Abstract

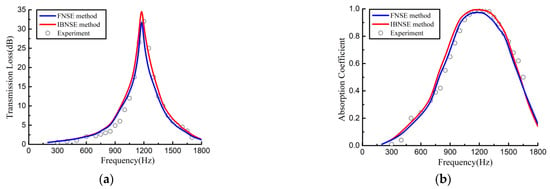

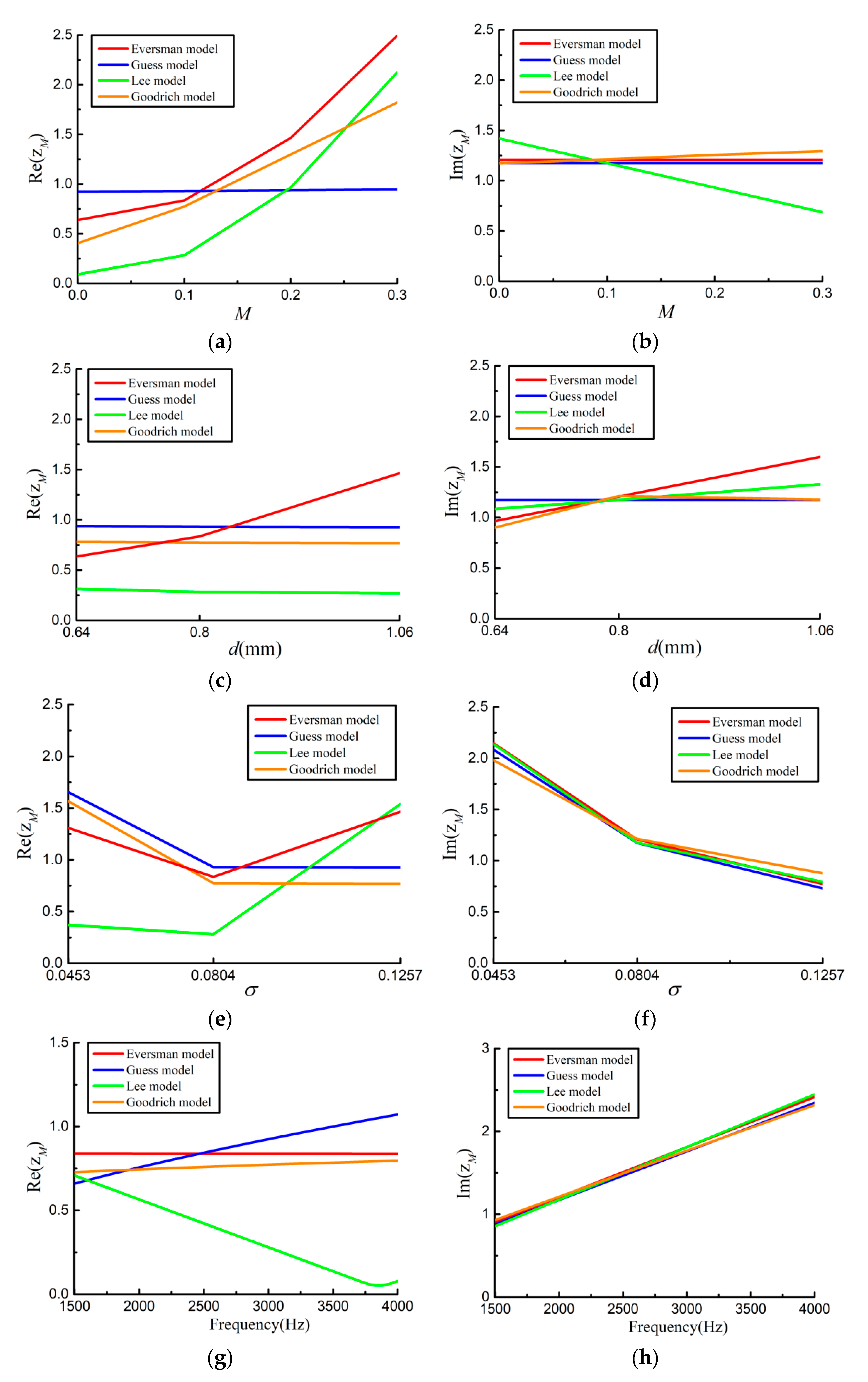

In this paper, planar and the cylindrical broadband non-uniform acoustic absorbers were constructed, both of which use broadband absorption units (BAUs) as their building blocks. The impedance boundary Navier–Stokes equation (IBNSE) method was developed to predict the absorption characteristics of the lined duct with non-uniform acoustic absorbers, in which each small piece of perforated plate is acoustically equivalent to a semi-empirical impedance model through the boundary condition. A total of four semi-empirical impedance models were compared under different control parameters. The full Navier–Stokes equation (FNSE) method was used to verify the accuracy of these impedance models. It was found that the IBNSE method with the Goodrich model had the highest prediction accuracy. Finally, the planar and the cylindrical non-uniform acoustic absorbers were constructed through spatial extensions of the BAU. The transmission losses and the absorption coefficients of the rectangular duct–planar acoustic absorber (RDPAA) and annular duct–cylindrical acoustic absorber (ADCAA) systems under grazing flow were predicted, respectively. The results demonstrated that the broadband absorption of the designed non-uniform acoustic absorbers was achieved. The developed IBNSE method with Goodrich model was accurate and computationally efficient, and can be used to predict the absorption characteristics of an acoustically treated duct in the presence of grazing flow.

1. Introduction

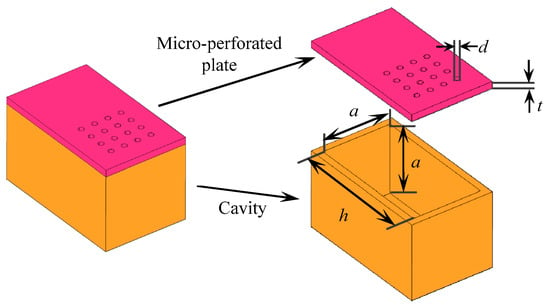

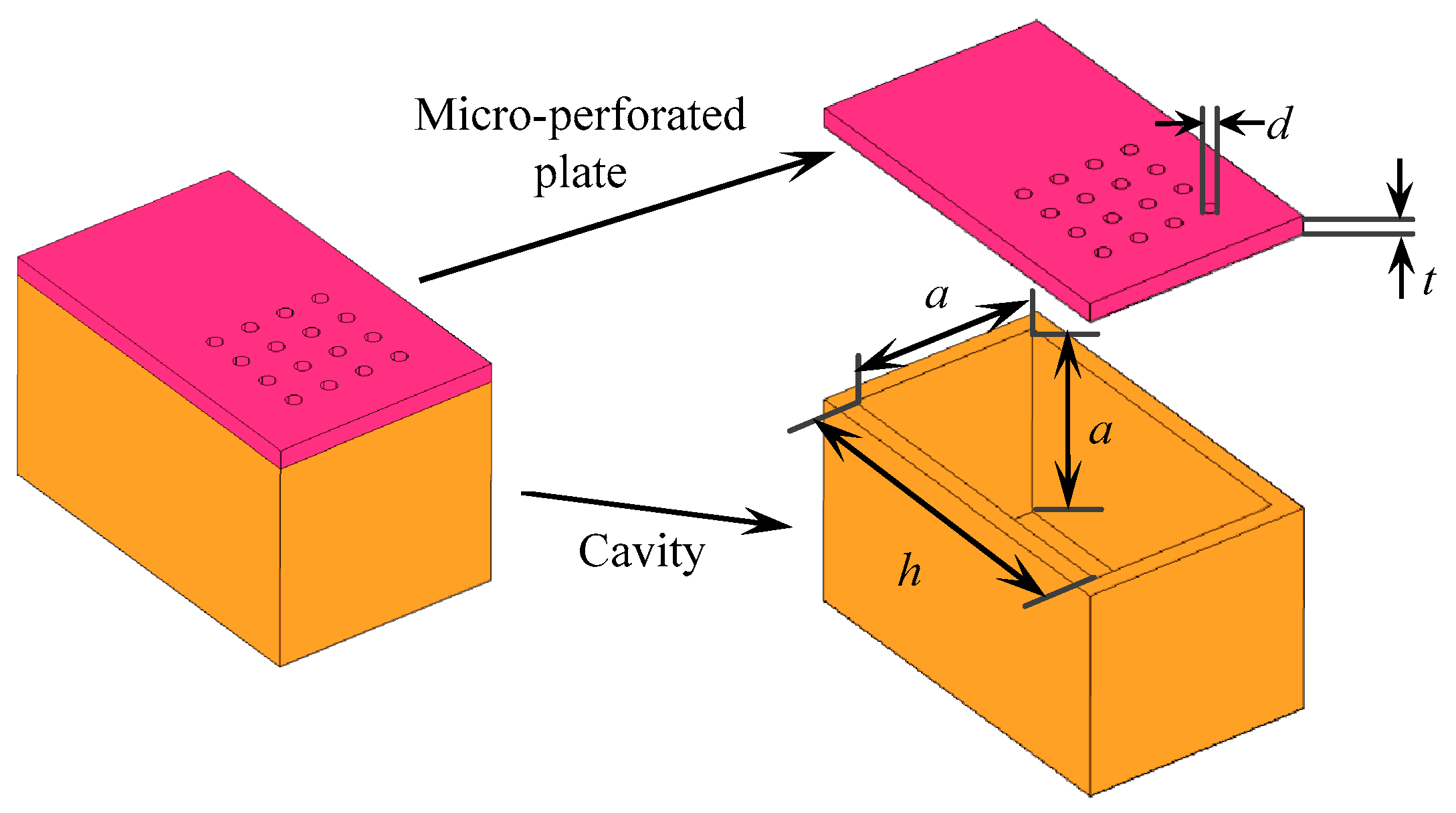

Noise, as one of the main environmental pollutants, is increasingly affecting our daily lives. Attenuating noise pollution through effective control measures has attracted great interest due to stringent noise control regulations. Conventional micro-perforated plate (MPP) absorbers have been widely used to attenuate narrowband noise. Different materials can be selected to cope with the harsh operating conditions, such as high temperature environments. Using the impedance equations proposed by Maa [1], the acoustic absorption characteristics of MPPs can be predicted, and the desired absorption performance can be achieved by choosing the appropriate structural parameters for the MPP absorbers [2,3,4,5].

An absorber with a complex structure by artificial design is called a metamaterial absorber [6]. Based on the metamaterial design, Patel et al. [7] developed a highly efficient, perfect, large angular and ultrawideband solar energy absorber. Ciaburro et al. [8] designed three-layered metamaterial acoustic absorbers based on reused PVC membranes and metal washers. Taking advantage of its sound-absorbing properties, many acoustic absorbers have been developed, such as spatial folding [9,10], Helmholtz resonance [11,12], thin film [13,14] absorbers, etc.

Acoustic absorbers have important applications in the field of acoustic absorption of ducts. The absorber placed in a duct is called an acoustic liner. It is usually composed of a uniform perforated facesheet over a honeycomb cavity and called a single degree of freedom (SDOF) acoustic liner [15], which typically absorbs acoustic energy in a narrow frequency band dictated by the resonance and antiresonance frequencies of the cavities. A double degree of freedom (2DOF) acoustic liner [16] can offer a higher absorption bandwidth and is capable of covering the necessary source spectrum. To obtain an adjustable acoustic absorption performance, Yan [17] designed a 2DOF honeycomb acoustic liner and demonstrated the feasibility of adjustable acoustic absorption by changing the height of the back cavity. Gautam [18] investigated the acoustic performance of a 2DOF Helmholtz resonator and elaborated on the effect of changing the internal dimensions of the resonating cavity on the underlying acoustic attenuation.

Historically, traditional SDOF and 2DOF acoustic liners have been designed for reduction of noise at a fixed frequency. However, there is a high demand for broadband noise reduction in engineering practice. To this end, the energy of dominant source modes can be made to redistribute into higher order modes which are more easily suppressed by the absorber. This modal conditioning technology is generally achieved by non-uniform acoustic absorption structures. In recent years, the non-uniform acoustic absorption structure, characterized by the spatial variations of the impedance, has received extensive attention. Previous studies demonstrated that the optimized absorption structures with spatially varying impedance offer increased attenuation compared to uniform absorption structures. Several investigators have investigated the possibility of improved absorption structure performance by means of modal redistribution by incorporating a circumferentially or axially segmented absorption structure into the duct. Watson [19] evaluated the acoustic performances of circumferentially segmented duct absorption structures for a range of frequencies and source structures, and concluded that the circumferentially segmented absorption structure gives better broadband performance than the uniform absorption structure and is not particularly sensitive to changes in modal structure of the source. Brown et al. [20] explored a broadband absorption structure by varying the facesheet porosity and the hole diameter for each individual cavity along the axial direction of the duct, while keeping the facesheet thickness and core depth constant. They found that the mixed arrangement of perforated plates with different parameters could broaden the noise absorption bandwidth. Palani et al. [21] designed a new type of non-uniform acoustic absorber which includes a slanted porous septum concept with varying open areas and a MultiFOCA (Multiple FOlded Cavity Absorber) concept. The results demonstrated that the new structure can improve broadband absorption performance. McAlpine et al. [22] proposed a non-uniform axially segmented liner to attenuate fan noise at high supersonic fan speeds. They found that the acoustic energy was scattered into high radial mode orders, which was better absorbed by the liner. Schiller et al. [23] presented a low drag, axially variable depth acoustic absorption structure containing pairs of resonators coupled together by shared inlet volumes just below the facesheet. This type of absorption structure has the potential to achieve the targeted impedance with fewer openings in the facesheet, and therefore less drag than previous designs.

