Abstract

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the density of the midpalatal suture (MPS) of individuals with maxillary expansion (rapid maxillary expansion, RME), surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARPE), and miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) through computed tomography. An electronic search was performed in four databases, MEDLINE via PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in February 2023 and updated in April 2023, using previously established search strategies. Studies were retrieved without restrictions in terms of data, language, or publication status. The risk of bias assessment was based on a quality assessment tool for before-and-after studies. Ten studies were included in our systematic review, and nine studies were included for our quantitative analysis. The analyses were performed by subgroup according to the evaluation of the region, anterior, middle, and posterior, including the three types of treatment: RME, SARPE, and MARPE. Heterogeneity was high for the three regions (anterior 95%, medium 97%, and posterior 84%) and a statistical difference was found in two of the three regions (anterior p = 0.06, medium p = 0.031, and posterior p < 0.001). There is not enough evidence to state that the MPS density is different after 6 months of RME in the anterior and middle regions; the bone density values for SARPE and MARPE suggest that 6 or 7 months after expansion, there is still no bone density similar to the initial one in the three regions.

1. Introduction

Maxillary transverse deficiency is characterized by an upper arch with reduced transverse dimensions, which can be clinically identified by an oval or deep palate, V-shaped arch, and wide buccal corridor. Its etiology is mainly related to environmental factors, predominantly mouth breathing and persistent oral habits [1].

Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is the conventional method for transverse maxillary deficiency treatment; it can effectively enlarge the maxilla by applying a rapid transverse force of high magnitude to the upper teeth resulting in the opening of the midpalatal suture [2]. The midpalatal suture (MPS) is a single suture that matures and structurally changes under the influence of mastication, hormones, genetics, and mechanical factors. The closure of the suture does not necessarily imply the end of skeletal body maturation. In addition, there is a high amount of individual and morphological variation [3,4].

However, in late adolescence and in adults, there is limited skeletal expansion due to the interdigitation of the MPS that occurs with increasing age [3]. Skeletal maturation during adolescence and young adulthood leads to the gradual closure of the palatine suture, starting from the back and moving forward. As a result, the skeletal response to RME decreases. In these cases, conventional RME can produce side effects, such as the failure to separate the maxilla, labial tipping of the crown, root resorption, and marginal bone resorption [5]. The most common treatment for these cases is surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARPE) [6]. It is an invasive procedure with high financial costs and requires hospitalization and general anesthesia. In this context, MARPE emerges as a less invasive and efficient option in patients without growing potential. Thus, a personalized assessment of the patient’s skeletal maturation stage in the area of interest could be an important predictor of RME success [7].

To assist in the clinical decision to treat a patient using conventional RME or SARPE, indicators of MPS maturation have been proposed, which include the following: suture morphology on occlusal radiography [8], skeletal maturation indicator on hand and wrist radiography [9], indicators of cervical vertebrae maturation (CVM) in teleradiography [10], and a classification of five stages of maturation of the median palatine suture proposed by Angelieri et al. [11]. Grünheid et al. proposed a new method for evaluating the maturation of the palatine suture by determining the bone density of this region, using cone-beam computed tomography, which demonstrated a significant correlation with the amount of skeletal response to RME treatment assessed in their study [7].

An important clinical decision is the retention period after RME; the literature reports a variation from 2 to 12 months. In general, a period of 3 months is used [12]. Although it is a plausible period for RME, this time may not be enough for SARPE. Studies state that a retention period of 6 months after RME allows for suture reorganization with a similar density to that before expansion [13,14]. However, 7 months after SARPE, the density values showed that the remineralization was still incomplete, and it was questionable if the ossification present up to that time would be able to resist the forces exerted by adjacent bone structures and if recurrence could be avoided [15,16].

In recent years, clinical practice has benefited from computed tomography (CT) as it has diagnostic advantages over traditional two-dimensional images [17]. CT allows for more accurate assessments and diagnoses, is an efficient, non-invasive, and fast method, and allows for reliable linear and angular measurements [18]. Using CT, it is possible to visualize the palatine suture without any overlapping of anatomical structures [19].

Thus, the aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the density of the MPS of individuals before and after RME, SARPE, and miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion of the maxilla (MARPE) through computed tomography to assist in clinical decision making regarding which procedure and device will be the most effective, have more predictable results, and have fewer unwanted side effects. In addition, we gather various findings from the literature on the ideal period for retention after expansion procedures, minimizing the risk of recurrence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This review adheres to the Cochrane Manual for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The PRISMA checklist was utilized as a template [20].

The review protocol was prepared beforehand following the PRISMA-P declaration and registered in PROSPERO under CRD42019118948.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Our clinical question was formulated using the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) format and we defined our inclusion and exclusion criteria (as shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

PICO question.

Inclusion criteria include the following: human clinical trials with prospective or retrospective design; individuals who were received RME, SARPE, or MARPE treatment; and studies in which the bone density of the palatine suture was evaluated before and after intervention by CT.

The exclusion criteria were defined as follows: case reports, case series, review articles, editorials, opinions, studies on syndromic patients, and studies on patients who are systemically compromised or who have cleft lip and/or palate.

