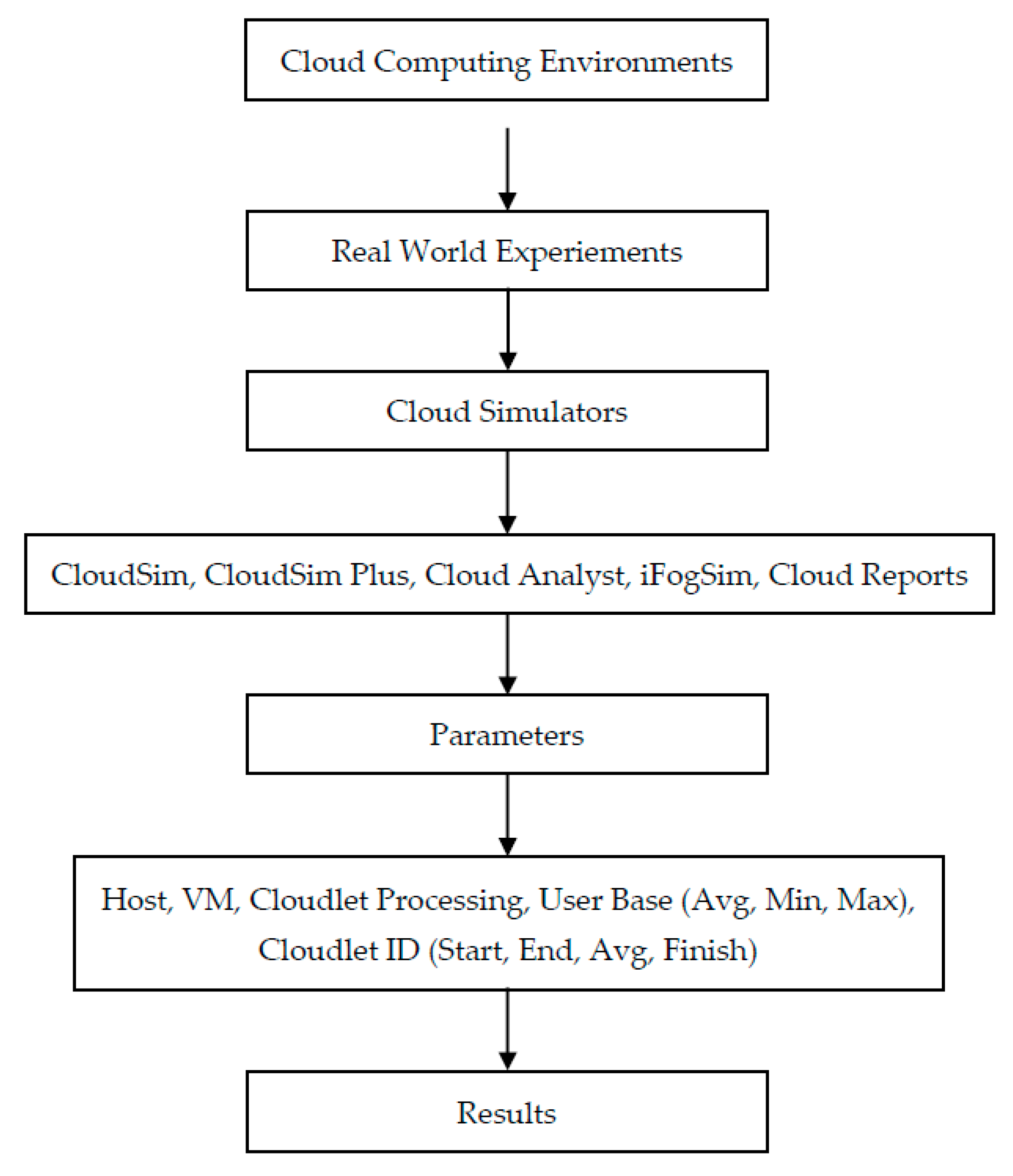

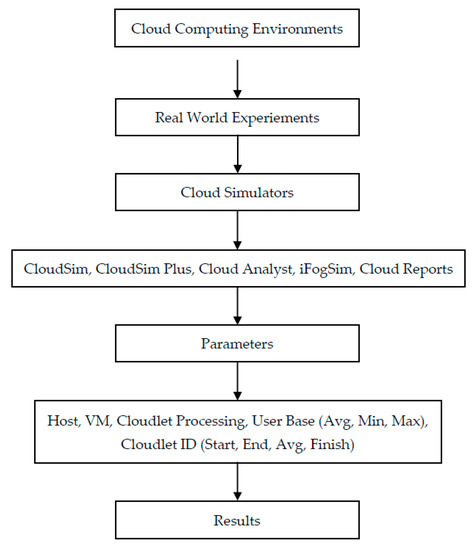

5.6. Proposed Work with Selection Strategy for the Simulator Based on Research Gaps

Based on an extensive literature review, it has been found that most researchers have not considered experiments in a real environment, hence the need for a systematic analysis of cloud simulation tools.

This section proposes to evaluate cloud simulators for public clouds in particular. Only parameters that can be measured by the cloud client are used in the simulator’s configuration: inbound and outbound HPEs, VM PEs, cloudlet PEs, UB, and cloudlet ET parameters.

Various simulators and experiments were carried out in this study, which may have an impact on future cloud simulation work. The selected cloud simulators highlight the related succeeding works in Section 6 below. The following works are primarily based on the following parameters: HPEs, VM PEs, Cloudlet PEs, Avg, Min, Max, and Cloudlet ET. This research paper discusses popular simulators for experimental campaigns and successful work analysis. Based on this research and to the best of our knowledge, no successful work has been associated with other simulators. Figure 7 shows the framework for analysis and comparison.

Figure 7.

Framework for analysis and comparison.

6. Experimental Results and Findings

In this section, the paper’s contribution will be compared with the state-of-the-art simulators currently used in CC. With a focus on the increasing popularity of CC, the experiments of cloud simulators are added, and researchers in this field need to perform real experiments in the cloud simulator studies. It is expensive to configure and run these tests in actual CEs. Modeling and simulation methods, however, are sufficient solutions for these and also provide excellent alternatives for emulating environments in CC.

Throughout this section, Section 6.1–Section 6.5 are used for source code and to evaluate the performance of changed CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports exploiting the power usage of hosts and VMs, the usage of the round-robin VM allocation policy, the process flow of the DC using a closet DC SB technique, and the round-robin DC broker policy with host and VM power consumption to capture a more realistic scenario where performance may change due to the power usage of hosts and VMs.

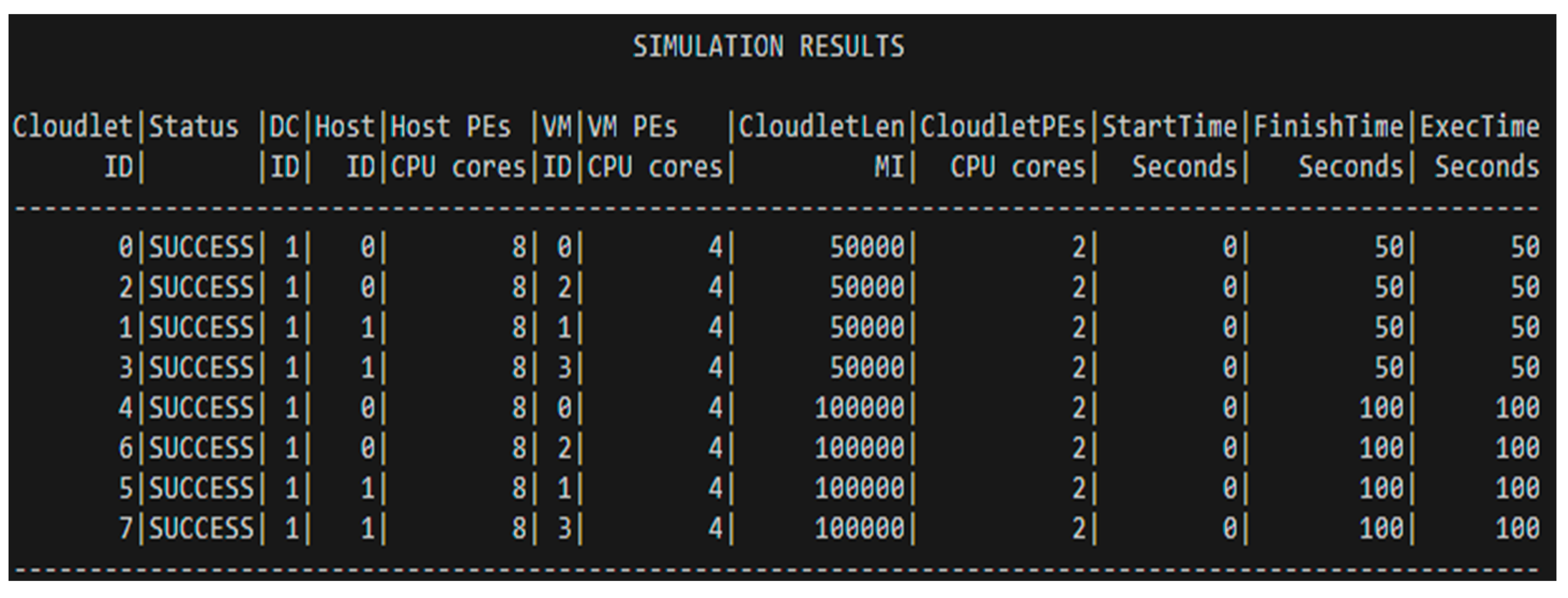

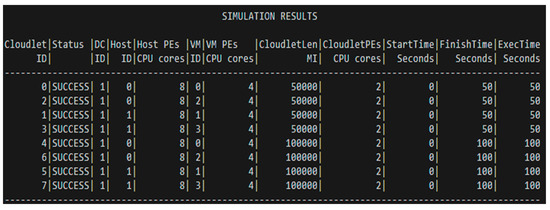

6.1. CloudSim

The following scenario evaluates CloudSim’s modeling and simulation capabilities. The goal of this scenario is to figure out the power usage of hosts and VMs. The simulation environment is composed of Scheduling Interval 10, Hosts 2, Hosts PEs (PEs) 8, VMs 4, VMs PEs 4, Cloudlets 8, Cloudlets PEs 2, and cloudlet length 50,000 for implementation purposes.