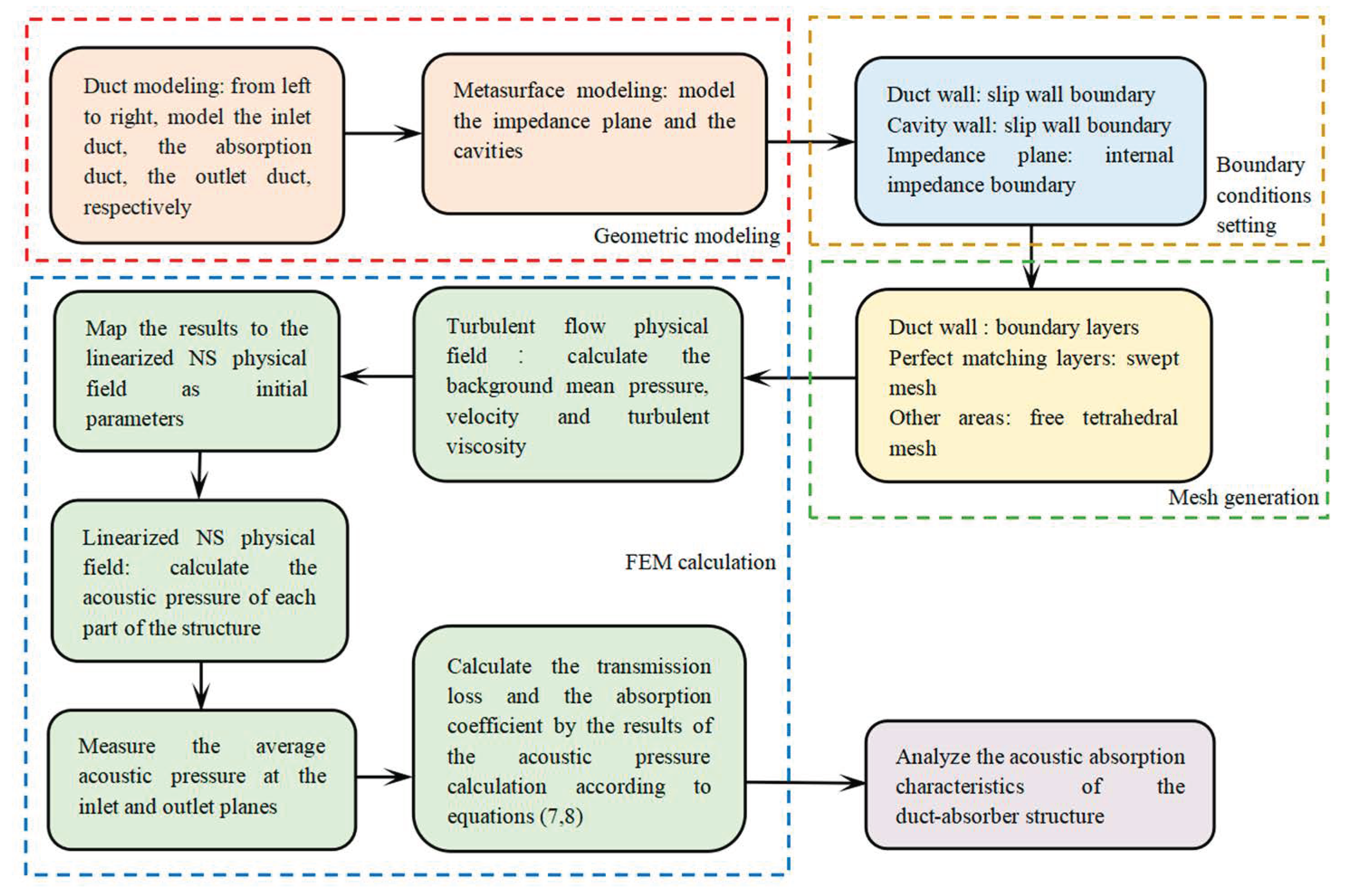

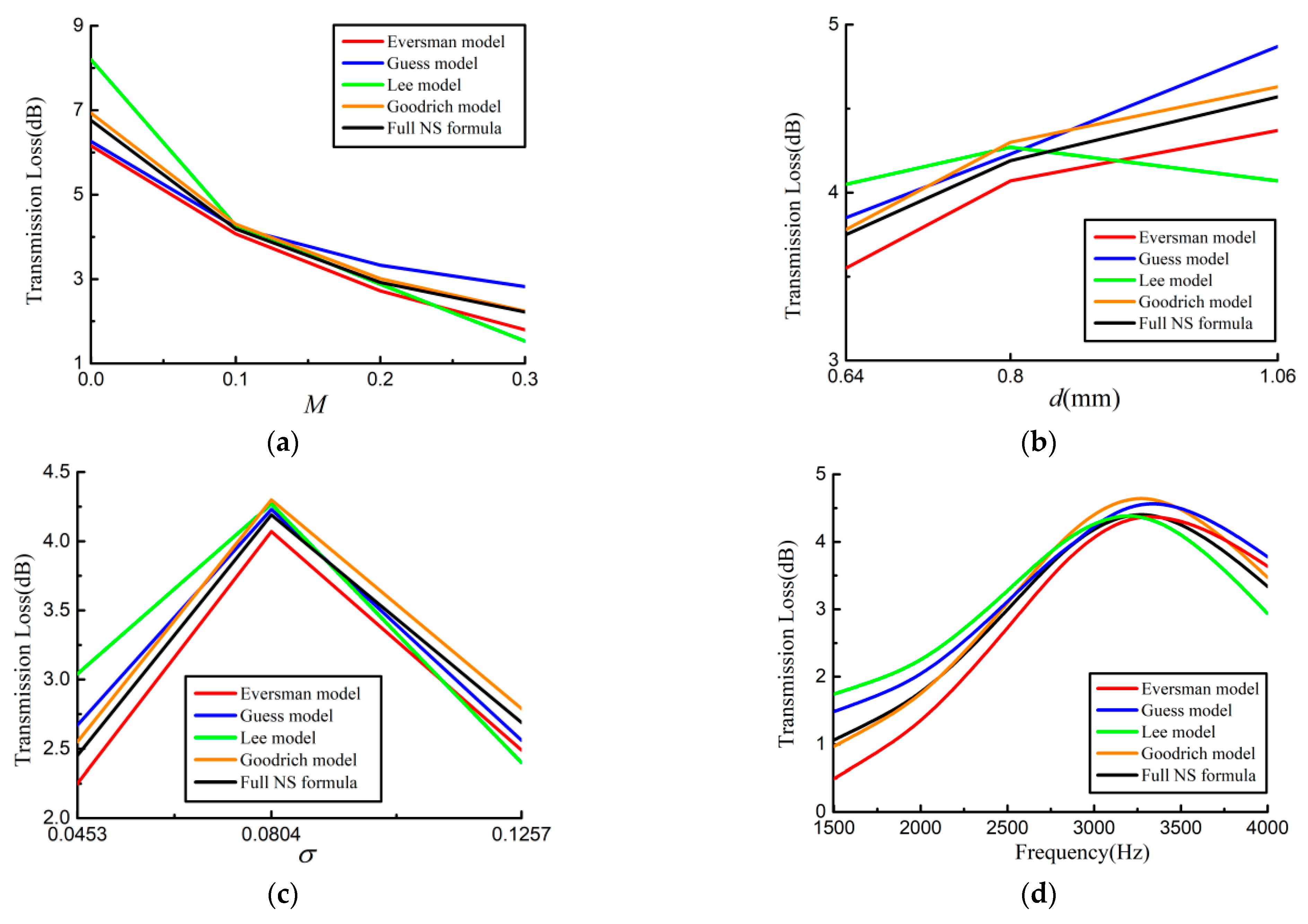

The theoretical analysis methods of the duct with axial [24,25,26] and circumferential non-uniform [27,28,29,30] absorbers have adopted many assumptions and ignored the effects of turbulence and air viscosity, resulting in unreliable predictions in some cases. In view of this, most of the studies on non-uniform acoustic absorbers in ducts were carried out by numerical computation techniques. Schiller et al. [31] compared COMSOL finite element (FE) results of transmission loss of acoustic absorption structure with experimental measurements, and showed that the FE results were highly reliable. Winkler et al. [32] performed an overview of engine liner modeling and a description of the key physical mechanisms. They pointed out that the mid-fidelity tools, such as COMSOL and ACTRAN, are critical enablers for the evaluation and construction of future complex acoustic liners. Scofano et al. [33] used ACTRAN FE code to compute the insertion loss of an acoustic liner for the given duct flow conditions, and identified the need for highly accurate insertion loss modeling. Zhang et al. [34] investigated the response of slit acoustic liners and their impedance properties under incident waves with different intensities and frequencies, as well as with different grazing flow Mach numbers. They developed a fully predictive impedance eduction technique by solving the compressible Navier–Stokes equations with accurate boundary conditions. The use of mid-fidelity tools allows researchers to explore in more detail the physics of the more sophisticated absorber designs. In particular, a high-fidelity method that is based on large eddy simulation (LES) can also be used to capture the local unsteady flow effects inside the perforation holes under acoustic excitation [35,36,37]. Since mid-fidelity as well as high-fidelity approaches are based on a direct resolution of the absorption structure perforations and geometry details in the numerical grid, the computational cost is particularly expensive.

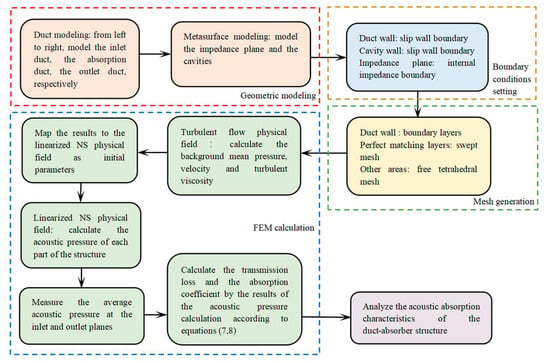

A variable-depth absorber contains chambers with different depths tuned for different frequencies. However, this design will result in a higher structure thickness and lower space utilization [21]. In view of this, this paper first develops a kind of broadband non-uniform acoustic absorber with a thin thickness. The basic building block of the developed absorption structures consists of an MPP and detuned cavities with different volumes. Since the desired cavity volumes in the BAU are mainly realized along the MPP surface, the broadband absorption of the BAU structure can be implemented by a smaller thickness compared with the variable-depth design, and there is no surplus space. The IBNSE method that is based on the semi-empirical Goodrich model, was developed to predict the acoustic absorption characteristics of the duct lined by a non-uniform acoustic absorber at grazing flow condition. The accuracy and the computational efficiency of the developed method were verified by FNSE simulations.