2.3. Electronic Search Bases and Search Strategies

Four bibliographic databases, including PubMed via MEDLINE, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), were initially searched in February 2023 and updated in April 2023.

Specific search strategies were developed for each database and consisted of a combination of keywords, as described in Table 2. The databases were configured to send alerts via email in case of indexing of new eligible articles. In addition, a manual search of the reference lists of relevant articles and literature not published in ClinicalTrials.gov was also performed. The studies were retrieved without restrictions in terms of date, language, or publication status.

Table 2.

Specific search strategy for each electronic database.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Collection

After the exclusion of duplicate articles, the list of titles and abstracts was independently reviewed by two reviewers (LMF and NCV) according to the eligibility criteria through predetermined forms. The article was read in full if the title and abstract did not provide sufficient information. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third reviewer (CTM) for their judgment.

After reading the titles and abstracts, the pre-selected articles were read in full according to the eligibility criteria by the two reviewers, and those that met the eligibility criteria were assigned to extract data in spreadsheet format in Excel (Version 16.77, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) to obtain all relevant information. The authors of some studies were contacted via email or social media to verify the eligibility criteria and provide missing data or information, especially with regard to their methodology and sample-related data.

The data collected from the included articles included the following: type of study, type of image, patient (n, sex, and age), intervention, density assessment period, measurement region, statistics, results, and conclusion.

2.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

Methodological quality assessment and risk of bias analysis were performed by two investigators (LMF and COL) in the included studies. The authors utilized the Quality Assessment Tool for Before-and-After Studies (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 24 April 2023)) to evaluate the study. This checklist was developed for medical articles, but it has already been used by other authors to assess the methodological quality and the risk of bias in dentistry studies [21,22] with some adaptations.

Although this tool includes 12 items, as a way of adapting to the types of studies included in this review, three items were removed and the remaining nine were used: (1) if the question or purpose of the study was clearly stated; (2) if the eligibility criteria were pre-specified and clearly described; (3) if the participants were representative of the population; (4) if all eligible participants who met the inclusion criteria were included; (5) if the sample size was large enough to provide confidence in the results; (6) if the intervention was clearly described and consistently performed; (7) if the measurement results were pre-specified, clearly defined, valid, reliable, and consistently evaluated; (8) if the loss to follow-up after initiation of treatment was 20% or less and if these losses were accounted for in the analysis; and (9) if statistical methods were performed to assess changes in pre- and post-intervention measures and if a p-value was provided. For item 5, a study that presents a sample calculation or analysis of the power a posteriori, or if it presents a sample greater than 50 participants, is considered adequate.

When checking the criteria for each item, responses of ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘CD’ (cannot determine), ‘NA’ (not applicable), or ‘NR’ (not reported) were assigned. The studies were classified according to the answers obtained in the qualification tool, applying the following criteria: a quality of “good” for studies with seven to nine answers of “yes”, indicating a low risk of bias; a quality of “fair” for studies with four to six answers of “yes”, indicating a moderate risk of bias; and a quality of “poor” for records with one to three answers of “yes”, indicating lack of information or uncertainty, leading to a high risk of bias.

2.6. Meta-Analysis and Statistics

A meta-analysis was performed using the software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3.2.00089; Biostat, Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA).

The density of the MPS was compared in three regions: anterior, middle, and posterior. The data extracted from the articles and inserted into the software were the means of pre- and post-expansion values and standard deviations. Heterogeneity was tested using the Q-value and I2 index. A random effects model was used, and effect measures for subgroups were presented in meta-analysis graphs (forest plots).