As per FCFS’s default policy, each VM is assigned to the first available host with available PEs. Each host distributes/shares its core capacity dynamically among all VMs running on the same time-shared VM scheduler (Pes). CloudSim’s modeling and simulation capabilities are depicted in Figure 8. Figure 8 shows that VMs are executing successfully according to the parameters that were given at the time of creation. This means that CloudSim is the best simulator for the power usage of hosts and VMs.

Figure 8.

Simulation results of CloudSim based on the power usage of hosts and VMs.

6.2. CloudSim Plus

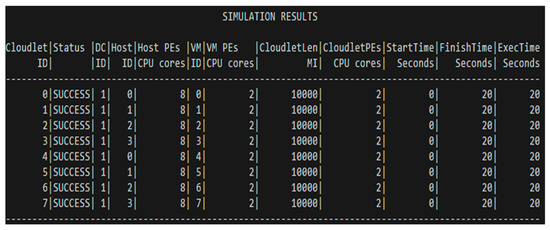

The following scenario was built to test the modeling and simulation capabilities of CloudSim Plus and determine the use of the round-robin VM allocation policy. The simulation environment is composed of Hosts 4, Hosts PEs 8, VMs 8, VMs PEs 2, Cloudlets 8, Cloudlets PEs 2, and cloudlet length 10,000.

In this manner, it loads a VM onto a host and proceeds to the next host. Not all hosts are turned on when they are created. When VMs are added, hosts are activated on demand, as evidenced by logs. Remember that such a policy is extremely naive and increases the number of active hosts, resulting in higher power consumption. Figure 9 depicts the CloudSim Plus simulation workflow. In this experiment, the round-robin algorithm was integrated into CloudSim Plus to manage the load on the VM host. Once the first VM host has been loaded, this round-robin algorithm will automatically divide the load between VM hosts, which will be beneficial for cloud users in terms of time savings and cost.

Figure 9.

Simulation results of CloudSim Plus based on the round-robin VM allocation policy.