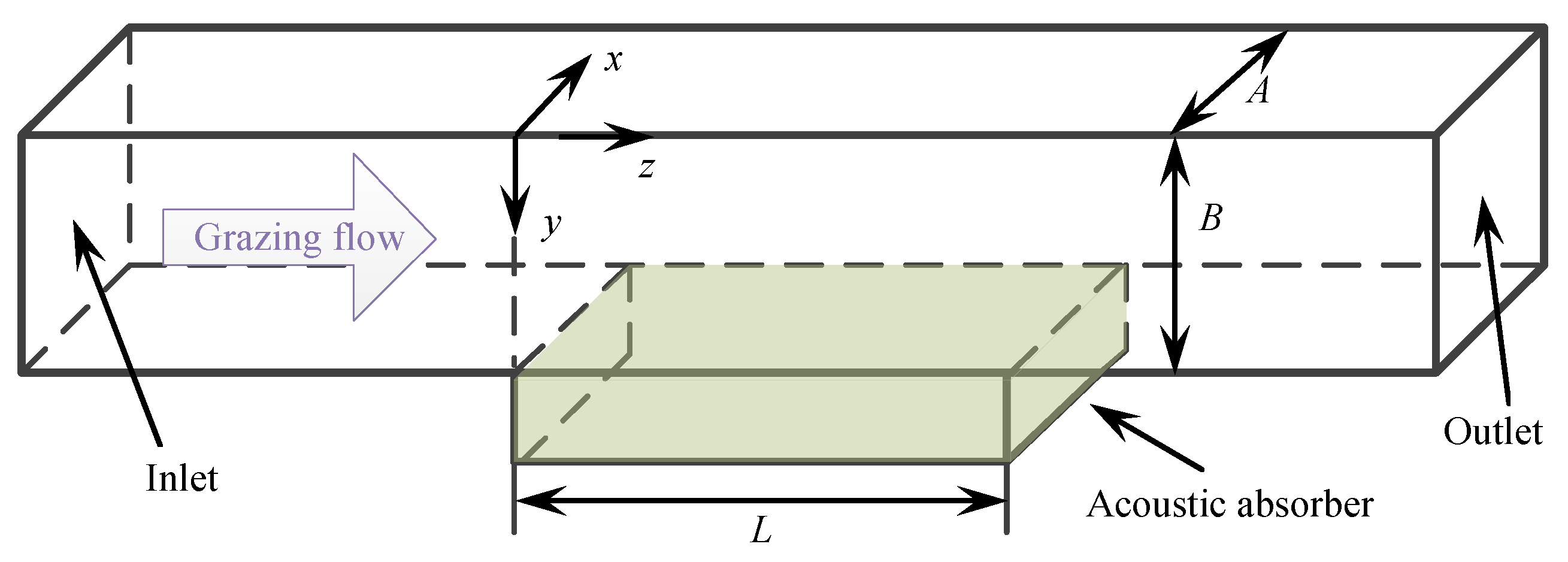

4. Absorption Characteristics of the Duct–Acoustic Absorber System

In this section, a broadband absorption unit (BAU) was constructed. Then, planar and the cylindrical non-uniform acoustic absorbers were formed by extension of the BAU in space. The absorption characteristics of these two absorbers were computed using the developed IBNSE method, in which the Goodrich model was used to obtain the transfer impedance of the lined segments.