3. Results

3.1. Studies Selection

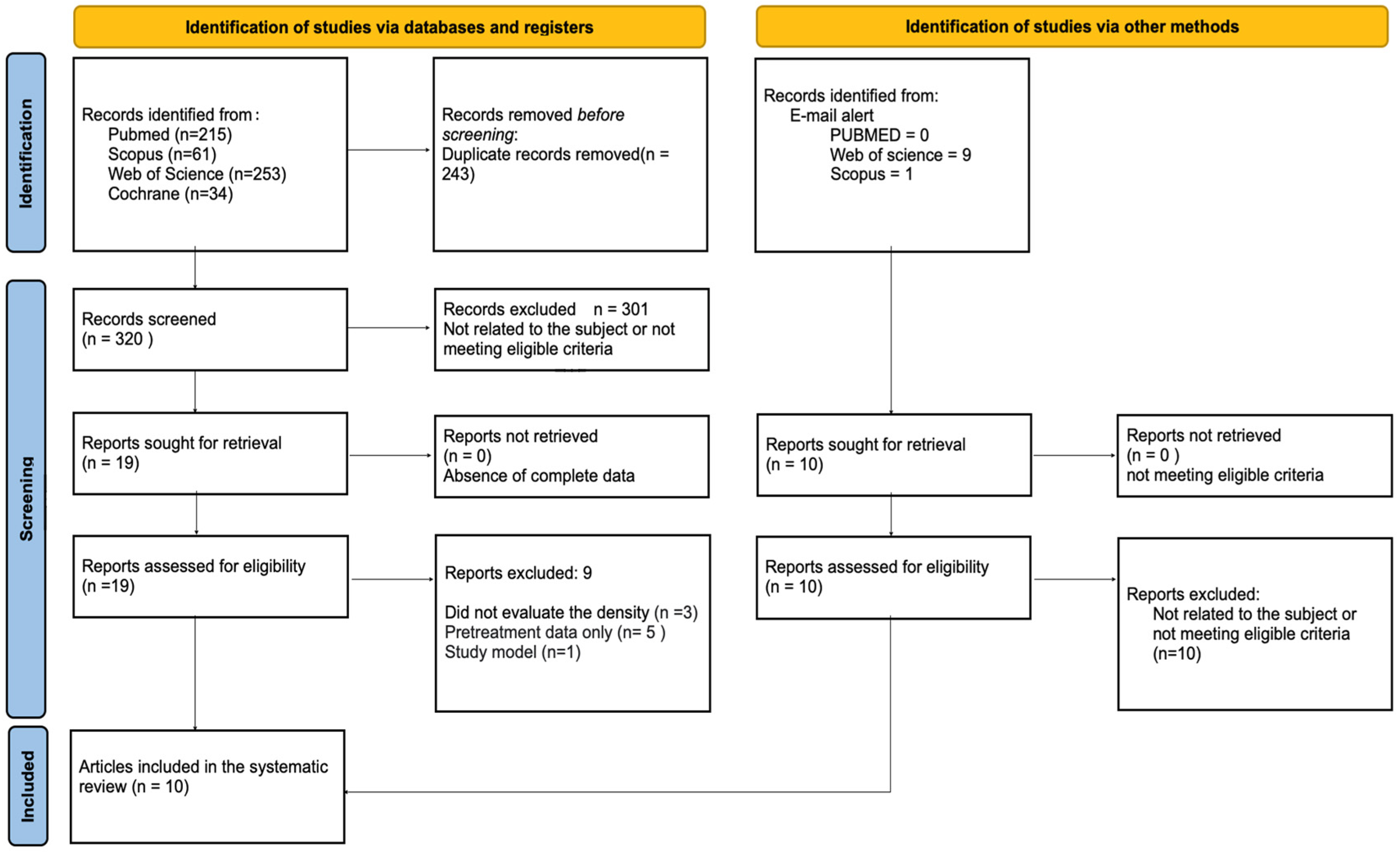

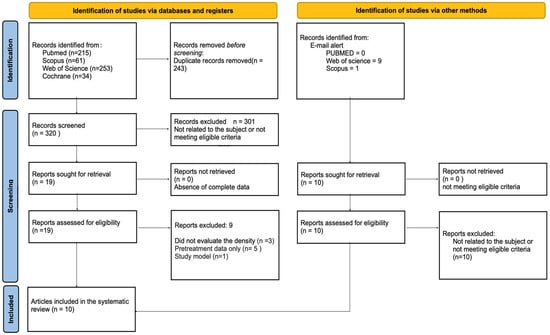

A flowchart of the article selection process is shown in Figure 1. The established search strategy retrieved 563 articles. After removing duplicates, 320 titles and abstracts were reviewed by two reviewers (LMF and NCV) regardless of the eligibility criteria. Twenty articles were pre-selected to be read in full. We were alerted to ten additional articles via email, but none of them were included in this review since the ten articles resulting from the application of the search strategy met the inclusion criteria and were used.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process following the PRISMA guidelines.

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

The descriptive data of the ten included studies are summarized in Table 3, in which it is possible to observe that half of the studies were retrospective [23,24,25,26,27] and the other half were prospective [13,15,16,28,29]. A total of 215 patients were included: 158 females and 57 males.

Table 3.

Descriptive data of the ten included studies.

The transverse maxillary deficiency was corrected by RME in five studies [13,23,24,25,28], by SARPE in three studies [15,16,26], and by MARPE in one study [27]. One author did not report the type of treatment used [29].

All articles analyzed the density of the suture before and after expansion and measured the density in three different regions in the median palatine suture: the anterior, middle, and posterior. All studies measured the density in Hounsfield Units (HU).

Regarding the 3D images used in the studies, five studies used CBCT [16,23,26,27,29] and five studies used CT [13,15,24,25,28]. All the studies provided the scan configuration, including the kVp, mA, field of view (FOV), voxel size, and scan time.

All the studies recorded baseline measurements, called T0 or T1, before expansion. Seven articles evaluated patients for 6 months after expansion [13,16,23,24,26,27,28], two articles evaluated patients for 7 months [13,25], and one article did not specify the assessment time after expansion [29]. The evaluation of the suture by the authors was performed by various methods: two authors evaluated the suture in the coronal view [15,27], seven authors evaluated the suture in the axial view [13,15,16,23,24,25,29], and one author evaluated the suture in the front view [26].

The assessment of the risk of bias in the included studies is presented in Table 4. Of the ten studies included in this review, one was classified as “good” [26], indicating a low risk of bias, eight studies were classified as “fair” [15,16,23,24,25,27,28,29], indicating a moderate risk of bias, and one article was rated “poor”, presenting a high risk of bias [13].