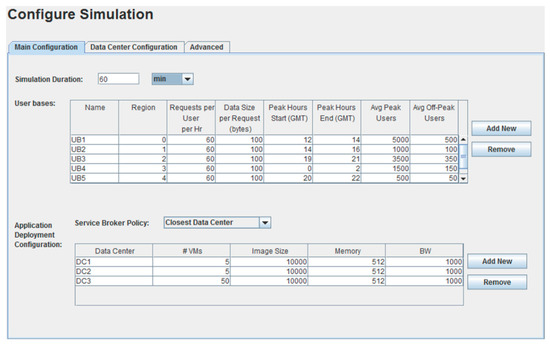

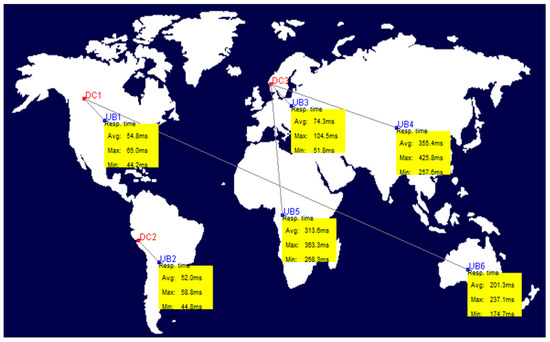

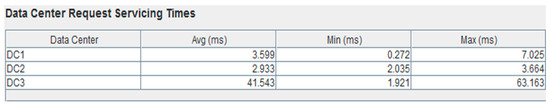

6.3. CloudAnalyst

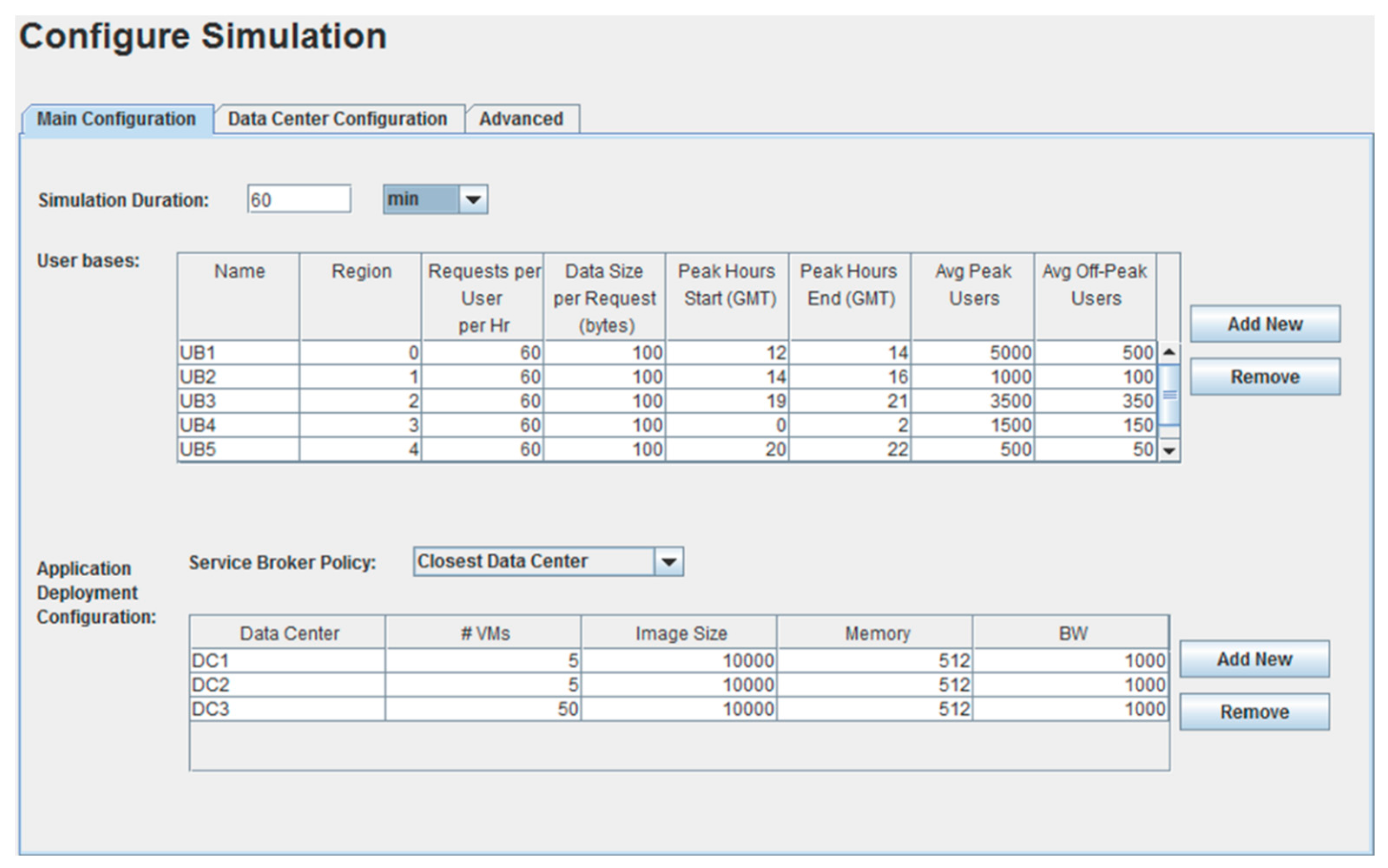

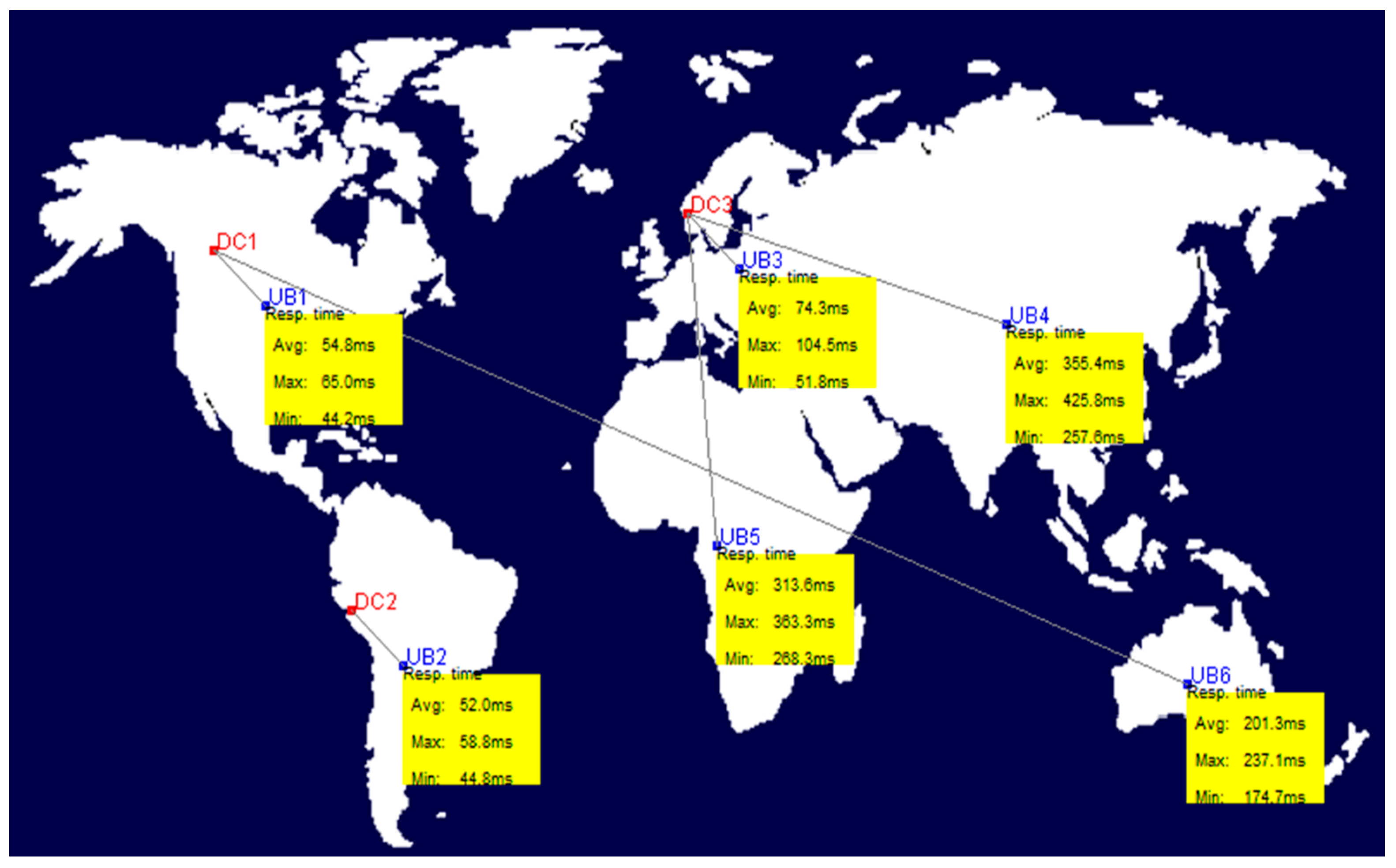

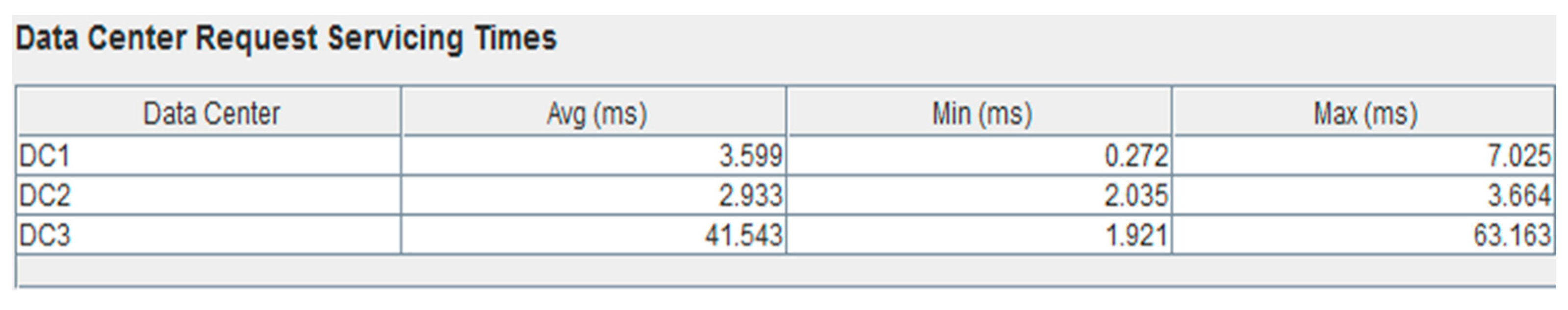

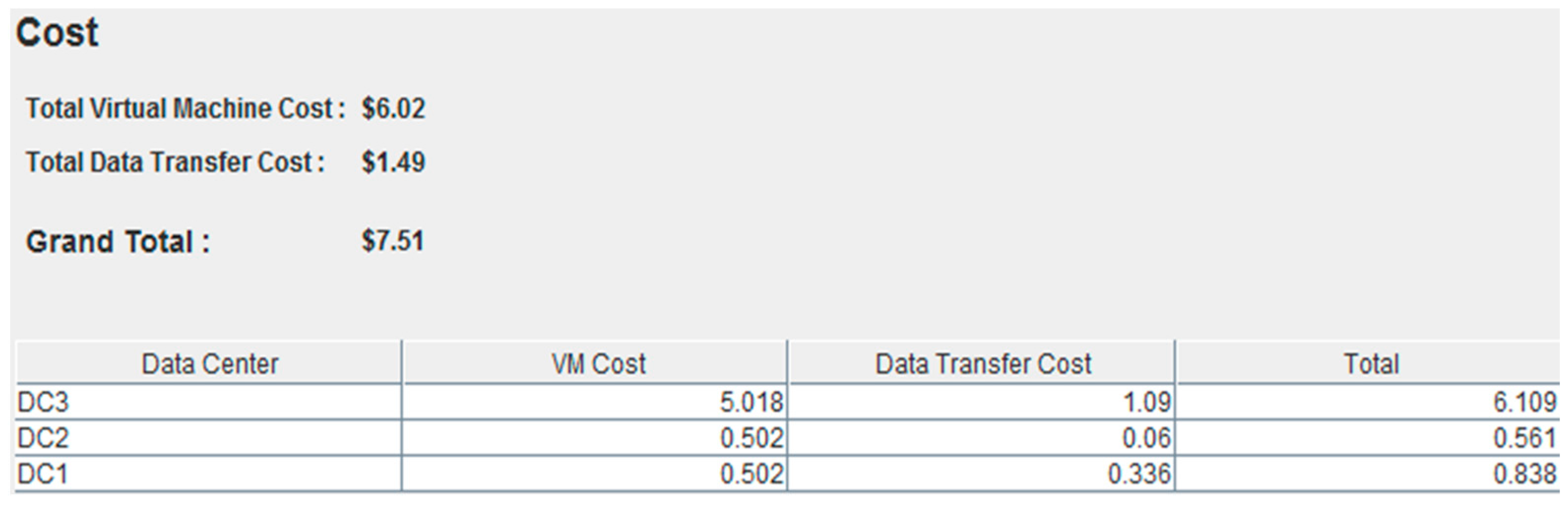

Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 show the workflow of the CloudAnalyst simulation method. In this experiment, we have six UBs for three DCs, which means that there are two UBs on one DC to check the response time of DCs. According to the result, DC 1 and DC 2 have five VMs to execute the cloud user tasks, and DC 3 has 50 VMs.

Figure 10.

Settings of simulation duration with closet DC SB policy.

Figure 11.

Simulation results of DC request servicing time [1].

Figure 12.

Simulation results of DC request servicing time.

Figure 13.

Simulation results of DC, VM, and data transfer costs.

We pretend that an internet application is running in three different DCs around the world in this experiment. The service proximity policy is used to route user traffic to the DC that has the shortest network latency. This simulation will take approximately one hour to complete.

CloudAnalyst displays the regions with a response to time results when the simulation is completed, as depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 13 depicts the cloud infrastructure, which includes six geographically dispersed UBs and three DCs with 5 to 50 VMs.

6.4. iFogSim

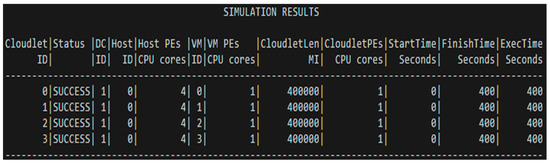

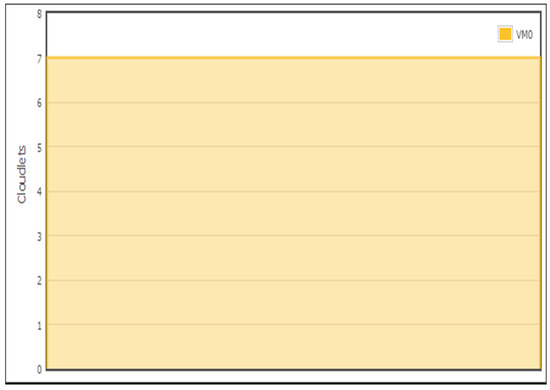

The scenario below was created to add iFogSim’s modeling and simulation capabilities to the test. The amount of CPU time consumed by the host is determined by this scenario. The simulation environment consists of four VMs, some hosts (PEs) equal to the number of VMs, and VMs (PEs) for implementation purposes.

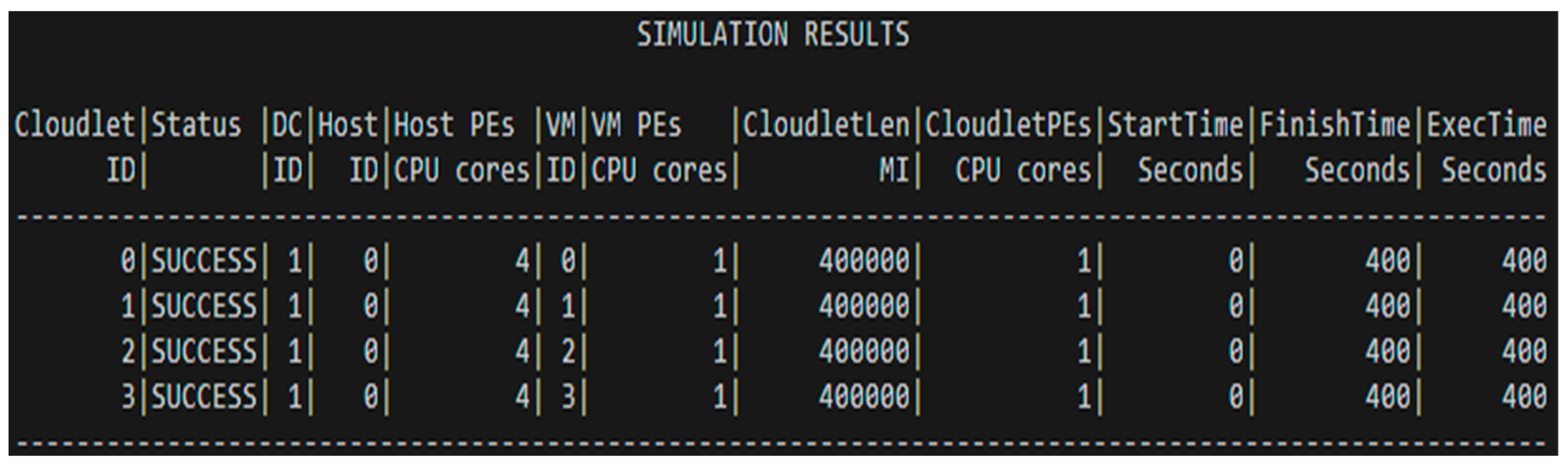

The iFogSim analysis is based on a DC with one host that places two VMs to run one cloudlet each and receives notifications when a host is allocated or reallocated to each VM. The example uses the new VM listeners to get these notifications while the simulation is running. It also shows how to reuse the same listener object in different VMs. Figure 14 shows the workflow of the iFogSim simulation. According to this experiment, we have one DC with four VMs to check the time of the user on cloud resources. This experiment is to check the progress of VMs that are used by cloud users.