4.1. Rectangular Duct Acoustic Absorber

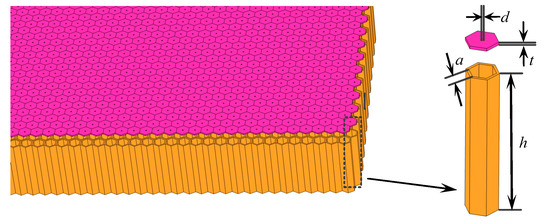

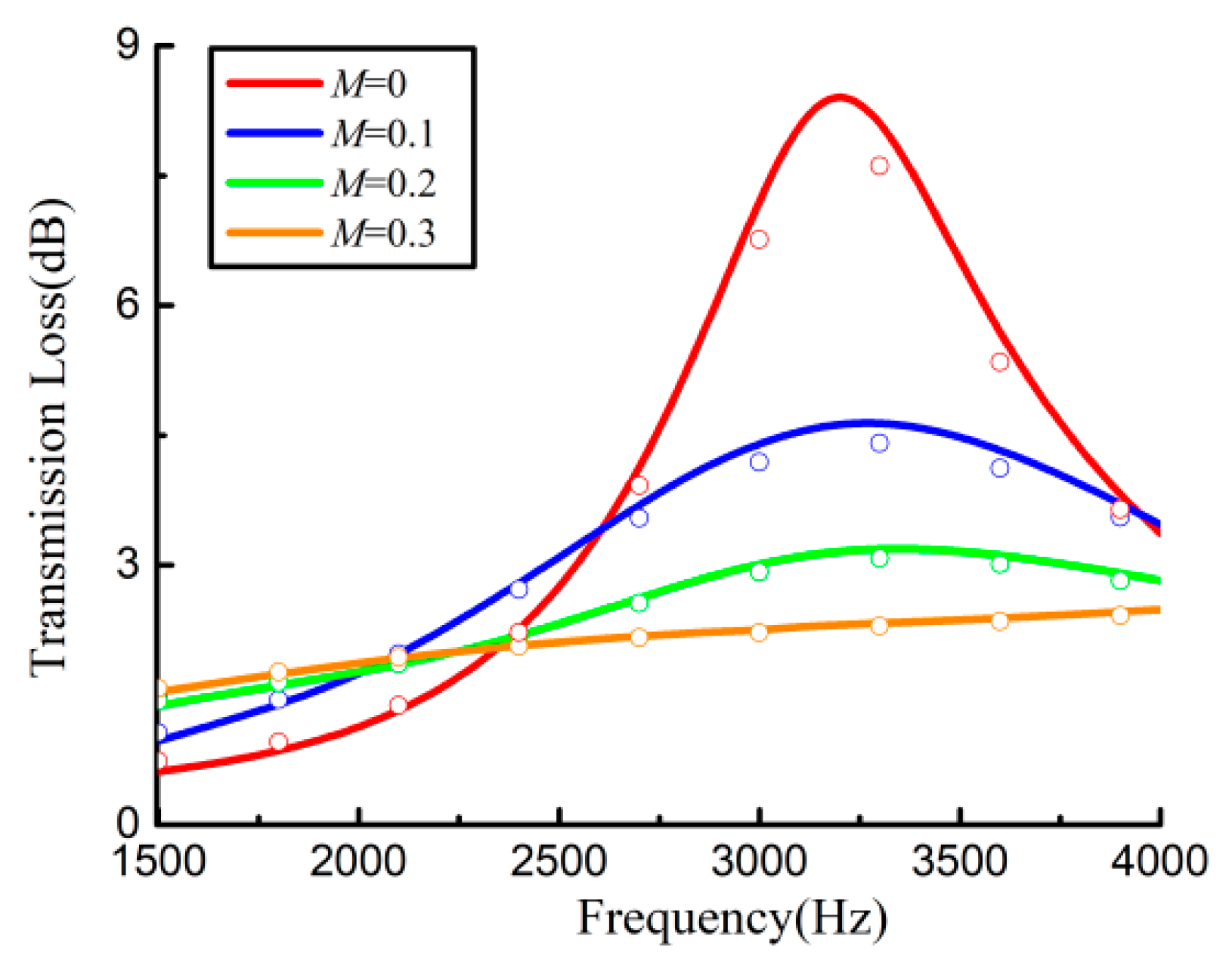

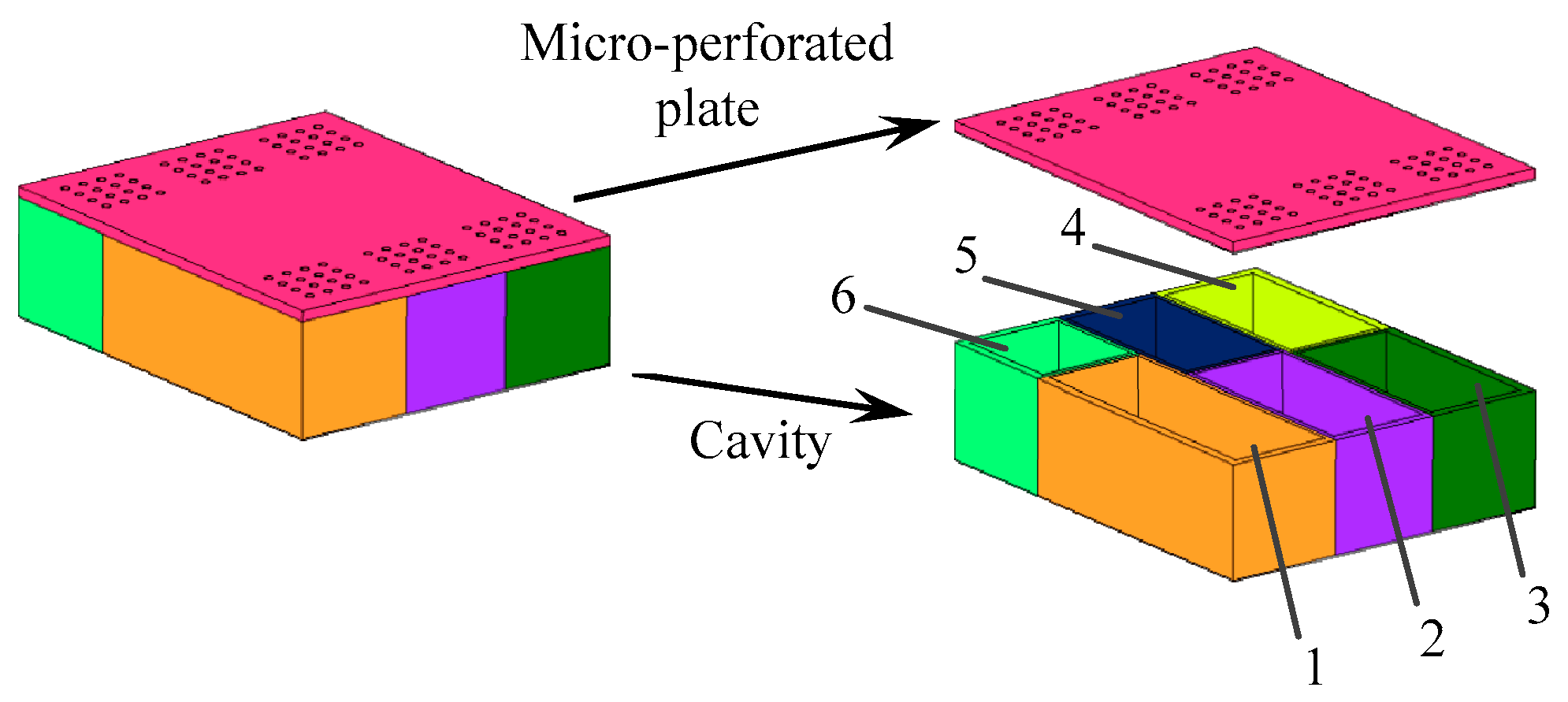

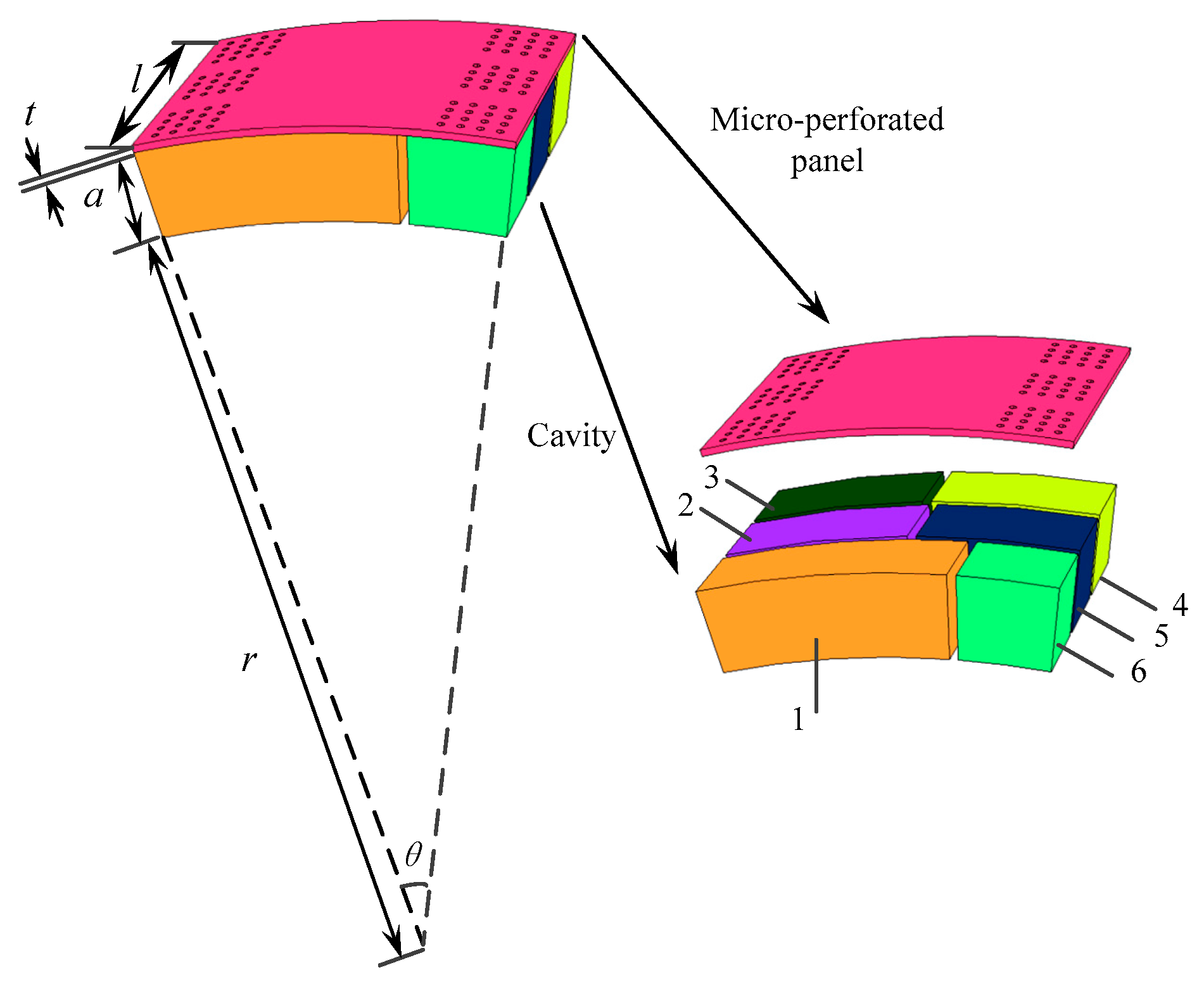

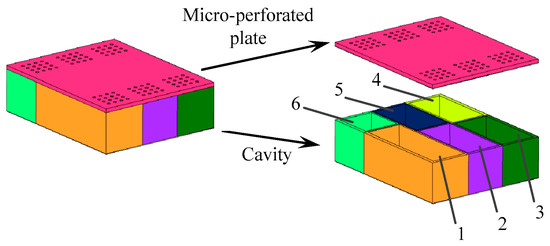

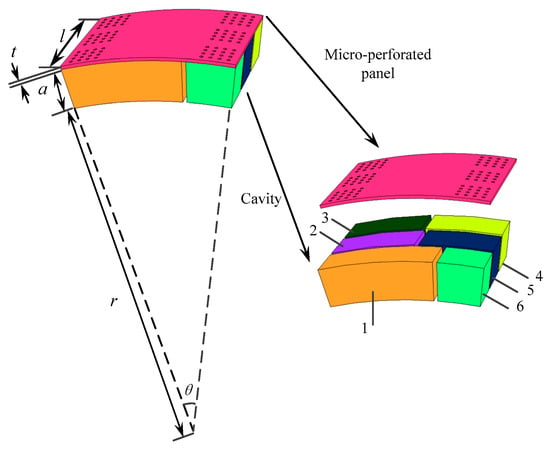

As shown in Figure 4, the cavity length dominated the imaginary part of the overall impedance and hence determined the resonance frequency. Thus, the basic resonant elements with different cavity lengths can be combined together to generate the desired resonance frequency distribution and expand the absorption bandwidth. To this end, a broadband absorption unit (BAU) absorber consisting of six BREs with the same cavity thickness and different cavity lengths was constructed, as shown in Figure 14. The six cavity lengths are , , , , and . They were determined by the maximum average transmission loss of the BAU absorber with a large number of different cavity lengths. The hole diameter and perforation rate were used in the following simulations.

Figure 14.

Schematic view of the planar BAU.

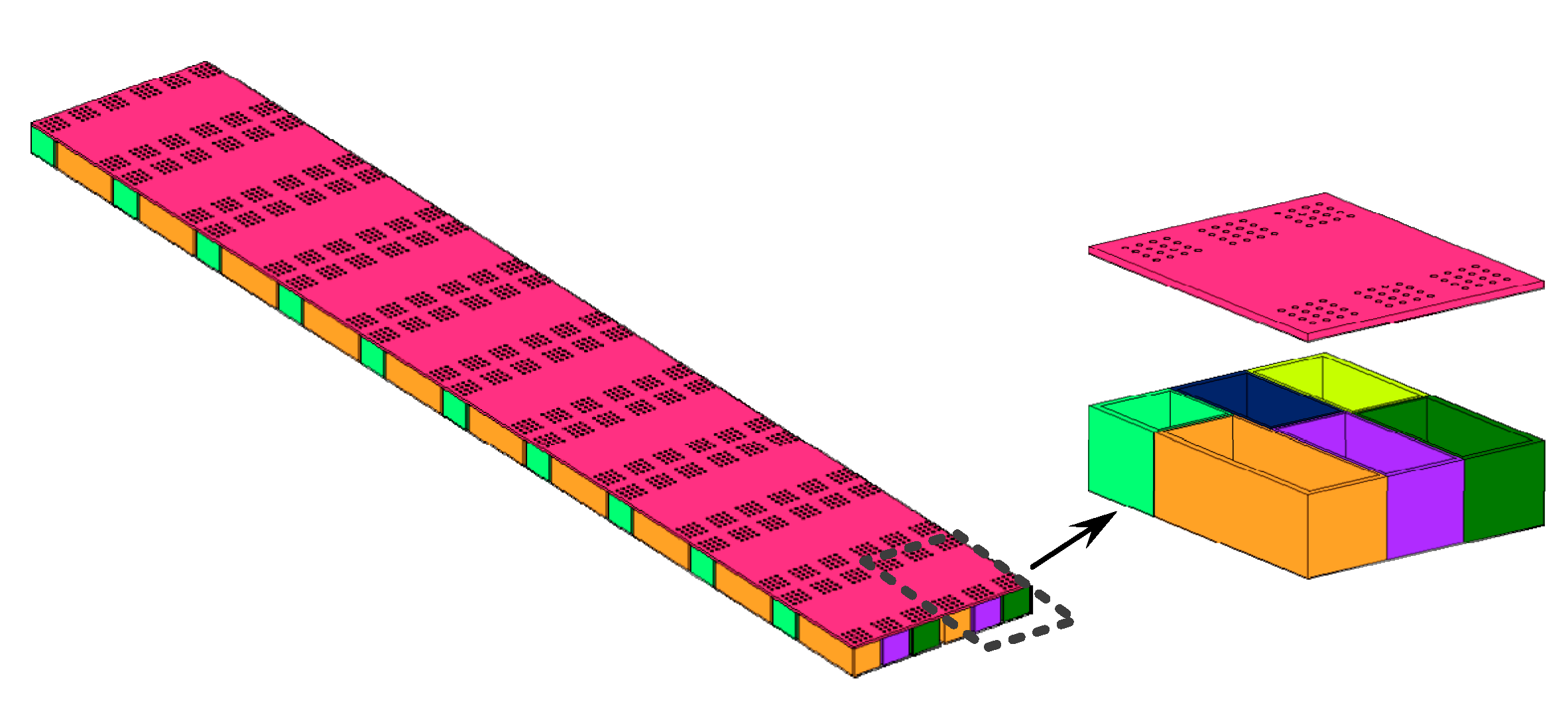

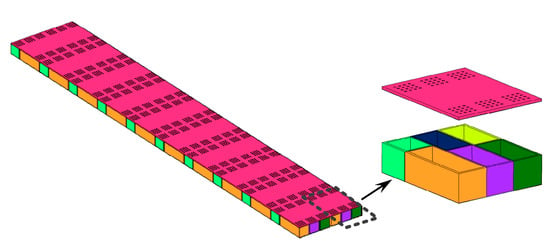

For a practical design of a duct acoustic absorber system, the acoustically treated area in the duct should be large enough, which can be achieved by increasing the number of BAUs. To this end, a planar non-uniform acoustic absorber consisting of 20 BAUs was constructed, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Planar non-uniform acoustic absorber formed by planar BAUs.