Table 4.

Assessment of the risk of bias in the included studies.

Among the ten articles selected, seven studies did not report clear eligibility criteria [13,15,16,23,24,25,28], and in the 10 included articles, it was not possible to determine whether all eligible participants who met the pre-specified entry criteria were included. Four authors described sample calculations or analyses of the power of the study a posteriori [25,26,27,28], and one study had a sample of more than 50 participants [29].

3.3. Meta-Analysis

Five articles [15,23,25,27,28] were included in the meta-analysis because they presented comparable data. The corresponding authors of the articles were contacted twice by e-mail for clarification or provision of additional data.

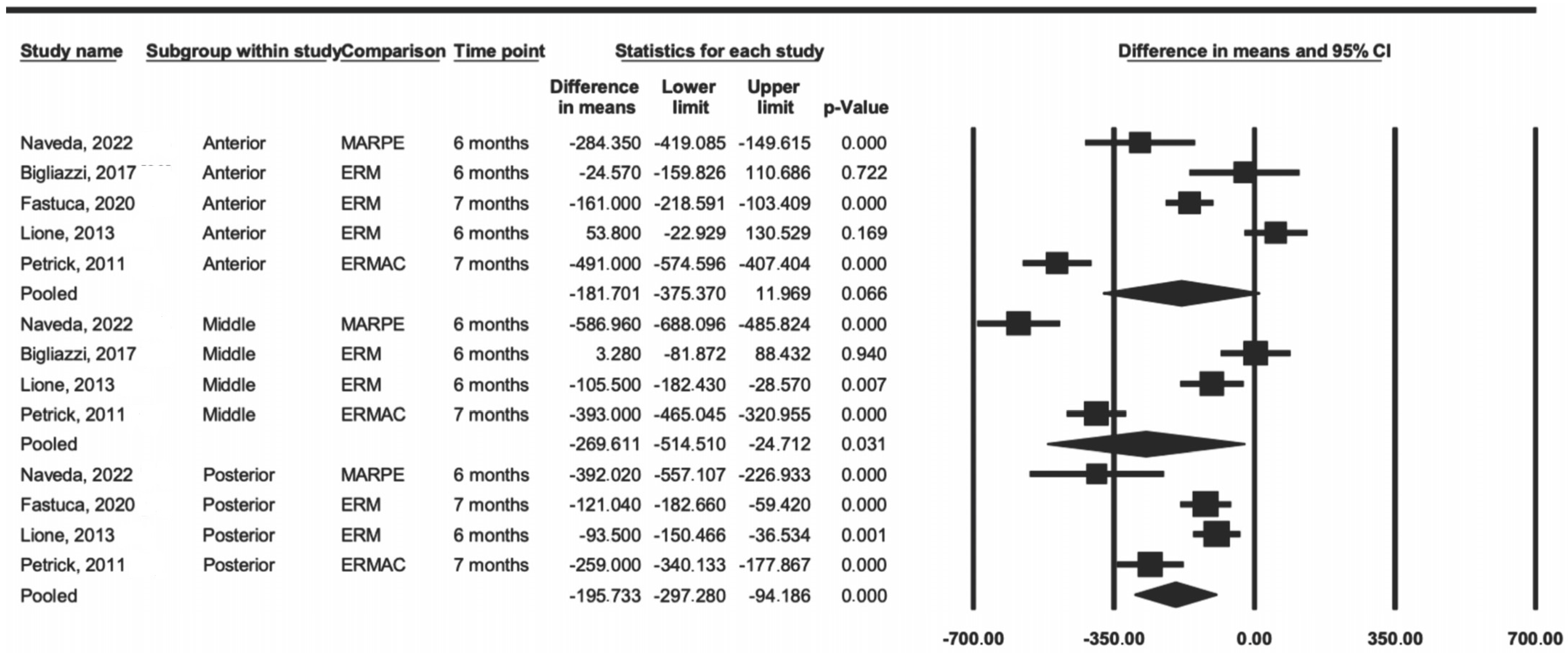

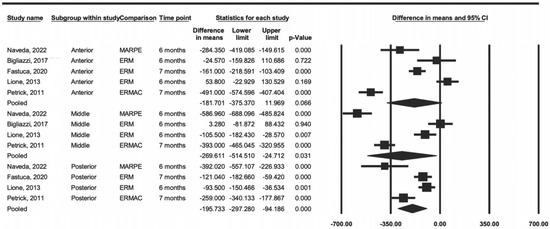

Initially, a comparison was made considering the anterior, middle, and posterior regions as subgroups, according to the anatomical limits used by the authors to divide the regions evaluated. In the meta-analysis of the anterior region, it was possible to include five articles, three of which were about RME, one was about SARPE, and one was about MARPE. In the middle and posterior regions, it was possible to include four studies, two of which were about RME, one was about SARPE, and one was about MARPE.

The heterogeneity result, represented by the I2 index, in the anterior region was 95%, in the middle region was 97%, and in the posterior region was 84%, thus being considered as having a high level of heterogeneity.