Figure 14.

Simulation results of iFogSim based on the DC with one host that places two VMs.

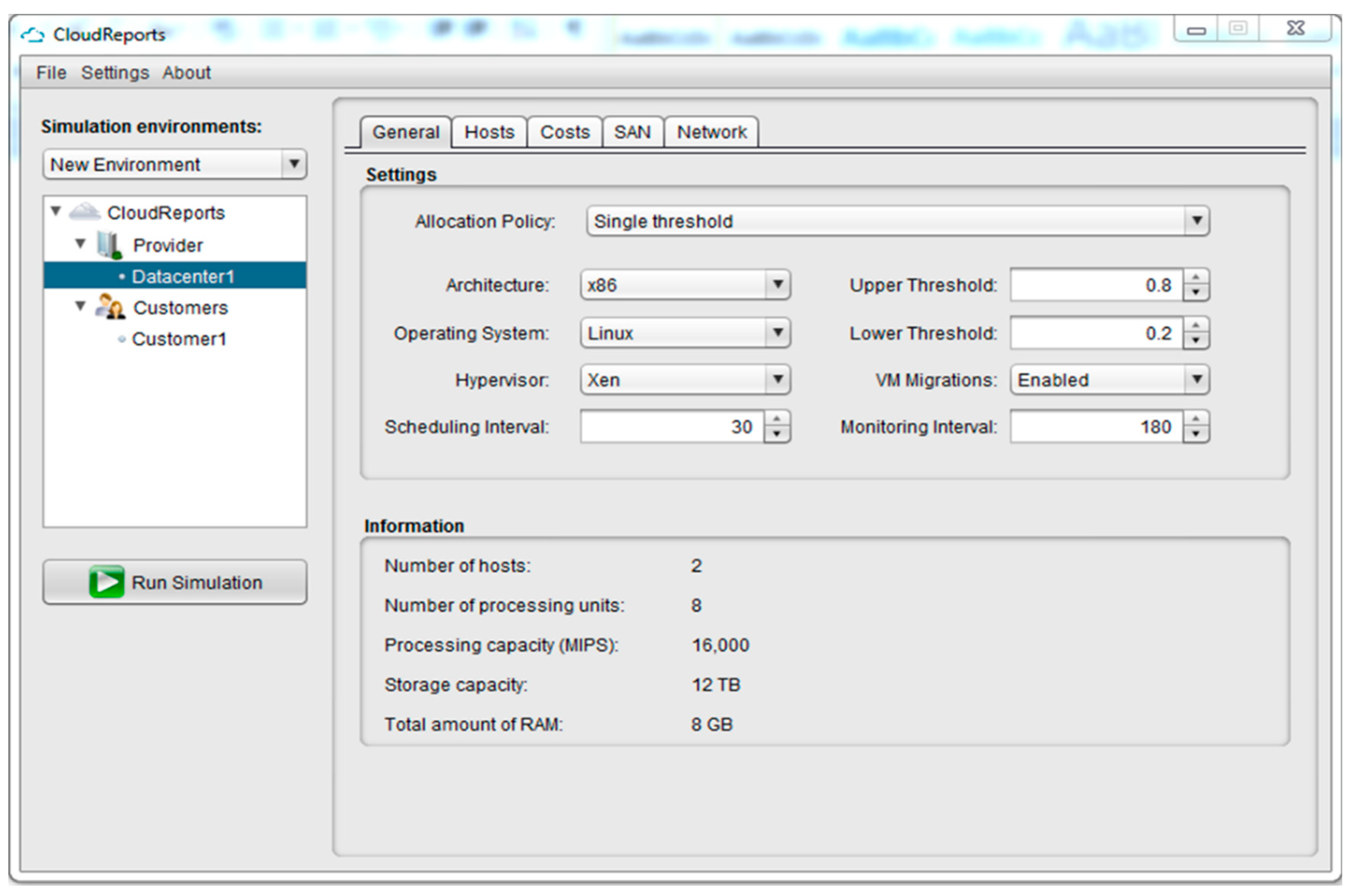

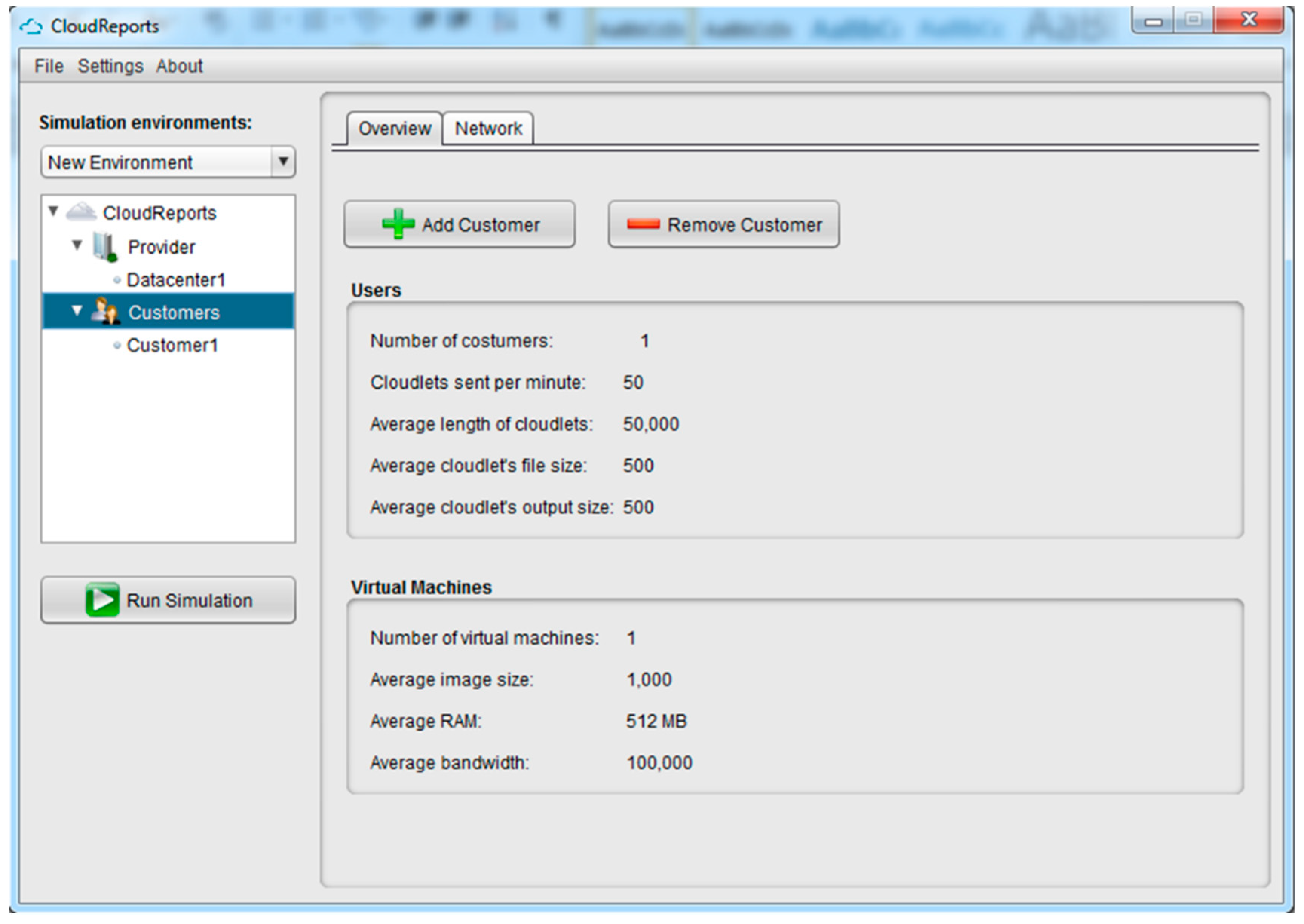

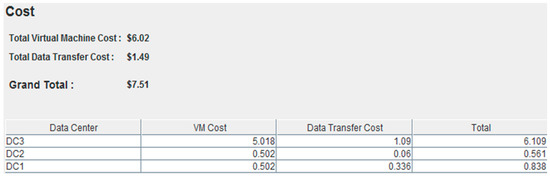

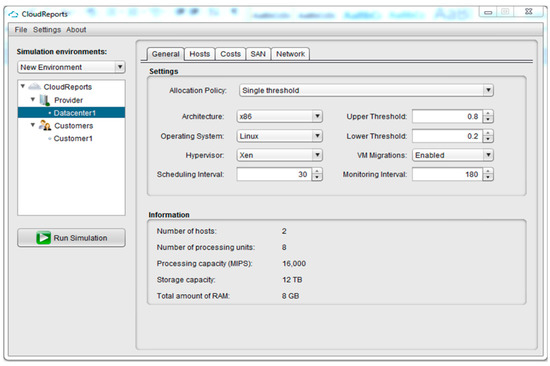

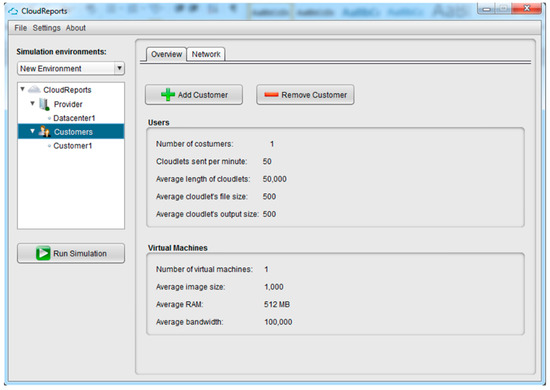

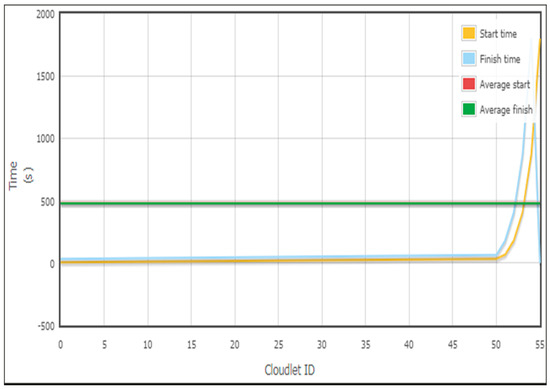

6.5. CloudReports

The simulation set in this experiment consists of one DC and two hosts to demonstrate the capabilities of CloudReports (physical machines). Each host has a single CPU core (capable of 16,000 MIPS computing), 8 GB of RAM, and 12 TB of storage. In this scenario, a VM with 500 and 1000 MIPS compute volumes is running on the host. These VMs have 512 MB of RAM and 10 GB of storage for implementation. To begin this experiment in CloudReports, the DC must first change the host configuration and then add user privileges, as illustrated in Figure 15 and Figure 16. When the simulation is complete, CloudReports generates the results and displays them as HTML reports. Among them are charts for resource utilization, ET, power consumption, and overall resource utilization of each DC.