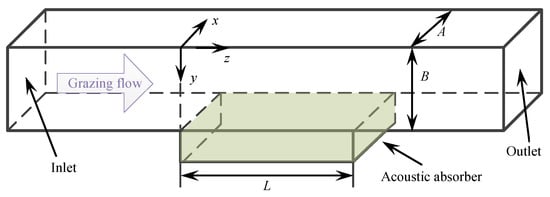

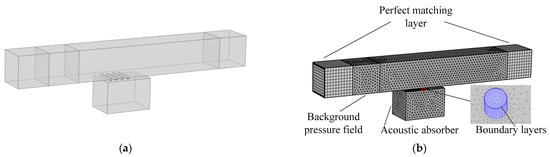

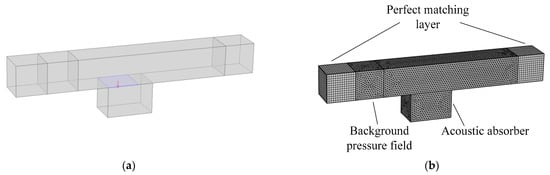

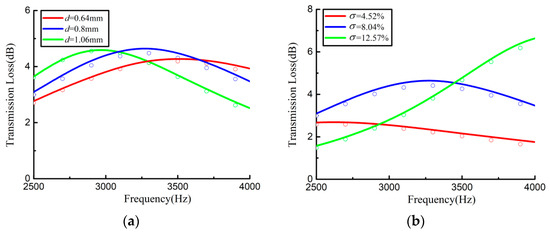

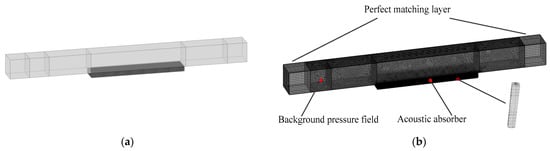

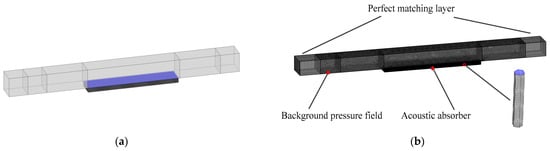

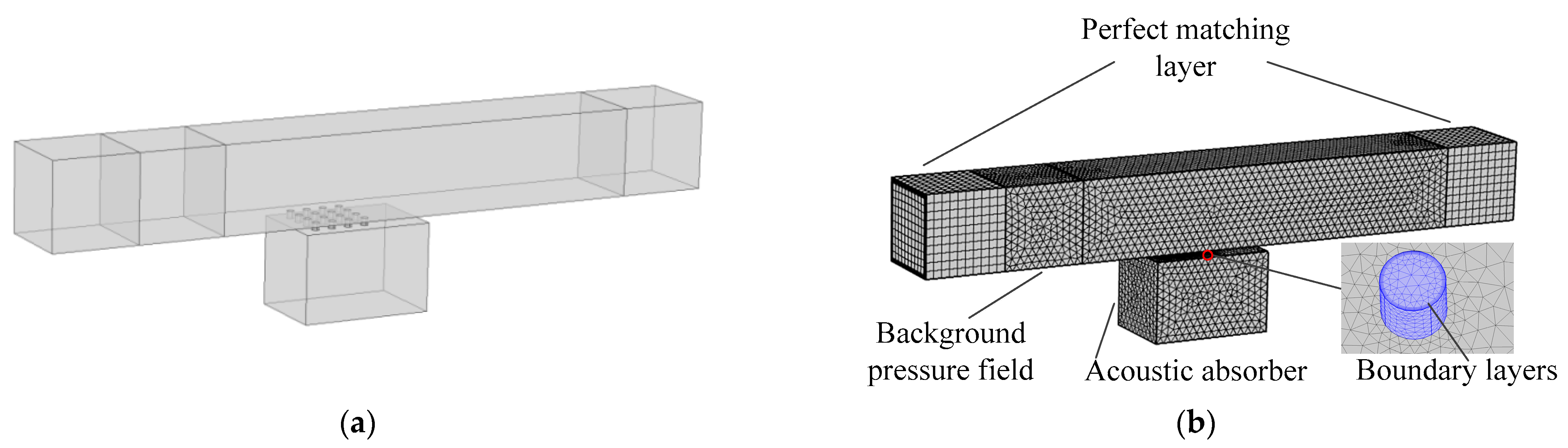

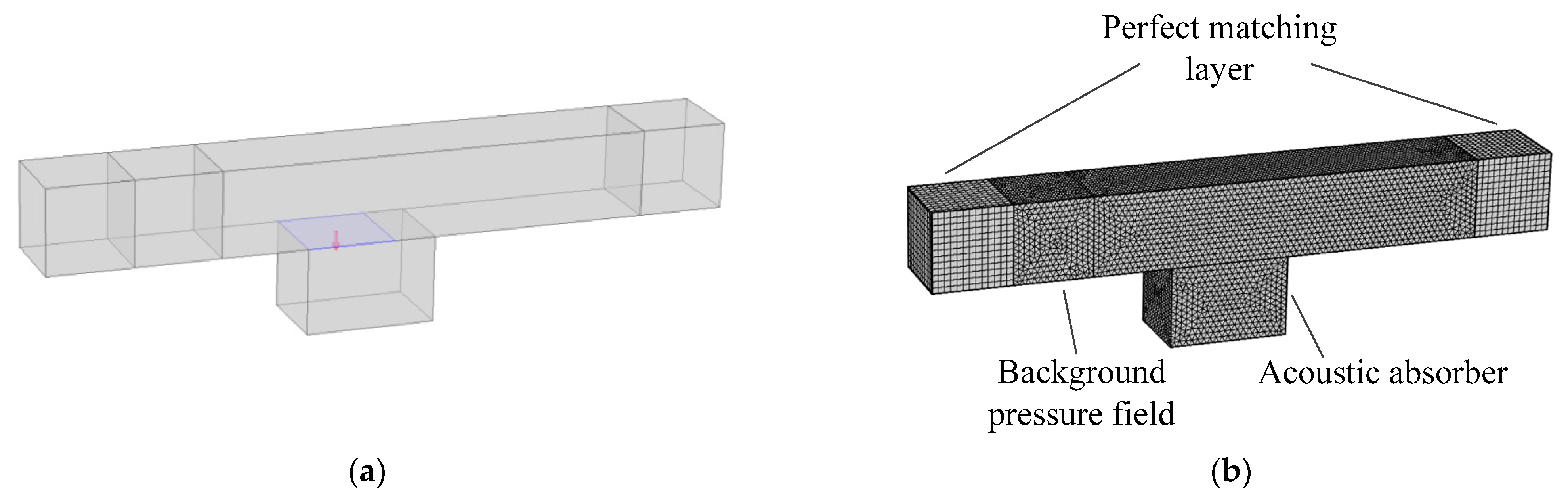

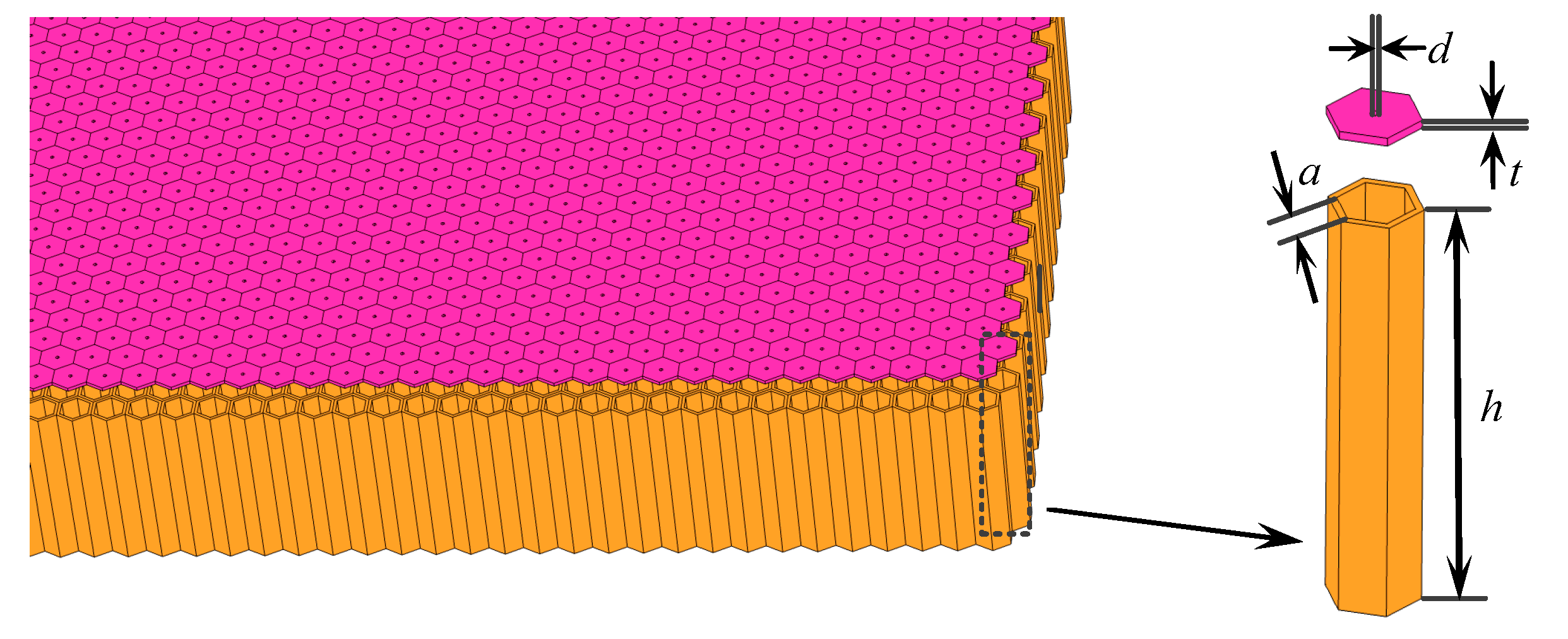

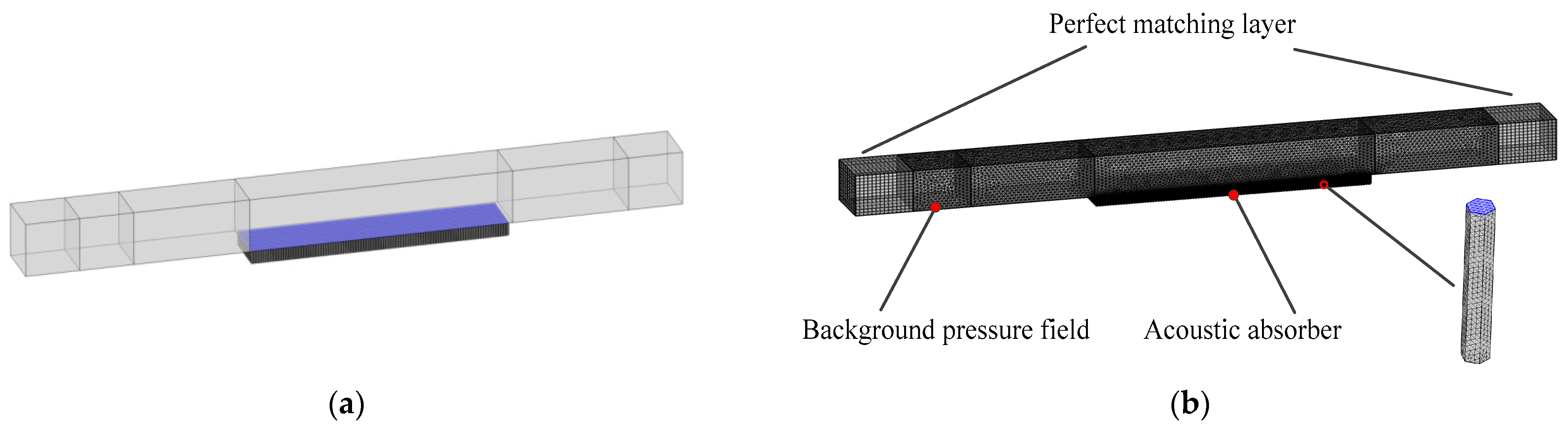

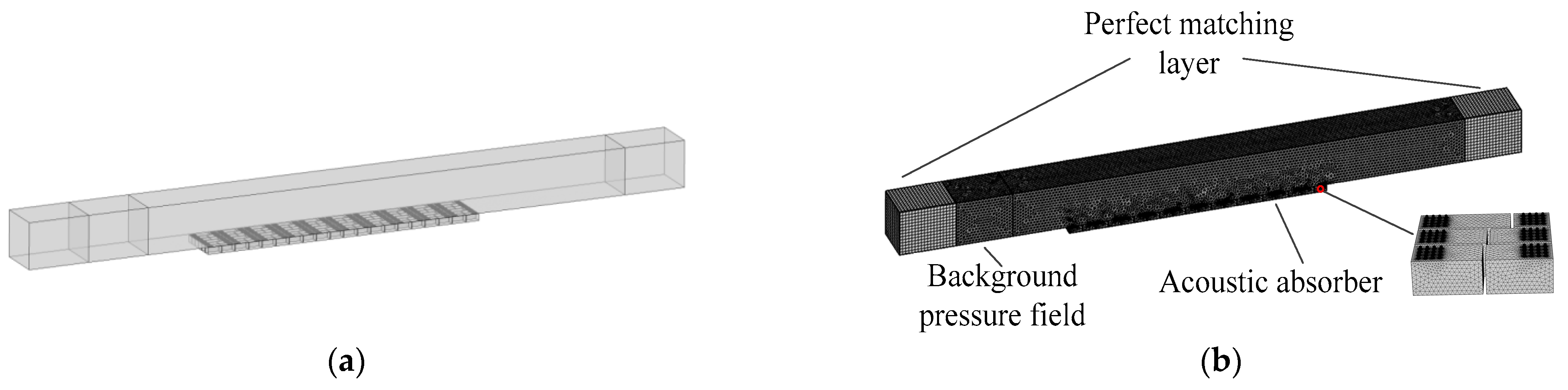

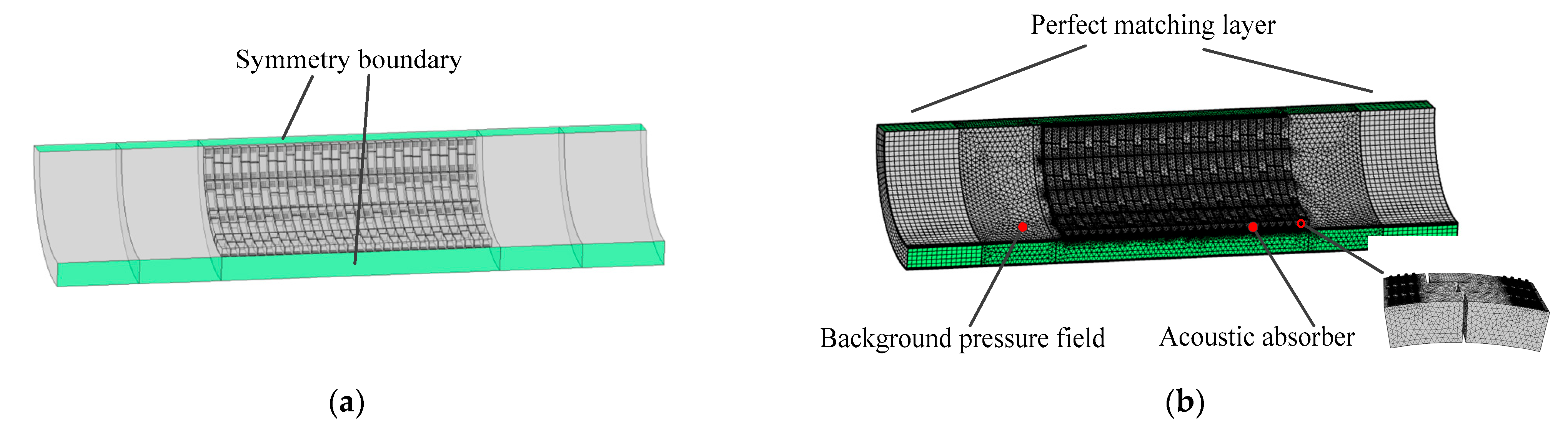

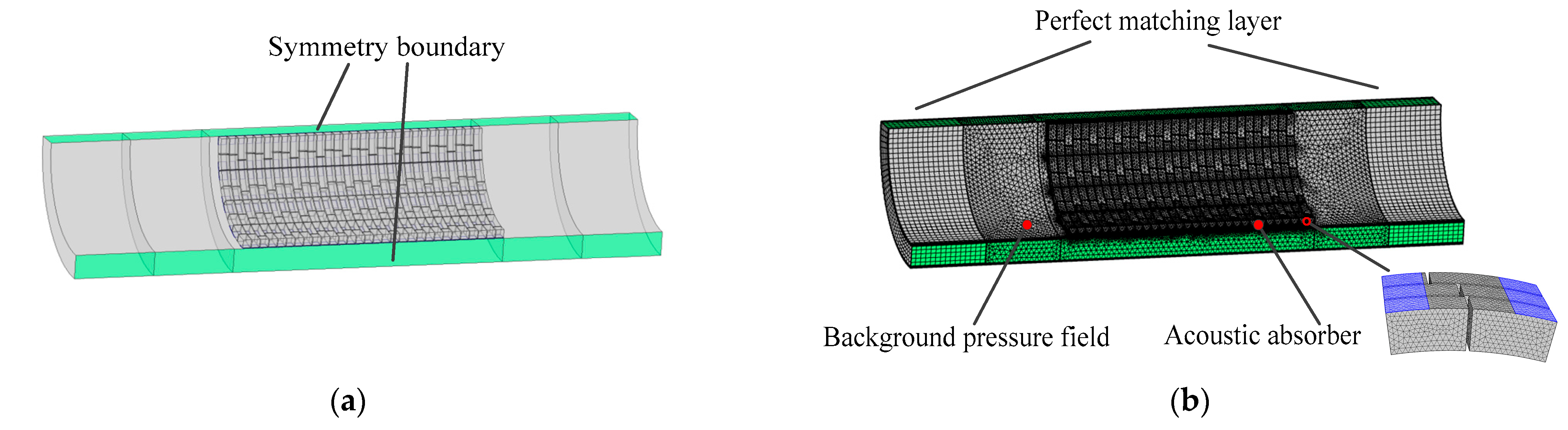

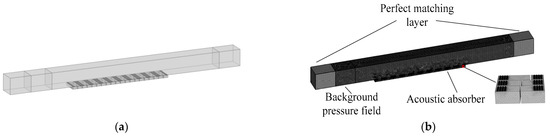

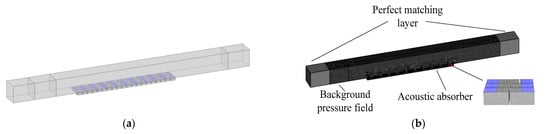

Referring to Figure 1, the designed planar non-uniform acoustic absorber was placed in the rectangular duct as an acoustically treated liner. In simulations, the length and width of the duct section were , the total length of the duct was and the length of the planar acoustic absorber was . The incident acoustic pressure level was taken as 120 dB. Again, for comparison purposes, both the FNSE and the IBNSE methods were used in simulations. Figure 16 and Figure 17 show the geometric and FE models of the rectangular duct–planar acoustic absorber (RDPAA) system suitable for the FNSE method and IBNSE method, respectively.