The meta-analysis results by region were significantly present in two regions, the middle (p = 0.031) and posterior (p < 0.001), whereas the anterior region showed no difference (p = 0.06) (Figure 2). The data showed that RME tended to have less difference in density when compared to that of SARPE and MARPE in all evaluated regions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the average difference by region (anterior, middle, and posterior) [15,23,25,27,28].

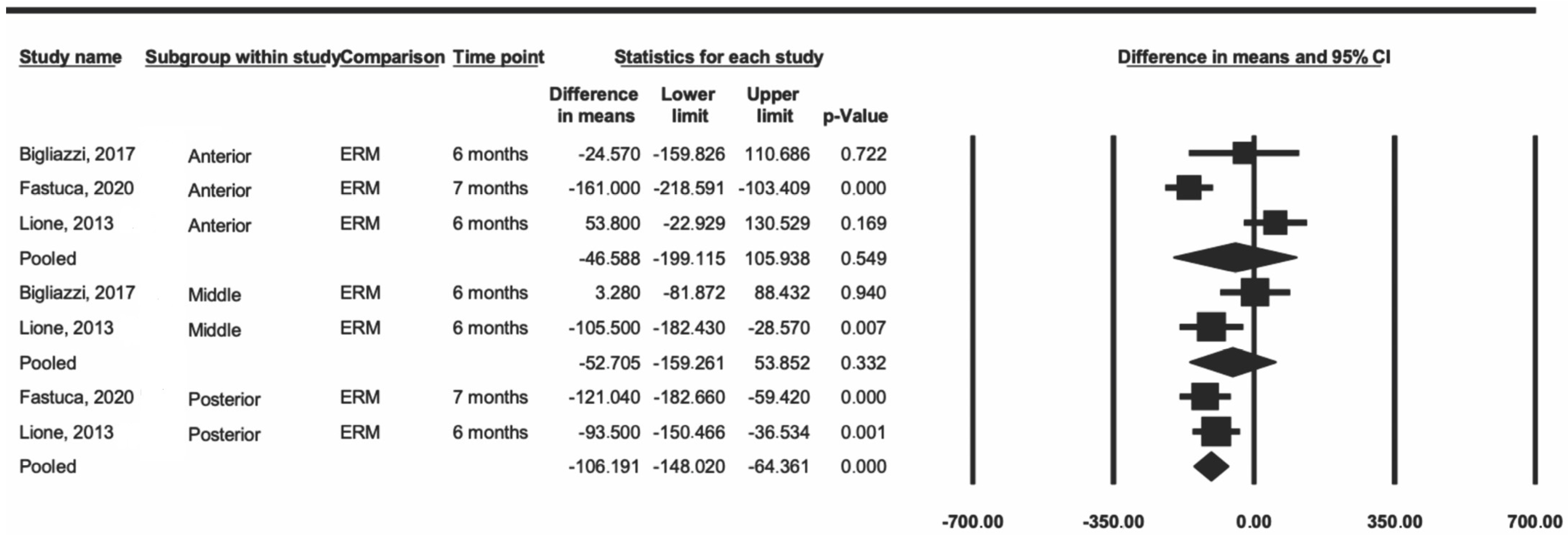

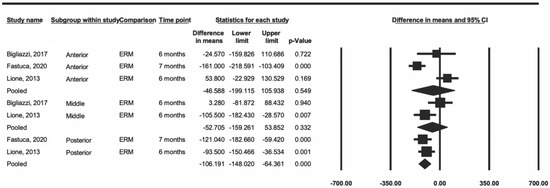

Subsequently, a sensitivity analysis was performed including only the articles that used RME [23,24,28]. The data showed a decrease in heterogeneity for the anterior and middle regions (I2 = 89% and 71%, respectively), and the posterior heterogeneity was minimal (I2 = 0.0%) (Figure 3). In this same analysis, the difference remained significant only in the posterior region (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the average difference for ERM [23,25,28].