Figure 15.

Simulation results of the DC based on the single threshold allocation policy.

Figure 16.

Simulation results of customers based on VMs.

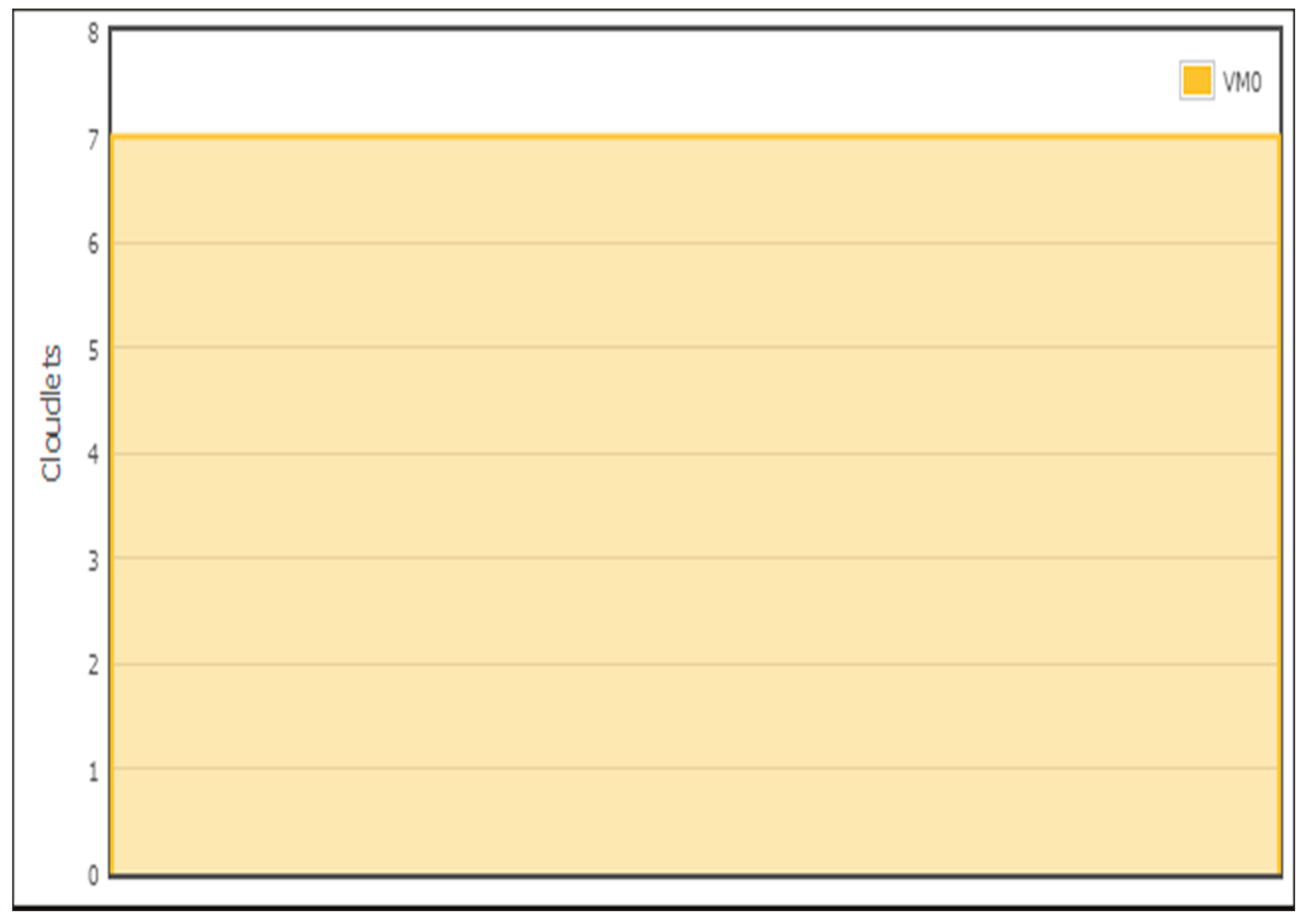

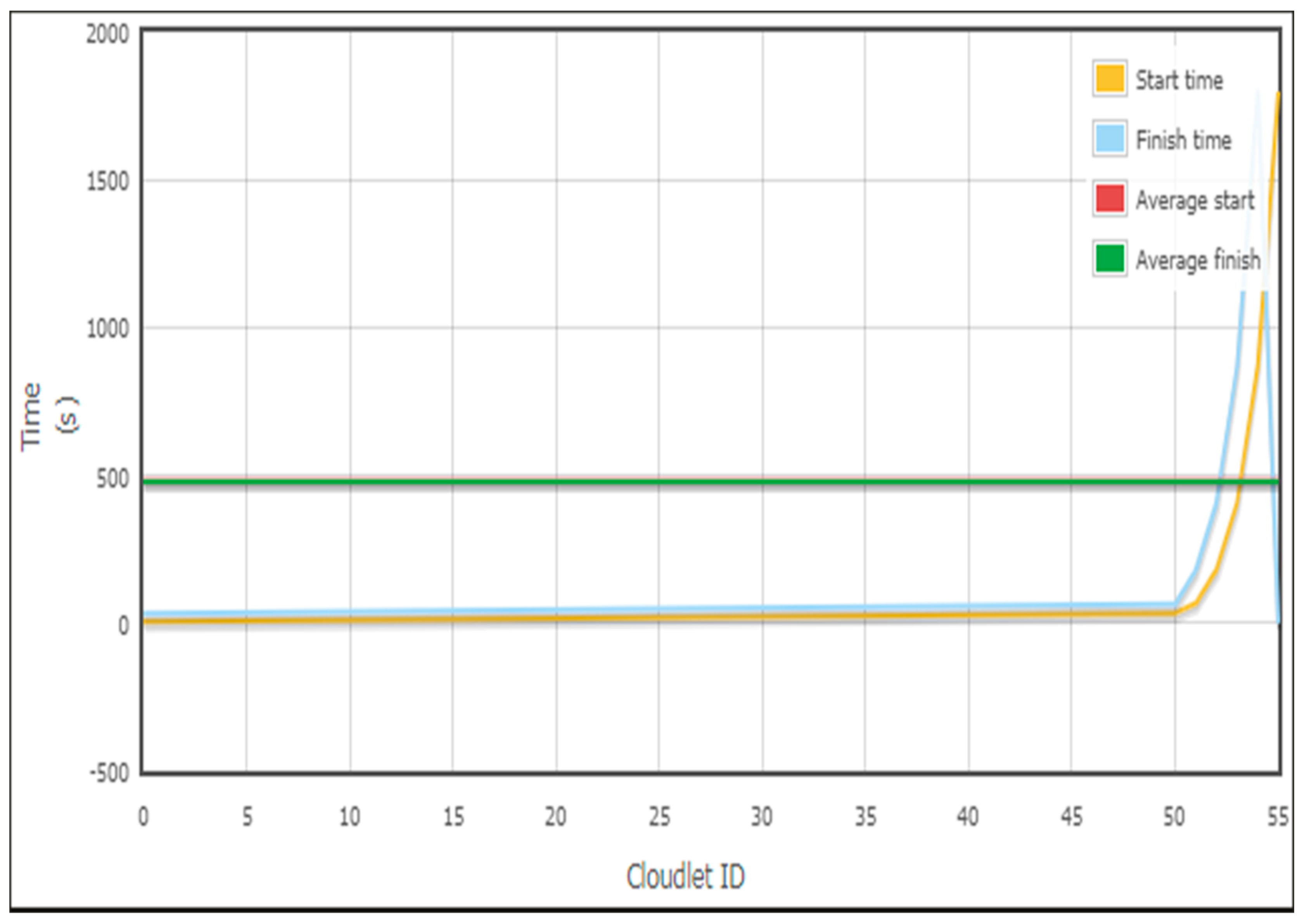

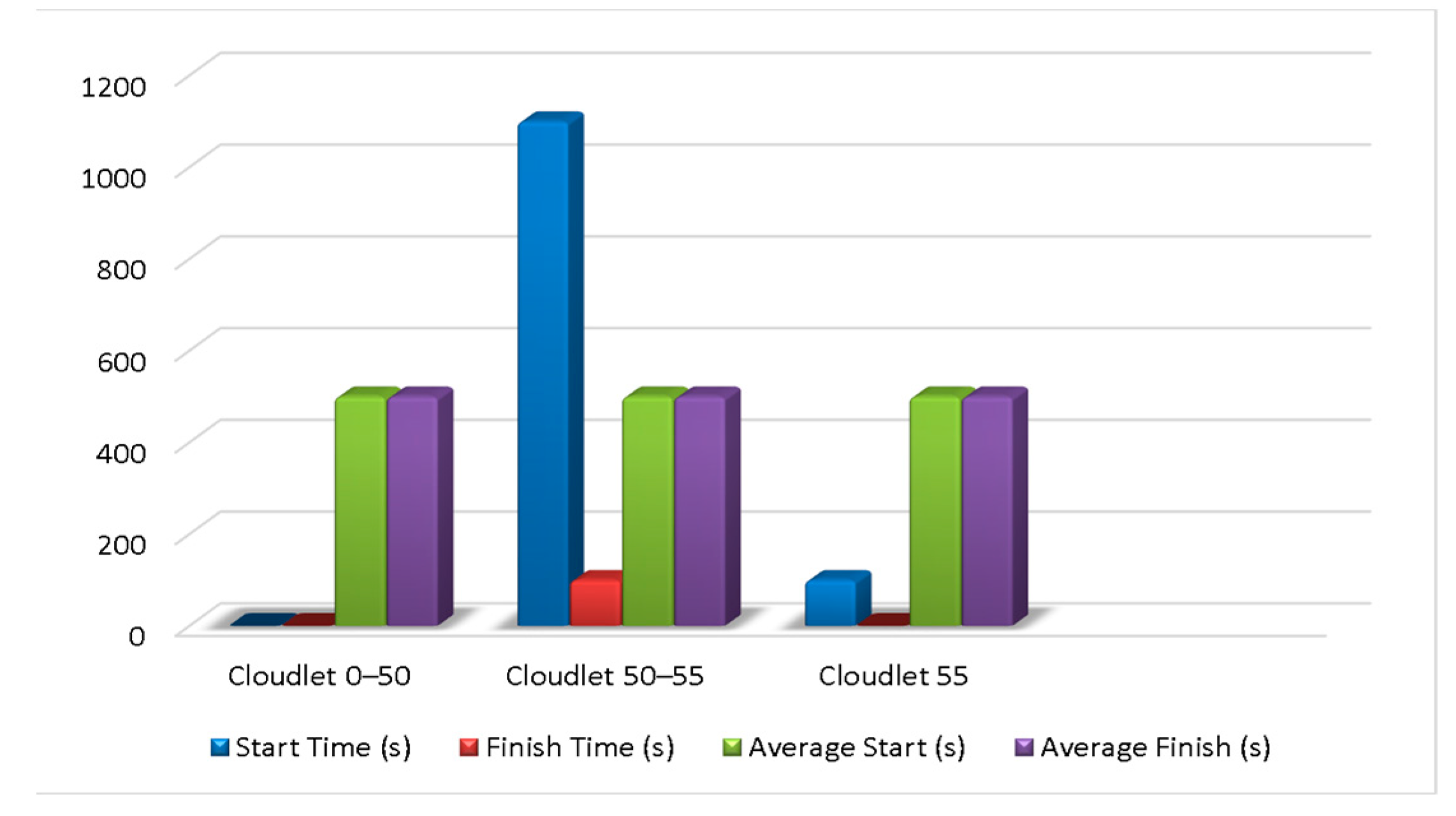

Figure 17 shows an analysis of the number of successful cloudlets executed in a VM with the current DC, and Figure 18 shows the total time in seconds for each successful cloudlet run in the current DC, both of which are generated by CloudReports. This experiment is based on data from cloud users related to the uploading time of cloud data into the cloud service. Based on the results, cloud users can upload the data in the fastest way because they have 16,000 MIPS of processing capacity that is based on a single-threshold allocation policy that is fast for the cloud users.

Figure 17.

Simulation results of the number of successful cloudlets executed in a VM with the current DC.

Figure 18.

Simulation results of ET for the customer’s cloudlet.

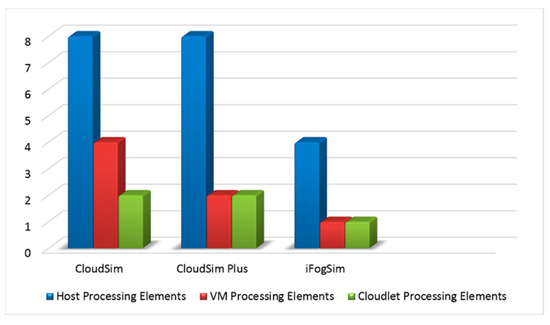

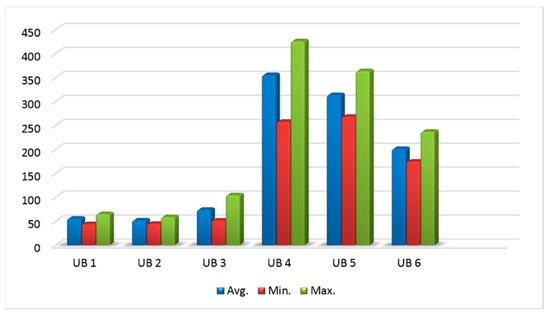

6.6. Result Analysis

Results for simulators with parameters are listed in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10. Table 8 shows the results of the cloud simulation models discussed in this research. CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports are based on HPE, VM PE, and cloudlet