Figure 16.

Geometric and detailed FE models of the RDPAA system with grazing flow (suitable for the FNSE method). (a) Geometric model and (b) FE model.

Figure 17.

Geometric and detailed FE models of the RDPAA system with grazing flow (suitable for the IBNSE method). (a) Geometric model and (b) FE model.

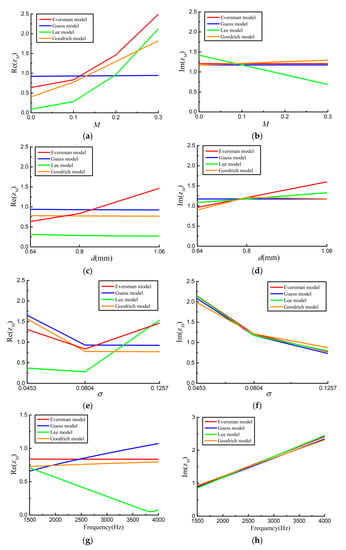

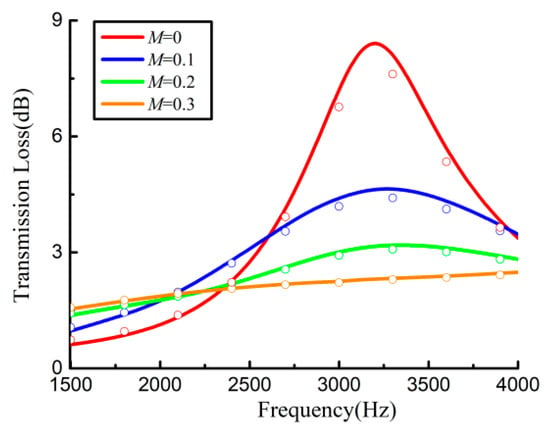

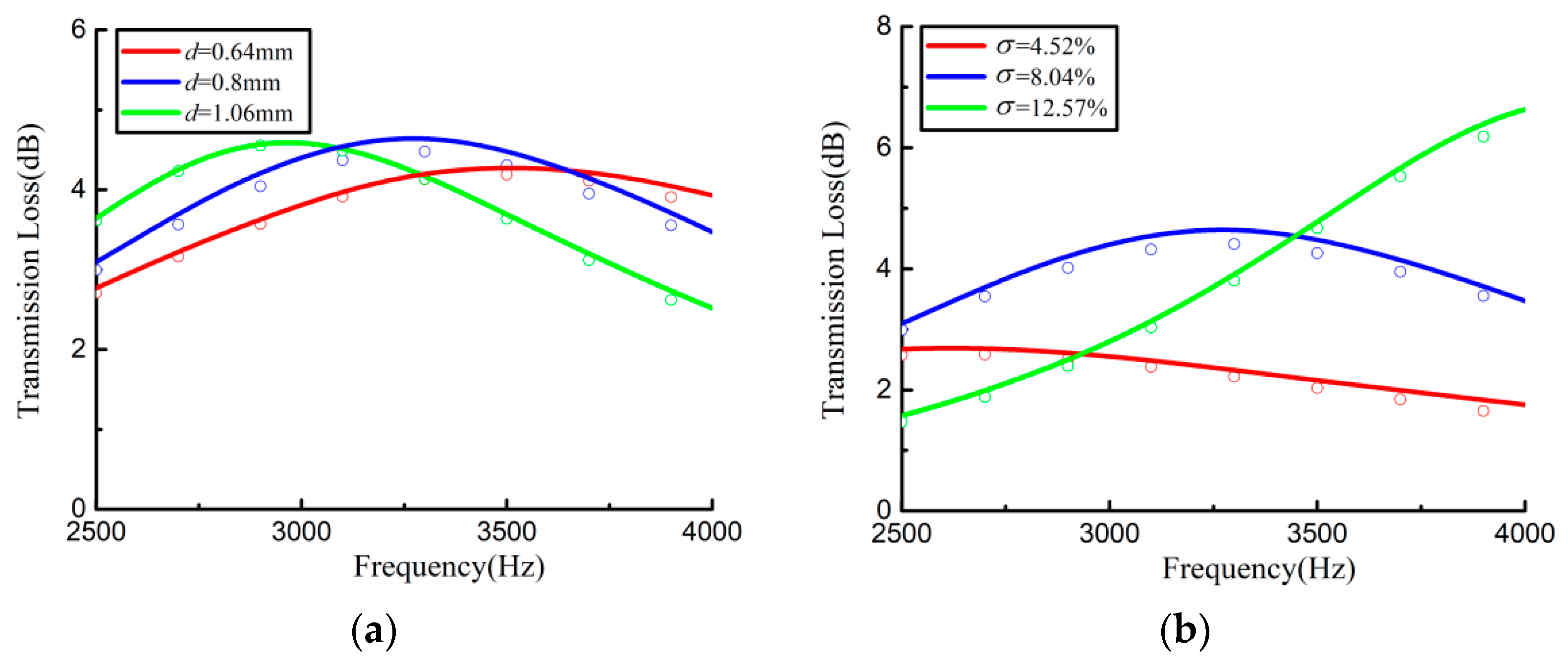

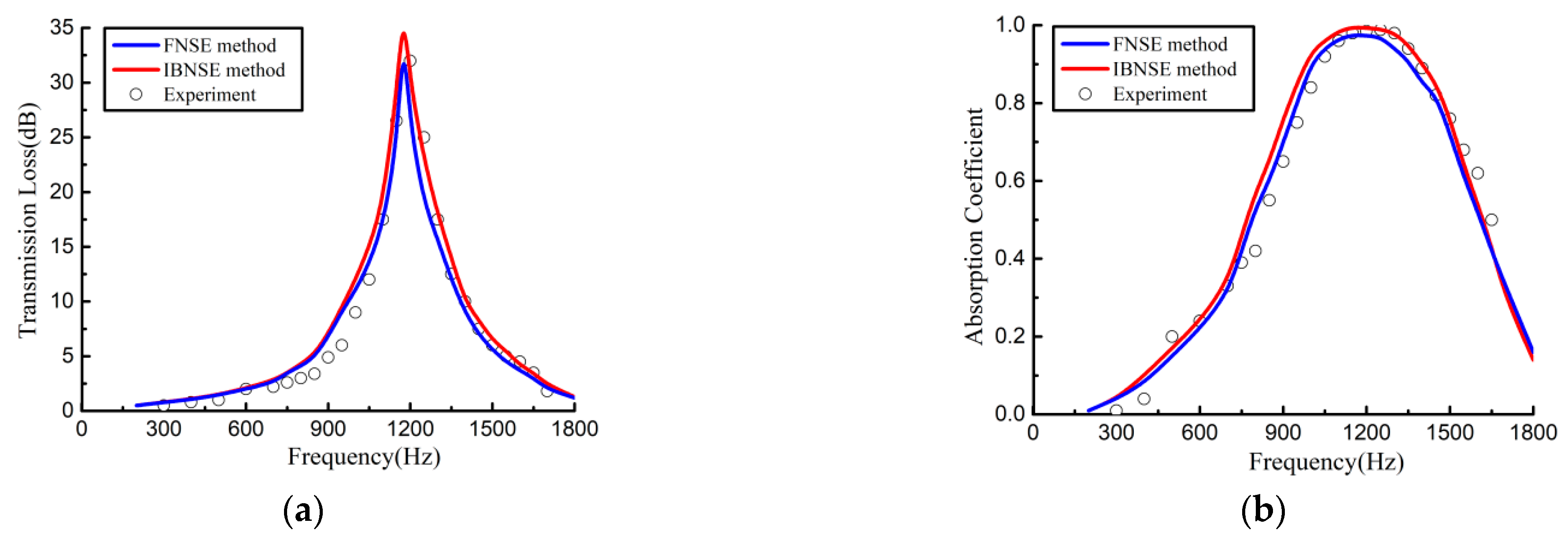

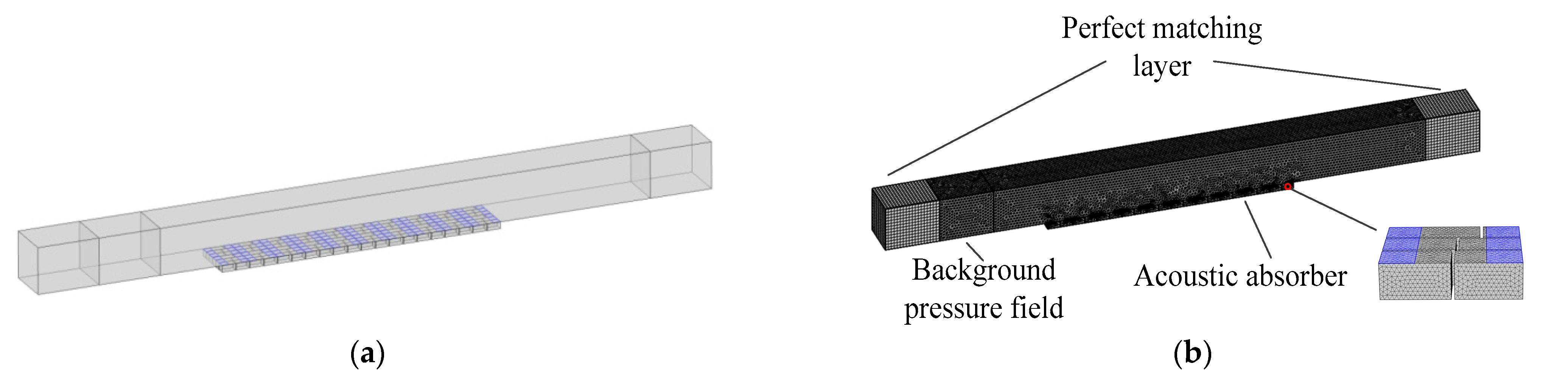

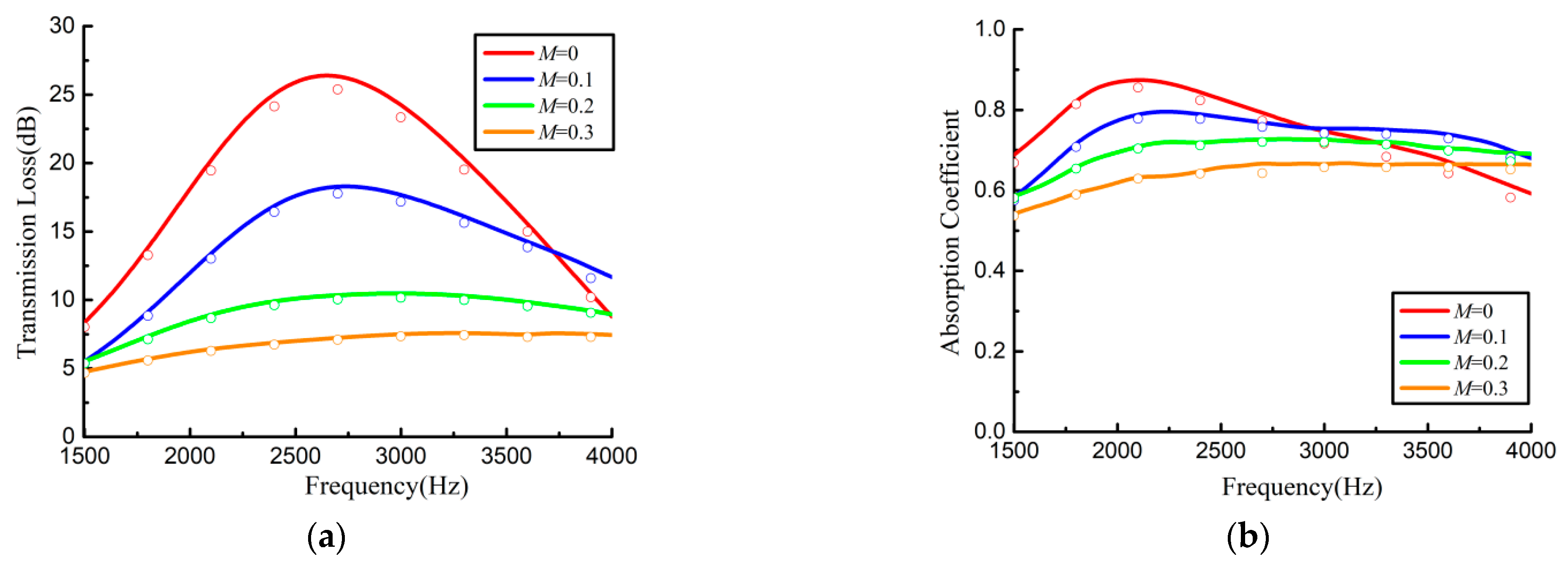

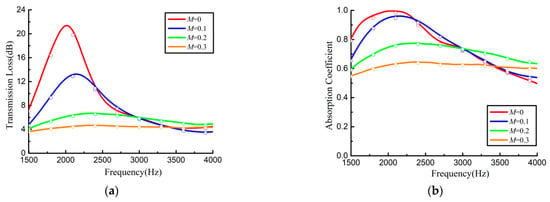

Figure 18 reveals that under different Mach numbers, the transmission loss and absorption coefficient obtained by the IBNSE method agreed very well with those obtained by the FNSE method, which once again proves the correctness of the IBNSE method. The FNSE method consumed 10 h and 20 min per calculation (corresponding to one Mach number), while the IBNSE method consumed only 3 h and 5 min per calculation, which demonstrates that the developed IBNSE method is computationally more efficient. It was observed that with the increase of incidence frequency, the transmission loss and acoustic absorption coefficient first increased and then decreased. The reason for this phenomenon can be explained by Figure 2h. As the frequency increases, the imaginary part of impedance of the perforated plate increases, which makes the imaginary part of the overall impedance change from negative to positive, with the point at which the imaginary part of the impedance is zero corresponds to the absorption peak. In addition, with the increase of Mach number, the peak values of transmission loss and absorption coefficient decreased, which led to a more uniform absorption performance within the considered frequency range. The reason is that an increase of Mach number leads to an increase in acoustic resistance and a decrease in acoustic reactance. The increased acoustic resistance usually results in a decreased peak value and increased bandwidth, while the decreased acoustic reactance shifts the absorption peak to a higher frequency.