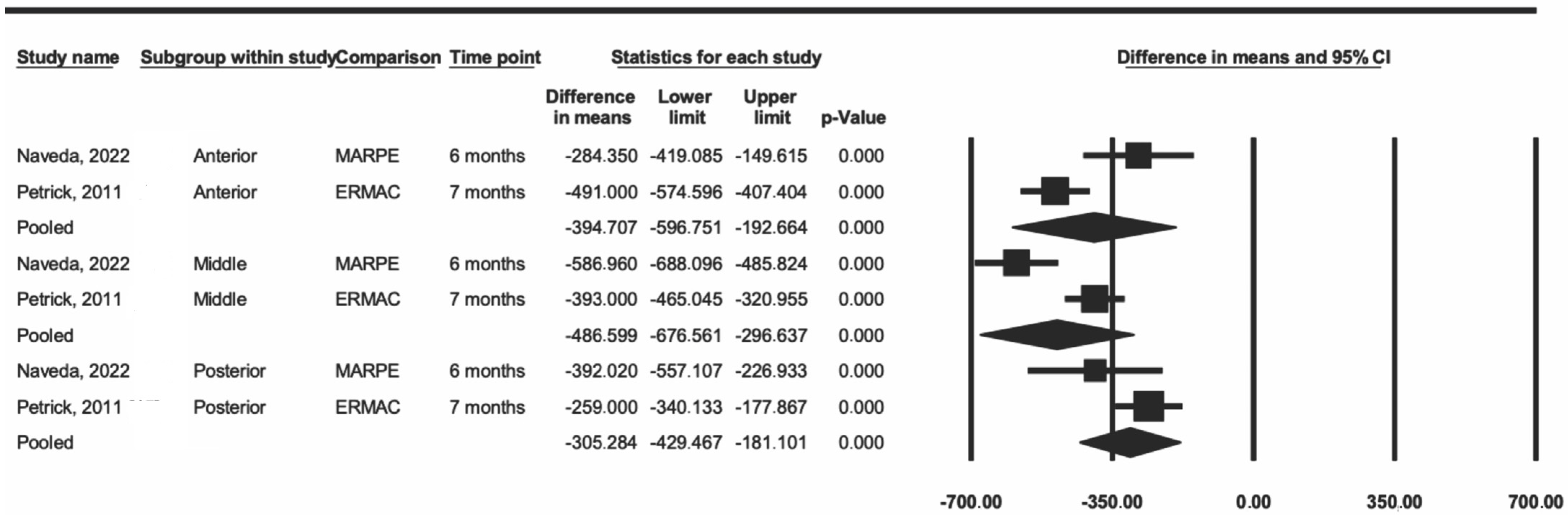

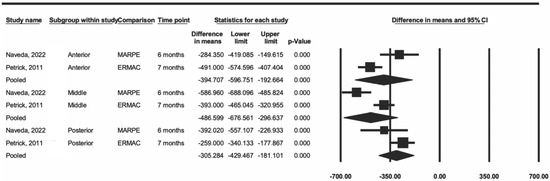

Another sensitivity analysis included two articles that used MARPE and SARPE [13,27]. The data showed a decrease in heterogeneity in the three regions (I2 = 84% in the anterior region, 89% in the middle region, and 50% in the posterior region) when compared to the values from the first analysis. The difference was statistically significant for the three regions (p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the average difference between ERMAC and MARPE [15,27].

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

In the present systematic review, articles that evaluated RME, SARPE, and/or MARPE by CT in the treatment of maxillary deficiency were included. The CT images were analyzed using Hounsfield units (HU), which is the most current method to determine bone density and has been used by dentists to quantify the structure and quality of maxillary and mandibular bone [30,31].

The five articles included in the meta-analysis measured bone density in different areas of the MPS [15,23,25,27,28]. Despite variations in the articles’ way of measuring, the presented measures were grouped into the anterior, middle, and posterior regions. In the anterior region, it was possible to include five articles, of which three were about RME [23,25,28], one was about SARPE [15], and one was about MARPE [27]. In the middle and posterior regions, it was possible to include four studies, two of which were about RME [23,28], one was about SARPE [15], and one was about MARPE [27]. The variation in the way that the measurement is performed and the fact that they are different procedures with different effects on bone density after expansion may be contributing factors to the high values found for heterogeneity, even after our sensitivity analyses.

The posterior region showed a significant decrease in suture density, regardless of the procedure, and minimal heterogeneity in cases in which only RME studies were used [23,25,28] and moderate heterogeneity in cases in which SARPE and MARPE were used [15,27]. These data suggest that, for the posterior region, a longer retention time is needed so that the bone density after expansion is close to the initial value. The results of three studies [16,24,26] included in the review—and not in the meta-analysis—corroborate that (a) 6 months after RME [24] and (b) 6 to 7 months after SARPE [16,26], the bone density of the posterior region had not yet reached the baseline level.

In the anterior and middle regions, from the meta-analysis results, there is no evidence to state that the density of the palatine suture is different 6 months after RME. A study included in the review and not in the meta-analysis found a similar result: 6 months after expansion with RME, there no significant changes reported [13]. Similarly, a study based on the tomographic evaluation of 17 children aged 5 to 10 years showed a completely ossified suture after 8 to 9 months of retention [32].

Although only one SARPE study was included in the meta-analysis [15], three articles were included in the review and all showed decreased suture density [15,16,26]; among these, the greatest differences in density were found in the anterior and middle regions. Only one study that evaluated MPS density after MARPE was included in the review and meta-analysis [27]; its results showed a greater decrease in bone density in the median region and in the midline. These differences between the results for SARPE and MARPE may be related to the injuries caused by the use of the chisel in the anterior region of the palate during the SARPE procedure [27] and also the mini-implants’ location in cases of MARPE, which is usually in the middle portion of the palate, where consequently there will be a greater concentration of force during the active phase [27,33], negatively influencing bone repair.