PE parameters. Table 9 displays the findings of the cloud simulation models. CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports are based on UB parameters for Avg, Min, and Max with closet DC SB policies. Table 10 shows the results of CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports based on various ET analysis parameters for a customer cloudlet.

Table 8.

Processing element comparison of cloud simulators.

Table 9.

UB parameter comparison of cloud simulators.

Table 10.

Cloudlet parameter comparison of cloud simulators.

6.7. Performance Comparison of Simulators (Parameters)

The results received in Section 6 come from a comparison of five simulator metrics (HPEs; VM PEs; cloudlet PEs; UB Avg, Min, and Max; and cloudlet ID Start Time, Finish Time, Average Start, and Average Finish) for each of the five simulators (CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReport).

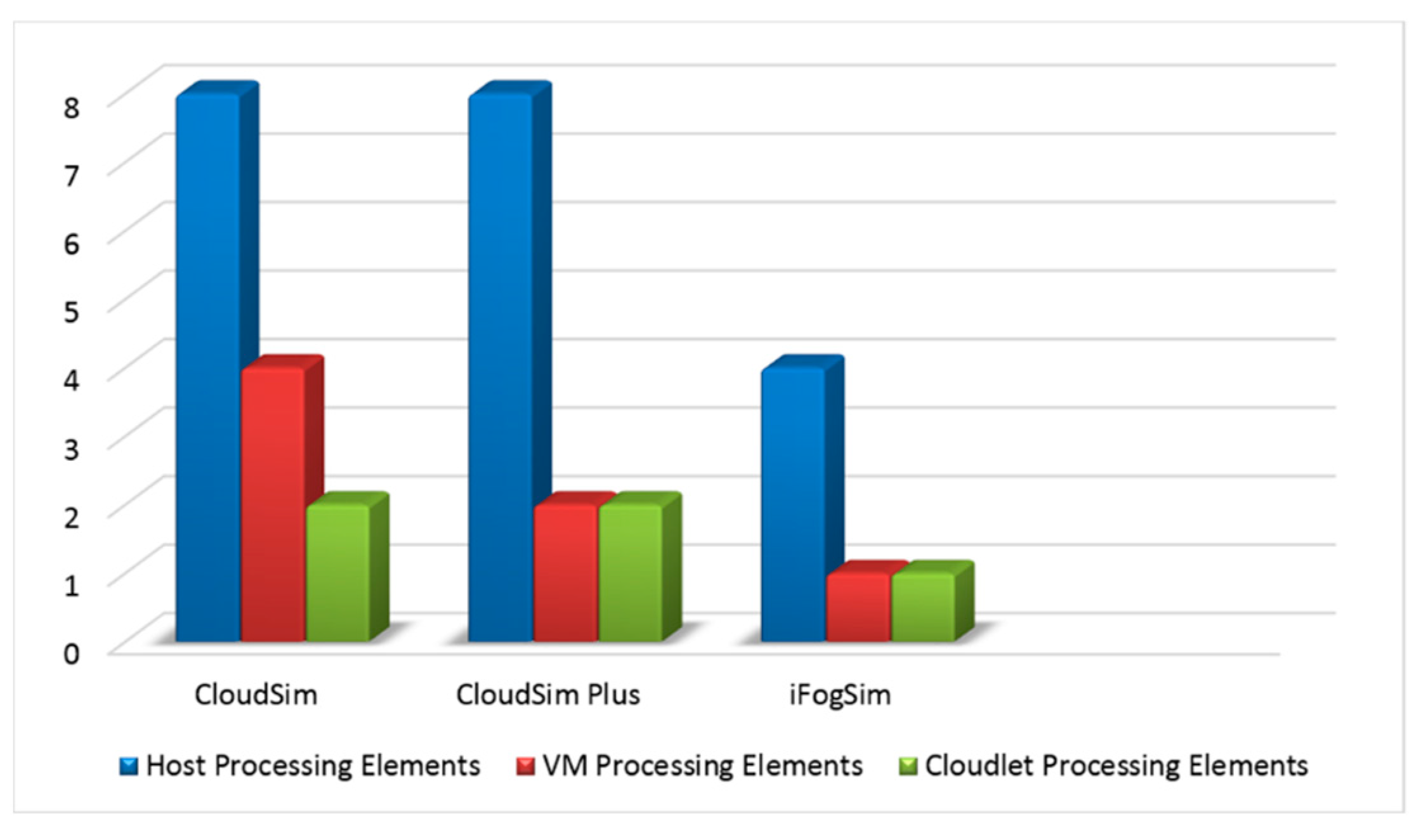

Figure 19 shows HPEs, VM PEs, and cloudlet PEs based on CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, and iFogSim. As it is shown, both CloudSim and CloudSimPlus are equal on HPEs, while the VM PEs and cloudlet PEs show a lower output value. Furthermore, iFogSim, compared to the other two simulators, is equal on VM PEs and cloudlet PEs, while the HPEs showed a higher output value than them.

Figure 19.

Performance comparison of the host, VM, and cloudlet PEs.