Figure 18.

Comparisons of transmission loss and absorption coefficient of the RDPAA system under different grazing flow Mach numbers. The solid lines represent the results computed by the IBNSE method with Goodrich model, while the circles represent the results computed by the FNSE method. (a) Transmission loss and (b) acoustic absorption coefficient.

4.2. Annular Duct Acoustic Absorber

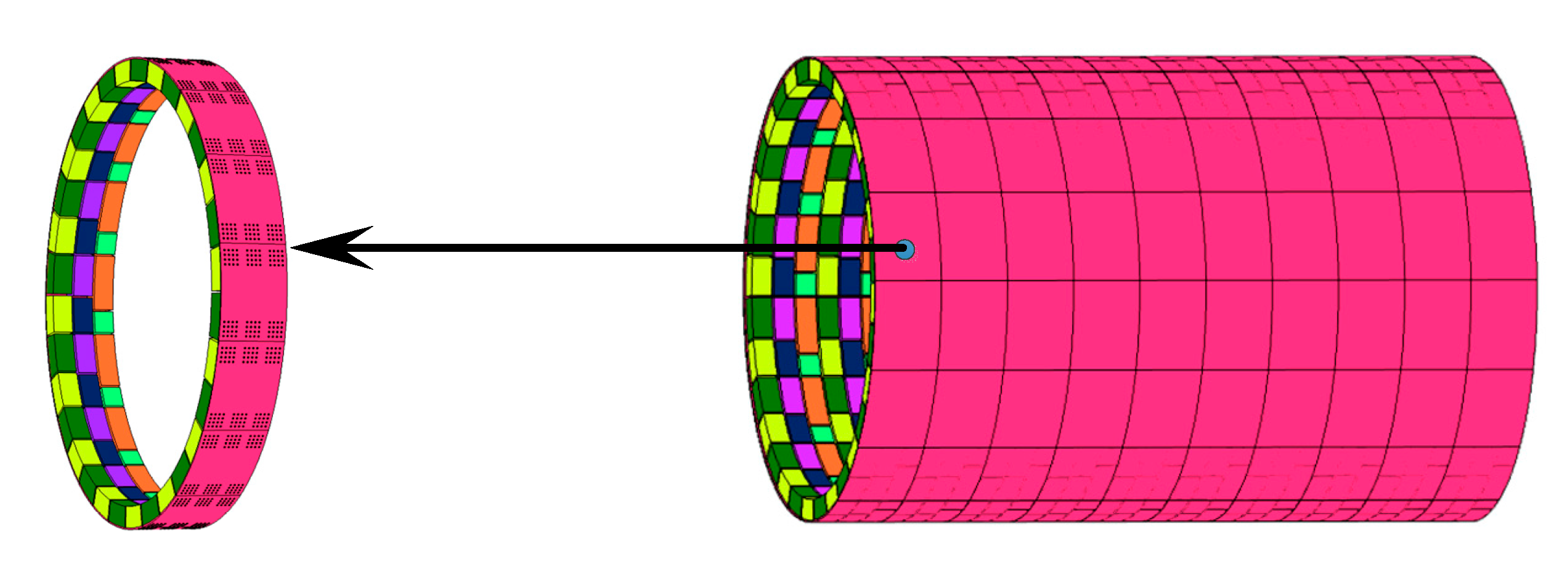

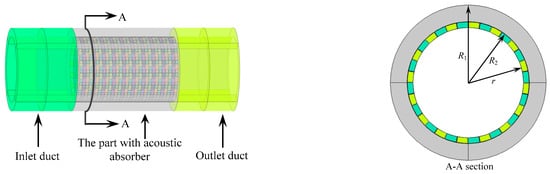

In addition to the rectangular duct, the planar BAU can be modified and applied to the annular duct structure. In Figure 19, the absorber with a circumferentially bent BAU is placed on the inner wall of the annular duct to form an annular duct–cylindrical acoustic absorber (ADCAA) system. In Figure 19, the outer and the inner radii of the duct are and , respectively. The inner radius of the acoustic absorber is and the outer radius is equal to . The total length of the duct is and the total length of the cylindrical acoustic absorber is .

Figure 19.

The ADCAA system.

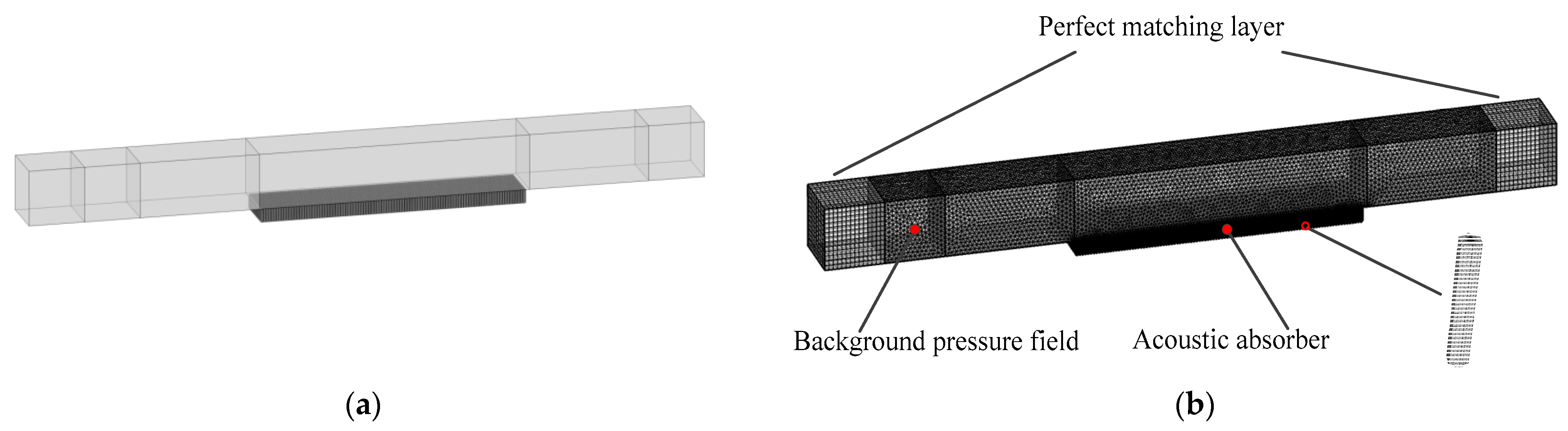

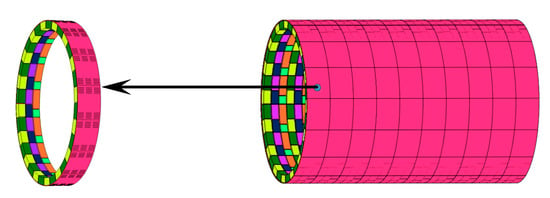

In order to adapt the planar BAU to the cylindrical surface, the perforated plate and the cavities in the planar BAU were bent along the circumference of the duct, while the volume of each cavity was kept unchanged, as shown in Figure 20. The bent BAU structure constitutes the basic acoustic absorption unit of the cylindrical non-uniform acoustic absorber. In Figure 20, the inner radius , the central angle of the bended BAU was and the axial length was . The central angles corresponding to the six cavities were , , , , and . The other parameter values were consistent with the original planar BAU structure.

Figure 20.

The bent BAU as the basic building block of the cylindrical non-uniform acoustic absorber.

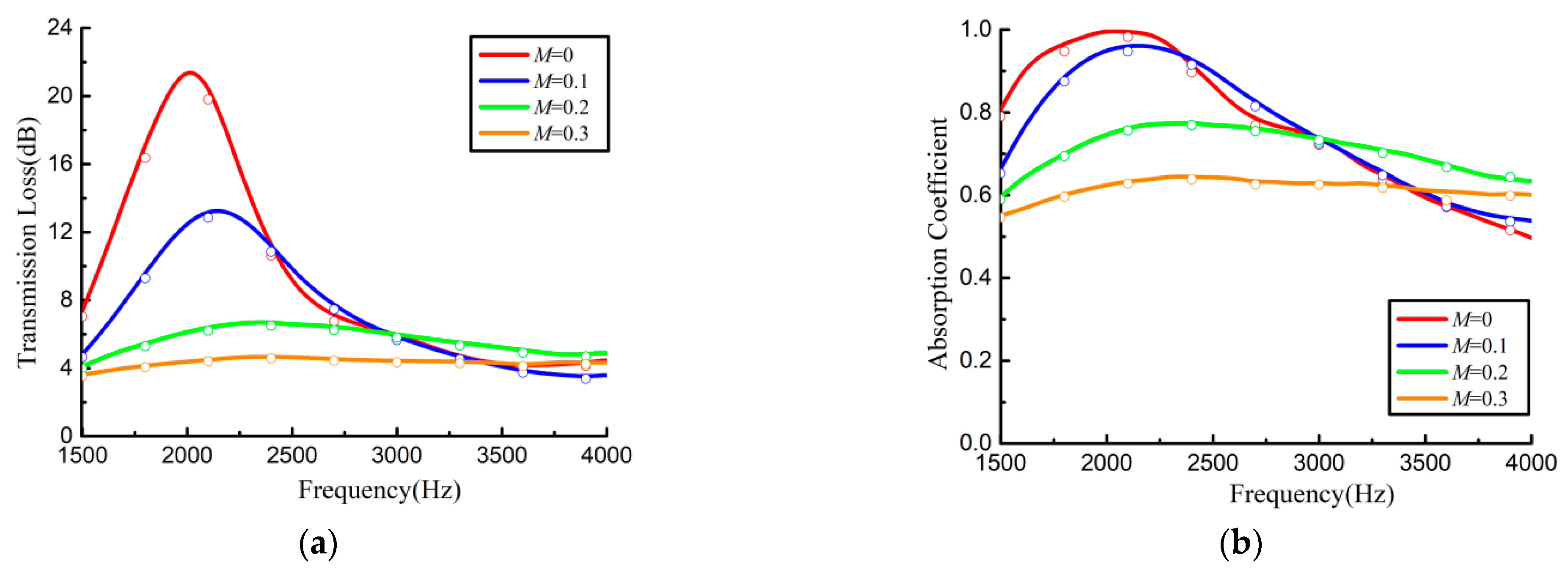

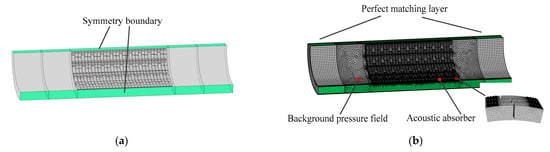

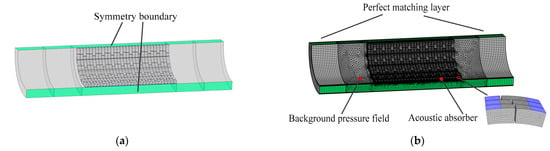

The final cylindrical acoustic absorber was constructed by arranging 16 and 10 bent BAUs along the circumferential and axial directions, respectively, as shown in Figure 21. Then, the cylindrical absorber was placed in the inner wall of the annular duct to form an ADCAA system. The FE models that are suitable for the FNSE method and the IBNSE method are shown in Figure 22 and Figure 23, respectively, in which only 1/4 of the cylindrical structure with symmetric boundary conditions was modeled.

Figure 21.

The cylindrical non-uniform acoustic absorber formed by the bent BAUs.