According to the data presented in the meta-analysis, RME tended to have less of a difference in bone density than SARPE and MARPE. The literature reports that bone repair has been associated with the initial age of the patient when performing an expansion [34]; taking into account that SARPE and MARPE are treatment alternatives for adult patients with no growth potential, the age of the patients can then be a possible response for this difference. These data can also impact the retention time; the literature reports that the retention period after expansion ranges from 2 to 12 months [35]. All studies included in this meta-analysis evaluated suture density up to 6 [21,25,26] or 7 months [16,25] after expansion. Despite being a plausible period for suture reorganization in cases of RME [13,15], this time may not be sufficient for patients treated with SARPE and MARPE. Density values show that 7 months after SARPE, remineralization was still incomplete and it was questionable whether the ossification present up until that point would be able to resist the forces exerted by adjacent bone structures and whether recurrence could be avoided [15,16].

The MPS fusion first occurs posteriorly and then progresses anteriorly with new bone formation. For this reason, the opening of the suture takes place in the form of a triangle with the base located in the anterior part of the maxilla and the expansion occurring predominantly in the anterior and middle regions [29]. The bone density in the posterior region examined via occlusal radiographs was reported to decrease more than in the anterior region [35], similar to our results. It is reasonable to assume that after RME or SARPE, the density of the maxillary suture may differ depending on the level of bone density prior to expansion, which, according to the Misch classification, would be D3 (350 to 850 Hounsfield units) [36]. Specifically, if the posterior part of the maxilla has already undergone ossification, then the suture density in this region is likely to be higher after expansion compared to the anterior and middle regions, where the lower pre-expansion density may result in little to no difference in suture density. More studies are needed to prove this theory and a longer period of anterior retention may be recommended to prevent relapses.

4.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

In our analysis, the risk of bias was assessed using a tool specifically designed for before-and-after studies. It is important to underscore that the methodological quality that labeled the reviewed articles as “good” or “fair” applies specifically to the context of before-and-after studies. Compared to randomized clinical trials and controlled clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard for systematic reviews, the risk of bias is higher. Ethical considerations preclude randomization in choosing between treatments such as RME, SARPE, or MARPE, as each patient should receive the most effective available surgical option. Additionally, the nature of these treatments makes blinding participants impractical [21].

4.3. Limitations

Ten non-randomized clinical studies were included in this review, which can be considered as a limitation of this review. Furthermore, some of the studies did not report enough data, such as the statistical tests used, the p-values, the standard deviation, or whether the sample size was sufficient, indicating the need for better studies on the subject.

5. Conclusions

There is not enough evidence to say that suture density is different after 6 months of RME in the anterior and middle regions; bone density values for SARPE and MARPE suggest that 6 or 7 months after expansion, the bone density is still not similar to the initial one in the three regions. More studies are needed to evaluate the density behavior in the posterior region of the midpalatal suture and to directly compare the differences in suture density between RME, SARPE, and MARPE.