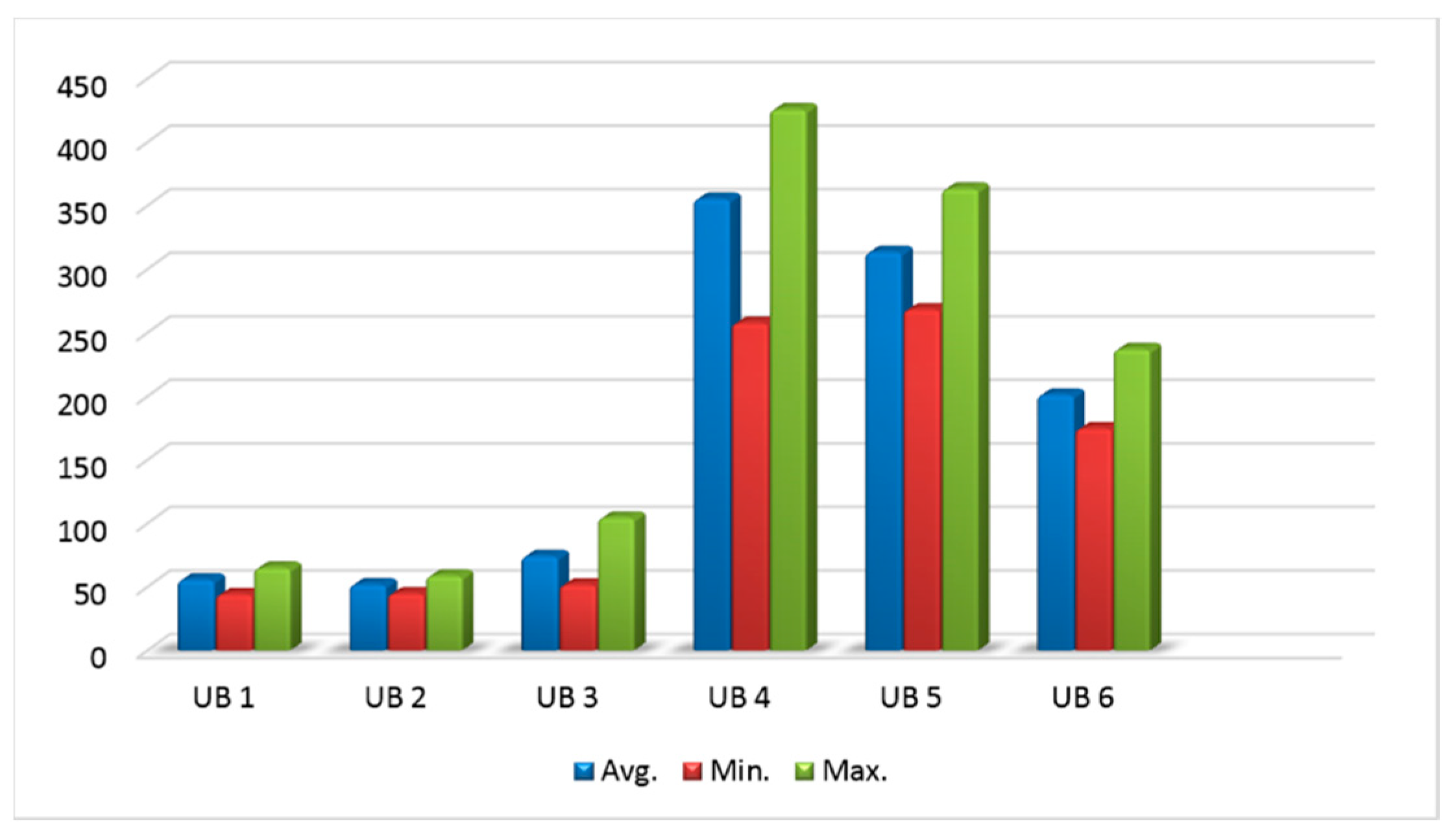

Figure 20 shows a UB of 1 to 6 based on CloudAnalyst, as it shows UB 3 to UB 6 are different on Avg, Min, and Max, while UB 4 Min and UB 5 Min are almost equal. Furthermore, UB 1 Avg, Min, and Max and UB 2 Avg, Min, and Max are almost equal, while UB 3 Avg, Min, and Max and UB 6 Avg, Min, and Max showed a higher output value than them.

Figure 20.

Performance comparison of six UBs based on Avg, Min, and Max values.

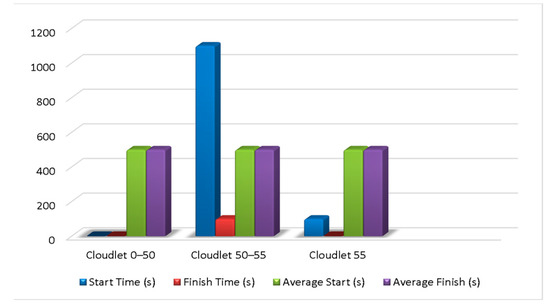

Figure 21 shows the cloudlet parameters: Start Time, Finish Time, Avg Start, and Avg Finish in seconds based on CloudReports. As it is shown, Cloudlet 0–50 start and finish times are equal, and Cloudlet 50–55 start, finish, Avg start, and Avg finish times are different, while the Cloudlet 55 finish time is equal to Cloudlet 0–50. Furthermore, Cloudlet 55 start, Avg start, and Avg finish times have different output values than those of Cloudlet 0–50.

Figure 21.

Performance comparison of cloudlet ID based on start, finish, Avg start, and Avg finish times in seconds.

7. Discussion

The results of the CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports simulators are discussed in this section. Cloud simulation parameters such as host, VM, cloudlet, UB, and ET, and comparison of simulation tools vs. non-simulation tools are also discussed. CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports enable different users to use a DC by employing various cloud-based simulations. Figure 7 shows the simulation capabilities of CloudSim while representing the graphical analysis of HPEs, VMPEs, and cloudlet PEs based on CloudSim. Figure 8 is based on CloudSim Plus. The CE is composed of six geographically dispersed UBs with DC 1 to 3, and three 5, 5, and 50 VM DCs, as shown in Figure 10. Based on the SB strategy, which picks the nearest DC in consideration of the lowest network delay, user-base traffic is routed to the DC. The simulation is 60 minutes long. After the simulation is done, CloudAnalyst displays the regions with time response data, as expressed in Figure 11. Analysis of the results can also be performed by exporting an a.pdf file, which includes comprehensive tables and charts. Figure 12 and Figure 13 are descriptive snapshots for each DC of a request’s servicing time and cost information, respectively. Figure 14 is based on iFogSim. Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the simulation environments of CloudReports, and Figure 17 and Figure 18 represent the number of cloudlets that the actual DC user has successfully performed using CloudReports and show the total time in seconds for each cloudlet to be successfully executed in the current DC.

7.1. Prominent Cloud Simulators

Q1: What is the motivation behind the simulator’s development?

Response: These simulators are modern and up-to-date, complete, and well-reported. Furthermore, they are cost-effective, provide results with graphical representation, and display effective performance.

Q2: What are the features or characteristics of cloud simulators?

Response: These are easy to use and expand, allowing users to model, simulate, and evaluate CC infrastructure and application services.

Q3: What is the scope of extension or application of the targeted cloud simulators?

Response: These simulators are used in PaaS, IaaS, and SAAS.

7.2. Research Questions

Q1: What parameters would be used for the comparison of simulation tools vs. non-simulation tools?

Response: We have used different parameters for the comparison of simulation tools vs. non-simulation tools such as host, VM, cloudlet, UB, and ET.

Q2: What metrics are covered in the cloud simulators that are targeted?

Response: We have covered different metrics for the cloud simulators, such as host, VMs, cloudlet, UBR, and ET.

Q3: What are the energy-consuming parameters found in the selected cloud simulators?

Response: We have found energy-consuming parameters such as workload, cluster, server host, VM, network, storage, CPU, and memory.

7.3. Simulation Setup of Cloud Simulators

We used CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports simulators for analysis to help researchers and readers in the real-time cloud environment. Table 11 shows the hardware specifications for an experiment.

Table 11.

Hardware specifications for the experiment.

8. Recommendations

Access to genuine cloud infrastructure is required for systems administrators, cloud experts, and even researchers to conduct real-time experiments and put new algorithms and approaches into practice. Before going live, it is critical to evaluate performance and thoroughly identify any potential security concerns. Modeling and simulation tools have saved us from such difficulties. A CC simulator is required to view an implementation scenario in real-time. Many CC simulators are being developed to assist academics, systems administrators, cloud specialists, and network administrators in assessing the real-time performance of CC environments. Since free and open-source simulators provide an environment for DL and experimentation, the trend is to focus on these simulators for all types of complicated and real-world CC problems.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

The ever-growing popularity and difficulty of computing systems make simulation software an essential option for creating, installing, controlling, and evaluating a system’s efficiency. Simulators of CC have been used in the evaluation of trade-offs between cost and reliability in PAYG settings. The analysis, therefore, aimed to present a collection of simulation resources appropriate for cloud architecture. A wide range of tools, namely CloudSim, CloudSim Plus, CloudAnalyst, iFogSim, and CloudReports, are addressed. Extensive analysis of cloud simulators that consider multiple hosts and VMs as different workloads and system configurations has been provided. The results of the performance comparison of simulator parameters are shown in Section 6.

In future work, the cloud simulators can be extended to develop innovative and advanced integrating technologies such as ML and AI to respond to the circumstances dynamically. Another area of research lies in expanding the cloud simulation tools’ functionality to fit ML algorithms, such as NB, RF, SVM, etc., in the simulation tools. These ML algorithms can be integrated with FTCloudSim, Dynamic CloudSim, etc. for cloud service reliability enhancement simulations. The enhancement of the simulation module graphics also has potential.

List of Abbreviations

Table 12 shows the list of abbreviations that are used throughout the whole manuscript. Details are mentioned below.

Table 12.