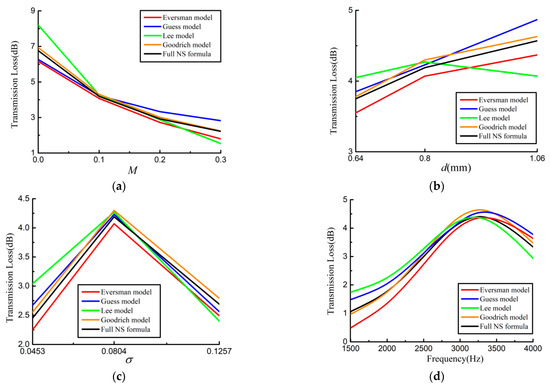

Figure 22.

The geometric and detailed FE models of the ADCAA system with grazing flow (suitable for the FNSE method). (a) Geometric model and (b) FE model.

Figure 23.

The geometric and detailed FE models of the ADCAA system with grazing flow (suitable for the IBNSE method). (a) Geometric model and (b) FE model.

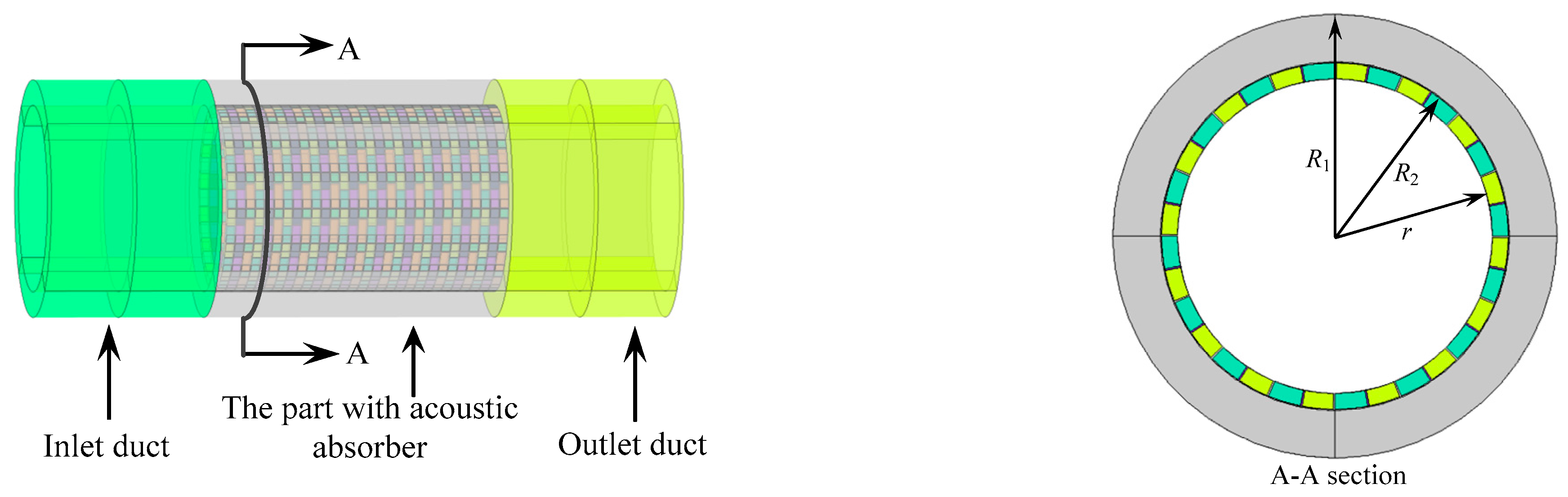

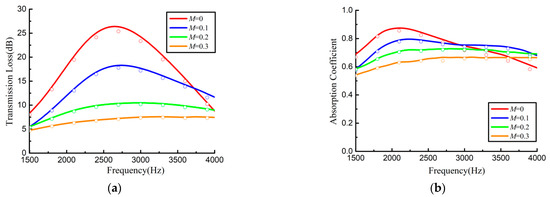

It can be seen form Figure 24 that under different Mach numbers, the transmission loss and absorption coefficient obtained by the IBNSE method also agreed very well with those obtained by the FNSE computations. The designed cylindrical acoustic absorber had good absorption performance over a very wide frequency range (absorption coefficient was higher than 50%). The absorption characteristics of the ADCAA system were similar to those of the RDPAA structure. However, the influence of Mach number on the absorption coefficient of the ADCAA system was smaller than that of the RDPAA system, which resulted in relatively flat absorption curves for different Mach numbers. This reveals that compared with RDPAA system, the absorption performance of the ADCAA system is not sensitive to the variations of Mach number. In this example, the FNSE method consumed 25 h and 40 min per calculation, while the IBNSE method consumed 8 h and 30 min per calculation, demonstrating that the calculation efficiency was greatly improved.

Figure 24.

Transmission loss and absorption coefficient of the ADCAA system under different grazing flow Mach numbers. The solid lines represent the results computed by the IBNSE method with Goodrich model, while the circles represent the results computed by the FNSE method. (a) transmission loss. (b) acoustic absorption coefficient.

In terms of the manufacturing of the absorber proposed in this paper, titanium alloy materials can be used for manufacturing if the application scenario involves high temperatures or high stress. If the above cases are not involved, ABS (acrylonitrile butadine styrene) materials can be used to save costs. The whole structure can be fabricated by 3D printing.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a broadband BAU absorber was first constructed by using an MPP and backed cavities with dissimilar lengths to produce peak absorption at multiple frequencies. Since each cavity length is extended along the MPP surface, different cavity volumes can be adopted to yield different resonance frequencies without increasing the thickness of the structure. The IBNSE method was developed to predict the attenuation characteristics of the duct acoustic system, in which comparisons of four semi-empirical impedance models were performed. It was found that the IBNSE method with Goodrich model was sufficient to accurately predict the acoustic attenuation of the absorber under the grazing flow condition. Using the BAU structure as the basic building block, planar and the cylindrical broadband non-uniform acoustic absorbers were constructed. The acoustic attenuation characteristics of the RDPAA and ADCAA systems under different grazing flow Mach numbers were calculated using the FNSE method as well as the developed IBNSE method. It was demonstrated that under different Mach numbers, these two acoustic systems exhibited good broadband absorption performances. The IBNSE method with Goodrich model was accurate and computationally efficient, and can be used to predict the absorption characteristics of acoustically treated ducts in the presence of grazing flow.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the study design, data acquisition, data analysis and data interpretation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maa, D.Y. Potential of microperforated panel absorber. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998, 104, 2861–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, Z.; Ma, F. Ultra-broadband acoustic absorption of a thin microperforated panel metamaterial with multi-order resonance. Compos. Struct. 2020, 246, 112366. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J.; Wen, J. Theoretical requirements and inverse design for broadband perfect absorption of low-frequency waterborne sound by ultrathin metasurface. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J. Low-frequency sound absorption of hybrid absorber based on micro-perforated panel and coiled-up channels. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 151901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, D. Low-frequency anechoic metasurface based on coiled channel of gradient cross-section. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 083501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Assouar, B. Acoustic metasurface-based perfect absorber with deep subwavelength thickness. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 063502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Udayakumar, A.K.; Mahendran, G.; Vasudevan, B.; Surve, J.; Parmar, J. Highly efficient, perfect, large angular and ultrawideband solar energy absorber for UV to MIR range. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaburro, G.; Parente, R.; Iannace, G.; Romero, V.P. Design Optimization of three-layered metamaterial acoustic absorbers based on PVC reused membrane and metal washers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liang, B.; Cheng, J.; Qiu, C. Twisted acoustics: Metasurface-enabled multiplexing and demultiplexing. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chang, H.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X. Single-channel labyrinthine metasurfaces as perfect sound absorbers with tunable bandwidth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 083503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Cheng, Q.; Cui, T.; Jing, Y. Acoustic planar surface retroreflector. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 065201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liang, B.; Zhang, L. Metascreen-based acoustic passive phased array. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2015, 4, 024003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Lu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Cui, F. Vibroacoustic modeling of an acoustic resonator tuned by dielectric elastomer membrane with voltage control. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 387, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, R.; Alù, A. Extraordinary sound transmission through density-near-zero ultranarrow channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 055501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, L. Acoustic silencing in a flow duct with micro-perforated panel liners. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 167, 107382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevon, E. Measurement methods and devices applied to A380 nacelle double degree-of-freedom acoustic liner development. In Proceedings of the 10th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Manchester, UK, 10–12 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Mao, X. Design of Honeycomb Microperforated Structure with Adjustable Sound Absorption Performance. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 6613701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Celik, A.; Meek, H.; Azarpeyvand, M. Double degree of freedom Helmholtz resonator based acoustic liners. AIAA AVIATION 2021 FORUM 2021. Available online: https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/abs/10.2514/6.2021-2205 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Watson, W. An acoustic evaluation of circumferentially segmented duct liners. AIAA J. 1984, 22, 1229–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.C.; Jones, M.G. Evaluation of variable facesheet liner configurations for broadband noise reduction. AIAA AVIATION 2020 FORUM 2020. Available online: https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/abs/10.2514/6.2020-2616 (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Palani, S.; Murray, P.; McAlpine, A.; Richter, C. Optimisation of slanted septum core and multiple folded cavity acoustic liners for aero-engines. AIAA AVIATION 2021 FORUM 2021. Available online: https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/6.2021-2172 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- McAlpine, A.; Astley, A.; Hii, V.J.T.; Baker, N.J.; Kempton, A.J. Acoustic scattering by an axially-segmented turbofan inlet duct liner at supersonic fan speeds. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 294, 780–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, N.H.; Jones, M.G.; Howerton, B.M.; Nark, D.M. Initial developments of a low drag variable depth acoustic liner. In Proceedings of the 25th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 20–23 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, A.; Wright, M.C.M. Acoustic scattering by a spliced turbofan inlet duct liner at supersonic fan speeds. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 292, 911–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.P.; Pagneux, V.; Lafarge, D.; Aurégan, Y. Modelling of sound propagation in a non-uniform lined duct using a multi-modal propagation method. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 289, 1091–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, T.R.; Dowling, A.P. Reduction of aeroengine tonal noise using scattering from a multi-segmented liner. In Proceedings of the 14th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–7 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, W.P.; Pagneux, V.; Lafarge, D.; Aurégan, Y. An improved multimodal method for sound propagation in nonuniform lined ducts. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 122, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Sun, X. Calculation model for sound propagation in duct with circumferentially non-uniform liner. In Proceedings of the 23rd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 5–7 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Namba, M.; Fukushige, K. Application of the equivalent surface source method to the acoustics of duct systems with non-uniform wall impedance. J. Sound Vib. 1980, 73, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.C.M. Hybrid analytical/numerical method for mode scattering in azimuthally non-uniform ducts. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 292, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, N.H.; Jones, M.G.; Bertolucci, B. Experimental evaluation of acoustic engine liner models developed with COMSOL Multiphysics. In Proceedings of the 23rd AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 5–7 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, J.; Mendoza, J.M.; Reimann, C.A.; Homma, K.; Alonso, J.S. High fidelity modeling tools for engine liner design and screening of advanced concepts. Int. J. Aeroacoustics 2021, 20, 530–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofano, A.; Murray, P.B.; Ferrante, P. Back-calculation of liner impedance using duct insertion loss measurements and fem predictions. In Proceedings of the 13th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Rome, Italy, 21–23 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Bodony, D.J. Numerical simulation of two-dimensional acoustic liners with high-speed grazing flow. AIAA J. 2011, 49, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhao, D. Lattice Boltzmann investigation of acoustic damping mechanism and performance of an in-duct circular orifice. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 135, 3243–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, D.; Hazir, A.; Mann, A. Turbofan broadband noise prediction using the lattice boltzmann method. AIAA J. 2018, 56, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassé, J.; Mendez, S.; Nicoud, F. Large-eddy simulation of the acoustic response of a perforated plate. In Proceedings of the 14th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–7 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.J.H.; Shaposhnikov, K.; Svensson, E. Using the linearized navier-stokes equations to model acoustic liners. In Proceedings of the 2018 AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; He, W.; Xin, F.; Lu, T. Nonlinear sound absorption of ultralight hybrid-cored sandwich panels. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 135, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversman, W.; Drouin, M.; Locke, J.; McCartney, J. Impedance models for single and two degree of freedom linings and correlation with grazing flow duct testing. Int. J. Aeroacoustics 2021, 20, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.W. Calculation of perforated plate liner parameters from specified acoustic resistance and reactance. J. Sound Vib. 1975, 40, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ih, J.G. Empirical model of the acoustic impedance of a circular orifice in grazing mean flow. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003, 114, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ruiz, M.; Kwan, H.W. Validation of Goodrich perforate liner impedance model using NASA Langley test data. In Proceedings of the 14th AIAA/CEAS aeroacoustics conference (29th AIAA aeroacoustics conference), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–7 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Cheng, L.; You, X. Hybrid silencers with micro-perforated panels and internal partitions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 137, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamet, E.; Selamet, A.; Iqbal, A.; Kim, H. Effect of flow on Helmholtz resonator acoustics: A three-dimensional computational study vs. Experiments. SAE Tech. Pap. 2011. Available online: https://www.sae.org/publications/technical-papers/content/2011-01-1521/ (accessed on 17 May 2011).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).