These results should be interpreted with caution due to the number of trials included and the difficulty of methodological standardization, which may affect the risk of bias. Future studies with long-term follow-ups, paired control groups, and standard methodologies are needed for clinical recommendations based on evidence with predictable results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.F., C.T.M. and J.d.A.C.-M.; methodology, L.M.F., D.M.C.B., N.C.V. and C.O.L.; software, A.d.A.C.-S.; validation, C.T.M., C.F.M. and J.d.A.C.-M.; formal analysis, C.T.M. and J.d.A.C.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.F., D.M.C.B., N.C.V. and J.d.A.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, C.T.M., C.F.M. and J.d.A.C.-M.; visualization, A.d.A.C.-S. and C.T.M.; supervision, C.F.M., C.T.M. and J.d.A.C.-M.; resources, C.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.W., Jr. Contemporary Orthodontics, 5th ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2012; p. 768. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, F.; Liu, S.; Lei, L.; Liu, O.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Q.; Lu, Y. Changes of the upper airway and bone in microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion: A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) study. J. X-ray Sci. Technol. 2020, 28, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, M.; Thilander, B. Palatal suture closure in man from 15 to 35 years of age. Am. J. Orthod. 1977, 72, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.M., Jr. Sutural biology and the correlates of craniosynostosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993, 47, 581–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungcharassaeng, K.; Caruso, J.M.; Kan, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Taylor, G. Factors affecting buccal bone changes of maxillary posterior teeth after rapid maxillary expansion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 132, 428.e1–428.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prévé, S.; García Alcázar, B. Interest of miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion on the upper airway in growing patients: A systematic review. Int. Orthod. 2022, 20, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunheid, C.; Larson, C.E.; Larson, B.E. Midpalatal suture density ratio: A novel predictor of skeletal response to rapid maxillary expansion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrbein, H.; Yildizhan, F. The mid-palatal suture in young adults. A radiological-histological investigation. Eur. J. Orthod. 2001, 23, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, L.S. Radiographic evaluation of skeletal maturation. A clinically oriented method based on hand-wrist films. Angle Orthod. 1982, 52, 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Baccetti, T.; Franchi, L.; Cameron, C.G.; McNamara, J.A., Jr. Treatment timing for rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2001, 71, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Angelieri, F.; Cevidanes, L.H.; Franchi, L.; Goncalves, J.R.; Benavides, E.; McNamara, J.A., Jr. Midpalatal suture maturation: Classification method for individual assessment before rapid maxillary expansion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 144, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudstaal, M.J.; Poort, L.J.; Van der Wal, K.G.; Wolvius, E.B.; Prahl-Andersen, B.; Schulten, A.J. Surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARME): A review of the literature. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. 2005, 34, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, L.; Baccetti, T.; Lione, R.; Fanucci, E.; Cozza, P. Modifications of midpalatal sutural density induced by rapid maxillary expansion: A low-dose computed- tomography evaluation. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 137, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleall, J.F.; Bayne, D.I.; Posen, J.M.; Subtelny, J.D. Expansion of the midpalatal suture in the monkey. Angle Orthod. 1965, 35, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petrick, S.; Hothan, T.; Hietschold, V.; Schneider, M.; Harzer, W.; Tausche, E. Bone density of the midpalatal suture 7 months after surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion in adults. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, S109–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgueiro, D.G.; Rodrigues, V.H.; Tieghi Neto, V.; Menezes, C.C.; Gonçales, E.S.; Ferreira Júnior, O. Evaluation of opening pattern and bone neoformation at median palatal suture area in patients submitted to surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARME) through cone beam computed tomography. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, J.H.; Pabari, S. Cone beam computed tomography—Current understanding and evidence for its orthodontic applications? J. Orthod. 2013, 40, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahl, B.; Fischbach, R.; Gerlach, K.L. Temporomandibular joint. Morphology in children after treatment of condylar fractures with functional appliance therapy: A follow-up study using spiral computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 1995, 24, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, T.; Zou, W. Effects of rapid maxillary expansion on the midpalatal suture: A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louro, R.S.; Calasans-Maia, J.A.; Mattos, C.T.; Masterson, D.; Calasans-Maia, M.D.; Maia, L.C. Three-dimensional changes to the upper airway after maxillomandibular advancement with counterclockwise rotation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, C.O.; Martins, M.M.; Ruellas, A.C.O.; Ferreira, D.M.T.P.; Maia, L.C.; Mattos, C.T. Soft tissue assessment before and after mandibular advancement or setback surgery using three-dimensional images: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigliazzi, R.; Magalhães, A.D.O.S.; Magalhães, P.E.; de Magalhães Bertoz, A.P.; Faltin, K., Jr.; Arita, E.S.; Bertoz, F.A. Cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of bone density of midpalatal suture before, after, and during retention of rapid maxillary expansion in growing patients. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2017, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schauseil, M.; Ludwig, B.; Zorkun, B.; Hellak, A.; Korbmacher-Steiner, H. Density of the midpalatal suture after RME treatment—A retrospective comparative low-dose CT-study. Head Face Med. 2014, 20, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastuca, R.; Michelotti, A.; Nucera, R.; D’Antò, V.; Militi, A.; Logiudice, A.; Caprioglio, A.; Portelli, M. Midpalatal Suture Density Evaluation after Rapid and Slow Maxillary Expansion with a Low-Dose CT Protocol: A Retrospective Study. Medicina 2020, 56, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, D.; Carvalho, P.H.A.; Dos Santos, J.C.; Wagner, F.; Gabrielli, M.A.C.; Gabrielli, M.F.R.; Filho, V.A.P. Bone formation after surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion: Comparison of 2 distraction osteogenesis protocols. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2022, 133, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveda, R.; Dos Santos, A.M.; Seminario, M.P.; Miranda, F.; Janson, G.; Garib, D. Midpalatal suture bone repair after miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion in adults. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lione, R.; Franchi, L.; Fanucci, E.; Laganà, G.; Cozza, P. Three-dimensional densitometric analysis of maxillary sutural changes induced by rapid maxillary expansion. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2013, 42, 71798010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatu, R.; Nagib, R.; Dincă, M.; Vâlceanu, A.S.; Szuhanek, C.A. Midpalatal suture morphology and bone density evaluation after orthodontic expansion: A cone-bean computed tomography study in correlation with aesthetic parameters. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 803–809. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Kwon, T.G. Density of the alveolar and basal bones of the maxilla and the mandible. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.R.; Gamble, C. Bone classification: An objective scale of bone density using the computerized tomography scan. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2001, 12, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Filho, O.G.; Lara, T.S.; da Silva, H.C.; Bertoz, F.A. Post expansion evaluation of the midpalatal suture in children submitted to rapid palatal expansion: A CT study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2006, 31, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, E.H.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Yu, H.S.; Park, Y.C.; Lee, K.J. Evaluation of the effects of miniscrew incorporation in palatal expanders for young adults using finite element analysis. Korean J. Orthod. 2018, 48, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczewski, P.; Shadi, M. Factors influencing bone regenerate healing in distraction osteogenesis. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2013, 15, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sannomiya, E.K.; Macedo, M.M.; Siqueira, D.F.; Goldenberg, F.C.; Bommarito, S. Evaluation of optical density of the midpalatal suture 3 months after surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2007, 36, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misch, C.E. Bone character: Second vital implant criterion. Dent. Today 1988, 7, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).