List of abbreviations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.S.; Methodology, M.A.S. and M.M.A.; Validation, M.A.S. and M.M.A.; Investigation, M.A.S. and M.M.S.; Resources, M.A.S. and M.M.A.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.A.S. and M.M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A.S., M.M.A. and M.M.S.; Visualization, M.A.S.; Supervision, M.A.S. and M.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research will be funded by the Multimedia University, Department of Information Technology, Persiaran Multimedia, 63100, Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank their mentors who have always helped and guided this research to make it possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

References

- Bahwaireth, K.; Tawalbeh, L.; Benkhelifa, E.; Jararweh, Y.; Tawalbeh, M.A. Experimental comparison of simulation tools for efficient cloud and mobile cloud computing applications. J. Inf. Secur. 2016, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Sahoo, B.; Parida, P.P. Load balancing in cloud computing: A big picture. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 32, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Chaturvedi, A. Cloud Computing Characteristics and Services A Brief Review. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Sariya, A.K. A Review: Methods of Load Balancing on Cloud Computing. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Haris, M.; Khan, R.Z. A Systematic Review on Load Balancing Tools and Techniques in Cloud Computing. In Inventive Systems and Control; Suma, V., Baig, Z., Shanmugam, S.K., Lorenz, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 503–521. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.A.; Alam, M.M.; Su’ud, M.M. Performance Evaluation of Load-Balancing Algorithms with Different Service Broker Policies for Cloud Computing. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, N.; Mehta, M.A. Comprehensive and Comparative Study of Cloud Simulators. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Punecon, Pune, India, 30 November–2 December 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, T. Analysis of Energy Consumption on IaaS Cloud Using Simulation Tool. SSRN J. 2020, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissir, N.; ElKafhali, S.; Aboutabit, N. How Much Your Cloud Management Platform Is Secure? OpenStack Use Case. In Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 4; Ahmed, M.B., Kara, İ.R., Santos, D., Sergeyeva, O., Boudhir, A.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 183, pp. 1117–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Bambrik, I. A Survey on Cloud Computing Simulation and Modeling. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, N.; Ghafari, R.; Zade, B.M.H. Cloud computing simulators: A comprehensive review. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 104, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundas, A.; Panda, S.N. An Introduction of CloudSim Simulation tool for Modelling and Scheduling. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), Pune, India, 12–14 March 2020; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Puhan, S.; Panda, D.; Mishra, B.K. Energy Efficiency for Cloud Computing Applications: A Survey on the Recent Trends and Future Scopes. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computer Science, Engineering and Applications (ICCSEA), Gunupur, India, 13–14 March 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hassaan, M. A Comparative Study between Cloud Energy Consumption Measuring Simulators. Int. J. Educ. Manag. Eng. 2020, 10, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A. Energy-driven cloud simulation: Existing surveys, simulation supports, impacts and challenges. Clust. Comput. 2020, 23, 3039–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, M.C.; Oliveira, R.L.; Monteiro, C.C.; Inacio, P.R.M.; Freire, M.M. CloudSim Plus: A cloud computing simulation framework pursuing software engineering principles for improved modularity, extensibility and correctness. In Proceedings of the 2017 IFIP/IEEE Symposium on Integrated Network and Service Management (IM), Lisbon, Portugal, 8–12 May 2017; pp. 400–406. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, A.; Kertesz, A. A survey and taxonomy of simulation environments modelling fog computing. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 101, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusooya, G.; Md, A.Q.; Jackson, C.; Prassanna, J. A review on effective utilization of computational resources using cloudsim. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nandhini, J.M.; Gnanasekaran, T. An Assessment Survey of Cloud Simulators for Fault Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Computing and Communications Technologies (ICCCT), Chennai, India, 21–22 February 2019; pp. 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Arseniev, D.G.; Overmeyer, L.; Kälviäinen, H.; Katalinić, B. Cyber-Physical Systems and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 95. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, M.I.; Chishti, M.A. Offloading in Cloud and Fog Hybrid Infrastructure Using iFogSim. In Proceedings of the 2020 10th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science and Engineering (Confluence), Noida, India, 29–31 January 2020; pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D.; Shahhosseini, S.; Mehrabadi, M.A.; Donyanavard, B.; Lim, S.S.; Rahmani, A.M.; Dutt, N. Dynamic iFogSim: A Framework for Full-Stack Simulation of Dynamic Resource Management in IoT Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Omni-layer Intelligent Systems (COINS), Barcelona, Spain, 31 August–2 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhfakh, F.; Kacem, H.H.; Kacem, A.H. Simulation tools for cloud computing: A survey and comparative study. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACIS 16th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS), Wuhan, China, 24–26 May 2017; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Motlhabane, N.; Gasela, N.; Esiefarienrhe, M. Comparative Analysis of Cloud Computing Simulators. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2018; pp. 1309–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, J.; Svorobej, S.; Giannoutakis, K.M.; Tzovaras, D.; Byrne, P.J.; Östberg, P.O.; Gourinovitch, A.; Lynn, T. A Review of Cloud Computing Simulation Platforms and Related Environments. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science, Porto, Portugal, 24–26 April 2017; pp. 679–691. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, K.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.; Nazmy, T.T.; Salem, A.-B.M. Cloud simulators—An evaluation study. Int. J. Inf. Model. Anal. 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Dogra, S.; Singh, A.J. Comparison of Cloud Simulators for effective modeling of Cloud applications. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 99, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Perez Abreu, D.; Velasquez, K.; Curado, M.; Monteiro, E. A comparative analysis of simulators for the Cloud to Fog continuum. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 101, 102029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Vahid Dastjerdi, A.; Ghosh, S.K.; Buyya, R. iFogSim: A toolkit for modeling and simulation of resource management techniques in the Internet of Things, Edge and Fog computing environments: iFogSim: A toolkit for modeling and simulation of internet of things. Softw. Pract. Exper. 2017, 47, 1275–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaratzis, A.T.; Giannoutakis, K.M.; Tzovaras, D. Energy Modeling in Cloud Simulation Frameworks. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 79, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.R.; Shanmugam, R.; Saini, K.; Kumar, S. Cloud Computing Tools: Inside Views and Analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 173, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J.A.P.; Singh, M. Comprehensive study of multi-resource cloud simulation tools. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2017, 4, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashalatha, R.; Agarkhed, J.; Patil, S. Analysis of Simulation Tools in Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Wireless Communications, Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), Chennai, India, 23–25 March 2016; pp. 748–751. [Google Scholar]

- Beena, T.L.A.; Lawanya, J.J. Simulators for Cloud Computing—A Survey. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Suryateja, P.S. A Comparative Analysis of Cloud Simulators. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 2016, 8, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, R.; Bawa, R.K. Quality based cloud simulators: State-of-the-art road ahead. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing (PDGC), Solan, India, 22–24 December 2016; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Aleem, M.; Sajjad, A. Energy-Aware Cloud Computing Simulators: A State of the Art Survey. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 2018, 6, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitha, J. Study of Simulation Tools in Cloud Computing Environment. J. Indep. Stud. Res. Comput. 2018, 7, 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Shakir, M.S.; Razzaque, E.A. Performance Comparison of Load Balancing Algorithms using Cloud Analyst in Cloud Computing. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vashistha, A.; Sholliya, S. Comparative study of open source cloud simulation tools. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2017, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.A. A Study on Simulation Tools in Cloud Computing. J. Glob. Res. Comput. Sci. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, M. A Study and Analysis on Simulators of Cloud Computing Paradigm. Int. J. Adv. Trends Appl. 2017, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Maarouf, A.; Marzouk, A.; Haqiq, A. Comparative Study of Simulators for Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Cloud Technologies and Applications (CloudTech), Marrakech, Morocco, 2–4 June 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pagare, J.D.; Koli, D.N.A. Design and simulate cloud computing environment using cloudsim. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2015, 6, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.; Beri, R. Cloud Computing: A Survey on Cloud Simulation Tools. J. Glob. Res. Comput. Sci. 2016, 2, 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.A.A.G.; Priyadharshini, R.; Leavline, E.J. Analysis of Cloud Environment Using CloudSim. In Artificial Intelligence and Evolutionary Computations in Engineering Systems; Dash, S.S., Naidu, P.C.B., Bayindir, R., Das, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, E.; Nogueira, B. Performability Evaluation of a Cloud-Based Disaster Recovery Solution for IT Environments. J. Grid Comput. 2019, 17, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.O.; Khan, R.Z. Cloud Computing Modeling and Simulation Using CloudSim Environment. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 5439–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.S.; Sharma, M. A Critical Review and Analysis of Cloud Computing Simulators. Int. J. Latest Trends Eng. Technol. 2016, 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.A.; Islam, N.; Alam, M.M.; Su’ud, M.M.; Musa, S. A Comprehensive Study of Load Balancing Approaches in the Cloud Computing Environment and a Novel Fault Tolerance Approach. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 130500–130526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.A.; Islam, N.; Alam, M.M.; Mazliham, M.S.; Musa, S. Towards Resilient Method: An exhaustive survey of fault tolerance methods in the cloud computing environment. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.; Cañizares, P.C.; de Lara, J. CloudExpert: An intelligent system for selecting cloud system simulators. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 187, 115955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Tyagi, S.; Kumar, P. Comparative Analysis of Various Simulation Tools Used in a Cloud Environment for Task-Resource Mapping. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Paradigms of Computing, Communication and Data Sciences, Kurukshetra, India, 7–9 May 2021; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Saadi, Y.; El Kafhali, S. Energy-efficient strategy for virtual machine consolidation in cloud environment. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 14845–14859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, D.G.; da Silva, R.A.C.; Madeira, E.R.M.; da Fonseca, N.L.S.; Medhi, D. SinergyCloud: A simulator for evaluation of energy consumption in data centers and hybrid clouds. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2021, 110, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, S.; Bhateja, V.; Mohanty, J.R.; Udgata, S.K. Smart Intelligent Computing and Applications: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Smart Computing and Informatics, Volume 1; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 159. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoutakis, K.M.; Filelis-Papadopoulos, C.K.; Gravvanis, G.A.; Tzovaras, D. Evaluation of Self-Organizing and Self-Managing Heterogeneous High Performance Computing Clouds through Discrete-Time Simulation. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).